Stress-Strain Characteristics of Steels

Source: Roberto Leon, Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering, Virginia Tech, Blacksburg, VA

The importance of materials to human development is clearly captured by the early classifications of world history into periods such as the Stone Age, Iron Age, and the Bronze Age. The introduction of the Siemens and Bessemer processes to produce steels in the mid-1800s is arguably the single most important development in launching the Industrial Revolution that transformed much of Europe and the USA in the second half of the 19th century from agrarian societies into the urban and mechanized societies of today. Steel, in its almost infinite variations, is all around us, from our kitchen appliances to cars, to lifelines such as electrical transmission networks and water distribution systems. In this experiment we will look at the stress-strain behavior of two types of steel that bound the range usually seen in civil engineering applications - from a very mild, hot rolled steel to a hard, cold rolled one.

The term steel is commonly used to denote a material that is principally iron (Fe), often in the 95% to 98% range. Pure iron is allotropic, with a body-centered cubic (BCC) structure at room temperature that changes into a face-centered cubic (FCC) structure above 912°C. The empty spaces in the FCC structure and imperfections in the crystal structure allow for other atoms, such as carbon (C) atoms, to be added or removed through diffusion from the interstitial (or empty) spaces. These additions, and the subsequent development of different crystal structures, are the result of heating and cooling at different rates and temperature ranges, a process known as heat treatment. This technology has been known for over 2000 years, but kept secret for many years in applications such as Damascus steel, which utilized Wootz steel from India (≈300AD).

If we expand the open circles in the FCC structure until the spheres begin to touch, and then cut a basic cube for this atomic structure, the result is the unit cell. Spheres with 41.4% of the iron atom diameter can be added before these new spheres begin to touch the iron ones. Carbon atoms are 56% of the diameter of iron ones, so the new structure becomes distorted as carbon atoms are introduced. The properties of steel can be manipulated by changing the size, frequency, and distribution of these distortions.

Wrought iron, one of the most useful predecessors of steel, has a carbon content of more than 2%. It turns out that the optimum carbon content for steels from civil applications is the range of 0.2% to 0.5%. Many of the early metallurgical treatment process were aimed at bringing carbon contents to these levels in volumes that were economical to produce. The Bessemer process in the USA and the Siemens process in the UK are two of the more successful examples of those early techniques. The processes most commonly used today are the electric arc furnace and the basic oxygen furnace. In addition to carbon, most modern steels contain manganese (Mn), chromium (Cr), molybdenum (Mo), copper (Cu), nickel (Ni), and other metals in small amounts to improve strength, deformability, and toughness. A simple example of the effect of these alloys on engineering properties is the so-called carbon equivalent (CE):

The CE is a useful index in determining the weldability of a particular steel; typically, a CE < 0.4% is representative of a steel that is weldable. As many connections in metal structures are made by welding, this is a useful index to remember when specifying materials for construction.

As noted in the JoVE video regarding "Material Constants" , for modeling purposes we need to establish some relationship between stress and strains. The best simple description of the behavior of many materials is given by a stressstrain curve (Fig.1). As a result of problems with buckling when loading in compression and difficulties in loading a material uniformly in more than one direction, a uniaxial tensile test is usually run to determine a stress-strain curve. This test provides basic information on the main engineering characteristics primarily of homogeneous metallic materials.

The typical tension test is described by ASTM E8. ASTM E8 defines the type and size of test specimen to be used, typical equipment to be used, and data to be reported for a metal tension test.

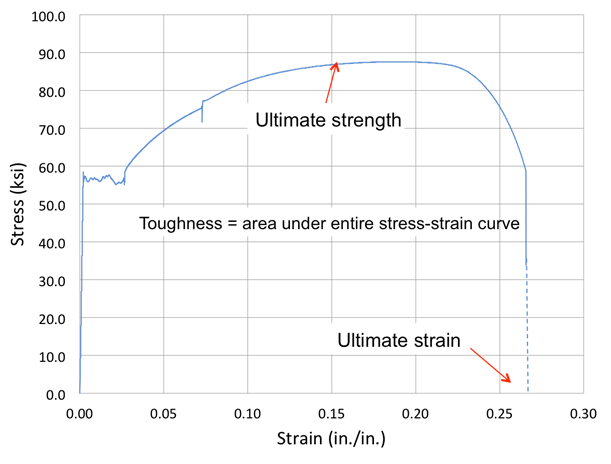

Figure 1: Stress-strain curve for low carbon steel.

Since we need to measure through very large plastic strains, the strain measurement cannot always be made with strain gages over the entire deformation range (up to 40%); the glue will almost always fail before the specimen fractures. An extensometer, which consists of a small C-frame with cantilevered arms instrumented with strain gages and appropriately calibrated, is typically used up to about 20%. Since the extensometer is an expensive and delicate instrument, it needs to be removed before the specimen fractures; the test will be stopped, and the extensometer removed shortly after the specimen reaches its maximum stress and the maximum deformation estimated from marks on the specimen.

The main properties of interest are (Fig. 2):

Proportional limit: The proportional limit is the maximum stress for which stress remains linearly proportional to strain, i.e. for which Hooke's law is strictly applicable (JoVE video - "Material Constants"). This value is generally determined by looking at changes in stress rate when the test is run under constant crosshead speed conditions. In the linear elastic range, the stress rate is proportional to the strain rate and is, ideally, constant. As the material begins to plastify, as evidenced by an increase in the strain rate, the stress rate begins to decrease. The proportional limit is taken as the stress when the initial stress rate begins to decrease.

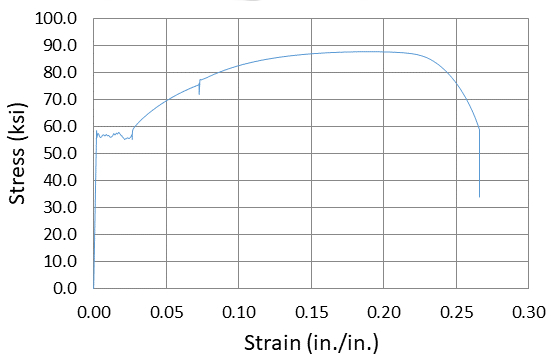

Yield point: Many metals exhibit a sharp yield point or stress at which the strains continue to increase rapidly without any increase in stress. This is evidenced by a horizontal line, or yield plateau, in the stress-strain curve. The yield point corresponds roughly to the load at which slip begins to occur in the atomic lattices. This slip is triggered by reaching some critical shear force and is much lower than can be calculated from first principles because of the numerous imperfections in the crystal structure. In some materials, such as the mild steel tested in this experiment, there is a small but noticeable decrease in stress before the material reaches the yield plateau, giving rise to upper and lower yield points. For materials that do not exhibit a clear yield point, an equivalent yield strength is used. We will look at this definition in detail in the JoVE video regarding "Stress Strain Characteristics of Aluminum", which deals with these properties in aluminum.

Figure 2: Definitions of variables at low strains.

Elastic modulus: The modulus of elasticity of a material is defined as the slope of the straight-line portion of the stress-strain diagram as shown in Fig.2. This property was discussed in the JoVE video regarding "Material Constants". E is a relatively large number: 30 x 106 psi (210Gpa) for steel; 10 x 106 psi (70 GPa) for aluminum; 1.5 X 106 psi (10.5 GPa) for oak; and 0.5 x 106 psi (3.5 GPa) for plexiglass.

Modulus of resilience: The modulus of resilience is the area under the elastic portion of the stress-strain diagram and has units of energy per unit of volume. The modulus of resilience measures the capacity of a material to absorb energy without undergoing permanent deformations.

Strain hardening modulus: As the slip, or dislocation movements, that triggered the yield plateau begin to reach the grain boundaries (or areas where the lattices are oriented at different angles), the dislocations begin to "pile up", and additional energy is required to propagate their movement into other grains. This leads to a stiffening in the stress-strain behavior, although the strain hardening modulus is usually at least one order of magnitude below Young's modulus.

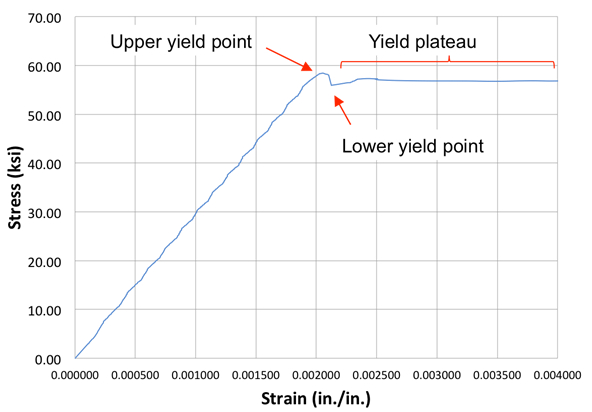

Ultimate strength: This is the maximum value of the engineering stress reached during the test and occurs shortly before the specimen begins to neck (or change area) appreciably (Fig. 3).

Maximum strain: This value is taken as the strain value when the specimen fractures. Since the extensometer generally has been removed by the time we get to this point in the test and the deformation has localized (necking) into a very short distance along the length of the specimen, this value is very difficult to measure experimentally. For this reason, both a uniform elongation and a percent elongation are often used when specifying materials instead of a maximum strain value.

Figure 3: Definitions at large strains.

Uniform Elongation: The percent elongation is defined as the percent elongation (change in length/original length) of the specimen just before necking occurs.

Percent Elongation: Generally two marks, nominally 2 in. apart, are made on the specimen before testing. After the test, the two pieces of the fractured specimen are put together as best as possible, and the final deformation between the marks is remeasured. This is a crude, but useful way of specifying minimum elongation for materials in an engineering context.

Percent area: Similarly to percent elongation, it is possible to try to make a measurement of the final area of the fractured specimen. By dividing the force just before fracture by this area, it is possible to obtain an idea of the true strength of the material.

Toughness: Toughness is defined to be the total area under the stress-strain diagram. It is a measure of the capability of a material to undergo large, permanent deformations prior to fracture. Its units are the same as those for the modulus of resilience.

The properties described above can be used to assess how well a given material will conform to the performance criteria discussed in the JoVE video regarding "Material Constants". Insofar as safety is concerned, the strength and deformation capacity characteristics are key; these characteristics are usually grouped under the term of ductile behavior. Ductile behavior implies that a material will yield and be able to maintain its strength over a large plastic deformation regime. A large toughness is desirable, which in practice means that a structure will give signs of impending failure, e.g. very large visible deformation before a catastrophic collapse occurs, allowing its occupants time to evacuate the structure.

In contrast, materials that exhibit brittle behavior, will generally fail in a sudden, catastrophic way. This is the case of cementatious and ceramic materials, which exhibit poor tensile capacity. A concrete beam will fail in this fashion because it is very weak in tension. To remedy this pitfall, one places reinforcing steel bars in the tensile region of concrete beams, turning them into reinforced concrete beams.

It is important to realize that brittle and ductile behavior is not an inherent material behavior. As we will see in the JoVE video regarding "Rockwell Hardness Test", subjecting a carbon steel that is ductile at room temperature and under a low strain loading rate conditions to very fast strain loading condition (impact) at low temperatures can result in brittle behavior. In addition, it is important to recognize that some materials, e.g., cast iron, can be very brittle in tension, but ductile in compression.

Two other important material characteristic that need to be defined at this point, as they influence our choice of material modeling, are isotropy and homogeneity. A material is said to be isotropic if its elastic properties are the same in all directions. Most engineering materials are made from crystals that are small compared to the dimensions of the entire body. These crystals are randomly oriented, so statistically the behavior of the material can be considered isotropic. Other materials, such as wood and other fibrous materials, can have similar elastic properties in two directions only (orthotropic) or in all three directions (anisotropic).

On the other hand, a material is said to be homogeneous if its elastic properties are the same throughout the body. For design purposes, most construction materials are assumed as homogeneous. This is valid even for materials like concrete that have different phases (mortar and stones), as we generally are talking about characterizing much larger volumes, which can be considered statistically homogeneous.

Tension Testing of Steel Specimens

The purpose of this experiment is:

- To acquaint students with the standard laboratory test for determining the tensile properties of metallic materials in any form (ASTM E8),

- To compare the properties of commonly used engineering metallic materials (structural steel and aluminum), and

- To compare the tested properties of metals to published values.

It will be assumed that a universal testing machine (UTM) with deformation control and associated testing and data acquisition capabilities is available. Follow recommended step-by-step procedures to perform tensile tests provided by the manufacturer of the UTM, paying particular attention to the safety guidelines. Do not proceed if you are uncertain about any step, and clarify any doubts with your lab instructor, as you can seriously injure yourself or those around you if you do not follow proper precautions. Also, make sure you know all emergency stop procedures and that you are familiar with the software running the machine.

The procedure below is generic and is meant to cover most important steps; there may be significant deviations from it depending on the available equipment.

1. Prepare Specimens:

- Obtain cylindrical test specimens for two steels, one mild and hot rolled (such as A36) and one hard and cold rolled (such as an C1018).

- Measure the diameter of the test specimen to the nearest 0.002 in. at several locations near the middle using a caliper.

- Hold the specimen firmly and mark, using a file, an approximate 2 in. gage length. Note: Mark the gage length carefully so that it is clearly etched, but not so deep as to become a stress concentration that can lead to fracture.

- Measure the actual marked gage length to the nearest 0.002 in. using a caliper.

- If possible install a strain gage as described in JoVE video on "Material Constants".

- Collect all available information on the calibration data and resolution of all instruments being used to help assess potential experimental errors and confidence limits. These two issues are key to obtaining meaningful results but are beyond the scope of what is discussed here.

2. Test the Specimens:

- Turn on the testing machine and initialize the software. Make sure that you have setup any appropriate graphing and data acquisition capabilities within the software. At a minimum, display the stress-strain curve and have displays for the load and strain.

- Select an appropriate testing procedure within the software that is compatible with the ASTM E8 testing protocol. Note the strain rate being used and whether two rates, one for the elastic and one for the inelastic range, are being used. Also, set any appropriate actions in the software (e.g., for the machine to stop at 15% strain, so as to safely remove the extensometer and to record the maximum value of load that is reached.).

- Manually raise the crosshead such that the full length of the specimen fits easily between the grips. Carefully insert the specimen into the top grips to about 80% of the grip depth; align the specimen inside the grips and tighten slightly, so as to prevent the specimen from falling. Note: DO NOT tighten the grip to its full pressure at this stage.

- Slowly lower the top crosshead. Once the specimen is within about 80% of the bottom grip depth, make sure the specimen is properly aligned within the bottom grips (i.e. with the bottom grips in their fully opened position, the specimen should "float" in the middle of the bottom grip opening). Specimen misalignment, which will result in additional flexural and torsional stresses during testing, is one of the most common errors encountered when carrying out tension tests. If the alignment is poor, work with a technician to properly align the grips.

- Apply appropriate lateral pressure to the specimen through the grips to ensure that no slipping occurs during testing. Note that there will be a small axial load at this point, as the tightening process introduces a preload into the specimen; the testing machines may have software adjustments to minimize this preload. Record the preload value.

- Attach the electronic extensometer securely to the specimen as per manufacturer's specification. Note: The extensometer blades do not need to be positioned exactly on the gage marks on the specimen, but should be approximately centered on the specimen.

- Carefully check that you have properly executed all procedures up to this point; if possible, have a supervisor verify if the specimen is ready for testing.

- Start the loading to begin applying the tensile load to the specimen and observe the live reading of applied load on the computer display. Note: If the measured load does not increase, the specimen is slipping through the grips and needs to be reattached. If this occurs, stop the test and restart again from Step 2.3.

- Sometime prior to sample failure, the test will be automatically paused without unloading the specimen. At this point, remove the extensometer. If the specimen breaks with the extensometer in place, you will destroy the extensometer, a very expensive piece of equipment.

- Resume applying tensile load until failure. Upon reaching the maximum load, the measured loads will begin to decrease. At this point, the specimen will begin necking and final fracture should occur within this necked region through ductile tearing.

- After the test is finished, raise the crosshead, loosen the top grips, and pull out the broken piece of specimen from the top grip. Once the top half of the specimen is removed, loosen the bottom grip and remove the other half of the specimen.

- Record the value at the maximum tensile load and print a copy of the stress-strain curve. Save the data recorded digitally.

- Carefully fit the ends of the fractured specimen together and measure the distance between the gage marks to the nearest 0.002 in. Record the final gage length.

- Measure the diameter of the specimen at the smallest cross section to the nearest 0.002 in.

- Document the fractured specimen with pictures and diagrams.

3. Data Analysis

- Calculate the % elongation, and reduction of area for each type of metallic material.

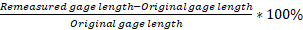

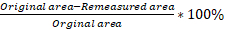

elongation =

reduction of area =

- Describe, categorize and record the predominant fracture mode for each specimen.

- Determine material properties as described in Fig. 2 and 3. Organize the data in a spreadsheet such that the strain up to 0.004 is given by the strain gage and between 0.004 and 0.15 by the extensometer (the upper limit for the extensometer is the value of strain at which it was removed from the test; this value changes depending on the deformation capacity of the specimen).

- Use the crosshead displacement and %elongation to estimate ultimate strain. If a strain gage is not used, be sure to correct for any initial slip of the extensometer. One can count squares in the graph to obtain the toughness (area under stress-strain curve).

- Using a textbook or other suitable reference, determine the elastic modulus, yield strength, and ultimate strength of the materials used. Compare the published values to the test results.

From the measurements (Fig. 5 and Table 1.), a mild steel may have elongations in the 25%-40% range, while the harder steel may be one-half of that. It is important to note that almost all the deformation is localized in a small volume and thus the %elongation is only an average; locally the strain could be much higher. Note also that the %reduction of area is also a very difficult measurement to make as the surfaces are uneven; thus this value will range considerably.

| Specimen | A36 | C1018 | in. |

| % Elongation | 33.3 | 17.3 | % |

| % Area Reduction | 54.3 | 50.1 | % |

| Tensile Yield Stress | 58.6 | 73.0 | ksi |

| Tensile Strength | 86.6 | 99.9 | ksi |

| Stress at Fracture | 58.6 | 86.7 | ksi |

| Modulus of Elasticity | 29393 | 29362 | ksi |

Table 1. Steel test summary.

Figure 4: Typical ductile (left image) and brittle (right image) failure surface.

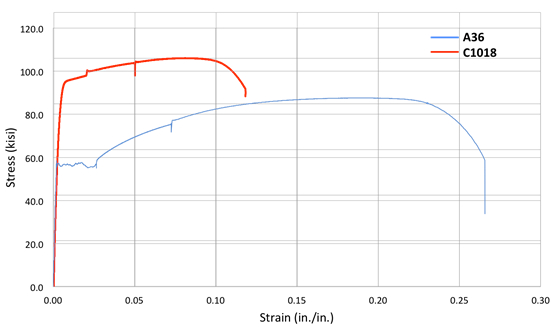

In general, these will vary from a ductile shear (cup-cone) fracture, such as would be expected from a failure such as that shown in Fig. 4, to a brittle cleavage fracture. Typical graphical results for the complete stress-strain curves are shown in Fig. 5. Note the very large differences in the stress-strain characteristic, range from a very mild but ductile A36 steel to a very strong but non-ductile C1018. Note that both are conventionally called steel, but their performance is markedly different.

Figure 5: Final stress-strain curve.

This experiment described how to obtain a stress-strain curve for typical steel. Differences in the stress-strain curves can be traced to either difference in the processing (e.g., cold working vs. hot rolling) and chemical composition (e.g., percent of carbon and other alloys). The tests showed that low-carbon steel is a very ductile material when loaded in uniaxial tension.

It is always relevant to compare experimental results to published values. The latter generally represent a minimum value from the specification based on 95% confidence limit, so it is likely that any strength value tabulated will be exceeded in the test, usually by a 5%-15% margin. However, much higher values are possible, as materials tend to be classified downwards if they do not meet some specification requirement. The strain values are generally going to be close to those published. The modulus of elasticity, on the other hand, should not vary significantly. If the value of E is not close to the published one, a through reexamination of error sources should be carried out. For example, the error may be due to slipping of the extensometer, improper calibration of the load cell or extensometer, wrong input voltages into the sensors, wrong parameters being input into the software, to name but a few.

Steel is a widely used material in the construction industry. Its applications include:

- Rolled steel I-shaped structural sections commonly used in conventional multi-story buildings because it is easy to prefabricate and connect the components, saving time in the construction process.

- Welded deep plate I-girders used in bridges, where the sections are built-up by welding deep, thin stiffened webs and thick flanges. This puts most of the material in its most useful position (the flanges), optimizing the design for strength and stiffness and reducing the overall cost of the project.

- Bolts and fasteners used in connections, where generally high strength and moderate ductility are required. These fasteners are used in myriads of products ranging from cars to household appliances.

The most important application of the tension test described herein is in the quality control process during the manufacturing of steel, aluminum and similar metals used in the construction industry. ASTM standards require that such test be run on representative samples of each heat of steel, and such results must be traceable to established benchmarks. The safety of the public is intimately tied to making sure that this type of quality control procedure is standardized and followed. Poor quality in construction materials, and lack of ductility at the material and structural level, are the most common cause of collapses during and after earthquakes and similar natural disasters. Lack of strength in critical components led to the failure of the I-35W bridge in Minneapolis in 2007 and use of substandard materials are at the root of many of the collapses that occur in developing countries, such the one that took over a thousand lives in 2013 when the Savar building collapsed in Dhaka (Bangladash).

On an everyday basis, one can cite the example of the automobile industry, which greatly benefits from knowing stress-strain behavior of steel and other materials when designing cars to perform safely and effectively in a crash situation. By designing cars that have strength in certain parts, while allowing for strain and ductility in other parts, manufacturers can create better crash management, but only if they can accurately surmise the stress-strain characteristics of each part.

Skip to...

Videos from this collection:

Now Playing

Stress-Strain Characteristics of Steels

Structural Engineering

108.7K Views

Material Constants

Structural Engineering

23.4K Views

Stress-Strain Characteristics of Aluminum

Structural Engineering

88.0K Views

Charpy Impact Test of Cold Formed and Hot Rolled Steels Under Diverse Temperature Conditions

Structural Engineering

32.1K Views

Rockwell Hardness Test and the Effect of Treatment on Steel

Structural Engineering

28.2K Views

Buckling of Steel Columns

Structural Engineering

36.0K Views

Dynamics of Structures

Structural Engineering

11.4K Views

Fatigue of Metals

Structural Engineering

40.2K Views

Tension Tests of Polymers

Structural Engineering

25.2K Views

Tension Test of Fiber-Reinforced Polymeric Materials

Structural Engineering

14.3K Views

Aggregates for Concrete and Asphaltic Mixes

Structural Engineering

12.0K Views

Tests on Fresh Concrete

Structural Engineering

25.7K Views

Compression Tests on Hardened Concrete

Structural Engineering

15.1K Views

Tests of Hardened Concrete in Tension

Structural Engineering

23.5K Views

Tests on Wood

Structural Engineering

32.8K Views

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved