JoVE Science Education

Experimental Psychology

A subscription to JoVE is required to view this content.

דיווח עצמי לעומת מדדים התנהגותיים של מיחזור

Overview

מקור: מעבדות של גארי לוונדובסקי, דייב סטרוהמץ ונטלי קירוקו - אוניברסיטת מונמאות'

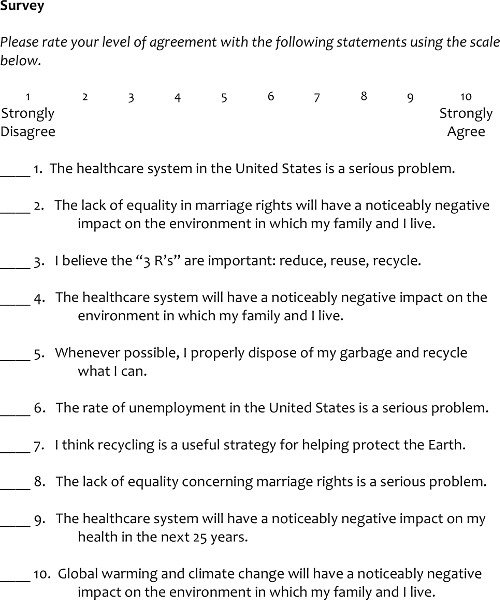

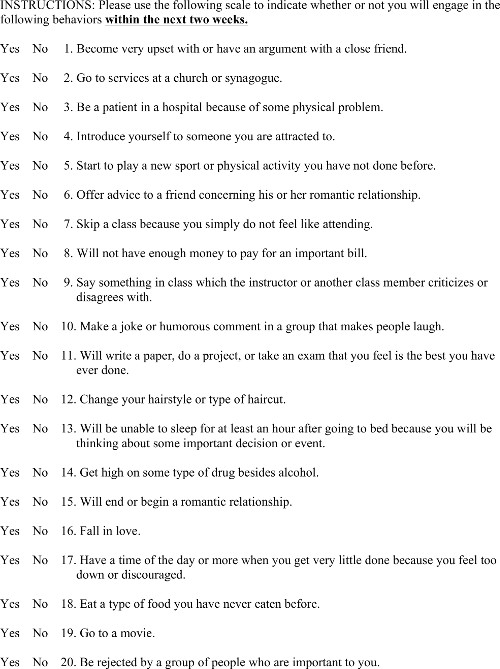

אחד האתגרים במדידת משתנה ניסיוני הוא זיהוי הטכניקה שתפיק את המדידה המדויקת יותר. הדרך הנפוצה ביותר למדוד משתנה תלוי היא דיווח עצמי – בקשת המשתתף לתאר את רגשותיו, מחשבותיו או התנהגויותיו. עם זאת, ייתכן שאנשים אינם כנים. כדי לדעת באמת משהו על משתתף, ייתכן שיהיה צורך לראות מה הם באמת עושים במצב.

סרטון זה משתמש בניסוי רב-קבוצותי כדי לראות אם תחושת קרבה לאחרים גורמת לגישות חיוביות יותר כלפי תודעה סביבתית הנמדדת הן על ידי דיווח עצמי והן על ידי התבוננות התנהגותית.

מחקרים פסיכולוגיים משתמשים לעתים קרובות בגדלים מדגמיים גבוהים יותר מאשר מחקרים במדעים אחרים. מספר רב של משתתפים מסייע להבטיח טוב יותר כי האוכלוסייה הנחקרת מיוצגת טוב יותר, כלומר,מרווח הטעות המלווה בחקר ההתנהגות האנושית נמצא מספיק. בסרטון זה, אנו מדגימים את הניסוי הזה באמצעות משתתף אחד בלבד. עם זאת, כפי שמיוצגות בתוצאות, השתמשנו בסך הכל ב-186 משתתפים כדי להגיע למסקנות הניסוי.

Procedure

1. הגדר משתני מפתח.

- צור הגדרה מבצעית (כלומר,תיאור ברור של בדיוק מה חוקר מתכוון על ידי מושג) של תחושה קרובה לאנשים.

- לצורך ניסוי זה, תחושה קרובה לאנשים כרוכה בקשר נתפס כולל תחושות של התקשרות רגשית כלפי אדם או אנשים אחרים.

- צור הגדרה מבצעית (כלומר,תיאור ברור של בדיוק מה חוקר מתכוון על ידי מושג) של תודעה סביבתית.

- לצורך ניסוי זה, התודעה הסביבתית מוגדרת כסבירותו של אדם להעריך פרקטיקות המגנות על עולם הטבע.

2. לנהל את ה

Results

הליך זה חזר על עצמו 185 פעמים, כך שהתוצאות משקפות נתונים מ-186 משתתפים בסך הכל. מספר גדול זה של משתתפים מסייע להבטיח שהתוצאות משקפות מספרים ממוצעים מדויקים של פריטים ממוחזרים. אם מחקר זה נערך באמצעות משתתפים אחד או שניים בלבד, סביר להניח כי התוצאות היו שונות בהרבה, ולא משקפות את האוכלוסייה הגד?...

Application and Summary

ניסוי רב-קבוצותי זה מראה כיצד רגשות המשתתפים הנמדדים באמצעות סקר עשויים שלא להתאים בדיוק לאופן שבו הם מתנהגים. במקרה זה, המשתתפים דיווחו על עמדות חיוביות יותר (במיוחד במצב של תחושה קרובה לאנשים), אך כשהגיע הזמן למחזר בפועל, המשתתפים לא עסקו בהתנהגות.

מחקר זה משכפל ומרחיב מחק?...

References

- Huffman, A., Van Der Werff, B. R., Henning, J. B., & Watrous-Rodriguez, K. When do recycling attitudes predict recycling? An investigation of self-reported versus observed behavior. Journal of Environmental Psychology. 382, 62-270. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2014.03.006 (2014).

- Baumeister, R. F., Vohs, K. D., & Funder, D. C. Psychology as the science of self-reports and finger movements: Whatever happened to actual behavior?. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2 (4), 396-403. doi:10.1111/j.1745-6916.2007.00051.x (2007).

- Lewandowski, G. W., Jr., & Strohmetz, D. Actions can speak as loud as words: Measuring behavior in psychological science. Social and Personality Psychology Compass. 3 (6), 992-1002. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00229.x (2009).

Tags

Skip to...

Videos from this collection:

Now Playing

דיווח עצמי לעומת מדדים התנהגותיים של מיחזור

Experimental Psychology

11.8K Views

מתיאוריה לעיצוב: תפקידה של היצירתיות בעיצוב ניסויים

Experimental Psychology

18.2K Views

אתיקה בחקר הפסיכולוגיה

Experimental Psychology

29.1K Views

ריאליזם בניסויים

Experimental Psychology

8.3K Views

פרספקטיבות על פסיכולוגיה ניסיונית

Experimental Psychology

5.6K Views

בדיקות פיילוט

Experimental Psychology

10.3K Views

מחקר תצפיתי

Experimental Psychology

13.0K Views

הניסוי הפשוט: עיצוב דו-קבוצתי

Experimental Psychology

73.1K Views

הניסוי הרב-קבוצתי

Experimental Psychology

22.7K Views

עיצוב אמצעים חוזרים ונשנים בתוך נושאים

Experimental Psychology

22.9K Views

הניסוי המגורם

Experimental Psychology

73.1K Views

אמינות בניסויים פסיכולוגיים

Experimental Psychology

8.5K Views

פלצבו במחקר

Experimental Psychology

11.6K Views

מניפולציה של משתנה בלתי תלוי באמצעות התגלמות

Experimental Psychology

8.5K Views

ניסויים באמצעות קונפדרציה

Experimental Psychology

17.8K Views

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved

We use cookies to enhance your experience on our website.

By continuing to use our website or clicking “Continue”, you are agreeing to accept our cookies.