このコンテンツを視聴するには、JoVE 購読が必要です。 サインイン又は無料トライアルを申し込む。

Method Article

合成核メルトガラスの製造

要約

A protocol for the production of synthetic nuclear melt glass, similar to trinitite, is presented.

要約

Realistic surrogate nuclear debris is needed within the nuclear forensics community to test and validate post-detonation analysis techniques. Here we outline a novel process for producing bulk surface debris using a high temperature furnace. The material developed in this study is physically and chemically similar to trinitite (the melt glass produced by the first nuclear test). This synthetic nuclear melt glass is assumed to be similar to the vitrified material produced near the epicenter (ground zero) of any surface nuclear detonation in a desert environment. The process outlined here can be applied to produce other types of nuclear melt glass including that likely to be formed in an urban environment. This can be accomplished by simply modifying the precursor matrix to which this production process is applied. The melt glass produced in this study has been analyzed and compared to trinitite, revealing a comparable crystalline morphology, physical structure, void fraction, and chemical composition.

概要

Concerns over the potential malicious use of nuclear weapons by terrorists or rogue nations have highlighted the importance of nuclear forensics analysis for the purpose of attribution.1 Rapid post-detonation analysis techniques are desirable to shorten the attribution timeline as much as possible. The development and validation of such techniques requires realistic nuclear debris samples for testing. Nuclear testing no longer occurs in the United States and nuclear surface debris from the testing era is not readily available (with the exception of trinitite - the melt glass produced by the first nuclear test at the trinity site) and therefore realistic surrogate debris is needed.

The primary goal of the method described here is the production of realistic surrogate nuclear debris similar to trinitite. Synthetic nuclear melt glass samples which are readily available to the academic community can be used to test existing analysis techniques and to develop new methods such as thermo-chromatography for rapid post-detonation analysis.2 With this goal in mind the current study is focused on producing samples which mimic trinitite but do not contain any sensitive weapon design information. The fuel and tamper components within these samples are completely generic and the comparison to trinitite is based on chemistry, morphology, and physical characteristics. The similarities between trinitite and the synthetic nuclear melt glass produced in this study have been previously discussed.3

The purpose of this article is to outline the details of the production process used at the University of Tennessee (UT). This production process was developed with two key parameters in mind: 1) the composition of material incorporated into nuclear melt glass, and 2) the melting temperature of the material. Methods exist for estimating the melting temperature of glass forming networks4 and these techniques have been employed here, along with additional experimentation to determine the optimal processing temperature for the trinitite matrix.5

Alternative methods for surrogate debris production have been published recently. The use of high power lasers has the advantage of creating sufficiently high temperatures to cause elemental fractionation within the target matrix.6 Porous chromatographic substrates have been used to produce small particles similar to fallout particles using condensed phase methods7. The latter method is most useful for producing particulate debris (nuclear fallout) and has been demonstrated with natural metals. The advantages of the method presented here are 1) simplicity, 2) reproducibility, and 3) scalability (sample sizes can range from tiny beads to large chunks of melt glass). Also, this method is expandable both in terms of production output and variety of explosive scenarios covered, and it has already been demonstrated using radioactive materials. A sample has been successfully activated at the High Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) at Oak Ridge National Laboratory (ORNL). Natural uranium compounds were added to the matrix prior to melting and fission products were produced in situ by neutron irradiation.

Methods within the glass making industry and those employed for the purpose of radioactive waste immobilization8 have been consulted in the development of the method presented here. The unique effects of radiation in glasses are of inherent interest9 and will constitute an important area of study as this method is further developed.

The method described below is appropriate for any application where a bulk melt glass sample is desired. These samples most closely resemble the material found near the epicenter of a nuclear explosion. Samples of various sizes can be produced, however, methods employing plasma torches or lasers will be more useful for simulating fine particulate debris. Also, commercial HTFs do not reach temperatures high enough to cause elemental fractionation for a wide range of elements. This method should be employed when physical and morphological characteristics are of primary importance.

プロトコル

注意:ここで説明するプロセスは、放射性物質の使用(例えば、ウラン六水和物)と、いくつかの腐食性物質を含んでいます。適切な防護服や機器は、サンプル調製中(白衣、手袋、眼の保護、およびヒュームフードを含む)を使用する必要があります。また、この作業に使用実験室面積は放射能汚染のために定期的に監視する必要があります。

注:必要に応じて化学化合物を 、表1に記載されているこの製剤は、先に検討することによって開発されたトリニタイトための組成データを報告し、ここで報告された10質量分率は、いくつかの異なるトリニタイトサンプルの質量分率を平均することによって決定された10 "欠落"塊。 (画分が1に合計しないように)燃料、タンパーを追加する際にある程度の柔軟性を可能にするために存在し、他の成分。いくつかのトリニタイトサンプルの我々の独立した分析は、石英のみ鉱物相であることを示唆していますトリニタイトで生存する。5そこで、石英は、当社の標準トリニタイト製剤(STF)に含まれる唯一の鉱物です。他の鉱物の遺物粒がトリニタイトで報告されているが、11これらは例外ではなく、ルールになる傾向があります。一般的には、石英、溶融ガラスに見られる唯一の鉱物である。10,12また、石英砂は、都市核溶融ガラスの形成に重要となるアスファルトやコンクリートの一般的な構成要素です。

-4| 平均化トリニタイトデータ | 標準トリニタイト製剤(STF) | ||

| 化合物 | 質量分率 | 化合物 | 質量分率 |

| SiO 2 | 6.42x10 -1 | SiO 2 | 6.42x10 -1 |

| Al 2 O 3 | 1.43x10 -1 | Al 2 O 3 | 1.43x10 -1 |

| CaO | 9.64x10 -2 | CaO | 9.64x10 -2 |

| FeO | 1.97x10 -2 | 1.97x10 -2 | |

| MgOの | 1.15x10 -2 | MgOの | 1.15x10 -2 |

| Na 2 Oを | 1.25x10 -2 | Na 2 Oを | 1.25x10 -2 |

| K 2 O | 5.13x10 -2 | KOH | 6.12x10 -2 |

| MnO | 5.05x10 -4 | MnO | |

| TiO 2の | 4.27x10 -3 | TiO 2の | 4.27x10 -3 |

| トータル | 9.81x10 -1 | トータル | 9.91x10 -1 |

化合物の表1。リスト。

STFの調製

注意:必要な機器は、マイクロバランス、金属ヘラ、セラミック乳鉢と乳棒、化学ヒュームフード、ゴム手袋、白衣、および眼の保護が含まれています。

- 非放射性成分の混合

- 石英砂の少なくとも65グラム(SiO 2)ではAl 2 O 3を15gを取得</サブ>粉末、酸化カルシウム粉末10g、のFeO粉末2g、MgO粉末2gを、Na 2 Oを粉末2g、KOHペレット7gの、酸化マンガン粉末1g及びTiO 2粉末1g( 表1に列挙した化合物)。

- 表1に記載されているように正確に、各化合物の質量分率を測定するために、微量天秤と小さなへらを使用してください。最良の結果を一度に非放射性前駆体マトリックスの100グラムを準備するために。

- (〜10〜20ミクロンのサイズの顆粒に)粉砕する乳鉢と乳棒を使用して、徹底的に化合物を混合し、SiO 2を64.2グラムを含む均質な粉末混合物を形成する、 の Al 2 O 3、CaOを、1.97グラムの9.64グラムの14.2グラムFeO、MgOを1.15グラム、のNa 2 Oを 1.25グラムのKOHの6.12グラム、のMnOの0.0505グラム、及びTiO 2の0.427グラム。

- 次のステップが取られる直前に、ボールミキサーを使用して、混合物を撹拌します。

- ウラン六水和物(UNH)とSTFの混合

- AcquUNHの少なくとも1gをIRE。

- ヒュームフードの内側には、1〜2μmで顆粒の微粉末を形成する(乳鉢と乳棒を使用して)いくつかのUNH結晶を粉砕。

- (この比率は1キロトンの収率で単純な武器をシミュレートするために適切である)非放射性前駆体マトリックスのグラム当たりUNHの33.75μgのを追加します。13

- 乳鉢と乳棒を用いて、UNH含む、粉末混合物を混ぜます。溶融工程の直前に最終混合を完了します。

1グラムメルトガラスサンプルの2生産

注意:必要な機器は、1,600℃以上、高純度黒鉛ルツボ、長いステンレス製るつぼトング、耐熱手袋、眼の保護定格HTFが含まれています。炉からサンプルを導入するか、削除する際に耐熱手袋と目の保護を着用してください。彼らは炉からのまぶしさを軽減としてティント安全ゴーグル(または太陽メガネ)が便利です。

- 非放射性サンプルの製造

- 純粋な石英砂の〜100gで(例えばモルタルなど)の厚さのセラミックの皿を記入し、試料が溶融される炉の場所の近くに、室温で維持します。

- 1,500℃に予熱HTF。

- 慎重に非放射性粉末混合物の1.00グラムを測定し、高純度の黒鉛坩堝に粉末を配置します。

- 慎重に(鋼るつぼトングの長い対を用いて)加熱HTFでるつぼを配置し、30分間混合物を溶融します。

- (再びトングを使用して)サンプルを削除し、砂を充填したモルタルへの溶融サンプルを注ぎます。

- ガラスビーズを取り扱う前に1〜2分間冷却してください。

- (必要な場合)の残留砂を除去するために、ビーズを磨きます。

- 放射性試料の作製

- 繰り返しは、上記の2.1.1と2.1.2手順。

- 慎重に(UNH含む)放射性粉末混合物の1.00グラムを測定し、powdを配置相互汚染を避けるために、別個のへらと天秤を用いて高純度黒鉛坩堝におけるER。

- 上記2.1.6 - を繰り返し2.1.4手順。

- 放射能汚染をチェックする(手持ち放射線検出器および/またはスワイプアッセイを用いて)炉の周囲の領域を監視します。

3.サンプルのアクティベーション

注:下記の式は、兵器級(濃縮)ウラン金属の使用を想定して誘導しました。 UNHまたは酸化ウランの量は、元素のウランの質量分率と235 U濃縮のレベルに応じてスケーリングする必要があります。

- ウラン笛でメルトガラス試料の活性化

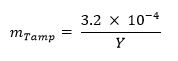

- (mは Uウラン質量分率を表し、Yは、武器の収率を示す)13以下の式を使用して、サンプルに必要なウラン金属の質量分率を計算します。

473 / 53473eq1.jpg "/> - オプション:以下の式を使用して、タンパ(例えば、天然ウラン、鉛、タングステン)の質量分率を計算します。13

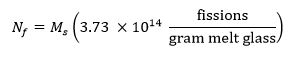

- M sはグラムでのサンプルの質量を表し、N fは照射の間、サンプルにおいて生成さ核分裂の数を表し、以下の式13を用いて試料中の核分裂の目標数を計算します。

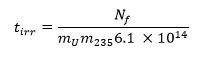

- M 235が 235 Uの質量分率(濃縮レベル)を表し、Tの IRRは、秒単位の照射時間である13以下の式を使用して、必要な照射時間を計算します。

- 以下のためのサンプルを照射4.0×10 14 N / cmで2 /秒の熱中性子束にIRR秒のt。例えば、(35の共振比が熱を持つ)HFIRで気送管1(PT-1)で60秒照射はUNHの870μgの410μgのに(等価を含む試料では約1.1×10 11核分裂が生成されます天然ウラン、または235 Uの3.0μgの)。これは、0.1キロトンの収率で武器によって生成溶融ガラスサンプルをシミュレートするように設計された1つ0.433グラムのガラスビーズのために達成されています。この試料を十分にクックらによって分析された。14

- 放射性試料照射後の処理に適用される安全なプロトコルに従ってください。

- (mは Uウラン質量分率を表し、Yは、武器の収率を示す)13以下の式を使用して、サンプルに必要なウラン金属の質量分率を計算します。

- プルトニウム燃料(計画要因)とメルトガラス試料の活性化

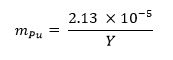

- 13 ここで、m プルトニウム represen以下の式を使用して、サンプルに必要なプルトニウム金属の質量分率を計算しますプルトニウム質量分率TS と Y は、武器の収量を表しています。

- 手順を繰り返し上記の3.1.2と3.1.3。

- 溶融ガラス試料中の核分裂の所望の数を得るために必要な照射時間を決定します。この時間は、組成やグレードプルトニウムだけでなく、中性子エネルギースペクトルに依存します。

- 13 ここで、m プルトニウム represen以下の式を使用して、サンプルに必要なプルトニウム金属の質量分率を計算しますプルトニウム質量分率TS と Y は、武器の収量を表しています。

注意:必要とされるプルトニウム、追加の分析を扱うときに細心の注意を払うべきです。この記事の執筆時点では、唯一のウランは、合成溶融ガラス試料UTで生産し、HFIRで照射に使用されています。

結果

本研究で生産非放射性サンプルはトリニタイトに比べて1〜3は、物理的特性および形態が実際に類似していることを示しますされている。 図1は、巨視的レベルで観察された色と質感の類似性を明らかに写真を提供します。 図2は、ミクロンレベルでの類似の特徴を明らかに走査型電子顕微鏡(SEM)二次電子(SE)画像を示します。 SEM分析は?...

ディスカッション

ステップ1.2.2と1.2.3に関する注意:UNHの正確な量は、シミュレートされるシナリオによって異なります。 Giminaro らによって開発された計画の式は、このペーパーの「サンプル活性化」の項で説明したように、与えられたサンプル13のためのウランの適切な量を選択するために使用することができます。また、酸化ウラン(UO 2またはU 3 O 8)が利用可能な?...

開示事項

This work was performed under grant number DE-NA0001983 from the Stewardship Science Academic Alliances (SSAA) Program of the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA).

謝辞

Portions of this study have been previously published in the Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry.3,13 A patent is pending for this method.

資料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| High Temperature Furnace (HTF) | Carbolite | HTF 18 | 1,800 °C HTF used to melt samples |

| High Temperature Drop Furnace | CM Inc. | 1706 BL | 1,700 °C Drop Furnace used to melt samples |

| Graphite Crucibles | SCP Science | 040-060-041 | 27 ml high purity graphite crucibles (10 pack) |

| Crucible Tongs | Grainger | 5ZPV0 | 26 in., stainless steele tongs for handling crucibles |

| Heat Resistent Gloves | Grainger | 8814-09 | Gloves used to protect hands from heat during sample intro/removal |

| Mortar & Pestle | Fisherbrand | S337631 | 300 ml, Ceramic mortar and pestle for powdering and mixing |

| Micro Balance | Grainger | 8NJG2 | 220 g Cap, high precision scale for measuring powder mass |

| Spatulas | Fisherbrand | 14374 | Metal spatulas for measure small quantities of powder |

| SiO2 | Sigma-Aldrich | 274739-5KG | Quartz Sand CAS Number: 14808-60-7 |

| Al2O3 | Sigma-Aldrich | 11028-1KG | Aluminum Oxide Powder CAS Number: 1344-28-1 |

| CaO | Sigma-Aldrich | 12047-2.5KG | Calcium Oxide Powder CAS Number: 1305-78-8 |

| FeO | Sigma-Aldrich | 400866-25G | Iron Oxide Powder CAS Number: 1345-25-1 |

| MgO | Sigma-Aldrich | 342793-250G | Magnesium Oxide Powder CAS Number: 1309-48-4 |

| Na2O | Sigma-Aldrich | 36712-25G | Sodium Oxide Powder CAS Number: 1313-59-3 |

| KOH | Sigma-Aldrich | 278904-250G | Potasium Hydroxide Pellets CAS Number: 12030-88-5 |

| MnO | Sigma-Aldrich | 377201-500G | Manganese Oxide Powder CAS Number: 1344-43-0 |

| TiO2 | Sigma-Aldrich | 791326-5G | Titanium Oxide Beads CAS Number: 12188-41-9 |

参考文献

- Carnesdale, A. . Nuclear Forensics: A Capability at Risk (Abbreviated Version). , (2010).

- Garrison, J. R., Hanson, D. E., Hall, H. L. Monte Carlo analysis of thermochromatography as a fast separation method for nuclear forensics. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 291 (3), 885-894 (2011).

- Molgaard, J. J., et al. Development of synthetic nuclear melt glass for forensic analysis. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 304 (3), 1293-1301 (2015).

- Fluegel, A. Modeling of Glass Liquidus Temperatures using Disconnected Peak Functions. , (2007).

- Oldham, C. J., Molgaard, J. J., Auxier, J. D., Hall, H. L. Comparison of Nuclear Debris Surrogates Using Powder X-Ray Diffraction. , (2014).

- Liezers, M., Fahey, A. J., Carman, A. J., Eiden, G. C. The formation of trinitite-like surrogate nuclear explosion debris ( SNED ) and extreme thermal fractionation of SRM-612 glass induced by high power CW CO 2 laser irradiation. J Radional Nucl Chem. 304 (2), 705-715 (2015).

- Harvey, S. D., et al. Porous chromatographic materials as substrates for preparing synthetic nuclear explosion debris particles. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 298 (3), 1885-1898 (2013).

- Hanni, J. B., et al. Liquidus temperature measurements for modeling oxide glass systems relevant to nuclear waste vitrification. J Mater Res. 20 (12), 3346-3357 (2005).

- Weber, W. J., et al. Radiation Effects in Glasses Used for Immobilization of High-Level Waste and Plutonium Disposition. J Mater Res. 12 (8), 1946-1978 (1997).

- Eby, N., Hermes, R., Charnley, N., Smoliga, J. A. Trinitite-the atomic rock. Geol Today. 26 (5), 180-185 (2010).

- Bellucci, J. J., Simonetti, A. Nuclear forensics: searching for nuclear device debris in trinitite-hosted inclusions. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 293 (1), 313-319 (2012).

- Ross, C. S. . Optical Properties of Glass from Alamogordo, New Mexico. , (1948).

- Giminaro, A. V., et al. Compositional planning for development of synthetic urban nuclear melt glass. J Radional Nucl Chem. , (2015).

- Cook, M. T., Auxier, J. D., Giminaro, A. V., Molgaard, J. J., Knowles, J. R., Hall, H. L. A comparison of gamma spectra from trinitite versus irradiated synthetic nuclear melt glass. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. , (2015).

- Fahey, J., Zeissler, C. J., Newbury, D. E., Davis, J., Lindstrom, R. M. Postdetonation nuclear debris for attribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 107 (47), 20207-20212 (2010).

- Bellucci, J. J., Simonetti, A., Koeman, E. C., Wallace, C., Burns, P. C. A detailed geochemical investigation of post-nuclear detonation trinitite glass at high spatial resolution: Delineating anthropogenic vs. natural components. Chem Geol. 365, 69-86 (2014).

- Donohue, P. H., Simonetti, A., Koeman, E. C., Mana, S., Peter, C. Nuclear Forensic Applications Involving High Spatial Resolution Analysis of Trinitite Cross-Sections. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. , (2015).

- Eaton, G. F., Smith, D. K. Aged nuclear explosive melt glass: Radiography and scanning electron microscope analyses documenting radionuclide distribution and glass alteration. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 248 (3), 543-547 (2001).

- Kersting, A. B., Smith, D. K. . Observations of Nuclear Explosive Melt Glass Textures and Surface Areas. , (2006).

- . . IAEA Safeguards Glossary. , (2001).

- Glasstone, S., Dolan, P. . Effects of Nuclear Weapons. , (1977).

- Carney, K. P., Finck, M. R., McGrath, C. A., Martin, L. R., Lewis, R. R. The development of radioactive glass surrogates for fallout debris. J Radioanal Nucl Chem. 299 (1), 363-372 (2013).

- Molgaard, J. J., Auxier, J. D., Hall, H. L. A Comparison of Activation Products in Different Types of Urban Nuclear Melt Glass. , (2015).

転載および許可

このJoVE論文のテキスト又は図を再利用するための許可を申請します

許可を申請さらに記事を探す

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2023 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved