Isolation and Culturing of Primary Murine Adipocytes from Lean and Obese Mice

* These authors contributed equally

In This Article

Summary

The size and fragility of mature adipocytes have limited the techniques and tools available for their study and isolation. Here, a protocol is described for the isolation of mature murine adipocytes, which can be easily adapted for different adipose depots and mouse diets.

Abstract

Adipose tissue is primarily composed of mature, lipid-laden adipocytes by volume. These postmitotic cells play a critical role in energy storage and mobilization, thermoregulation, and the secretion of endocrine factors. The expansion of white adipose tissue due to caloric imbalance results in both the enlargement of existing adipocytes and the generation of additional adipocytes from adipocyte progenitor cells. Obesity-driven changes to white adipose tissue, including those affecting adipocytes, are associated with numerous comorbidities, such as type 2 diabetes and 13 types of cancer. A significant barrier to studying how adipocytes contribute to disease is the inability to readily isolate and culture mature adipocytes. This article describes a protocol to isolate murine lean and obese adipocytes from the subcutaneous and visceral fat depots of male and female C57BL/6 mice. The protocol details how isolated primary adipocytes can be cultured in a membrane adipocyte aggregate system for up to 2 weeks, facilitating their functional analysis in co-culture experiments, lipolysis assays, or through the collection of conditioned media containing adipocyte-secreted factors. Additionally, the protocol outlines methods for culturing adipose tissue explants in basement membrane matrix domes and imaging primary isolated adipocytes. Importantly, this approach can be integrated with existing protocols for the isolation of adipose tissue-resident adipocyte progenitor cells using fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). Together, these protocols provide researchers with tools to functionally study adipocytes, adipocyte progenitor cells, and whole adipose tissue from lean and obese, male and female mice.

Introduction

It is expected that the prevalence of adult obesity in the United States will reach 50% by 20301, making it imperative to better understand the cellular and physiological effects of obesity. Obesity is characterized by caloric imbalance resulting in the expansion of white adipose tissue due to increased storage of energy as fat. Adipose tissue expansion can occur both through the generation of new adipocytes (hyperplasia) or through an increase in the size of existing adipocytes (hypertrophy). Although both processes result in the expansion of adipose tissue, hypertrophic expansion coincides with reduced metabolic health and higher incidences of metabolic disorders2,3. A better understanding of the complexities of adipose tissue will provide insight into the molecular mechanisms regulating metabolic disorders and other obesity-related comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes and cancers.

Adipose tissue has long been appreciated for its role in energy storage and thermoregulation. More recently, however, adipose tissue has emerged as an important metabolic signaling tissue, responsible for the secretion of metabolites, lipids, and peptides4,5. These adipose tissue-derived molecules, termed adipokines, signal locally and systemically and can regulate energy homeostasis, immune function, vascular dynamics, and more5,6,7. Mature adipocytes make up approximately 50% of cells in adipose tissue and represent the large majority of adipose tissue volume8. Importantly, studies have found that adipocytes consist of many subpopulations9,10. As such, adipocyte progenitor cells generate distinct populations of mature adipocytes based on factors such as sex and adipose tissue depot. These mature adipocytes can be further modulated by changes in diet and obesity, creating subpopulations of adipocytes that are transcriptionally distinct and express different paracrine signatures9,11,12,13,14,15,16. Despite their complexity and physiologic importance, the ability to isolate and culture mature adipocytes remains a distinct barrier to studying these cells.

The currently available methods used to isolate mature adipocytes employ differentiation from adipocyte progenitor cells (APCs), fluorescent activated cell sorting, and centrifugation-based techniques, though all of these have their own drawbacks. In vitro or ex vivo differentiation of APCs into mature adipocytes is widely used to develop mature adipocytes. However, these artificially differentiated cells are multilocular, containing many small lipid droplets, rather than the unilocular phenotype of mature adipocytes in vivo, which contain one large lipid droplet17. Furthermore, studies have found that in vitro differentiated cells are transcriptionally distinct from isolated mature adipocytes found in vivo17. Importantly, in vitro differentiation is unable to capture the difference between lean and obese adipocytes. Fluorescent-activated cell sorting (FACS) is commonly used to isolate specific cell populations from tissue; however, mature adipocytes can easily burst under FACS conditions due to their large size and fragile membranes, making this an inefficient method for mature adipocyte isolation. Other existing protocols result in the accumulation of large quantities of free lipids, which can be toxic to mature adipocytes in culture over time.

Here, we describe a protocol for the isolation of murine mature adipocytes from white adipose tissue. This protocol was adapted from the protocol for mature adipocyte aggregate cultures originally established by Harms et al.17; however, the centrifugation-based approach described here uses common laboratory equipment and is capable of efficiently isolating adipocytes from small amounts (~0.5 g) of adipose tissue. This is an easily adaptable system, and modifications for isolating mature murine adipocytes from male and female mice, visceral and subcutaneous fat depots, and different diet conditions are included.

Protocol

All animal experiments described were approved by the University of Utah's Committee on the Use and Care of Animals. This protocol has been optimized for the isolation of mature adipocytes from C57BL/6 male and female mice aged 8-16 weeks, with body weights ranging from 20-45 g. Details of the reagents and equipment used in this study are provided in the Table of Materials.

1. Solution preparation

- Prepare collagenase buffer. Add 100 mg of collagenase powder, 1 mL of 1 M HEPES buffer, 500 µL of 100x P188, 50 µL of 1 M CaCl2, 0.05 g of BSA, and 48.45 mL of Medium 199. Sterile filter the solution, aliquot, and store at -20 °C.

- Make cell culture media. Combine 500 mL of DMEM, 50 mL of FBS, 5 mL of Penicillin-Streptomycin, and 5 mL of L-glutamine supplement.

2. Collection of white adipose tissue depots from mice

- Prepare a 1 x 10 cm plate with 200 µL of HBSS for each different depot and condition as appropriate and place it on ice.

- Retrieve the animals from the animal house and euthanize the mice in accordance with the guidelines of the Institution's Animal Care and Use Committee. Here, animals were euthanized by cervical dislocation under deep anesthesia.

- Weigh and record the weight of each mouse if appropriate.

- Sterilize the mouse by spraying 70% ethanol to coat the exterior.

- Harvest the appropriate fat pads from the mouse18,19.

NOTE: Take care to remove the lymph nodes from the subcutaneous depot before placing the tissue into the dish. - Weigh each fat and record the weight.

- Place the fat pad in the prepared 10 cm plate on ice.

3. Preparation of white adipose tissue explants

NOTE: This step is optional.

- At least 12 h before beginning dissection, thaw the basement membrane matrix (Matrigel) at 4 °C on ice and chill one box of sterile 200 µL pipette tips at 4 °C.

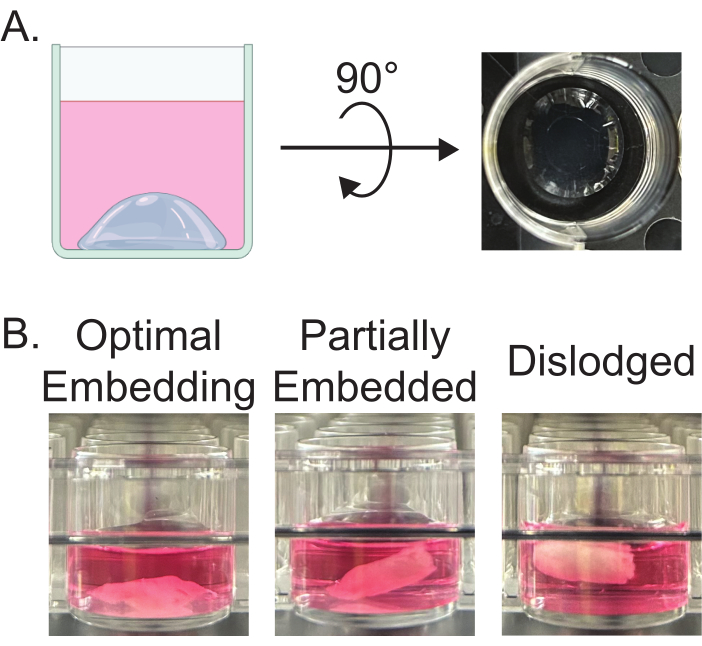

- Using chilled pipette tips, pipette 80 µL of basement membrane matrix into the center of each well of a 24-well culture plate to create a dome (Figure 1A). Place the plate in the incubator (37 °C, 5% CO2) for 30 min to partially solidify the matrix.

- Prepare tissue: Using sterile dissection scissors, weigh 0.1 g of tissue from each sample and place it in PBS on ice.

- With sterile forceps, embed pre-weighed tissue into the partially solidified matrix dome. Add 30 µL of basement membrane matrix on top of the embedded tissue. Return the plate to the incubator for 30 min to set the tissue in the basement membrane matrix.

NOTE: Embedding tissue in the basement membrane matrix is crucial to ensure that tissue remains in culture rather than floating. This preserves the health and quality of tissue (Figure 1B). - Add 1 mL of growth media (DMEM with 10% FBS) to each well and return to the incubator.

4. Collagenase treatment

- Calculate the amount of collagenase solution needed. See Table 1.

- Prepare collagenase solution with DNase. Add 0.00017 g of DNase per 1 mL of collagenase solution. Vortex to mix.

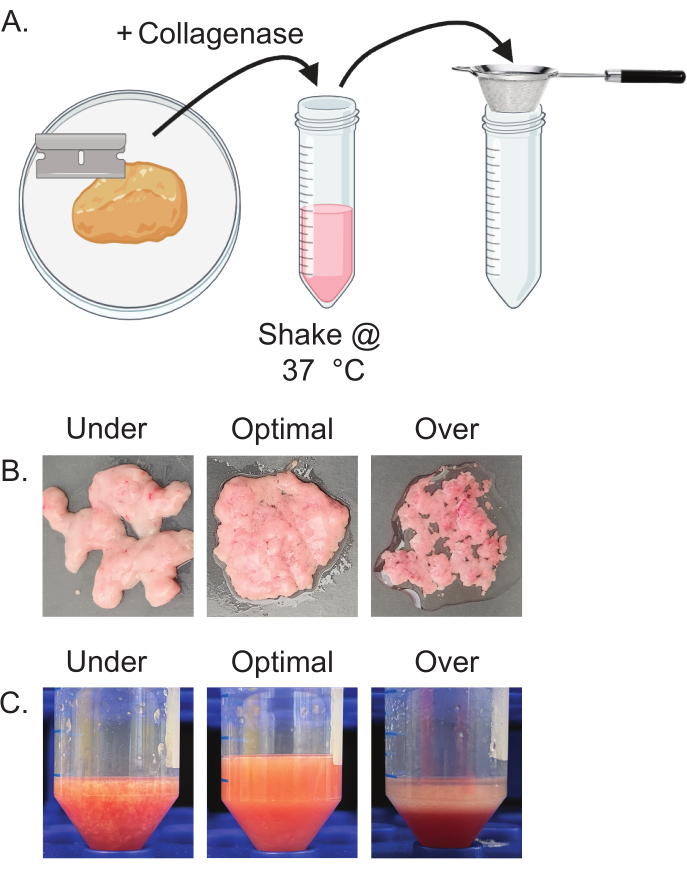

- Using a razor blade, mince the isolated adipose tissue until the tissue appears homogeneous (Figure 2A). Transfer minced tissue to a sterile 50 mL conical tube.

NOTE: Do not over-mince. Mincing is complete when tissue appears homogeneous and paste-like. Under-minced tissue appears chunky and heterogeneous, and over-minced tissue will result in the release of free lipids (Figure 2B). - Add prepared collagenase and DNase solution to the minced adipose tissue using volumes calculated in step 4.1. Vortex at maximum speed for 7-10 s to thoroughly combine. Place 50 mL conical tubes horizontally in a shaker set to 220 rpm, 37 °C.

- Incubate shaking for 10 min, then vortex for 5 s and check the samples. Fully digested samples will appear homogeneous with no visible clumps or tissue pieces. If samples are not fully digested, continue digestion in the shaker, checking every 2 min (Figure 2C).

NOTE: Do not over-digest. Excessive time in collagenase solution can result in the breakdown of adipocytes and the release of lipids. - Use a serological pipette to pass the digested tissue through a sieve into a new 50 mL conical. Add a volume of FBS equal to the volume of tissue + collagenase solution through the sieve into a conical to neutralize collagenase.

NOTE: A small amount of tissue will remain in the sieve after filtering.

5. Washing the tissue

NOTE: Complete all the following steps in a sterile tissue culture hood.

- Prepare 1 x 15 mL tube with 10 mL of warm culture media for each condition.

- Spin the tubes from step 4.6 at 300 x g for 3 min at the temperature specified in Table 1.

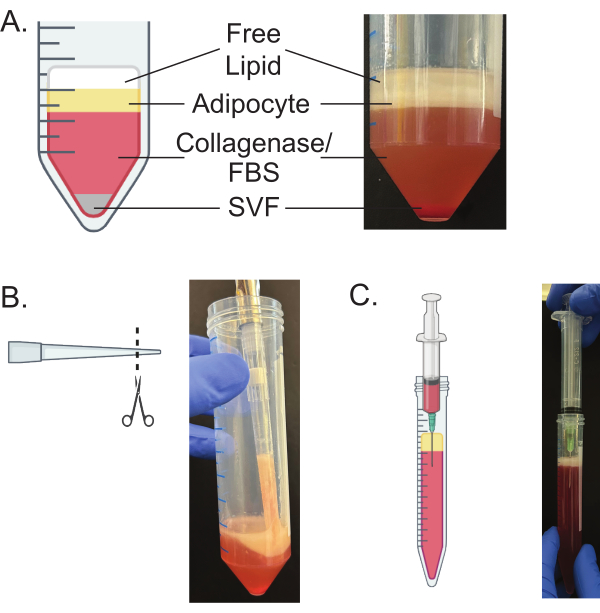

NOTE: The temperature for centrifugation needs to be modified based on the sex of the mice from which the adipose tissue was isolated; these temperatures are provided in Table 1. - Ensure that after spinning, the tissue separates into four layers (Figure 3A).

NOTE: The topmost layer is the free lipids, the second layer is the mature adipocyte layer, the third layer is the collagenase and FBS, and the fourth layer is the stromal vascular fraction (SVF) that pellets to the bottom20,21. - Carefully discard the top layer of free lipids with a 200 µL pipette.

- After removing the top layer, use a p1000 pipette with the bottom cut off to transfer the mature adipocytes to the prepared 15 mL tube with 10 mL of growth media (Figure 3B).

- Optional: To isolate the primary adipocyte progenitor cells (APCs), spin the tubes again at 300 x g for 10 min. Then proceed to the adipocyte progenitor cell isolation by Liu et al.22, Cho et al.23, or similar.

- Invert the 15 mL tubes with the mature adipocytes gently 3-5 times until the white layer has dispersed throughout the media.

- Let the tubes rest upright for 10 min at the temperature indicated in Table 1 to allow for separation of the adipocyte and media layers.

- After the 10 min rest, spin the tubes at 100 x g for 1 min at room temperature to further promote separation of layers. Following the spin, the samples will be separated again into four layers, as shown in Figure 3A.

- Remove and discard the top layer of free lipids with a pipette.

- Using a 21 G needle attached to a 5 mL syringe, slide the needle down the edge of the tube until the bottom of the needle is clear of the mature adipocyte layer (Figure 3C). Ensure that the top of the needle and bottom of the syringe do not disturb the mature adipocyte layer.

- Slowly pull up the syringe to remove the culture media and any cellular debris.

NOTE: As the media is removed, ensure that the needle tip is clear of the mature adipocyte layer. - Gently add 10 mL of culture media to each tube.

- Repeat steps 5.6-5.11. Do not add more culture media.

- Using gel-loading pipette tips, slide the pipette tip down the edge of the tube to remove the remaining media from below the mature adipocyte layer.

6. Packing

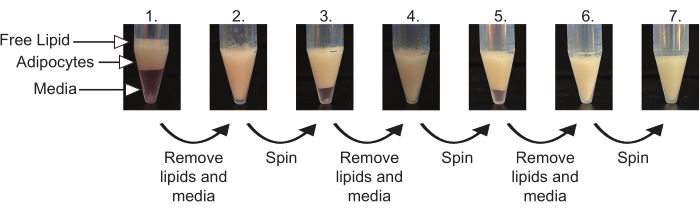

- Centrifuge cells at 100 x g for 1 min at the temperature indicated in Table 1. Remove free lipids (clear oil layer on top of cells) using a pipette. Remove the culture media below adipocytes using a gel loading tip. Take care to minimize disruption of the adipocyte layer (Figure 4).

- Repeat step 6.1 until all culture media and free lipids have been removed (typically 3-5 times). The cell pack should be white in color with no visible free lipids above cells or media below cells (Figure 4).

7. Plating and functional assays

- Plating the mature adipocytes for cell culture

- Remove the cell culture inserts from a tissue culture-treated 24-well plate and place them with the membrane side up on the surface of the hood.

- Fill alternating wells of the plate with 1 mL warm culture media.

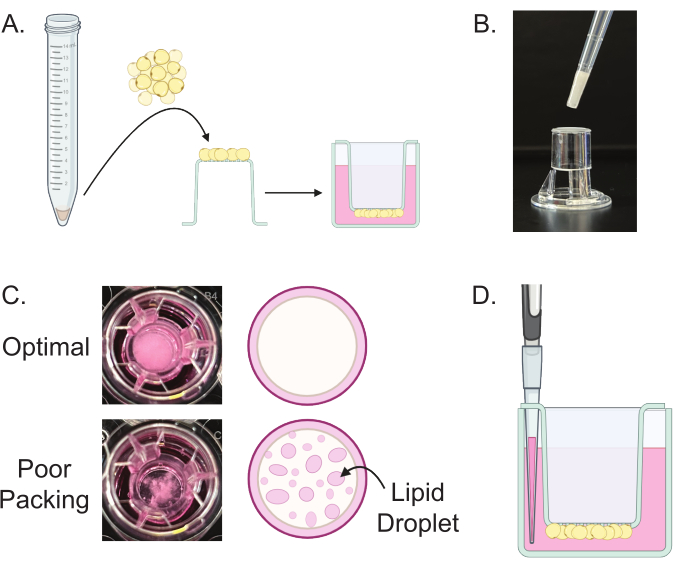

- Using a cut p200 pipette tip, place 30 µL of packed mature adipocytes from step 6.2 onto the top of a transwell insert (Figure 5A,B).

- Carefully pick up and invert the transwell insert and place it into a prefilled well in the 24-well plate (Figure 5A). Carefully place the plate into the incubator set at 37 °C with 5% CO2.

NOTE: Properly packed adipocytes should form an opaque layer with no visible clear free lipid droplets when viewed from above (Figure 5C). - Change the media on the mature adipocytes every 2-7 days for up to 14 days.

- To remove the media from the wells, hold the transwell in place, and use a p200 pipette to carefully remove the media through the small openings on the side of the transwell insert (Figure 5D).

- Once media has been removed, while still holding the transwell in place, very slowly add 1 mL of media to the side wall of the well.

NOTE: Take care to add and remove media very slowly. Adipocytes can easily become dislodged from the membrane if the media is changed quickly.

- Lipolysis assay

- Plate adipose tissue explants as described in step 3.4 or mature adipocytes as described in step 7.1.

NOTE: Cells or tissue must be cultured in phenol red-free media for at least 24 h before conducting lipolysis assay. - Solution preparation: Prepare a solution of 5% BSA in DMEM (no phenol red) by dissolving 5 g of BSA in 100 mL of DMEM. Invert gently to combine until BSA is fully dissolved.

- Prepare working solutions for control and stimulation media. For control media, combine 5% BSA DMEM media with the vehicle. For stimulation media, combine 5% BSA DMEM media with 5 µM of CL-316,243. Warm the control and stimulation media to 37 °C prior to use.

- Remove media from wells and wash with 1 mL warm DPBS. Fill wells with 500 µL per well of control or stimulation media. Incubate at 37 °C, 5% CO2.

- At 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, and 24 h after initiating the lipolysis assay, collect 100 µL of media from each well into a microcentrifuge tube and replace it with 100 µL of the appropriate control or stimulation media.

NOTE: Samples can be stored at -20 °C at this point. - Run Glycerol Colorimetric Assay using a commercially available free glycerol kit (see Table of Materials) or similar.

- Prepare reagents as directed in the kit.

- Thaw samples and mix gently by pipetting.

- Prepare a standard curve with a seven-point, 2-fold serial dilution using the glycerol standard solution.

- Transfer 25 µL of sample or standard to each well of a clear-bottom 96-well plate.

- Add 100 µL of free glycerol assay reagent to each well containing sample or standard solution.

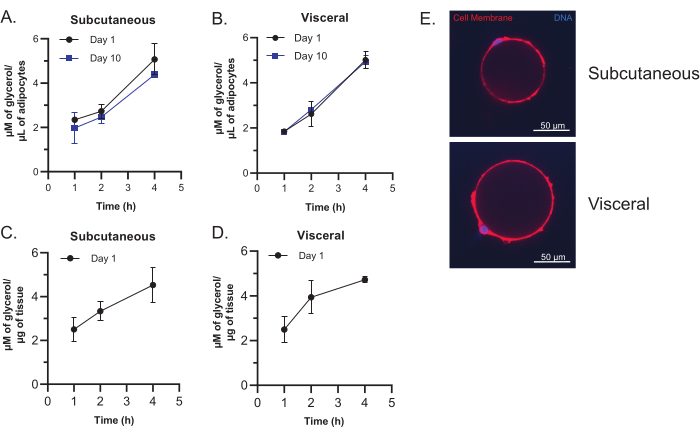

- Incubate for 15 min at room temperature, then read the absorbance at 540 nm (Figure 6A-D).

- Plate adipose tissue explants as described in step 3.4 or mature adipocytes as described in step 7.1.

- Imaging

- Prepare the imaging slides. To prepare slides, remove the backing paper layer from each imaging spacer and place it onto the slide. Two imaging spacers can be placed side-by-side on each slide.

- Using a cut 200 µL pipette tip, transfer 30 µL of packed adipocytes from step 6.2 into a microcentrifuge tube.

- Prepare the staining mix. Prepare 200 µL per sample of plasma membrane staining solution at 5 µg/mL and Hoechst at 4.5 µg/mL in PBS. Add stain mix to samples and gently shake.

- Stain samples for 30 min at room temperature. Protect the samples from light.

- After the staining is complete, wash the samples. Add 500 µL PBS to each sample and shake gently to combine. Let stand for 5 min. Spin at 100 x g for 1 min, then remove media from under the cells with a gel loading pipette tip.

- Prepare the slides. Remove the clear plastic film from the top side of the imaging spacers to expose the sticky layer.

- Add 500 µL of PBS to the tube of stained adipocytes and mix gently.

- Quickly, so as to not allow time for the mature adipocytes to rise to the surface, use a cut p200 pipette tip to place 35 µL of the adipocytes within the spacer on the imaging slide.

- Place a cover slip on the spacer.

- Immediately proceed to imaging (Figure 6C). A delay in imaging may result in bleeding of the membrane marker.

Representative Results

As shown in Figure 2, proper mincing (Figure 2B) and digestion (Figure 2C) are important for the isolation of intact mature adipocytes. Under-mincing and under-digestion can result in a low yield of mature adipocytes due to inadequate separation from the connective tissue. Visually, this can be observed with stringy tissue remaining after mincing and visible clumps in collagenase solution. Additionally, over-mincing and over-digesting also result in low yield due to the bursting of the mature adipocytes. Visually, this results in the loss of the white opaque layer and an accumulation of a large, clear, free lipid layer. Inappropriate levels of mincing or digestion will result in poor adipocyte isolation.

Proper preparation and digestion of adipose tissue will result in the separation of the tissue into four distinct layers, as seen in Figure 3. Some bursting of the adipocytes resulting in the release of free lipids is inevitable; however, proper mincing and digestion will ensure minimal adipocyte rupture. The remaining free lipid layer and media will be removed during the packing of the adipocytes (Figure 4). The proper packing of the adipocytes is essential for the efficient isolation of mature adipocytes. Any remaining free lipids or media will result in poor isolation and negatively impact downstream functional assays, such as plating, lipolysis, and cell imaging.

This protocol generates a clean preparation of mature adipocytes. Cell imaging and lipolysis assays can be performed to assess cellular function and demonstrate that the mature adipocytes retain function post-isolation and after culturing for up to two weeks. The lipolysis assay indicates that the mature adipocytes maintain the ability to respond to cellular signaling through the release of free glycerol upon stimulation of the β-3 adrenergic receptor (Figure 6A,B). This ability is retained even after 2 weeks in culture and is highly comparable to the lipolysis activity of adipose tissue explants cultured for 24 h (Figure 6C,D). Poor-quality adipocytes will show attenuated lipolysis. The cell imaging of isolated adipocytes shows round and intact unilocular mature adipocytes containing a single large lipid droplet. Poor-quality adipocyte isolations will show primarily large, extracellular oil droplets indicative of burst adipocytes.

Figure 1: Embedding of adipose tissue explants. (A) Image of partially-solidified basement membrane matrix dome prior to embedding the tissue. (B) Representative images of improper and proper tissue embedding. Improper embedding is visible as the tissue appears to float partially or completely above the dome. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Schema of proper mincing and digestion of adipose tissue. (A) Schematic representation of tissue mincing and digestion steps 4.2-4.6. (B) Representative images of under, optimal, and over-minced tissue. Under-minced tissue has large chunks that retain their original shape. Over-minced tissue results in a visible increase in the free lipids surrounding the tissue, which appear clear and oily. (C) Representative images of under, optimal, and over-digested tissue. Under-digested tissue contains chunks of whole tissue remaining in the solution. Over-digested tissue exhibits a large free lipid layer that quickly separates from the solution. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: Separation of layers of digested adipose tissue. (A) Schematic and representative image of the layers that are present following step 5.3. (B) Use of a cut pipette tip to remove the mature adipocyte layer from the 50 mL conical tube. (C) Proper technique and placement for the needle and syringe to remove the culture media from below the mature adipocyte layer. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: Sequential packing of mature adipocytes. Sequential images of packing the mature adipocytes. Layers of free lipids, adipocytes, and media are labeled. Following each spin, free lipids and media are removed. This is repeated until no media or free lipids separate from the adipocytes after a spin. The final image is representative of well-packed mature adipocytes. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5: Plating and culturing of mature adipocytes. (A) Schematic of the plating of mature adipocytes. Using a cut p200 pipette tip, packed adipocytes are placed onto the membrane of a cell culture insert. The insert is then inverted into pre-filled wells of culture media. (B) A representative image of plating mature adipocytes depicting cut pipette tip depositing adipocytes on transwell insert. (C) Schematics and representative images of properly packed and poorly packed adipocytes plated with transwells, as seen from above the wells. Properly packed adipocytes appear white and opaque, while poorly packed adipocytes result in the formation of clear lipid droplets. (D) Schematic of the technique used to change culture media. A p200 pipette tip is used to carefully remove the media through the openings in the side wall of the transwell insert. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 6: Imaging of mature adipocytes and lipolysis assay. (A,B) Glycerol release from subcutaneous (A) and visceral (B) mature adipocytes. Adipocytes were isolated from 16-week-old C57BL/6 male mice fed a normal chow diet. 30 µL of adipocytes were plated as described in step 7.1 and cultured for 1 or 10 days. Adipocytes were treated with 5 µM of CL-316,243 for 1 h, 2 h, and 4 h, and supernatants were collected and analyzed for free glycerol. (C,D) Glycerol release from subcutaneous (C) and visceral (D) adipose tissue explants. Adipose tissue was isolated from 18-week-old C57BL/6 female mice fed a normal chow diet. 0.1 g of adipose tissue explants were plated as described in steps 3.1-3.4 and cultured for 24 h. Adipocytes were treated with 5 µM of CL-316,243 for 1 h, 2 h, and 4 h, and supernatants were collected and analyzed for free glycerol. N = 3 technical replicates for A-D. All data are mean ± standard deviation. (E) Representative images of isolated subcutaneous and visceral mature adipocytes. Adipocytes were isolated from 16-week-old C57BL/6J male mice fed a normal chow diet. Adipocytes were stained with plasma membrane stain (red) and Hoechst nuclei stain (blue). Scale bars: 50 µm; magnification: 60x. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| Sex | Diet | Depot | Mincing difficulty | Collagenase: Tissue ratio | Suggested digestion time (min) | Spin temp. | Wash temp. |

| Female | Normal chow | Subcutaneous | Hard | 2:1 | 12 | RT | 37 °C |

| Visceral | Medium | 1:1 | 8 | RT | 37 °C | ||

| High fat diet | Subcutaneous | Easy | 1:1 | 8 | RT | 37 °C | |

| Visceral | Easy | 1:1 | 8 | RT | 37 °C | ||

| Male | Normal chow | Subcutaneous | Hard | 2:1 | 14 | 4 °C | RT |

| Visceral | Medium | 1:1 | 10 | 4 °C | RT | ||

| High fat diet | Subcutaneous | Easy | 1:1 | 10 | 4 °C | RT | |

| Visceral | Easy | 1:1 | 10 | 4 °C | RT |

Table 1: Sex, depot, and diet-specific modifications. The mincing difficulty of each tissue, described as "Easy", "Medium", or "Hard" in relation to other depots. Note that actual mincing time will vary depending on the researcher and tissue. Collagenase: Tissue ratio listed as volume (mL) of collagenase + DNase solution prepared in step 4.1 to the weight of tissue (g). Digestion time is an approximate estimate, but actual digestion time will vary according to mincing and tissue. Researchers should assess digestion as described in the protocol. Spin temperature and wash temperature differ between male and female mice. RT denotes room temperature.

Discussion

Primary adipocytes are notoriously difficult to isolate and culture because they rupture easily, and their large size precludes the use of common primary cell isolation tools such as flow cytometry. The protocol described here yields clean and functional mature adipocytes, which can be used for a variety of downstream applications. Importantly, this protocol allows for the separation of the mature adipocytes from other cellular debris and the free lipid layer, allowing effective imaging, culturing, and lipolysis assays. The protocol can readily be combined with published protocols22,23 for the isolation of the stromal vascular fraction and APCs. This protocol also details a procedure for the preparation and culturing of whole-tissue explants from adipose tissue, which can be used for downstream applications such as lipolysis assays and the collection of secreted factors from whole adipose tissue.

Critical aspects include proper mincing, digestion, and removal of the free lipid layer. To ensure proper mincing, it is important to closely monitor the tissue's visual appearance throughout the process. The time and effort needed to achieve an optimal mince of the tissue will vary depending on the adipose tissue depot, dietary interventions (such as a high-fat diet), and the researcher. Other tools for mincing, such as scissors, can be incorporated if necessary, but this has not been explored here. Of note, over-mincing should be avoided as it will rupture adipocytes, which not only decreases the immediate yield but also decreases total yield and adipocyte quality due to the deleterious effect the free lipid layer has on the remaining adipocytes. Proper digestion, similar to a proper mince, will depend on the adipose tissue depot, dietary interventions, age of mice, etc. The addition of DNase to the collagenase helps to prevent the aggregation of the adipocytes during digestion, which can result from cellular debris. The digestion time for tissues is, therefore, highly variable. The provided estimates for digestion times serve as a guide, which can be found in Table 1. However, the best way to ensure the tissues are properly digested is to visually inspect the tissue throughout the process and as described in the protocol. The different centrifugation and wash temperatures detailed in Table 1, suggested based on sex, are essential for the proper separation of the mature adipocytes from both the free lipid layer as well as the other cellular debris and SVF; use of alternate temperatures may result in the loss of the mature adipocytes due to aggregation and adipocyte bursting.

The removal of the free lipid layer at every step is of critical importance, and failure to do so will present downstream complications for plating, imaging, and the lipolysis assay. Further, the sustained presence of the free lipid layer throughout the procedure will result in additional adipocyte death due to lipotoxicity, dramatically impacting overall yield and quality. While maximizing the efficiency of the mature adipocyte isolation is generally desired, removing the free lipid layer, even at the expense of some of the mature adipocytes, will result in an overall increase in mature adipocyte yield at the end of the protocol.

Limitations of the procedure include the number of samples. Due to the rigor and time consumed by the removal of media and free lipid layer, the procedure is generally limited to six samples at a time. Processing significantly more samples will result in primary adipocytes being exposed to free lipids for too long and decrease the overall yield. However, additional personnel may allow for an increase in the number of samples. The time from mincing to functional assay is critical as excessive delays in the removal of media and free lipid layer result in additional mature adipocyte bursting. The protocol is further limited in the ability to separate sub-populations of mature adipocytes.

Current methods to study mature adipocytes primarily rely on the isolation of APCs and the subsequent ex vivo differentiation of these cells. Additional methods, including organ-on-a-chip model and trans well co-cultures, have begun to be developed18,24. However, these ex vivo differentiated adipocytes have been shown to be transcriptionally and morphologically distinct from the mature adipocytes in the adipose tissue17. Morphologically, ex vivo differentiated adipocytes are multilocular, while in vivo isolated adipocytes are unilocular. This protocol was modified and optimized from previous reports17,25 to successfully isolate and culture mature adipocytes from as little as 0.5 g of adipose tissue compared to other protocols that require at least 5 g of adipose tissue25 . Finally, this study aimed to visually illustrate the successful completion of key steps in the protocol in lieu of concrete times, centrifugation temperatures, and collagenase amounts, though guidelines are included in Table 1. These parameters need to be adjusted according to factors such as the adipose tissue depot, the sex, and the adiposity of the animal, all of which can impact the efficiency of the digestion and clean separation of mature adipocytes in this protocol.

In total, the procedure takes 3-4 h, depending on the number of mice pooled and the number of individual adipose tissue samples. It is anticipated that the ability to culture and assess the functional role of mature adipocytes will enable many downstream applications for the study of adipocyte biology itself (e.g., metabolism, nutrient utilization, and tracing) and the interaction of adipocytes with other cell types, such as APCs, cancer cells, and cells of the immune system.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge grant support from 5 For The Fight and Huntsman Cancer Institute (KIH), the V Foundation for Cancer Research (KIH), and DK133455 (KIH). Schematics of the protocol created with Biorender. Additionally, the authors would like to thank Stephanie Giagnocavo and the Cell Imaging Core at the University of Utah for imaging help, and Mark Lee for feedback on the manuscript.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 100x Poloxamer 188 solution | Sigma | P5556-100mL | |

| 15 mL conical | Cellstar | 188261 | |

| 21 G Needle | BD | 305165 | |

| 5 mL Syringe | BD | 309646 | |

| 50 mL Conical | Cellstar | 227261 | |

| 6.5 mm Transwell with 0.4 µm Pore Polycarbonate Membrane Insert | Corning | 3413 | |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Sigma-Aldrich | A7906-100G | |

| CaCl2 | Sigma | C1016-500gm | |

| CellMask Plasma Membrane Stains | Thermo Fisher Scientific | C10045 | |

| CL 316243 disodium salt | Tocris | 1499 | |

| Collagenase Powder | Sigma | C6885 | |

| DMEM | Gibco | 11995-040 | |

| DMEM no pheonol Red | Gibco | A14430-01 | |

| DNase I | Sigma-Aldrich | 10104159001 | |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Gibco | A56708-01 | |

| Fisherbrand Tissue Path Superfrost Plus Gold Slides | Fisher scientific | 1518848 | |

| Gel Loading Pipet Tip | Fisher scientific | 02-707-181 | |

| GlutaMAX Supplement | Gibco | 35050061 | |

| Glycerol Assay Kit | Abcam | AB133130 | |

| Hanks' Balanced Salt Solution (HBSS) | Gibco | 14025-092 | |

| HEPES Buffer | Sigma | 83264-100ml-F | |

| Heraeus Megafuge 16R Centrifuge | Thermo Scientific | 75004271 | |

| Hoechst 33342 Solution | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 62249 | |

| Incubating Mini Shaker | VWR | 12620-942 | |

| Medium 199 | Sigma-Aldrich | M4530 | |

| Microscope Cover Glasses | VWR | 16004-302 | |

| PBS | Gibco | 10010023 | |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | Gibco | 15140-122 | |

| SecureSeal Imaging Spacers | Grace Biolabs | 654006 | |

| Seive (SteeL Fine Mesh Cocktail Strainer) | OXO | 3112000 | https://www.oxo.com/steel-fine-mesh-cocktail-strainer-660.html |

References

- Ward, Z. J. et al. Projected U.S. state-level prevalence of adult obesity and severe obesity. N Engl J Med. 381 (25), 2440-2450 (2019).

- Vishvanath, L. Gupta, R. K. Contribution of adipogenesis to healthy adipose tissue expansion in obesity. J Clin Invest. 129 (10), 4022-4031 (2019).

- Longo, M. et al. Adipose tissue dysfunction as determinant of obesity-associated metabolic complications. Int J Mol Sci. 20 (9), 2358 (2019).

- Funcke, J. B. Scherer, P. E. Beyond adiponectin and leptin: Adipose tissue-derived mediators of inter-organ communication. J Lipid Res. 60 (10), 1648-1684 (2019).

- Johnston, E. K. Abbott, R. D. Adipose tissue paracrine-, autocrine-, and matrix-dependent signaling during the development and progression of obesity. Cells. 12 (3), 407 (2023).

- Koenen, M., Hill, M. A., Cohen, P., Sowers, J. R. Obesity, adipose tissue and vascular dysfunction. Circ Res. 128 (7), 951-968 (2021).

- Liu, P. et al. Transcriptomic and lipidomic profiling of subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissues in 15 vertebrates. Sci Data. 10 (1), 453 (2023).

- Wu, Y., Li, X., Li, Q., Cheng, C., Zheng, L. Adipose tissue-to-breast cancer crosstalk: Comprehensive insights. Biochim Biophys Acta Rev Cancer. 1877 (5), 188800 (2022).

- Emont, M. P. et al. A single-cell atlas of human and mouse white adipose tissue. Nature. 603 (7903), 926-933 (2022).

- Nahmgoong, H. et al. Distinct properties of adipose stem cell subpopulations determine fat depot-specific characteristics. Cell Metab. 34 (3), 458-472 e456 (2022).

- Hildreth, A. D. et al. Single-cell sequencing of human white adipose tissue identifies new cell states in health and obesity. Nat Immunol. 22 (5), 639-653 (2021).

- Maniyadath, B., Zhang, Q., Gupta, R. K., Mandrup, S. Adipose tissue at single-cell resolution. Cell Metab. 35 (3), 386-413 (2023).

- Gao, Y. et al. Adipocytes promote breast tumorigenesis through taz-dependent secretion of resistin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 117 (52), 33295-33304 (2020).

- Cornide-Petronio, M. E., Jimenez-Castro, M. B., Gracia-Sancho, J., Peralta, C. New insights into the liver-visceral adipose axis during hepatic resection and liver transplantation. Cells. 8 (9), 1100 (2019).

- Verma, S. et al. Zinc-alpha-2-glycoprotein secreted by triple-negative breast cancer promotes peritumoral fibrosis. Cancer Res Commun. 4 (7), 1655-1666 (2024).

- Min, S. Y. et al. Diverse repertoire of human adipocyte subtypes develops from transcriptionally distinct mesenchymal progenitor cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 116 (36), 17970-17979 (2019).

- Harms, M. J. et al. Mature human white adipocytes cultured under membranes maintain identity, function, and can transdifferentiate into brown-like adipocytes. Cell Rep. 27 (1), 213-225 e215 (2019).

- Chaurasiya, V. et al. Human visceral adipose tissue microvascular endothelial cell isolation and establishment of co-culture with white adipocytes to analyze cell-cell communication. Exp Cell Res. 433 (2), 113819 (2023).

- Galmozzi, A., Kok, B. P., Saez, E. Isolation and differentiation of primary white and brown pre-adipocytes from newborn mice. J Vis Exp. 167, e62005 (2021).

- Farrar, J. S. Martin, R. K. Isolation of the stromal vascular fraction from adipose tissue and subsequent differentiation into white or beige adipocytes. Methods Mol Biol. 2455, 103-115 (2022).

- You, X., Gao, J., Yao, Y. Advanced methods to mechanically isolate stromal vascular fraction: A concise review. Regen Ther. 27, 120-125 (2024).

- Liu, Q. et al. Progenitor cell isolation from mouse epididymal adipose tissue and sequencing library construction. STAR Protoc. 4 (4), 102703 (2023).

- Cho, D. S. Doles, J. D. Preparation of adipose progenitor cells from mouse epididymal adipose tissues. J Vis Exp. 162, e61694 (2020).

- Lauschke, V. M. Hagberg, C. E. Next-generation human adipose tissue culture methods. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 80, 102057 (2023).

- Alexandersson, I., Harms, M. J., Boucher, J. Isolation and culture of human mature adipocytes using membrane mature adipocyte aggregate cultures (MAAC). J Vis Exp. 156, e60485 (2020).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionExplore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

ABOUT JoVE

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved