需要订阅 JoVE 才能查看此. 登录或开始免费试用。

Method Article

用于测定金属结合寡聚肽的金属电子识别和机制的Ion流动性-质谱技术

摘要

Ion 流动性质谱和分子建模技术可以描述设计金属结合肽和铜结合肽美他可辛的选择性金属结合性能。开发新的金属包合肽类将有助于治疗与金属子失平衡相关的疾病。

摘要

电喷雾电位化(ESI)可以将水相肽或肽复合物转移到气相,同时保存其质量、总电荷、金属结合相互作用和构象形状。ESI 与电子流动性质谱法 (IM-MS) 耦合提供了一种工具技术,允许同时测量肽的量位 (m/z) 和碰撞横截面 (CCS),和构象形状。肽复合物的总体电荷由肽的酸性和基本位点1)和2)金属电的氧化状态控制。因此,复合物的总体电荷状态是影响肽金属电结合亲和力的溶液的pH的函数。对于 ESI-IM-MS 分析,肽和金属离子溶液由仅水溶液制备,pHH 与稀水醋酸或氢氧化铵一起调整。这允许为特定的肽确定pH依赖性和金属电位选择性。此外,肽复合物的m/z和CCS可与B3LYP/LanL2DZ分子建模一起使用,以识别该复合物的金属电协调结合点位和三级结构。结果表明,ESI-IM-MS如何描述一组替代的美他可辛肽的选择性结合性能,并将其与铜结合肽美他可曲蛋白进行比较。

引言

铜和锌离子对生物体至关重要,对包括氧化保护、组织生长、呼吸、胆固醇、葡萄糖代谢和基因组读数1在内的过程至关重要。为了启用这些功能,组,如Cys的硫酸盐,他的2,3,(更罕见)的硫丹,和Glu和Asp的甲苯选择性地将金属作为辅助因子到活动位点金属酶。这些协调小组的相似性提出了一个耐人寻味的问题,即他和Cys配体如何选择性地将Cu(I/II)或Zn(II)纳入,以确保正确的功能。

选择性结合通常通过获取和贩运肽来完成,这种肽控制锌(II)或Cu(I/II)的i/II)子浓度4。Cu(I/II)具有高度反应性,对酶造成氧化损伤或异化结合,因此其自由浓度受到铜伴和铜调节蛋白的严格调节,这些蛋白质安全地将其输送到细胞中的各个位置,并紧密地调节控制其平衡5,6。铜代谢或平衡的中断与门克斯和威尔逊的疾病7以及癌症7和神经紊乱直接相关,如普里昂8和阿尔茨海默氏病9。

Wilson 的疾病与眼睛、肝脏和大脑部分的铜含量增加有关,其中 Cu(I/II) 的氧化还原反应产生活性氧,导致肝神经退化。现有的包合疗法是小的三醇氨基酸阴西胺和三甲四胺。或者,甲抗凝铜采集肽甲酰沙棘素(mb)10,11表现出治疗潜力,因为它们对Cu(I)12具有高结合亲和力。当甲基三磷酸三甲杆菌OB3b的甲胺素(mb-OB3b)在威尔逊病的动物模型中被研究时,铜有效地从肝脏中取出,并通过胆汁13排泄。体外实验证实,mb-OB3b可以从肝细胞醇13中所含的铜金属醇素中洗去铜。激光消融电耦合等离子体质谱成像技术研究了威尔逊病肝样本14、15、16中铜的空间分布,并表明mb-OB3b去除铜与短处理期只有8天17。

mb-OB3b还将与其他金属离子结合,包括Ag(I)、Au(III)、Pb(II)、Mn(II)、Co(II)、Fe(II)、Ni(II)和Zn(II)18、19。Ag(I)展示的生理Cu(I)结合位点的竞争,因为它可以取代Cu(I)从mb-OB3b复合体,与Ag(I)和Ni(II)也表现出不可逆转的绑定Mb,不能取代Cu(I)19。最近,研究了一系列具有2His-2Cys结合图案的甲酰亚布辛(amb)寡肽,其锌(II)和Cu(I/II)结合特性具有特征。他们的主要氨基酸序列是相似的,他们都包含2His-2Cys主题,Pro和乙酰化N-总站。它们主要不同于mb-OB3b,因为2His-2Cys图案取代了mb-OB3b的两个enethiol牛酮结合位点。

电喷雾电位化与电力流动性质谱(ESI-IM-MS)相结合,为确定肽的金属结合特性提供了强大的工具技术,因为它测量其质量电荷(m/z)和碰撞横截面 (CCS),同时从溶液相中保存其质量、电荷和构象形状。m/z和 CCS 与肽体测定学、原形状态和构象形状有关。由于明确确定了物种中每个元素的身份和数量,因此确定骨化学计量。肽复合物的总体电荷与酸性和基本位点的原位和金属电的氧化状态有关。CCS提供了肽复合物的构象形状信息,因为它测量了与复体三级结构相关的旋转平均大小。复合物的整体电荷状态也是pH的函数,影响肽的金属电结合亲和力,因为脱质子的基本或酸性位点,如carboxyl、His、Cys和Tyr也是金属电的的潜在结合位点。在分析中,肽和金属离子在水溶液中制备,pH由稀水性醋酸或氢氧化铵调整。这允许为肽确定pH依赖性和金属电位选择性。此外,ESI-IM-MS测定的m/z和CCS可与B3LYP/LanL2DZ分子建模一起使用,以发现复合体金属电一致的类型和三级结构。本文中显示的结果揭示了ESI-IM-MS如何描述一组amb肽的选择性包合性能,并将其与铜结合肽mb-OB3b进行比较。

研究方案

1. 试剂制备

- 培养甲基肌酸三角性四氯环带,分离无Cu(I)的mb-OB3b 18,22,23,冷冻干燥样品,并储存在-80°C,直到使用。

- 合成 amb 肽(>98% 纯度为 amb1,amb2,amb4;> 70% 纯度为 amb7),冷冻干燥样品,并将其储存在 -80°C 直到使用。

- 购买 >98% 纯度氯化锰(II)氯化物、氯化钴(II)氯化物、氯化铜(II)氯化物、硝酸铜(II)硝酸银、氯化锌(II)氯化物、氯化铁(III)和氯化铅(II)。

- 购买用作校准剂的聚DL-丙氨酸聚合物,用于测量amb物种的碰撞横截面和HPLC级或更高氢氧化铵、冰川醋酸和乙酰乙酰酯。

2. 准备库存解决方案

-

肽库存溶液

- 在 1.7 mL 塑料小瓶中,使用至少三个显著数字准确称量,即 10.0–20.0 mg 的 mb-OB3b 或 amb 的质量。

注:当添加1.00 mL的去离子(DI)水时,称重质量应产生12.5 mM或1.25 mM,具体取决于肽的溶解度。 - 使用移液器,在称重肽样品中加入 1.00 mL 的去离子水(>17.8 MΩ cm),以产生 12.5 mM 或 1.25 mM 溶液。将盖牢固放置,并彻底与至少 20 个反转混合。

- 使用微管将肽样品中的50.0 μL等分分分分分放入单独标记的1.5 mL小瓶中,并将其储存在-80°C,直到使用。

- 在 1.7 mL 塑料小瓶中,使用至少三个显著数字准确称量,即 10.0–20.0 mg 的 mb-OB3b 或 amb 的质量。

-

金属子架溶液

- 使用至少三个显著数字准确称量,在 1.7 mL 小瓶中,金属氯化物或硝酸银的质量为 10.0–30.0 mg。

注:添加 1.00 mL 的 DI 水时,称重质量应产生 125 mM。 - 将 1.00 mL 的 DI 水添加到 1.7 mL 小瓶中的称重金属样品中,以产生 125 mM 溶液。将盖牢固放置,并彻底与至少 20 个反转混合。

- 使用至少三个显著数字准确称量,在 1.7 mL 小瓶中,金属氯化物或硝酸银的质量为 10.0–30.0 mg。

- 氢氧化铵库存溶液:通过将DI水稀释99.5%醋酸溶液的57μL,最终体积达到1.00 mL,制备1.0M醋酸溶液。将 21% 氢氧化铵溶液中的 90 μL 与 DI 水稀释至 1.00 mL 的最终体积,制备 1.0 M 氢氧化铵溶液。通过采用 1.0 M 溶液的 100 μL 来制备 0.10 M 和 0.010 M 醋酸和氢氧化铵溶液,使每个溶液连续稀释两次。

- Poly-DL-丙氨酸库存溶液:通过称量1.0毫克PA并溶解在1.0 mL的DI水中,制备聚DL-丙氨酸(PA),以1,000ppm。彻底混合。使用微管,分配50.0μL等分,并分别放入1.7 mL小瓶中,储存在-80°C。

3. 电喷雾-电子流动性-质谱分析

- 用约 500 μL 的 0.1 M 冰川醋酸、0.1 M 氢氧化铵彻底清洁 ESI 入口管和针毛细管,最后清洁 DI 水。

- 解冻 1,000 ppm PA 库存溶液的 50.0 μL 等分,用 450 μL 的 DI 水稀释,使其达到 100 ppm PA。用500 μL的DI水和500μL的乙酰乙酰乙醚将其稀释至1.00 mL,以提供10ppm PA溶液。

- 使用讨论部分中所述的原生 ESI-IM-MS 条件,收集 10 ppm PA 溶液的负子和正组 IM-MS 光谱,每次 10 分钟。

- 解冻 12.5 mM 或 1.25 mM amb 库存溶液的 50.0 μL 等分,用 DI 水连续稀释,最终浓度为 0.125 mM amb。彻底混合每个稀释。

- 移液 100.0 μL 的 125 mM 金属孔积溶液,放入 1.7 mL 小瓶中,用 DI 水稀释至 1.00 mL,以产生 12.5 mM 金属孔。重复两个连续稀释,给出最终的0.125 mM金属离子浓度。彻底混合每个稀释。

- 将 0.125 mM amb 的移液 200.0 μL 放入 1.7 mL 小瓶中,用 500 μL 的 DI 水稀释,并将溶液彻底混合。

- 加入50μL的1.0M醋酸溶液,将样品的pH值调整到3.0。

- 将 0.125 mM 金属电的 200.0 μL 添加到 pH 调整样品中。加入DI水,产生1.00 mL的样品最终体积,彻底混合,并允许样品在RT时平衡10分钟。

- 使用钝鼻注射器采集500μL的样品,并收集负子和正电子(ES-IM-MS)光谱各5分钟。使用样品的剩余 500 μL 使用经过校准的微 pH 电极记录其最终 pH 值。

- 重复步骤 3.6-3.9,同时修改步骤 3.7,通过添加新体积的 0.010 M、0.10 M 或 1.0 M 醋酸或氢氧化铵溶液,将 pH 量调整为 4.0、5.0、6.0、7.0、8.0、9.0 或 10.0。

- 收集 10 ppm PA 溶液的负极和正电子管 ESI-IM-MS 光谱各 10 分钟。

4. 安布样品金属滴定的准备

- 按照步骤 3.1_3.5 中描述的步骤操作。

- 将 0.125 mM amb 的移液 200.0 μL 放入 1.7 mL 小瓶中,用 500.0 μL 的 DI 水稀释,并将溶液彻底混合。

- 加入0.010 M氢氧化铵溶液的80 μL,将样品的pH值调整为pH = 9.0。

- 加入0.125 mM金属电液的28 μL,以产生0.14摩尔当量的金属电偶,加入DI水,使样品的最终体积达到1.00 mL,彻底混合,并允许样品在RT时平衡10分钟。

- 使用钝鼻注射器采集500μL的样品,并收集负极和正的ESI-IM-MS光谱各5分钟。使用样品的剩余 500 μL 使用经过校准的微 pH 电极记录其最终 pH 值。

- 重复步骤 4.2_4.5,同时修改步骤 4.3 以添加 0.125 mM 金属 ion 溶液的适当体积,以提供 0.28、0.42、0.56、0.70、0.84、0.98、1.12、1.26 或 1.40 摩尔等价物。

- 收集 10 ppm PA 溶液的负子和正子 IM-MS 光谱,每次 10 分钟。

5. ESI-IM-MS pH 滴定数据分析

- 从IM-MS光谱中,通过将带电的abs物种与其理论m/z同位素模式相匹配来识别哪些带电的abs物种。

- 打开 MassLynx 并单击色度图以打开色度图窗口。

- 转到"文件"菜单并打开以查找并打开 IM-MS 数据文件。

- 通过右键单击并拖动色谱并释放 IM-MS 频谱。频谱窗口将打开,显示 IM-MS 频谱。

- 在频谱窗口中,单击工具和同位素模型。在同位素建模窗口中,输入 amb 物种的分子公式,检查显示充电电位框,然后进入充电状态。单击"确定"。

- 重复此操作以识别 IM-MS 光谱中的所有物种,并记录其 m/z 同位素范围。

- 对于每个 amb 物种,分离任何巧合的 m/z 物种,并使用其 m/z 同位素模式提取其到达时间分布 (ATD) 来识别它们。

- 在 MassLynx 中,单击漂移范围以打开程序。在 DriftScope 中,单击"文件并打开"以查找并打开 IM-MS 数据文件。

- 使用鼠标和左键单击放大 amb 物种的 m/z 同位素模式。

- 使用"选择"工具和鼠标左键选择同位素图案。单击"接受当前选择"按钮。

- 要分离任何巧合的 m/z 物种,请使用选择工具和鼠标左键选择 ATD 时间与 amb 物种的同位素模式对齐。单击"接受当前选择"按钮。

- 要导出 ATD,请访问文件 |导出到 MassLynx,然后选择"保留漂移时间"并将文件保存在相应的文件夹中。

- 确定 ATD 的质心,并将 ATD 曲线下的面积整合为物种种群的量度。

- 在 MassLynx 的色谱图窗口中打开保存的导出文件。点击流程 |从菜单集成。选中"顶点轨道峰值集成"框,然后单击"确定"。

- 记录心托 ATD (tA) 和集成区域,如色谱图窗口所示。对所有保存的 amb 和 PA IM-MS 数据文件重复上述步骤。

- 对每个滴定点处的正离子或负离子的所有提取的 amb 物种使用集成 ATD,以将其标准化为相对百分比刻度。

- 将amb物种的身份及其在每个pH的集成ATD输入电子表格。

- 对于每个 pH,使用集成的 ATD 的总和将单个 amb 的 ATD 规范化为百分比刻度。

- 在图表中绘制每个 amb 物种与 pH 的百分比强度,以显示每个物种的种群如何随 pH 的函数而变化。

6. 碰撞横截面

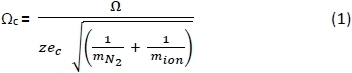

- 使用电子表格,使用下面的公式 1 将 PA 负25、26和正27离子的CCS (Ω) 转换为使用下面的公式1校正的 CCS(+c),其中:z = 离子电荷;ec = 电位(1.602×10-19 C);mN2 = N2气体(Da)的质量;和m子=子质量。29

- 使用下面的公式 2将 PA 校准剂和 amb 物种的平均到达时间 (tA) 转换为漂移时间 (tD),其中:c = 增强的占空比延迟系数 (1.41),m/z 是肽子的量为电荷。

- 绘制 PA 校准器 tD与其 +c。然后,使用下面所示的公式 3的最小二乘回归拟合,确定 A' 和 B 值,其中:A' 是温度、压力和电场参数的校正;和 B 补偿 IM 设备的非线性效应。

- 使用这些 A' 和 B 值以及来自 ambs ATD 的质心 tD值,使用公式 3确定它们的 + c,并使用公式 1确定它们的 +c。该方法为肽类提供CCS,估计绝对误差约为2%25,26,27。

7. 计算方法

- 使用B3LYP/LanL2DZ级理论,包括贝克3参数混合功能30和Dunning基础集31和电子核心电位32,33,34定位用于观测到的 m/z amb 物种35的所有可能协调类型的几何优化的构件。

注:有关如何生成和提交计算的详细信息,请参阅补充文件中的高斯视图用法。 - 比较每个构件的预测自由能量,并使用西格玛程序36中的电量Lennard-Jones(LJ)方法计算其理论CCS。

- 从最低的自由能量构算器中,确定哪个coners具有LJ CCS,该标准与IM-MS测量的CCS一致,以识别实验中观察到的构同器的三级结构和协调类型。

结果

amb1的金属绑定

Amb1的 IM-MS 研究20(图 1A) 显示,铜离子和锌离子以 pH 依赖性的方式结合到 amb1(图 2)。然而,铜和锌通过不同协调部位的不同反应机制与amb1结合。例如,将Cu(II)添加到amb1中,通过二硫化物桥形成导致amb1(amb 1ox)氧化,在pH>6时?...

讨论

关键步骤:通过 ESI-IM-MS 保存用于检查的解决方案阶段行为

必须使用本机 ESI 仪器设置来保存肽的化学测量、电荷状态和构象结构。对于原生条件,必须优化 ESI 源中的条件,如锥电压、温度和气体流量。此外,必须检查源、陷阱、电子移动性和传输移动波(尤其是控制注入电压进入 IM 单元的直流陷印偏置)中的压力和电压,以检查其对充电状态和电子移动分布的影响。

披露声明

作者没有什么可透露的。

致谢

此材料基于国家科学基金会支持的工作,包括 1764436、NSF 仪器支持 (MRI-0821247)、韦尔奇基金会 (T-0014) 以及能源部的计算资源 (TX-W-20090427-0004-50) 和 L3 通信.我们感谢鲍尔的加州大学圣巴巴拉分校小组分享了西格玛计划,阿约巴米·伊莱桑米在视频中演示了这项技术。

材料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| acetonitrile HPLC-grade | Fisher Scientific (www.Fishersci.com) | A998SK-4 | |

| ammonium hydroxide (trace metal grade) | Fisher Scientific (www.Fishersci.com) | A512-P500 | |

| cobalt(II) chloride hexahydrate 99.99% | Sigma-Aldrich (www.sigmaaldrich.com) | 255599-5G | |

| copper(II) chloride 99.999% | Sigma-Aldrich (www.sigmaaldrich.com) | 203149-10G | |

| copper(II) nitrate hydrate 99.99% | Sigma-Aldrich (www.sigmaaldrich.com) | 229636-5G | |

| designed amb1,2,3,4,5,6,7 peptides | Neo BioLab (neobiolab.com) | designed peptides were synthized by order | |

| designed amb5B,C,D,E,F peptides | PepmicCo (www.pepmic.com) | designed peptides were synthized by order | |

| Driftscope 2.1 software program | Waters (www.waters.com) | software analysis program | |

| Freeze-dried, purified, Cu(I)-free mb-OB3b | cultured and isolated in the lab of Dr. DongWon Choi (Biology Department, Texas A&M-Commerce) | ||

| glacial acetic acid (Optima grade) | Fisher Scientific (www.Fishersci.com) | A465-250 | |

| Iron(III) Chloride Anhydrous 98%+ | Alfa Aesar (www.alfa.com) | 12357-09 | |

| lead(II) nitrate ACS grade | Avantor (www.avantormaterials.com) | 128545-50G | |

| manganese(II) chloride tetrahydrate 99.99% | Sigma-Aldrich (www.sigmaaldrich.com) | 203734-5G | |

| MassLynx 4.1 | Waters (www.waters.com) | software analysis program | |

| nickel chloride hexahydrate 99.99% | Sigma-Aldrich (www.sigmaaldrich.com) | 203866-5G | |

| poly-DL-alanine | Sigma-Aldrich (www.sigmaaldrich.com) | P9003-25MG | |

| silver nitrate 99.9%+ | Alfa Aesar (www.alfa.com) | 11414-06 | |

| Waters Synapt G1 HDMS | Waters (www.waters.com) | quadrupole - ion mobility- time-of-flight mass spectrometer | |

| zinc chloride anhydrous | Alfa Aesar (www.alfa.com) | A16281 |

参考文献

- Dudev, T., Lim, C. Competition among Metal Ions for Protein Binding Sites: Determinants of Metal Ion Selectivity in Proteins. Chemical Reviews. 114 (1), 538-556 (2014).

- Sovago, I., Kallay, C., Varnagy, K. Peptides as complexing agents: Factors influencing the structure and thermodynamic stability of peptide complexes. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 256 (19-20), 2225-2233 (2012).

- Sóvágó, I., Várnagy, K., Lihi, N., Grenács, &. #. 1. 9. 3. ;. Coordinating properties of peptides containing histidyl residues. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 327, 43-54 (2016).

- Rubino, J. T., Franz, K. J. Coordination chemistry of copper proteins: How nature handles a toxic cargo for essential function. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 107 (1), 129-143 (2012).

- Robinson, N. J., Winge, D. R. Copper Metallochaperones . Annual Review of Biochemistry. 79, 537-562 (2010).

- Scheiber, I. F., Mercer, J. F. B., Dringen, R. Metabolism and functions of copper in brain. Progress in Neurobiology. 116, 33-57 (2014).

- Tisato, F., Marzano, C., Porchia, M., Pellei, M., Santini, C. Copper in Diseases and Treatments, and Copper-Based Anticancer Strategies. Medicinal Research Reviews. 30 (4), 708-749 (2010).

- Millhauser, G. L. Copper and the prion protein: Methods, structures, function, and disease. Annual Review of Physical Chemistry. 58, 299-320 (2007).

- Arena, G., Pappalardo, G., Sovago, I., Rizzarelli, E. Copper(II) interaction with amyloid-beta: Affinity and speciation. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 256 (1-2), 3-12 (2012).

- Kim, H. J., et al. Methanobactin, a copper-acquisition compound from methane-oxidizing bacteria. Science. 305 (5690), 1612-1615 (2004).

- Di Spirito, A. A., et al. Methanobactin and the link between copper and bacterial methane oxidation. Microbiology Molecular Biology Reviews. 80 (2), 387-409 (2016).

- Kenney, G. E., Rosenzweig, A. C. Chemistry and biology of the copper chelator methanobactin. ACS Chemical Biology. 7 (2), 260-268 (2012).

- Summer, K. H., et al. The biogenic methanobactin is an effective chelator for copper in a rat model for Wilson disease. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 25 (1), 36-41 (2011).

- Hachmoeller, O., et al. Investigating the influence of standard staining procedures on the copper distribution and concentration in Wilson's disease liver samples by laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 44, 71-75 (2017).

- Hachmoeller, O., et al. Spatial investigation of the elemental distribution in Wilson's disease liver after D-penicillamine treatment by LA-ICP-MS. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 44, 26-31 (2017).

- Hachmoeller, O., et al. Element bioimaging of liver needle biopsy specimens from patients with Wilson's disease by laser ablation-inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 35, 97-102 (2016).

- Mueller, J. C., Lichtmannegger, J., Zischka, H., Sperling, M., Karst, U. High spatial resolution LA-ICP-MS demonstrates massive liver copper depletion in Wilson disease rats upon Methanobactin treatment. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 49, 119-127 (2018).

- Choi, D. W., et al. Spectral and thermodynamic properties of Ag(I), Au(III), Cd(II), Co(II), Fe(III), Hg(II), Mn(II), Ni(II), Pb(II), U(IV), and Zn(II) binding by methanobactin from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 100, 2150-2161 (2006).

- McCabe, J. W., Vangala, R., Angel, L. A. Binding Selectivity of Methanobactin from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b for Copper(I), Silver(I), Zinc(II), Nickel(II), Cobalt(II), Manganese(II), Lead(II), and Iron(II). Journal of the American Society of Mass Spectrometry. 28, 2588-2601 (2017).

- Sesham, R., et al. The pH dependent Cu(II) and Zn(II) binding behavior of an analog methanobactin peptide. European Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 19 (6), 463-473 (2013).

- Wagoner, S. M., et al. The multiple conformational charge states of zinc(II) coordination by 2His-2Cys oligopeptide investigated by ion mobility - mass spectrometry, density functional theory and theoretical collision cross sections. Journal of Mass Spectrom. 51 (12), 1120-1129 (2016).

- Bandow, N. L., et al. Isolation of methanobactin from the spent media of methane-oxidizing bacteria. Methods in Enzymology. 495, 259-269 (2011).

- Choi, D. W., et al. Spectral and thermodynamic properties of methanobactin from γ-proteobacterial methane oxidizing bacteria: a case for copper competition on a molecular level. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 104 (12), 1240-1247 (2010).

- Pringle, S. D., et al. An investigation of the mobility separation of some peptide and protein ions using a new hybrid quadrupole/travelling wave IMS/oa-ToF instrument. International Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 261 (1), 1-12 (2007).

- Forsythe, J. G., et al. Collision cross section calibrants for negative ion mode traveling wave ion mobility-mass spectrometry. Analyst. 14 (20), 6853-6861 (2015).

- Allen, S. J., Giles, K., Gilbert, T., Bush, M. F. Ion mobility mass spectrometry of peptide, protein, and protein complex ions using a radio-frequency confining drift cell. Analyst. 141 (3), 884-891 (2016).

- Bush, M. F., Campuzano, I. D. G., Robinson, C. V. Ion Mobility Mass Spectrometry of Peptide Ions: Effects of Drift Gas and Calibration Strategies. Analytical Chemistry. 84 (16), 7124-7130 (2012).

- Salbo, R., et al. Traveling-wave ion mobility mass spectrometry of protein complexes: accurate calibrated collision cross-sections of human insulin oligomers. Rapid Communications in Mass Spectrometry. 26 (10), 1181-1193 (2012).

- Smith, D. P., et al. Deciphering drift time measurements from travelling wave ion mobility spectrometry-mass spectrometry studies. European Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 15 (2), 113-130 (2009).

- Becke, A. D. Density-functional thermochemistry. III. The role of exact exchange. Journal of Chemical Physics. 98 (7), 5648-5652 (1993).

- Dunning, T. H., Hay, P. J. Gaussian basis sets for molecular calculations. Modern Theoretical Chemistry. 3, 1-27 (1977).

- Hay, P. J., Wadt, W. R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for potassium to gold including the outermost core orbitals. Journal of Chemical Physics. 82 (1), 299-310 (1985).

- Hay, P. J., Wadt, W. R. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for the transition metal atoms scandium to mercury. Journal of Chemical Physics. 82 (1), 270-283 (1985).

- Wadt, W. R., Hay, P. J. Ab initio effective core potentials for molecular calculations. Potentials for main group elements sodium to bismuth. Journal of Chemical Physics. 82 (1), 284-298 (1985).

- . Gaussian 09, Revision C.01. Gaussian, Inc. , (2012).

- Wyttenbach, T., von Helden, G., Batka, J. J., Carlat, D., Bowers, M. T. Effect of the long-range potential on ion mobility measurements. Journal of the American Society of Mass Spectrometry. 8 (3), 275-282 (1997).

- Choi, D., et al. Redox activity and multiple copper(I) coordination of 2His-2Cys oligopeptide. Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 50 (2), 316-325 (2015).

- Rigo, A., et al. Interaction of copper with cysteine: stability of cuprous complexes and catalytic role of cupric ions in anaerobic thiol oxidation. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 98 (9), 1495-1501 (2004).

- Vytla, Y., Angel, L. A. Applying Ion Mobility-Mass Spectrometry Techniques for Explicitly Identifying the Products of Cu(II) Reactions of 2His-2Cys Motif Peptides. Analytical Chemistry. 88 (22), 10925-10932 (2016).

- Choi, D., Sesham, R., Kim, Y., Angel, L. A. Analysis of methanobactin from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b via ion mobility mass spectrometry. European Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 18 (6), 509-520 (2012).

- Martell, A. E., Motekaitis, R. J. NIST Standard Reference Database 46. Institute of Standards and Technology. , (2001).

- Pesch, M. L., Christl, I., Hoffmann, M., Kraemer, S. M., Kretzschmar, R. Copper complexation of methanobactin isolated from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b: pH-dependent speciation and modeling. Journal of Inorganic Biochemistry. 116, 55-62 (2012).

- Amin, E. A., Truhlar, D. G. Zn Coordination Chemistry: Development of Benchmark Suites for Geometries, Dipole Moments, and Bond Dissociation Energies and Their Use To Test and Validate Density Functionals and Molecular Orbital Theory. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 4 (1), 75-85 (2008).

- Sorkin, A., Truhlar, D. G., Amin, E. A. Energies, Geometries, and Charge Distributions of Zn Molecules, Clusters, and Biocenters from Coupled Cluster, Density Functional, and Neglect of Diatomic Differential Overlap Models. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 5 (5), 1254-1265 (2009).

- Lillo, V., Galan-Mascaros, J. R. Transition metal complexes with oligopeptides: single crystals and crystal structures. Dalton Transactions. 43 (26), 9821-9833 (2014).

- Choutko, A., van Gunsteren, W. F. Conformational Preferences of a beta-Octapeptide as Function of Solvent and Force-Field Parameters. Helvetica Chimica Acta. 96 (2), 189-200 (2013).

- Angel, L. A. Study of metal ion labeling of the conformational and charge states of lysozyme by ion mobility mass spectrometry. European Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 17 (3), 207-215 (2011).

- Kelso, C., Rojas, J. D., Furlan, R. L. A., Padilla, G., Beck, J. L. Characterisation of anthracyclines from a cosmomycin D-producing species of Streptomyces by collisionally-activated dissociation and ion mobility mass spectrometry. European Journal of Mass Spectrometry. 15 (2), 73-81 (2009).

- El Ghazouani, A., et al. Copper-binding properties and structures of methanobactins from Methylosinus trichosporium OB3b. Inorganic Chemistry. 50 (4), 1378-1391 (2011).

转载和许可

请求许可使用此 JoVE 文章的文本或图形

请求许可This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

版权所属 © 2025 MyJoVE 公司版权所有,本公司不涉及任何医疗业务和医疗服务。