Effects of Thinking Abstractly or Concretely on Self-control

Source: Diego Reinero & Jay Van Bavel—New York University

Whether it's refraining from having a second serving of ice cream, studying instead of attending a fun party, or deciding to put money away in a savings account, sacrificing short-term outcomes in favor of long-term outcomes (i.e., delaying gratification) is a central tenant of self-control. When people apply self control, they engage numerous psychological processes to help them achieve their goal. These self-regulatory processes have been studied by psychologists for decades.

A decision to resist tempting short-term rewards can depend on an individual's mindset and focus. Psychologists have found evidence that how someone construes an event can influence how they make judgments and decisions, a theory called Construal Level Theory (CLT). In particular, CLT asserts that the same object or event can be represented at multiple levels of abstractness or psychological distance, most commonly either a high-(abstract/distant) or low-(concrete/near) level of construal.1 Thinking about a situation with high-level construal entails emphasizing the global, superordinate, central features of an object or event (i.e,, zooming out and looking at the big picture), whereas thinking about a situation with low-level construal entails focusing on its unique and specific features. For example, thinking about children playing catch with high-level construal, one might describe this activity as "children having fun", whereas with a low-level construal, one might focus instead on specific features such as the color of the ball or age of the children.

The following experiment tests whether approaching a decision or situation with high-level construal will lead to greater self-control than low-level construal. This experiment utilizes a common method of priming a participant's level of construal through asking a series of "why" (high-level manipulation) or "how" (low-level manipulation) questions.2

1. Data Collection

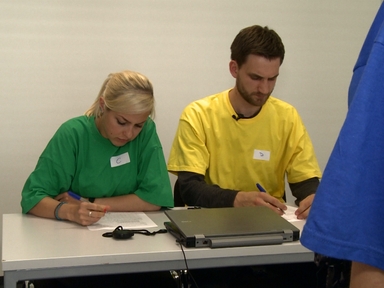

- Conduct a power analysis and recruit a sufficient number of participants and obtain informed consent from the participants.

- Randomly assign half of the participants to the high-level condition and the other half to the low-level condition.

- As a cover story, tell the participants that they will be completing materials for two independent studies during the 30-min session.

- Have participants first complete a survey, ostensibly described as a survey of their opinio

Analyzing the manipulation check revealed that participants exposed to why questions generated responses that reflected higher levels of construal compared with those exposed to how questions. The data (Figure 1) typically indicate that those primed in high-level construal, prefer immediate over delayed outcomes less than those primed in low-level construal. This suggests that high-level construal leads to greater self-control than low-level construa

How people construe a situation can shape their overall mindset and focus, influencing consequent judgments and decisions. Participants who answered questions of why they engaged in actions displayed a reduced tendency to prefer immediate over delayed outcomes compared with those who responded to questions of how they engaged in actions. That is, time delay had less of an impact on those individuals primed to a high-level versus a low-level construal. This reflects that those who construed the situation

- Trope, Y., & Liberman, N. (2003). Temporal construal. Psychological Review, 110, 403-421.

- Freitas, A. L., Gollwitzer, P. M., & Trope, Y. (2004). The influence of abstract and concrete mindsets on anticipating and guiding others' self-regulatory efforts. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 739-752.

- Bargh, J. A., & Chartrand, T. (2000). The mind in the middle: A practical guide to priming and automaticity research. In H. T. Reis & C. M. Judd (Eds.), Handbook of research methods in social and personality psychology (pp. 253-285). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Mischel, W., Shoda, Y., & Rodriguez, M. L. (1989). Delay of gratification in children. Science, 244, 933-938.

- Metcalfe, J., & Mischel, W. (1999). A hot/cool system analysis of delay of gratification: Dynamics of willpower. Psychological Review, 106, 3-19.

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

Skip to...

Videos from this collection:

Now Playing

Effects of Thinking Abstractly or Concretely on Self-control

Social Psychology

6.5K Views

The Rouge Test: Searching for a Sense of Self

Social Psychology

54.1K Views

Effects of Thinking Abstractly or Concretely on Self-control

Social Psychology

6.5K Views

The Social Dimension of Stress: Experimental Manipulations of Social Support and Social Identity in the Trier Social Stress Test

Social Psychology

13.6K Views

Experimental Paradigm for Measuring the Effects of Self-distancing in Young Children

Social Psychology

7.8K Views

Creating Virtual-hand and Virtual-face Illusions to Investigate Self-representation

Social Psychology

13.1K Views

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved