High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

Source: Dr. Paul Bower - Purdue University

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) is an important analytical method commonly used to separate and quantify components of liquid samples. In this technique, a solution (first phase) is pumped through a column that contains a packing of small porous particles with a second phase bound to the surface. The different solubilities of the sample components in the two phases cause the components to move through the column with different average velocities, thus creating a separation of these components. The pumped solution is called the mobile phase, while the phase in the column is called the stationary phase.

There are several modes of liquid chromatography, depending upon the type of stationary and/or mobile phase employed. This experiment uses reversed-phase chromatography, where the stationary phase is non-polar, and the mobile phase is polar. The stationary phase to be employed is C18 hydrocarbon groups bonded to 3-µm silica particles, while the mobile phase is an aqueous buffer with a polar organic modifier (acetonitrile) added to vary its eluting strength. In this form, the silica can be used for samples that are water-soluble, providing a broad range of applications. In this experiment, the mixtures of three components frequently found in diet soft drinks (namely caffeine, benzoate, and aspartame) are separated. Seven prepared solutions containing known amounts of the three species are used, and their chromatograms are then recorded.

During an HPLC experiment, a high-pressure pump takes the mobile phase from a reservoir through an injector. It then travels through a reverse-phase C18-packed column for component separation. Finally, the mobile phase moves into a detector cell, where the absorbance is measured at 220 nm, and ends in a waste bottle. The amount of time it takes for a component to travel from the injector port to the detector is called the retention time.

A liquid chromatograph is used in this experiment, where separation is performed on a reverse-phase column. The column dimensions are 3 mm (i.d.) x 100 mm, and the silica packing (3-µm particle size) is functionalized with C18 octadecylsilane (ODS). A Rheodyne 6-port rotary injection valve is used to initially store the sample in a small loop and introduces the sample to the mobile phase upon rotation of the valve.

Detection is by absorption spectroscopy at a wavelength of 220 nm. This experiment can be run at 254 nm, if a detector is not variable. Data from the detector has an analog voltage output, which is measured using a digital multimeter (DMM), and read by a computer loaded with a data acquisition program. The resulting chromatogram has a peak for every component in the sample. For this experiment, all three components elute within 5 min.

This experiment uses a single mobile phase and pump, which is called an isocratic mobile phase. For samples that are difficult to separate, a gradient mobile phase can be used. This is when the initial mobile phase is primarily an aqueous one, and over time, a second organic mobile phase is gradually added to the overall mobile phase. This method raises the polarity of this phase over time, which lowers the retention times of the components and works similarly to a temperature gradient on a gas chromatograph. There are some instances where the column is heated (usually to 40 °C), which takes away any retention time errors associated with a change of ambient temperature.

In reverse-phase HPLC, the column stationary phase packing is usually either a C4, C8, or C18 packing. The C4 columns are primarily for proteins with large molecular weights, whereas the C18 columns are for peptides and basic samples with lower molecular weights.

Detection by absorption spectroscopy is overwhelmingly the detection method of choice, as the absorption spectra of the components are all readily available. Some systems use electrochemical measurements, such as conductivity or amperometry, as their detection method.

For this experiment, the mobile phase is primarily 20% acetonitrile and 80% purified deionized (DI) water. A small amount of acetic acid is added to lower the pH of the mobile phase, which keeps the silanol in the stationary packing phase in an undissociated state. This reduces the adsorption peak from tailing, giving narrower peaks. Then, the pH is adjusted with 40% sodium hydroxide to raise the pH and help decrease the retention times of the components.

Each group uses a set of the 7 vials containing different concentrations of the standard solutions (Table 1). The first 3 are used to identify each peak, and the last 4 are for creating a calibration chart for each component. Standards 1–3 are also used for the calibration chart.

| Number | Caffeine (mL) | Benzoate (mL) | Aspartame (mL) |

| 1 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 |

| 3 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 4 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| 6 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| 7 | 5 | 5 | 5 |

Table 1. Volumes of stock standards used to prepare the 7 provided working standards (total volume of each standard is 50 mL).

1. Making the Mobile Phase

- Prepare the mobile phase by adding 400 mL of acetonitrile to approximately 1.5 L of purified DI water.

- Carefully add 2.4 mL of glacial acetic acid to this solution.

- Dilute the solution to a total volume of 2.0 L in a volumetric flask with purified DI water. The resulting solution should have a pH between 2.8 to 3.2.

- Adjust the pH to 4.2 by adding 40% sodium hydroxide, drop-wise with the use of a calibrated digital pH meter. Add very slowly once the pH reaches 4.0. This should take around 50 drops to accomplish.

- Filter the mobile phase through a 0.47-µm Nylon 66 membrane filter under vacuum to degas the solution and to remove solids that could plug the chromatographic column. It is important to degas the mobile phase to avoid having a bubble, which could either cause a void in the stationary phase at the inlet of the column or work its way into the detector cell, causing instability with the UV absorbance.

2. Creating the Component Solutions

The three components that need to be made are caffeine (0.8 mg/mL), potassium benzoate (1.4 mg/mL), and aspartame (L-aspartyl-L-phenylalanine methyl ester) (6.0 mg/mL). These concentrations, once diluted in the same fashion, put the standards at the levels found in the soda samples.

- Add 0.40 g of caffeine to a 500-mL volumetric flask, then dilute to the 500-mL mark with DI water.

- Add 0.70 g of benzoate to a 500-mL volumetric flask, then dilute to the 500-mL mark with DI water.

- Add 0.60 g of aspartame to a 100-mL volumetric flask, then dilute to the 100-mL mark with DI water. Place this solution in a refrigerator to avoid decomposition during storage.

3. Making the 7 Standard Solutions

The three components all have differing distribution coefficients, which affects how each interacts with both of the phases. The larger the distribution coefficient, the more time the component spends in the stationary phase, resulting in longer retention times in reaching the detector.

- Following the chart in Table 1, pipet the proper amount of each component into a 50-mL volumetric flask.

- Dilute each of the stock solutions to the 50-mL mark on the volumetric flasks with mobile phase.

- Pour each standard solution into labeled small vials in a sample rack.

- Store the racks of samples in a refrigerator, along with the remaining solutions in the 50-mL volumetric flasks.

4. Checking the Initial Settings of the HPLC System

- Confirm that the waste line is in a waste container and is not recycling back into the mobile phase.

- Verify that the flow rate of the mobile phase is set to 0.5 mL/min. This is high enough to allow all peaks to elute within 5 min and slow enough to allow for nice resolution.

- Verify that the minimum and maximum pressure and the flow rate are set to the correct values on the front panel of the solvent delivery system (the pump).

- Minimum pressure setting: 250 psi (this is to shut off the pump, if a leak occurs).

- Maximum pressure setting: 4,000 psi (this is to protect the pump from breaking, if a clog forms).

- Press "zero" on the detector's front panel in order to set the blank (the blank is the pure mobile phase).

- Rinse a 100-µL syringe with deionized water, then with several volumes of one of the working standards to be analyzed, and fill the syringe with that solution. Start with the 3 single-component samples, which allows for identifying the peak of each component of interest.

5. Manually Injecting the Sample and Data Collection

- With the injector handle in the load position, slowly inject 100 µL of solution through the septum port.

- Verify that the data collection program is set to collect data for 300 s, which allows enough time for all 3 peaks to elute through the detector.

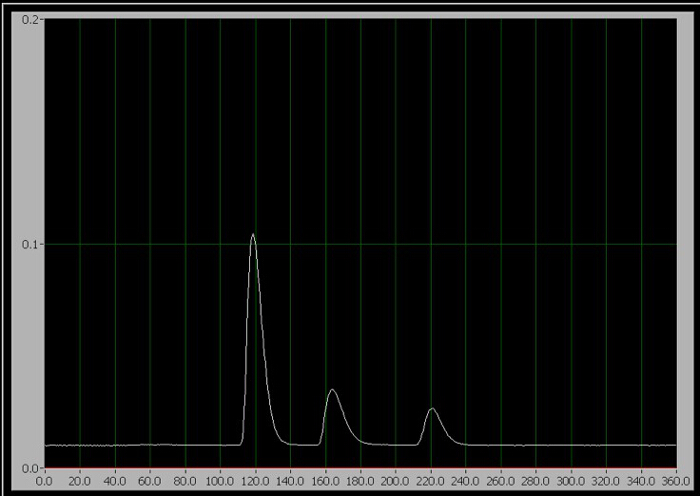

- When ready to start the trial, rotate the injector handle to the inject position (which injects the sample into the mobile phase) and click "Start Trial" on the computer data collection program immediately. For standards 1-3, only one of the three sequential peaks appear on the screen during the run (Figure 1).

- Once 300 s have passed, the data collection sends a prompt to save the data file. Save the data under a suitable file name (e.g., STD#1).

- Note the time in seconds for the peak of each trial, which is used in identifying that component.

- Remove the syringe from the septum and repeat the process for each of the remaining working standards, using the same time per chromatogram as determined from the first run.

Figure 1. The chromatogram of the 3 components. From left to right, they are caffeine, aspartame, and benzoate.

6. The Samples of Diet Sodas

Diet Coke, Diet Pepsi, and Coke Zero are the "unknowns." They have been left out in open containers overnight to get rid of the carbonation, as bubbles are not good for the HPLC system. This sufficiently gets rid of any gases in the samples.

- Draw around 2 mL of the diet soda into a plastic syringe.

- Attach the filter tip to the syringe via Luer-Lok by twisting it in place.

- Push the liquid in the syringe through the filter and into a small glass vial. This gets rid of unwanted particulates that could potentially clog the separation column.

- Dilute each sample with an equal amount of DI water, so they are at 50% purity.

- Inject 100 µL of the sample into the sample loop, and run trials with the same parameters as for the standards.

7. Calculations

- From the concentrations of the component solutions, calculate the concentration of all of the components in the standards, based upon the dilutions that were made for the 7 samples.

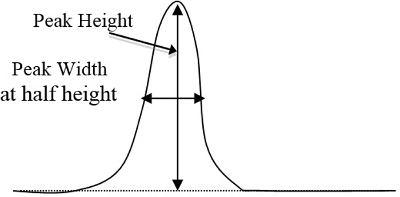

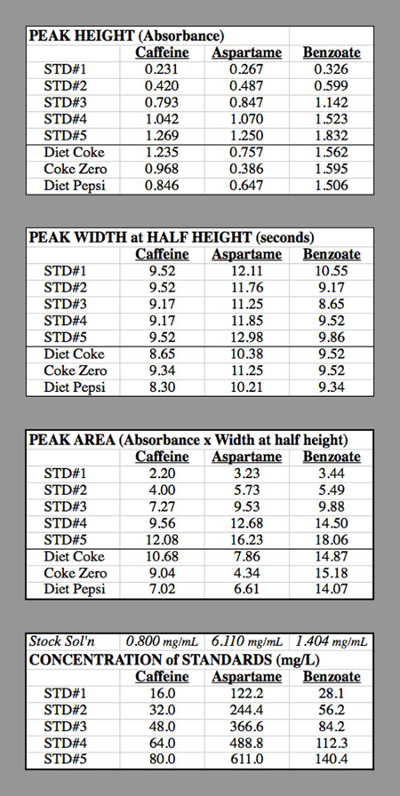

- Determine peak areas on the chromatograms for each standard and the unknown samples by the triangular method, which equals peak height times the width at ½ height (Figure 2). After determining which peak corresponds to each component based upon the time it takes for each component to show their respective peak, enter these peak areas into a computer spreadsheet.

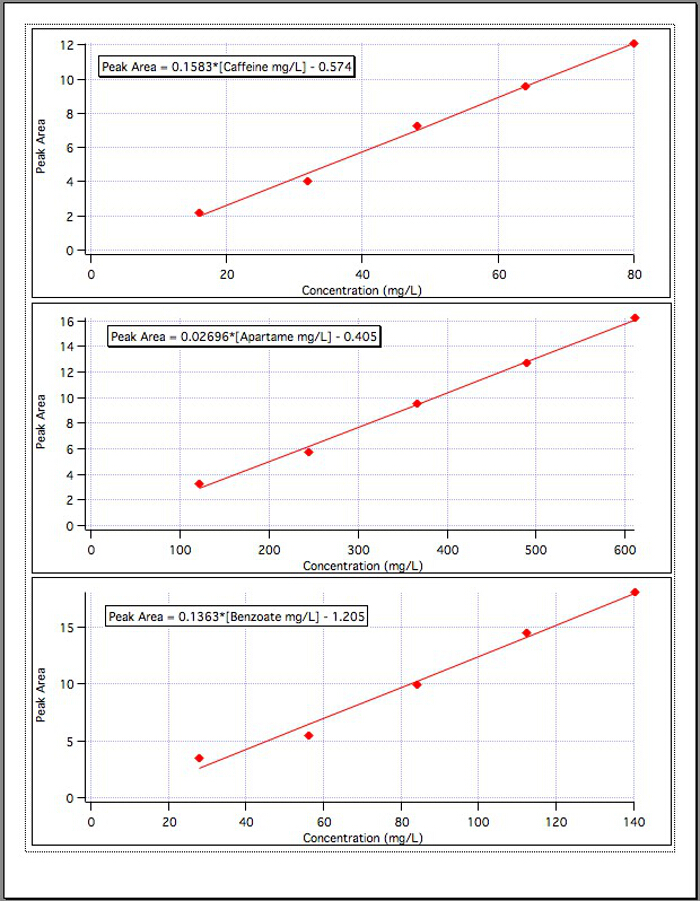

- Create calibration curves of peak area vs. concentration (mg/L) in the standards for all three components.

- Determine the least-squares fit for each calibration curve.

- Calculate the concentration of each component in the diet sodas from the peak areas shown from the HPLC trials for the samples. Remember that the diet soda was diluted by a factor of 2 prior to injecting into the HPLC system.

- Calculate the amount, in mg/L, of each component in the diet sodas.

- Based upon the results, calculate the milligrams of each component found in a 12-oz can of soda. Assume 12 oz = 354.9 mL.

Figure 2. A basic example of a curve's peak height and width, which are to be multiplied (peak height times width at ½ height).

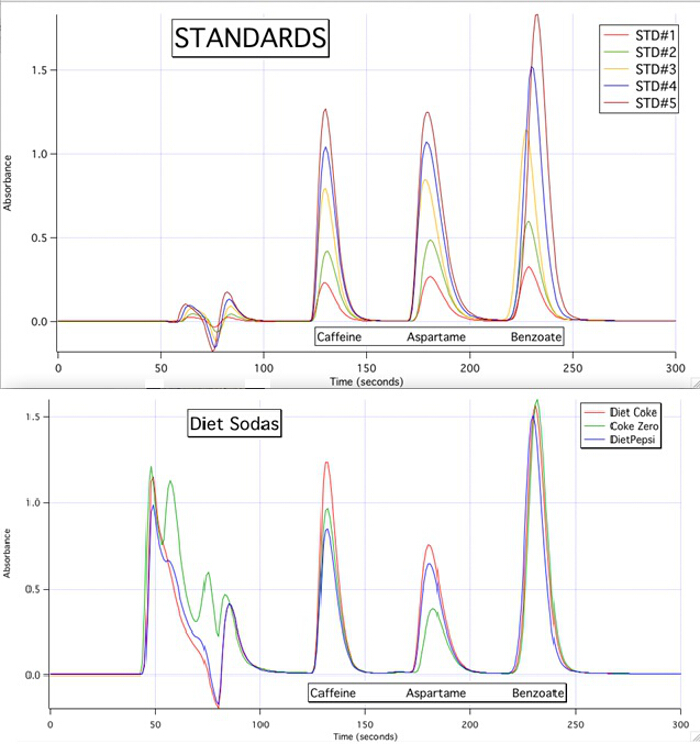

The HPLC chromatograms are able to quantify each of the 3 components for all the samples based upon the calibration curves of the standards (Figure 3).

From this set of experiments, it was determined that a 12-oz can of these diet sodas contained the following amounts of each component:

Diet Coke: 50.5 mg caffeine; 217.6 mg aspartame; 83.6 mg benzoate.

Coke Zero: 43.1 mg caffeine; 124.9 mg aspartame; 85.3 mg benzoate.

Diet Pepsi: 34.1 mg caffeine; 184.7 mg aspartame; 79.5 mg benzoate.

Not surprisingly, all 3 had roughly the same amount of benzoate, as it is just a preservative. The Coke products had a bit more caffeine, and the Coke Zero had much less aspartame than the other two sodas, as it also includes citric acid for some flavoring.

The following numbers are the actual amounts of caffeine and aspartame in a 12-oz can of the 3 diet sodas (The caffeine content was obtained from the Coca-Cola and Pepsi websites. The aspartame content was obtained from both LiveStrong.com and DiabetesSelfManagement.com.):

Diet Coke: 46 mg caffeine; 187.5 mg aspartame

Coke Zero: 34 mg caffeine; 87.0 mg aspartame

Diet Pepsi: 35 mg caffeine; 177.0 mg aspartame

Sample Calculations (Table 2):

Concentration of caffeine in STD#1: The component solution for caffeine had 0.400 g of caffeine diluted to 500 mL = 0.500 L → 0.800 g/L = 0.800 mg/mL.

STD#1 had 1 mL of this solution diluted to 50.0 mL

0.800 mg/mL * (1.0 mL / 50.0 mL) = 0.016 mg/mL = 16.0 mg/L.

STD#2 had 2 mL of this solution diluted to 50.0 mL

0.800 mg/mL * (2.0 mL / 50.0 mL) = 0.032 mg/mL = 32.0 mg/L.

The results from the three calibration graphs (Figure 4) yielded the following equations:

Caffeine Peak Area = 0.1583*[Caffeine mg/L] - 0.574

Aspartame Peak Area = 0.02696*[Aspartame mg/L] - 0.405

Benzoate Peak Area = 0.1363*[Benzoate mg/L] - 1.192

Diet Coke: Caffeine Peak Area = 10.68 = 0.1583*[Caffeine mg/L] - 0.574

[Caffeine mg/L] = (10.68 + 0.574)/ (0.1583) = 71.1 mg/L in the injected sample.

Since the sample was diluted by a factor of 2, the Diet Coke had 141.2 mg/L caffeine.

The amount per 12-oz can = (141.2 mg/L)(0.3549 mL/12-oz can) = 50.5 mg caffeine/can.

Figure 3. The HPLC chromatograms of the 5 standards and the 3 samples.

Figure 4. The calibration curves for each of the 3 components.

Table 2. The data tables for the HPLC trials used for generating the calibration curves.

HPLC is a widely-used technique in the separation and detection for many applications. It is ideal for non-volatile compounds, as gas chromatography (GC) requires that the samples are in their gas phase. Non-volatile compounds include sugars, vitamins, drugs, and metabolites. Also, it is non-destructive, which allows each component to be collected for further analysis (such as mass spectrometry). The mobile phases are practically unlimited, which allows changes to the polarity of pH to achieve better resolution. The use of gradient mobile phases allows for these changes during the actual trials.

There has been concern over the possible health issues that may be associated with the artificial sweetener aspartame. Current product labeling does not show the amount of these components inside of the diet beverages. This method allows for quantifying these amounts, along with the caffeine and benzoate.

Other applications include determining the amounts of pesticides in water; determining the amount of acetaminophen or ibuprofen in pain reliever tablets; determining whether there are performance-enhancing drugs present in the bloodstream of athletes; or simply determining the presence of drugs in a crime lab. While the concentrations of these samples, and often the identity of the components, can be readily determined, the one limitation is that several samples could have close to identical retention times, resulting in co-eluting.

Skip to...

Videos from this collection:

Now Playing

High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC)

Analytical Chemistry

381.2K Views

Sample Preparation for Analytical Characterization

Analytical Chemistry

83.4K Views

Internal Standards

Analytical Chemistry

203.1K Views

Method of Standard Addition

Analytical Chemistry

318.5K Views

Calibration Curves

Analytical Chemistry

788.3K Views

Ultraviolet-Visible (UV-Vis) Spectroscopy

Analytical Chemistry

615.6K Views

Raman Spectroscopy for Chemical Analysis

Analytical Chemistry

50.7K Views

X-ray Fluorescence (XRF)

Analytical Chemistry

25.2K Views

Gas Chromatography (GC) with Flame-Ionization Detection

Analytical Chemistry

279.4K Views

Ion-Exchange Chromatography

Analytical Chemistry

262.7K Views

Capillary Electrophoresis (CE)

Analytical Chemistry

92.9K Views

Introduction to Mass Spectrometry

Analytical Chemistry

111.1K Views

Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

Analytical Chemistry

86.4K Views

Electrochemical Measurements of Supported Catalysts Using a Potentiostat/Galvanostat

Analytical Chemistry

51.2K Views

Cyclic Voltammetry (CV)

Analytical Chemistry

123.1K Views

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved