Implementation of Portable Emissions Measurement Systems (PEMS) for the Real-driving Emissions (RDE) Regulation in Europe

In This Article

Summary

The European Commission has developed a Real-Driving Emissions (RDE) test procedure to verify pollutant emissions during real-world vehicle operation using the Portable Emissions Measurement Systems (PEMS). This paper presents the experimental procedures required by the newly-adopted RDE test.

Abstract

Vehicles are tested in controlled and relatively narrow laboratory conditions to determine their official emission values and reference fuel consumption. However, on the road, ambient and driving conditions can vary over a wide range, sometimes causing emissions to be higher than those measured in the laboratory. For this reason, the European Commission has developed a complementary Real-Driving Emissions (RDE) test procedure using the Portable Emissions Measurement Systems (PEMS) to verify gaseous pollutant and particle number emissions during a wide range of normal operating conditions on the road. This paper presents the newly-adopted RDE test procedure, differentiating six steps: 1) vehicle selection, 2) vehicle preparation, 3) trip design, 4) trip execution, 5) trip verification, and 6) calculation of emissions. Of these steps, vehicle preparation and trip execution are described in greater detail. Examples of trip verification and the calculations of emissions are given.

Introduction

Vehicles are tested in controlled laboratory conditions to determine their official emission values and fuel consumption (e.g., United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Regulation 83)1. For light-duty vehicles, Regulation 715/20072 defines the Euro 5 and 6 emission limits, to which vehicles in categories M1, M2 (passenger cars), N1, and N2 (vehicles for the carriage of goods) must comply. Compliance is verified by the so-called "Type I" test that measures tailpipe emissions after a cold start during a standardized test in the laboratory1. Although laboratory testing ensures reproducibility and comparability of results, it covers only a small range of the ambient, driving, and engine operating conditions that typically occur on the road. As a matter of fact, official laboratory test results reflect less and less the actual fuel consumption experienced by drivers on the road3. In addition, on-road vehicle emissions, specifically the NOX emissions of diesel cars, are also higher than the type-approval values4-5. Regulation 715/20072 contains provisions to ensure that the emission limits are respected under normal vehicle operation and use. Various new regulatory components are in the pipeline in order to reduce observed discrepancies, such as the World Harmonized Light-Duty Procedure (WLTP), mainly for CO2 and fuel consumption, and the Real-Driving Emissions (RDE) test procedure, mainly for pollutants.

Admittedly, the most important component of the new regulatory package for conventional pollutants is that compliance with the emission limits needs to be demonstrated over real-world vehicle operation following the RDE procedure. The new procedure will complement the measurement of emissions on the chassis dynamometers, so that a thorough control of regulated pollutants is achieved both in the laboratory and on the road. The RDE is based upon on-road emissions testing with the Portable Emissions Measurement Systems (PEMS). PEMS are not new, especially for heavy-duty vehicle testing. The United States Environmental Protection Agency (US-EPA) has added to the laboratory certification tests additional emissions requirements with the Not-To-Exceed (NTE) concept based on vehicle testing with PEMS. In Europe, PEMS-based In-Service Conformity (ISC) provisions for the EURO VI standards are applicable for EURO V engines6,7. PEMS measure emissions in the engine exhaust with a measurement performance (e.g., linearity, accuracy) that is comparable to that of laboratory-grade equipment8. The newest generation of PEMS weigh 30 kg, are compact, and can be easily installed in small passenger cars, thus having a minor impact on the vehicle.

To cope with the real-world variability of testing conditions, specific testing and data evaluation procedures must be implemented. Testing may occur under a wide range of altitude, temperature, and driving conditions. However, requirements concerning (i) trip composition (e.g., roughly equal shares of urban, rural, and motorway driving) and (ii) driving dynamics (e.g., the permissible range of accelerations) aim to ensure that vehicles are tested in a fair, representative, and reliable manner. Still, due to a number of factors (e.g., traffic, driver, and wind), any on-road test remains, to some extent, random and non-reproducible. Thus, the main challenge was the development of a data evaluation method that assesses ex post the normality of test conditions to enable a reliable assessment of vehicle emissions. To this end, two methods were adopted within the RDE: the moving averaging windows (MAW) and the power binning method. The MAW method divides the test into sub-sections (windows) and uses the distance-specific average carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions of each window to assess the normality of operating conditions. The power binning method categorizes the instantaneous on-road emissions into power bins based on the corresponding power at the wheels. The normality of the resulting power distribution is established through a comparison with a standardized wheel-power frequency distribution. Both methods include criteria to ensure that a realized test covers the range of driving dynamicity permitted by the RDE test procedure9-10. The two methods typically give results within 10%; however, differences on the order of 50% have been reported11,12. An in-depth assessment of the two data evaluation methods is still missing. The European Commission acknowledges this shortcoming in Recital 14 of the RDE Regulation13,14 and foresees a review of these two methods in the near future with the objective of retaining them or developing a unified method for the evaluation of gaseous pollutants and particle number emissions.

Until now, two RDE packages have been adopted by the Technical Committee on Motor Vehicles (TCMV) of the EU Member States and became law after their publication in the Official Journal of the European Union13-15. The first RDE package covered the boundary conditions, the actual test procedure, the PEMS specifications, and the data evaluation methods (MAW and/or power binning), but not emission limits (the package was voted on by the TCMV on the 18th of May 2015). The second RDE package added the not-to-exceed (NTE) emission limits applicable to RDE testing. In addition, complementary boundary conditions were introduced to check the excess or absence of driving dynamics. The emissions of each valid individual RDE test must be below the respective NTE emission limit, referred to in the regulation as conformity factors. Currently, only NOx emissions are covered. Binding conformity factors will be introduced in two steps: a factor 2.1 of the Euro 6 NOx limit (80 mg/km) will be applicable from 2017-2019 for new type approvals and all new car registrations. The conformity factor will subsequently be lowered to 1.5 in 2020-2021. The final Euro 6 conformity factor of 1.5 provides an allowance of 0.5 (i.e., 50%) for the additional measurement uncertainty of PEMS compared to laboratory equipment and the test-to-test emissions variability within the possible ranges of testing conditions (e.g., temperature, dynamics, and altitude). Regarding CO, although binding conformity factors are currently not discussed, on-road CO emissions have to be measured and recorded to obtain type approval. The second package was voted on by the TCMV on the 28th of October 2015.

The kick-off meeting of two additional packages was held on the 25th of January 2016. The third RDE package will address particle number PEMS testing, cold start emissions, and the testing of hybrid vehicles. Measuring particle number emissions on-board vehicles is challenging, as no verified technique has yet been established. New concepts and approaches were developed in the period between 2013 and 2014, including electrical detection of aerosol in real-time combined with constant flow sampling16. This package is to be voted on in the second half of 2016. The fourth RDE package will deal with the definition of requirements for in-service conformity and market surveillance testing. Completion of this package is foreseen by early 2017. The RDE Regulations 2016/42713 and 2016/64614 are currently integrated together with the Worldwide Harmonized Light-duty Vehicles Test Procedure (WLTP) into a larger EU type approval regulation that will supplement Regulation 715/20072.

The objective of this paper is to present the experimental procedures required by the newly-adopted RDE regulation. The RDE test procedure defines the boundaries of permissible test conditions, the protocol for testing vehicles, the requirements for instruments, and the evaluation methods to be applied for analyzing vehicle operation and the related pollutant emissions (Table 1). The procedure can be summarized in six steps: 1) vehicle selection, 2) vehicle preparation, 3) trip design, 4) trip execution, 5) trip verification, and 6) calculation of emissions. If any of the requirements in any of these six steps is not met, the test is considered failed. For a more detailed description of the RDE test procedure, the reader can refer to the regulation itself13-14.

| Annex IIIA of EC Regulation 692/2008 |

| 1. Introduction, definitions and abbreviations |

| 2. General requirements on conformity factors |

| 3. RDE test to be performed |

| 4. General requirements |

| 5. Boundary conditions |

| 6. Trip requirements |

| 7. Operational requirements |

| 8. Lubricating oil, fuel and reagent |

| 9. Emissions and trip evaluation |

| Appendices |

| Appendix 1:Test procedure for vehicle emissions testing with a PEMS |

| Appendix 2: Specifications and calibration of PEMS components and signals |

| Appendix 3: Validation of PEMS and non-traceable exhaust mass flow rate |

| Appendix 4: Determination of emissions |

| Appendix 5: Verification of trip dynamic conditions with method 1 (Moving Averaging Window) |

| Appendix 6: Verification of trip dynamic conditions with method 2 (Power Binning) |

| Appendix 7: Selection of vehicles for PEMS testing at initial type approval |

| Appendix 7a: Verification of overall trip dynamics |

| Appendix 7b: Procedure to determine the cumulative positive elevation gain of a trip |

| Appendix 8: Data exchange and reporting requirements |

| Appendix 9: Manufacturer's certificate of compliance |

Table 1: Structure of the RDE regulation. The regulation is considered to be ANNEX IIIA of Commission Regulation 692/200810. All parts and appendices are described in Commission Regulation 2016/427 (the first package)8. Appendices 7a and 7b, as well as the conformity factors, are described in Commission Regulation 2016/646 (the second package)9.

Protocol

1. Select the Vehicle

- For type approval purposes, choose a representative vehicle from a "PEMS test family." Families are considered to be vehicles with the same technical characteristics (i.e., propulsion type, fuel, combustion process, number of cylinders, engine volume, method of engine fueling, cooling system, after-treatment devices, and exhaust gas recirculation). For details, see Chapter 4 and Appendix 713.

- For any other purpose (e.g., comparison of laboratory versus on-road emissions), choose a vehicle that suits the experimental objectives.

2. Prepare the Vehicle

- Prepare the PEMS.

NOTE: See Appendix 1 of the Regulation8 for the PEMS equipment.- Use (at least) CO and NOx analyzers to determine the concentration of pollutants in the exhaust gas. Use a CO2 analyzer to determine the driving severity of the test (aggressiveness), during the verification and calculation steps.

- Use one or multiple instruments or sensors, such as an exhaust mass flow meter (EFM), to determine the exhaust mass flow.

- Use a global positioning system (GPS) to determine the position, altitude, and speed of the vehicle.

- If applicable, use sensors and other appliances that are not part of the vehicle (e.g., a weather station) to measure factors such as ambient temperature, relative humidity, air pressure, or vehicle speed.

- Use an energy source independent of the vehicle to power the PEMS. For passenger cars, 12 V or 24 V batteries are typically used.

- Optionally, use other auxiliary equipment, like battery chargers, a personal computer to remotely check the PEMS status, straps for installation of the PEMS inside of the car, or metal platform for installation on the tow bar outside of the car.

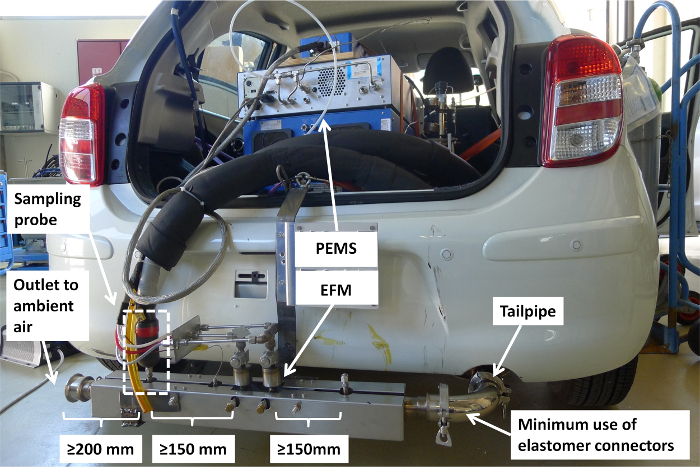

- Install the PEMS.

- Install the PEMS main and control units outside of the vehicle (e.g., on a tow bar by means of a dedicated platform) or in the boot/trunk (Figure 1). If the PEMS is installed in the cabin, fix it well using straps and vent excess gases outside the car, such as by using polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) tubes.

- Install at least CO2, CO, and NOx analyzers (and upon approval of the third RDE package, a particle number analyzer) with their heated sampling lines. Follow the instructions of the PEMS manufacturer and the local health and safety regulations.

- When the PEMS is not provided with its own batteries, mount a 12 V battery in the vehicle cabin, for instance, behind the co-driver's seat. Fix it well with straps.

- Using magnets, attach the weather station and GPS directly onto the vehicle chassis (e.g., on the roof of the vehicle). Connect the GPS signal cables to the PEMS main unit signal input port.

- Whenever an EFM is used, ensure that the measurement range of the EFM matches the exhaust mass flow rates expected during the test. Consult the manufacturer's specification sheet for the EFM. An example is given in Table 2.

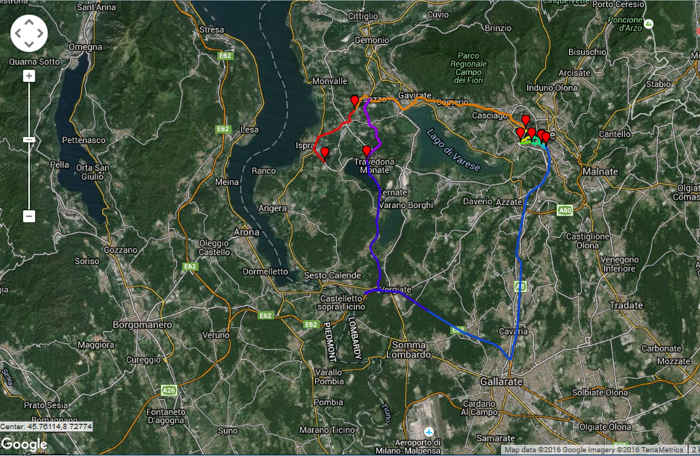

- Adapt the vehicle tailpipe to the EFM using hose clamps and flexible connectors or welding metal tubes. Use connectors that are thermally stable at the exhaust gas temperatures expected during the test in order to avoid the generation of particles. Avoid decreasing the inner diameter of the tailpipe using smaller tubes or decreasing the cross-section by adding many sampling probes at the same position.

- If in doubt, check that the installation and operation of the PEMS does not unduly increase the static pressure at the exhaust outlet. Measure the pressure with a pressure sensor (accuracy better than 0.1 kPa) in the exhaust outlet or in an extension with the same diameter, as closely as possible to the end of the pipe.

NOTE: If no pressure limits are given by the vehicle manufacturer, the addition of PEMS or any probes should not cause the static pressure at the exhaust outlets on the vehicle to differ by more than ± 0.75 kPa at 50 km/hr or more than ± 1.25 kPa at 120 km/hr from the static pressures recorded when nothing is connected to the vehicle exhaust outlets.

- If in doubt, check that the installation and operation of the PEMS does not unduly increase the static pressure at the exhaust outlet. Measure the pressure with a pressure sensor (accuracy better than 0.1 kPa) in the exhaust outlet or in an extension with the same diameter, as closely as possible to the end of the pipe.

- Fit the sampling probe(s) at least 200 mm upstream of the exit point of the exhaust outlet in order to minimize the influence of ambient air downstream of the sampling point (Figure 2). If an EFM is used, install the sampling probes downstream of the EFM, respecting a distance of at least 150 mm to the flow sensing element (Figure 2). The probes should have an appropriate length that permits sampling from the centerline. Probes with lengths equal to the inner diameter of the tailpipe can also be used if they have multiple holes along their lengths.

- Ensure that the maximum payload is respected (i.e., <90%). The PEMS plus a co-driver are around 150 kg, so the maximum load of the car is not reached. Add extra weights if the 90% limit must be reached.

- After the installing the PEMS, perform a leak check by following the instructions of the PEMS manufacturer. Block the probe tip with a soft plastic cap, turn the PEMS sample pumps on to draw a vacuum, and then shut them off. The pumps may be controlled by connecting the PEMS to a PC via an Ethernet cable. If this is not possible (e.g., the probe is installed in the exhaust stack), then perform the leak check from the sample inlet of the analyzer.

NOTE: The PEMS software communicates with the main unit and controls the pumps once the leak check procedure has begun. Monitor the vacuum pressure. The pass/fail pressure limit loss is specified by the PEMS manufacturers.

| Flow Tube Outer Diameter | ||||||||

| in | 1 | 1.5 | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

| mm | 25 | 38 | 51 | 64 | 76 | 102 | 127 | 152 |

| Flow Tube Length (length including extension) | ||||||||

| in | 20(26) | 20(26) | 20(26) | 25(32.5) | 25(34) | 25(37) | 30(45) | 36(54) |

| mm | 508(660) | 508(660) | 508(660) | 635(825) | 635(864) | 635(940) | 762(1,143) | 914(1,372) |

| Flow Rate at 100 °C (kg/hr) | ||||||||

| Min Flow | 6.9 | 10.9 | 15.8 | 18.9 | 22.5 | 30.7 | 38.6 | 46.2 |

| Max Flow | 85 | 276 | 535 | 890 | 1,250 | 2,080 | 3,115 | 4,005 |

| Flow Rate at 400 °C (kg/hr) | ||||||||

| Min Flow | 10.4 | 16.4 | 23.9 | 28.4 | 34 | 46.3 | 58.2 | 69.6 |

| Max Flow | 64 | 208 | 402 | 670 | 930 | 1,550 | 2,345 | 3,015 |

Table 2: Example of typical flow meter characteristics. For each flow meter, the dimensions and the maximum flow rates at different exhaust gas temperatures are given. The data comes from Sensors' High Speed Exhaust Flow Meter.

Figure 1: PEMS from different manufacturers. In these examples, the PEMS are installed outside of the vehicle on a support or on the tow bar. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: PEMS installation. The gas analyzers are located inside the vehicle. The minimum required distances before and after the EFM are also given in the figure. Note that no elastomer connectors were used in this setup. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

- Validate the PEMS installation.

NOTE: This sub-step is optional. However, it is recommended to validate the installed PEMS once for each PEMS-vehicle combination by running a test on a chassis dynamometer over a cycle similar to the one used for type approval, either before or after the on-road test.- Put the vehicle with the PEMS on a chassis dynamometer. Prepare the PEMS as in step 4 (see below) for conducting a trip.

- Drive a type approval test over a World Harmonized Light-vehicles Test Cycle (WLTC), following as far as feasible the requirements of the in-force laboratory regulation (see Appendix 3)13.

- Measure the pollutant emissions with the PEMS, in parallel with the laboratory equipment used for the type approval of vehicles.

- Calculate the PEMS emissions per second (as in step 4). Sum the calculated real-time emissions to get the total mass of pollutant emissions (g) and then divide it by the test distance (km) obtained from the chassis dynamometer.

- Compare the PEMS total distance-specific mass of pollutants (g/km) with the reference laboratory system calculated according to the regulation. The difference has to fulfil specific requirements for each pollutant (e.g., for NOx, ± 15 mg/km or 15% of the laboratory reference, whichever is larger).

3. Design the Trip

- Design the trip based on street maps. Have the executed trip fulfill the requirements specified in Tables 3 and 4.

- Ensure that the trip starts with an urban (U) part (speed ≤60 km/hr), continues with a rural (R) part, and ends with a motorway (M) part (speed >90 km/hr).

- Ensure that the shares of urban, rural, and motorway driving are equal. For the purpose of trip design, the definition of urban, rural, and motorway operation is defined on the basis of the instantaneous vehicle speed and takes into account the topography of the testing location.

During the definition of the motorway trip portion, pay attention to the presence of restrictions, such as toll stations, which will limit the actual speed.

NOTE: Electronic maps may provide additional information on local speed limits, trip duration, trip distance, and local elevation with respect to sea level.

| Parameter | Boundary condition |

| Ambient temperature (Tamb in degrees Celsius (°C)) | Moderate: 0 ≤Tamb < 30(1) |

| Extended (low): -7 ≤Tamb < 0(1) | |

| Extended (high): 30 <Tamb ≤35 | |

| Altitude (halt in meters above sea level) | Moderate: halt ≤700 |

| Extended: 700 <halt ≤1,300 | |

| Driving dynamics encompassing the effects of road grade, wind, driving dynamics (accelerations, decelerations), and auxiliary systems upon the energy consumption and pollutant emissions of the test vehicle | Road grade evaluated as cumulative positive elevation gain of a RDE trip (<1,200 m/100 km) |

| Overall excess or insufficiency of driving dynamics during the trip assessed by means of dynamic parameters like acceleration, v∙a+ or RPA | |

| Trip coverage and completeness checked by the MAW and the Power Binning methods | |

| Vehicle temperature condition(2) | No vehicle conditioning prescribed |

| Cold start period of up to 5 minutes excluded | |

| After-treatment condition(2) | Under certain conditions: the periodic regeneration of emissions control systems, e.g., Diesel Particulate Filters (DPF), may be excluded or the test may be repeated |

| Auxiliary systems | The air conditioning system or other auxiliary devices shall be operated as used by the consumer during real-world driving |

| Vehicle payload and test mass | Up to 90% of the allowed payload (including driver, a witness of the test, if applicable, the test equipment with the mounting and the power supply devices); artificial payload may be added |

| (1) By way of derogation, between the start of the application of binding not-to-exceed (NTE) emission limits as defined in section 2.1 of Annex IIIa to Regulation (EC) No 692/20088 and until five years after the dates given in paragraphs 4 and 5 of Article 10, of Regulation (EC) No 715/20072, the lower temperature for moderate conditions shall be greater or equal to 3 °C and the lower temperature for extended conditions shall be greater or equal to -2 °C. | |

| (2) Dedicated cold-start provisions will be implemented as part of the 3rd RDE regulatory package. Specific prescriptions regarding cold start duration and/or distance, control for status of periodically regenerating after-treatment systems, engine conditioning and vehicle soaking will be given as well. | |

Table 3: Boundary conditions of a valid RDE test12. The boundary conditions refer to the initial conditions that have to be respected before and during the test trip. For each condition, the limits and some comments are given.

| Parameter | Requirement |

| Distance-specific urban, rural and motorway shares (selected based on a street map)(1) | 34%, 33%, and 33% with a ±10% tolerance (urban shares must be major than 29%) |

| Definition of U/R/M driving based on instantaneous vehicle speed v(2) | Urban: vehicle speed v ≤60 km/hr |

| Rural: vehicle speed 60 <v ≤90 km/hr | |

| Motorway: vehicle speed v >90 km/hr | |

| Distance of urban, rural and motorway portions(2) | Minimum distance of 16 km |

| Speed of urban, rural and motorway portions(2) | Urban: average speed 15-40 km/hr; urban operation consisting of several stop periods of 10 sec or longer(3) |

| Stop periods(4): 6-30% of the time duration of urban operation | |

| Motorway: proper coverage of speeds between 90 and at least 110 km/hr | |

| v >100 km/hr for at least 5 min | |

| Maximum vehicle speed(2) | v ≤145 km/hr (may be exceeded by 15 km/hr for not more than 3% of the time duration of motorway portion) |

| Trip duration(2) | Between 90 and 120 min |

| Other requirements | The start and the end point shall not differ in their elevation above sea level by more than 100 m |

| RDE tests conducted on normal work days and hours(1) | |

| Maximum possible continuity for urban, rural and motorway portions(1,2) | |

| (1) to be verified when designing or executing the trip. | |

| (2) to be verified after the completion of the trip. | |

| (3) if a stop period lasts more the 180 sec, the emission events during the 180 sec following such excessively long stop period shall be excluded from the evaluation. | |

| (4) defined as vehicle speed of less than 1 km/hr. | |

Table 4: Operational requirements for a valid RDE test12. The operational requirements refer to the conditions that have to be respected during the test trip. For each condition, the limits and some comments are given.

4. Conduct the Trip

- Switch on the PEMS and let it stabilize for about 40 min, according to the specifications of the PEMS manufacturer.

- To avoid humidity condensation and to ensure appropriate penetration efficiencies of the various gases, ensure that the sampling line(s) have reached a minimum temperature of 60 °C, with or without cooler, for the measurement of gaseous pollutants. For particles, the minimum temperature is 100 °C.

- Confirm that the PEMS is free of warning signals and error indications. In case of warning messages, refer to the PEMS manual troubleshooting section.

- Choose the calibration gases to match the range of pollutant concentrations expected during the trip (i.e., the calibration range should cover at least 90% of the concentration values obtained from 99% of the measurements of the valid parts of the emissions test). For CO2, a range of 10-14% is recommended, while for NOx, around 1,500-2,000 ppm is recommended. The true concentration of a calibration gas has to be within ± 2% of the stated figure.

- Perform zero and span calibration adjustments of the analyzers using the calibration gases.

- Connect the zero gas (N2) or synthetic air or use the ambient air as zero gas.

- Prepare the software (e.g., Sensor's Tech). Select Test → Session Manager → Give a name → Open (a session) → Pre Test options: Zero.

- Disconnect the zero gas.

- Connect the span gas bottle to the PEMS at a pressure of 1 bar.

- Prepare the software. Select Test → Session Manager → Pre Test options: Span.

- Insert the concentrations of the gases in the bottle in the PEMS software (under the zero/span graphic user interfaces). The PEMS software automatically detects the analyzer response and compares it with the bottle value. The system automatically adjusts the response of the analyzer to the span value.

- Disconnect the span gas and connect the next one.

NOTE: The user has the option to use one span bottle with all relevant gases (at least CO2 and NOx) or separate gas bottles.

- When everything is ready, start the sampling measurement. Create a file name in the "Test name" tab.

- Before starting the engine, start recording the parameters by pressing "Start" in the Session Manager via the PEMS software already installed on the PC. To facilitate time alignment, start recording the parameters either in a single data recording device or with a synchronized time stamp.

NOTE: Commands to start and stop sampling and to start and stop recording are available in the PEMS software, which was previously installed on a PC and connected via an Ethernet cable to the PEMS main unit. Different software and graphic user interfaces are adopted by the PEMS manufacturers.

- Before starting the engine, start recording the parameters by pressing "Start" in the Session Manager via the PEMS software already installed on the PC. To facilitate time alignment, start recording the parameters either in a single data recording device or with a synchronized time stamp.

- Conduct the mapped trip by following the instructions of a navigation system. The trip should last 90-120 min. Drive normally, avoiding excessively timid or aggressive driving. Respect all local and national road safety rules. The air conditioning system or other auxiliary devices can be operated in a way that is compatible with their possible use by the consumer.

- Continue sampling, measuring, and recording the parameters throughout the on-road test. The engine may be stopped and started, but the emissions sampling and parameter recording must continue. Measurement and data recording may be interrupted for less than 1% of the total trip duration, but for no more than a consecutive period of 30 sec, solely in the case of unintended signal loss or for the purpose of PEMS system maintenance.

- Document any warning signals suggesting malfunction of the PEMS.

- At the end of the trip, switch off the combustion engine. Continue the data recording until the response time of the sampling systems has elapsed (approximately 20 sec). Press "Stop" in the Session Manager.

- At the end of the test and before the analyzers are turned off, check the drift of the analyzers, which measured the zero and the span, using the calibration gases that were used before the test, as follows. Follow the procedure in step 4.3, with the difference of selecting Zero and Span from the "Post Test" window.

- Measure the zero level of the analyzer(s). Check that the difference between the pre-test and post-test results complies with the requirements specified by Appendix 18. For example, for NOx, the permissible zero drift is 5 ppm.

- Measure the span level of the analyzer(s). It is permissible to zero the analyzer prior the span drift verification, if the zero drift was determined to be within the permissible range. Check that the difference between the pre-test and post-test results complies with the requirements specified by Appendix 18. For example, for NOx, the permissible zero drift is 5 ppm and the permissible span drift is 5 ppm, or 2% of the reading (whichever is larger).

- If the difference between the pre-test and post-test results for the zero and span drift is higher than permitted, void the test results and repeat the test.

5. Verify the Trip

- Export the recorded data to a spreadsheet file. In "Data Files," upload the file created before the tests. Then, in "Data Analysis," choose "Process the file."

NOTE: In the "Settings" tab, ensure that the settings are correct; if in doubt, use the default values from the manufacturer. In the "Output" tab, select the signals you want to export (typically all of them). - Check that (i) the parameter recordings reached the required data completeness of more than 99%, (ii) the calibrated range of the analyzers accounts for at least 90% of the concentration values obtained from 99% of the measurements of the valid parts of the emissions test, and (iii) less than 1% of the total number of measurements used for evaluation exceed the calibrated range of the analyzers by up to a factor of two. If these requirements are not met, the test must be voided.

- Based on the exported data, check the compliance with the boundary conditions (Table 3).

- Verify the conformity to the boundary conditions for ambient temperature and altitude, as specified in Table 3, by checking the instantaneous ambient humidity and temperature data, respectively.

- Check that the trip duration is between 90 and 120 min.

- Check the shares of urban, rural, and motorway driving; the maximum vehicle speed; the average speed; and idling shares of urban driving and confirm that they comply with Table 3.

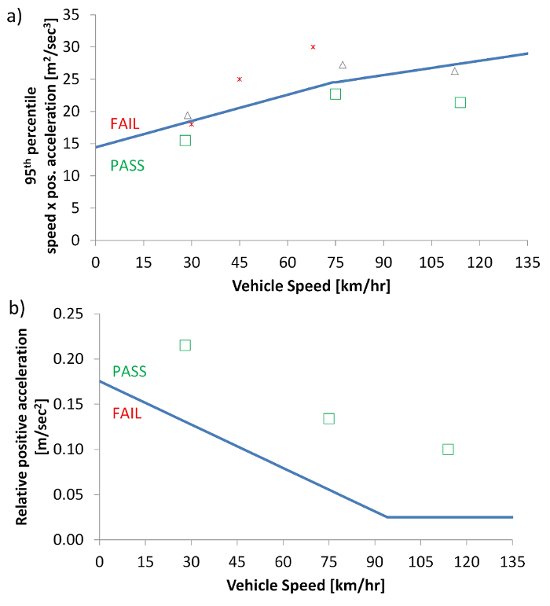

- Verify the excess or absence of driving dynamicity, as specified by the product of instantaneous vehicle speed and positive acceleration (v∙a+), and the Relative Positive Acceleration (RPA) (see Chapter 5 and Appendix 7a)13,14.

- Verify the realized altitude profiles (i.e., the trip cumulative positive elevation gain and the difference in elevation between the start and end points of a trip) (Chapter 6 and Appendix 7b)13,14.

- Based on the exported data, check the compliance with the operational requirements (Table 4). Verify that a sufficient coverage of normal dynamicity was achieved during the test (Table 4), applying the moving averaging windows (MAW) and/or the power binning methods on the basis of composite parameters, such as CO2, that encompass the effects of road grade, wind, driving dynamics, (e.g., accelerations, decelerations), and auxiliary systems upon vehicle energy consumption and emissions (see Appendices 5 and 613).

6. Calculate the Emissions

- Calculate the RDE emission result for all events within the boundary of normal driving dynamics using the MAW and/or the power binning methods. For Sensor's Tech PC software, this is done automatically if, in the "Settings" tab, the "Window" method was selected.

- Calculate the ratio of RDE emissions to the emission limit of the specific pollutant. A vehicle passes the test if the pollutant emissions remain below the applicable conformity factor (see Chapter 2)8 using at least one of the two methods (MAW or power binning). For NOx, this factor is 2.1 from 2017-2019 (new type approvals/new registrations) and will be lowered to 1.5 in 2020-2021.

NOTE: At the end of the trip, most calculations and emissions reports are done automatically, as most PEMS manufacturers offer suitable calculation software. Alternatively, the free software EMROAD (for MAW) or CLEAR (for power binning) can be used to execute step 5 (verify the trip).

Representative Results

An example of the function of the RDE requirements will be given.

Select and prepare the vehicle and design and conduct the trip: This was not a type approval test but an application of the RDE procedures. Thus, the selected vehicle, a Euro 5B light-duty turbocharged gasoline direct injection vehicle (1.2-L engine displacement), was already available in the JRC laboratory. An RDE-compliant trip was selected (Figure 3). After installation and preparation of the PEMS, the trip was conducted.

Figure 3: Trip design. A trip that includes urban (≤60 km/hr), rural, and motorway (>90 km/hr) parts in equal shares is shown. The design is based on the speed limits of the chosen roads. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Verify the trip: The trip was verified by checking (i) the boundary and operation conditions and (ii) the normality of driving. The boundary and operation conditions and the trip requirements were fulfilled (Table 5). The ambient temperature and the maximum altitude were both within the moderate limits of 0-30 °C and ≤700 m, respectively. The trip consisted of urban driving followed by rural and motorway driving. It lasted 96 min and covered a distance of at least 16 km for each of the U/R/M portions. The distance shares were within 29-44% for the urban part and 23-43% for the rural and motorway parts. The trip showed stop periods, defined as periods with a vehicle speed of less than 1 km/hr, in the prescribed range of 6-30% of the urban operation duration. As far as the vehicle speed profiles are concerned, the test showed a motorway operation that properly covered (i) the range between 90 and 110 km/hr and (ii) speeds above 100 km/hr for at least 5 min. The maximum vehicle speed was well below the threshold of 145 km/hr, while the average speed of the urban driving part of the trip, including stops, was within the permissible range of 15-40 km/hr. The cumulative positive elevation gain over the entire trip was below the limit of 1,200 m per 100 km. The altitude difference between the start and end points was <100 m. The relative positive acceleration and the 95th percentiles of the speed multiplied by the positive acceleration were within the limits (see Figure 4). Experimental data with more aggressive driving using the same car, as well as other tests reported in the literature, are shown for comparison17,18.

Figure 4: Indices to check the excess or absence of driving dynamics. (a) 95th percentile of the product of instantaneous speed and positive acceleration during urban, rural, and motorway driving. (b) Relative positive acceleration during urban, rural, and motorway driving. The open squares are the experimental results. The open triangles are results with aggressive driving in the same car. The asterisks are aggressive trips in German cities. The continuous line shows the permitted limits. The pass or fail areas are also shown. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| Conditions | Units | Limits | Trip | Urban | Rural | Motorway | Comments |

| Speed | [km/hr] | ≤60 | 60<v ≤90 | v>90 | |||

| Payload | [%] | 90 | 75 | ok | |||

| Ambient temperature | [°C] | -7…+35 | 19 | ok (moderate) | |||

| Max. altitude | [m] | ≤1,300 | 302 | ok (moderate) | |||

| Start/End altitude difference | [m] | <100 | 40 | ok | |||

| Cumulative positive elevation gain | [m/100 km] | <1,200 | 636 | ok | |||

| Relative Positive Acceleration | [m/sec2] | Figure 4 | 0.215 | 0.134 | 0.100 | ok | |

| speed x positive acceleration | [m2/sec3] | Figure 4 | 15.5 | 22.7 | 21.4 | ok | |

| Trip duration | [sec] | 90-120 | 96 | ok | |||

| Distance covered | [km] | >16 | 29 | 27 | 23 | ok | |

| Share | [%] | 23(29)-43 | 36.7 | 34.2 | 29.1 | ok | |

| Stop time (of Urban duration) | [%] | 6-30 | 28.8 | ok | |||

| v>100 km/hr | [min] | ≥5 | 9.7 | ok | |||

| v>145 km/hr (of Motorway time) | [%] | <3 | 0 | ok | |||

| Average speed (Urban part) | [km/hr] | 15-40 | 28 | 75 | 114 | ok |

Table 5: Summary of trip evaluation. The boundary conditions; the test requirements; and the results obtained before and/or during the trip for the urban, rural, and motorway portions, respectively, are listed.

The normality of driving was conducted with the MAW evaluation method, excluding cold start and idling and weighing the NOx emissions with CO2 emission deviations greater than 25% of the type approval cycle according to the MAW method (see Appendix 5)8. The free EMROAD software was used.

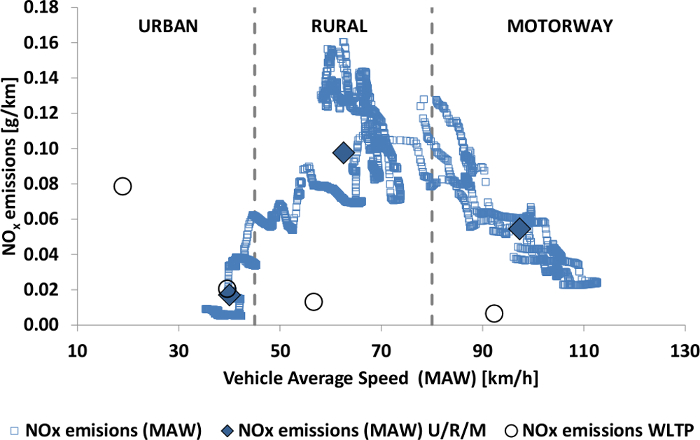

Calculate the RDE emissions: The analysis of the results was also conducted with the EMROAD software. The results can be seen in Figure 5. The urban NOx emissions were at the same level as or lower than the respective WLTC phases emissions (0.02 g/km). The rural and motorway emissions were >0.05 g/km higher than the respective WLTC phases. On average, the on-road emissions were 0.056 g/km, which is lower than the NTE limit (for this case, 0.06 mg/km x 2.1 conformity factor). Thus, this specific vehicle would pass the RDE test (even though the RDE procedure is not applicable to Euro 5 vehicles). More examples can be found elsewhere17-18.

Figure 5: MAW NOx emissions of the road trip as a function of the MAW speed. The blue squares show the average NOx emissions of each moving averaging window as a function of the respective window-average vehicle speed. Solid diamonds depict the mean on-road NOx emissions of all windows representing urban, rural, and motorway driving. White circles depict the laboratory NOx emissions over the four phases of the WLTP. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

In this paper, the RDE procedure was described. Several points deserve special attention and will be discussed in more detail here.

For type approval purposes, it is obligatory to determine the exhaust gas flow using equipment such as an EFM functioning without any connection to the ECU of the vehicle. Regarding vehicle preparation, the connection between the EFM and the tailpipe is important. The materials should be temperature- and exhaust gas composition-resistant. Although this is not so critical for NOx, it will be significant for particle number sampling, where desorption of deposited material can lead to artificially high emissions. In addition, points that can accumulate condensates should be avoided. The condensates formed during accelerations can enter into the measurement systems and damage or block them. The sampling points of the analyzers are connected downstream of the EFM in order to ensure that the whole flow passes through the EFM. In case this is not possible and they are connected upstream of the EFM, a correction for the extracted flow has to be made. The analyzers should be connected downstream of the EFM, without any modifications to the length of the sampling lines. If this is not possible, the residence time in the extra tubing has to be taken into account in the software in order to ensure correct emission calculations. The analyzers can be installed inside or outside of the vehicle, as long as safety requirements are met. Moreover, the calibration of the analyzers requires attention. It has to be done within the expected range of emissions of the vehicle. Otherwise, the requirement of 90% coverage of 99% of the measurements of the valid parts of the emissions test might not be fulfilled.

The trip verification and the calculation of the emissions are typically conducted by the PEMS software. For normal driving, all conditions can be easily met17. For example, based on our measurements, a normally driven trip is well within the dynamic boundary limits (Figure 4). However, aggressive driving can be within the pass zone, especially during the urban or motorway portions. On the other hand, data in Dutch cities show that normal driving can also exceed these limits18. In the future, experience over time, tests conducted closer to the boundary conditions, and evaluation methods that show differences of >50% will assess the applicability of the procedure11,19.

A source of uncertainty originates from the determination of road loads for the measurement of CO2 emissions with the WLTC; these measurements are used to evaluate the normality of driving conditions with the RDE data evaluation. Ideally, the chosen road loads resemble those of the unloaded vehicle tested with the PEMS on the road. The flexibilities granted in by the WLTP (e.g., to determine the road load based on conservative generic parameters or the vehicle with the highest test mass within a family) may cause substantial deviations in the CO2 emissions determined by the WLTC and measured later on the road. In consequence, the methods may yield a biased evaluation of the actual driving severity. The WLTP provisions for setting the road load may potentially need to be specified for RDE purposes.

It should be noted that, in comparison to the European heavy-duty in service conformity regulation, there are some differences (e.g., drift correction is allowed, OBD connection is necessary in order to calculate emissions in g/kWhr) due to the different type approval procedure for the heavy-duty vehicles (engines)6. The differences are out of the scope of this paper. With the US in-use-compliance regulation, there are more differences in the evaluation method.

Worldwide, RDE marks the first regulatory on-road test for light-duty vehicles. The RDE provisions defined in Regulation 2016/427 mark the first relevant instance for the type approval of light-duty vehicles in Europe, where RDE complements the standard vehicle testing under controlled conditions in the laboratory. The RDE test procedure allows for testing, and thus controlling, vehicle pollutant emissions under a wide range of operating conditions and in a more robust and comprehensive manner than the currently-applied laboratory testing with a predefined driving cycle.

Nevertheless, RDE is also subject to limitations. First, modal emission measurements on the road over long time periods entails the risk of analyzer drift (e.g., due to variability in ambient temperature). On-road emission measurements are thus subject to larger uncertainty margins (estimated at a maximum of 20-30% at the applicable emissions limit for NOx)21 than emission measurements in the laboratory, even if PEMS analyzers fulfill similar requirements regarding accuracy and precision as laboratory analyzers. Second, the handling of PEMS equipment requires training; conducting emission tests on the road is not yet plug-and-play, and it requires an expert. As on-road testing with PEMS is still rather novel, training that allows auto makers and technical services to acquire and share best practices is needed. The present article is an attempt to disseminate knowledge on the handling of PEMS and the testing of vehicle emissions on the road. Larger-scale experience with the RDE provisions, as can be obtained by inter-laboratory exercises or through benchmarking against existing international legislation, is still missing. As RDE constitutes the first on-road test procedure for light-duty vehicles worldwide, the European Commission foresees an annual review of conformity factors and a more comprehensive review of the entire RDE procedure in the midterm.

There are two major areas for future application. First, RDE may be adopted by other countries. China, India, Japan, and South Korea are interested in adopting RDE, or elements thereof, for regulatory purposes. As such, the procedure described here may become the blueprint for regulatory on-road emissions testing of light-duty vehicles around the world. Second, RDE presents a good practice guide for any independent emission test performed by research institutions and technical services. The provisions help ensure accurate and robust on-road emission measurements.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Sensors Inc. for providing a PEMS for conducting an inter-laboratory exercise.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| PEMS analyzer | Sensors Inc. | SEMTECH ECOSTAR | |

| PEMS analyzer | AVL | MOVE | Figure 2 |

| PEMS analyzer | Horiba | OBS | Figure 2 |

| PEMS analyzer | MAHA | PEMS-GAS | Figure 2 |

| Exhaust Flow meter | Sensors Inc. | SEMTECH EFM-HS | EFM-HS specifications of Table 4 |

| GPS | Garmin | Drive 50 | |

| Weather station | Waisala | AWS310 | |

| Zero gas | Air Liquide | AL089 | Alphagaz 1 (N2) |

| Span gas | Air Liquide | SM190022710IT | 1800 ppm NO in N2 |

| Span gas | Air Liquide | SM190022710IT | 13% CO2 in N2 |

| Batteries | Discover | EV12A-A | |

| Mention of trade names or commercial products does not constitute endorsement or recommendation by the authors or the European Commission | |||

References

- . . Regulation No 83 on uniform provisions concerning the approval of vehicles with regard to the emission of pollutants according to engine fuel requirements, Addendum 82: Regulation No 83, Revision 4. , (2012).

- . Regulation No. 715/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 June 2007on type-approval of motor vehicles with respect to emissions from light passenger and commercial vehicles (Euro 5 and Euro 6) and on access to vehicle repair and maintenance information, European Commission (EC). Official J. European Union. L 171, 1-16 (2007).

- Tietge, U., et al. . From laboratory to road: a 2015 update of official and "real-world" fuel consumption and CO2 values for passenger cars in Europe. ICCT white paper. , (2015).

- Weiss, M., et al. On-road emissions of light-duty vehicles in Europe. Environ. Sci. Technol. 45, 8575-8581 (2011).

- . Determination of PEMS measurement allowances for gaseous emissions regulated under the heavy-duty diesel engine in-use testing program. Revised Final report Available from: https://www.regulations.gov/document?D=EPA-HQ-OAR-2004-0072-0085 (2008)

- Vlachos, T., et al. In-use emissions testing with Portable Emissions Measurement Systems (PEMS) in the current and future European vehicle emissions legislation: Overview, underlying principles and expected benefits. SAE Int. J. Commer. Veh. 7 (1), 199-215 (2014).

- Vlachos, T., et al. Evaluating vehicles real-driving emissions performance: a challenge for the emissions control legislation. VDI Research Reports. , (2015).

- Hausberger, S., et al. Experiences with current RDE legislation. , (2015).

- Demuynck, J., et al. Euro 6 Vehicles' RDE-PEMS Data Analysis with EMROAD and CLEAR. , (2016).

- . Commission Regulation 2016/427. Amending Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 as regards emissions from light passenger and commercial vehicles (Euro 6)). Annex IIIA of the Commission Regulation (EC) No. 692/2008 (2016). Verifying Real Driving Emissions. Official J. European Union. L 82, 1-97 (2016).

- . Commission Regulation 2016/646. Amending Regulation (EC) No 692/2008 as regards emissions from light passenger and commercial vehicles (Euro 6). Annex IIIA of the Commission Regulation (EC) No. 692/2008 (2016). Verifying Real Driving Emissions. Official J. European Union. L 109, 1-22 (2016).

- . Commission Regulation (EC) No. 692/2008 of 18 July 2008 implementing and amending Regulation (EC) No 715/2007 of the European Parliament and of the Council on type-approval of motor vehicles with respect to emissions from light passenger and commercial vehicles (Euro 5 and Euro 6) and on access to vehicle repair and maintenance information, European Commission (EC). Official J. European Union. L 199, 1-135 (2008).

- . On-road determination of average Dutch driving behaviour for vehicle emissions. TNO Report 2016 R 10188 Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303809697_On-road_determination_of_average_Dutch_driving_behaviour_for_vehicle_emissions (2016)

- Bosteels, D. Real Driving Emissions and Test Cycle Data from 4 Modern European Vehicles. , (2014).

- Vlachos, T., et al. The Euro 6 Real-Driving Emissions (RDE) procedure for light-duty vehicles: Effectiveness and practical aspects. , (2016).

- Giechaskiel, B., et al. Vehicle emission factors of solid nanoparticles in the laboratory and on the road using Portable Emission Measurement Systems (PEMS). Front. Environ. Sci. 3 (82), (2015).

- . Preliminary uncertainty assessment. Presentation given to the European Commission, RDE Task Force on Uncertainty Evaluation Available from: https://circabc.europa.eu/sd/a/a4c8455f-de18-4f3a-9571-9410827c4f87/2015_10_01_Error_analysis_JRC.pdf (2015)

Explore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

ABOUT JoVE

Copyright © 2024 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved