1. Stimulus design

- The experiment includes two types of trials. In half of the trials—the feature search trials—participants will be asked to find a red bar among blue ones. So render a set of 40 displays, placing the red bar randomly in each, and randomly placing either 3, 6, 9, or 12 blue bars as well. The number of blue bars is the distractor load. There will be equal numbers of trials (10 in this case) for each load.

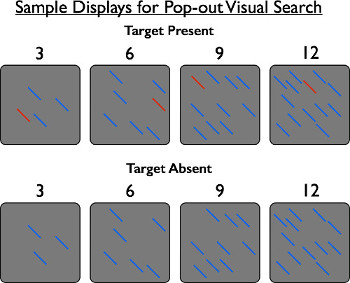

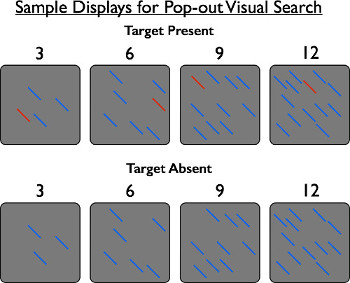

- The experiment also requires target absent trials, trials that do not include the search target, in this case, the red bar. Make 40 of these as well, again, including 10 for each distractor load. The target present and absent trials, by load, should look something like the examples shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Sample displays for pop-out visual search. Top row shows trials with a target, a single red bar, present. The bottom row shows trials without a target, or target absent. The number of non-targets, which are distractors, increases from left to right.

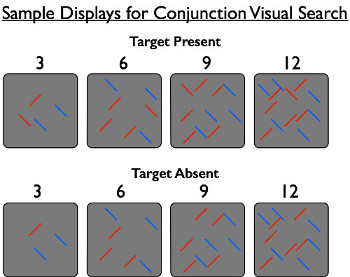

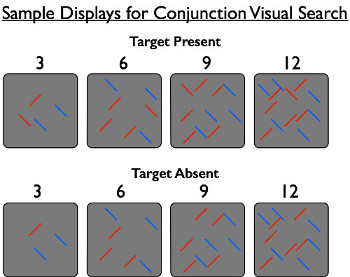

- The other half of the trials will involve conjunction search. In this case, observers will search for a red bar that is oriented at -45°(i.e., tilted to the left, instead of to the right). Again, distractor load will vary, including 3, 6, 9, or 12. But in this case, the distractors will come in two types: blue bars at a -45° angle, and red bars at a +45° angle (i.e., tilted to the right). Each trial will include both kinds of distractors, and again, there will be target absent trials, as well (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Sample displays for conjunction visual search. Top row shows trials with a target, a red bar oriented to the left, present. The bottom row shows trials without a target, or target absent. The number of non-targets, which are distractors, increases from left to right.

2. Procedure

- Run the feature search and conjunction search trials in separate blocks. Some participants perform feature first, and the others do conjunction first. The basic procedure is the same for both types of trials.

- To sequence the experiment, randomly interleave present/absent trials and distractor loads, so that the experiment will comprise a sequence of unpredictable trials.

- On each trial, display stimuli until the participant indicates whether a target is present or absent in that trial. Assign one key, the ‘M’ key to present responses, and the ‘Z’ key to absent responses.

- Have the participant respond as quickly as possible, but without making mistakes.

- Using an experimental software package, such as ePrime, or a programming environment such as MATLAB, record the participant’s response on each trial, along with their response time. This way, you can check that the participant answered correctly, and also see how long they took.

3. Analysis

- At the end of the experiment, output the data into a spreadsheet. Include whether participants answered correctly, their response time, and the parameters of each trial, i.e., was it a present or an absent trial, in the feature or conjunction search block, and with how many distractors.

- Average together the participant’s response times in all of the target present trials, as a function of condition (feature vs. conjunction) and distractor load.

- Note that the results of the target absent trials do not get analyzed. Those are included because, otherwise, the participant could simply hit ‘present’ on each trial without ever finding the target. Look at overall performance though, to make sure the participant was paying attention and trying their best. Generally, if a participant is less than 75% correct on absent trials, their response time data are not analyzed.

- The main analytical questions concern differences in response time between conjunction and feature search trials. Response times should become considerably longer for conjunction search trials as distractor load increases. But they should be relatively unaffected in feature search trials.

Visual attention refers to the ability to focus in on just a part of an image. To study how people attend to objects in cluttered visual scenes, psychologists use a paradigm known as visual search.

Often, visual search experiments can help researchers explain why some objects are easy to find and others more difficult.

Using the visual search paradigm, this video will demonstrate how to design and identify stimuli for experiments, as well as perform, analyze, and interpret results.

To design the stimuli, compose a pair of conditions that are very similar in terms of display contents, but vary in terms of search difficulty. Consider the classic contrasting example between 'Feature Search' and 'Conjunction Search.'

In the Feature Search condition, design trials in which a single feature distinguishes a target amongst its neighbours, known as the distractors. Here, the target is a red bar, and all the distractors are blue bars. The participant should efficiently find the target, as it "pops out" quickly, even when the distractor load increases from three, six, nine, or 12 blue bars.

In the Conjunction Search condition, design trials in which the target shares similarities with distractors. Here, a red target bar is oriented at -45°, and both red and blue distractors are oriented at +45°. In this case, the participant should find the search more difficult because the similarities don't provide a "pop out" effect.

Within each search condition, create two sets of 40 trials where the target is present or absent. Make sure to include 10 trials with each distractor load of three, six, nine, or 12 bars. Randomly interleave all trials to guarantee unpredictable sequences for each search type.

To begin the experiment, start by running the Feature Search and Conjunction Search tasks. Use a counterbalanced design, so that some participants will begin with Feature Search, whereas others will complete Conjunction Search first.

With the participant sitting at the computer, assign the 'M' key to represent target present responses, and the 'Z' key for target absent responses. Indicate to the participant that he or she should press the respective keys to complete each trial as quickly as possible, trying not to make mistakes.

During each trial, capture whether the participant's response was correct or incorrect, as well as the response time. Output the results into a spreadsheet.

After the participant has completed both search types, examine the overall performance for the target absent trials to make sure the participant was paying attention. Exclude any participant who performs less than 75% correct on these trials.

Once criterion performance has been verified, average together each participant's response times for all of the target present trials, as a function of search condition (Feature vs. Conjunction) and distractor load.

The data are then graphed by plotting the mean response times across distractor loads for the feature and conjunction search conditions. The response times for the Feature Search task are relatively unaffected by distractor load. In contrast, Conjunction Search response times increase linearly with distractor load. In addition, both searches take about 200 ms with the minimal of three distractors present. This suggests that a uniform amount of time is necessary to start searching and make a response.

Now that you are familiar with setting up a visual search experiment, you can apply this approach to answer more specific research questions.

One of the main challenges faced by our visual system involves the complex integration of multiple visual features. Finding a red bar among all blue ones is easy because only color information is relevant.

However, when finding an object that has several different features, such as orientation and color, more attention must be used to bind those features together.

For example, researchers apply visual search properties to improve how physicians search for certain telltale signs when they look at an x-ray or MRI scan.

In addition, the visual search approach affects how TSA personnel search through scans of passenger baggage at the airport.

You've just watched JoVE's introduction on conducting a visual search experiment. Now you should have a good understanding of how to make visual search stimuli for two different types of visual search conditions, how to conduct the experiment, and finally how to analyze and interpret the results.

You should also have an idea about the type of attention that is required when you are looking for keys on a messy desk or finding the ripest-looking fruit at the grocery store.

Thanks for watching!