Lymph Node Exam

Source: Richard Glickman-Simon, MD, Assistant Professor, Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Tufts University School of Medicine, MA

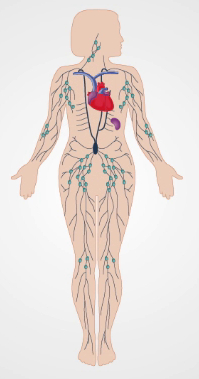

The lymphatic system has two main functions: to return extracellular fluid back to the venous circulation and to expose antigenic substances to the immune system. As the collected fluid passes through lymphatic channels on its way back to the systemic circulation, it encounters multiple nodes consisting of highly concentrated clusters of lymphocytes. Most lymph channels and nodes reside deep within the body and, therefore, are not accessible to physical exam (Figure 1). Only nodes near the surface can be inspected or palpated. Lymph nodes are normally invisible, and smaller nodes are also non-palpable. However, larger nodes (>1 cm) in the neck, axillae, and inguinal areas are often detectable as soft, smooth, movable, non-tender, bean-shaped masses imbedded in subcutaneous tissue.

Lymphadenopathy usually indicates an infection or, less commonly, a cancer in the area of lymph drainage. Nodes may become enlarged, fixed, firm, and/or tender depending on the pathology present. For example, a soft, tender lymph node palpable near the angle of the mandible may indicate an infected tonsil, whereas a firm, enlarged, non-tender lymph node palpable in the axilla of a female patient may be a sign of breast cancer.

Regional lymph nodes draining the area of a localized infection typically remain invisible but may become enlarged and tender on palpation. An infected wound or cellulitis may also result in lymphangitis or lymphadenitis, a condition in which the infection spreads along the chain of lymph channels and nodes. This may be accompanied by the appearance of red streaks and systemic symptoms such as fever, chills, and malaise. In rare cases, the intensity of the inflammatory reaction may cause the nodes to adhere to the surrounding soft tissue, fixing them in place.

Many metastatic cancers spread to regional lymph nodes first. Unlike infections, malignant cells invading lymph nodes may cause them to feel irregular and firm (even rock hard) but remain non-tender. If the cancer invades the outer capsules, nodes may become fixed to the surrounding soft tissue or matted together. Lymphoma, a primary cancer intrinsic to the lymphatic system, may be present anywhere in the body as single or multiple enlarged lymph nodes, which may become big enough to see on inspection, and are generally hard and non-tender on palpation. In addition to lymphoma, diffuse lymphadenopathy may be an indication of generalized infectious or inflammatory disorders such as HIV, mononucleosis, or sarcoidosis.

Figure 1. The Lymphatic System.

Because lymph nodes are distributed throughout the body, their evaluation usually takes place as part of the regional examinations of the head and neck, breast and axillae, upper extremities, external genitalia, and/or lower extremities. It is best to use the pads of the index and middle fingers to note the size, shape, number, pliability, texture, mobility, and tenderness of nodes bilaterally.

1. Lymph Nodes of the Head and Neck

Figure 2. Lymph Nodes of the Head and Neck.

- With the patient's neck flexed slightly forward, inspect for noticeably visible node enlargement.

- For each of the following steps, plan to palpate the head and neck nodes (Figure 2) with both hands, one on each side. In many cases, the nodes are not palpable.

- Palpate the preauricular, posterior auricular, and mastoid nodes in front of the ear, behind the ear, and superficial to the mastoid process, respectively.

- Palpate the occipital nodes posteriorly at the base of the skull.

- Palpate the tonsillar nodes located at the angle of mandible, the submandibular nodes midway between the angle and tip, and the submental nodes a few centimeters from the tip. Note that submandibular nodes need to be distinguished from the underlying submandibular gland, which is larger and lobulated.

- Palpate the anterior and superficial cervical nodes in front of and overlying the sternomastoid muscle, respectively. Deep cervical nodes, beneath the sternomastoid muscle, are rarely palpable.

- Palpate the posterior cervical nodes between the anterior edge of the trapezius and posterior edge of the sternomastoid.

- Palpate the supraclavicular nodes deep within the angle formed by the sternomastoid muscle and clavicle. Some lung and abdominal cancers metastasize to these nodes, so they may be discovered during the examination.

- Palpate the infraclavicular nodes on the underside of the clavicle.

2. Axillae and Upper Extremity

Figure 3. Axillary Lymph Nodes.

Three groups of axillary nodes - brachial, subscapular, and pectoral - drain their lymph into the central axillary nodes that lay deep within axilla against the chest wall about midway between the anterior and posterior axillary folds (Figure 3). These nodes, in turn, drain into the infraclavicular (apical) and supraclavicular nodes. Of the four axillary groups, only the central nodes are usually palpable. Since most breast cancers drain here, the axillary lymphatics need to be examined carefully, particularly in women. Most parts of the upper extremities drain more or less directly into the axillary lymph nodes. One exception is drainage from the ulnar aspects of the hand and forearm, which first encounters the epitrochlear nodes above the elbow.

- To examine the left axillary nodes, stand in front and to the left of the seated patient, supporting the patient's relaxed left arm at the wrist or elbow.

- Inform the patient that the exam may feel slightly uncomfortable.

- Reach your right hand up high in the left axilla, just behind the pectoralis muscle, with fingers pointing toward the mid-clavicle. Press your fingers against the chest wall, and slide them downward to feel the central nodes.

- If not done yet, palpate the infraclavicular (apical) and supraclavicular nodes.

- While still supporting the patient's left arm, palpate the epitrochlear nodes, which are located medially about 3 cm above the elbow.

- Repeat steps 2.1 - 2.5 for the patient's right axilla and upper extremity using your left hand.

3. Lower Extremities

Figure 4. Superficial Inguinal Lymph Nodes.

Superficial inguinal lymph nodes (Figure 4) are located high in the anterior thigh and drain various regions of the legs, abdomen, and perineum. These nodes are often large enough to palpate, even when normal.

- Have the patient lay supine with hips fully extended or slightly flexed.

- Palpate a horizontal group of nodes along and just inferior to the inguinal ligament. These nodes drain the superficial buttock and lower abdomen, external genitalia (excluding the testes), lower vagina, anal canal, and perianal area.

- Palpate a vertical group of nodes medial to the horizontal group just inferior to the femoral artery pulse. These nodes lie along the upper saphenous vein and drain the same regions of the lower extremities.

Most lymph nodes lie too deep to be accessible via physical examination. The superficial nodes are most efficiently assessed during regional examinations of the head and neck, breasts and axillae, upper extremities, lower extremities, and/or external genitalia. Because lymph nodes are constantly interacting with extracellular fluid draining from nearby tissues, their examination can provide information about the presence and status of infections or malignancies in the area. Nodes draining the site of a soft tissue infection are apt to become enlarged and tender but generally remain soft, smooth, and mobile. Hard, non-tender, matted, or fixed nodes are more typical of a spreading malignancy. Diffuse lymphadenopathy may indicate systemic diseases such as lymphomas, HIV, mononucleosis, or sarcoidosis. Finding a single abnormal node should prompt an examination of all nodes.