A subscription to JoVE is required to view this content. Sign in or start your free trial.

Method Article

Assessing the Influence of Personality on Sensitivity to Magnetic Fields in Zebrafish

In This Article

Summary

We describe a behavioral protocol designed to assess how zebrafish’s personalities influence their response to water currents and weak magnetic fields. Fishes with the same personalities are separated based on their explorative behavior. Then, their rheotactic orientation behavior in a swimming tunnel with a low flow rate and under different magnetic conditions is observed.

Abstract

To orient themselves in their environment, animals integrate a wide array of external cues, which interact with several internal factors, such as personality. Here, we describe a behavioral protocol designed for the study of the influence of zebrafish personality on their orientation response to multiple external environmental cues, specifically water currents and magnetic fields. This protocol aims to understand whether proactive or reactive zebrafish display different rheotactic thresholds (i.e., the flow speed at which the fish start swimming upstream) when the surrounding magnetic field changes its direction. To identify zebrafish with the same personality, fish are introduced in the dark half of a tank connected with a narrow opening to a bright half. Only proactive fish explore the novel, bright environment. Reactive fish do not exit the dark half of the tank. A swimming tunnel with low flow rates is used to determine the rheotactic threshold. We describe two setups to control the magnetic field in the tunnel, in the range of the earth’s magnetic field intensity: one that controls the magnetic field along the flow direction (one dimension) and one that allows a three-axial control of the magnetic field. Fish are filmed while experiencing a stepwise increase of the flow speed in the tunnel under different magnetic fields. Data on the orientation behavior are collected through a video-tracking procedure and applied to a logistic model to allow the determination of the rheotactic threshold. We report representative results collected from shoaling zebrafish. Specifically, these demonstrate that only reactive, prudent fish show variations of the rheotactic threshold when the magnetic field varies in its direction, while proactive fish do not respond to magnetic field changes. This methodology can be applied to the study of magnetic sensitivity and rheotactic behavior of many aquatic species, both displaying solitary or shoaling swimming strategies.

Introduction

In the present study, we describe a lab-based behavioral protocol which has the scope of investigating the role of fish personality on the orientation response of shoaling fish to external orientation cues, such as water currents and magnetic fields.

The orienting decisions of animals result from weighing various sensory information. The decision process is influenced by the ability of the animal to navigate (e.g., the capacity to select and keep a direction), its internal state (e.g., feeding or reproductive needs), its ability to move (e.g., locomotion biomechanics), and several additional external factors (e.g., time of day, interaction with conspecifics)1.

The role of the internal state or animal personality in the orientation behavior is often poorly understood or not explored2. Additional challenges arise in the study of the orientation of social aquatic species, which often perform coordinated and polarized group movement behavior3.

Water currents play a key role in the orientation process of fish. Fish orient to water currents through an unconditioned response called rheotaxis4, which can be positive (i.e., upstream oriented) or negative (i.e. downstream oriented) and is used for several activities, ranging from foraging to the minimization of energetic expenditure5,6. Moreover, a growing body of literature reports that many fish species use the geomagnetic field for orientation and navigation7,8,9.

The study of rheotaxis and swimming performance in the fish is usually conducted in flow chambers (flume), where fish are exposed to the stepwise increase of the flow speed, from low to high speeds, often until exhaustion (called critical speed)10,11. On the other hand, previous studies investigated the role of the magnetic field in the orientation through the observation of the swimming behavior of the animals in arenas with still water12,13. Here, we describe a laboratory technique that allows researchers to study the behavior of fish while manipulating both the water currents and the magnetic field. This method was utilized for the first time on shoaling zebrafish (Danio rerio) in our previous study, leading to the conclusion that the manipulation of the surrounding magnetic field determines the rheotactic threshold (i.e., the minimal water speed at which shoaling fish orient upstream)14. This method is based on the use of a flume chamber with slow flows combined with a setup designed to control the magnetic field in the flume, within the range of the earth’s magnetic field intensity.

The swimming tunnel utilized to observe the behavior of zebrafish is outlined in Figure 1. The tunnel (made of a nonreflecting acrylic cylinder with a 7 cm diameter and 15 cm in length) is connected to a setup for the control of the flow rate14. With this setup, the range of flow rates in the tunnel varies between 0 and 9 cm/s.

To manipulate the magnetic field in the swimming tunnel, we use two methodological approaches: the first is one-dimensional and the second is three-dimensional. For any application, these methods manipulate the geomagnetic field to obtain specific magnetic conditions in a defined volume of water—thus, all the values of magnetic field intensity reported in this study include the geomagnetic field.

Concerning the one-dimensional approach15, the magnetic field is manipulated along the water flow direction (defined as the x-axis) using a solenoid wrapped around the swimming tunnel. This is connected to a power unit, and it generates uniform static magnetic fields (Figure 2A). Similarly, in the case of the three-dimensional approach, the geomagnetic field in the volume containing the swimming tunnel is modified using coils of electric wires. However, to control the magnetic field in three dimensions, the coils have the design of three orthogonal Helmholtz pairs (Figure 2B). Each Helmholtz pair is composed of two circular coils oriented along the three orthogonal space directions (x, y, and z) and equipped with a three-axial magnetometer working in closed-loop conditions. The magnetometer works with field intensities comparable with the earth’s natural field, and it is located close to the geometrical center of the coils set (where the swimming tunnel is located).

We implement the techniques described above to test the hypothesis that the personality traits of the fish composing a shoal influence the way they respond to magnetic fields16. We test the hypothesis that individuals with proactive and reactive personality17,18 respond differently when exposed to water flows and magnetic fields. To test this, we first sort zebrafish using an established methodology to assign and group individuals that are proactive or reactive17,19,20,21. Then, we evaluate the rheotactic behavior of zebrafish swimming in shoals composed of only reactive individuals or composed of only proactive individuals in the magnetic flume tank, which we present as sample data.

The sorting method is based on the different tendency of the proactive and reactive individuals to explore novel environments21. Specifically, we use a tank divided into a bright and a dark side17,19,20,21 (Figure 3). Animals are acclimated to the dark side. When access to the bright side is open, proactive individuals tend to quickly exit the dark half of the tank to explore the new environment, while the reactive fish do not leave the dark tank.

Protocol

The following protocol has been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Naples Federico II, Naples, Italy (2015).

1. Animal Maintenance

- Use tanks of at least 200 L to host a shoal of at least 50 individuals of both sexes in each tank.

NOTE: The density of the fish in the tank has to be one animal per 2 L or lower. Under these conditions, zebrafish will display normal shoaling behavior. - Set the maintenance conditions as follow: temperature at 27–28 °C; conductivity at <500 μS; pH 6.5–7.5; NO3 at <0.25 mg/L; and a light:dark photoperiod at 10 h:14 h.

NOTE: Identical holding conditions must be used for both the mixed population and the separated proactive and reactive populations.

2. Personality Selection in Zebrafish

- Prepare and place the personality selection tank in a quiet room (Figure 3) with the same water as used in the maintenance tanks.

- Place a video camera above or at the side of the tank. Connect the camera to a computer with a monitor located in an area where there is no visual contact with the tank.

- Select nine fish at random from the maintenance tank and transfer them to the dark side of the personality selection tank, using a knotless net.

NOTE: Try to limit the interactions with the tanks and fish to the least amount of time possible. Avoid noise and fast movements. If necessary, transfer the animals in a small volume transporting tank (about 2 L) with water from the holding tank. To avoid air exposure of animals, use a 250 ml beaker and gently induce the animal to enter the beaker. Try to minimize the capture time, avoid collecting multiple fish as it might cause physical damage to the animals and do not hold fish for more than a few seconds in the net as these factors can increase stress. Fish must be fed ad libitum prior to the transfer to the experimental tank. This limits the possibility that different tendencies of food-seeking behavior would affect the behavior of the individuals during the following experiment22. Conduct replicate experiments at the same time of the day. This minimizes variability in the behavior of the experimental groups caused by possible circadian rhythms23. - After 1 h of acclimatization, open the sliding door.

NOTE: Individuals who exit from the hole, exploring the bright side of the tank within 10 min, are considered proactive21. - After 10 min, gently remove the proactive individuals from the tank and transfer them to the proactive maintenance tank.

- After 15 min, collect the fish that remain in the dark box, which are considered reactive21, and transfer them to the reactive maintenance tank.

NOTE: Discard fish that move to the bright side of the tank after 10 min21. Perform the personality test with nine fish at a time until the desired number of proactive and reactive fish necessary for the tests described in section 5 are collected. Consistency of the proactive and reactive personality can be checked regularly using the same approach.

3. Set up of the Magnetic Field with the One-dimensional Magnetic Field Manipulation27

- Switch on the Power unit (Figure 2A).

- Place the coiled tunnel in the location where the rheotactic protocol will be performed (section 5) but keep it disconnected from the swimming apparatus (Figure 2A). Place a magnetic probe connected with a Gauss/Teslameter inside the tunnel and verify which voltage is necessary to obtain the chosen magnetic field value along the major axis of the tunnel.

NOTE: Because of the magnetic properties of a solenoid, the field is reasonably uniform inside the tunnel; this can be checked by slowly moving the probe both horizontally and vertically. - Disconnect the probe and connect the flow tunnel to the swimming apparatus.

- Start with the rheotactic protocol (section 5).

4. Set Up of the Magnetic Field with the Three-dimensional Magnetic Field Manipulation27

- Switch on the CPU, DAC, and coil drivers (Figure 2B).

- Set the chosen magnetic field on each one of the three axes (x, y, and z).

- Place the tunnel in the center of the Helmholtz pairs set.

- Start with the rheotactic protocol (section 5).

5. Test of the Zebrafish Rheotaxis in the Flow Chamber

- Transfer one to five fish to the flow tunnel using a 2 L tank with the sides and the bottom obscured.

- Turn on the pump and set the flow rate in the tunnel to 1.7 cm/s.

NOTE: This slow-moving water will keep the water in the tunnel oxygenated and it will facilitate animal recovery. - Let the animals acclimate to the swimming tunnel for 1 h.

- Start the video recording of the behavior of the fish in the tunnel.

NOTE: We used a camera (e.g., Yi 4K Action) with remote control (e.g., Bluetooth) and saved the video as .mpg (30 frames/s). - Start the stepwise increase of the flow rate according to the chosen experimental protocol (1.3 cm/s in this study; Figure 4).

NOTE: For this protocol, we used low flow rates which, for zebrafish, range from 0 to 2.8 BL (body lengths)/s. These flow speeds are in the lower range of flow rates that induce continuous oriented swimming in zebrafish (3%–15% of critical swimming speed [Ucrit])24. The use of low flow rates (following Brett’s protocol25) is linked to the specific behavioral characteristics of this species in the presence of water currents. Zebrafish tend to swim along the major axis of the chamber, turning frequently, even in the presence of water flow, and tend to swim both upstream and downstream24,26. This behavior is affected by the water flow rate, disappearing at relatively high speeds (>8 BL/s)26, when the animals continuously swim facing upstream (full positive rheotactic response). Vertical and transversal displacements are very rare. - Perform morphometry of the animals (sex and total length [TL], fork length [FL], or BL) on pictures of fish in a morphometric chamber.

- Select the appropriate picture.

- Open the picture in ImageJ.

- Take note of the sex of the animal (male zebrafish are slender and tend to be yellowish, while females are more rounded and tend to have blue and white colorings).

- Click Analyze > Set Scale and set the scale of the image in centimeters, using the whole horizontal length of the tunnel as reference.

- Click Analyze > Measure and record the linear length of the animal.

- Calculate its body weight (BW).

NOTE: BW is calculated from sex-FL-BW relationships previously built in the lab or from metadata. The whole procedure avoids manipulation stress on the animals.

6. Video Tracking

- Open the video file with Tracker 4.84 Video Analysis and Modeling Tool.

NOTE: If necessary, correct any video distortion using perspective and radial distortion filters. - Click on Coordinate system in the upper menu and set the length units to centimeters and the time units to seconds.

- Click on File > Import > Video and open one of the videos in Tracker 4.84.

- Click on “Coordinate axes” and set the reference system to track the position of the fish over time, with the x axis along the tunnel. Set the origin at the low corner of the downstream ending wall (at the water outlet).

- Click on Track > New > Point of mass and start tracking one fish at a time. Track the last 5 min of each step that the fish spent at each flow rate.

- Advance the video manually at five-frame intervals (0.5 s) and mark the time and position of the animal at each upstream-downstream turn (UDt; red dots in Figure 5) and at each downstream-upstream turn (DUt; blue dots in Figure 5).

NOTE: Use the fish eye position as a reference for the fish’s position. Track the animal’s position using a Point mass. Exclude from the tracking any period of non-oriented swimming (i.e., maneuvering time). - At the end of each tracking session, select the x-values and time values from the table at the bottom-right corner of the software window. Right-click on the data and click Copy data > Full precision.

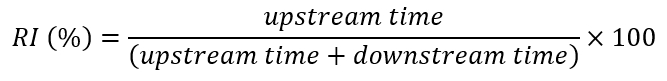

- Save the time values and x-values of all turning positions on a template spreadsheet file to calculate the total upstream time (sum of all the intervals between UDts and DUts) and the total downstream time (sum of the intervals between DUts and UDt), as well as the values of the rheotactic index in percentages (RI%) for each flow step (see Figure 5).

NOTE: The rheotactic behavior is quantified by the proportion of the total oriented time that the fish spend facing upstream (swimming or rarely freezing [i.e., they stay still at the bottom of the tunnel]27). This proportion is defined as the RI% (Figure 5).

Results

As sample data we present results obtained controlling the magnetic field along the water flow direction on proactive and reactive shoaling zebrafish16 using the setup shown in Figure 2A (see section 3 of the protocol). These results show how the described protocol can highlight differences in responses to the magnetic field in fish with different personalities. The overall concept of these trials relies on the finding that the directi...

Discussion

The protocol described in this study allows scientists to quantify complex orientation responses of aquatic species resulting from the integration between two external cues (water current and geomagnetic field) and one internal factor of the animal, such as personality. The overall concept is to create an experimental design that allows scientists to separate individuals of different personality and investigate their orientation behavior while controlling separately or simultaneously the external environmental cues.

...Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The study was supported by the Basic Research Founding of the Physics Department and the Biology Department of the Naples University Federico II. The authors thank Dr. Claudia Angelini (Institute of Applied Calculus, Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche [CNR], Italy) for the statistical support. The authors thank Martina Scanu and Silvia Frassinet for their technical help with collecting the data, and the departmental technicians F. Cassese, G. Passeggio, and R. Rocco for their skillful assistance in the design and realization of the experimental setup. We thank Laura Gentile for helping conducting the experiment during the video shooting. We thank Diana Rose Udel from the University of Miami for shooting the interview statements of Alessandro Cresci.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 9500 G meter | FWBell | N/A | Gaussmeter, DC-10 kHz; probe resolution: 0.01 μT |

| AD5755-1 | Analog Devices | EVAL-AD5755SDZ | Quad Channel, 16-bit, Digital to Analog Converter |

| ALR3003D | ELC | 3760244880031 | DC Double Regulated power supply |

| BeagleBone Black | Beagleboard.org | N/A | Single Board Computer |

| Coil driver | Home made | N/A | Amplifier based on commercial OP (OPA544 by TI) |

| Helmholtz pairs | Home made | N/A | Coils made with standard AWG-14 wire |

| HMC588L | Honeywell | 900405 Rev E | Digital three-axis magnetometer |

| MO99-2506 | FWBell | 129966 | Single axis magnetic probe |

| Swimming apparatus | M2M Engineering Custom Scientific Equipment | N/A | Swimming apparatus composed by peristaltic pump and SMC Flow switch flowmeter with digital feedback |

| TECO 278 | TECO | N/A | Thermo-cryostat |

References

- Nathan, R., et al. A movement ecology paradigm for unifying organismal movement research. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (49), 19052-19059 (2008).

- Holyoak, M., Casagrandi, R., Nathan, R., Revilla, E., Spiegel, O. Trends and missing parts in the study of movement ecology. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 105 (49), 19060-19065 (2008).

- Miller, N., Gerlai, R. From Schooling to Shoaling: Patterns of Collective Motion in Zebrafish (Danio rerio). PLoS ONE. 7 (11), 8-13 (2012).

- Chapman, J. W., et al. Animal orientation strategies for movement in flows. Current Biology. 21 (20), R861-R870 (2011).

- Montgomery, J. C., Baker, C. F., Carton, A. G. The lateral line can mediate rheotaxis in fish. Nature. 389 (6654), 960-963 (1997).

- Baker, C. F., Montgomery, J. C. The sensory basis of rheotaxis in the blind Mexican cave fish, Astyanax fasciatus. Journal of Comparative Physiology A: Sensory, Neural, and Behavioral Physiology. 184 (5), 519-527 (1999).

- Putman, N. F., et al. An Inherited Magnetic Map Guides Ocean Navigation in Juvenile Pacific Salmon. Current Biology. 24 (4), 446-450 (2014).

- Cresci, A., et al. Glass eels (Anguilla anguilla) have a magnetic compass linked to the tidal cycle. Science Advances. 3 (6), 1-9 (2017).

- Newton, K. C., Kajiura, S. M. Magnetic field discrimination, learning, and memory in the yellow stingray (Urobatis jamaicensis). Animal Cognition. 20 (4), 603-614 (2017).

- Langdon, S. A., Collins, A. L. Quantification of the maximal swimming performance of Australasian glass eels, Anguilla australis and Anguilla reinhardtii, using a hydraulic flume swimming chamber. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 34 (4), 629-636 (2000).

- Faillettaz, R., Durand, E., Paris, C. B., Koubbi, P., Irisson, J. O. Swimming speeds of Mediterranean settlement-stage fish larvae nuance Hjort’s aberrant drift hypothesis. Limnology and Oceanography. 63 (2), 509-523 (2018).

- Takebe, A., et al. Zebrafish respond to the geomagnetic field by bimodal and group-dependent orientation. Scientific Reports. 2, 727 (2012).

- Osipova, E. A., Pavlova, V. V., Nepomnyashchikh, V. A., Krylov, V. V. Influence of magnetic field on zebrafish activity and orientation in a plus maze. Behavioural Processes. 122, 80-86 (2016).

- Cresci, A., De Rosa, R., Putman, N. F., Agnisola, C. Earth-strength magnetic field affects the rheotactic threshold of zebrafish swimming in shoals. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology - Part A: Molecular and Integrative Physiology. 204, 169-176 (2017).

- Tesch, F. W. Influence of geomagnetism and salinity on the directional choice of eels. Helgoländer Wissenschaftliche Meeresuntersuchungen. 26 (3-4), 382-395 (1974).

- Cresci, A., et al. Zebrafish “personality” influences sensitivity to magnetic fields. Acta Ethologica. , 1-7 (2018).

- Benus, R. F., Bohus, B., Koolhaas, J. M., Van Oortmerssen, G. A. Heritable variation for aggression as a reflection of individual coping strategies. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 47 (10), 1008-1019 (1991).

- Dahlbom, S. J., Backstrom, T., Lundstedt-Enkel, K., Winberg, S. Aggression and monoamines: Effects of sex and social rank in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Behavioural Brain Research. 228 (2), 333-338 (2012).

- Koolhaas, J. M. Coping style and immunity in animals: Making sense of individual variation. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 22 (5), 662-667 (2008).

- Dahlbom, S. J., Lagman, D., Lundstedt-Enkel, K., Sundström, L. F., Winberg, S. Boldness predicts social status in zebrafish (Danio rerio). PLoS ONE. 6 (8), 2-8 (2011).

- Rey, S., Boltana, S., Vargas, R., Roher, N., Mackenzie, S. Combining animal personalities with transcriptomics resolves individual variation within a wild-type zebrafish population and identifies underpinning molecular differences in brain function. Molecular Ecology. 22 (24), 6100-6115 (2013).

- Toms, C. N., Echevarria, D. J., Jouandot, D. J. A Methodological Review of Personality-related Studies in Fish: Focus on the Shy-Bold Axis of Behavior. International Journal of Comparative Psychology. 23, 1-25 (2010).

- Boujard, T., Leatherland, J. F. Circadian rhythms and feeding time in fishes. Environmental Biology of Fishes. 35 (2), 109-131 (1992).

- Plaut, I. Effects of fin size on swimming performance, swimming behaviour and routine activity of zebrafish Danio rerio. Journal of Experimental Biology. 203 (4), 813-820 (2000).

- Tierney, P., Farmer, S. M. Creative Self-Efficacy Development and Creative Performance Over Time. Journal of Applied Psychology. 96 (2), 277-293 (2011).

- Plaut, I., Gordon, M. S. swimming metabolism of wild-type and cloned zebrafish brachydanio rerio. Journal of Experimental Biology. 194 (1), (1994).

- Kalueff, A. V., et al. Towards a comprehensive catalog of zebrafish behavior 1.0 and beyond. Zebrafish. 10 (1), 70-86 (2013).

- Tudorache, C., Schaaf, M. J. M., Slabbekoorn, H. Covariation between behaviour and physiology indicators of coping style in zebrafish (Danio rerio). Journal of Endocrinology. 219 (3), 251-258 (2013).

- Uliano, E., et al. Effects of acute changes in salinity and temperature on routine metabolism and nitrogen excretion in gambusia (Gambusia affinis) and zebrafish (Danio rerio). Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 157 (3), 283-290 (2010).

- Palstra, A. P., et al. Establishing zebrafish as a novel exercise model: Swimming economy, swimming-enhanced growth and muscle growth marker gene expression. PLoS ONE. 5 (12), (2010).

- Bak-Coleman, J., Court, A., Paley, D. A., Coombs, S. The spatiotemporal dynamics of rheotactic behavior depends on flow speed and available sensory information. The Journal of Experimental Biology. 216, 4011-4024 (2013).

- Brett, J. R. The Respiratory Metabolism and Swimming Performance of Young Sockeye Salmon. Journal of the Fisheries Research Board of Canada. 21 (5), 1183-1226 (1964).

- Quintella, B. R., Mateus, C. S., Costa, J. L., Domingos, I., Almeida, P. R. Critical swimming speed of yellow- and silver-phase European eel (Anguilla anguilla, L.). Journal of Applied Ichthyology. 26 (3), 432-435 (2010).

- Spence, R., Gerlach, G., Lawrence, C., Smith, C. The behaviour and ecology of the zebrafish, Danio rerio. Biological Reviews. 83 (1), 13-34 (2008).

- Engeszer, R. E., Patterson, L. B., Rao, A. A., Parichy, D. M. Zebrafish in the Wild: A Review of Natural History and New Notes from the Field. Zebrafish. 4 (1), (2007).

- Gardiner, J. M., Atema, J. Sharks need the lateral line to locate odor sources: rheotaxis and eddy chemotaxis. Journal of Experimental Biology. 210 (11), 1925-1934 (2007).

- Thorpe, J. E., Ross, L. G., Struthers, G., Watts, W. Tracking Atlantic salmon smolts, Salmo salar L., through Loch Voil, Scotland. Journal of Fish Biology. 19 (5), 519-537 (1981).

- Bottesch, M., et al. A magnetic compass that might help coral reef fish larvae return to their natal reef. Current Biology. 26 (24), R1266-R1267 (2016).

- Boles, L. C., Lohmann, K. J. True navigation and magnetic maps in spiny lobsters. Nature. 421 (6918), 60-63 (2003).

- Dingemanse, N. J., Kazem, A. J. N., Réale, D., Wright, J. Behavioural reaction norms: animal personality meets individual plasticity. Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 25 (2), 81-89 (2010).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved