Murine Hind Limb Long Bone Dissection en Bone Marrow Isolation

In This Article

Summary

Here we present a protocol for the dissection of hind limb long bones (femurs and tibiae) from the laboratory mouse. We further describe a rapid technique for bone marrow isolation from these bones that utilizes centrifugation for removal of bone marrow from the bone marrow space.

Abstract

Investigation of the bone and the bone marrow is critical in many research fields including basic bone biology, immunology, hematology, cancer metastasis, biomechanics, and stem cell biology. Despite the importance of the bone in healthy and pathologic states, however, it is a largely under-researched organ due to lack of specialized knowledge of bone dissection and bone marrow isolation. Mice are a common model organism to study effects on bone and bone marrow, necessitating a standardized and efficient method for long bone dissection and bone marrow isolation for processing of large experimental cohorts. We describe a straightforward dissection procedure for the removal of the femur and tibia that is suitable for downstream applications, including but not limited to histomorphologic analysis and strength testing. In addition, we outline a rapid procedure for isolation of bone marrow from the long bones via centrifugation with limited handling time, ideal for cell sorting, primary cell culture, or DNA, RNA, and protein extraction. The protocol is streamlined for rapid processing of samples to limit experimental error, and is standardized to minimize user-to-user variability.

Introduction

The study of long bones and the cells of the bone marrow is central to a myriad of research disciplines, including, but not limited to, bone biology, cancer biology, immunology, hematology, and biomechanics. The bone is a highly dynamic organ that together with the cartilage forms the skeleton to provide mechanical support against loading and protection of the internal organs. In addition, the mineral components of bone are a storage sink for the critical signaling molecules calcium and phosphorus, as well as other factors1. Finally, bones house the bone marrow and, together with metabolically active bone forming osteoblasts and bone resorbing osteoclasts, provide the stem cell niche necessary for the maintenance of hematopoietic and lymphoid cell populations.

Bone and bone marrow are affected in many disorders, often leading to bone marrow dysfunction, severe bone pain, and pathologic fracture. Bone is a common site of metastasis in many solid tumors, most notably breast cancer and prostate cancer, where tumor cells directly engage the bone marrow niche to initiate the vicious cycle of bone metastasis and displace hematopoietic stem cells2,3. Hematopoietic malignancies including myeloma and leukemia are characterized by bone marrow dysfunction as well as deregulation of healthy bone remodeling1. Other non-malignant skeletal disorders are also active areas of research, such as osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, scoliosis, and rickets. Even in an otherwise healthy individual, biomechanical failure in a bone leads to a painful fracture. All of these disorders represent active areas of research with the goal of identifying new preventative measures and treatment regimens to reduce morbidity and mortality.

To research the plethora of roles of the bone and the bone marrow, both under physiologic and pathologic conditions, it is critical for researchers to have a simple and efficient standardized method for dissection of the mouse long bones for rapid processing of large in vivo experiments. The dissection protocol outlined here is suitable for all long bone analyses including ex vivo imaging, histology, histomorphometry, and strength testing, among others. Similarly, a standardized bone marrow isolation method with high bone marrow cell recovery and low inter-user variability is important for experimental analysis such as fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or quantitative PCR (qPCR) as well as downstream applications such as primary cell culture of bone marrow cells.

Protocol

Alle dierlijke werk werd in overeenstemming met de in de Guide geschetst voor de zorg en het gebruik van proefdieren van de National Institutes of Health aanbevelingen goedgekeurd door de Institutional Animal Care en gebruik Comite.

1. Hind Limb Long Bone Dissection

- Euthanaseren de muis in overeenstemming met de institutionele richtlijnen.

- Plaats de muis in een liggende positie en bevestig door pinning alle vier de poten door de muis voetzooltjes onder het enkelgewricht.

- Spuit de muis met 70% ethanol, goed dousing de benen.

- Maak een kleine incisie aan de rechterkant van de middellijn in de onderbuik, net boven de heup.

- Verleng de incisie langs de been en langs het enkelgewricht.

- Trek de huid en snijd de quadriceps spieren verankerd aan proximaal uiteinde van het femur op de voorste zijde van het dijbeen bloot te leggen en pin uit het been, het plaatsen van de pen in een hoek van 45 graden van het bord.

- Met het blade van de schaar tegen de dorsale zijde van het dijbeen, snijd de hamstrings van het kniegewricht.

- Trek de huid en de hamstrings verankerd aan het proximale einde van het dijbeen naar de achterste zijde van het dijbeen bloot te leggen en pin uit het been, het plaatsen van de pen in een hoek van 45 graden van het bord.

- Met de tang, houdt het distale uiteinde van het femur, net boven het kniegewricht. Leid de bladen van de schaar op beide zijden van de femorale schacht naar het heupgewricht, zorg dat in de femur zelf te snijden.

- Na het bereiken van de heupkop, aangegeven door de schaar iets openen, draai de schaar met het bovenblad van de schaar bewegen direct over de heupkop naar het dijbeen ontwrichten, en let op het bot onder de heupkop niet te breken.

- Pak de bovenkant van de femorale as met de tang, snijd het zachte weefsel weg van de femurkop om deze uit het acetabulum.

- Trek de hele been bot, met inbegripfemur, knie en scheenbeen, en weg van het lichaam, zorgvuldig wegsnijden van het bindweefsel en spieren verbinden het been aan de huid.

- Soms gedwongen het enkelgewricht en weer gebruik maken van de schaar in een draaiende beweging aan het scheenbeen ontwrichten.

- Grijpen de distale einde van het scheenbeen, zorg ervoor dat u de pezen verbreken, trekt u de tibia omhoog en weg van het lichaam en het prikbord.

- Snijd de resterende bindweefsel vastmaken van het pijpbeen de muis bij de knie.

- Verwijder extra spier- of bindweefsel bevestigd aan het femur en de tibia.

- Voor alle toepassingen die het been nodig hebben om intact (histologie, histomorfometrie, biomechanische testen, enz.) Blijven doorgaan met standaard in-house protocollen (zoals in 4-7). Beenmerg te isoleren, gaat u verder met deel 2.

2. Lange Bone Voorbereiding van Bone Marrow Isolation

- Met behulp van de tang, pakt het dijbeen met de knieschijf afgekeerd eennd het proximale einde (heupkop) naar beneden.

- Soms gedwongen het kniegewricht en gebruik de schaar in een draaiende beweging van de tibia en femur ontwrichten.

- Snijd elke bindweefsel houdt het bovenbeen en onderbeen samen.

- Met behulp van de tang, pakt het dijbeen met de voorste afgekeerde zijde en het proximale uiteinde (heupkop end) naar beneden.

- Leid de schaar de femurschacht aan de condylen.

- Voorzichtig draai de schaar heen en weer naar de knobbels, de knieschijf te verwijderen, en de epifyse naar de metafyse bloot te leggen.

- Verwijder extra spier- of bindweefsel bevestigd aan het femur via forceps, scharen en Kimwipes.

- Met behulp van de tang, pak de tibia met de voorste afgekeerde zijde en het distale einde (enkel end) naar beneden.

- Als het scheenbeen epiphysis intact is, begeleiden de schaar de tibia schacht naar de condylen.

- Voorzichtig draai de schaar heen en weer om de knobbels te verwijderen en epifyse naar de metaph bloottion.

- Verwijder extra spier- of bindweefsel aan de tibia behulp forceps, scharen en Kimwipes.

3. Bone Marrow Isolation

- Duw een 18 G naald door de bodem van een 0,5 ml microcentrifugebuis.

- Plaats de lange botten (maximaal 2 scheen- en 2 tibiae) in de buis, knie-end naar beneden eind naar beneden en sluit het deksel.

- Nest de 0,5 ml microcentrifugebuis in een 1,5 ml microcentrifugebuis.

- Centrifugeer de buizen bij geneste ≥10,000 xg in een microcentrifuge 15 seconden.

- Controleer of het beenmerg is gekomen uit de botten werden gesponnen door visuele inspectie. De botten moeten verschijnen wit en er moet een grote visuele pellet in de grotere buis.

- Gooi de 0,5 ml microcentrifugebuis met de beenderen.

- Suspendeer het beenmerg in geschikte oplossing (bijvoorbeeld PBS, kweekmedia FACS buffer) en vult experimentele protocol (DNA, RNA of eiwit isolatie,FACS-analyse, of primaire celkweek).

Representative Results

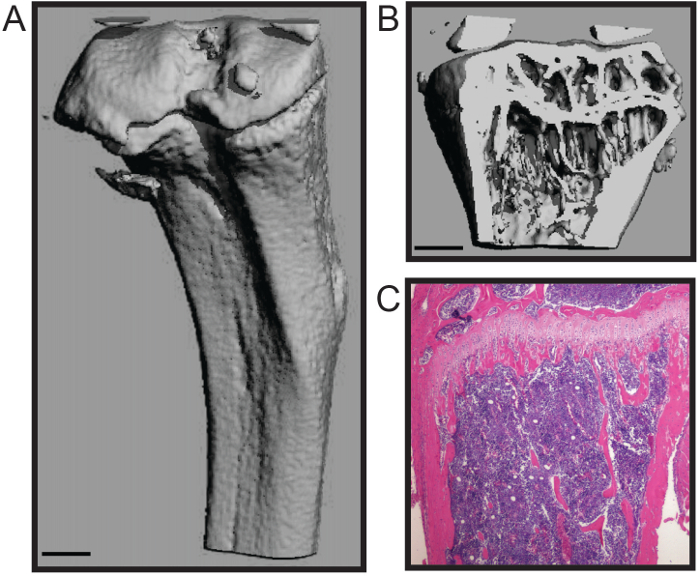

De hier beschreven protocol geoptimaliseerd voor snelle ontleding van de muis femur en tibia met minimale schade aan het botweefsel. Deze techniek is geschikt voor een aantal downstream analyses, waaronder biomechanica studies, histomorfometrie (Figuur 1 A - B) en histologie (figuur 1C) 4,7. De representatieve histomophometric micoCT 3D reconstructie (Figuur 1 A - B) toont aan dat zowel de poreuze bot en corticale mantel worden gesteld dat een accurate kwantificering van de gestandaardiseerde structurele parameters voor bothistomorfometrie, zoals trabeculaire aantal, dikte en afstand; volume bot; en corticale dikte, naast andere maatregelen 8. De vertegenwoordiger histologisch deel toont een H & E gekleurde formaline gefixeerde en ontkalkt tibia (figuur 1C). De afbeelding toont de integriteit van zowel de verkalkte béén en cellulaire beenmerg voor histologische analyse.

Het beenmerg isolatie procedure behoudt de steriliteit van het beenmerg ruimte, heeft een lage handling ter beperking van verontreiniging, en doet het snijden van de lange bot niet nodig, waardoor het verlies van beenmerg opbrengst verminderen. Het beenmerg is geschikt voor vele verdere toepassingen, waaronder flowcytometrie 5 en PCR-analyses. Bovendien kan deze werkwijze worden gebruikt om beenmerg te primaire celkweek van beenmergcellen, waaronder osteoclasten en osteoblasten (Figuur 2A - B) isoleren 4,6.

Figuur 1. Histomorfometrische en histologische analyses van muis pijpbeen. Driedimensionale microCT reconstructie van een muis tibia toont (A) de buitenste corticale schil en (B trong>) trabeculair bot (schaal bar = 0,5 mm). (C) histologische H & E kleuring van een ontkalkt en deelbaar tibia (4x). Afbeeldingen met dank aan Katherine Weilbaecher, Washington University School of Medicine, USA. Klik hier om een grotere versie van deze figuur te bekijken.

Figuur 2. Primaire Bone Marrow Cultuur van de Cel voor differentiatie van osteoclasten en osteoblasten. (A) TRAP kleuring voor meerkernige osteoclasten na 7 dagen in osteoclastogenic media (4x). (B) Alkaline fosfatase (paarse kleur) voor osteoblasten en alizarinerood (rode kleur) vlek voor mineralisatie na 21 dagen in osteogene media. Afbeeldingen met dank aan Katherine Weilbaecher, Washington University School of Medicine, USA.iles / ftp_upload / 53936 / 53936fig2large.jpg "target =" _ blank "> Klik hier om een grotere versie van deze figuur te bekijken.

Discussion

We present a simple and efficient method for removal of mouse hind long bones and subsequent bone marrow isolation. This method maintains the high structural and cellular integrity of the bones and bone marrow and has low handling time, minimizing the likelihood of user-induced fracture or bone scoring that may influence downstream analyses. In addition, the centrifugation method for isolating bone marrow does not require cutting the bone to expose the bone marrow space or fluid to flush the bone marrow, reducing potential points of contamination. Moreover, the centrifuge technique is relatively high-throughput with lower hands-on time than other methods, thus reducing processing time.

High variation is inherent to in vivo mouse studies due to high mouse-to-mouse phenotypic variation. In order to maximize the research impact of expensive and labor-intensive mouse studies, it is critical to minimize technical experimental error9,10. Time from animal sacrifice to downstream analysis or tissue fixation introduces experimental variation that may overcome subtle changes and reduce large differences between groups. Therefore, rapid processing of samples is essential for accurate data analysis. The long bone dissection and bone marrow isolation techniques described here are optimized for rapid processing of animals and samples to reduce technical variation.

This protocol can be widely applied to many research fields, including investigation of the bone tissue itself or interrogation of the cells of the bone marrow. In addition, this straightforward approach to long bone dissection will enable researchers in related fields to directly interrogate bone contributions in order to expand our knowledge of bone marrow dysfunction in otherwise understudied pathologies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NCI grant nos. U54CA143803, CA163124, CA093900, and CA143055 to K.J.P. The authors thank the current and past members of the Weilbaecher lab, especially Katherine Weilbaecher, Michelle Hurchla, and Hongju Deng, and members of the Brady Urological Institute, especially members of the Pienta laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| pinboard | |||

| pins | |||

| 70% ethanol | |||

| dissection sissors | |||

| dissection forceps | |||

| Kimwipes | Kimberly-Clark | 34120 | |

| 16 guage needle | |||

| 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube | |||

| 0.5 ml microcentrifuge tube | |||

| microcentrifuge |

References

- McHayleh, W. M., Ellerman, J., Roodman, G. D. Ch. 80. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. , 379-381 (2008).

- Weilbaecher, K. N., Guise, T. A., McCauley, L. K. Cancer to bone: a fatal attraction. Nat Rev Cancer. 11 (6), 411-425 (2011).

- Pedersen, E. A., Shiozawa, Y., Pienta, K. J., Taichman, R. S. The prostate cancer bone marrow niche: more than just 'fertile soil. Asian J Androl. 14 (3), 423-427 (2012).

- Amend, S. R., et al. Thrombospondin-1 regulates bone homeostasis through effects on bone matrix integrity and nitric oxide signaling in osteoclasts. J Bone Miner Res. 30 (1), 106-115 (2015).

- Hurchla, M. A., et al. The epoxyketone-based proteasome inhibitors carfilzomib and orally bioavailable oprozomib have anti-resorptive and bone-anabolic activity in addition to anti-myeloma effects. Leukemia. 27 (2), 430-440 (2013).

- Rauch, D. A., et al. The ARF tumor suppressor regulates bone remodeling and osteosarcoma development in mice. PLoS One. 5 (12), e15755 (2010).

- Su, X., et al. The ADP receptor P2RY12 regulates osteoclast function and pathologic bone remodeling. J Clin Invest. 122 (10), 3579-3592 (2012).

- Dempster, D. W., et al. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 28 (1), 2-17 (2013).

- Begley, C. G., Ellis, L. M. Drug development: Raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature. 483 (7391), 531-533 (2012).

- Festing, M. F., Altman, D. G. Guidelines for the design and statistical analysis of experiments using laboratory animals. ILAR J. 43 (4), 244-258 (2002).

Explore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

ABOUT JoVE

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved