マウス後肢長骨解剖や骨髄の単離

In This Article

Summary

Here we present a protocol for the dissection of hind limb long bones (femurs and tibiae) from the laboratory mouse. We further describe a rapid technique for bone marrow isolation from these bones that utilizes centrifugation for removal of bone marrow from the bone marrow space.

Abstract

Investigation of the bone and the bone marrow is critical in many research fields including basic bone biology, immunology, hematology, cancer metastasis, biomechanics, and stem cell biology. Despite the importance of the bone in healthy and pathologic states, however, it is a largely under-researched organ due to lack of specialized knowledge of bone dissection and bone marrow isolation. Mice are a common model organism to study effects on bone and bone marrow, necessitating a standardized and efficient method for long bone dissection and bone marrow isolation for processing of large experimental cohorts. We describe a straightforward dissection procedure for the removal of the femur and tibia that is suitable for downstream applications, including but not limited to histomorphologic analysis and strength testing. In addition, we outline a rapid procedure for isolation of bone marrow from the long bones via centrifugation with limited handling time, ideal for cell sorting, primary cell culture, or DNA, RNA, and protein extraction. The protocol is streamlined for rapid processing of samples to limit experimental error, and is standardized to minimize user-to-user variability.

Introduction

The study of long bones and the cells of the bone marrow is central to a myriad of research disciplines, including, but not limited to, bone biology, cancer biology, immunology, hematology, and biomechanics. The bone is a highly dynamic organ that together with the cartilage forms the skeleton to provide mechanical support against loading and protection of the internal organs. In addition, the mineral components of bone are a storage sink for the critical signaling molecules calcium and phosphorus, as well as other factors1. Finally, bones house the bone marrow and, together with metabolically active bone forming osteoblasts and bone resorbing osteoclasts, provide the stem cell niche necessary for the maintenance of hematopoietic and lymphoid cell populations.

Bone and bone marrow are affected in many disorders, often leading to bone marrow dysfunction, severe bone pain, and pathologic fracture. Bone is a common site of metastasis in many solid tumors, most notably breast cancer and prostate cancer, where tumor cells directly engage the bone marrow niche to initiate the vicious cycle of bone metastasis and displace hematopoietic stem cells2,3. Hematopoietic malignancies including myeloma and leukemia are characterized by bone marrow dysfunction as well as deregulation of healthy bone remodeling1. Other non-malignant skeletal disorders are also active areas of research, such as osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, scoliosis, and rickets. Even in an otherwise healthy individual, biomechanical failure in a bone leads to a painful fracture. All of these disorders represent active areas of research with the goal of identifying new preventative measures and treatment regimens to reduce morbidity and mortality.

To research the plethora of roles of the bone and the bone marrow, both under physiologic and pathologic conditions, it is critical for researchers to have a simple and efficient standardized method for dissection of the mouse long bones for rapid processing of large in vivo experiments. The dissection protocol outlined here is suitable for all long bone analyses including ex vivo imaging, histology, histomorphometry, and strength testing, among others. Similarly, a standardized bone marrow isolation method with high bone marrow cell recovery and low inter-user variability is important for experimental analysis such as fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) or quantitative PCR (qPCR) as well as downstream applications such as primary cell culture of bone marrow cells.

Protocol

すべての動物の作業は、国立衛生研究所の実験動物の管理と使用のためのガイドで概説勧告に従って施設内動物管理使用委員会によって承認されました。

1.後肢長骨の解剖

- 施設の指針に従ってマウスを安楽死させます。

- 仰臥位でマウスを合わせ、足関節以下のマウスの足のパッドを介してすべての4脚を固定することによって貼り付けます。

- 徹底的に足をdousing、70%エタノールでマウスをスプレーします。

- ちょうど腰の上に、下腹部正中線の右側に小さな切開を行います。

- 脚のダウンと足首関節過去の切開を拡張します。

- 皮膚を引いて、ボードから45度の角度でピンを配置し、大腿骨の前方側を露出させ、脚部からピンに大腿骨の近位端に固定された大腿四頭筋を切りました。

- 宣伝ちらしと大腿骨の後部側面にはさみのeは、離れて膝関節からのハムストリングスにカット。

- ボードから45度の角度でピンを配置し、大腿骨の後側を露出させ、脚部からピンに大腿骨の近位端に固定され、皮膚とハムストリングの筋肉を引き戻します。

- ピンセットで、ちょうど膝関節の上に、大腿骨の遠位端部を保持します。大腿骨自体にカットしないように注意して、股関節に向かって大腿骨シャフトの両側にハサミの刃を案内します。

- 少し開いハサミで示される大腿骨頭を、到達した後、大腿骨頭下の骨をスナップしないように注意して、大腿骨を脱臼する大腿骨頭の真上に移動ハサミのトップブレードではさみをねじります。

- ピンセットで大腿骨シャフトの上部をつかみ、寛骨臼からそれを解放するために離れて大腿骨頭から軟部組織を切断します。

- 含め、全体の足の骨を引っ張りますアップや身体から離し大腿、膝、および脛骨、慎重に皮膚に足を接続する結合組織と筋肉を切り取ります。

- 足首関節を使い過ぎると再び脛骨を脱臼するねじれ運動にはさみを使用しています。

- 、脛骨の遠位端を把握腱を切断しないように注意しながら、アップと離れて本体とピンボードから脛骨を引き出します。

- 膝のマウスに、長骨を取り付ける任意の残りの結合組織をカット。

- 任意の追加の筋肉や大腿骨と脛骨に付着した結合組織を削除します。

- (組織学、組織形態計測、生体力学的試験、 など 。)、無傷のままに骨を必要とするアプリケーションの場合、(4-7のように)標準的な社内のプロトコルを進めます。骨髄を単離するために、セクション2に進んでください。

骨髄の単離2.長骨の準備

- 鉗子の使用、膝蓋骨は反対側で大腿骨を把握ndは近位端部(大腿骨頭)ダウン。

- 膝関節を使い過ぎると脛骨と大腿骨を脱臼するねじれ運動にはさみを使用しています。

- 一緒に大腿骨と脛骨を保持する任意の結合組織をカット。

- 鉗子を使用して、反対の前方側と近位端(大腿骨頭端)ダウンして大腿骨を把握します。

- 顆の大腿骨軸をはさみを導きます。

- ゆっくり顆、膝蓋骨、そして骨幹を公開する骨端を除去するために、前後にはさみを回転させます。

- 任意の追加の筋肉や鉗子、はさみ、およびキムワイプを使用して大腿骨に付着し結合組織を削除します。

- 鉗子を使用して、反対の前方側と先端(足首端)ダウンと脛骨を把握します。

- 脛骨骨端が無傷である場合は、顆に脛骨の軸をはさみを導きます。

- ゆっくりmetaphを露出するように顆と骨端を除去するために、前後にはさみを回転させますysis。

- 追加の筋肉または鉗子、はさみ、およびキムワイプを使用して脛骨に付着した結合組織を取り除きます。

3.骨髄単離

- 0.5ミリリットルマイクロチューブの底から18 G針を押してください。

- チューブに長骨(2大腿骨の最大値と2脛骨)を配置し、膝エンドダウンダウン終了し、ふたを閉めます。

- ネスト1.5ミリリットルマイクロ遠心チューブ中の0.5 mlのマイクロ遠心チューブ。

- 15秒間微量で≥10,000×gで、ネストされたチューブを遠心。

- 骨髄は目視検査により骨のスピンアウトされていることを確認します。骨は白表示され、より大きなチューブに大きな視覚的にペレットがあるはずです。

- 骨0.5 mlマイクロチューブを捨てます。

- 、適切な溶液中での骨髄( 例えば 、PBS、培地、FACSバッファー)を中断し、実験プロトコル(DNA、RNA、またはタンパク質の分離を進めますFACS分析、または初代細胞培養)。

Representative Results

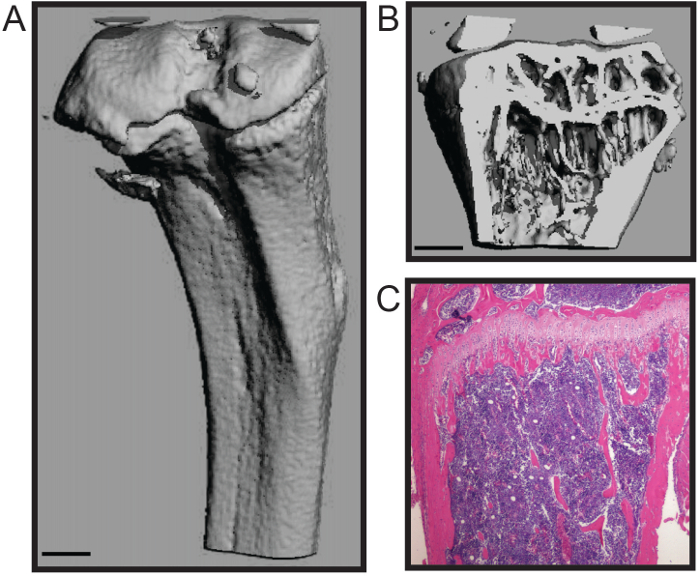

ここで説明するプロトコルは、骨組織への損傷を最小限に抑えて、マウスの大腿骨と脛骨の迅速な解剖のために最適化されています。 、および組織学( 図1C)4,7 -この技術はバイオメカニクス研究、組織形態計測(B図1A)を含む下流の分析の数、に適しています。代表histomophometric micoCT 3D再構成( 図1A - B)は、海綿骨と皮質シェルの両方が小柱数、厚さ、及び間隔を含む骨組織形態計測のための標準化された構造パラメータの正確な定量が可能になり、その維持されていることを示しています。骨量;その他の措置8の中で、皮質の厚さ、。代表的な組織学的セクションでは、H&E染色したホルマリン固定し、脱灰脛骨( 図1C)を示しています。画像は石灰化bの両方の完全性を実証します1および組織学的分析のための細胞の骨髄。

骨髄の単離手順は、骨髄空間の無菌性を維持し、汚染を低減するために低い処理を有し、したがって、骨髄収率の損失を低減すること、長骨の切断を必要としません。この骨髄5及びPCR分析、フローサイトメトリーを含む多くの下 流の用途に適しています。 4,6 -また、この手順は、破骨細胞および骨芽細胞(B図2A)を含む骨髄細胞の初代細胞培養物のための骨髄を単離することができます。

図1.組織形態学的およびマウスの長骨の組織学的分析。(A)は、外側皮質殻を示すマウスの脛骨の3次元マイクロCT再構成および(B trong>)骨梁(スケールバー= 0.5ミリメートル)。 (C)脱灰と切片脛骨(4倍)の組織学的H&E染色。画像キャサリンWeilbaecher、医学、アメリカのワシントン大学の礼儀。 この図の拡大版を表示するには、こちらをクリックしてください。

破骨細胞と骨芽細胞の分化のための図2.初代骨髄細胞培養。破骨細胞形成メディア(4倍速)で7日後の多核破骨細胞のための(A)TRAP染色。 (B)骨芽細胞および骨形成培地で21日後の石灰化のためのアリザリンレッド(赤色)染色のためのアルカリホスファターゼ(紫色)。キャサリンWeilbaecher、医学、アメリカのワシントン大学の画像が礼儀。ジル/ ftp_upload / 53936 / 53936fig2large.jpg "ターゲット=" _空白 ">この図の拡大版をご覧になるにはこちらをクリックしてください。

Discussion

We present a simple and efficient method for removal of mouse hind long bones and subsequent bone marrow isolation. This method maintains the high structural and cellular integrity of the bones and bone marrow and has low handling time, minimizing the likelihood of user-induced fracture or bone scoring that may influence downstream analyses. In addition, the centrifugation method for isolating bone marrow does not require cutting the bone to expose the bone marrow space or fluid to flush the bone marrow, reducing potential points of contamination. Moreover, the centrifuge technique is relatively high-throughput with lower hands-on time than other methods, thus reducing processing time.

High variation is inherent to in vivo mouse studies due to high mouse-to-mouse phenotypic variation. In order to maximize the research impact of expensive and labor-intensive mouse studies, it is critical to minimize technical experimental error9,10. Time from animal sacrifice to downstream analysis or tissue fixation introduces experimental variation that may overcome subtle changes and reduce large differences between groups. Therefore, rapid processing of samples is essential for accurate data analysis. The long bone dissection and bone marrow isolation techniques described here are optimized for rapid processing of animals and samples to reduce technical variation.

This protocol can be widely applied to many research fields, including investigation of the bone tissue itself or interrogation of the cells of the bone marrow. In addition, this straightforward approach to long bone dissection will enable researchers in related fields to directly interrogate bone contributions in order to expand our knowledge of bone marrow dysfunction in otherwise understudied pathologies.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by NCI grant nos. U54CA143803, CA163124, CA093900, and CA143055 to K.J.P. The authors thank the current and past members of the Weilbaecher lab, especially Katherine Weilbaecher, Michelle Hurchla, and Hongju Deng, and members of the Brady Urological Institute, especially members of the Pienta laboratory for critical reading of the manuscript.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| pinboard | |||

| pins | |||

| 70% ethanol | |||

| dissection sissors | |||

| dissection forceps | |||

| Kimwipes | Kimberly-Clark | 34120 | |

| 16 guage needle | |||

| 1.5 ml microcentrifuge tube | |||

| 0.5 ml microcentrifuge tube | |||

| microcentrifuge |

References

- McHayleh, W. M., Ellerman, J., Roodman, G. D. Ch. 80. Primer on the Metabolic Bone Diseases and Disorders of Mineral Metabolism. , 379-381 (2008).

- Weilbaecher, K. N., Guise, T. A., McCauley, L. K. Cancer to bone: a fatal attraction. Nat Rev Cancer. 11 (6), 411-425 (2011).

- Pedersen, E. A., Shiozawa, Y., Pienta, K. J., Taichman, R. S. The prostate cancer bone marrow niche: more than just 'fertile soil. Asian J Androl. 14 (3), 423-427 (2012).

- Amend, S. R., et al. Thrombospondin-1 regulates bone homeostasis through effects on bone matrix integrity and nitric oxide signaling in osteoclasts. J Bone Miner Res. 30 (1), 106-115 (2015).

- Hurchla, M. A., et al. The epoxyketone-based proteasome inhibitors carfilzomib and orally bioavailable oprozomib have anti-resorptive and bone-anabolic activity in addition to anti-myeloma effects. Leukemia. 27 (2), 430-440 (2013).

- Rauch, D. A., et al. The ARF tumor suppressor regulates bone remodeling and osteosarcoma development in mice. PLoS One. 5 (12), e15755 (2010).

- Su, X., et al. The ADP receptor P2RY12 regulates osteoclast function and pathologic bone remodeling. J Clin Invest. 122 (10), 3579-3592 (2012).

- Dempster, D. W., et al. Standardized nomenclature, symbols, and units for bone histomorphometry: a 2012 update of the report of the ASBMR Histomorphometry Nomenclature Committee. J Bone Miner Res. 28 (1), 2-17 (2013).

- Begley, C. G., Ellis, L. M. Drug development: Raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature. 483 (7391), 531-533 (2012).

- Festing, M. F., Altman, D. G. Guidelines for the design and statistical analysis of experiments using laboratory animals. ILAR J. 43 (4), 244-258 (2002).

Explore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

ABOUT JoVE

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved