Involving Individuals with Developmental Language Disorder and Their Parents/Carers in Research Priority Setting

In This Article

Summary

A protocol to enable individuals with developmental language disorder (DLD) and their parents/carers to meaningfully participate in a research priority setting exercise is established. The protocol includes a defined program of activities for data collection, and methods to incorporate this data into the broader research priority setting process.

Abstract

A protocol for involving individuals presenting with developmental language disorder (DLD) (iDLD) and their parents/carers (iDLDPC) in a research priority setting exercise is presented.

iDLD have difficulties with communication skills, such as understanding language, word-finding and discourse. Such difficulties mean existing research priority setting protocols are difficult for iDLD to access, since they require sophisticated communication skills. Thus, a novel protocol for involving iDLD in these exercises is warranted. The same protocol is recommended for use with iDLDPC, to ensure accessibility.

The protocol is presented in 4 steps. Step 1 describes a program of activities delivered by trained, specialist DLD speech and language therapists (SLTs) that prepares iDLD/iDLDPC for involvement. Step 2 outlines an approach to elicit iDLD/iDLDPC’s opinions on research priorities. Steps 3 and 4 describe methods to analyze and integrate this data at multiple stages of the research priority setting process.

9 trained specialist DLD SLTs delivered steps 1 and 2. 17 iDLDs and 25 iDLDPCs consented to involvement. Opinions from all participants were elicited, and this data was used to influence the process and output of the exercise.

An advantage of this protocol is its accommodation of the heterogeneity in support needs of iDLD/iDLDPC, through a menu of options, whilst also providing a structured framework. Due to the novelty of the protocol, the methods for data integration were developed by the research group. These are potential limitations of the protocol, and may bring the reliability and validity under scrutiny, which are yet to be tested.

This protocol enables meaningful involvement of iDLD/iDLDPC in research priority setting and could be utilized for people with other kinds of speech, language or communication needs. Further research should evaluate the effectiveness of the protocol and whether it can be adapted for involvement of such populations in other research studies.

Introduction

Developmental language disorder (DLD) is a multifactorial, life-long condition characterized by difficulties with understanding and/or using language1. This can manifest in any or all areas of speech, language and communication (e.g., understanding instructions, word-finding, or joining a conversation)2. As a result, individuals with DLD (iDLD) are at increased risk of difficulties with their mental health3, relationships4, educational attainment and employment prospects5.

iDLD and their parents/carers (iDLDPC) are supported by speech and language therapists (SLTs) who are required to take an evidence-based approach to practice6. However, many gaps exist in the DLD evidence base7. Research priority setting exercises aim to address such situations, asking key stakeholders to consider what research is most urgently required8. Whilst some research priority setting approaches are focused on gathering 'expert opinion' of researchers9, more recently, and within the UK context, such exercises are more typically carried out in research priority setting partnerships10. Born out of the movement for evidence-based practice11, research priority setting partnerships are designed to address the disconnect between the research agendas of academics, clinicians and users of health services12,13. Bringing together all key stakeholders, including service-users, to jointly decide upon research priorities offers theoretical and pragmatic benefits, improving the relevance, quality and impact of the process14. Additionally, involving service-users in research priority setting is a public and patient involvement (PPI) imperative within the UK's National Health Service15. It is therefore crucial that iDLD/iDLDPC are involved in research priority setting in this area.

There is no “gold standard method for health research … priority setting”14 but several approaches have been published. However, the communication challenges faced by iDLD/iDLDPC put them (or their opinions) at risk of being excluded via these methods. For example, the Dialogue Model relies entirely on in depth interviews with service-users16. Similarly, the James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership (JLA PSP) approach17, which upholds itself on inclusion of all patient voices, would still present challenges for iDLD. The JLA PSP methodology utilizes Nominal Group Technique, requiring participants to independently ‘brainstorm’ ideas, verbally express and then discuss them18. It is reasonable to assume the extent of meaningful involvement of iDLD/iDLDPC may be limited when using these approaches to research priority setting.

Another challenge in involving iDLD/iDLDPC in standardized protocols is that even if support was available, each individual will present a unique combination of strengths and needs in different aspects of language and communication1. Thus, one approach is unlikely to address the needs of everyone, putting some individuals at risk of exclusion. Here, a novel methodology is presented that embeds differentiated instruction and flexibility at its center. Perceived to be integral to the protocol is its delivery by specialist DLD SLTs with a detailed understanding of the iDLD/iDLDPC’s specific communication skills. This enhances reliability and assures quality as the SLT has: specialist knowledge, skills and experience working in DLD, and has already built a therapeutic relationship with the iDLD/iDLDPC19. This increases both the likelihood that the SLT can identify when the iDLD has understood and that the SLT can interpret the iDLD opinions accurately.

Resources and time are frequently cited as barriers to meaningful involvement of service-users in research20. Individuals with complex needs may be particularly disadvantaged. The British Academy of Childhood Disability state about their JLA PSP21: “our resources and time were insufficient to engage children and young people meaningfully” but that meaningful involvement could have been greater with “adequate resources” and “careful planning”. Pollock, St George, Fenton, Crowe & Firkins22 adapted the JLA protocol in order to account for this additional demand on capacity and resources. Their ‘FREE TEA’ model was implemented in a PSP for life after stroke. This offered an alternative, face-to-face method to yield data from service-users, which was considered to be much richer than that obtained through surveys. Additionally, Rowbotham et al.10 demonstrated success of online participation, which was imperative for the healthy involvement of people with cystic fibrosis (CF), in a CF JLA PSP. These innovative approaches demonstrate that when resources and time are used strategically, meaningful involvement is bolstered and the final output more reflective of service-user priorities.

It is well documented in the PPI literature that tokenism is common, which risks trivializing the impact and value of PPI20. This protocol describes a four-step process for meaningful involvement of iDLD/iDLDPC in a research priority setting exercise at multiple stages, reducing risk of tokenism:

Step 1: A program of activities for SLTs to carry out with iDLDs/iDLDPCs, aimed at developing their understanding of concepts related to research priorities;

Step 2: An exercise for data collection on research priorities;

Step 3: A method for data transformation to influence early stages of a research priority setting process;

Step 4: A method for data transformation to influence late stages of a research priority setting process

To administer steps one and two, SLTs were recruited via advertisement in the organization’s general communications (for example, online forums). SLTs were required to be specialist DLD SLTs of UK band 6 (or above), and who had iDLD/iDLDPC on their caseload who they were familiar with and who could consent to participating. SLTs attended a 3 hour training session delivered by the research group (KC, AK, LL) to become familiar with the theoretical approach to the project, the program of activities and materials used. To maximize generalizability of the protocol, minimal exclusion criteria were specified for iDLD/iDLDPC participants. The expert SLTs formed consensus on the criteria that children in Key Stage 2 or above (7 years +) would be involved and would also allow iDLD with either suspected or confirmed DLD to participate. Selection of participants relied on the SLT’s clinical judgement of whether the iDLD/iDLDPC would be able to access the activities, even if suitable according to the inclusion criteria.

The program of activities, described in step 1 of the protocol uses an evidence-based inclusive communication approach, using tools and strategies to help iDLD understand and express themselves. Needs were planned for rather than reacted to and inclusive communication strategies were integrated consistently across the priority setting exercise, for example in forms, online communications and materials23. Activities were developed based upon the triangle of accessible support24, and addressed individual strengths and needs of the iDLD. The program includes optional activities and ones that can be implemented in different formats, which are to be selected by the specialist DLD SLT to tailor to the needs of iDLD/iDLDPC. This further recognizes the unique clinical skills, knowledge and experience of the SLT which optimize the iDLD’s communication capacity24. This component of the protocol is supported by materials found in the Supplementary Files.

The data collection activity described in step 2 of the protocol was based on 11 ‘topics’ about DLD, which were associated with superordinate themes identified from a previous evaluation of professionals’ ‘uncertainties’ about DLD research25. iDLD/iDLDPC may experience greater difficulty with verbal reasoning26 therefore a topic-based approach was chosen over the presentation of many subordinate topics. Working memory may also be impaired in iDLD/iDLDPC27, thus in order to support iDLD/iDLDPC with decision-making, data was obtained via an individual-topic rating exercise followed by a comparative ranking exercise when appropriate.

Step 3 presents a data transformation process enabling iDLD/iDLDPC’s opinions on priorities to influence the early research priority setting process, by determining the types of topics that other stakeholders should discuss in the initial stages of the process. This was achieved by examining the average ratings by iDLD/iDLDPC’s on their perceived level of ‘priority’ of the 11 DLD research topics (obtained from step 2) and forming consensus on whether there was sufficient agreement from participants on highly-rated (i.e., ‘prioritized’) topics. The aim of this evaluation was to inform which, if any, topics could be validly disregarded and not considered in the subsequent stages of the process, and which should be taken forward.

The final step describes use of the same data to transform survey data to further reflect iDLD/iDLDPC’s priorities and influence the final output. As part of the broader research priority setting process (beyond this protocol), defined research areas for DLD were developed by stakeholders, who subsequently voted for which areas they considered a priority via an online survey. Each defined research area was related to one of more of the topics that were previously rated by iDLD/iDLDPC. The iDLD/iDLDPC rating data was used to ‘boost’ votes for the defined research areas associated with highly rated research topics.

This protocol is designed for those planning to set research priorities for DLD, who wish to meaningfully involve iDLD/iDLDPC. Access to specialist DLD SLTs and their clinical caseload of iDLD, and iDLDPC is required. It is designed to complement an overall research priority setting process collecting additional data, for example the topics of interest and defined research areas. A project group approach is recommended to allow for group decision-making. It may also be adaptable for use with iDLD/iDLDPC or different populations with speech, language and communication disorders, in other research activities.

Protocol

This protocol is designed to be carried out with human participants. Advice on ethical approval was sought by the research group from the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) and James Lind Alliance (JLA). Both state that research priority setting is “seen as service evaluation and development”17 and therefore does not require ethical approval.

1. Step 1: Deliver the program of activities to iDLD/iDLDPC

- As the estimated time of execution varies, carry out the activities as standalone activities (but should be sequential) delivered at different times, or delivered as a continuous program (approximately 90 minutes in total). Estimated standalone times are provided in each step, though exact timings will depend on the iDLD/iDLDPC’s ability to access material and the level of support that is required from the specialist DLD SLT.

NOTE: The decision to deliver the activities as standalone activities or a continuous program is to be made by the specialist DLD SLT, using clinical judgement to inform decisions based on in depth knowledge of specific speech, language and communication needs of iDLD/iDLDPC. iDLD/iDLDPC with well-developed attention and listening skills may be able to engage with several activities or a continuous program at one time. iDLD/iDLDPC with lower levels of attention and listening skills may be best suited to one or two standalone activities at one time. - Throughout the protocol, the specialist DLD SLT is instructed to use communication supports ‘as appropriate’. These supports are not defined, but should be selected and provided at the discretion of the specialist DLD SLT and will be unique to the needs of each iDLD/iDLDPC.

- Have the specialist DLD SLT choose the appropriate setting to deliver the program of activities using clinical judgement per iDLD/iDLDPC (10 minutes per iDLD/iDLDPC).

- Have the specialist DLD SLT revise in depth knowledge of the specific speech, language and communication needs of iDLD/iDLDPC they may invite to participate.

- Have the specialist DLD SLT consider the level of communication support that would be required for iDLD/iDLDPC.

- Have the specialist DLD SLT decide which iDLD/iDLDPC they will invite to participate who require substantial one-to-one support and plan for delivery in one-to-one setting.

- Have the specialist DLD SLT decide which iDLD/iDLDPC they will invite to participate who do not require one-to-one support and who benefit from peer support and interaction, and plan for delivery in a group setting.

NOTE: The subsequent steps of the protocol can be used in either setting.

- Introduce participant(s) to each other, as appropriate, and introduce the purpose of session to facilitate rapport building. Use communication supports as appropriate throughout (10 minutes).

- Introduce self to iDLD/iDLDPC as appropriate: “My name is xxx”.

- Encourage iDLD/iDLDPC to introduce selves as appropriate, in turn: “Now it’s your turn, what is your name?”.

- Introduce broad aim of session to iDLD/iDLDPC: “Today we are going to talk about the most important things you want to know more about, about communication”.

- Inform the iDLD/iDLDPC on the outline of the session using Supplementary File A: “First we will talk about if you want to join in, or not- it’s up to you. Then, we will do some games, and activities.”

- Talk through the project information booklet Supplementary File B with iDLD/iDLDPC.

- Obtain informed consent from iDLD/iDLDPC for participation in the session. Use communication supports as appropriate throughout (10 minutes).

- Inform iDLD/iDLDPC that they can decide whether to take part: “Do you want to talk to me about this?”; “You can choose to join in today or you can choose to not join in. It’s up to you”; “If you don’t want to, that is okay.”

- Talk through each item on the consent form (Supplementary File C for iDLDPC, or Supplementary File D for iDLD (or iDLDPC if appropriate) with iDLD/iDLDPC.

- Review and consolidate iDLD/iDLDPC understanding of the session, their rights, and ability to consent by asking questions: “Tell me about what we’re doing today?”; “Do you have any questions?”

- Support iDLD/iDLDPC to sign a consent form if consent is given. For iDLD, obtain prior consent from iDLDPC for their child’s participation. If consent is not given, iDLD/iDLDPC chooses to either participate but their data goes unrecorded; or can cease participation.

- Consolidate and teach key concept of ‘speech, language and communication’. Use communication supports as appropriate throughout (10 minutes).

- Inform iDLD/iDLDPC on the focus of this activity: “The next activity will be focused on speech, language and communication”

- Facilitate discussion on the question: what ‘is’ speech/language/communication? Using SLT expertise & knowledge of participants' needs and motivators, have the SLT select either game format (step 1.6.3) or discussion format (step 1.6.4). Use Supplementary File E as appropriate.

- Game format: Ask iDLD/iDLDPC to pass around a rewarding object (for example, a flashing ball) in turn and explain: “When you are holding the [object] you can tell us something about speech, language or communication”.

- Discussion format: Ask iDLD/iDLDPC: “What do you think the words ‘speech’, ‘language’ or ‘communication’ mean?”

- Provide iDLD/iDLDPC with additional ideas: “talking is communication”; “signing is communication”; “How else do we ‘communicate’?”; “Can you communicate without talking?” or “What are other ways of telling someone how we feel?”

- Consolidate and teach key concept of ‘developmental language disorder or speech/language/communication difficulties’. Use communication supports as appropriate throughout (10 minutes).

- Inform iDLD/iDLDPC on the focus of this activity (using appropriate terminology as decided by specialist DLD SLT based their personal historic use of terms with iDLD/iDLDPC): “In the next activity we will think about things we find difficult about speech/language/communication/ DLD/ things that you might find difficult because of DLD.”

- Facilitate discussion on the question: what ‘is’ speech/language/communication or DLD? Using SLT expertise & knowledge of participants' needs and motivators, have SLT select either game format (step 1.7.3) or discussion format (step 1.7.4). Use Supplementary File E as appropriate.

- Game format: Ask iDLD/iDLDPC to pass around a rewarding object (e.g., flashing ball) in turn and explain: “When you are holding the [object] you can tell us something about speech, language or communication that someone might find hard/ difficult because of DLD”.

- Discussion format: Ask iDLD/iDLDPC: “What do you think some people might find hard about speech, language or communication?”

- Provide iDLD/iDLDPC with additional ideas and describe using communication supports as appropriate: “Some people find it hard to remember words”; “Some people find it hard to put words in the right order”; “Some people find it hard to talk to people they don’t know very well”.

- OPTIONAL: Have SLT facilitate reflection on their experiences of difficulties with speech, language and communication: “What do you find hard about communication?”

- Consolidate and teach key concept of ‘speech and language therapy’. Use communication supports as appropriate (10 minutes).

- Inform iDLD/iDLDPC on the focus of this activity: “The next activity will be focused on describing what speech and language therapy is.”

- Facilitate discussion on the question: what ‘is’ speech and language therapy? Using SLT expertise & knowledge of participants' needs and motivators, SLT to select either game format (step 1.8.3) or discussion format (step 1.8.4). Use Supplementary File E as appropriate.

- Game format: Ask iDLD/iDLDPC to pass around a rewarding object (e.g., flashing ball) in turn and explain: “When you are holding the [object] you can tell us something about speech and language therapy”.

- Discussion format: Ask iDLD/iDLDPC what they understand by the terms speech and language therapist/therapy.

- Provide iDLD/iDLDPC with additional ideas and describe: “Your speech and language therapist might help you with your talking”; “Speech and language therapy might help you learn new words in school”.

- OPTIONAL: If appropriate, have SLT facilitate reflection on their experiences of a speech and language therapist/therapy: “What do you like about speech and language therapy?”; “What do you not like about speech and language therapy?”; “What would you change about speech and language therapy”

- OPTIONAL: If appropriate, have SLT ask iDLD/iDLDPC: “How do you know if your speech and language therapy is helping?”

- Consolidate and teach key concept of ‘research’. Use communication supports as appropriate throughout (10 minutes).

- Inform iDLD/iDLDPC on the focus of this activity: “In the next activity we will learn about the word ‘research’”.

- Facilitate discussion on the question: ‘What does research mean?’. Use Supplementary File F as appropriate.

- Describe what is meant by ‘research’ to iDLD/iDLDPC at appropriate level of detail: “Research helps us answer questions.”; “Research is work that helps us find out things.”; “Research is the process of trying to find answers to questions, and doing this in a clear, organised, scientific way”. Use Supplementary File F as appropriate.

- Have SLT optionally select one or more of activities (steps 1.9.5, steps 1.9.6) as appropriate for the needs of iDLD/iDLDPC.

- Present newspaper template Supplementary File G to iDLD/iDLDPC to facilitate explanation of ‘research’: “We are told about research in the news.”; “Newspapers often tell us about research”; “We find out about new research in the news.”

- Present examples of headlines about research Supplementary File H to iDLD/iDLDPC to facilitate explanation of ‘research’: “Here’s some research- ‘Scientists discover a cure for cancer’”; “Here is the headline ‘Researchers find out how dogs can do your shopping for you’- is this research?”; “How about ‘Researchers discover shoes that tie themselves’. Would this be research?”.

- Explain to iDLD/iDLDPC the main focus of the session: “So today we will be thinking about research that tells us about DLD/speech and language difficulties.” Use Supplementary File E and Supplementary File H in combination, if appropriate.

- Consolidate and teach the key concept of ‘priority’. Use communication supports as appropriate throughout (10 minutes).

- Inform iDLD/iDLDPC on the focus of this activity: “Now we will be thinking about what a ‘priority’ is”

- Facilitate discussion on the question: “What does it mean if something is a ‘priority’?”. Use Supplementary File I as appropriate.

- SLT to optionally select one or more of supporting activities (steps 1.10.4-1.10.7) as appropriate.

- Describe what is meant by ‘priority’ to iDLD/iDLDPC at appropriate level of detail: “A priority is something that is really, really important to you. Something that is not a priority is something that is not important to you.” Use Supplementary File I as appropriate.

- Present iDLD/iDLDPC with Supplementary File J as stimuli to evoke decision-making on what is a priority/ what is important to the iDLD/iDLD. Ask iDLD/iDLDPC to think about each activity depicted in Supplementary File J. Ask iDLD/iDLDPC: “Is doing [activity] a priority for you?”.

- Ask iDLD/iDLDPC and facilitate discussion on the question: “What are your priorities in your life?”

- Facilitate discussion on the question: what does it mean to be a ‘research priority’? Use communication supports as appropriate throughout (10 minutes).

NOTE: SLT may deliver all, or part of, these steps depending on iDLD/iDLDPC level of understanding, to be decided by SLT using clinical expertise, and presented as appropriate.- Inform iDLD/iDLDPC on the focus of this activity: “Now we know about research, and we know about priorities. Next, we will think about what ‘research priority’ means. There are different kinds of research and people will have different priorities for research.” Use Supplementary File F and Supplementary File G as appropriate, to remind iDLD/iDLDPC of previous activities.

- Ask iDLD/iDLDPC: “Do you think any of these headlines are a research priority?” Use Supplementary File F, G & H as appropriate.

- Ask iDLD/iDLDPC to think about their research priorities: “What would you like to find out about the most, through research?”; “What are your research priorities? This could be to do with your favorite hobbies, school, the food you eat, or your health?”; “Is there something that you think should be researched more?” Use Supplementary File F, G, H, & I as appropriate.

- Explain to iDLD/iDLDPC: “The next focus of the session is about research priorities for speech and language therapy.”

2. Step 2: Specialist DLD SLT to collect data on iDLD/iDLDPC’s research priorities for DLD

- Carry out rating activity with iDLD/iDLDPC to identify research priorities. The topics referred to in this step are identified in earlier stages of the research priority setting exercise, outside the scope of this protocol. Use communication supports as appropriate throughout.

- Inform iDLD/iDLDPC on the focus of this activity: “In the next activity we will think all about which areas of speech and language therapy that you think are most important for us to know more about”

- Present the topics (Identification, assessment, bilingualism, intervention, service delivery- primary school, service delivery- secondary school, service delivery- adult, lifelong impact, technology, working with others, raising awareness) to iDLD/iDLDPC using topic cards (in Supplementary File K) in turn.

- Explain each topic to iDLD/iDLDPC, using Supplementary File K to facilitate understanding when deemed necessary by the SLT: “The first topic is how we might find out whether someone finds speech, language or communication hard.”; “The next topic is using things like computers or tablets in speech and language therapy”.

- To support understanding further, if SLT deems appropriate then refer to Supplementary File L, to help describe them: “Let’s think about what else ‘Identification’ might mean. It could be about finding out about someone who is finding school difficult … or misbehaving in class …”

- Present iDLD/iDLDPC with the scale Supplementary File I and explain: “These numbers can be used to show how ‘important’ or how much of a ‘priority’ something is.”

- Present iDLD/iDLDPC with individual topic cards Supplementary File K in turn and ask for their opinion: “How important do you think it is to find out more about [topic]? Would it be at the top- really important/a priority; or nearer the bottom- not important/not a priority.”

- Support iDLD/iDLDPC to place topic cards (Supplementary File K) along the scale (Supplementary File I) appropriately given their responses to step 2.6, and facilitate decision-making using verbal prompts: “So ‘assessment’ is more important than ‘technology’. Is that right?”.

- Continue to verify and confirm until all topics are placed.

- Once all topics are rated by iDLD/iDLDPC, feedback and confirm their decisions by talking through the ratings of each topic. Provide an opportunity for them to make any changes, highlighting and confirming strong priorities/not priorities if evident: “You’ve said the most important topic to find out more about is [topic]. You’ve said the least important topic to find out more about is [topic]. Do you think that’s right?”

- Present iDLD with a certificate of participation (Supplementary Material M) and record their data.

3. Step 3: Transform the data from iDLD/iDLDPC to influence early stages of research priority setting exercise

- Use iDLD/iDLDPC prioritisation data to inform on the topics which are to be discussed by other stakeholders in the next stage of the research priority setting exercise.

- Collate all topic ratings from a sample of iDLD/iDLD and calculate the median rating of each topic, and the range of medians across all topics.

- Order topic medians by size and present on a bar chart to visually inspect for whether there are any clearly prioritized topics, which have medians substantially higher than non-prioritized topics. For example, a considerable difference in median at some interval between topics.

- Consider findings from step 3.3 alongside the range of medians to help interpret data. For example, a range of less than 6 could imply a clustering of similarly-rated topics which may indicate there is no clear prioritization. Larger ranges could imply greater differentiation of priority and non-priority topics.

- Have the research group use knowledge from steps 3.3 and 3.4 to identify if a cut-off value can be determined in which any topic with a median value above that cut off will be carried forward to future steps of the research priority setting exercise. If no cut-off can be identified, all topics should be carried forward.

4. Step 4: Transform the data from iDLD/iDLDPC to influence final stages of research priority setting exercise

NOTE: Results from the research priority setting survey of defined research areas are identified in an interim stage of the research priority setting exercise, outside the scope of this protocol.

- Combine research priority setting survey data of defined research areas with iDLD/iDLDPC rating data to identify the top ten research priorities.

- Examine the spread of individual topic ratings from iDLD/iDLDPC to identify whether there is an appropriate cut-off point which can represent a numerical boundary distinguishing ‘priority’ and ‘not-priority’ topics, in concordance with the survey data. The cut-off value will depend on the researcher’s interpretation of their own data and may be different in other instances: a rating of less than 8 reflects ‘not a priority’ and above a rating of 8 reflects ‘a priority’.

- Calculate the frequency with which each topic was rated by iDLD/iDLDPC above the cut-off point (i.e., how many times it was considered a priority). This frequency is the ‘corrector value’.

- Assign defined research areas to one or more of the topics (but ≤3). Assigned topics represent the broad areas which are covered within that defined research area. For example, a defined research area about ‘intervention via tele-therapy for primary school age children’ may be assigned to the following topics: intervention, service delivery – primary, and technology.

- Add the corrector values for each defined research area (which may be more than one, dependent on how many topics the research area is related to) to the survey data.

- Sort the combined data (which now includes survey data and corrector values) for each defined research area by size. The ten highest scoring areas are the top ten research priorities.

Representative Results

Nine speech and language therapists were trained to deliver step one and two of the protocol and carried it out with 17 iDLD (between Key stage 2 and Key stage 4, 7-16 years) and 25 iDLDPC (total n=42). All 42 participants were able to engage in the session. This was evidenced by all 42 participants being able to provide ratings, considered by the SLT to reflect their views on research priorities for DLD, as per step two of the protocol.

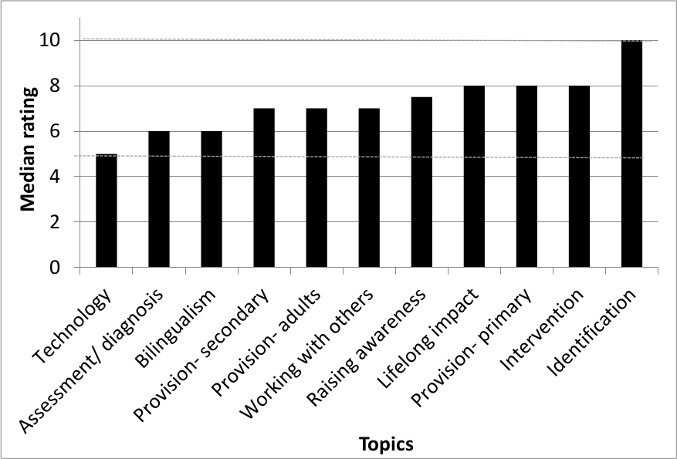

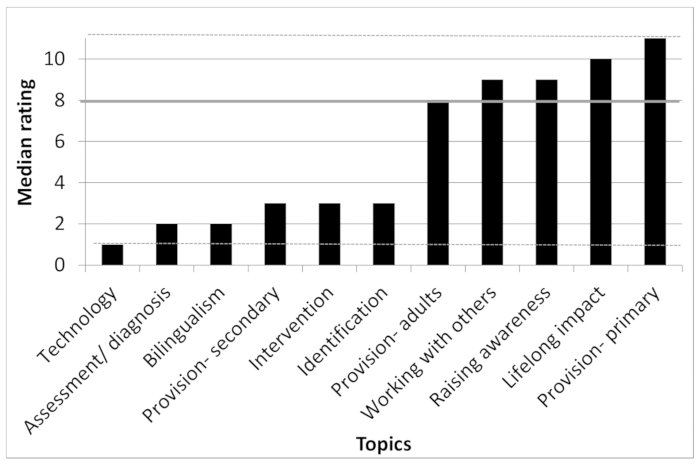

The data obtained in the sessions was successfully used to influence the next stage in the research priority setting exercise, as described in step three. The range was small (5) and no clear delineation of priority topics was evident in this exercise (Figure 1) therefore all 11 topics were taken to the next stage. An example of a fictional alternative scenario is presented in Figure 2.

Corrector values were calculated for each defined research area based on the iDLD/iDLDPC data (Table 1) and applied to the survey data (Table 2). The data transformation had a substantial impact on the final output (Table 3). This included:

- The omission of one defined research area from the top ten

- The introduction of one defined research area into the top ten

- The alteration of the overall ranking of defined research areas

Figure 1: Graph to show median topic ratings from iDLD/iDLDPC. Note the absence of distinct preference, further demonstrated by a small range highlighted by dashed lines (5-10). No cut-off identified, all topics carried to the next stage. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Graph to show fictional median topic ratings of iDLD/iDLDPC. This illustrates an alternative spread of data with more distinct preferences, demonstrated by a large range highlighted by dashed lines (1-11). A suggested cut-off is shown by the solid line at median=8. Topics with median rating ≥ 8 carried to the next stage. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Supplementary Files. Please click here to download these files.

| Participant (n=42) | Topic Rating | ||||||||||

| Identification | Assessment/ diagnosis | Bilingualism | Lifelong impact | Provision- primary | Provision- secondary | Provision- adults | Intervention | Working with others | Raising awareness | Technology | |

| 1 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 8 | |||

| 2 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 10 | |||

| 3 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 9 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 7 | 5 | 11 | 3 |

| 4 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 11 | 9 | 3 | 2 | 10 | 5 | 6 | 4 |

| 5 | 7 | 11 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 1 |

| 6 | 10 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 11 | 1 |

| 7 | 1 | 2 | 10 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 3 | 8 | 11 |

| 8 | 10 | 1 | 6 | 11 | 2 | 7 | 9 | 5 | 8 | 4 | 3 |

| 9 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 10 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 8 |

| 10 | 1 | 4 | 11 | 10 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 2 | 8 | 5 | 7 |

| 11 | 1 | 2 | 11 | 8 | 3 | 9 | 10 | 4 | 6 | 5 | 7 |

| 12 | 10 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 9 | 11 | 8 | 5 | 4 |

| 13 | 2 | 3 | 11 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 8 | 10 | 5 | 9 | 1 |

| 14 | 2 | 5 | 9 | 11 | 10 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 8 | 5 |

| 15 | 6 | 3 | 5 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 8 | 4 | 2 | ||

| 16 | 10 | 8 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 | 1 | |

| 17 | 11 | 9 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 6 | 1 | 8 | 10 | 4 | 5 |

| 18 | 8 | 9 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 10 | |

| 19 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| 20 | 10 | 10 | 1 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 7 |

| 21 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 7 | 6 | 1 | 9 | 6 | 8 | 6 | |

| 22 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 5 | |||||

| 23 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 5 | 10 | ||||||

| 24 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | ||||

| 25 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 6 | 9 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 10 | 8 |

| 26 | 10 | 9 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | |

| 27 | 10 | 9 | 2 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 8 | 7 | 1 | |

| 28 | 10 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 9 | 6 | 7 | |

| 29 | 10 | 6 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 9 | 8 | 1 | |

| 30 | 10 | 2 | 1 | 9 | 8 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 6 | |

| 31 | 10 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 8 | 9 |

| 32 | 8 | 7 | 1 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 5 |

| 33 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 8 | 10 | 7 | 10 | 8 | 9 | 5 |

| 34 | 9 | 10 | 6 | 8 | 10 | 1 | 7 | 10 | 4 | 10 | 10 |

| 35 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 10 | 9 | 7 | 5 | 10 | 1 | 10 | 1 |

| 36 | 11 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 11 | 8 | 6 |

| 37 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| 38 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 10 | 5 | ||

| 39 | 10 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 6 | 10 | 10 | ||

| 40 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 6 | 6 | 9 | ||

| 41 | 8 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 1 | ||

| 42 | 8 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 8 | ||

| Corrector value | 26 | 16 | 14 | 24 | 23 | 15 | 15 | 24 | 13 | 20 | 12 |

Table 1: Topic ratings from all iDLD/iDLDPC participants with corrector values. Corrector value = frequency of topic rated above 7 (identified as cut-off). Corrector values transform survey data to integrate iDLD/iDLDPC data. Ratings above cut-off are in bold-italic. Blank spaces indicate topics not discussed or rated by iDLD/iDLDPC.

| Research topic | Survey score | Topic Corrector Values | Final score | ||||

| Specific characteristics of evidence-based DLD interventions which facilitate progress towards the goals of an individual with DLD | 462 | Intervention | 486 | ||||

| 24 | |||||||

| Effective tools to assist accurate diagnosis of DLD in early years children with significant SLCN | 418 | Assessment/diagnosis | 434 | ||||

| 16 | |||||||

| Implementation of SLT recommendations in the classroom by teaching staff: confidence levels, capacity, capability and levels of success | 441 | Working with others | 454 | ||||

| 13 | |||||||

| Effective ways of teaching self-help strategies to children with DLD | 414 | Intervention | 438 | ||||

| 24 | |||||||

| Effective interventions for improving receptive language in terms of intervention characteristics and mode of delivery | 434 | Intervention | 458 | ||||

| 24 | |||||||

| Impact of including speech, language and communication needs (SLCN)/ developmental language disorder (DLD) in teacher training course curriculums on referral rates and level of support for children with DLD | 409 | Working with others | Identification | 448 | |||

| 13 | 26 | ||||||

| Effectiveness of a face-to-face versus indirect approach to intervention for individuals with DLD | 417 | Provision- primary | Provision- secondary | Provision- adult | 470 | ||

| 23 | 15 | 15 | |||||

| Outcomes for individuals with DLD across settings (e.g. language provision, mainstream school), in relation to curriculum access, language development and social skills | 415 | Lifelong impact | Provision- primary | Provision- secondary | 477 | ||

| 24 | 23 | 15 | |||||

| Impact of SLT interventions for adolescents and adults with DLD, on wider functional outcomes (e.g. quality of life, access to the curriculum, social inclusion and mental health) | 392 | Lifelong impact | Intervention | 440 | |||

| 24 | 24 | ||||||

| Impact of targeted vocabulary interventions for individuals with DLD on curriculum access | 410 | Intervention | 434 | ||||

| 24 | |||||||

Table 2: Top ten research topics from survey with unadjusted scores, with application of corrector values and adjusted scores. Each defined research area is assigned to one or more topic, and adjusted proportionately. The final column indicates final score which is used to identify top ten highest scoring research priorities

| Rank | Unadjusted top ten research priorities (Correctors not applied, survey data only) | Adjusted top ten research priorities (Corrector values applied) | ||||

| 1 | Specific characteristics of evidence-based DLD interventions which facilitate progress towards the goals of an individual with DLD | Outcomes for individuals with DLD across settings (e.g. language provision, mainstream school), in relation to curriculum access, language development and social skills | ||||

| 2 | Effective tools to assist accurate diagnosis of DLD in early years children with significant SLCN* | Specific characteristics of evidence-based DLD interventions which facilitate progress towards the goals of an individual with DLD | ||||

| 3 | Implementation of SLT recommendations in the classroom by teaching staff: confidence levels, capacity, capability and levels of success | Effectiveness of a face-to-face versus indirect approach to intervention for individuals with DLD | ||||

| 4 | Effective ways of teaching self-help strategies to children with DLD | Effective interventions for improving receptive language in terms of intervention characteristics and mode of delivery | ||||

| 5 | Effective interventions for improving receptive language in terms of intervention characteristics and mode of delivery (402) | Impact of including speech, language and communication needs (SLCN)/ developmental language disorder (DLD) in teacher training course curriculums on referral rates and level of support for children with DLD | ||||

| 6 | Impact of including speech, language and communication needs (SLCN)/ developmental language disorder (DLD) in teacher training course curriculums on referral rates and level of support for children with DLD | Impact of SLT interventions for adolescents and adults with DLD, on wider functional outcomes (e.g. quality of life, access to the curriculum, social inclusion and mental health)* | ||||

| 7 | Effectiveness of a face-to-face versus indirect approach to intervention for individuals with DLD | Implementation of SLT recommendations in the classroom by teaching staff: confidence levels, capacity, capability and levels of success | ||||

| 8 | Outcomes for individuals with DLD across settings (e.g. language provision, mainstream school), in relation to curriculum access, language development and social skills | Effective ways of teaching self-help strategies to children with DLD | ||||

| 9 | Impact of SLT interventions for adolescents and adults with DLD, on wider functional outcomes (e.g. quality of life, access to the curriculum, social inclusion and mental health) | Impact of targeted vocabulary interventions for individuals with DLD on curriculum access | ||||

| 10 | Impact of targeted vocabulary interventions for individuals with DLD on curriculum access | Impact of teacher training (on specific strategies/ language support) on academic attainment in adolescents with DLD in secondary schools | ||||

Table 3: Unadjusted and adjusted top ten research priorities lists. Table to show the top ten research priorities without adjustment (left column) and with adjustment (right column). * depict defined research areas which are not represented in the top ten of the other columns (i.e., where priorities were different).

Discussion

The protocol presented here reflects an experimental, novel approach to incorporating the views of iDLD/iDLDPC into a research priority setting exercise. In its development, it was considered that an important aspect of the protocol is the execution of Step 1 and 2 by a SLT with specialist skills in DLD, and who understands the individualized support needs of iDLD/iDLDPC. This aimed to support validity of the outputs, which subsequently influenced the next stages of the research priority setting process. The protocol directs execution of evidence-based support strategies for iDLD, which are aimed at priming the skills and understanding required for their full participation in the exercise. Moreover, the steps in the protocol can be modified, by the SLT, to the most suitable level for each individual. As experts in speech, language and communication needs, the role of the SLT in these steps is important to ensure the iDLD/iDLDPC has understood the concepts and can consequently express their opinion about them. Whilst the SLTs were required to be: (a) a DLD specialist and (b) familiar with the iDLD/iDLDPC, the impact of these requisites was not evaluated and so it is possible that these could be modified in future replications of the protocol. Nevertheless, such demand of expertise, resource and capacity is unlikely to be supplied in standard research priority setting protocols and it is valuable to explore solutions.

Presentation of this protocol may assist future projects in planning for and incorporating service-user input into their research priority setting. However, it is recognized that the protocol is likely to evolve; following a pilot of the protocol, some modifications were made. This largely included further refinement of the program of activities in Step 1. For example, in the pilot protocol, step 1.6 Consolidate and teach key concept of ‘speech, language and communication’ was essentially omitted, but it was found that additional time needed to be spent consolidating these concepts for some iDLD/iDLDPC, therefore an activity was added in. It was also identified that adding in this step could have additional benefits for the iDLD/iDLDPC, since DLD is a relatively new diagnosis2. Participation may therefore offer iDLD/iDLDPC a unique opportunity to learn more about their diagnosis and what this means for them and others, in a world where there is limited diagnostic adjustment work or psychosocial support available28. It is likely that there may be other creative modifications that may enhance either the experience of participating for iDLD/iDLDPC, or the validity of the outputs. We anticipate that future iterations of the protocol could involve a greater focus on preparatory activities to ensure understanding of key concepts such as 'research' and 'priorities', especially for younger iDLD. Reflections from carrying out the sessions with iDLD/iDLDPC suggested that some of the materials developed for this section (for example, Supplementary File H) caused a level of confusion and could be developed further, by changing the phrasing of the ‘research headlines’ to be more fit-for-purpose.

While the aim was to develop an evidence-based protocol, there were challenges in doing so for some aspects. This applies to, for example, identifying a meaningful way to transform ratings of topics by iDLD/iDLDPC into the defined research area survey data. This necessitates a degree of pragmatism and judgement resulting from the absence of an accepted, robust approach. It is recognized that some elements of the protocol rely on consensus of the research group. This aligns with the approach taken in other methods, notably, the JLA PSPs17. While only small-scale in this protocol, consensus-making is a method which carries flaws in and of itself29. Going forward, it is possible a more reliable, valid and stringent way of transforming this data could be identified. Additionally, it is difficult to truly secure the fidelity of the protocol describing the program of activities. Supporting communication in iDLD should be personalized for the individual’s unique combination of strengths and needs2 and so given the heterogeneity of the population of iDLD, the protocol is likely to require ongoing adaptation.

While it is perceived that the protocol’s accommodation of individual needs is advantageous and suggests the protocol could be carried out with iDLD aged 7 years and above, it is acknowledged that in the context of traditional scientific rigor employing different approaches with different participants would be seen to compromise the reliability of the results. It is also difficult to ascertain the true extent to which iDLD/iDLDPC were able to access the exercise, and to which their ratings are valid and reliable. For some iDLD/iDLDPC, particularly those who are young or who have only recently learned about their diagnosis of DLD, obtaining a clear understanding of what this means for them presents a considerable challenge. A number of steps were taken to minimize these risks, such as repetition and consolidation activities. In future, measures could be taken to capture and evaluate this robustly: assessing the SLT’s confidence in each iDLD/iDLDPC’s understanding and authenticity of the ratings, or carrying out the protocol on a different day with the same iDLD/iDLDPC and comparing findings. Furthermore, the iDLDs that ended up participating were school-aged children, therefore while the protocol’s success may suggest it is useful for this age group, it may not be appropriate to generalize to adults with DLD. Future examination of this would be of interest.

While there is an increasing focus on inclusion of groups of individuals requiring different types and levels of support to access research involvement30 the extent to which adaptations are made for individuals with speech, language or communication needs is questionable. While PPI guidance tends to highlight the need for clear communication with patient groups (e.g., the UK PI Standards31) this is often oriented to ensuring the style of information or terminology given by professionals or researchers is accessible to the ‘layperson’. There is a fundamental gap in the guidance on how to create PPI protocols which are accessible to those who have communication difficulties. Some research proposes methods for engaging such populations in, for example, qualitative research32 that provides a useful backdrop to the methods presented here. However, it is possible research priority setting exercises present a unique challenge for people with communication difficulties given the abstract and metacognitive concepts of ‘research’ and ‘research priorities’. This protocol describes one process which could be taken to address these challenges.

Whilst iDLD were presented a certificate of participation, iDLD and iDLDPC were not financially rewarded for their involvement in this protocol, contrary to good practice33. This was because the budget for such payment was not fully appreciated when the project was first conceived. Since this point, in 2014, a body of evidence has emerged further refining the role of patients and public in research34, particularly implementation research35, and the cost and consequences of PPI36. These include recommendations pertaining to the use of rewards, including financially incentivizing service-users which aims to also reduce power differentials and empower individuals, and demonstrate the value that researchers place on their time, commitment and expertise34. Whilst financial rewards were not offered, steps were taken to minimize potential burdens for iDLD/iDLDPC to participate. For example, the sessions were carried out in the SLT’s places of work, and where iDLDPC were already meeting or taking their children, and therefore no participants incurred expenses. SLTs carried out the program of activities for iDLD during school hours so there were no additional time pressures for iDLD, or for the iDLDPC to transport the child to and from the session. Furthermore, the SLTs met with iDLDPC just before or after their child’s regular ‘pick-up time’ to minimize disruption to participants’ schedules. For future replications of the protocol we would recommend iDLD/iDLDPC are involved in conversations about how they would like to be rewarded, in line with current guidance33.

The advantage of this protocol is that it provides an evidence-based framework for eliciting views from iDLD/iDLDPC on a complex topic, which could be replicated for multiple purposes. For example, for carrying out a subsequent DLD research priority setting exercise or for research priority setting exercises with people with other kinds of speech, language and communication needs. Importantly, it may also be used as a basis for involving iDLD/iDLDPC or similar populations in research in the broader sense.

Acknowledgements

The RCSLT would like to acknowledge the Research Priorities working group and DLD work stream for their involvement and support in developing and carrying out the program of activities with iDLD and assisting with data collection. The RCSLT would also like to extend acknowledgement and gratitude to all individuals who participated in the sessions and gave their views on research priorities for DLD. We would also like to sincerely thank Blossom House School staff and students for their participation in and facilitation of the filming of the video accompanying this article.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Supporting resources | Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists |

References

- . Briefing paper: Language Disorder with a specific focus on Developmental Language Disorder Available from: https://www.rcslt.org/-/media/Project/RCSLT/language-disorder-briefing-paper.pdf (2020)

- Bishop, D. V. M., Snowling, M. J., Thompson, P. A., Greenhalgh, T. CATALISE-2 consortium. Phase 2 of CATALISE: a multinational and multidisciplinary Delphi consensus study of problems with language development: Terminology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 58, 1068-1080 (2017).

- Lyons, R., Roulstone, S. Well-being and resilience in children with speech and language disorders. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research. 61, 324-344 (2018).

- Durkin, K., Conti-Ramsden, G. Language, social behaviour, and the quality of friendships in adolescents with and without a history of specific language impairment. Child Development. 78 (5), 1441-1457 (2007).

- Conti-Ramsden, G., Durkin, K., Toseeb, U., Botting, N., Pickles, A. Education and employment outcomes of young adults with a history of developmental language disorders. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders. 53 (2), 237-255 (2018).

- . Standards of proficiency - Speech and language therapists Available from: https://www.hcpc-uk.org/resources/standards/standards-of-proficiency-speech-and-language-therapists/ (2020)

- Law, J., Dennis, J. A., Charlton, J. J. V. Speech and language therapy interventions for children with primary speech and/or language disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1, (2017).

- Ranson, M. K., Bennett, S. C. Priority setting and health policy and systems research. Health Res Policy Sys. 7 (1), 27 (2009).

- Rugdan, I. Setting health research priorities using the CHNRI method: IV. Key conceptual advances. J Glob Health. 6 (1), (2016).

- Rowbotham, N. J., et al. Adapting the James Lind Alliance priority setting process to better support patient participation: an example from cystic fibrosis. Res Involv Engagem. 5 (24), (2019).

- Chalmers, I., Atkinson, P., Fenton, M., Firkins, L., Crowe, S., Cowan, K. Tackling treatment uncertainties together: the evolution of the James Lind Initiative (JLI), 2003-2013. J R Soc Med. 106 (12), 482-491 (2013).

- Crowe, S., Fenton, M., Hall, M., Cowan, K., Chalmers, I. Patients', clinicians' and the research communities' priorities for treatment research: there is an important mismatch. Res Involvem Engagem. 1 (2), (2015).

- Tallon, D., Chard, J., Dieppe, P. Relation between agendas of the research community and the research consumer. Lancet. 335, 2037-2040 (2000).

- Madden, M., Morley, R. Exploring the challenge of health research priority setting in partnership: reflections on the methodology used by the James Lind Alliance Pressure Ulcer Priority Setting Partnership. Res Involv Engagem. 2 (12), (2016).

- . NHS England's Research Needs Assessment 2018 by Strategy and Innovation Directorate Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/nhs-englands-research-needs-assessment-2018.pdf (2020)

- Elberse, J. E., Pittens, C. A., de Cock Buning, T., Broerse, J. E. Patient involvement in a scientific advisory process: setting the research agenda for medical products. Health Policy. 107, 231-242 (2012).

- Harvey, N., Holmes, C. A. Nominal group technique: An effective method for obtaining group consensus. Int J Nurs Pract. 18 (2), 188-194 (2012).

- Fourie, R., Crowley, N., Oliviera, A. A Qualitative Exploration of Therapeutic Relationships from the Perspective of Six Children Receiving Speech-Language Therapy. Top Lang Disord. 31 (4), 310-324 (2011).

- Snape, D., et al. Exploring perceived barriers, drivers, impacts and the need for evaluation of public involvement in health and social care research: a modified Delphi study. BMJ Open. 4 (6), 004943 (2014).

- Morris, C., et al. Setting research priorities to improve the health of children and young people with neurodisability: a British Academy of Childhood Disability-James Lind Alliance Research Priority Setting Partnership. BMJ open. 5 (1), (2015).

- Pollock, A., St. George, B., Fenton, M., Crowe, S., Firkins, L. Development of a new model to engage patients and clinicians in setting research priorities. J Health Serv Res Policy. 19 (1), 12-18 (2014).

- . RCSLT Position Paper: Inclusive communication and the role of speech and language therapy Available from: https://www.rcslt.org/members/delivering-quality-services/inclusive-communication/inclusive-communication-guidance#section-8 (2020)

- Mander, C. . The triangle of accessibility. Communication and Intellectual Disability Course Notes. , (2009).

- . Royal College of Speech and Language Therapists. Research Priorities Available from: https://www.rcslt.org/members/research/research-priorities (2020)

- Archibald, L. M. D. Working memory and language learning: A review. Child Lang Teach Ther. 33 (1), 5-17 (2017).

- Henry, L. A., Botting, N. Working memory and developmental language impairments. Child Lang Teach Ther. 33 (1), 19-32 (2017).

- Sowerbutts, A., Finer, A. . DLD and Me: Supporting Children and Young People with Developmental Language Disorder. , (2019).

- Socol, Y., Shaki, Y. Y., Yanovskiy, M. Interests, Bias, and Consensus in Science and Regulation. Dose-Responnse. , (2019).

- . Briefing notes for researchers: involving the public in NHS, public health and social care research Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/9938_INVOLVE_Briefing_Notes_WEB.pdf (2020)

- . UK standards for Public Involvement Available from: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1U-IJNJCfFepaAOruEhzz1TdLvAcHTt2Q/view (2020)

- Bunning, K., Steel, G. Self-concept in young adult with a learning disability from the Jewish community. Br. J. Learn. Disabil. 35 (1), 43-49 (2007).

- . Good Practice for Payment and Recognition Available from: https://www.invo.org.uk/good-practice-for-payment-and-recognition-things-to-consider/ (2020)

- Gray-Burrows, K. A., Willis, T. A., Foy, R., Rathfelder, M., Bland, P., Chin, A., Hodgson, S., Ibegbuna, G., Prestwich, G., Samuel, K., Wood, L., Yaqoob, F., McEachan, R. Role of patient and public involvement in implementation research: a consensus study. BMJ quality & safety. 27 (10), 858-864 (2018).

- Blackburn, S., McLachlan, S., Jowett, S., Kinghorn, P., Gill, P., Higginbottom, A., Rhodes, C., Stevenson, F., Jinks, C. The extent, quality and impact of patient and public involvement in primary care research: a mixed methods study. Research Involvement and Engagement. 4 (16), (2018).

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

ABOUT JoVE

Copyright © 2024 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved