A subscription to JoVE is required to view this content. Sign in or start your free trial.

Method Article

Evaluating Postural Control and Lower-extremity Muscle Activation in Individuals with Chronic Ankle Instability

In This Article

Summary

Individuals with chronic ankle instability (CAI) exhibit postural control deficiency and delayed muscle activation of lower extremities. Computerized dynamic posturography combined with surface electromyography provides insights into the coordination of the visual, somatosensory, and vestibular systems with muscle activation regulation to maintain postural stability in individuals with CAI.

Abstract

Computerized dynamic posturography (CDP) is an objective technique for the evaluation of postural stability under static and dynamic conditions and perturbation. CDP is based on the inverted pendulum model that traces the interrelationship between the center of pressure and the center of gravity. CDP can be used to analyze the proportions of vision, proprioception, and vestibular sensation to maintain postural stability. The following characters define chronic ankle instability (CAI): persistent ankle pain, swelling, the feeling of “giving way,” and self-reported disability. Postural stability and fibular muscle activation level in individuals with CAI decreased due to lateral ankle ligament complex injuries. Few studies have used CDP to explore the postural stability of individuals with CAI. Studies that investigate postural stability and related muscle activation by using synchronized CDP with surface electromyography are lacking. This CDP protocol includes a sensory organization test (SOT), a motor control test (MCT), and an adaption test (ADT), as well as tests that measure unilateral stance (US) and limit of stability (LOS). The surface electromyography system is synchronized with CDP to collect data on lower limb muscle activation during measurement. This protocol presents a novel approach for evaluating the coordination of the visual, somatosensory, and vestibular systems and related muscle activation to maintain postural stability. Moreover, it provides new insights into the neuromuscular control of individuals with CAI when coping with real complex environments.

Introduction

Computerized dynamic posturography (CDP) is an objective technique for the evaluation of postural stability under static and dynamic conditions and perturbation. CDP is based on the inverted pendulum model that traces the interrelationship between the center of pressure (COP) and the center of gravity (COG). COG is the vertical projection of the center of mass (COM), whereas COM is the point equivalent of the total body mass in the global reference system. COP is the point location of the vertical ground reaction force vector. It represents a weighted average of all the pressures over the surface of the contact area with the ground1. Postural stability is the ability to maintain the COM within the base of support in a given sensory environment. It reflects neuromuscular control ability that coordinates the central nervous system with the afferent sensory system (vision, proprioception, and vestibular sensation) and motor command output2.

Previous evaluation methods for postural control, such as the time for a single-leg stance and the reach distance for Y-balance tests, are results-oriented and cannot be used to objectively evaluate the coordination between sensory systems and motor control3. In addition, some studies used portable computerized wobble board, which quantified dynamic balance performances out of laboratory settings4,5,6. CDP differs from the abovementioned test methods, because it can be applied to the analysis of the proportion of vision, proprioception, and vestibular sensation in postural stability maintenance and to the evaluation of the proportion of motor strategy, such as ankle or hip dominant strategy. It has been viewed as a gold standard for postural control measurement7 because of its accuracy, reliability, and validity8.

Chronic ankle instability (CAI) is characterized by persistent ankle pain, swelling, and feeling of “giving way”; it is one of the most common sports injuries9. CAI originates mostly from lateral ankle sprains, which destroy the integrity and stability of the lateral ankle ligament complex. The proprioception, fibular muscle strength, and normal trajectory of talus are impaired10,11. The deficiencies of the weak ankle segment can result in deficient postural control and muscle activation in individuals with CAI12. However, few studies have investigated the postural stability of individuals with CAI by using CDP3,13. Current measurements could rarely analyze the posture control deficiency of CAI from the perspective of sensory analysis. Therefore, the ability of sensory organization and postural strategy of CAI to maintain postural stability needs further exploration.

Muscle activity is an important component of neuromuscular control that affects the regulation of postural stability14,15. However, CDP only monitors the interrelationship between COP and COG through force plates, and its application to the observation of the specific activation level of lower limb muscles in individuals with CAI is difficult. Currently, few studies have evaluated the postural stability of individuals with CAI through a method that combines CDP with electromyography (EMG).

Therefore, the developed protocol aims to explore postural control and related muscle activity by combining CDP and surface electromyography system (sEMG). This protocol provides a novel approach to investigate neuromuscular control, including sensory organization, postural control, and related muscle activity, for participants with CAI.

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Protocol

Prior to tests, the participants signed an informed consent after receiving information about the experimental process. This experiment has been approved by the ethics committee of Shanghai University of Sports.

1. Equipment setup

- Turn on the CDP system, complete self-calibration, and ensure that the instrument operates normally at 100 Hz sampling frequency.

NOTE: Each of the two installed independent force plates measures three forces (Fx, Fy, and Fz) and three moments (Mx, My, and Mz). The x-axis is in the left–right direction and is perpendicular to the sagittal plane. The y-axis is in the forward–backward direction and is perpendicular to the coronal plane. The z-axis is perpendicular to the horizontal plane. The origins are located at the centers of the force plates. - Double-click Balance Manager System | Clinical Module, and then click New Patient and establish the patient ID. Input an accurate height, weight, and age. Select Sensory Organization Test, Unilateral Stance, Limits of Stability, Motor Control Test, and Adaption Test.

NOTE: Such demographic data are also used for age-matched normative diagnostic analysis. - Turn on the surface electromyography (sEMG) system, and double click the EMG Motion Tools icon. Specify the trigger signal as Trigger In (Manual Stop), establish the participant ID, and match the measured muscles with the wireless electrode. The muscles of unstable lower limb are vastus medialis (VM), vastus lateralis (VL), biceps femoris (BF), tibialis anterior (TA), peroneal longus (PL), gastrocnemius medialis (GM), and gastrocnemius lateralis (GL).

NOTE: The phrase Trigger In (Manual Stop) indicates that CDP triggers the sEMG system to capture EMG data during tests, but the "end" flag requires manual clicking to stop the acquisition. - Connect sEMG system with CDP system through the synchronization line. Adjust the camera of sEMG system to capture the signal indicator light of the CDP system.

NOTE: The video of the indicator light is collected synchronously with the CDP system and sEMG to cut the corresponding cycle of the EMG in accordance with the CDP tests. “Light on” indicates that the test is in progress, and “light off” indicates that the test is paused/stopped.

2. Participant selection and preparation

- Use the following inclusion criteria for CAI participants: (1) 35 male participants with regular daily activity, excluding professional athletes or sedentary participants; (2) 20–29 years old; (3) history of at least one significant ankle sprain, and the initial sprain must have occurred at least 12 months before enrollment in the study; (4) feelings of “giving away” of the injured ankle joint and/or recurrent sprain and/or “feeling of instability;” and (5) a Cumberland Ankle Instability Tool questionnaire score of less than 24 points16.

- Exclude participants with a history of bilateral sprains, lower limb fracture, operation, nervous and vestibular system diseases, or allergy to taping. Additionally, recruit 35 male participants without CAI, whose demographic data matched with the CAI group, as the control group.

- For preparation, fix the electrode piece on the belly of the measured muscles. Instruct the participants to wear a safety harness and stand barefoot on the force plates to face the visual surround.

- Adjust the alignment of the feet on the force plates. Align the malleolus medialis with the horizontal line and lateral edge of foot with the corresponding computer-generated height line (S, M, and T lines). Turn off the screen embedded in the visual surround (Figure 1).

NOTE: These guidelines are based on the following heights. “S” means “small” and includes heights ranging from 76 cm to 140 cm. “M” means “medium” and includes heights ranging from 141 cm to 165 cm. “T” means “tall” and includes heights ranging from 166 cm to 203 cm. The screen may produce learning effects, because it can provide real-time visual feedback. Thus, the screen should remain closed during the test, except during the limit of stability (LOS) test17.

- Adjust the alignment of the feet on the force plates. Align the malleolus medialis with the horizontal line and lateral edge of foot with the corresponding computer-generated height line (S, M, and T lines). Turn off the screen embedded in the visual surround (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Participant preparation for measurement. The participants stand upright barefoot to face the visual surround, wear safety harness, correctly align their feet with the force plates, and fix the wireless EMG electrodes on their legs. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

3. Measurement procedures

- CDP measurement

- Sensory organization test

- Instruct the participants to stand upright and to keep their COG as stable as possible to cope with the interference from vision, somatosensory, and vestibular sensation (singly or combined) (Table 1). Complete the measurements of conditions 1–6. Each test lasts for 20 s. Repeat the procedure thrice for each condition.

- Unilateral stance

- Instruct the participants to place their hands on the anterior superior iliac spine with their eyes open/closed. Consider the unstable ankle side as the support leg. Fully extend their knee joint, and bend the knee of their non-supporting leg by approximately 30°. Allow the participants to remain standing stably for 10 s. Repeat the procedure thrice for each visual condition.

- Limit of stability

- Instruct the participants to maintain their COG in the central area. Upon hearing the ring, lean their body and shift their COG quickly into the targeted frame in the screen. Instruct the participants to remain steady for 10 s. Complete the eight directional shifting of their COG (forward, forward-right, right, right-backward, backward, backward-left, left, and left-forward).

NOTE: In the process of COG shifting, the body is kept straight, the heel or toes are not far from the force plates, and the hip joint is not bent.

- Instruct the participants to maintain their COG in the central area. Upon hearing the ring, lean their body and shift their COG quickly into the targeted frame in the screen. Instruct the participants to remain steady for 10 s. Complete the eight directional shifting of their COG (forward, forward-right, right, right-backward, backward, backward-left, left, and left-forward).

- Motor control test

- Instruct the participants to respond effectively to restore body stability and to cope with the unexpected slipping of the force plates. Repeat the procedure thrice for each slip condition.

NOTE: The force plates are slipped with small/medium/large amplitude in the anterior/posterior direction. According to the participant’s height, the slip amplitude of the force plates is automatically adjusted. Standard procedures must be followed to align the foot position on the force plates. Random delay exists between trials.

- Instruct the participants to respond effectively to restore body stability and to cope with the unexpected slipping of the force plates. Repeat the procedure thrice for each slip condition.

- Adaption test

- Instruct the participants to respond effectively to restore body stability and to cope with five consecutive unexpected rotations at a velocity of 20°/s. Direct the toes upward or downward.

- Sensory organization test

| Condition | Eyes | Force plates | Visual surround | Interference | Anticipated Response |

| 1 | Open | Fix | Fix | Somatosensory | |

| 2 | Close | Fix | Fix | Vision | Somatosensory |

| 3 | Open | Fix | Sway-reference | Vision | Somatosensory |

| 4 | Open | Sway-reference | Fix | Somatosensory | Vision, vestibular |

| 5 | Close | Sway-reference | Fix | Somatosensory, vision | Vestibular |

| 6 | Open | Sway-reference | Sway-reference | Somatosensory, vision | Vestibular |

Table 1: Different interference and corresponding anticipated response in sensory organization test. The term “sway-referenced” means that the movement of the force plates and visual surround follows the participant’s COG sway.

- sEMG measurement and data process

- After triggering by CDP system during SOT, US, LOS, MCT and ADT, start the automatic acquisition of lower-limb muscle activity raw data. Manually stop the acquisition during the sEMG system when the light is off. The sample size is 1000 Hz.

- Enter the processing window of the sEMG software. Import the C3d file of the EMG raw data and mp4 file of the light video. Cut the trial cycle when the light is on.

- In the “processing pipeline” operations, include the following options in the run pipeline: Butterworth filter with low-pass (450 Hz, 2. Order) and high-pass (20 Hz, 2. Order); notch filter at 50 Hz; and root mean square smoothing window of 100 ms.

NOTE: Choose the Butterworth filter with low-pass (450 Hz, 2. Order) and high-pass (20 Hz, 2. Order) to filter out unwanted low and high-frequency components. Set the notch filter at 50 Hz to remove 50 Hz interference from the main power. Use the root mean square smoothing window of 100 ms to smooth the noisy signal. - In the Generate Events options, include the following events in the run pipeline. “muscle on” is defined as “all channels go above 5x baseline noise standard deviations for at least 50 ms”. “muscle off” is defined as “all channels drop below 5x standard deviations over baseline for at least 50 ms ”.

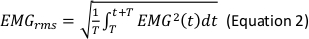

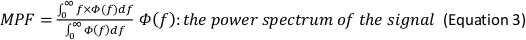

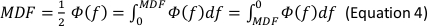

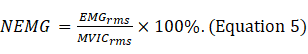

- In the Generate Parameters options, include the following parameters in the run pipeline: integral electromyography (iEMG); root mean square (RMS); mean power frequency (MPF); medium frequency (MDF); and co-activation ratio.

NOTE: The following are the referenced calculation formulas for the above parameters (Equations 1–4):

- Normalize the RMS values of the SOT, US, LOS, MCT and ADT trials with the RMS values of maximal voluntary isometric contraction (MVIC) for each muscle (Equation 5).

NOTE: MVIC indicates the maximum force contraction of each muscle for participants in the standard posture for 5 s (Supplementary file 1)18.

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Results

Representative CDP Results

Sensory organization test

The system evaluates the participant’s ability to maintain COG in the predetermined target area, when the environment changes as the peripheral signal input. Equilibrium score (ES) is the score under conditions 1–6 that reflects the ability to coordinate the sensory system to maintain postural stability (Equation 6). The composite score (COMP) is the weighted average score of al...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Discussion

The presented protocol is used to measure dynamic postural control and related muscle activity in individuals with CAI by synchronizing CDP with sEMG. CDP traces the trajectory of the COP and COG and provides insight into the interaction between sensory information (visual, somatosensory, and vestibular sensation) input and the external environment8,21,22. It is an effective tool for the diagnosis of the functional activity limi...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funding of National Natural Science Fund of China (11572202, 11772201, and 31700815).

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| NeuroCom Balance Manager SMART EquiTest | Natus Medical Incorporated, USA | Its major components include: NeuroCom Balance Manager Software Suite, dynamic dual force plate (rotate & translate), moveable visual surround with 15” LCD display (it could provide a real time display of the subject’s center of gravity shown as a cursor during the task) and illumination, overhead support bar with patient harness, computer and other parts. | |

| wireless Myon 320 sEMG system | Myon AG | The system consists of 16 parallel channels of transmitter signals, receiver, "EMG motion Tools" and "ProEMG" software,computer and other parts. |

References

- Winter, D. A. Human balance and posture control during standing and walking. Gait & Posture. 3, 193-214 (1995).

- Vanicek, N., King, S. A., Gohil, R., Chetter, I. C., Coughlin, P. A. Computerized dynamic posturography for postural control assessment in patients with intermittent claudication. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (82), e51077(2013).

- Yin, L., Wang, L. Acute Effect of Kinesiology Taping on Postural Stability in Individuals With Unilateral Chronic Ankle Instability. Frontiers in Physiology. 11, 192(2020).

- Fusco, A., et al. Dynamic Balance Evaluation: Reliability and Validity of a Computerized Wobble Board. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 34 (6), 1709-1715 (2020).

- Fusco, A., et al. Wobble board balance assessment in subjects with chronic ankle instability. Gait & Posture. 68, 352-356 (2019).

- Silva Pde, B., Oliveira, A. S., Mrachacz-Kersting, N., Laessoe, U., Kersting, U. G. Strategies for equilibrium maintenance during single leg standing on a wobble board. Gait & Posture. 44, 149-154 (2016).

- Domènech-Vadillo, E., et al. Normative data for static balance testing in healthy individuals using open source computerized posturography. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 276 (1), 41-48 (2019).

- Harro, C. C., Garascia, C. Reliability and validity of computerized force platform measures of balance function in healthy older adults. Journal of Geriatric Physical Therapy. 42 (3), 57-66 (2019).

- Doherty, C., et al. The incidence and prevalence of ankle sprain injury: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective epidemiological studies. Sports Medicine. 44 (1), 123-140 (2014).

- Hertel, J. Sensorimotor deficits with ankle sprains and chronic ankle instability. Clinics in Sports Medicine. 27 (3), 353-370 (2008).

- Munn, J., Sullivan, S. J., Schneiders, A. G. Evidence of sensorimotor deficits in functional ankle instability: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 13 (1), 2-12 (2010).

- Arnold, B. L., De La Motte, S., Linens, S., Ross, S. E. Ankle instability is associated with balance impairments: a meta-analysis. Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise. 41 (5), 1048-1062 (2009).

- de-la-Torre-Domingo, C., Alguacil-Diego, I. M., Molina-Rueda, F., Lopez-Roman, A., Fernandez-Carnero, J. Effect of kinesiology tape on measurements of balance in subjects with chronic ankle instability: a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 96 (12), 2169-2175 (2015).

- Jaber, H., et al. Neuromuscular control of ankle and hip during performance of the star excursion balance test in subjects with and without chronic ankle instability. PLoS One. 13 (8), 0201479(2018).

- Simpson, J. D., Stewart, E. M., Macias, D. M., Chander, H., Knight, A. C. Individuals with chronic ankle instability exhibit dynamic postural stability deficits and altered unilateral landing biomechanics: A systematic review. Phys Ther Sport. 37, 210-219 (2019).

- Gribble, P. A., et al. Selection criteria for patients with chronic ankle instability in controlled research: a position statement of the International Ankle Consortium. Br J Sports Medicine. 48 (13), 1014-1018 (2014).

- Wrisley, D. M., et al. Learning effects of repetitive administrations of the sensory organization test in healthy young adults. Archives of Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 88 (8), 1049-1054 (2007).

- Tabard-Fougère, A., et al. EMG normalization method based on grade 3 of manual muscle testing: Within- and between-day reliability of normalization tasks and application to gait analysis. Gait & Posture. 60, 6-12 (2018).

- Shim, D. B., Song, M. H., Park, H. J. Typical sensory organization test findings and clinical implication in acute vestibular neuritis. Auris Nasus Larynx. 45 (5), 916-921 (2018).

- Nam, G. S., Jung, C. M., Kim, J. H., Son, E. J. Relationship of vertigo and postural instability in patients with vestibular schwannoma. Clinical and Experimental Otorhinolaryngology. 11 (2), 102-108 (2018).

- Faraldo-Garcia, A., Santos-Perez, S., Crujeiras, R., Soto-Varela, A. Postural changes associated with ageing on the sensory organization test and the limits of stability in healthy subjects. Auris Nasus Larynx. 43 (2), 149-154 (2016).

- Gofrit, S. G., et al. The association between video-nystagmography and sensory organization test of computerized dynamic posturography in patients with vestibular symptoms. European Archives of Oto-Rhino-Laryngology. 276 (12), 3513-3517 (2019).

- Gribble, P. A., Hertel, J., Denegar, C. R., Buckley, W. E. The effects of fatigue and chronic ankle instability on dynamic postural control. Journal of Athletic Training. 39 (4), 321-329 (2004).

- Gribble, P. A., Hertel, J., Denegar, C. R. Chronic ankle instability and fatigue create proximal joint alterations during performance of the Star Excursion Balance Test. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 28 (3), 236-242 (2007).

- Le Clair, K., Riach, C. Postural stability measures: what to measure and for how long. Clinical Biomechanics. 11 (3), 176-178 (1996).

- Fusco, A., et al. Y balance test: Are we doing it right. Journal of Science and Medicine in Sport. 23 (2), 194-199 (2020).

- Riemann, B., Davies, G. Limb, sex, and anthropometric factors influencing normative data for the Biodex Balance System SD athlete single leg stability test. Athletic Training & Sports Health Care. 5, 224-232 (2013).

- Chiari, L., Rocchi, L., Cappello, A. Stabilometric parameters are affected by anthropometry and foot placement. Clinical Biomechanics. 17 (9-10), 666-677 (2002).

- Chaudhry, H., Bukiet, B., Ji, Z., Findley, T. Measurement of balance in computer posturography: Comparison of methods--A brief review. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies. 15 (1), 82-91 (2011).

- Hertel, J., Braham, R. A., Hale, S. A., Olmsted-Kramer, L. C. Simplifying the Star Excursion Balance Test Analyses of Subjects With and Without Chronic Ankle Instability. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy. 36 (3), (2006).

- Gribble, P. A., Hertel, J., Plisky, P. Using the Star Excursion Balance Test to assess dynamic postural-control deficits and outcomes in lower extremity injury: a literature and systematic review. Journal of Athletic Training. 47 (3), 339-357 (2012).

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionExplore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved