A subscription to JoVE is required to view this content. Sign in or start your free trial.

Assessing Rat Diaphragm Motor Unit Connectivity Outcome Measures as Quantitative Biomarkers of Phrenic Motor Neuron Degeneration and Compensation

* These authors contributed equally

In This Article

Summary

In this study, we present an in vivo method for estimating motor unit number and size to quantify rat diaphragm motor unit connectivity. A step-by-step approach to these techniques is described.

Abstract

Loss of ventilatory muscle function is a consequence of motor neuron injury and neurodegeneration (e.g., cervical spinal cord injury and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, respectively). Phrenic motor neurons are the final link between the central nervous system and muscle, and their respective motor units (groups of muscle fibers innervated by a single motor neuron) represent the smallest functional unit of the neuromuscular ventilatory system. Compound muscle action potential (CMAP), single motor unit potential (SMUP), and motor unit number estimation (MUNE) are established electrophysiological approaches that enable the longitudinal assessment of motor unit integrity in animal models over time but have mostly been applied to limb muscles. Therefore, the objectives of this study are to describe an approach in preclinical rodent studies that can be used longitudinally to quantify the phrenic MUNE, motor unit size (represented as SMUP), and CMAP, and then to demonstrate the utility of these approaches in a motor neuron loss model. Sensitive, objective, and translationally relevant biomarkers for neuronal injury, degeneration, and regeneration in motor neuron injury and diseases can significantly aid and accelerate experimental research discoveries to clinical testing.

Introduction

Phrenic motor neurons (MNs), extending from C3 to C6 myotome levels, form the final link from the central nervous system (CNS) to the diaphragm muscle1. Phrenic motor units (MUs) are comprised of a single spinal MN and its innervated diaphragm muscle fibers forming the smallest functional unit of the respiratory neuromuscular system. The ventilatory function requires adequate contraction of the diaphragm muscle achieved through coordinated activation of the phrenic MU pool2,3. Many neurological diseases, including amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), result in severe ventilatory impairment, ultimately contributing to the cause of death4.

Several electrophysiological approaches can be employed to evaluate and monitor the integrity of the motor unit (MU) pool in vivo. Compound muscle action potential (CMAP) reflects the summated depolarization of all muscle fibers in a specific muscle or muscle group after peripheral nerve stimulation and is sensitive to a range of neuromuscular conditions, including ALS5,6 and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA)7,8,9. A limitation of CMAP assessment is that collateral sprouting can lead to maintained CMAP amplitude and area even in the presence of MU loss10. To overcome this limitation, modifications have been made to the CMAP technique to evaluate both motor unit number and size11. Additionally, an in vivo study investigating the functional assessment of diaphragm CMAP by an electrophysiological system suggested that it may also be feasible to utilize the described diaphragm CMAP recording technique for motor unit number estimation12.

The incremental motor unit number estimation (MUNE) technique was initially introduced in the early 1970s by McComas et al. for the extensor digitorum brevis muscle in humans13. The incremental MUNE approach was a modification of the traditional CMAP recording technique during which a gradually increasing stimulation was delivered to record quantal, all-or-none submaximal increments as indices of single motor unit responses. The summed and averaged increments were used to calculate an estimate for the size of a single motor unit potential (SMUP). This calculated size was then divided into the CMAP amplitude to estimate the number of MUs innervating the muscle under examination11. MUNE demonstrates high sensitivity in detecting and monitoring motor unit loss, allowing for the identification of motor unit dysfunction before observable changes in measures such as CMAP amplitude or area14,15. In ALS patients, MUNE has proven to be exceptionally sensitive, serving as a prominent biomarker for disease onset, progression, and prognosis16,17.

Numerous adaptations of MUNE have been developed and widely used to assess MU function in conditions such as neurodegeneration, neural injury, and the natural aging process18,19,20,21. Since the initial description, various adaptations utilizing both electrophysiological responses and incremental force (mechanical) measurements have been employed in both human studies and animal models22. MUNE provides a non-invasive functional assessment of motor neuron connectivity with the muscle. Longitudinally applying MUNE enables the understanding of disease or induced phenotype progression and the evaluation of protective or regenerative effects of therapeutic interventions, both in clinical and preclinical settings. Regardless of the effectiveness of MUNE measures reproducibility and the clinical relevance of the technique for MU pools throughout most of the human body, efforts have largely focused on limb muscles in rodent muscles10,23,24,25.

Therefore, the objectives of this study were to describe an approach to obtaining compound muscle action potential (CMAP), SMUP, and phrenic motor unit number (MUNE) as in vivo assessments that can be used longitudinally in preclinical rodent studies to quantify the MUNE, motor unit size (represented as SMUP), and CMAP. Furthermore, we present representative data that highlights the loss of diaphragm MU number following intrapleural administration of a phrenic MN degenerative agent, cholera toxin B fragment conjugated to saporin (CTB-SAP).

Protocol

All procedures were approved and conducted in compliance with the guidelines established by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Missouri. Experiments were performed on adult male Sprague-Dawley rats, aged 11 to 15 weeks. These rats were housed in pairs and kept under a 12:12 light-dark cycle, with access to standard commercial pelleted food and HCl-treated water available at all times.

1. Animal preparation and anesthesia delivery

- Wear suitable personal protection equipment while handling rats.

- Administer inhalation anesthetic with 3-5% isoflurane, ensuring proper induction. Once the rat is adequately anesthetized, place it in a supine position and maintain the anesthesia with 1-3% inhaled isoflurane. Check the sufficiency of the anesthesia depth by gently applying pressure to the hindlimb footpad using forceps to ensure there is no withdrawal response.

NOTE: Based on the rat's size and weight, monitor the depth of anesthesia, and adjust the isoflurane concentration accordingly. - Maintain the temperature of 37 °C using a thermostatic warming plate to prevent variations in temperature that can impact CMAP amplitude and latency.

- Apply a veterinary petroleum-based ointment to the eyes to prevent dryness. Monitor the depth of anesthesia by observing the respiration rate and checking for withdrawal responses upon applying pressure to the footpad with forceps.

- Remove hair from the lower third of the chest and neck to be studied using clippers. Monitor the respiration of the rat during the entire experiment.

NOTE: Following the CMAP and MUNE recordings and discontinuation of anesthesia, do not leave the rat unattended until it has regained sufficient consciousness. Do not return the animal to the home cage until fully recovered.

2. Electrode placement and setup

- Place a pair of 28 G monopolar needle electrodes to record the CMAP, SMUP, and MUNE as depicted in Figure 1.

- Place the active (E1) needle electrode subcutaneously over the mid clavicular line inferior to the last rib border, and the reference (E2) needle electrode subcutaneously in the angle between the xyphoid process and last sternocostal cartilage.

NOTE: The needle electrodes should not be inserted into the diaphragm muscle; instead, they should be positioned in the subcutaneous area.

- Place the active (E1) needle electrode subcutaneously over the mid clavicular line inferior to the last rib border, and the reference (E2) needle electrode subcutaneously in the angle between the xyphoid process and last sternocostal cartilage.

- For stimulation of the phrenic nerve at the carotid sheet, use a pair of 28 G monopolar needle electrodes as the cathode and anode for nerve stimulation and placed subcutaneously over the lateral neck between the anterior and middle scalene muscles, separated by approximately 1 cm. Ensure that the placement of the stimulating needles is at the level below the fourth cervical vertebrae (C4).

NOTE: Avoid inserting the stimulating electrodes too deep to avoid injury of the phrenic nerve or other structure. Figure 1 illustrates electrode placement. - For the ground electrode, place a disposable surface electrode on the tail.

3. Data acquisition

- Phrenic CMAP

- Record phrenic CMAP responses by applying monophasic cathodic square-wave pulses with a duration of 0.1 ms and intensity ranging from 60 to 100 mA to stimulate the phrenic nerve.

- Obtain CMAP responses while progressively increasing the stimulus intensity until the amplitude of the response ceases to show any further increase. To ensure supramaximal stimulation, raise the stimulus intensity to approximately 120% of the level used to elicit a maximal response, and record an additional response. If the CMAP size no longer increases, consider this response as the maximum CMAP.

NOTE: Delivering stimulation during exhalation is preferable to minimize concurrent muscle activity noise during CMAP recording. - Measure and document the peak-to-peak amplitudes of the CMAP in millivolts (mV) (Figure 2).

NOTE: CMAP amplitude can be assessed base-to-peak and peak-to-peak. Clinical electrodiagnostic systems are often defaulted to assess base-to-peak which is calculated from the isoelectric baseline to the initial negative peak.

- Average single motor unit potential (SMUP) size and MUNE calculation

- Calculate the average SMUP size using an incremental stimulation technique.

- To elicit incremental responses, administer submaximal stimulation with a duration of 0.1 ms at 1 Hz frequency, gradually increasing the intensity in 0.03 mA increments until a minimal all-or-none response is achieved. Acquire the initial response with a stimulus intensity ranging between 2 mA and 10 mA.

- If the initial response does not occur with a stimulus intensity between 2 mA and 10 mA, modify the position of the stimulating cathode, either bringing it closer or moving it farther from the phrenic nerve in the neck, to decrease or increase the necessary stimulus intensity, respectively.

- If the first incremental response is achieved with a stimulus intensity ranging from 2 mA to 10 mA, save the first response and acquire additional increments with progressively higher stimulus intensities, adjusting in increments of 0.03 mA, to achieve a total of 9 additional increments that fulfill the following criteria in step 3.2.2.

NOTE: Each SMUP is quantified by subtracting each increment from the preceding increment.

- While measuring the incremental responses, make sure that each increment meets the following criteria:

- Make sure that the initial negative peak of the incremental responses aligns temporally with the negative peak of the maximal CMAP response.

NOTE: The slight movements observed due to background noise from respiratory cycles are inherent to the nature of the experiment. However, the consistent presence of SMUPs during live observation confirms their identity for that specific CMAP. - As the diaphragm is a dynamic muscle involved in respiration, each breathing cycle may induce baseline movement. Thus, verify the stability and absence of fractionation in each incremental response by confirming consistency across three duplicate responses.

NOTE: To distinguish low-amplitude evoked potentials, especially the first SMUP, from background noise due to respiratory activity, it is important to remain vigilant and observe for 3-4 respiratory cycles. Also ensure the alignment of peaks with those of the CMAP for accuracy. - Ensure that each increment is distinct and larger than the previous one. Therefore, visually distinguish incremental responses in real time, observing them as they overlay on the previously recorded increments.

NOTE: Multiple replicates of the stimulus at each amplitude might be conducted to ensure consistency in the increments and compliance with the predefined criteria. - After visually verifying each increment with the aforementioned criteria, confirm that the increment amplitude is at least 25 µV. If the increment is below 25 µV, discard the measurement and re-assess the response.

- Following the recording of 10 incremental responses, verify that the amplitude of each increment response is not greater than one-third of the combined amplitude of all 10 increments, representing the total amplitude of the final response. If this criterion is not satisfied, repeat the measurement of the 10 incremental responses.

NOTE: The threshold of one-third is based on the assumption that each incremental response represents the activation of a single motor unit. If the amplitude of any incremental response exceeds one-third of the combined amplitude of all ten increments, it suggests that the response may not be solely attributable to the activation of a single motor unit. Instead, it could be influenced by the recruitment of additional motor units or the presence of non-specific activity, such as electrical noise or artifacts22,26. - To estimate the average amplitude of the SMUPs, average the values of the 10 increments. Another method to measure average SMUP amplitude is to divide the entire amplitude of the final incremental response by the total number of increments11.

- Make sure that the initial negative peak of the incremental responses aligns temporally with the negative peak of the maximal CMAP response.

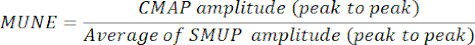

- Determine MUNE by dividing the maximum CMAP amplitude (peak-to-peak) by the average SMUP amplitude (peak-to-peak). In certain electrophysiological systems, SMUPs are recorded in microvolts (µV), while CMAP is usually expressed in millivolts (mV). If required, convert CMAP and SMUP measurements to the same units before calculating MUNE.

NOTE: Peak-to-peak CMAP, average SMUP, and MUNE are typically automatically calculated by clinic electromyography systems):

CMAP = Compound Muscle Action Potential

SMUP = Single Motor Unit Potential

MUNE = Motor Unit Number Estimation

- Calculate the average SMUP size using an incremental stimulation technique.

Results

The CMAP, SMUP, and MUNE techniques outlined in this report enable the recording of neuromuscular function in the diaphragm muscle employing minimally invasive electrode placement (Figure 1). The parameters of amplitude and area can be employed to characterize the supramaximal CMAP size, providing an overall measure of muscle group output (Figure 2). However, in our current methods, we rely on amplitude to quantify both CMAP and SMUP sizes. CMAP, SMUP, and MUNE ...

Discussion

In MN degenerative diseases, such as ALS, it is crucial to assess the MUs involved in ventilation28. Despite the occurrence of respiratory MN degeneration in ALS patients, the specific onset and progression of MN death remain incompletely understood29,30,31. Recognizing the significance of this aspect, various models, both genetic-based (e.g., SOD12,32<...

Disclosures

WDA has received research funding from NMD Pharma, Avidity Biosciences, and consulting fees from NMD Pharma, Avidity Biosciences, Dyne Therapeutics, Novartis, Design Therapeutics, Catalyst Pharmaceuticals, and Novartis.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded by a Spinal Cord Injury/Disease Research Program Grant from the Missouri Spinal Cord Injury/Disease Research Program (NLN and WDA).

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 2 mL Glass Syringe | Kent Scientific Corporation | SOMNO-2ML | |

| 50 mL, Model 705 RN syringe | Hamilton Company | 7637-01 | Utilized to conduct intrapleural injection |

| 5008 - Formulab Diet | LabDiet | 0001325 | |

| Autoclavable 26 G needles (26S RN 9.52 mm 40°) | Hamilton Company | 7804-04 | Utilized to conduct intrapleural injection |

| Cholera toxin B-subunit (CTB) | MilliporeSigma | C9903 | Utilized for intrapleural injection to label surviving motor neurons |

| Cholera toxin B-subunit conjugated to saporin (CTB-SAP) | Advanced Targeting Systems | IT-14 | Utilized for intrapleural injection to cause motor neuron death |

| Detachable Cable | Technomed | 202845-0000 | to connect the recorder electrode to the electrodiagnostic machine |

| Disposable 2" x 2" disc electrode with leads | Cadwell | 302290-000 | ground electrode |

| disposable monopolar needles 28 G | Technomed | 202270-000 | cathode and anode stimulating electrodes- recording electrodes |

| EMG needle cable (Amp/stim switch box) | Cadwell | 190266-200 | to connect monopolar electrodes to electrodiagnostic stimulator |

| Helping Hands alligator clip with iron base | Radio Shack | 64-079 | Maintaining recording electrode placement |

| Isoflurane (250 mL bottle) | Piramal Healthcare | ||

| monoject curved tip irrigating syringe | Covidien | 81412012 | utilized for application of electrode gel |

| PhysioSuite Physiological Monitoring System with RightTemp Homeothermic Warming | Kent Scientific Corporation | PS-RT | Includes infrared warming pad, rectal probe, and pad temperature probe |

| Pro trimmer Pet Grooming Kit | Oster | 078577-010-003 | clippers for hair removal |

| Saporin (SAP) | Advanced Targeting Systems | PR-01 | Utilized for intrapleural injection (control agent when injected by itself) |

| Sierra Summit EMG system | Cadwell Industries, Inc., Kennewick, WA | portable electrodiagnostic system | |

| SomnoSuite Low-Flow Digital Anesthesia System | Kent Scientific Corporation | SOMNO | Includes anti-spill, anti-vapor bottle top adapter; Y adapter tubing; charcoal scavenging filter |

| Sprague-Dawley rat | Envigo colony 208a, Indianapolis, IN | ||

| Veterinarian petroleum-based ophthalmic ointment | Puralube | 26870 | applied during anesthesia to avoid corneal injury |

References

- Mantilla, C. B., Zhan, W. -. Z., Sieck, G. C. Retrograde labeling of phrenic motoneurons by intrapleural injection. J Neurosci Methods. 182 (2), 244-249 (2009).

- Nichols, N. L., Satriotomo, I., Harrigan, D. J., Mitchell, G. S. Acute intermittent hypoxia induced phrenic long-term facilitation despite increased sod1 expression in a rat model of als. Exp Neurol. 273, 138-150 (2015).

- Nichols, N. L., Craig, T. A., Tanner, M. A. Phrenic long-term facilitation following intrapleural ctb-sap-induced respiratory motor neuron death. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 256, 43-49 (2018).

- Kiernan, M. C., et al. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Lancet. 377 (9769), 942-955 (2011).

- Boërio, D., Kalmar, B., Greensmith, L., Bostock, H. Excitability properties of mouse motor axons in the mutant sod1g93a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 41 (6), 774-784 (2010).

- Shibuya, K., et al. Motor cortical function determines prognosis in sporadic als. Neurology. 87 (5), 513-520 (2016).

- Lewelt, A., et al. Compound muscle action potential and motor function in children with spinal muscular atrophy. Muscle Nerve. 42 (5), 703-708 (2010).

- Mcgovern, V. L., et al. Smn expression is required in motor neurons to rescue electrophysiological deficits in the smnδ7 mouse model of sma. Hum Mol Genet. 24 (19), 5524-5541 (2015).

- Arnold, W. D., et al. Electrophysiological biomarkers in spinal muscular atrophy: Preclinical proof of concept. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 1 (1), 34-44 (2014).

- Harrigan, M. E., et al. Assessing rat forelimb and hindlimb motor unit connectivity as objective and robust biomarkers of spinal motor neuron function. Sci Rep. 9 (1), 16699 (2019).

- Arnold, W. D., et al. Electrophysiological motor unit number estimation (mune) measuring compound muscle action potential (cmap) in mouse hindlimb muscles. J. Vis. Exp: JoVE. (103), e52899 (2015).

- Martin, M., Li, K., Wright, M. C., Lepore, A. C. Functional and morphological assessment of diaphragm innervation by phrenic motor neurons. J. Vis. Exp: JoVE. (99), e52605 (2015).

- Mccomas, A., Fawcett, P. R. W., Campbell, M., Sica, R. Electrophysiological estimation of the number of motor units within a human muscle. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 34 (2), 121-131 (1971).

- Felice, K. J. A longitudinal study comparing thenar motor unit number estimates to other quantitative tests in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Muscle Nerve. 20 (2), 179-185 (1997).

- Vucic, S., Rutkove, S. B. Neurophysiological biomarkers in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Curr Opin Neurol. 31 (5), 640-647 (2018).

- Carleton, S., Brown, W. Changes in motor unit populations in motor neurone disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 42 (1), 42-51 (1979).

- Yuen, E. C., Olney, R. K. Longitudinal study of fiber density and motor unit number estimate in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Neurology. 49 (2), 573-578 (1997).

- Gooch, C. L., et al. Motor unit number estimation: A technology and literature review. Muscle Nerve. 50 (6), 884-893 (2014).

- Henderson, R. D., Ridall, P. G., Hutchinson, N. M., Pettitt, A. N., Mccombe, P. A. Bayesian statistical mune method. Muscle Nerve. 36 (2), 206-213 (2007).

- Shefner, J., et al. Multipoint incremental motor unit number estimation as an outcome measure in als. Neurology. 77 (3), 235-241 (2011).

- Stein, R. B., Yang, J. F. Methods for estimating the number of motor units in human muscles. Ann Neurol. 28 (4), 487-495 (1990).

- Shefner, J. M. Motor unit number estimation in human neurological diseases and animal models. Clin Neurophysiol. 112 (6), 955-964 (2001).

- Ahad, M., Rutkove, S. Correlation between muscle electrical impedance data and standard neurophysiologic parameters after experimental neurogenic injury. Physiol Meas. 31 (11), 1437 (2010).

- Kasselman, L. J., Shefner, J. M., Rutkove, S. B. Motor unit number estimation in the rat tail using a modified multipoint stimulation technique. Muscle Nerve. 40 (1), 115-121 (2009).

- Ngo, S., et al. The relationship between bayesian motor unit number estimation and histological measurements of motor neurons in wild-type and sod1g93a mice. Clin Neurophysiol. 123 (10), 2080-2091 (2012).

- Feasby, T., Brown, W. Variation of motor unit size in the human extensor digitorum brevis and thenar muscles. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 37 (8), 916-926 (1974).

- Nichols, N. L., Vinit, S., Bauernschmidt, L., Mitchell, G. S. Respiratory function after selective respiratory motor neuron death from intrapleural ctb-saporin injections. Exp Neurol. 267, 18-29 (2015).

- Nichols, N. L., et al. Ventilatory control in als. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 189 (2), 429-437 (2013).

- Cifra, A., Nani, F., Nistri, A. Respiratory motoneurons and pathological conditions: Lessons from hypoglossal motoneurons challenged by excitotoxic or oxidative stress. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 179 (1), 89-96 (2011).

- Kobayashi, Z., et al. Fals with gly72ser mutation in sod1 gene: Report of a family including the first autopsy case. J Neurol Sci. 300 (1), 9-13 (2011).

- Su, M., Wakabayashi, K., Tanno, Y., Inuzuka, T., Takahashi, H. An autopsy case of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with concomitant alzheimer's and incidental lewy body diseases. No to shinkei= Brain and nerve. 48 (10), 931-936 (1996).

- Lladó, J., et al. Degeneration of respiratory motor neurons in the sod1 g93a transgenic rat model of als. Neurobiol Dis. 21 (1), 110-118 (2006).

- Borkowski, L. F., Smith, C. L., Keilholz, A. N., Nichols, N. L. Divergent receptor utilization is necessary for phrenic long-term facilitation over the course of motor neuron loss following ctb-sap intrapleural injections. J Neurophysiol. 126 (3), 709-722 (2021).

- Nicolopoulos-Stournaras, S., Iles, J. F. Motor neuron columns in the lumbar spinal cord of the rat. J Comp Neurol. 217 (1), 75-85 (1983).

- Tosolini, A. P., Morris, R. Targeting motor end plates for delivery of adenoviruses: An approach to maximize uptake and transduction of spinal cord motor neurons. Sci Rep. 6 (1), 33058 (2016).

- Mchanwell, S., Biscoe, T. The localization of motoneurons supplying the hindlimb muscles of the mouse. Phil. Trans. R. , 477-508 (1981).

- Nair, J., et al. Histological identification of phrenic afferent projections to the spinal cord. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 236, 57-68 (2017).

- Courtine, G., et al. Can experiments in nonhuman primates expedite the translation of treatments for spinal cord injury in humans. Nat Med. 13 (5), 561-566 (2007).

- Friedli, L., et al. Pronounced species divergence in corticospinal tract reorganization and functional recovery after lateralized spinal cord injury favors primates. Sci Transl Med. 7 (302), 134 (2015).

- Arnold, R., et al. Nerve excitability in the rat forelimb: A technique to improve translational utility. J Neurosci Methods. 275, 19-24 (2017).

- Boriek, A., Rodarte, J., Reid, M. Shape and tension distribution of the passive rat diaphragm. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 280, R33-R41 (2001).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionExplore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved