A Macrophage-Tumor Spheroid Co-Invasion Assay

In This Article

Summary

Here, we present a protocol to investigate the interaction of primary human monocyte-derived macrophages with a tumor spheroid in a three-dimensional (3D) collagen I matrix, with the possibility to compare the impact of soluble and physical properties of the microenvironment on cell invasion.

Abstract

The interaction of immune and cancer cells and their respective impact on metastasis represents an important aspect of cancer research. So far, only a few protocols are available that allow an in vitro approximation of the in vivo situation. Here, we present a novel approach to observing the impact of human macrophages on the invasiveness of cancer cells, using tumor spheroids of H1299 non-small cell lung carcinoma cells embedded in a three-dimensional (3D) collagen I matrix. With this co-cultivation setup, we tested the impact of small interfering RNA (siRNA)-based depletion of regulatory factors in macrophages on the 3D invasion of cancer cells from the tumor spheroid compared to controls. This method allows the determination of different parameters, such as spheroid area or the number of invading cancer cells, and thus, to detect differences in cancer cell invasion. In this article, we present the respective setup, discuss the subsequent analysis, as well as the advantages and potential pitfalls of this method.

Introduction

Macrophages are a major part of the innate immune system and represent the first line of defense in many pathological conditions, such as infections or the clearing of cell debris after injuries1. During the last decades, the impact of immune cells on the progression of cancer has been an aspect of many studies. Accordingly, it has been shown that macrophages can facilitate metastasis by associating with primary tumors and becoming tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs)2. Macrophages can change their expression profile when exposed to cancer cells, favoring the escape of metastasis from the immune system3. In addition, it has been shown that cancer cells can utilize defects in the extracellular matrix (ECM) generated by macrophages to escape from the primary tumor and that their behavior is also manipulated by the uptake of secreted factors, including extracellular vesicles (EVs)4,5. This interplay of physical and chemical aspects requires the development of new methods to characterize the impact of immune cells on tumor spreading and the surrounding microenvironment.

Different approaches have been developed to study immune cell behavior in the context of metastasis in vivo6. However, as for all experiments including animals, a license for animal testing and an animal facility is needed; these approaches already demand a lot of development and preparation. Furthermore, the analysis is often complicated, especially in regard to live cell imaging, as not all specimens are accessible for most microscopical setups. The development of new methods to test hypotheses first in qualified in vitro conditions is also necessary and timely, as science and society aim for animal-free research to reduce the number of sacrificed animals.

In a recent publication7, we investigated the impact of primary human macrophages on the invasiveness of invading cancer cells from a tumor spheroid. For this purpose, we established a collagen I-based macrophage-tumor spheroid co-invasion assay. In this context, we aimed to elucidate the role of fast recycling pathways of the membrane-type 1 matrix metalloproteinase (MT1-MMP) in macrophages. We tested macrophages that were depleted for the super processive kinesin KIF16B, which we identified as a major driver of MT1-MMP recycling, and their impact on invasive capabilities of H1299- Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) cells from a solid spheroid. KIF16B-depleted macrophages show reduced levels of the membrane-bound MT1-MMP on their surface, while the H1299 cells themselves were untreated.

To our knowledge, no similar method has been described that allows for full imaging and analysis of macrophage-tumor-spheroid co-invasion. Although we focused in our recent publication7 on the analysis of individually migrating cells distant to the spheroid, the assay allows for multiple further investigations such as the number of invading strands, proteins involved in cancer cell-macrophage interaction, amount of collagen I degradation or other spheroid properties like the length of its perimeter.

Protocol

This protocol involves the use of primary human macrophages derived from donor blood samples. According to the ethical guidelines of the University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf, blood samples were collected, and donors were compensated. Further processing of the samples was performed following given safety guidelines (e.g., treatment of untested samples). Work with primary human macrophages in this study has been judged unobjectionable by Ärztekammer Hamburg, Germany.

1. Generation of H1299 tumor spheroids in a scaffold-free approach (3 days in advance)

- Cultivate cancer cells in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2 in 25 cm2 cell culture flasks (see Table of Materials) with cancer cell medium (Dulbecco's modified eagles' medium [DMEM] + 1% penicillin-streptomycin [pen-strep] + 10% fetal bovine serum [FBS] + 0.1 mM nonessential amino-acids + 2 mM L-glutamine) until 80% confluence.

- Wash the cells once with Dulbecco's phosphate buffered saline (DPBS) and detach them by adding 1 mL of trypsin-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) (0.25%, phenol-red) for 2 min. Stop the enzymatic reaction by adding 2 mL of cancer cell media and check the detachment under a light microscope.

NOTE: It is important that the cancer cells are separated and that no cancer cell clusters are present. - Transfer the cell suspension into a 15 mL reaction tube and centrifuge it at 245 x g for 5 min. Afterward, remove the trypsin solution by pipetting or using a pump, wash the pellet subsequently by adding 5 mL of DPBS, and centrifuge them again under the same conditions.

- Resuspend the pellet in 5 mL of cancer cell medium and count the cells, e.g., with a Neubauer chamber. Transfer 8,000 H1299-GFP cells into a 96-well ultra-low adhesion plate (see Table of Materials) in a final volume of 25 µL of cancer cell medium.

- Incubate the chamber for 3 days in the incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Check the spheroids under the microscope for uniformity. Do not consider spheroids with a lower density or unattached individual cancer cells for further experiments.

2. Preparation of primary human macrophages from donor blood samples

- If donor blood samples are not used for cell isolation immediately, store them at 4 °C, with shaking.

- Transfer 20 mL of blood from a transfusion bag into a 50 mL reaction tube.

- Subsequently, prepare a new 50 mL tube and add 15 mL of lymphocyte separation medium (LSM).

- Carefully add the 20 mL of blood to each LSM-containing tube without mixing and centrifuge it at 450 x g for 30 min at 4 °C.

- In the meantime, prepare a new 50 mL tube and add 10 mL of cold Roswell Park Memorial Institute (RPMI)-1640 medium.

- After centrifugation, transfer the dense, white phase ("buffy coat") within the blood-containing tube into the prepared RPMI-containing tube and add up the volume to 50 mL with cold RPMI.

- Centrifuge the suspension at 450 x g for 10 min at 4 °C and discard the supernatant.

- Resuspend the cells in 10 mL of cold RPMI.

- Centrifuge the mix again at 450 x g for 10 min at 4 °C, discard the supernatant, and resuspend the pellet in 50 mL of RPMI.

- Centrifuge the sample again at 450 x g for 10 min at 4 °C, discard the supernatant, and resuspend the cell pellet in 1.5 mL of cold monocyte buffer (0.5% human serum albumin + 5 mM EDTA in 25 mL of DPBS).

- Put the cell suspension on ice, add 250 µL of anti-CD14 microbeads, and incubate for 15 min on ice.

- Prepare a separation column by addition of a filter at a magnetic separator rack and add 900 µL of monocyte buffer for equilibration.

- Pour the cell suspension onto the filter and let it flow through into a waste tube by gravity.

- Wash the column, which contains the cells bound to the magnetic beads, by adding 1 mL of monocyte buffer.

- Prepare a fresh 50 mL tube containing 20 mL RPMI and replace the waste tube underneath the column.

- Add 3 mL of monocyte buffer to the column, remove it from the magnetic rack, and attach the stamp.

- Press the cells into the prepared 50 mL tube and fill it up to 30 mL of volume with RPMI.

- Count the cells (e.g., using a Neubauer counting chamber) under a light microscope and adjust the cell number by adding RPMI to 2 x 106 cells/mL.

- Seed 1 mL of the cell suspension into each well of a 6-well chamber and incubate the plate for 2-4 h at 37 °C and 5% CO2.

- Check if the cells adhered properly and replace the RPMI with 1.5 mL monomedium (20% human serum + 1% pen-strep in RPMI).

- Change the medium after 24 h of incubation. Under these conditions, monocytes differentiate into macrophages within 6 days.

3. Macrophage preparation

- At the day of the experiment, detach the macrophages with an appropriate amount of accutase for the individual culture conditions. For example, use 500 µL of accutase if the cells are seeded in a 6-well dish. Incubate the cells for about 40 min within the solution, wash them once with 2 mL of DPBS, and count them with a Neubauer chamber.

- For one spheroid, dilute the desired number of macrophages in 40 µL of collagen I mix (2.5 mg/mL rat tail collagen I) and mix them by shortly vortexing the reaction tube. In the experiments conducted, 200,000 cells/mL have shown a detectable difference on the invasion of cancer cells. Keep the collagen-cell-mix on ice, as it will start to polymerize quickly at room temperature (RT).

4. Setup of the co-invasion assay

NOTE: Depending on the format of the imaging chamber, the purpose of the analysis, or the respective imaging setup, the tumor spheroid might need to be transferred from the ultra-low adhesion plate and the values for collagen and media adapted. The following steps describe the setup for one sample in a 15-well µ-slide.

- First, wash the spheroid by adding 300 µL of DPBS. Cut the tip of a 1 mL blue pipette tip and take up the spheroid with DPBS. After aspiration of the spheroid settled into the tip, briefly push the pipette to the bottom of the imaging chamber to transfer the tumor-spheroid by surface tension.

NOTE: It is important to note that the friction at unmodified tips might disturb the integrity of the spheroid. - Remove residual DPBS transferred with the spheroid as much as possible by pipetting.

- Swiftly add 40 µL of collagen I/macrophage mix (see step 3.4) to the imaging chamber that contains the H1299-GFP spheroid.

- Transfer the plate into a cell incubator and incubate the plate for 30 min at 37 °C and 5% CO2 under humid conditions to fully polymerize the collagen mix.

- After polymerization, carefully add 25 µL of cancer-cell media to each well and incubate the plate for 3 days in the incubator under the previously described conditions. If needed, image the live sample with a laser scanning microscope at desired time points.

5. Additional fixation and staining

- In order to perform immunofluorescence staining, fix the macrophages and H1299-GFP spheroids within the collagen I matrix. First, carefully remove the supernatant from each sample with a pump without touching the matrix.

NOTE: To avoid sample destruction, the supernatant can also be removed by manual pipetting without using a pump. - Add 50 µL of 3.7% formaldehyde in DPBS to each well and incubate the samples for 5 min on ice. Afterward, remove the fixative solution and add 50 µL of fresh fixing solution again to it. This step is important to achieve a more uniform formaldehyde level within the well. Incubate the samples overnight at 4 °C.

NOTE: Depending on the amount of collagen I mix, the incubation times might extend to several hours. - Remove the fixative on the next day and wash the samples by repeated removal of at least two times DPBS depending on the volume of the imaging chamber. Briefly incubate them for 5 min on ice on a shaker before removing the DPBS by pipetting. The samples are now ready for staining.

- Stain the samples by adding a 1:100 mix of 4',6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) (1 mg/mL, to stain nuclei), and phalloidin 568 (to stain F-actin) in DPBS for at least 30 min and wash them twice with DPBS before imaging.

6. Imaging and analysis of different parameters of tumor growth

NOTE: The following steps can be performed for either fixed live-cell imaging samples.

- For the observation of the tumor-spheroid, use an inverted laser scanning microscope equipped with a 10x objective that allows imaging of a z-stack of roughly the lower third of the spheroid.

NOTE: Due to the thickness of the sample, a 2-photon microscope might also be advantageous. For optimal identification of individual cells, higher laser power and exposure time might be needed. - After the acquisition, combine the stacks by z-projection using Fiji, which is ImageJ software (Fiji). Further, process the resulting channel of the H1299-GFP signal by applying an auto threshold (e.g., Huang auto-threshold) and remove residual noise by despeckling the image depending on the amount of background and signal intensity.

- Measure the spheroid parameters using Fiji.

- Area: Measure the spheroid size with the Wand tool.

- Perimeter: Include the Perimeter into the measurement settings.

- Diameter: Include the Feret's Diameter into the measurement settings.

- Circularity: Include the Shape Descriptors into the measurement settings.

- Measure the individual cancer cell parameters using Fiji.

- Measure the number of invading cells.

- Choose the central spheroid with the Wand tool and delete the signal. This will remove the spheroid as well as all connected signals of cells, which are still attached to the spheroid, from the analysis.

- Afterwards, use the Analyze Particle tool or quantify all residual individual signals.

NOTE: The result will be the number of invading cancer cells. In addition, the result could also show the representative area covered by the cancer cells and be interpreted as collective invasion or single-cell invasion, depending on the size of the area. To further validate the number of invading cancer cells, a mask of the analyzed particles could be laid above the DAPI channel, and nuclei counted.

- Measure the number of invading cells.

- Further, evaluate the results using a statistical program such as GraphPad Prism or Microsoft Excel.

NOTE: This protocol has been shown to be both robust and flexible. It has been used in our lab more than 50 times, always with primary human macrophages from at least 3 donors, to account for donor variability. In its current form, the protocol has been shown to lead to a success rate of 90-95%. However, as the setup is complex, varying results might also be an outcome, as the interaction of macrophages for every spheroid is individual. Thus, performing the experiment at least 3 times with 5 spheroids is suggested to get a statistically significant result.

Representative Results

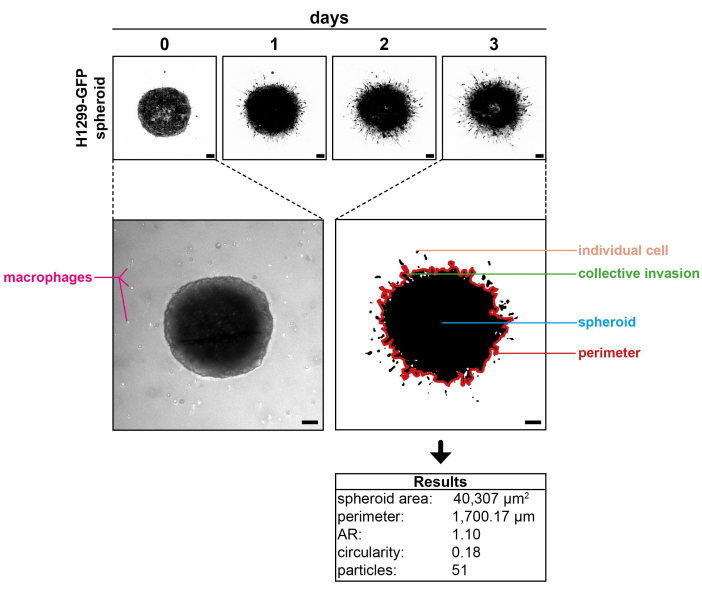

Figure 1 shows an H1299-GFP spheroid imaged at the respective days of incubation in a collagen I matrix. A respective brightfield image, taken at day 0, also shows the primary human macrophages cocultured with the spheroid. The representative image recorded on day 3 of the experiment is enlarged after processing. Different parameters that can be analyzed are indicated, including the number of invading cells, sites of collective invasion, and spheroid perimeter. The table included shows the results gained from this image. The number of detected signals matches the visual impression. No disruptions of the central spheroid are visible, indicating actual individual cancer cell invasion rather than cells derived from spheroid debris. The results of different spheroids and conditions can now be compared via statistical analysis.

Figure 1: Representative results. (Top panel) H1299-GFP spheroid imaged at day 0, day 1, day 2, and day 3 of incubation in a collagen I matrix. (Middle left panel) A brightfield image of the spheroid showing the cocultured primary human macrophages. (Middle right panel) A representative image acquired at day 3 enlarged after processing, showing the different parameters that can be analyzed (spheroid perimeter in red; traced manually for better visualization). (Bottom panel) The results obtained from the image on the middle right panel. Note: Macrophages are not visible, as only the GFP channel was recorded to elucidate the cancer cell behavior. Scale bars: 100 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Discussion

The invasion of cancer cells remains an important yet understudied topic in the context of co-invading immune cells like macrophages. Collective and individual cancer cell invasion are critical processes during metastasis and have been shown to lower the survival rate of cancer patients due to the multiplicity of infestations of different organs8,9. In vivo studies are complex and are restricted to laboratories with access to animal housing facilities. Moreover, it is also difficult to control in vivo conditions or to specifically manipulate individual aspects. Therefore, the need for a more accessible system remains essential to answer basic questions in the first line of research.

With the method presented here, we developed a way in which i) immune cell and ii) cancer cell behavior, iii) growth and development of a solid spheroid, and iv) the impact of cells in the surrounding tumor microenvironment (TME) on ECM components can be further analyzed. It can be used to compare the impact of modified (e.g., depleted for specific regulators by siRNA treatment) macrophages on the invasiveness of individual cancer cells from a solid spheroid. Whether the physical rearrangement of the TME or secreted factors represents the main cause of the observed cancer cell behavior is currently unclear and needs to be analyzed in more detail.

In addition, also the cancer cells themselves could be manipulated, for example by siRNA treatment or knockout of specific regulators. Moreover, the analysis can be improved by comparing the number of counted nuclei within the identified cell profile to allow for a more precise determination of invading cancer cells.

We have used this assay to determine the impact of macrophages in the TME on the invasion of tumor cells. However, it should also be noted that tumor cells are likely to influence the activity of macrophages, possibly through secreted factors within the media. It would thus also be a worthwhile endeavor to identify changes in the macrophages, such as altered polarization status (M1 vs. M2) by immunofluorescence staining using respective antibodies. In the past, the comparison between cells growing in monolayers and those cultured in a 3D environment has shown significant differences in their expression profiles10.

In addition, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) of macrophage subpopulations and their integration into the experimental procedure could be instructive. Last but not least, more detailed imaging of the contact areas where macrophages interact with cancer cells or the tumor spheroid surface could lead to the identification of further mechanisms relevant to 3D invasion and interaction.

Of note that can not be controlled fully is the precise positioning of the spheroid in the center of the well after the addition of the collagen-mix. The amount of collagen underneath the spheroid is especially hard to regulate. Here, other methods have been established to allow for precise positioning of the spheroid, e.g., on top of agarose molds with higher sample numbers11. However, as the release of cytokines is a common mechanism, all spheroids within this multi-spheroid assay are exposed to secreted factors, and the number of immune cells acting on a single spheroid is hard to control.

One basic limitation of this protocol is the ability of cancer cell lines to form uniform spheroids, thus being only applicable to a subset of cell lines. For example, MeWo melanoma cells form uneven, sheet like 3D structures but no uniform spheroids.

It should also be noted that the assay is highly adaptable, as many of its features can be modified, such as the ECM material, the cell number or by adding specific factors such as cytokines to the supernatant. It should, therefore, be highly suitable for initial in vitro studies of the cancer cell/immune cell interaction and can be tailored to the specific research question that is currently addressed.

Disclosures

The authors declare that no competing interests exist.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Andrea Mordhorst for excellent technical support and cell culture and Martin Aepfelbacher for continuous support. Work on macrophage invasion in the SL lab is supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (CRC877/B13; LI925/13-1).

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 15 µ-Slide Angiogenesis | ibidi | 81506 | |

| Accutase | Invitrogen | 00-4555-56 | |

| Alexa Fluor 568 Phalloidin | ThermoFisher Scientific | A12380 | |

| CD14 MicroBeads | Miltenyi Biotec | 130-050-201 | |

| CO2 Incubator | Binder | ||

| Collagen I Rat Tail | Corning | 354236 | |

| DAPI | AppliChem | ||

| DMEM (1x) + GlutaMAX | Gibco | 31966-021 | |

| DPBS | Anprotec | MS01Y71003 | |

| FBS | Bio&Cell | FBS. S 0613 | |

| Fiji | NIH | ImageJ 2 Version: 2.3.0/1.53s | |

| Formaldehyde 37% | 252549-500ml | Sigma-Aldrich | |

| H1299-GFP cell line | |||

| Human serum albumin | Sigma-Aldrich | A5843 | |

| Leica TCS SP8 X | Leica | ||

| l-glutamine | Gibco | 25030-024 | |

| Lymphocyte Seperation Medium (LSM) 1077 | PromoCell | C-44010 | |

| MS Columns | Miltenyi Biotec | 130-042-201 | |

| nonessential amino-acids | Sigma-Aldrich | 11140050 | |

| Pen Strep | Gibco | 15140-122 | |

| RPMI-1640 | Gibco | 81275-034 | |

| TC-Platte 96 Well, BIOFLOAT, R | SARSTEDT | 83,39,25,400 | |

| VORTEX-GENE 2 | Scientific Industries |

References

- Lendeckel, U., Venz, S., Wolke, C. Macrophages: shapes and functions. ChemTexts. 8 (2), 12 (2022).

- Dallavalasa, S., et al. The role of tumor associated macrophages (TAMs) in cancer progression, chemoresistance, angiogenesis and metastasis - Current status. Curr Med Chem. 28 (39), 8203-8236 (2021).

- Pan, Y., Yu, Y., Wang, X., Zhang, T. Tumor-associated macrophages in tumor immunity. Front Immunol. 11, 583084 (2020).

- Boutilier, A. J., Elsawa, S. F. Macrophage Polarization States in the Tumor Microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 22 (13), 6995 (2021).

- Wenzel, E. M., et al. Intercellular transfer of cancer cell invasiveness via endosome-mediated protease shedding. Nat Commun. 15 (1), 1277 (2024).

- Anfray, C., Ummarino, A., Calvo, A., Allavena, P., Torres Andon, F. In vivo analysis of tumor-associated macrophages in the tumor microenvironment. Methods Mol Biol. 2614, 93-108 (2023).

- Hey, S., Wiesner, C., Barcelona, B., Linder, S. KIF16B drives MT1-MMP recycling in macrophages and promotes co-invasion of cancer cells. Life Sci Alliance. 6 (11), e202302158 (2023).

- Wu, J. S., et al. Plasticity of cancer cell invasion: Patterns and mechanisms. Transl Oncol. 14 (1), 100899 (2021).

- Shi, X., et al. Mechanism insights and therapeutic intervention of tumor metastasis: latest developments and perspectives. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 9 (1), 192 (2024).

- Li, G. N., Livi, L. L., Gourd, C. M., Deweerd, E. S., Hoffman-Kim, D. Genomic and morphological changes of neuroblastoma cells in response to three-dimensional matrices. Tissue Eng. 13 (5), 1035-1047 (2007).

- Lin, Y. N., et al. Monitoring cancer cell invasion and T-cell cytotoxicity in 3D culture. J Vis Exp. 160, e61392 (2020).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionExplore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

ABOUT JoVE

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved