このコンテンツを視聴するには、JoVE 購読が必要です。 サインイン又は無料トライアルを申し込む。

Method Article

腎臓皮質細胞外マトリックス由来ハイドロゲルを製造

要約

ここで腎臓皮質細胞外マトリックス由来ハイドロゲル ネイティブ腎臓の細胞外マトリックス (ECM) 構造および生化学的組成を保持するを作製するためのプロトコルを提案する.作製プロセスとその応用を説明します。最後に、このゲルを使用して腎臓固有の細胞およびティッシュの再生とバイオ エンジニア リングをサポートする視点を説明します。

要約

細胞外マトリックス (ECM) は、組織の恒常性を維持するために重要な生物物理学的・生化学的手がかりを提供します。現在合成ハイドロゲルは、体外で細胞培養、細胞からの生理学的な行動を引き出すために必要なタンパク質とリガンド組成を欠いている機械の堅牢なサポートを提供しています。この原稿は、適切な機械的な堅牢性と支持の生化学的組成腎臓皮質 ECM から派生したハイドロゲルの作製方法をについて説明します。ヒドロゲルを作製するには、機械的に均質化と脱ひと腎臓皮質 ECM を可します。マトリックスも生理的機械剛性にゲル化を有効にするネイティブ腎臓皮質 ECM タンパク質比を維持します。ヒドロゲルは、生理的条件下で維持できる皮質細胞が腎臓に基板として機能します。さらに、腎臓病の今後の研究を可能にする病的環境をモデル化するゲル組成を操作できます。

概要

細胞外マトリックス (ECM) は、組織の恒常性を維持するために重要な生物物理学的・生化学的手がかりを提供します。複雑な分子の構成は、組織の構造と機能の両方のプロパティを調節します。構造タンパク質空間認識を細胞に提供し、の接着や移動の1を可能にします。バインドされた配位子は、2セルの動作を制御する細胞表面の受容体と対話します。腎臓 ECM 分子の組成と構造の解剖学的位置、発達段階と疾患状態3,4によって異なりますの茄多が含まれます。腎臓由来細胞で培養の研究に重要な側面は、ECM の複雑さをさたします。

ECM 微小をレプリケートする以前の試みは、recellularization のできる足場を作成する decellularizing の全体の組織に焦点を当てています。ドデシル硫酸ナトリウム (SDS) など化学洗剤または非イオン性洗剤で decellularization を実行し、それはどちらか全体の臓器灌流または液浸と撹拌方法5,6,7 を利用して ,8,9,10、11,12,13。ここに示す足場ネイティブ組織 ECM; は、構造および生化学的手がかりを保持します。さらに、ドナー固有のセルと recellularization は、臨床外科14,15,16,17,18, 19です。 ただし、これらの足場の構造の柔軟性を欠いているとの in vitro研究のため多くの現在のデバイスと互換性がありません。この制限を克服するために、多くのグループはさらにゲル20,21,22,23,24に脱 ECM を処理しています。これらのゲルは、射出成形、bioink と互換性のあるおよび細胞足場場所を脱マイクロ メートル スケールの空間的制約を回避します。さらに、分子組成とネイティブの ECM の比は、3、25が保持されます。ここで我々 は腎皮質 ECM (kECM) から派生したゲルを作製する方法を示します。

このプロトコルの目的は、腎臓の皮質領域の微小環境を複製するゲルを生成することです。腎臓皮質組織は、細胞内容物質を削除する定数撹拌下で 1 %sds の溶液で脱です。SDS は、免疫学的細胞材料6,7,9,26をすばやく削除する能力のための組織を decellularize に使用されます。KECM、機械の均質化と凍結乾燥5,6,9,11,26対象になります。ペプシンと強い酸で可溶化は、最終的なハイドロゲル原液20,27の結果します。ネイティブ kECM 蛋白質構造の重要なサポートし、信号の伝達3,25は保持されます。ヒドロゲルは、ネイティブのひと腎臓皮質28,29,30の一桁内にゲルことができます。この行列は、他のマトリックス蛋白質のゲルに比べて腎臓固有の細胞の活動の静穏化を維持するために使用されている生理学的な環境を提供します。さらに、マトリックス組成を通じて操作できます、たとえば、コラーゲン添加-私は、腎線維化およびその他の腎疾患31,32の研究モデル疾患環境に。

プロトコル

人間の腎臓は臓器調達機関の協会が定めた倫理的なガイドラインに従う LifeCenter 北西で隔離されました。このプロトコル ワシントン大学で動物のケアと細胞文化のガイドラインに従います。

1. ひと腎臓組織の準備

- Decellularization 溶液の調製

- 5000 mL ビーカー、70 × 10 mm 攪拌棒を滅菌します。

- 1: 1000 (重量: ボリューム) ドデシル硫酸ナトリウム (SDS) ビーカーに脱イオン水をオートクレーブをミックスします。約 200 rpm 24 h または SDS を完全に溶解するまで撹拌プレートにソリューションを残します。

注: 通常、1 %sds 溶液 2500 mL decellularize 単一ひと腎臓に十分です。 - 500 mL 滅菌真空フィルターに溶液を移し、滅菌密閉式コンテナーにフィルターを適用します。

- 腎臓組織の処理

- 2 つの止血鉗子のペア クランプの洗浄、オートクレーブは、一般的なサービス グレードはさみ、2 つのメス刃ハンドル、アルミ箔と 36 x 9 mm 攪拌棒で覆われて 1000 mL ビーカー

- Underpad、ティッシュ文化フードを行します。ビーカー、無菌培養皿 (150 x 25 mm)、および全体の腎臓器官をボンネットに配置します。1 %sds 溶液 500 ml ビーカーを入力します。

注: LifeCenter 北西から氷上人間の腎臓をいただきました。 - 滅菌のティッシュ文化皿 (図 1 a) で腎臓を配置します。すべての腎周囲の脂肪を削除するには、メス (図 1 b) と腎被膜周辺軽く剃毛します。

- メス、ちょうど腎臓の優れた終わり間で根本的な皮質組織を損傷することがなく腎被膜をこじ開けるに十分な深さの浅い 8-10 cm の切開を行います。腎被膜を削除するには、2 つの止血クランプ (図 1) で皮質組織から離れてそれを剥離します。

- (図 1) 腎臓の側面に沿ってメスを使用して、コロナの平面に沿って腎臓を二等分します。メス (図 1E) 髄質領域を切り開くによって両方の半分から皮質組織を分離し、0.5 cm3個セット (図 1 階) に皮質組織をサイコロします。任意の大規模な目に見える血管を削除します。

- 細胞外マトリックスの分離

- ティッシュ文化フード 1 %sds 溶液 500 mL と 1000 mL ビーカーをご記入ください。SDS 溶液ビーカーにさいの目に切った皮質組織と攪拌バーを配置します。オートクレーブのアルミ箔でビーカーをカバーし、ティッシュ文化フードの外約 400 rpm で攪拌プレートの上に置きます。

- 皮質組織した 24 時間撹拌プレートの後、ティッシュ文化フードにビーカーを持参し、ナイロン メッシュで作られた 40 μ m 無菌細胞ストレーナを追加します。漂白剤 200 ml 別 1000 mL ビーカーを入力し、ティッシュ文化フードに配置します。

- 漂白剤を含むビーカーにセル ストレーナーを介して SDS 溶液をピペットします。310 とセル ストレーナーだけビーカーになるまでのすべての SDS 溶液をピペットします。

注: セル ストレーナーは、ソリューション吸引中に削除されてから任意の組織を防ぐ必要があります。 - 新鮮な SDS 溶液 500 mL をビーカーで塗りつぶしセル ストレーナーを残します。同じアルミ箔でビーカーをカバーし前に、と同じ速度で撹拌プレートの上に置きます。

- 5 日間の合計のための手順 1.3.1-1.3.3 新鮮な SDS ソリューションでは 24 時間ごとを繰り返します。

- オートクレーブ ・ ディ ・水の 3 日間の合計、次の手順 1.3.1-1.3.3 のテクニックのすべての 24 h で脱組織をすすいでください。

- 脱組織細胞培養グレード水 2 日間合計、次の手順 1.3.1-1.3.3 のテクニックのすべての 24 h をすすいでください。

- 1.3.1-1.3.2 の手順を繰り返します。(呼ばれる kECM このポイントから上) 30 mL の円錐管が自立に decellularized 組織を転送し、すべての組織が水没するまで細胞培養グレードの水でそれを埋めます。

2. ハイドロゲル ストック溶液の作製

- 310 の機械加工

- ティッシュ文化フードの機械的に 2 分のティッシュのホモジェナイザーの円錐形の管の内で kECM を均質化します。

注: 均質化 kECM ECM のない目に見える部分と不透明なソリューションのようになります。 - もはや解決しない周囲のチューブを沸騰まで液体窒素で kECM を含む円錐管が水没します。一晩-4 ° C で kECM を格納します。

- ティッシュ文化フードの機械的に 2 分のティッシュのホモジェナイザーの円錐形の管の内で kECM を均質化します。

- 凍結脱組織の凍結乾燥

- 若干ガス交換を可能にする凍結乾燥機にチューブを配置し円錐管キャップを緩めます。3 日間または同じ白い粉末になるまで、kECM を凍結乾燥します。-4 ° C でストア。

- 化学的消化とゲルの可溶化

- オートクレーブ 20 mL シンチレーション バイアルとキャップ、15.9 × 7.9 mm 攪拌棒とファイン ・ チップ鉗子の一組。

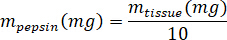

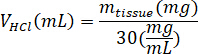

- 凍結乾燥 kECM の重量を量ると塩酸とペプシンmペプシンがペプシンの質量を次の数式を使用して 3% (30 mg/mL) 溶液に kECM の可溶化に必要な量のボリュームを計算、 m組織の質量凍結乾燥組織VHClは、0.01 N 塩酸の量。

- ティッシュ文化フードのシンチレーション バイアルにブタの胃のペプシン、0.01 N HCl と攪拌棒を追加し、すべてのペプシンが溶けるまで約 500 rpm で攪拌板にそれを残します。シンチレーション バイアル凍結乾燥 kECM に転送し、3 日間約 500 rpm で攪拌プレートに対してソリューションをおきます。

3. ゲルのゲル化

- 腎臓 ECM ハイドロゲル準備

- メディア サプリメント (M199) x 10、1 N NaOH で kECM ハイドロゲル原液を混合することによって、ゲルのゲルし、細胞培養媒体。氷の上のすべてのソリューションをしてください。

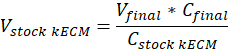

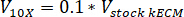

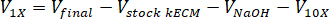

メモ: 最終的なゲル 7.5 mg/mL の濃度は、細胞培養に使用されました。kECM ゲルの 1 mL は提示細胞培養実験のために十分だった。 - V在庫 kECMは、必要に応じてストック kECM ハイドロゲルのボリューム、実行可能な kECM ジェルの量ストック kECM ハイドロゲルV最終が作成したゲル量次の式を使用して必要な量を判断C株式 kECMはストック kECM ハイドロゲルの濃度とC最後は最終的なゲルの濃度。

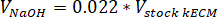

- 中和V水酸化ナトリウムが 1 N NaOH の量を次の式を使用して必要な試薬の量を決定する、 V10 Xは、M199 の体積 10 倍速のメディアを補完、そしてV1 Xが、細胞培養媒体の容積:

- ティッシュ文化フードのピペット滅菌 30 mL の円錐管が自立に中和試薬 (NaOH、M199、および細胞培養媒体) の。中和試薬溶液を混ぜて、microspatula。

- 1 mL の滅菌注射器を使用すると、中和試薬溶液に在庫 kECM ハイドロゲルの適切なボリュームを転送します。軽く混ぜ均一色ゲル溶液が得られるまでに、microspatula を使用します。

メモ: は、ゆっくりと静かに攪拌によって空気の泡を導入しないでください。 - KECM ハイドロゲルに細胞を組み込む、ステップ 3.1.1.3 中和のソリューション ボリューム計算からの細胞培養媒体 (V1 X) の 10 μ L を減算します。

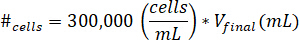

- 10 μ L の細胞培養媒体にセルを中断します。#セルが中断するセルの数を意味する次の方程式を使用して停止するセルの数を決定する、V最終が作成したゲルのボリューム。

注: 300,000 細胞/ml kECM ゲルで使用されるセルの濃度であります。 - KECM 原液を中和試薬溶液と混合されている後、最終 kECM ゲルに中断細胞液の 10 μ L をピペットします。セルが均等になるまで、microspatula を備えたソリューションをかき混ぜます。

- 10 μ L の細胞培養媒体にセルを中断します。#セルが中断するセルの数を意味する次の方程式を使用して停止するセルの数を決定する、V最終が作成したゲルのボリューム。

- メディア サプリメント (M199) x 10、1 N NaOH で kECM ハイドロゲル原液を混合することによって、ゲルのゲルし、細胞培養媒体。氷の上のすべてのソリューションをしてください。

- 1 mL の注射器を使用して kECM ハイドロゲルに目的のセル培養デバイスを塗りつぶします。

- 転送またはセルをめっきする前に 1 時間 37 ° C に設定するゲルを許可します。

結果

KECM ハイドロゲルは、ネイティブ腎臓の微小環境と類似の化学構造を持つ腎臓細胞培養のためのマトリックスを提供します。ヒドロゲルを作製するには、腎臓皮質組織は全体腎臓器官とさいの目に切った (図 1) から機械的に分離されます。洗剤粒子 (図 2 a.4 A.6) を除去する水でリンスが続く化学洗剤 (

ディスカッション

マトリックスは、細胞の挙動を支配する重要な機械および化学の手がかりを提供します。合成ハイドロゲルは、複雑な 3 次元パターンをサポートしますが、微小生体マトリックスは、多様な細胞の手がかりを提供するために失敗することができます。ネイティブの ECM から派生したゲルは、体内と体外の研究のための理想的な材料です。以前の研究はホスト免疫応答

開示事項

著者が明らかに何もありません。

謝辞

著者は、リンと幹細胞と再生医療 LifeCenter 北西の研究所のマイク ガービー イメージング研究室を確認したいと思います。彼らはまたへ北西腎臓の中心から制限されていないギフトと NIH T32 のトレーニングの許可 DK0007467 (R.J.N.) に DP2DK102258 (Y.Z.) に UH2/UH3 TR000504 (公団) に国立衛生研究所の助成金の助成を受けたい、腎臓研究所

資料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Preparation of Kidney Tissue | |||

| 5000 mL Beaker | Sigma-Aldrich | Z740589 | |

| Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate (SDS) | Sigma-Aldrich | 436143 | |

| Sterile H2O | Autoclaved DI H2O | ||

| Stir Bar (70 x 10 mm) | Fisher Science | 14-512-128 | |

| 500 mL Vacuum Filter | VWR | 97066-202 | |

| Stir Plate | Sigma-Aldrich | CLS6795420D | |

| 1000 mL Beaker | Sigma-Aldrich | CLS10031L | |

| Forceps | Sigma-Aldrich | F4642 | Any similar forceps may be used |

| Scissor-Handle Hemostat Clamp | Sigma-Aldrich | Z168866 | |

| Dissecting Scissors | Sigma-Aldrich | Z265977 | |

| Scalpel Handle, No. 4 | VWR | 25859-000 | Any similar scalpel handle may be used |

| Scalpel Blade, No. 20 | VWR | 25860-020 | Any similar scalpel blade may be used |

| Stir Bar (38.1 x 9.5 mm) | Fisher Science | 14-513-52 | |

| Absorbent Underpad | VWR | 82020-845 | |

| Petri Dish (150 x 25 mm) | Corning | 430597 | |

| Autoclavable Biohazard Bag | VWR | 14220-026 | |

| Sterile Cell Strainer (40 um) | Fisher Science | 22-363-547 | |

| Cell Culture Grade Water | HyClone | SH30529.03 | |

| 30 mL Freestanding Tube | VWR | 89012-778 | |

| Fabrication of ECM Gel | |||

| Tissue Homogenizer Machine | Polytron | PCU-20110 | |

| Freeze Dryer | Labconco | 7670520 | |

| 20 mL Glass Scintillation Vials and Cap | Sigma-Aldrich | V7130 | |

| Stir Bar (15.9 x 8 mm) | Fisher Science | 14-513-62 | |

| Pepsin from Porcine Gastric Mucosa | Sigma-Aldrich | P7012 | |

| 0.01 N HCl | Sigma-Aldrich | 320331 | Dilute to 0.01 N HCl with cell culuture water |

| Kidney ECM Gelation | |||

| 1 N NaOH (Sterile) | Sigma-Aldrich | 415413 | Dilute to 1 N in cell culture grade water |

| Medium 199 | Sigma-Aldrich | M4530 | |

| 15 mL Conical Tube | ThermoFisher | 339651 | |

| Cell Culture Media | ThermoFisher | 11330.032 | Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium: Nutrient Mixture F-12 (DMEM/F12) |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Gibco | 10082147 | |

| Antibiotic-Antimycotic 100X | Life Technologies | 15240-062 | |

| Insulin, Transferrin, Selenium, Sodium Pyruvate Solution (ITS-A) 100X | Life Technologies | 51300-044 | |

| 1 mL Syringe | Sigma-Aldrich | Z192325 | |

| Microspatula | Sigma-Aldrich | Z193208 |

参考文献

- Lelongt, B., Ronco, P. Role of extracellular matrix in kidney development and repair. Pediatric Nephrology. 18 (8), 731-742 (2003).

- Yue, B. Biology of the Extracellular Matrix: An Overview. Journal of Glaucoma. 23, S20-S23 (2014).

- Miner, J. H. Renal basement membrane components. Kidney International. 56 (6), 2016-2024 (1999).

- Petrosyan, A., et al. Decellularized Renal Matrix and Regenerative Medicine of the Kidney: A Different Point of View. Tissue Engineering Part B. 22 (3), 183-192 (2016).

- Caralt, M., et al. Optimization and Critical Evaluation of Decellularization Strategies to Develop Renal Extracellular Matrix Scaffolds as Biological Templates for Organ Engineering and Transplantation. American Journal of Transplantation. 15 (1), 64-75 (2015).

- Nakayama, K. H., Batchelder, C. A., Lee, C. I., Tarantal, A. F. Decellularized rhesus monkey kidney as a three-dimensional scaffold for renal tissue engineering. Tissue Engineering Part A. 16 (7), 2207-2216 (2010).

- Nakayama, K. H., Lee, C. C. I., Batchelder, C. A., Tarantal, A. F. Tissue Specificity of Decellularized Rhesus Monkey Kidney and Lung Scaffolds. Public Library of Science ONE. 8 (5), (2013).

- Orlando, G., et al. Production and implantation of renal extracellular matrix scaffolds from porcine kidneys as a platform for renal bioengineering investigations. Annals of Surgery. 256 (2), 363-370 (2012).

- Sullivan, D. C., et al. Decellularization methods of porcine kidneys for whole organ engineering using a high-throughput system. Biomaterials. 33 (31), 7756-7764 (2012).

- Choi, S. H., et al. Development of a porcine renal extracellular matrix scaffold as a platform for kidney regeneration. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 103 (4), 1391-1403 (2015).

- Ross, E. A., et al. Mouse stem cells seeded into decellularized rat kidney scaffolds endothelialize and remodel basement membranes. Organogenesis. 8 (2), 49-55 (2012).

- Nagao, R. J., et al. Decellularized Human Kidney Cortex Hydrogels Enhance Kidney Microvascular Endothelial Cell Maturation and Quiescence. Tissue Engineering Part A. 22 (19-20), 1140-1150 (2016).

- Gupta, S. K., Mishra, N. C., Dhasmana, A. Decellularization Methods for Scaffold Fabrication. Methods in Molecular Biology. , 1-10 (2017).

- Hudson, T., et al. Optimized Acellular Nerve Graft is Immunologically Tolerated and Supports Regeneration. Tissue Engineering. 10 (11), 1641-1651 (2004).

- Atala, A., Bauer, S. B., Soker, S., Yoo, J. J., Retik, A. B. Tissue-engineered autologous bladders for patients needing cystoplasty. Lancet. 367 (9518), 1241-1246 (2006).

- Ott, H. C., et al. Perfusion-decellularized matrix: using nature's platform to engineer a bioartificial heart. Nature Medicine. 14 (2), 213-221 (2008).

- Uygun, B., et al. Organ reengineering through development of a transplantable recellularied liver graft using decellularized liver matrix. Nature Medicine. 16 (7), 814-820 (2010).

- Nagao, R. J., et al. Preservation of Capillary-beds in Rat Lung Tissue Using Optimized Chemical Decellularization. Journal of Materials Chemistry B. 1 (37), 4801-4808 (2013).

- Song, J. J., et al. Regeneration and experimental orthotopic transplantation of a bioengineered kidney. Nature Medicine. 19 (5), 646-651 (2013).

- Freytes, D. O., Martin, J., Velankar, S. S., Lee, A. S., Badylak, S. F. Preparation and rheological characterization of a gel form of the porcine urinary bladder matrix. Biomaterials. 29 (11), 1630-1637 (2008).

- Wolf, M. T., et al. A hydrogel derived from decellularized dermal extracellular matrix. Biomaterials. 33 (29), 7028-7038 (2012).

- Fisher, M. B., et al. Potential of healing a transected anterior cruciate ligament with genetically modified extracellular matrix bioscaffolds in a goat model. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy. 20 (7), 1357-1365 (2012).

- Ghuman, H., et al. ECM hydrogel for the treatment of stroke: Characterization of the host cell infiltrate. Biomaterials. 91, 166-181 (2016).

- Rijal, G. The decellularized extracellular matrix in regenerative medicine. Regenerative Medicine. 12 (5), 475-477 (2017).

- Lennon, R., et al. Global Analysis Reveals the Complexity of the Human Glomerular Extracellular Matrix. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 25 (5), 939-951 (2014).

- Bonandrini, B., et al. Recellularization of Well-Preserved Acellular Kidney Scaffold Using Embryonic Stem Cells. Tissue Engineering Part A. 20 (9-10), 1486-1498 (2014).

- O'Neill, J. D., Freytes, D. O., Anandappa, A. J., Oliver, J. A., Vunjak-Novakovic, G. V. The regulation of growth and metabolism of kidney stem cells with regional specificity using extracellular matrix derived from kidney. Biomaterials. 34 (38), 9830-9841 (2013).

- Streitberger, K. -. J., et al. High-resolution mechanical imaging of the kidney. Journal of Biomechanics. 47 (3), 639-644 (2014).

- Bensamoun, S. F., et al. Stiffness imaging of the kidney and adjacent abdominal tissues measured simultaneously using magnetic resonance elastography. Clinical Imaging. 35 (4), 284-287 (2011).

- Moon, S. K., et al. Quantification of Kidney Fibrosis Using Ultrasonic Shear Wave Elastography. Journal of Ultrasound in Medicine. 34, 869-877 (2015).

- Genovese, F., Manresa, A. A., Leeming, D. J., Karsdal, M. A., Boor, P. The extracellular matrix in the kidney: a source of novel non-invasive biomarkers of kidney fibrosis?. Fibrogenesis & Tissue Repair. 7 (1), (2014).

- Hewitson, T. D. Fibrosis in the kidney: is a problem shared a problem halved?. Fibrogenes & Tissue Repair. 5 (1), S14 (2012).

- Wolf, M. T., et al. Polypropylene surgical mesh coated with extracellular matrix mitigates the host foreign body response. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 102 (1), 234-246 (2014).

- Faulk, D. M., et al. ECM hydrogel coating mitigates the chronic inflammatory response to polypropylene mesh. Biomaterials. 35 (30), 8585-8595 (2014).

- Jeffords, M. E., Wu, J., Shah, M., Hong, Y., Zhang, G. Tailoring Material Properties of Cardiac Matrix Hydrogels To Induce Endothelial Differentiation of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells. ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. 7 (20), 11053-11061 (2015).

- Kim, M. -. S., et al. Differential Expression of Extracellular Matrix and Adhesion Molecules in Fetal-Origin Amniotic Epithelial Cells of Preeclamptic Pregnancy. Public Library of Science ONE. 11 (5), e0156038 (2016).

- Paduano, F., Marrelli, M., White, L. J., Shakesheff, K. M., Tatullo, M. Odontogenic Differentiation of Human Dental Pulp Stem Cells on Hydrogel Scaffolds Derived from Decellularized Bone Extracellular Matrix and Collagen Type I. Public Library of Science ONE. 11 (2), e0148225 (2016).

- Viswanath, A., et al. Extracellular matrix-derived hydrogels for dental stem cell delivery. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 105 (1), 319-328 (2017).

- Uriel, S., et al. Extraction and Assembly of Tissue-Derived Gels for Cell Culture and Tissue Engineering. Tissue Engineering Part C Methods. 15 (3), 309-321 (2009).

- Saldin, L. T., Cramer, M. C., Velankar, S. S., White, L. J., Badylak, S. F. Extracellular matrix hydrogels from decellularized tissues: Structure and function. Acta Biomaterialia. 49, 1-15 (2017).

- Faust, A., et al. Urinary bladder extracellular matrix hydrogels and matrix-bound vesicles differentially regulate central nervous system neuron viability and axon growth and branching. Journal of Biomaterials Applications. 31 (9), 1277-1295 (2017).

- Pouliot, R. A., et al. Development and characterization of a naturally derived lung extracellular matrix hydrogel. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 104 (8), 1922-1935 (2016).

- Pati, F., et al. Printing three-dimensional tissue analogues with decellularized extracellular matrix bioink. Nature Communications. 5, 3935 (2014).

- Pati, F., et al. Biomimetic 3D tissue printing for soft tissue regeneration. Biomaterials. 62, 164-175 (2015).

- Wang, R. M., Christman, K. L. Decellularized myocardial matrix hydrogels: In basic research and preclinical studies. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 96, 77-82 (2016).

- Jang, J., et al. 3D printed complex tissue construct using stem cell-laden decellularized extracellular matrix bioinks for cardiac repair. Biomaterials. 112, 264-274 (2017).

- Frantz, C., Stewart, K. M., Weaver, V. M. The extracellular matrix at a glance. Journal of Cell Science. 123 (Pt 24), 4195-4200 (2010).

- Mouw, J. K., Ou, G., Weaver, V. M. Extracellular matrix assembly: a multiscale deconstruction. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 15 (12), 771-785 (2014).

- Bonnans, C., Chou, J., Werb, Z. Remodelling the extracellular matrix in development and disease. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 15 (12), 786-801 (2014).

- Hinderer, S., Layland, S. L., Schenke-Layland, K. ECM and ECM-like materials - Biomaterials for applications in regenerative medicine and cancer therapy. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 97, 260-269 (2016).

- Uriel, S., et al. The role of adipose protein derived hydrogels in adipogenesis. Biomaterials. 29 (27), 3712-3719 (2008).

- Singelyn, J. M., et al. Naturally derived myocardial matrix as an injectable scaffold for cardiac tissue engineering. Biomaterials. 30 (29), 5409-5416 (2009).

- Medberry, C. J., et al. Hydrogels derived from central nervous system extracellular matrix. Biomaterials. 34 (4), 1033-1040 (2013).

- Loneker, A. E., Faulk, D. M., Hussey, G. S., D'Amore, A., Badylak, S. F. Solubilized liver extracellular matrix maintains primary rat hepatocyte phenotype in-vitro. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part A. 104 (4), 957-965 (2016).

- Hill, R. C., Calle, E. A., Dzieciatkowska, M., Niklason, L. E., Hansen, K. C. Quantification of extracellular matrix proteins from a rat lung scaffold to provide a molecular readout for tissue engineering. Molecular & Cellular Proteomics. 14 (4), 961-973 (2015).

- Li, Q., et al. Proteomic analysis of naturally-sourced biological scaffolds. Biomaterials. 75, 37-46 (2016).

- Tanaka, T., Yada, R. Y. N-terminal portion acts as an initiator of the inactivation of pepsin at neutral pH. Protein Engineering. 14 (9), 669-674 (2001).

- Ligresti, G., et al. A Novel Three-Dimensional Human Peritubular Microvascular System. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 27 (8), 2370-2381 (2016).

- Mozes, M. M., Böttinger, E. P., Jacot, T. A., Kopp, J. B. Renal expression of fibrotic matrix proteins and of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-beta) isoforms in TGF-beta transgenic mice. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology. 10 (2), 271-280 (1999).

- Romanowicz, L., Galewska, Z. Extracellular matrix remodeling of the umbilical cord in pre-eclampsia as a risk factor for fetal hypertension. Journal of Pregnancy. 2011, 542695 (2011).

転載および許可

このJoVE論文のテキスト又は図を再利用するための許可を申請します

許可を申請さらに記事を探す

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2023 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved