1. Make a set of word lists.

- To make stimuli for this experiment, gather 40 index cards and a pen.

- Generate a random list of 210 common nouns, words like, car, dog, pen, boat, chair, and hammer.

- Each index card will include three, four, five, six, seven, eight, or nine common nouns on it. Make five cards with each number. Don’t repeat nouns from list to list, and try not to have them group together by category. For example, avoid lists with only animals or tools or foods. Instead, try to make sure the lists are mixed, with a variety of content types on each. A sample list of three words might include bowl, table, and saw and a sample list for five might include: shelf, deer, jelly, book, and flame.

2. Test a participant.

- Place your index cards face down on a table between you and the participant, organized into piles for each number of words.

- Explain the instructions: On each trial, the experimenter will pick up one of the cards, slowly read the words on the card in order from top to bottom, and as soon as the experimenter finishes the participant will need to repeat the list, in the same order.

- Start with the top card on the three-word pile, complete that pile, and work your way up.

- As the participant responds note on the relevant card whether a word was repeated back correctly by placing a check mark next to a word when the participant says it, or an ‘X’ if she fails to, or says something else in its place. The words need to be reported back in the right order.

- The experiment is done when you get through all the lists.

3. Perform the analysis.

- If you go back the index cards, you have a record of whether each word in a list was recalled correctly or not.

- The most informative way to analyze these results is in terms of the number of words in a list, and a given word’s position in a list. For all the cards with three words, for example, you can compute the probability that the first word was recalled correctly, and the same for the second and third words. Do this for all the lists, and input the results into a spreadsheet (Table 1).

- For graphing purposes, translate Table 1 into a more compact summary of accuracy as a function of word position and list length (Table 2).

| List Length |

Word Position |

Number correct |

Percent Correct |

| 3 |

1 |

5 |

100 |

| 3 |

2 |

5 |

100 |

| 3 |

3 |

5 |

100 |

| 4 |

1 |

5 |

100 |

| 4 |

2 |

4 |

80 |

| 4 |

3 |

5 |

100 |

| 4 |

4 |

5 |

100 |

| 5 |

1 |

5 |

100 |

| 5 |

2 |

4 |

80 |

| 5 |

3 |

4 |

80 |

| 5 |

4 |

5 |

100 |

| 5 |

5 |

5 |

100 |

| 6 |

1 |

4 |

80 |

| 6 |

2 |

4 |

80 |

| 6 |

3 |

3 |

60 |

| 6 |

4 |

3 |

60 |

| 6 |

5 |

3 |

60 |

| 6 |

6 |

5 |

100 |

| 7 |

1 |

4 |

80 |

| 7 |

2 |

2 |

40 |

| 7 |

3 |

3 |

60 |

| 7 |

4 |

2 |

40 |

| 7 |

5 |

2 |

40 |

| 7 |

6 |

3 |

60 |

| 7 |

7 |

4 |

80 |

| 8 |

1 |

5 |

100 |

| 8 |

2 |

3 |

60 |

| 8 |

3 |

3 |

60 |

| 8 |

4 |

1 |

20 |

| 8 |

5 |

3 |

60 |

| 8 |

6 |

2 |

40 |

| 8 |

7 |

3 |

60 |

| 8 |

8 |

4 |

80 |

| 9 |

1 |

4 |

80 |

| 9 |

2 |

3 |

60 |

| 9 |

3 |

1 |

20 |

| 9 |

4 |

3 |

60 |

| 9 |

5 |

2 |

40 |

| 9 |

6 |

1 |

20 |

| 9 |

7 |

3 |

60 |

| 9 |

8 |

3 |

60 |

| 9 |

9 |

4 |

80 |

Table 1. List learning results. Example data from one participant. Recall that there were five cards for each list length. For a given word position and given list length, the participant had five opportunities. Percentage correct is thus the number of correct responses out of five.

|

Position |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Length |

1 |

2 |

3 |

4 |

5 |

6 |

7 |

8 |

9 |

| 3 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| 4 |

100 |

80 |

100 |

100 |

|

|

|

|

|

| 5 |

100 |

80 |

80 |

100 |

100 |

|

|

|

|

| 6 |

80 |

80 |

60 |

60 |

60 |

100 |

|

|

|

| 7 |

80 |

40 |

60 |

40 |

40 |

60 |

80 |

|

|

| 8 |

100 |

60 |

60 |

20 |

60 |

40 |

60 |

80 |

|

| 9 |

80 |

60 |

20 |

60 |

40 |

20 |

60 |

60 |

80 |

Table 2. Summary of list learning results. The data are summarized in terms of response accuracy as a function of a word’s position in a list and the length of the list.

To actively remember information over a short duration, Individuals rely on a specialized memory system called working memory.

Unlike long-term memory, working memory has a very limited capacity, which allows selective information to remain active-to be studied, manipulated, and then transferred to other memory and cognitive systems.

Researchers can measure the capacity limit of verbal working memory-the memory span-through the use of a verbal list paradigm. This paradigm involves the researcher reading word lists of varied lengths to subjects and then asking the subjects to repeat back the words in sequential order.

This video demonstrates standard procedures for studying verbal working memory span by explaining how to design and conduct the experiment, as well as how to analyze and interpret the results.

In this experiment, participants listen as an experimenter reads word lists with varying lengths. In this case, word positions among the varied-length lists are the independent variables.

Participants are then asked to hold words in working memory while a list is read, after which they are asked to recall the words on the list in the same order. Recall accuracy, or how many words on the list are repeated back in the correct order, is the dependent variable.

At the beginning of the list, words are mentally rehearsed more than those in latter positions. Therefore, higher recall accuracy is hypothesized for words in the primary positions. Such performance is referred to as a primacy effect.

In contrast, when longer lists need to be recalled, contents of verbal working memory interfere with each other. Thus, the words in the middle of a list are recalled with greater difficulty, because they have more neighbors.

Since words at the end of the list were heard most recently and have few interfering neighbors, they are expected to be recalled with high accuracy. This aspect of verbal working memory is referred to as the recency effect.

Finally, verbal working memory span is classified by identifying the longest list for which participants performed better than 75% correct across all word positions.

To conduct this study, prepare stimuli by generating a random word list of 210 common nouns, such as car, dog, pen, or boat.

From the master list of nouns, create seven varied-length piles, each containing five index cards with different nouns written on each one. Thus, for the first stack, start by writing three of the generated nouns, and increase the number of words for each stack until you have a list length of nine.

To finalize the word lists, verify that no nouns are repeated across the lists or clustered into categories that would unintentionally make recall easier. Arrange the stacks into piles of increasing order-from shortest to longest-and place facedown.

To begin the experiment, greet the participant and have them take a seat facing you, with the pile of index cards placed in front of you. Explain the instructions to the participant, providing details on how they should remember the words read to them and then repeat the list back in the proper order.

First, pick up a card and slowly read the words out loud in order from top to bottom. When you reach the end of the list, say 'Go.'

As the participant recites the list back, follow along on the card and mark whether each word was repeated back correctly or incorrectly in the right order by placing a checkmark or X, respectively.

Make sure to go through all cards in each pile before moving on to the next one. Complete the session with the longest list.

To analyze the data, tally the results based on the number of words and the position of each word in the list for all of cards in each set. Remember that there were five total responses for each position.

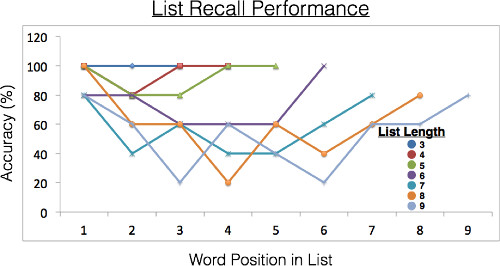

To visualize list recall performance, plot percent correct as a function of word position by list length. Notice that recall is more accurate for words positioned in the beginning and end of the lists than the middle words, confirming the primacy and recency effects in verbal working memory.

To calculate working memory span, summarize percent correct as a function of list length and word position. Identify the longest list for which a participant performed better than 75% correct for all word positions.

Now that you are familiar with designing a verbal list paradigm, you can apply this approach to answer specific questions about working memory function.

Working memory is engaged on a daily basis, for recalling detailed steps to a favorite recipe, or trying to remember the names of several new people at a social function.

In addition, memory span is included as a component of many intelligence tests, as the measure correlates very reliably with IQ.

Such correlations also allow memory span to be used with functional imaging to determine whether brain damage impacts cognitive functioning in general, or as an indicator for degenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's.

You've just watched JoVE's introduction on verbal working memory span. Now you should have a good understanding of how to design and conduct the experiment, as well as how to analyze results and apply the phenomenon.

Thanks for watching!