Exploring the Neural Correlates of Cognitive Reappraisal in Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Using Task-based Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging

In This Article

Summary

We introduce a protocol for exploring the neural correlates of a cognitive emotion regulation task, namely cognitive reappraisal, using functional magnetic resonance imaging. This protocol was used in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and healthy controls but can also be used in other clinical samples.

Abstract

Patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) show heightened brain activity in limbic and orbitofrontal regions when confronted with negative emotions, which could be associated with impairments in emotion regulation skills. The ability to regulate emotions is a necessary coping mechanism when facing emotionally distressing situations, and deliberate emotion regulation strategies such as cognitive reappraisal have been extensively studied in the general population. Despite this, little is known about potential deliberate emotion regulation deficits in OCD patients and the associated neural correlates. Here, we describe a protocol to investigate the neural correlates of deliberate emotion regulation (cognitive reappraisal) using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in OCD patients in comparison to a matched control sample. This protocol follows current gold standards for neuroimaging studies and includes both task activation and connectivity analysis (as well as behavioral data) to allow a more complete investigation. Therefore, we expect it will contribute to expanding the knowledge of the neural correlates of emotion (dys)regulation in OCD, and it could also be applied to explore emotion regulation deficits in other psychiatric disorders.

Introduction

Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a powerful tool for understanding psychiatric disorders because it allows researchers to observe brain function with relatively high spatial resolution, offering insights into the neural mechanisms underlying these conditions1. By detecting changes in blood flow, fMRI can pinpoint regions of the brain that are more active during specific tasks or in response to particular stimuli, highlighting abnormalities in brain function associated with disorders like depression, anxiety, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder. Furthermore, fMRI can reveal functional connectivity patterns, showing how different parts of the brain communicate with each other, which is crucial for understanding the complex networks disrupted in psychiatric disorders2. This non-invasive technique not only helps in identifying the neural correlates of psychiatric symptoms but also aids in exploring the psychological processes that could be underlying both symptom profiles and the effectiveness of treatments3.

Emotion regulation is one such process, which involves initiating new emotional responses or altering ongoing ones through various regulatory processes. There are several types of emotion regulation strategies, including attentional deployment (distraction), cognitive reappraisal (reinterpreting the meaning and personal connection to a stimulus), and suppression of emotional experience or expression4,5. Regarding reappraisal, previous fMRI studies have found that it is related to activation in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), dorsomedial and lateral frontal cortices, as well as temporal and parietal regions6,7. These frontal and cingulate brain regions are part of the frontoparietal cognitive control network, which plays a role in effortful regulation. In the context of reappraisal, this network helps cognitively reframe the negatively affective meaning of a stimulus into more neutral terms8. This network, in turn, controls bottom-up ventral and limbic regions such as the amygdala, involved in automatically evaluating emotional stimuli9. Previous studies using dynamic causal modeling analysis have examined the relationship between these dorsal and ventral regions during emotion regulation tasks using fMRI. They found that while the inferior frontal gyrus (IFG) is closely connected with the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (PFC), the ventromedial PFC represents the main pathway through which prefrontal regions directly influence the amygdala10,11.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is a psychiatric disorder that affects 1-3% of the population, characterized by distressing and recurring thoughts, urges, or images (obsessions), followed by repetitive mental or physical behaviors (compulsions)12. When exposed to disorder-relevant stimuli, patients with OCD experience negative emotions such as fear, anxiety, disgust, or guilt13,14, along with increased activity in ventral frontal and limbic brain regions like the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), the rostral ACC, and the amygdala15. Moreover, previous studies have shown that patients with OCD have difficulties regarding emotion regulation, particularly when employing cognitive reappraisal strategies16. Thus, it is hypothesized that the augmented emotional reactivity found in OCD is linked to these emotion regulation impairments17,18,19. Indeed, cognitive-behavior therapy (a first-line treatment for OCD20) includes training patients in emotion regulation strategies to help them cognitively reappraise negative, symptom-triggering situations as non-threatening.

Neurobiologically, the dysfunctional interplay between ventral and dorsal networks is thought to be associated with altered emotional processing and regulation in various psychiatric disorders21,22,23. In OCD, both functional and structural neuroimaging studies have revealed impairments in brain areas linked to these networks24,25,26, with some functional deficits normalizing after symptom improvement27,28. This evidence supports the idea that the emotion regulation difficulties found in OCD could be related to impaired control functioning of dorsal brain regions and/or hyperactivation in the ventral system. Thus, restoring the balance between these networks through cognitive reappraisal training may potentially improve patients' symptoms29. Despite this evidence, there is a scarcity of previous literature exploring, through the use of fMRI, the neural correlates of cognitive emotion regulation in OCD. Thus, the definition of a standardized protocol that could be used by all research teams interested in this topic would allow the advancement of knowledge in this research area in a consistent and robust way.

Protocol

The current study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional Ethics Committee of Hospital de Braga and the University of Minho (Braga, Portugal). All procedures involved in this work adhere to the ethical standards of the relevant institutional and National Committees on Human Experimentation, as well as the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, revised in 2008.

1. Participants

NOTE: Adult (≥18 years old) patients with OCD were recruited from the Department of Psychiatry at Hospital de Braga (Braga, Portugal) during regular consultations.

- Recruit adult patients (≥18 years old) with OCD during regular consultations where they are diagnosed by an experienced psychiatrist based on standard criteria (see Table of Materials). Conduct the Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview30 to assess other potential psychopathological conditions.

- Regarding patients with OCD, set the exclusion criteria to include the current presence of other psychiatric diagnoses (Axis I or Axis II disorders) or current or past major neurological or medical conditions.

NOTE: Psychopharmacological medication use was not an exclusion criterion; most patients (80.64%) were on medication at the time of recruitment, with treatments remaining consistent throughout the study. - Recruit healthy controls (HC) from the same sociodemographic background, using convenience sampling through the mailing lists and social networks of the institution, as well as the community contacts from the researchers.

- Exclude HC if they have any current or past neurological, psychiatric, or major medical conditions, or if they have current or past treatment with psychopharmacological medication.

- Consider contraindications for performing an MRI (metallic implants or claustrophobia) to be a general exclusion criterion for all participants.

- Confirm the inclusion/exclusion criteria during the psychiatry consultation for the patients or by a telephone interview for the HC. If participants fulfill the inclusion criteria and agree to participate, schedule a date for participation in the study.

- The day of the study, before starting the study procedures, present and explain the written informed consent form to the participants and obtain their written informed consent before continuing.

2. Experimental protocol

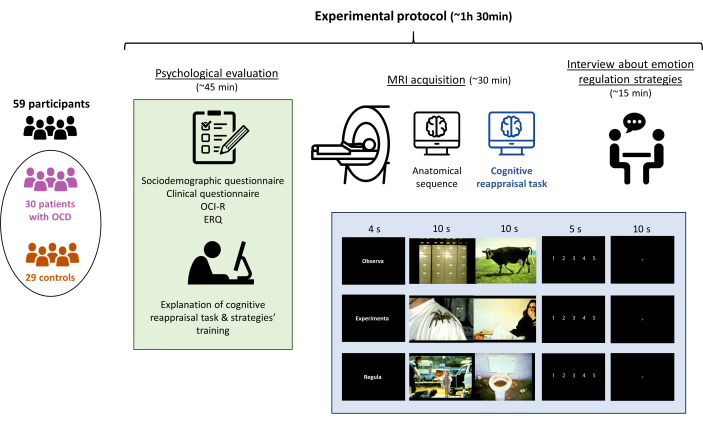

NOTE: Perform a psychological evaluation followed by an MRI acquisition, with the whole experimental protocol lasting no more than 1.5 h in total (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Experimental protocol of the study. The participants (30 patients with OCD and 29 matched controls) underwent a psychological evaluation, followed by the explanation of the cognitive reappraisal task, the MRI acquisition (including the performance of the task), and finally, an interview to confirm that the task was adequately performed. The whole protocol lasted approximately 90 min. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

- Psychometric assessment (~45 min)

- Complete the following psychometric scales, validated in the respective population, as well as sociodemographic and clinical questionnaires, in the following order:

- Sociodemographic questionnaire: Collect information on sex/gender, year of birth, years of education, residential area, civil status, family status, job status, and hand dominance. See Supplementary File 1 for the questionnaire used in this study, accompanied by a translation to English.

- Clinical questionnaire: Collect information on substance use (tobacco, alcohol, or other drugs), habitual pharmacological use, current physical or psychiatric disorder diagnosis, and history of psychiatric disorders. See Supplementary File 2 for the questionnaire used in this study, accompanied by a translation to English.

- Respond to the obsessive-compulsive inventory (OCI-R). See Supplementary File 3 for the questionnaire used in this study, accompanied by a translation to English.

NOTE: This is an 18 item inventory applicable to both patients with OCD and HC and measures six groups of symptoms: washing, checking, ordering, hoarding, obsessing, and neutralizing31,32. The scoring for the washing subscale is obtained by adding the scores of items 5, 11, and 17; for checking items 2, 8, and 14; for ordering items 3, 9, and 15; for hoarding items 1, 7, and 13; for obsessing items 6, 12, and 18; and for neutralizing items 4, 10, and 16. A total score can also be obtained by adding the scores of all subscales. - Apply the emotion regulation questionnaire (ERQ), which assesses the habitual use of two emotion regulation strategies: reappraisal and suppression33,34. Calculate the scores on the reappraisal subscale by adding the scores of items 1, 3, 5, 7, 8, and 10, and on the suppression subscale by adding the scores of items 2, 4, 6, and 9. See Supplementary File 4 for the questionnaire used in this study, accompanied by a translation to English.

- To measure the severity of obsession and compulsive symptoms, ensure that patients with OCD have completed the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (Y-BOCS) during the psychiatry consultation when they are recruited35,36. Otherwise, collect this information during the psychometric assessment. See Supplementary File 5 for the questionnaire used in this study, accompanied by a translation to English.

- After completing the scales, explain the cognitive reappraisal task to be performed at the scanner, and train the participants in the emotion regulation strategies to be used (see section 2.3).

NOTE: It is important to try to always apply these scales before the MRI acquisition to make sure that the cognitive reappraisal task does not impact the scales' responses.

- Complete the following psychometric scales, validated in the respective population, as well as sociodemographic and clinical questionnaires, in the following order:

- Imaging data acquisition (~30 min)

- Acquire imaging data on a 3T scanner (see Table of Materials), equipped with a 32 channel head coil. Before starting with the MRI acquisition, instruct participants to lie supine on the scanning bed, and add additional cushioning for the head to make sure participants are comfortable during the scan, which will minimize movement. Provide participants with ear protection, a response box in their right hand (see section 2.3), and an emergency stop button in their left hand in case they have an urgent need to stop the scanner.

- Have all participants perform a cognitive reappraisal task inside the scanner (see below). During this task, acquire a multi-band echo-planar imaging (EPI) sequence, (CMRREPI 2D) sensitive to fluctuations in the Blood Oxygenation Dependent Level (BOLD) contrast, with the following parameters (7.8 min): repetition time (TR) = 1,000 ms, echo time (TE) = 27 ms, flip angle (FA) = 62°, 2 mm3 isometric voxel size, 64 axial slices over a matrix of 200 x 200 mm2.

- Include in the scanning session an anatomical gradient echo Magnetization-Prepared rapid acquisition in the sagittal plane for registration purposes (MPRAGE, TR = 2,420 ms, TE = 4.12 ms, FA = 9°, field of view (FOV) = 176 x 256 x 256 mm3, 1 mm3 isometric voxel size).

NOTE: Before starting data collection, make sure that the participants can see the stimulus presentation clearly in the screen projection and that the response buttons are appropriately collecting the responses. Ensure that the participants are seeing the stimuli in the correct orientation and not flipped or reversed.

- fMRI cognitive reappraisal task

- Before scanning, train the participants in distancing and reinterpretation strategies. For example, while showing pictures with disturbing scenarios (see Supplementary File 6 for the ones used in this study), instruct them to reappraise their emotions by cognitively reframing the scene in one of the following ways: (i) the situation is not as bad as it first appears (i.e., interpreting the situation in a more positive light) (reinterpretation); (ii) the situation will get better with time (reinterpretation); (iii) the depicted scene is not real (e.g., if there are people on the scene, thinking that they are actors) (distancing); and (iv) the people shown in the scene are strangers, and thus it will not affect oneself (distancing). Specifically instruct the participants not to use non-cognitive strategies (such as looking away) during the task.

- Use the cognitive reappraisal task37 while acquiring the fMRI sequence. The task consists of a series of blocks, including neutral or negative picture stimuli, that participants are asked to:

- Observe (to passively observe neutral stimuli).

- Maintain (to actively focus on the emotions provoked by the negative stimuli, maintaining them over time).

- Regulate (to reappraise the emotions induced by the negative stimuli using the cognitive reappraisal strategies previously trained).

- Use the following 24 stimuli (photographs) from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS38):

- Present eight neutral pictures (e.g. household objects) in the Observe condition (codes 1670, 5395, 5455, 5660, 5900, 6150, 7000, 7496, see Supplementary File 7).

- Use 16 highly unpleasant, arousing pictures (e.g., mutilations) in the Maintain (codes 2661, 3230, 3300, 6360, 6831, 9041, 9560, 9570, see Supplementary File 8) and Regulate (codes 2141, 3030, 6838, 7380, 9300, 9530, 9561, 9582, see Supplementary File 9) conditions.

- Structure the task to consist of 12 blocks, four blocks for each condition (Observe, Maintain, or Regulate). Pseudorandomize instructions throughout the task to avoid inducing a sustained mood state.

NOTE: For this experiment, the condition order was Regulate, Maintain, Observe, Maintain, Regulate, Observe, Maintain, Observe, Regulate, Observe, Maintain, Regulate. - Begin each block with the instruction (Observe, Maintain, or Regulate) presented for 4 s in the middle of the screen. After the prompt, show participants two different stimuli of equivalent valence for 10 s each. After presenting the second stimulus of each block, have participants self-rate the intensity of the negative emotion experienced on a 1-5 number scale (where 1 represents feeling 'neutral' and 5 'extremely negative'). To minimize carryover effects, show a fixation cross in the middle of the screen for 10 s after each block.

NOTE: Stimuli were selected based on their normative scores for emotional arousal and valence. Balancing the emotional content of negative pictures across Maintain and Regulate conditions should be carefully considered to avoid confounding effects due to differences in these properties. - Use the referenced software39 (see Table of Materials) and an MRI-compatible angled mirror system to display the instructions of the task and the visual stimuli.

- Use an MRI-compatible response pad (see Table of Materials) to record in-scanner emotional ratings.

- After the MRI session, interview the participants to make sure that they followed the instructions and adequately performed the task. Ask them the type of emotion regulation strategies that were used (reinterpretation, distancing, or others), and whether they changed strategies during the task or if there was a specific strategy that worked best for them and was kept constant throughout the task. See Supplementary File 10 for the questionnaire used in this study, accompanied by a translation to English.

- Use the information from the post-MRI interview to categorize the sample in different subgroups depending on the emotion regulation strategy used (distancing, reinterpretation, or both), and further explore subsequent analyses separately for each of these subgroups.

3. Data analysis

- Behavioral analysis

- Use the referenced software (see the Table of Materials) for conducting the statistical analyses.

- Consider P values < 0.05 statistically significant.

- Check the normality of continuous variables using the Shapiro-Wilk's test of normality, and depending on the results, compare groups on these variables using independent-sample t-tests or Mann-Whitney's U tests.

- Use a chi-squared test to compare the sex/gender distribution between groups.

- Use a chi-squared test to compare the emotion regulation strategy distribution between groups.

- Use a 2 x 3 repeated-measures ANOVA to analyze potential differences in each condition's (Observe, Maintain, and Regulate) in-scanner ratings between both groups. Then, use post-hoc tests to check for differences between every two conditions, including Holm's correction for multiple comparisons. Do this for the full sample as well as for each emotion regulation subgroup.

- Calculate the participants' success in decreasing their in-scanner negative emotion experience by subtracting the mean Regulate ratings from the mean Maintain ratings (Success = Maintain - Regulate), and compute participants' emotional reactivity during emotional processing by subtracting the mean Observe ratings from the mean Maintain ratings (Reactivity = Maintain - Observe). Then, compare the groups on the computed variables using independent-sample t-tests or Mann-Whitney tests depending on the normality of the data. Do this for the full sample as well as for each emotion regulation subgroup.

NOTE: Several print screens showing how to perform these analyses on JASP can be found in Supplementary File 11.

- Preprocessing of neuroimaging data

NOTE: Preprocess images using the referenced software40,41 (see the Table of Materials). This software performs a standardized robust preprocessing pipeline for both functional and structural data and adapts its pipeline depending on what data and metadata are available and are used as the input, without the need of defining any parameters or steps by the user. For more details of the pipeline, see Supplementary File 11 and the workflows section in the documentation.- Use an exclusion criterion of mean framewise displacement (FD) > 0.5 mm to account for in-scanner movements, looking at the mean FD values included on the quality-check report generated by the preprocessing software.

NOTE: There were no participants exceeding this threshold for this study; thus, no participants had to be excluded because of this. - Additionally, visually inspect the output reports to assess the accuracy of the coregistration and identify any other potential issues during the preprocessing pipeline.

- Use the fslmaths function from the referenced software42 (see the Table of Materials) to spatially smooth the resulting time series with a full-width-at-half-maximum (FWHM) kernel of 8 mm (see Supplementary File 11 for the specific command used in this study).

- Use an exclusion criterion of mean framewise displacement (FD) > 0.5 mm to account for in-scanner movements, looking at the mean FD values included on the quality-check report generated by the preprocessing software.

- fMRI task activation analysis

NOTE: Perform task activation analysis using the referenced software (see the Table of Materials).- As a preliminary step, adjust the matrix dimensions of the fMRI time-series data resulting from preprocessing to allow compatibility between software using the 3dresample function from the referenced software43 (see the Table of Materials), with the "MNI152_T1_2mm_brain.nii.gz" template as a master image (see Supplementary File 11 for the specific command used in this study).

- For the first-level (single-subject) analyses, define the following contrasts of interest in SPM12: Maintain > Observe, which allows detection of activations associated with the experienced negative emotions, and Regulate > Maintain, in order to identify activations related to the implementation of cognitive reappraisal strategies.

- Model conditions for the 20 s that the images were on the screen, excluding instruction, rating, and cross-fixation periods. Convolve the BOLD response at each voxel with the canonical hemodynamic response function and use a 128 s high-pass filter.

- Use the mean cerebrospinal fluid and white matter signals as covariates, as well as variables to correct for movement, calculated during fMRIprep preprocessing. The movement variables included the first six aCompCor components, in addition to FD and DVARS (Derivative of root mean square VARiance over voxelS).

- For the second-level (group) analyses, use two-sample t-tests in order to look for differences between groups in the contrasts of interest. Do this for the full sample as well as for each emotion regulation subgroup. Analyze the data at the whole-brain level, using cluster thresholding correction: voxel p < 0.001 uncorrected, and cluster p < 0.05 family-wise error (FWE) corrected.

NOTE: Several print screens of the process for performing this analysis can be found in Supplementary File 11.

- Psychophysiological interaction analysis

- To explore the connectivity between brain regions stimulated by the different task conditions, perform a psychophysiological interactions (PPI) analysis in the referenced software.

- To perform this analysis, select one or several seed regions based on at least two different approaches: a data-driven approach, selecting regions found to be significantly different between groups in the task-activation analysis; or a theory-driven approach, selecting seeds based on previous literature. For this study, choose the PPI seeds based on previous literature on emotional processing alterations in patients with OCD.

- For example, use the following regions from Picó-Pérez et al.15 meta-analysis, identified as having hyperactivation during emotional processing in patients with OCD compared to HC: a cluster extending from the right anterior insula to the amygdala and putamen, the left angular gyrus, a cluster comprising the left amygdala and ventral putamen, the left precentral gyrus, the medial prefrontal cortex, and the left thalamus (see Table 1 for further information).

- Explore the influence of the contrasts of interest (the 'psychological' factor) on the strength of the time-course correlations between the six seeds selected and all the other regions of the brain (the 'physiological' factor).

- Estimate functional connectivity maps for each contrast and each seed by means of whole-brain linear regression analyses. Use a high-pass filter set at 128 s to remove low-frequency drifts of less than approximately 0.008 Hz. Generate contrast images for each subject (first-level analyses) by estimating the regression coefficient between the seed time series and each voxel's signal from the rest of the brain.

- To assess group differences (second-level analyses), include the resulting images from the previous step in a two-sample t-test analysis for each of the contrasts. Do this for the full sample as well as for each emotion regulation subgroup. Use the same significance thresholding as in the fMRI task activation analysis. Additionally, apply a Bonferroni correction to the p-value of these results to take into account the multiple comparison correction by the number of seeds explored (p < 0.05 / 6 = p < 0.0083).

NOTE: Several print screens of the process for performing this analysis can be found in Supplementary File 11.

Table 1: Seeds used in the psychophysiological interaction analysis. Abbreviations: Ke, cluster extent in voxels; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute. Please click here to download this Table.

Results

Table 2 includes a summary of the clinical and sociodemographic information of the participants. The study included 67 adult individuals (34 OCD patients and 31 HC). However, six participants (four patients and two controls) were excluded due to MRI artifacts or suboptimal task performance (when interviewed at the end, two participants reported that no regulation strategies were applied and that they were not paying attention). The final sample consisted of 30 patients with OCD (17 females; mean age = 28.97, SD = 11.14 years) and 29 HC (15 females; mean age = 29.35, SD = 12.14 years). Both groups were matched with respect to age, years of education, sex/gender distribution, and the emotion regulation strategy used during the task. Table 2 also presents clinical information for the group of patients with OCD, including symptom severity, age of onset, and medication status.

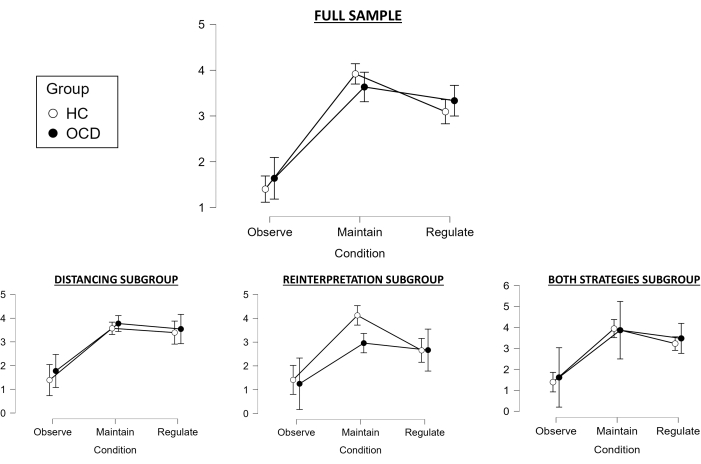

Regarding the ratings during the task for the full sample, the Huynh-Feldt test was used as our 2 x 3 repeated-measures ANOVA violated the assumption of sphericity. The main effect of condition was statistically significant (F(1.783, 98.067) = 112.728, p < .001), and post-hoc tests revealed that the Maintain condition significantly differed from the Observe condition (pointing towards successful negative emotion induction for both groups; t = −14.423, pholm < .001), and that the Regulate condition differed from Maintain (indicating also successful emotion regulation for both groups; t = 3.597, pholm < .001) (Figure 2). However, the main effect of group was not statistically significant (F(1, 55) = 0.155, p = .695), and there was also no significant interaction between groups and conditions (F (1.783, 98.067) = 1.877, p = .163). However, the Success variable significantly differed between groups (t(55) = 2.15, p = .036), with controls showing better regulation than patients with OCD.

When exploring this for the Distancing subgroup, the assumption of sphericity was also violated so the Huynh-Feldt test was used again as our 2 x 3 repeated-measures ANOVA. The main effect of condition was statistically significant (F(1.398, 27.961) = 35.704, p < 0.001), and post-hoc tests revealed that the Maintain condition significantly differed from the Observe condition (indicating successful negative emotion induction; t = −7.666, pholm < 0.001), but with the Regulate condition no longer significantly differing from Maintain (pointing towards a failure in successfully regulating emotions; t = 0.755, pholm < 0.455) (Figure 2). The main effect of group was also not significant (F(1, 20) = 0.887, p = 0.358), and the same regarding the interaction between group and condition (F (1.398, 27.961) = 0.103, p = 0.832). Accordingly, the Success variable was also not significantly different between groups (t(20) = -0.132, p = 0.896).

Regarding the Reinterpretation subgroup, a 2 x 3 repeated-measures ANOVA without sphericity correction was performed, since the assumption of sphericity was not violated. The main effect of condition was also significant (F(1.8, 23.404) = 28.355, p < 0.001), and post-hoc tests revealed that the Maintain condition significantly differed from the Observe condition (pointing towards successful negative emotion induction; t = −7.48, pholm < 0.001), and that the Regulate condition differed from Maintain (indicating successful emotion regulation; t = 2.983, pholm < 0.006) (Figure 2). However, the main effect of group was not statistically significant (F(1, 13) = 2.623, p = 0.129), and there was also no significant interaction between groups and conditions (F (1.8, 23.404) = 2.312, p = 0.126). However, the Success variable significantly differed between groups (t(13) = 2.664, p = 0.019), with controls showing better regulation than patients with OCD.

Finally, with regards to the Both strategies subgroup, a 2 x 3 repeated-measures ANOVA without sphericity correction was also performed, since the assumption of sphericity was not violated. The main effect of condition was statistically significant (F(1.592, 22.294) = 27.772, p < 0.001), and post-hoc tests revealed that the Maintain condition significantly differed from the Observe condition (indicating successful negative emotion induction; t = −7.114, pholm < 0.001), but with the Regulate condition no longer significantly differing from Maintain (pointing towards a failure in successfully regulating emotions; t = 1.634, pholm < 0.114) (Figure 2). The main effect of group was not statistically significant (F(1, 14) = 0.245, p = 0.629), and there was also no significant interaction between groups and conditions (F (1.592, 22.294) = 0.143, p = 0.867). Similarly, the Success variable was not significantly different between groups (t(13) = 0.597, p = 0.56).

Overall, when considering the full sample, negative emotion induction was successful, and emotion regulation was effective in both groups, although controls seemed to show better emotion regulation than patients with OCD when considering the success variable. Regarding the specific emotion regulation strategy subgroups, negative emotion induction was successful for all of them, while emotion regulation appeared to fail for the Distancing and Both strategies subgroups, being successful only for the Reinterpretation subgroup. Moreover, only this subgroup showed significant group differences in the success variable, with controls presenting better emotion regulation in comparison to patients with OCD (in line with the full sample). This provides evidence toward the benefits of employing reinterpretation strategies in this task both for ensuring successful emotion regulation in general and for detecting significant differences between control and patient groups. These findings should be taken with caution though, given the decreased sample size of each subgroup and the associated loss of statistical power when performing the subgroup analyses.

Regarding the psychometric scales, there were no significant between-group differences on the ERQ, but patients with OCD scored significantly higher than HC in all OCI-R subscales, with the exception of OCI-R Hoarding (Table 2).

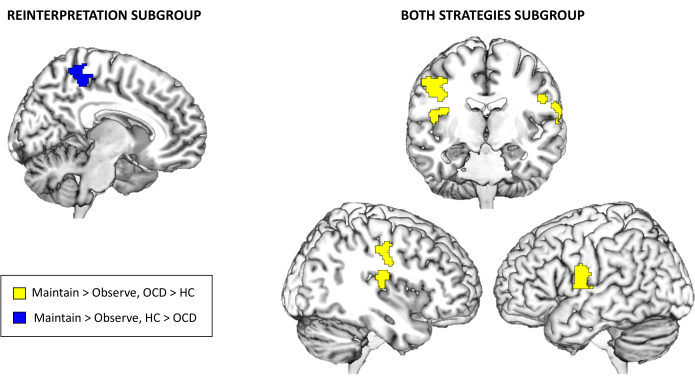

Finally, with regards to the fMRI task activation results, there were no significant between-group differences for the full sample at the whole-brain level for Maintain > Observe or Regulate > Maintain at the selected multiple comparison corrected threshold. However, when exploring the subgroups depending on the emotion regulation strategy used, significant between-group differences emerged for the Reinterpretation and Both strategies subgroups. Specifically, for the Reinterpretation subgroup, controls presented higher activation than patients with OCD in the precuneus for the Maintain > Observe contrast. On the other hand, for the Both strategies subgroup, patients with OCD presented increased activation in the right posterior insula and the bilateral precentral gyri also for the Maintain > Observe contrast (see Table 3 and Figure 3). There were no statistically significant findings for the Distancing subgroup or for the Regulate > Maintain contrast.

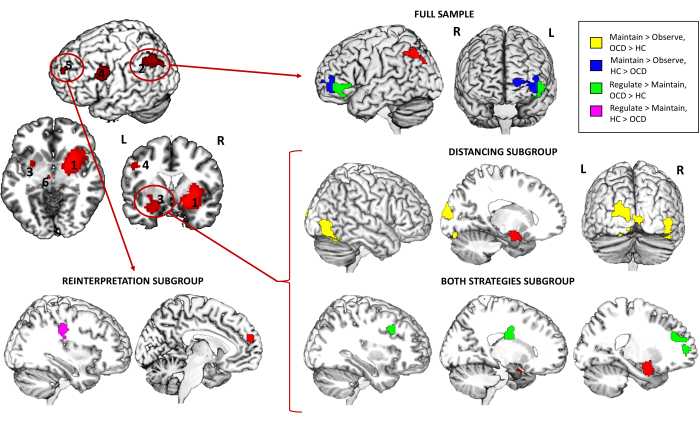

Furthermore, regarding the PPI analysis, it revealed that for the full sample, the connectivity between the left angular gyrus seed and the left ventrolateral PFC (vlPFC) was significantly higher in controls compared to patients with OCD for the contrast Maintain > Observe, while the opposite pattern was found for Regulate > Maintain (increased connectivity in patients with OCD). When exploring the different strategy subgroups, an increased connectivity was found between the left amygdala seed and both the right inferior temporal gyrus (ITG) and the left middle occipital gyrus (MOG) for the Distancing subgroup and the Maintain > Observe contrast. Moreover, the connectivity of this same seed with the right dorsolateral PFC (dlPFC), the right caudate tail and the left medial PFC was also increased in patients for the Both strategies subgroup and the Regulate > Maintain contrast. Finally, for the Reinterpretation subgroup, the connectivity between the medial PFC seed and the right precentral gyrus was significantly higher in controls compared to patients with OCD for the contrast Regulate > Maintain (Table 3 and Figure 4).

In summary, the whole-brain task activation analysis showed no significant between-group differences for the full sample, but subgroup analyses highlighted specific differences tied to the emotion regulation strategy employed. For example, the Reinterpretation strategy revealed decreased precuneus activation in OCD patients, while the Both strategies subgroup showed increased activation in regions such as the posterior insula and precentral gyri in OCD patients for the Maintain > Observe contrast. These findings point to potential strategy-specific neural alterations in OCD, which interestingly are evident not when regulating emotions (Regulate > Maintain contrast) but when experiencing them (Maintain > Observe contrast). This points towards a general effect on emotional processing of having different approaches to emotion regulation. Functional connectivity analyses (PPI) offered further insights, revealing altered connectivity patterns in OCD patients. Notably, the left angular gyrus-vlPFC network showed reduced connectivity in OCD patients for the Maintain > Observe contrast, while the Regulate > Maintain contrast exhibited the opposite pattern. Subgroup analyses identified additional disruptions in connectivity linked to the amygdala and medial PFC seeds, with controls demonstrating stronger connectivity in key regulatory networks, particularly when engaging in the Reinterpretation strategy.

Figure 2: Behavioral results. Mean (95% Confidence Interval) in-scanner emotional ratings for each group and each condition (1 being 'neutral' and 5 being 'extremely negative'), for the full sample (top), as well as for the different subgroups depending on the emotion regulation strategy used (bottom). Abbreviations: HC = healthy control; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: fMRI task activation results. Between-group differences in whole-brain activation for the Reinterpretation and the Both strategies subgroups for the Maintain > Observe contrast. Findings are significant at the whole-brain level p < .05 FWE-cluster corrected Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: fMRI task psychophysiological interaction results. Between-group differences in whole-brain connectivity for the full sample and the different strategy subgroups for the left angular gyrus (2), the left amygdala (3), and the medial PFC (5) seeds. Seeds are represented in red, while regions with differential connectivity are represented in yellow (OCD > HC) or blue (HC > OCD) for the Maintain > Observe contrast, and in green (OCD > HC) or purple (HC > OCD) for the Regulate > Maintain contrast. Findings are significant at the whole-brain level p < .05 FWE-cluster corrected. See Table 3 for findings surviving an additional Bonferroni correction by the number of seeds explored. Abbreviations: HC = healthy control; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Table 2: Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants. Total N = 58 for the OCI-R subscales, N = 57 for the in-scanner emotional ratings, and N = 54 for the strategy used during the task. Abbreviations: AP = anti-psychotics; Dist = distancing; ERQ = Emotion Regulation Questionnaire; HC = healthy controls; OCD = obsessive-compulsive disorder; OCI-R = Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised; Reint = reinterpretation; SD = standard deviation; SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors; Y-BOCS = Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale. Please click here to download this Table.

Table 3: fMRI task results. Between-group differences in task activation and psychophysiological interaction analysis for the full sample as well as for the different strategy subgroups. Findings are significant at the whole-brain level p < .05 FWE-cluster corrected. *PPI findings that remain significant after an additional Bonferroni correction by the number of seeds explored (p < .05 / 6 = p < .0083). Abbreviations: dlPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; HC, healthy controls; ITG, inferior temporal gyrus; Ke, cluster extent in voxels; MNI, Montreal Neurological Institute; MOG, middle occipital gyrus; OCD, obsessive-compulsive disorder; PFC, prefrontal cortex; PPI, psychophysiological interaction analysis; vlPFC, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. Please click here to download this Table.

Supplementary File 1: Sociodemographic questionnaire used (in Portuguese), accompanied by a translation to English. Please click here to download this File.

Supplementary File 2: Clinical questionnaire used (in Portuguese), accompanied by a translation to English. Please click here to download this File.

Supplementary File 3: Portuguese version of the OCI-R used, accompanied by a translation to English. Please click here to download this File.

Supplementary File 4: Portuguese version of the ERQ used, accompanied by a translation to English. Please click here to download this File.

Supplementary File 5: Portuguese version of the Y-BOCS used, accompanied by a translation to English. Please click here to download this File.

Supplementary File 6: Presentation used for explaining the cognitive reappraisal task and train participants on distancing and reinterpretation strategies before scanning, accompanied by a translation to English. Please click here to download this File.

Supplementary File 7: IAPS neutral pictures used for the Observe condition of the cognitive reappraisal task. Please click here to download this File.

Supplementary File 8: IAPS negative pictures used for the Maintain condition of the cognitive reappraisal task. Please click here to download this File.

Supplementary File 9: IAPS negative pictures used for the Regulate condition of the cognitive reappraisal task. Please click here to download this File.

Supplementary File 10: Questionnaire used after the MRI session to check that participants adequately performed the task and note which strategies they used, accompanied by a translation to English. Please click here to download this File.

Supplementary File 11: Detailed software steps for the different data analyses included in this study. Please click here to download this File.

Discussion

This protocol allows researchers to explore the neural correlates of emotion regulation in patients with OCD in comparison to controls, using an fMRI cognitive reappraisal task. This design shows potential for enhancing our understanding of the brain's mechanisms for regulating emotions through deliberate strategies and can be used in patients with OCD as well as other psychiatric populations. Moreover, we carefully designed the protocol using the latest neuroimaging gold standards (a multiband sequence, fMRIPrep preprocessing, and an appropriate multiple comparison correction method, for example). Particular care was taken to ensure that both participant groups were matched on sociodemographic variables and that participants with data of poor quality were excluded from the analysis.

Despite all these precautions, we had negative findings (i.e., no between-group differences) in some of the analyses. At the behavioral level, the group effect was non-significant in the analysis of in-scanner ratings using a 2 x 3 repeated-measures ANOVA for the full sample. This finding aligns with previous meta-analyses and systematic reviews in psychiatric populations23,44, suggesting potential influences from social desirability effects, intra-scanner behavioral assessments, or impaired self-awareness of emotional experience. However, significant group differences emerged in the Success variable, indicating that individuals with OCD exhibited worse emotion regulation. Thus, despite an overall similarity in the pattern of ratings across conditions for both groups, alterations are still observable when concentrating on the Maintain and Regulate conditions only.

Moreover, when repeating this analysis for the different emotion regulation subgroups, the Reinterpretation subgroup was the only one showing the same pattern of findings as for the full sample, while the Distancing and the Both strategies subgroups did not show successful emotion regulation based on the in-scanner ratings, nor statistically significant differences between groups for the success variable. This points towards a beneficial impact of using reinterpretation strategies during this task both for ensuring successful emotion regulation in general, and for detecting significant differences between control and patient groups. In any case, the general findings suggest limited evidence for cognitive reappraisal deficits in OCD patients, which may be more pronounced when confronting symptom-specific stimuli (such as images with specific symptom content45), contrasting with relatively preserved reappraisal abilities when exposed to stimuli of general negative content.

The modest difference in the success in regulating emotions did not correspond to significant differences in brain activation when analyzing the full sample. Nevertheless, when specifically focusing in the Reinterpretation subgroup, patients with OCD showed decreased activation in the precuneus when experiencing emotions in comparison to controls. The precuneus, as part of the default mode network (DMN), is a region critically involved in self-referential processing46, and this could reflect a better ability of the controls who use reinterpretation strategies to adapt to the task demands, properly engaging in emotional processing during the Maintain condition (while OCD patients fail to do so). Regarding PPI analysis, it revealed connectivity differences for the full sample between regions of the left frontoparietal network, particularly between the left angular gyrus and the left vlPFC-regions critical for selective attention, cognitive control, and working memory47,48. While the absence of task-related fMRI activation differences for the full sample alongside significant connectivity alterations in the frontoparietal network might initially appear contradictory, we argue that this underscores the relevance of employing different neuroimaging analyses. Such approaches yield distinct insights, suggesting that certain neuroimaging modalities and analytical methods might be required to detect specific alterations. Moreover, further differences were found by the emotion regulation subgroup analyses, identifying additional disruptions in connectivity linked to the amygdala and medial PFC seeds, with controls demonstrating stronger connectivity in key regulatory networks, particularly when engaging in the Reinterpretation strategy.

Taken together, these findings suggest that emotion regulation deficits in OCD are not global but are context- and strategy-dependent. While some neural networks supporting emotion regulation remain functional, others exhibit distinct alterations, particularly in response to specific strategies. These results highlight the importance of considering individual differences in emotion regulation strategies and the neural mechanisms underlying these processes when evaluating OCD. Future studies should explore the impact of symptom-specific stimuli and examine potential therapeutic interventions targeting these disrupted networks.

A further consideration pertains to the task's design limitations, as it inherently poses a challenge to assess participants' engagement and performance in experiencing and regulating emotion. To attempt to mitigate this limitation, we conducted a postMRI interview asking participants which emotion regulation strategies they used during the task and excluded those participants who did not adequately perform the task. In this line, future studies using similar designs could enhance robustness by incorporating objective psychophysiological measures like heart-rate variability, which could offer more reliable assessments of emotion regulation performance. Moreover, we attempted to disentangle the differential behavioral and neural effects of using reinterpretation or distancing strategies (or both), but future studies better powered for these analyses will shed light on the robustness and replicability of our preliminary findings.

Disclosures

In the past 3 years, PM has received grants, CME-related honoraria, or consulting fees from Angelini, AstraZeneca, Bial Foundation, Biogen, DGS-Portugal, FCT, FLAD, Janssen-Cilag, Gulbenkian Foundation, Lundbeck, Springer Healthcare, Tecnimede, and 2CA-Braga.

Acknowledgements

This work has been funded by Portuguese National funds through the Foundation for Science and Technology (FCT) - project UIDB/50026/2020 (DOI 10.54499/UIDB/50026/2020), UIDP/50026/2020 (DOI 10.54499/UIDP/50026/2020), and LA/P/0050/2020 (DOI 10.54499/LA/P/0050/2020), and by the project NORTE-01-0145-FEDER-000039, supported by Norte Portugal Regional Operational Programme (NORTE 2020) under the PORTUGAL 2020 Partnership Agreement through the European Regional Development Fund (ERDF). MPP was supported by a grant RYC2021-031228-I funded by MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by the "European Union NextGenerationEU/PRTR".

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| AFNI | National Institute of Mental Health | RRID:SCR_005927 | https://afni.nimh.nih.gov/ |

| Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders | American Psychiatric Association | 5th edition | |

| fMRIPrep | NiPreps Community | RRID:SCR_016216 | Based on Nipype (RRID:SCR_002502). Pipeline details: https://fmriprep.org/en/stable/workflows.html |

| FSL | FMRIB Software Library, Analysis Group, FMRIB, Oxford | ||

| JASP | JASP Team, University of Amsterdam, the Netherlands | ||

| Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanner | Siemens | Verio 3T | |

| MRI-compatible response pad | Lumina–Cedrus Corporation | ||

| PsychoPy3 | University of Nottingham | ||

| SPM12 | Wellcome Trust Center for Neuroimaging | https://www.fil.ion.ucl. ac.uk/spm/ |

References

- Buckholtz, J. W., Meyer-Lindenberg, A. Psychopathology and the human connectome: toward a transdiagnostic model of risk for mental illness. Neuron. 74 (6), 990-1004 (2012).

- Menon, V. Large-scale brain networks and psychopathology: a unifying triple network model. Trends Cogn Sci. 15 (10), 483-506 (2011).

- Picó-Pérez, M. et al. Neural predictors of cognitive-behavior outcome in anxiety-related disorders: a meta-analysis of task-based fMRI studies. Psychol Med. 53 (8), 3387-3395 (2023).

- Gross, J. J. Antecedent- and response-focused emotion regulation: Divergent consequences for experience, expression, and physiology. J Pers Soc Psychol. 74 (1), 224-237 (1998).

- Ochsner, K., Silvers, J., Buhle, J. Functional imaging studies of emotion regulation: A synthetic review and evolving model of the cognitive control of emotion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1252, 1-35 (2012).

- Buhle, J. T. et al. Cognitive reappraisal of emotion: A meta-analysis of human neuroimaging studies. Cereb Cortex. 24 (11), 2981-2990 (2013).

- Frank, D. W. et al. Emotion regulation: Quantitative meta-analysis of functional activation and deactivation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 45, 202-211 (2014).

- Dosenbach, N. U. F. et al. Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 104 (26), 11073-11078 (2007).

- Ochsner, K. N., Gross, J. J. The neural bases of emotion and emotion regulation: A valuation perspective. Gross, J. J. (ed) Handbook of emotion regulation. The Guilford Press, 23-42 (2014).

- Morawetz, C., Bode, S., Baudewig, J., Kirilina, E., Heekeren, H. R. Changes in effective connectivity between dorsal and ventral prefrontal regions moderate emotion regulation. Cereb Cortex. 26 (5), 1923-1937 (2016).

- Steward, T. et al. Dynamic neural interactions supporting the cognitive reappraisal of emotion. Cereb Cortex. 31 (2), 961-973 (2021).

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. (2013).

- Schienle, A., Schäfer, A., Stark, R., Walter, B., Vaitl, D. Neural responses of OCD patients towards disorder-relevant, generally disgust-inducing and fear-inducing pictures. Int J Psychophysiol. 57 (1), 69-77 (2005).

- van den Heuvel, O. A. et al. Amygdala activity in obsessive-compulsive disorder with contamination fear: a study with oxygen-15 water positron emission tomography. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 132 (3), 225-237 (2004).

- Picó-Pérez, M. et al. Modality-specific overlaps in brain structure and function in obsessive-compulsive disorder: Multimodal meta-analysis of case-control MRI studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 112, 83-94 (2020).

- Goldberg, X. et al. Inter-individual variability in emotion regulation: Pathways to obsessive-compulsive symptoms. J Obsessive Compuls Relat Disord. 11, 105-112 (2016).

- Mataix-Cols, D., van den Heuvel, O. A. Common and distinct neural correlates of obsessive-compulsive and related disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2 9 (2), 391-410 (2006).

- Milad, M. R., Rauch, S. L. Obsessive-compulsive disorder: beyond segregated cortico-striatal pathways. Trends Cogn Sci. 16 (1), 43-51 (2012).

- Paul, S., Simon, D., Endrass, T., Kathmann, N. Altered emotion regulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder as evidenced by the late positive potential. Psychol Med. 46 (1), 137-147 (2016).

- Franklin, M. E., Foa, E. B. Treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder. Annual review of clinical psychology. 7, 229-243 (2011).

- Hu, T. et al. Relation between emotion regulation and mental health: a meta-analysis review. Psychol Rep. 114 (2), 341-362 (2014).

- Phillips, M. L., Drevets, W. C., Rauch, S. L., Lane, R. Neurobiology of emotion perception II: implications for major psychiatric disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 54 (5), 515-528 (2003).

- Picó-Pérez, M., Radua, J., Steward, T., Menchón, J. M., Soriano-Mas, C. Emotion regulation in mood and anxiety disorders: A meta-analysis of fMRI cognitive reappraisal studies. Prog Neuro-Psychopharmacology Biol Psychiatry. 79, 96-104 (2017).

- de Wit, S. J. et al. Multicenter voxel-based morphometry mega-analysis of structural brain acans in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 171 (3), 340-349 (2014).

- Ferreira, S. et al. Frontoparietal hyperconnectivity during cognitive regulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder followed by reward valuation inflexibility. J Psychiatr Res. 137, 657-666 (2020).

- Menzies, L. et al. Integrating evidence from neuroimaging and neuropsychological studies of obsessive-compulsive disorder: The orbitofronto-striatal model revisited. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 32 (3), 525-549 (2008).

- Huyser, C., Veltman, D. J., Wolters, L. H., De Haan, E., Boer, F. Functional magnetic resonance imaging during planning before and after cognitive-behavioral therapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 49 (12), 1238-1248.e5 (2010).

- Vriend, C. et al. Switch the itch: A naturalistic follow-up study on the neural correlates of cognitive flexibility in obsessive-compulsive disorder. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 213 (1), 31-38 (2013).

- Fink, J., Pflugradt, E., Stierle, C., Exner, C. Changing disgust through imagery rescripting and cognitive reappraisal in contamination-based obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 54, 36-48 (2018).

- Sheehan, D. V. et al. The Mini-International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): The development and validation of a structured diagnostic psychiatric interview for DSM-IV and ICD-10. J Clin Psychiatry. 59 (suppl 20), 11980 (1998).

- Foa, E. B. et al. The obsessive-compulsive inventory: Development and validation of a short version. Psychol Assess. 14 (4), 485-496 (2002).

- Varela Cunha, G. et al. The Obsessive-Compulsive Inventory-Revised (OCI-R): Translation and validation of the European Portuguese version. Acta Med Port. 36 (3), 174-182 (2023).

- Gross, J. J., John, O. P. Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: implications for affect, relationships, and well-being. J Pers Soc Psychol. 85 (2), 348-362 (2003).

- Vaz, F. M., Martins, C., Martins, E. C. Diferenciação emocional e regulação emocional em adultos portugueses. PSICOLOGIA. 22 (2), 123-135 (2008).

- Goodman, W. K. et al. The Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 46 (11), 1006 (1989).

- Castro-Rodrigues, P. et al. Criterion validity of the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale second edition for diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive disorder in adults. Front Psychiatry. 9, 431 (2018).

- Phan, K. L. et al. Neural substrates for voluntary suppression of negative affect: A functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Biol Psychiatry. 57 (3), 210-219 (2005).

- Lang, P., Bradley, M., Cuthbert, B. International Affective Picture System (IAPS): Digitized photographs, instruction manual and affective ratings. Technical Report A-6. Gainesville, FL: University of Florida (2005).

- Peirce, J.W. PsychoPy-Psychophysics software in Python. J Neurosci Methods. 162 (1-2), 8-13 (2007).

- Esteban, O. et al. fMRIPrep: a robust preprocessing pipeline for functional MRI. Nat Methods. 16 (1), 111-116 (2019).

- Esteban, O. et al. Analysis of task-based functional MRI data preprocessed with fMRIPrep. Nat Protoc. 15 (7), 2186-2202 (2020).

- Jenkinson, M., Beckmann, C. F., Behrens, T. E. J., Woolrich, M. W., Smith, S. M. FSL. NeuroImage. 62 (2), 782-790 (2012).

- Cox, R. W. AFNI: software for analysis and visualization of functional magnetic resonance neuroimages. Comput Biomed Res. 29 (29), 162-173 (1996).

- Zilverstand, A., Parvaz, M. A., Goldstein, R. Z. Neuroimaging cognitive reappraisal in clinical populations to define neural targets for enhancing emotion regulation. A systematic review. Neuroimage. 151, 105-116 (2017).

- Thorsen, A. L. et al. Emotion regulation in obsessive-compulsive disorder, unaffected siblings, and unrelated healthy control participants. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 4 (4), 352-360 (2019).

- Utevsky, A. V., Smith, D. V., Huettel, S. A. Precuneus is a functional core of the default-mode network. J Neurosci. 34 (3), 932 (2014).

- Aron, A. R., Robbins, T. W., Poldrack, R. A. Inhibition and the right inferior frontal cortex: one decade on. Trends Cogn Sci. 18 (4), 177-185 (2014).

- Pessoa, L., Kastner, S., Ungerleider, L. G. Neuroimaging studies of attention: from modulation of sensory processing to top-down control. J Neurosci. 23 (10), 3990-3998 (2003).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved