CRISPR-mediated Genome Editing of the Human Fungal Pathogen Candida albicans

In This Article

Summary

Efficient genome engineering of Candida albicans is critical to understanding the pathogenesis and development of therapeutics. Here, we described a protocol to quickly and accurately edit the C. albicans genome using CRISPR. The protocol allows investigators to introduce a wide variety of genetic modifications including point mutations, insertions, and deletions.

Abstract

This method describes the efficient CRISPR mediated genome editing of the diploid human fungal pathogen Candida albicans. CRISPR-mediated genome editing in C. albicans requires Cas9, guide RNA, and repair template. A plasmid expressing a yeast codon optimized Cas9 (CaCas9) has been generated. Guide sequences directly upstream from a PAM site (NGG) are cloned into the Cas9 expression vector. A repair template is then made by primer extension in vitro. Cotransformation of the repair template and vector into C. albicans leads to genome editing. Depending on the repair template used, the investigator can introduce nucleotide changes, insertions, or deletions. As C. albicans is a diploid, mutations are made in both alleles of a gene, provided that the A and B alleles do not harbor SNPs that interfere with guide targeting or repair template incorporation. Multimember gene families can be edited in parallel if suitable conserved sequences exist in all family members. The C. albicans CRISPR system described is flanked by FRT sites and encodes flippase. Upon induction of flippase, the antibiotic marker (CaCas9) and guide RNA are removed from the genome. This allows the investigator to perform subsequent edits to the genome. C. albicans CRISPR is a powerful fungal genetic engineering tool, and minor alterations to the described protocols permit the modification of other fungal species including C. glabrata, N. castellii, and S. cerevisiae.

Introduction

Candida albicans is the most prevalent human fungal pathogen1,2,3. Understanding differences between C. albicans and mammalian molecular biology is critical to development of the next generation of antifungal therapeutics. This requires investigators to be able to quickly and accurately genetically manipulate C. albicans.

Genetic manipulation of C. albicans has historically been challenging. C. albicans does not maintain plasmids, thus all constructs must be incorporated into the genome. Furthermore, C. albicans is diploid; therefore, when knocking out a gene or introducing a mutation, it is important to ensure that both copies have been changed4. In addition, some C. albicans loci are heterozygous, further complicating genetic interrogation5. To genetically manipulate C. albicans, it is typical to perform multiple rounds of homologous recombination6. However, the diploid nature of the genome and laborious construct development have made this a potentially tedious process, especially if multiple changes are required. These limitations and the medical importance of C. albicans demand the development of new technologies that enable investigators to more easily manipulate the C. albicans genome.

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR)-mediated genome editing is a powerful tool that allows researchers to change the sequence of a genome. CRISPR requires three components: 1) the Cas9 nuclease that cleaves the target DNA, 2) a 20 base guide RNA that targets Cas9 to the sequence of interest, and 3) repair template DNA that repairs the cleavage site and incorporates the intended change7,8. Once the guide brings Cas9 to the target genome sequence, Cas9 requires a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequence (NGG) directly upstream of the guide sequence to cleave the DNA9. The requirement for both the 20 base guide and PAM sequences provides a high degree of targeting specificity and limits off-target cleavage.

CRISPR systems have been designed to edit the genomes of a diverse set of organisms and tackle a wide variety of problems10. Described here is a flexible, efficient CRISPR protocol for editing a C. albicans gene of interest. The experiment introduces a stop codon to a gene, causing translation termination. Other edits can be made depending on the repair template that is introduced. A fragment marked with nourseothricin (Natr) containing yeast codon-optimized Cas9 (CaCas9) and a guide RNA is incorporated into the C. albicans genome at a neutral site. Cotransformation with the repair template encoding the desired mutation leads to repair of the cleavage by homologous recombination and efficient genome editing. Described below is the editing of TPK2, but all C. albicans open reading frames can be targeted multiple times by CRISPR. The CRISPR system is flanked by FRT sites and can be removed from the C. albicans genome by induction of flippase encoded on the CaCas9 expression plasmid. The C. albicans CRISPR system enables investigators to accurately and quickly edit the C. albicans genome11,12.

Protocol

1. Identification and Cloning of Guide RNA Sequence

- Identification of guide RNA sequence

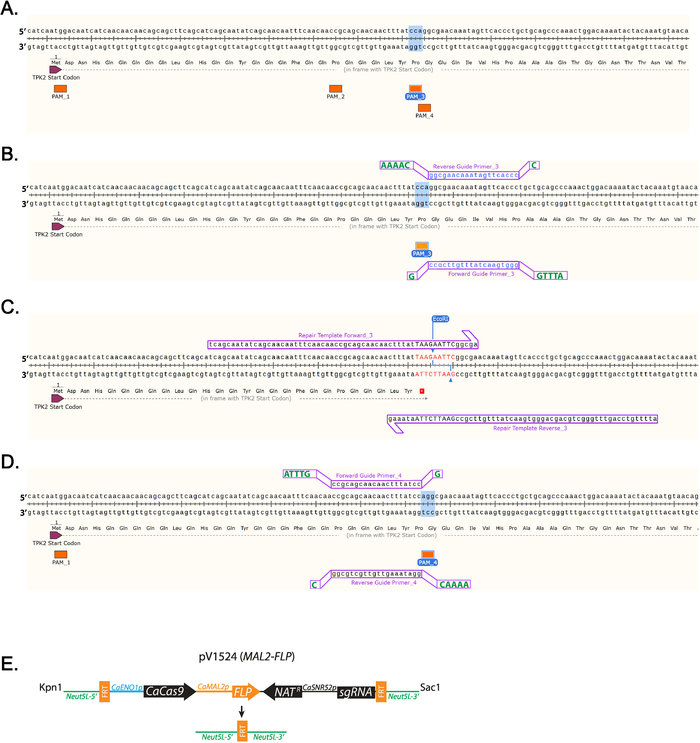

- Identify a 5’-NGG-3’ PAM sequence close to where the stop codon will be inserted. (Figure 1A) Labeled are all PAM sequences found in the first 100 base pairs of TPK2 (Figure 1A).

NOTE: Guide sequences targeting each C. albicans open reading frame can be found at http://osf.io/ARDTX 11,12. - Identify the Forward Guide Primer_3 sequence, which will be the 20 bases directly upstream of a NGG PAM site and will not contain more than 5 Ts in a row. Left-click on the base directly upstream of the NGG and drag the cursor 20 bases, then left-click on the primer tab to add the primer.

- Identify the Reverse Guide Primer_3 sequence, which will be the complement to the Forward Guide sequence.

NOTE: Shown are guides that use PAM_3 (Figure 1B). - Right-click the primer and select “copy primer data”. Paste the sequences into a text editing program.

- Identify a 5’-NGG-3’ PAM sequence close to where the stop codon will be inserted. (Figure 1A) Labeled are all PAM sequences found in the first 100 base pairs of TPK2 (Figure 1A).

- Add overhang sequences to Forward and Reverse Guide oligos to facilitate cloning (Table 1, Figure 1B).

- Add the nucleotide sequence ATTTG to the 5’ end of the Forward Guide Primer_3 before purchasing.

- Add G to the 3’ end of the Forward Guide Primer_3 before purchasing.

- Add the nucleotide sequence AAAAC to the 5’ end of the Reverse Guide Primer_3 before purchasing.

- Add C to the 3’ end of the Reverse Guide Primer_3 before purchasing.

- Digest CaCas9 expression vector pV1524 with BsmBI.

NOTE: pV1524 contains an ampicillin (Ampr) and nourseothricin (Natr) markers. Cas9 has been codon-optimized for C. albicans.- Digest the plasmid by adding: 2 μg of pv1524, 5 μL of 10x Buffer, 1 μL of BsmBI, and H2O to 50 μL in a 1.5 mL tube. Incubate at 55 °C for 20 min. (Alternatively, digest pv1524 for 15 min with Esp3I, an isoschizomer of BsmBI, at 37 °C.)

- Cool to room temperature (RT) and spin for 30 s at 2,348 x g to bring condensation to the bottom of the tube. Proceed to step 1.4 or store the digested plasmid at -20 °C.

- Phosphatase-treat the digested backbone.

- Add 1 μL of calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) to the digestion mixture and incubate at 37 °C for 1 h.

- Purify the digested plasmid using a commercially available polymerase chain reaction (PCR) purification kit (instructions provided with kit) and elute it in 30 μL of elution buffer (EB).

- Phosphorylate and anneal Forward Guide Primer_3 and Reverse Guide Primer_3.

- Add 0.5 μL of 100 μM Forward Guide Primer_3, 0.5 μL of 100 μM Reverse Guide Primer_3, 5 μL of 10x T4 ligase buffer, 1 μL of T4 polynucleotide kinase, and 43 μL of H2O to a PCR tube.

- Add 5 μL of 10x T4 ligase buffer, 1 μL of T4 polynucleotide kinase, and 44 μL of molecular biology-grade H2O in a second PCR tube.

NOTE: This will serve as the negative control. - Incubate the reaction mixtures in a thermocycler at 37 °C for 30 min, then at 95 °C for 5 min.

- Cool the mixture at the slowest ramp rate to 16 °C to anneal the ,oligos. Then place the annealed oligo mixture at 4 °C.

- Ligate the annealed oligos into digested pv1524 from step 1.4.3.

- Add the following to a PCR tube: 1 μL of 10x T4 ligase buffer, 0.5 μL of T4 DNA ligase, 0.5 μL of annealed oligo mix, digested CIP-treated purified plasmid (20–40 ng), and H2O to a 10 μL total volume.

- Add the following to a PCR tube: 1 μL of 10x T4 ligase buffer, 0.5 μL of T4 DNA ligase, digested CIP-treated purified vector (20–40 ng), 1 μL of negative control mixture, and H2O up to a 10 μL total volume.

- Incubate both tubes in a thermocycler at 16 °C for 30 min, then at 65 °C for 10 min, then cool to 25 °C.

- Transform 5 μL of the ligation mixtures into chemically competent Escherichia coli DH5α using a standard heat shock transformation protocol. Select on LB Amp/Nat media (200 μg/mL Amp, 50 μg/mL Nat).

NOTE: Failure to select pV1524 and its derivatives on double selection media will result in loss of Nat/CaCas9/guide module by FLP/FRT excision in bacteria. - Purify plasmids from four transformants by miniprep, and sequence the insertion sequence with sequencing primer (Table 1).

Note: Most of the time, sequencing 4 transformants is sufficient to identify at least 1 correct clone. - Save plasmids that have the guide RNA sequence cloned a single time into the BsmBI cut site at -20 °C.

2. Designing and Generation of Repair Template

- Insert a stop codon by left-clicking in the gene sequence and adding nucleotides that encode a stop codon and restriction digestion site (Figure 1C, Table 1).

NOTE: The insertion will disrupt the PAM sequence.

NOTE: A restriction digestion site will be included in the repair template sequence to facilitate efficient screening of clones (Figure 1C). - Left-click 10 bases downstream of where the mutation will be made and drag the cursor 60 bases upstream. Left-click on the primer tab to add the primer. This will add Repair Template Forward_3. Left-click 10 bases upstream of where the mutation will be made and drag the cursor 60 bases downstream. Left-click on the primer tab to add the primer. This will add Repair Template Reverse 3. (Figure 1C)

- Perform primer extension to generate the repair template.

- Add 1.2 μL of 100 μm repair template forward primer, 1.2 μL of 100 μm repair template reverse primer, 6 μL of deoxynucleotide triphosphates (dNTPs) (total concentration 40 mM), 6 μL of buffer, 0.6 μL of Taq polymerase (3 units), and 45 μL of H2O to each of the 4 PCR tubes.

- Perform primer extension by running between 20 and 30 rounds of PCR. Example extension conditions: 2 min at 95 °C, (30 s at 95 °C, 1 min at 50 °C, 1 min at 68 °C) x 34, 10 min at 68 °C.

- Combine contents of all 4 PCR tubes in a 1.5 mL tube and use a PCR purification kit to purify products in 50 μL of H2O.

- Quantitate the primer extension products to ensure sufficient DNA by determining the absorbance at 260 nm.

NOTE: Typical final concentration of the primer extension product is ~200–300 ng/µL.

3. Transformation of C. albicans with Repair Template and Plasmid

- Make TE/lithium acetate.

- Mix 10 mM Tris-Cl, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM lithium acetate, and H2O (all stock solution pH 7.5) to achieve 50 mL total volume.

- Make PLATE

- Mix 40% PEG 3350, 100 mM lithium acetate, 10 mM Tris-Cl, 1 mM EDTA, and H2O (all stock solution pH 7.5) to achieve 50 mL total volume.

- Digest correctly-cloned plasmids from step 1.9.

- Add 10 μg of plasmid, 4 µL of 10x buffer, 0.4 µL of 10 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), 0.5 µL of KpnI, 0.5 µL of SacI, and H20 to 40 µL total volume in a 1.5 mL tube. Incubate at 37 °C overnight (Figure 1D).

- Grow an overnight culture of C. albicans SC5314, wild-type prototroph, at 25 °C in yeast peptone dextrose supplemented with 0.27 mM Uridine (YPD + Uri), ideally to OD600 less than 6.

- Pellet 5 OD600 units of cells per transformation by spinning for 5 min at 2,348 x g and suspend the 5 OD600 of pelleted cells in 100 µL TE/lithium acetate.

- Add the following to a 1.5 mL tube in the order listed: 1) 100 µL of cells from step 3.4.1, 2) 40 µL of boiled and quick-cooled salmon sperm DNA (10 mg/mL), 3) 10 µg of plasmid digestion from step 3.3.1, 4) 6 µg of purified repair template, and 5) 1 mL of PLATE.

- Add the following to a 1.5 mL tube in the order listed: 1) 100 µL of cells, 2) 40 µL of boiled and quick-cooled salmon sperm DNA (10 mg/mL), 3) H2O volume equal to that of transforming DNA in step 3.5, and 4) 1 mL of PLATE.

Note: This will serve as a negative control. - Mix the transformations gently by pipetting and let incubate at 25 °C overnight.

- Heat shock the cells by placing them in a 44 °C water bath for 25 min.

- Spin for 5 min at 2,348 x g in a benchtop centrifuge and remove the PLATE mixture supernatant. Wash once by adding 1 mL of YPD + Uri and centrifuge again for 5 min at 2,348 x g.

- Suspend the cells in 0.1 mL of YPD + Uri and incubate on a roller drum or shaker at 25 °C overnight.

- Plate on YPD + Uri with 200 μg/mL nourseothricin. Colonies will appear in 2–5 days.

4. Streaks for Single Colonies

- Divide a 100 mm x 15 mm Petri dish into quarters, and label each quadrant.

- Touch one of the colonies from the transformation plate with a sterile toothpick or applicator and streak across the longest side of the quadrant.

- Streak for single colonies using an aseptic technique and allow the colonies to grow at 30 °C for 2 days.

5. Colony PCR

- Design the forward check primer (FCP) ~200 base pairs upstream of the restriction site that was introduced and the reverse check primer (RCP) ~300 base pairs downstream.

- Add 0.3 μL of FCP, 0.3 μL of RCP, 0.3 μL of thermostable polymerase (ExTaq 1.5 units), 3 μL of dNTPs (total concentration 40 mM), 3 μL of ExTaq Buffer, and 23 μL of H2O to a 1.5 mL tube.

NOTE: Addition of 0.5 μL/reaction dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) can improve PCR efficiency. - Add 0.25 μL of a single yeast colony from step 4.1.2 to the mixture from step 5.1.1, using a P10 pipette tip and taking care not to disturb the agar.

- Amplify DNA by PCR and run 5 μL of the PCR on a gel to ensure amplification is successful, taking care not to disturb the cell pellet at the bottom of the tube.

- Add 0.3 μL of FCP, 0.3 μL of RCP, 0.3 μL of thermostable polymerase (ExTaq 1.5 units), 3 μL of dNTPs (total concentration 40 mM), 3 μL of ExTaq Buffer, and 23 μL of H2O to a 1.5 mL tube.

6. Restriction Digestion of Colony PCR

- Add 10 μL of PCR product (taking care not to not disturb the cell pellet at the bottom of the tube), 3 μL of buffer, 1 μL of restriction enzyme, and 16 μL of H2O, then incubate according to manufacturer’s instructions and resolve on an agarose gel to identify correct genome edits.

NOTE: The restriction enzyme used here is the site encoded in the TPK2 specific repair template.

7. Saving Strains

- Grow an overnight culture from colonies that have been confirmed by restriction digestion in YPD + Uri at 30 °C.

- Add 1 mL of culture and 1 mL of 50% glycerol (bringing the final concentration of glycerol to 25%) to a tube suitable for storage at -80 °C.

- Store the correct clones at -80 °C.

NOTE: Correct strains can be stored at -80 °C for many years.

8. Removal of Natr Marker

- Streak correct transformant onto yeast peptone maltose (YPMaltose) (2% maltose).

- Pick a colony from the streaked plate and culture the yeast for 48 h at 30 °C in liquid YPMaltose 20 g/L maltose.

- Plate 200–400 cells on YPMaltose 20 g/L maltose and incubate at 30 °C for 24 h.

- Replicate the plate onto YPMaltose and YPMaltose 200 μg/mL Nat.

- Incubate at 30 °C for 24 h.

NOTE: Colonies that no longer grow on YPMaltose 200 μg/mL nourseothricin but grow on YPMaltose have lost the Natr marker (CaCAS9) and guide RNA. - Save the strains that have lost the Natr marker (CaCAS9) and guide RNA as done in steps 7.1–7.3.

NOTE: A similar plasmid, pV1393, uses the SAP2 as opposed to a MAL2 promotor. Growth on YCB–BSA will induce flippase and removal of Natr if pV1393 is used for gene editing.

Representative Results

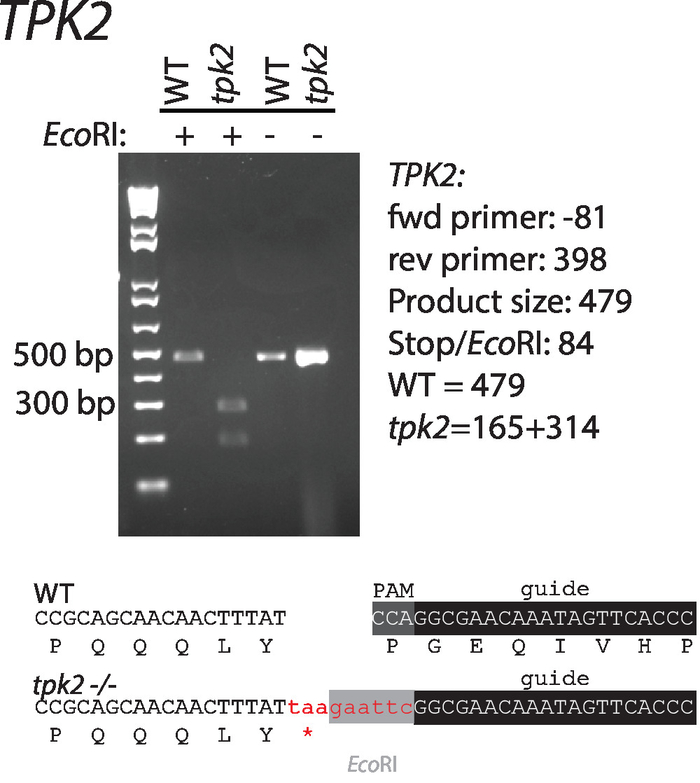

Sequences of guide RNAs and repair templates that target C. albicans TPK2, a c-AMP kinase catalytic subunit, were designed according to the guidelines suggested above. Sequences are shown in (Table 1, Figure 1). Guide RNAs were cloned into CaCas9 expression vectors and cotransformed with repair template in wild-type C. albicans. An EcoRI restriction digestion site and stop codons in the repair template disrupt the PAM site and facilitate screening for correct mutants (Figure 1). Transformants were streaked for single colonies and screened by colony PCR and restriction digestion for incorporation of the repair template (Figure 2). Restriction digestion quickly distinguishes wild-type from mutant sequences.

| Oligonucleotide Name | Oligonucleotide Sequence |

| Forward Guide Primer_3 | ATTTGgggtgaactatttgttcgccG |

| Reverse Guide Primer_3 | AAAACggcgaacaaatagttcacccC |

| Repair Template Forward_3 | tcagcaatatcagcaacaatttcaacaaccgcagcaacaactttatTAAGAATTCggcga |

| Repair Template Reverse_3 | attttgtccagtttgggctgcagcagggtgaactatttgttcgccGAATTCTTAataaag |

| Forward Check Primer | ttaaagaaacttcacatcaccaag |

| Reverse Check Primer | actttgatagcataatatctaccat |

| Sequencing Primer | ggcatagctgaaacttcggccc |

Table 1: List of oligo nucleotides used for this study. Sites added for cloning purposes are capitalized and bolded in the guide primer sequences. Sequences in the repair template that mutate the genomic DNA are capitalized and bolded.

Figure 1: Diagram of guide RNA and repair template design. (A) Labeling of all the PAM sequences in the first 100 nucleotides of TPK2. PAM sequence 3 (PAM_3) is highlighted, as that is the sequence used in this study. (B) Guide RNA design using PAM_3. 20 base primers designed using SnapGene are lowercase and blue. Additional bases required for cloning are uppercase and green shown offset. (C) Repair template primers that insert a TAA stop codon and EcoRI site are inserted into the TPK2 reading frame. DNA that differs from the wild-type sequence is red and uppercase. (D) Example of how a guide is designed on the positive strand of DNA using PAM_4. (E) Schematic diagram of pV1524 after cloning of the guide RNA and digestion with KpnI and SacI. Neut5L-5' and Neut5L-3' target the vector to the Neut5L site in the C. albicans genome. CaENO1p is the promotor that drives expression of the yeast-optimized CaCas9. Natr is the nourseothricin resistance cassette. CaSNR52p is the promotor driving guide RNA expression (sgRNA). FRT sites are cleaved and recombined by flippase (FLP) removing the CRISPR cassette upon flippase expression. A schematic similar to (E) was published by Vyas et al.11. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Introduction and confirmation of a stop codon and EcoRI restriction site to TPK2. Primers used for amplification are listed in Table 1. Wild-type and mutant sequences are shown below the gel. This figure has been modified from Vyas et al.11. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

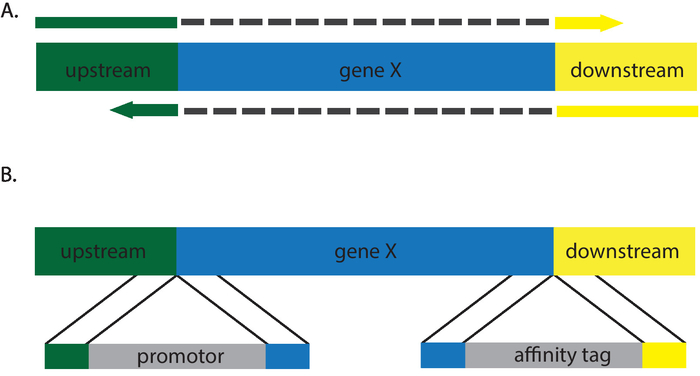

Figure 3: Cartoon description of repair templates that will generate (A) deletions and (B) insertions. Grey dashes in (A) depict intervening sequences not present in the repair template primers. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

C. albicans CRISPR efficiently edits the C. albicans genome. pV1524 encodes a yeast codon-optimized Cas9 and is designed such that investigators can easily clone guide RNA sequences downstream of the CaSNR52 promoter (Figure 1)11. It must be ensured that only a single copy of the guide sequence has been cloned into CaCas9 expression vectors by sequencing, as extra copies will impede genome editing. If multiple copies of the guide are introduced consistently, one should lower the concentration of the annealed guide used in ligation. The vector and protocol described allow targeting of any C. albicans gene. Although C. albicans is diploid, only a single transformation is required to target both alleles of a gene. Furthermore, the processive nature of CRISPR-CaCas9 genome editing enables researchers to target multiple members of gene families. Many gene families such as the secreted aspartyl proteases (SAPS) and agglutinin-like sequence proteins (ALS) are important for C. albicans virulence. CRISPR genome editing will facilitate investigation of these gene families.

The protocols described above introduce a stop codon to an open reading frame, resulting in the phenotypic equivalent of a null (Figure 2). A wide variety of genetic alternations can be made by varying the repair template. Nonsense, missense, and silent mutations can be inserted via recombination with an appropriate repair template. Incorporation of a restriction site streamlines transformant screening, as those without must be screened by sequencing12,13. In addition, C. albicans CRISPR enables researchers to generate insertions and deletions, making it an ideal system to insert affinity tags, perform promotor swaps, and generate knockouts (Figure 3). Screening for correct transformants for these mutations is more laborious, as it is necessary to sequence the edits to confirm correct incorporation of the repair templates. Furthermore, Southern blot may be necessary to ensure additional copies of a gene have not been inserted at additional locations in the genome. The requirement of the NGG PAM site places slight limitations on the regions of the genome that can be targeted. The development of alternative CRISPR systems that use alternative nucleases such as Cpf1 or variations on the Cas9 system have/will alleviate many of these limitations14. To the investigators' knowledge at this time, these systems have not yet been applied to C. albicans.

The CRISPR system described in the above protocol has been developed such that it can be applied in a wide variety of species including Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Naumouozyma castellii, and the human pathogen Candida glabrata11. Transformation and efficient editing of these yeast requires slight changes to the described protocol, but the framework for editing these alternate genomes is remarkably similar to that described for C. albicans12. Furthermore, yeast provide an excellent mechanism to develop genome editing procedures. In yeast, when ADE2 is mutated, a precursor to the adenine biosynthesis pathway accumulates, turning the cells red. This easily observable phenotype allows investigators to identify edited cells and quickly troubleshoot genome editing protocols. Combined with the extensive molecular biology toolbox available for fungi, protocols for editing numerous yeast species have been developed15,16. Such a broad application of genome editing technology in fungi has the potential to significantly impact a wide variety of scientific disciplines.

CRISPR has greatly improved the efficiency of genome engineering in C. albicans, but to date CRISPR has not been used to perform genome wide screens in C. albicans. Current protocols require a repair template to introduce mutations, as the nonhomologous end joining pathway in C. albicans is inefficient12. The generation of repair template oligos for every gene is a significant barrier to the execution of genome-wide screens. The confluence of decreased costs of DNA synthesis and advances to CRISPR technologies will make development of deletion libraries more feasible. For instance, expression of a repair template from the CaCas9 vector paves the way for the development of sustainable plasmid libraries that target every gene11. Furthermore, transient Candida CRISPR protocols that do not require CaCas9 expression vector incorporate into the C. albicans genome have been developed17. In addition, increased guide expression increases genome editing efficiency18. These, and other advances to CRISPR technologies, are crucial to the development of genome-wide screens in C. albicans19,20,21,22.

The C. albicans genome is diploid, but A and B alleles are not always identical5. Such heterozygosity provides both challenges and opportunities. If one aims to target both alleles, a PAM site, guide sequence, and repair template that will act on both copies of the gene must be used. However, depending upon single nucleotide polymorphisms present in a gene, the C.albicans CRISPR system enables investigators to target a single allele. Such precision has the potential to allow investigators to examine functional differences between alleles. Targeting specific alleles must be done carefully, as loss of heterozygosity (LOH) at an allele or of an entire chromosome has been observed. When editing single C. albicans alleles, one must examine adjacent DNA sequences to determine if a clone has maintained a diploid SNP profile. In addition, off-target effects are quite low for C. albicans CRISPR, but whole genome sequencing can be considered for key strains.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Dr. Gennifer Mager for reading and helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by Ball State University laboratory startup funds and NIH-1R15AI130950-01 to D.A.B.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Chemicals | |||

| Agar | BD Bacto | 214010 | |

| agarose | amresco | 0710-500G | |

| Ampicillan | Sigma-Aldrich | A9518 | |

| Bacto Peptone | BD Bacto | 211677 | |

| Bsmb1 | New England Biolabs | R0580L | |

| Calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) | New England Biolabs | M0290L | |

| Cut Smart Buffer | New England Biolabs | B7204S | |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Sigma-Aldrich | D8418 | |

| dNTPs | New England Biolabs | N0447L | |

| Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) | Sigma-Aldrich | 3609 | |

| Glacial Acetic Acid | Sigma-Aldrich | 2810000ACS | |

| Glucose | BDH VWR analytical | BDH9230 | |

| Glycerol | Sigma-Aldrich | 49767 | |

| Kpn1 | New England Biolabs | R3142L | |

| LB-Medium | MP | 3002-032 | |

| Lithium Acetate | Sigma-Aldrich | 517992 | |

| L-Tryptophan | Sigma-Aldrich | T0254 | |

| Maltose | Sigma-Aldrich | M5885 | |

| Molecular Biology Water | Sigma-Aldrich | W4502 | |

| NEB3.1 Buffer | New England Biolabs | B7203S | |

| Nourseothricin | Werner Bioagents | 74667 | |

| Poly(ethylene glycol) PEG 3350 | Sigma-Aldrich | P4338 | |

| Sac1 | New England Biolabs | R3156L | |

| Salmon Sperm DNA | Invitrogen | AM9680 | |

| T4 Polynucleotide kinase | New England Biolabs | M0201S | |

| T4 DNA ligase | New England Biolabs | M0202L | |

| Taq polymerase | New England Biolabs | M0267X | |

| Tris HCl | Sigma-Aldrich | T3253 | |

| uridine | Sigma-Aldrich | U3750 | |

| Yeast Extract | BD Bacto | 212750 | |

| Equipment | |||

| Electrophoresis Appartus | |||

| Incubator | |||

| Microcentifuge | |||

| PCR machine | |||

| Replica Plating Apparatus | |||

| Rollerdrum or shaker | |||

| Spectrophotometer | |||

| Waterbath |

References

- Pfaller, M. A., Diekema, D. J. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clinincal Microbiology Review. 20 (1), 133-163 (2007).

- Magill, S. S., et al. Multistate point-prevalence survey of health care-associated infections. New England Journal of Medicine. 370 (13), 1198-1208 (2014).

- Wisplinghoff, H., et al. Nosocomial bloodstream infections in US hospitals: analysis of 24,179 cases from a prospective nationwide surveillance study. Clinical Infectious Disease. 39 (3), 309-317 (2004).

- Jones, T., et al. The diploid genome sequence of Candida albicans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science USA. 101 (19), 7329-7334 (2004).

- Muzzey, D., Schwartz, K., Weissman, J. S., Sherlock, G. Assembly of a phased diploid Candida albicans genome facilitates allele-specific measurements and provides a simple model for repeat and indel structure. Genome Biology. 14 (9), (2013).

- Morschhauser, J., Michel, S., Staib, P. Sequential gene disruption in Candida albicans by FLP-mediated site-specific recombination. Molecular Microbiololgy. 32 (3), 547-556 (1999).

- Lau, V., Davie, J. R. The discovery and development of the CRISPR system in applications in genome manipulation. Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 95 (2), 203-210 (2017).

- Doudna, J. A., Charpentier, E. Genome editing. The new frontier of genome engineering with CRISPR-Cas9. Science. 346 (6213), 1258096 (2014).

- Anders, C., Niewoehner, O., Duerst, A., Jinek, M. Structural basis of PAM-dependent target DNA recognition by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nature. 513 (7519), 569-573 (2014).

- Reardon, S. Welcome to the CRISPR zoo. Nature. 531 (7593), 160-163 (2016).

- Vyas, V. K., et al. New CRISPR Mutagenesis Strategies Reveal Variation in Repair Mechanisms among Fungi. mSphere. 3 (2), (2018).

- Vyas, V. K., Barrasa, M. I., Fink, G. R. A Candida albicans CRISPR system permits genetic engineering of essential genes and gene families. Science Advances. 1 (3), e1500248 (2015).

- Evans, B. A., et al. Restriction digest screening facilitates efficient detection of site-directed mutations introduced by CRISPR in C. albicans UME6. PeerJ. 6, e4920 (2018).

- Kim, D., et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals specificities of Cpf1 endonucleases in human cells. Nature Biotechnology. 34 (8), 863-868 (2016).

- Tarasava, K., Oh, E. J., Eckert, C. A., Gill, R. T. CRISPR-enabled tools for engineering microbial genomes and phenotypes. Biotechnology Journal. , e1700586 (2018).

- Raschmanova, H., Weninger, A., Glieder, A., Kovar, K., Vogl, T. Implementing CRISPR-Cas technologies in conventional and non-conventional yeasts: Current state and future prospects. Biotechnology Advances. 36 (3), 641-665 (2018).

- Min, K., Ichikawa, Y., Woolford, C. A., Mitchell, A. P. Candida albicans Gene Deletion with a Transient CRISPR-Cas9 System. mSphere. 1 (3), (2016).

- Ng, H., Dean, N. Dramatic Improvement of CRISPR/Cas9 Editing in Candida albicans by Increased Single Guide RNA Expression. mSphere. 2 (2), (2017).

- Huang, M. Y., Woolford, C. A., Mitchell, A. P. Rapid Gene Concatenation for Genetic Rescue of Multigene Mutants in Candida albicans. mSphere. 3 (2), (2018).

- Shapiro, R. S., et al. A CRISPR-Cas9-based gene drive platform for genetic interaction analysis in Candida albicans. Nature Microbiology. 3 (1), 73-82 (2018).

- Grahl, N., Demers, E. G., Crocker, A. W., Hogan, D. A. Use of RNA-Protein Complexes for Genome Editing in Non-albicans Candida Species. mSphere. 2 (3), (2017).

- Nguyen, N., Quail, M. M. F., Hernday, A. D. An Efficient, Rapid, and Recyclable System for CRISPR-Mediated Genome Editing in Candida albicans. mSphere. 2 (2), (2017).

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

ISSN 2578-6326

ABOUT JoVE

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved

We use cookies to enhance your experience on our website.

By continuing to use our website or clicking “Continue”, you are agreeing to accept our cookies.