Method Article

Mouse Model for Pancreas Transplantation Using a Modified Cuff Technique

* Wspomniani autorzy wnieśli do projektu równy wkład.

W tym Artykule

Podsumowanie

Among abdominal solid organ transplantation, pancreatic grafts are prone to develop severe ischemia reperfusion injury-associated graft damage, leading eventually to early graft loss. This protocol describes a model of murine pancreas transplantation using a non-suture cuff technique, ideally suited for analyzing these early, deleterious damages.

Streszczenie

Mouse models have several advantages in transplantation research, including easy handling, a variety of genetically well-defined strains, and the availability of the widest range of molecular probes and reagents to perform in vivo as well as in vitro studies. Based on our experience with various murine transplantation models, we developed a heterotopic pancreas transplantation model in mice with the intent to analyze mechanisms underlying severe ischemia reperfusion injury-associated early graft damage. In contrast to previously described techniques using suture techniques, herein we describe a new procedure using a non-suture cuff technique.

In recent years, we have performed more than 300 pancreas transplantations in mice with an overall success rate of >90%, a success rate never described before in mouse pancreas transplantation. The backbone of this non-suture cuff technique for graft revascularization consists of two major steps: (I) pulling the recipient vessel over a polyethylene/polyamide cuff and fixing it with a circumferential ligature, and (II) placing the donor vessel over the everted recipient vessel and fixing it with a second circumferential ligature. The resultant continuity of the endothelial layer results in less thrombogenic lesions with high patency rates and, finally, high success rates.

In this model, arterial anastomosis is achieved by pulling the abdominal aorta of the donor graft over the everted common carotid artery of the recipient animal. Venous drainage of the graft is achieved by pulling the portal vein of the graft over the everted external jugular vein of the recipient. This manuscript provides details and crucial steps of the organ recovery and organ implantation procedures, which will allow researchers with microsurgical skills to perform the transplantation successfully in their laboratories.

Wprowadzenie

Simultaneous kidney-pancreas transplantation (SPK) represents the current standard of care for patients suffering from diabetes mellitus and end stage renal disease. Successful transplantation results in long-term insulin independence associated with stabilization or even regression of diabetic microangiopathy and a better quality of life1. However, in contrast to other common solid organ transplantations, like kidney and liver transplantation, pancreatic grafts are more susceptible to ischemia reperfusion injury (IRI). Reported incidences of up to 35% jeopardize not only graft, but even patient, survival2,3.

Oxidative stress, microcirculatory disorders, increased expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and adhesion molecules resulting finally in endothelial activation and loss of its integrity, have all been attributed to this non-allogeneic graft injury4. So far, the exact molecular mechanisms of IRI are largely unknown and may vary from organ to organ.

Despite major progress utilizing in vitro models, the development of animal models is crucial to deepen the knowledge of molecular mechanisms involved in IRI-associated graft alterations following pancreas transplantation. Several pancreas transplantation models have been developed in rodents5,6, but only one is reported in mice7. The Achilles heel of this highly demanding microsurgical procedure is the low survival rate of 46%. However, mouse models represent the best model for transplant-related research, since the widest variety of molecular analysis tools can be applied to them. Based on extensive microsurgical experience in mice with different organ transplantations8,9,10, we developed a new, highly reproducible technique for heterotopic, cervical pancreas transplantation in mice with >90% success rate using a non-suture cuff technique. With this technique, anastomoses-related complications are reduced to a minimum, and a high success rate can be achieved compared to the suture model11. So far, only one mouse model with similar success rates has been described by Liu et al12. However, there are no studies published using this model so far.

Protokół

In order to avoid alloimmune responses, and to strictly investigate ischemia reperfusion injury-related graft damage, a syngeneic donor-recipient pair should be used. In this protocol, male C57BL6 (H2b) 10-12-week-old mice weighing 26 to 28 g were used as size-matched donor-recipient pairs. All animals were housed in a barrier pathogen free facility and received human care in compliance with the "Principals of Laboratory Animal Care" formulated by the National Society for Medical Research and the "Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals" prepared by the National Academy of Sciences and published by the National Institutes of Health (NIH Publication no. 86-23, revised 1985). The Austrian Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture approved the experiments described in this manuscript (BMWF-66.011/0056-II/3b/2011).

1. Pancreas Procurement

- Anesthetize the donor animal with an intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection of xylazine (5 mg/kg body weight) and ketamine (100 mg/kg body weight) using a 27-gauge (G) needle.

- Shave the hair in the abdominal region using an electrical shaver, and fix the mouse on the operative field in a supine position with strands of tape.

- Scrub the operative field three times with chlorhexidine-soaked gauzes.

- Perform a midline abdominal incision with a bilateral subcostal extension using scissors. Gently exteriorize the viscera to the left with sterile cotton sticks, and wrap them in a moistened gauze. Lift the xyphoid cranially with a mosquito clamp to provide maximal exposure of the abdominal cavity for the following steps.

- Using a 19 G needle, inject 400 µL of a sterile 1:4 heparin-sodium chloride solution for heparinisation into the inferior vena cava (IVC). After removing the needle, euthanize the animal by exsanguination transecting of the aorta.

- Dissect the abdominal aorta between the origin of the superior mesenteric artery and the right renal artery by gently separating the fibrous tissue using curved tip forceps. Undermine the aorta and tie it with an 8/0 silk ligature.

- Identify the hepatoduodenal ligament, which runs between the postpyloric duodenum and the liver hilum. Divide the bile duct below the entrance of the cystic duct after distal ligature, and gently dissect and transect the portal vein as distally as possible to have enough length for performing the anastomosis in the recipient.

- Using curved tip forceps, bluntly dissect the abdominal aorta starting from the previous ligature (see step 1.6). Undermine the periaortic tissue using curved tip forceps, tie it with an 8/0 silk ligature, and transect it with scissors.

- Using bipolar forceps, coagulate all its lumbar branches and transect the aorta with scissors as closely as possible to the diaphragm, in order to provide enough length for vessel anastomosis. At last, transect the already tied aorta above the left renal artery.

- Perfuse the pancreas with a 19 G syringe with 5 mL of 4 °C histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate perfusion solution in an antegrade fashion via the abdominal aorta, until there is a clear effluent coming from the portal vein. Apply low pressure to avoid oedema formation.

NOTE: Perform Steps 1.5 to 1.9 in a fast and standardized fashion to avoid any bias by warm ischemic deterioration of the recovered graft. - Replace the viscera into the peritoneal cavity using sterile cotton sticks.

- Using curved tip forceps, separate the pancreas stepwise starting from the postpyloric duodenum, and moving forward until reaching the ligament of Treitz. For these steps, identify avascular connective tissue areas between the pancreas and the duodenal wall.

- Bluntly dissect these areas using curved tip forceps in order to isolate bridging vessels between the pancreas and the duodenum. Pass an 8/0 silk ligature around each isolated vascular structure and tie it.

- Finally, transect the vascular structure with scissors towards the duodenal wall. In the same fashion, use an 8/0 silk suture to separate the pancreas from the mesentery, the transverse colon, and the stomach.

NOTE: During this procedure, the choledocho-pancreatic duct is ligated.

- Identify the gastrosplenic ligament running from the spleen to the stomach, and the short gastric branches, by lifting the stomach cranially and cutting it with scissors. Leave the spleen attached to the recovered graft.

NOTE: In order to minimize graft rewarming, irrigate the pancreas continuously using a 10 mL syringe with a 19 G needle with the cold histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate perfusion solution stored on ice. - Finally, remove the pancreas from the donor site (Figure 1B) by grasping the spleen with forceps, and transfer it into the recipient.

- Alternatively, to trigger severe ischemia reperfusion injury, store the graft in sterile, 4 °C perfusion solution for 16 h before implanting it into the recipient animal.

2. Recipient Preparation

- Anesthetize the recipient animal with an i.p. injection of xylazine (5 mg/kg body weight) and ketamine (100 mg/kg body weight) using a 27 G needle.

- Shave the right lateral cervical region using an electrical shaver, and place the mouse on the operative field in a supine position. Fix the mouse using strands of tape. Avoid overstretching the front limbs to avoid compromising respiration.

- Scrub the operative field three times using chlorhexidine-soaked gauzes.

- Make a right paramedian, slightly oblique skin incision from the jugular incision to the right mandible angle.

- Bluntly identify and mobilize the lateral branches of the right external jugular vein. Coagulate them with bipolar forceps and transect them with scissors.

- Lift the right lobe of the submandibular salivary gland cranially, identify the vascular pedicle, and cauterize it using bipolar forceps. Remove the lobe by transecting the cauterized pedicle with scissors.

- In analogy to step 2.5, identify all medial branches of the external jugular vein, cauterize them with bipolar forceps and transect them with scissors. Undermine the external jugular vein with curved tip forceps as cranially as possible, and ligate it with two 8/0 silk ligatures, leaving enough space between the ligatures.

- Transect the external jugular vein between the two previously placed ligatures with straight scissors.

- Pass the proximal end of the external jugular vein through the polyethylene cuff (inner diameter of 0.75 mm, outer diameter of 0.94 mm), and fix the handle of the cuff with a venous microhemostat clamp.

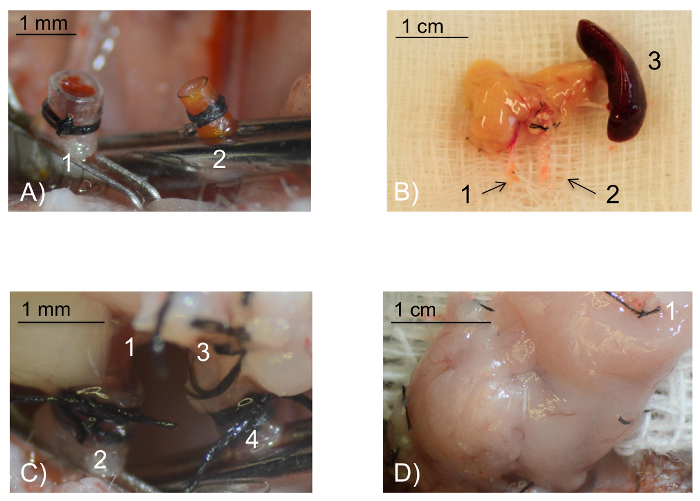

- Remove the tie at the end of the vessel stump and evert the vessel over the cuff. Fix the everted vein on the cuff with a circular 8/0 - silk ligature (Figure 1A).

- Proximally and distally cauterize the superficial part of the right sternocleidomastoid muscle, transect it with scissors, and remove it.

- Gently mobilize the common carotid artery, undermine it below the bifurcation, and ligate it twice, making sure not to tie the carotid bifurcation. Cut the vessel between the ties.

- Similar to step 2.9, pass the proximal end of the common carotid artery through the polyamide cuff (inner diameter of 0.57 mm, outside diameter of 0.6 mm), and fix it with an arterial microvascular clamp.

- Remove the ligature at the end of the vascular stump, and gently widen the lumen using vessel dilatators. Evert the vessel over the arterial cuff, and fix it with an 8/0 silk ligature (Figure 1A).

3. Implantation

- Place the graft into the recipient's neck region using the spleen as a handle, with the head oriented laterally, the tail including the spleen medially, and the vessel stumps ventro-caudally. Use cotton sticks to position the graft properly.

- Gently pull the portal vein of the pancreatic graft over the recipient animal's external jugular vein, which has been previously everted, and fixed on the appropriate cuff (see step 2.10). Fix it with a circular 8/0 silk ligature.

- Pull the stump of the abdominal aorta of the graft over the everted common carotid artery of the recipient animal. Fix it with a circumferential 8/0 silk ligature (Figure 1C).

- Identify the splenic vessels close to the hilum of the spleen, and undermine them with curved tip forceps. Tie them with 8/0 silk ligatures and transect the splenic vessels to remove the spleen. Finally, shorten the ties.

- Using a clamp applying forceps, remove the clamp on the venous cuff first. Then remove the arterial clamp.

NOTE: If transplantation was successful, the pancreatic graft will be reperfused immediately showing a homogeneous pinkish color and visible arterial pulsation (Figure 1D). - Moisten the graft with normothermic saline solution.

- Remove the handle of the venous cuff using straight forceps.

- Close the surgical wound with a running 6/0 suture.

4. Postoperative Care (Endpoint)

- Following the procedure, apply up to 0.5 mL of normal saline subcutaneously (s.c.) for replacement of intraoperative fluid loss using a 19 G needle.

- Keep the recipient animal on a heating pad until complete recovery from anaesthesia.

- Once awake, return the recipient animal to the housing facility, where it can have food and water ad libitum.

- To prevent postoperative pain, administer right after the operation (1) Buprenorphin (0.1 mg/kg b.w.) every 12 h for the first 5 days and (2) carprofen 4 mg/kg b.w. every 12 h s.c. for the first week.

- In order to estimate proper nutritional intake, monitor weight (g) of each recipient animal every day. A weight loss of more than 10-15% compared to weight at surgery day, apathy, crippling, a very bent back, as well as surgical side infections represent endpoints.

- In this case, as well as after reaching clinical endpoint, sacrifice the animal using terminal isoflurane inhalation.

Wyniki

Over the last decade, we performed more than 300 pancreas transplantations in mice. After establishing the protocol, there was an overall survival of >90%. Postoperative bleeding was the main cause for failure, followed by graft thrombosis with subsequent lethal necrotic graft pancreatitis. In both cases, endpoints were reached within 24 h and animals were sacrificed. There were not any neurological disorders, symptoms such as dysphagia, and surgical side infections in this series.

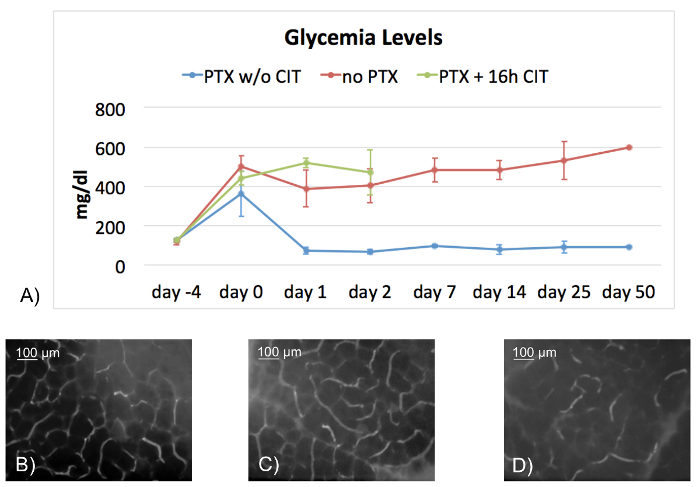

To investigate the endocrine function of the transplanted grafts, and hence validate the patency of the model, hyperglycemia was induced in recipient mice by pre-treatment with a single dose of intraperitoneally applied streptozotocin (312.5 mg/kg body weight) 4 days before surgery. Mice were considered hyperglycemic if blood glucose levels were >300 mg/dL. Figure 2A shows the blood glucose levels of different groups. Mice receiving grafts without a prolonged cold ischemia time of 16 h reached normogylcemia within 24 h following transplantation, and maintained this metabolic state over the entire observation period. In contrast, non-transplanted animals remained hyperglycemic. Since we were interested in the impact of ischemia reperfusion injury-associated graft damage on endocrine function, we added a third group where grafts were exposed to 16 h prolonged cold ischemia time (CIT) and 45 min of warm ischemia time (WIT). Mice receiving these grafts did not reach normoglycemia and had to be sacrificed after 48 h due to the development of severe pancreatitis, which was shown to be lethal in this model13.

This model is useful for various projects aimed at investigating ischemia reperfusion injury-associated early graft damage. Further investigations included, among others, confocal intravital fluorescence microscopy for quantification of microcirculatory derangements performed 2 h following transplantation. Contrast of the grafts' microvessels was enhanced by injecting 0.3 mL of a 0.4% fluorescein-isothiocyanate-labeled dextran (MW 150 000) into the penile vein. Figure 2B displays a regular capillary pattern of a naïve murine pancreas and of a transplanted pancreatic graft, which was not exposed to prolonged CIT (Figure 2C). In contrast, Figure 2D shows the breakdown of the microcirculation as a result of exposing the pancreatic graft to prolonged CIT.

Figure 1: Intraoperative pictures. (A) Intraoperative view of the recipient vessels prepared for anastomosis. The external jugular vein (1) has been everted over the venous polyethylene cuff and fixed with a circular 8/0 silk ligature. In analogy, the common carotid artery (2) has been everted and fixed over the smaller arterial polyamide cuff. Scale bar 1 mm. (B) The pancreatic graft ex situ. The portal vein (1) and the stump of the abdominal aorta (2) needed for vascular anastomosis. The spleen (3) is retrieved together with the pancreas and is used as a handle. The spleen will be removed before reperfusion of the graft. Scale bar 1 cm. (C) Intraoperative view of the anastomoses. The portal vein (1) is pulled over the cuff of the everted external jugular vein (2) and fixed with a circular 8/0 silk tie. Similarly, the aortic stump of the abdominal aorta (3) is pulled over the cuff of the everted common carotid artery (4). Scale bar 1 mm. (D) Intraoperative view of the perfused pancreatic graft following 5 min reperfusion: After removal of the vein, followed by the arterial clamp, a successfully transplanted pancreatic graft displays a homogenous pinkish color. The spleen has been removed before reperfusion (1: ligated splenic vessel). Scale bar 1 cm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Endocrine function of the pancreatic graft and confocal in vivo fluorescence microscopy. Figure 2A shows a line chart with blood glucose levels of transplanted mice without CIT (n = 10, PTX w/o CIT, blue line), non-transplanted mice (n = 11, no PTX, red line), and mice receiving grafts exposed to prolonged CIT (PTX + 16 h CIT, n = 10, green line). All recipients were previously rendered hyperglycemic with 312.5 mg/kg b.w. streptozotocin i.p. While all recipients of grafts without CIT were able to survive the entire observation period (50 days) with intact endocrine function, non-transplanted mice remained hyperglycemic over the entire observation period. Mice receiving grafts exposed to 16 h CIT did not recover from hyperglycemia and had to be sacrificed 48 h after transplant surgery, due to weight loss of more than 10-15%. Mice surviving the entire observation period were sacrificed at day 50 following one last glycemia measurement. Microcirculation in transplanted grafts was assessed by confocal intravital fluorescence microscopy 2 h following transplantation. Naïve pancreas served as controls. Figure 2B shows a regular capillary pattern in the naïve pancreas. A regular capillary mesh is also seen in transplanted grafts not subjected to prolonged CIT (Figure 2C). In contrast, a breakdown of the microcirculation is observed in transplanted grafts exposed to prolonged CIT (Figure 2D). Scale bar 100 µm. Data in the graph are expressed as ± Standard Deviation. PTX: pancreas transplantation; CIT: cold ischemia time; w/o: without Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Dyskusje

IRI-associated graft damage is inherent to solid organ transplantation, and it is characterized by a disturbance of the microcirculation. Accumulation of several metabolites during the ischemic phase, and initiation of inflammatory cascades mediated mainly by reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, results in tissue damage during graft reperfusion4. This cascade may jeopardize not only short-term, but also long-term success and, hence, significantly influences patients survival14. To date, combined kidney pancreas transplantation represents the therapy of choice for patients suffering from type 1 diabetes with end stage renal disease15. Several studies have shown that a successful combined kidney pancreas transplantation does not only restore and protect kidney graft function in diabetic recipients, but also stabilizes or even reverses secondary complications, including neuropathy as well as micro- and macroangiopathy16,17,18.

Despite continuous efforts in Reduction, Replacement, and Refinement (3 R's) in animal research, reproduction of complex pathophysiological processes like IRI is merely impossible in in vitro settings. Therefore, animal models are still considered to be the ideal tool for translational research19,20. Mouse models like the one described here have several advantages compared to rat or other animal models. These include the availability of a vast quantity of genetically well-defined inbred mouse strains (e.g. transgenic and knock-out strains), a plethora of molecular analysis tools, as well as an easy and cheap handling21. A major advantage of the described model lies in the non-suture cuff technique. By using the herein presented technique, success rates of >90% are achievable, which is dramatically better compared to previously described models22. Using this non-suture technique, we significantly reduced common complications like hypovolemic shock, thrombosis, and stenosis of the anastomoses12. A further advantage of this method consists of the extra abdominal position of the graft, which is associated with rapid postoperative recovery of the recipient. Additionally, the cervical location makes it perfectly suitable for in vivo analyses, such as live imaging of the graft by exterioration without any tension22.

The main drawback of this model is the occlusion of the pancreatic duct, which does not resemble clinical reality. In this model, exocrine drainage is managed by tying the choledocho-pancreatic duct. In the long term, this results in a marked fibrosis and atrophy of the gland without leading to graft pancreatitis22. Due to this deterioration of the exocrine tissue, which we observed as early as at day 30 after transplantation, we believe that this model is not suited for long term observation. In contrast, the unimpaired endocrine function makes gylcemic controls of the recipient an easy tool for daily assessment of the function of the graft13,23,24.

These characteristics makes this an ideal model for analyzing early graft injuries associated with long preservation periods or with different preservation solutions and techniques. To achieve optimal success with this model, several crucial steps must be considered. The pancreas itself is very susceptible to manipulation. Therefore, gentle handling using cotton sticks during organ recovery and during implantation minimizes mechanical trauma. Direct grasping of the gland with forceps should be avoided, since it would inevitably result in severe graft damage. For the same reason, the spleen is recovered together with the pancreas, and is used as a handle. This is also established in clinical practice. A further pitfall involves cold perfusion, which is achieved by perfusion via the aortic stump by using 4 °C histidine-tryptophan-ketoglutarate perfusion solution. Hereby, an excessive swelling of the gland can be avoided by gently perfusing the graft. The remaining perfusion solution should be used for moistening the graft, in order to keep its temperature low during organ recovery.

With regard to recipient preparation a careful dissection of both the external jugular vein as well as the common carotid artery sets the base for successful revascularisation. In particular, complete exposure of the vein by removing not only all tributaries, but also the surrounding fat tissue, is necessary in order to avoid external compression and stenosis by remaining fat tissue. The selection of the appropriate cuff diameters is crucial. Based on shared experience, for mice weighing between 25 to 28 g, an inner diameter of 0.57 mm for the arterial cuff, and between 0.75 and 0.8 mm for the venous cuff, is appropriate. Precise, clean cutting of the edges of the cuffs is mandatory to avoid tearing the vessel stump. Dilatation of the vessels, especially of the artery, is achieved best by using vessel dilatators with fine tips. As a rule of thumb, the vessel should be able to widen to twice the lumen of the cuff. During the process of everting the vessel over and fixing it on the cuff, we recommend stabilizing vascular clamps by placing them under a skin flap, as this eases this crucial step.

As already mentioned, the non-suture cuff-technique represents an easy method for vascular anastomosis and can be performed within 5 min. However, correct positioning of the graft in the recipient's neck region is of utmost importance for correct revascularization. Hereby, the final correct positioning of the graft in the neck region has to be anticipated in order to allow a safe, straight, and tension-free anastomosis of both the vein and the artery. Vessels that are too long have to be avoided, since this may lead to outflow obstruction due to kinking. For the same reason, the cuff-handle at the venous anastomosis should also be removed following reperfusion. In cases of localized bleedings from the pancreatic graft, successful hemostasis can be achieved by gently compressing the bleeding side for 5 min using cotton sticks. This is the only successful way to manage this kind of complication. Cauterization, even though highly selective, resulted in graft loss in almost all cases, due to necrotic pancreatitis.

In summary, we developed a method for pancreas transplantation in mice using a non-suture cuff technique, which is technically and microsurgically feasible and has excellent success rates. Given the progredient fibrosis of the pancreas due to the duct occlusion, this model is suited best for research areas focusing on early graft damages. This manuscript is intended to allow researchers to safely establish this model in their laboratories.

Ujawnienia

The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests.

Podziękowania

This work was supported by grants #2008-1-596 and #UNI-0404/1956 of the "Tiroler Wissenschaftsfonds (TWF)" (https://www.tirol.gv.at/en/), and by grant #2013-042018 of the "MUI-Start Förderungsprogramm" of the Medical University Innsbruck.

Materiały

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Adventitia Scissors | S&T | S-00102 | Straight |

| Dumont # 7 Forceps | FST | 11271- 30 | Curved Tip 0.17 x 0.1 mm |

| Yasargil Clip Mini Permanent 7mm | Aesculap | FE720K | |

| Micro vessel clip | S&T | B1 00396 V | |

| Vessel dilatator | S&T | D-5a.2, 00125 | |

| Clip applier | S & T | CAF-4 00072 | for venous cuff |

| Clip applier | Aesculap | FE572K | for the arterial cuff |

| Polyethylene tube | Portex Ltd | Inner diameter 0.75 mm for venous cuff | |

| Polymide tubing | Vention Medical | 141-0051 | Inner diameter 0.8 mm (Alternative for polyethylene tube from Portex Ltd) |

| Polymide tubing | Vention Medical | 141-0033 | Inner diameter 0.57 mm for arteriail cuff |

| Bipolar forceps | Micromed | 140-100-015 | |

| 8/0 silk ligatures | Catgut GmbH, Merkuramed | 17209008 | |

| Custodiol HTK solution | Dr. Franz Köhler Chemie | 59997 | |

| Ketamin Graeub | aniMedica GmbH | 32554 | |

| Xylasol Graeub | aniMedica GmbH | 50855 |

Odniesienia

- Gruessner, A. C. 2011 update on pancreas transplantation: comprehensive trend analysis of 25,000 cases followed up over the course of twenty-four years at the International Pancreas Transplant Registry (IPTR). Rev Diabet Stud. 8 (1), 6-16 (2011).

- Troppmann, C. Complications after pancreas transplantation. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 15 (1), 112-118 (2010).

- Fernández-Cruz, L., et al. Native and graft pancreatitis following combined pancreas-renal transplantation. Br J Surg. 80 (11), 1429-1432 (1993).

- Eltzschig, H. K., Eckle, T. Ischemia and reperfusion-from mechanism to translation. Nat Med. 17 (11), 1391-1401 (2011).

- Konigsrainer, A., Habringer, C., Krausler, R., Margreiter, R. A technique of pancreas transplantation in the rat securing pancreatic juice for monitoring. Transpl. Int. 3 (3), 181-182 (1990).

- Lee, S., Tung, K., Koopmans, H., Chandler, J., Orloff, M. Pancreaticoduodenal transplantation in the rat. Transplantation. 13 (4), 421-425 (1972).

- Tori, M., Ito, T., Matsuda, H., Shirakura, R., Nozawa, M. Model of mouse pancreaticoduodenal transplantation. Microsurgery. 19 (2), 61-65 (1999).

- Oberhuber, R., et al. Murine cervical heart transplantation model using a modified cuff technique. J Vis Exp. (92), e50753 (2014).

- Brandacher, G., et al. Tetrahydrobiopterin compounds prolong allograft survival independently of their effect on nitric oxide synthase activity. Transplantation. 81 (4), 583-589 (2006).

- Zou, Y., Brandacher, G., Margreiter, R., Steurer, W. Cervical heterotopic arterialized liver transplantation in the mouse. J Surg Res. 93 (1), 97-100 (2000).

- Zhou, Y., Gu, X., Xiang, J., Qian, S., Chen, Z. A comparative study on suture versus cuff anastomosis in mouse cervical cardiac transplant. Exp Clin Transplant. 8 (3), 245-249 (2010).

- Liu, X. Y., Xue, L., Zheng, X., Yan, S., Zheng, S. S. Pancreas transplantation in the mouse. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 9 (3), 254-258 (2010).

- Maglione, M., et al. Donor pretreatment with tetrahydrobiopterin saves pancreatic isografts from ischemia reperfusion injury in a mouse model. Am J Transplant. 10 (10), 2231-2240 (2010).

- Drognitz, O., Obermaier, R., von Dobschuetz, E., Pisarski, P., Neeff, H. Pancreas transplantation and ischemia-reperfusion injury: current considerations. Pancreas. 38 (2), 226-227 (2009).

- White, S., Shaw, J., Sutherland, D. Pancreas transplantation. Lancet. 373 (9677), 1808-1817 (2009).

- Morath, C., et al. Simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplantation in type 1 diabetes. Clin Transplant. 23 (Suppl 21), 115-120 (2009).

- Perseghin, G., et al. Cross-sectional assessment of the effect of kidney and kidney-pancreas transplantation on resting left ventricular energy metabolism in type 1 diabetic-uremic patients: a phosphorous-31 magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 46 (6), 1085-1092 (2005).

- Secchi, A., Caldara, R., La Rocca, E., Fiorina, P., Di Carlo, V. Cardiovascular disease and neoplasms after pancreas transplantation. Lancet. 352 (9121), 65 (1998).

- Kirk, A. D. Crossing the bridge: large animal models in translational transplantation research. Immunol Rev. 196, 176-196 (2003).

- de Jong, M., Maina, T. Of mice and humans: are they the same?--Implications in cancer translational research. J Nucl Med. 51 (4), 501-504 (2010).

- Niimi, M. The technique for heterotopic cardiac transplantation in mice: experience of 3000 operations by one surgeon. J Heart Lung Transplant. 20 (10), 1123-1128 (2001).

- Maglione, M., et al. A novel technique for heterotopic vascularized pancreas transplantation in mice to assess ischemia reperfusion injury and graft pancreatitis. Surgery. 141 (5), 682-689 (2007).

- Cardini, B., et al. Crucial role for neuronal nitric oxide synthase in early microcirculatory derangement and recipient survival following murine pancreas transplantation. PLoS One. 9 (11), e112570 (2014).

- Maglione, M., et al. Prevention of lethal murine pancreas ischemia reperfusion injury is specific for tetrahydrobiopterin. Transpl Int. 25 (10), 1084-1095 (2012).

Przedruki i uprawnienia

Zapytaj o uprawnienia na użycie tekstu lub obrazów z tego artykułu JoVE

Zapytaj o uprawnieniaThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone