Method Article

Non-chromatographic Purification of Recombinant Elastin-like Polypeptides and their Fusions with Peptides and Proteins from Escherichia coli

* Wspomniani autorzy wnieśli do projektu równy wkład.

W tym Artykule

Podsumowanie

Elastin-like polypeptides are stimulus-responsive biopolymers with applications ranging from recombinant protein purification to drug delivery. This protocol describes the purification and characterization of elastin-like polypeptides and their peptide or protein fusions from Escherichia coli using their lower critical solution temperature phase transition behavior as a simple alternative to chromatography.

Streszczenie

Elastin-like polypeptides are repetitive biopolymers that exhibit a lower critical solution temperature phase transition behavior, existing as soluble unimers below a characteristic transition temperature and aggregating into micron-scale coacervates above their transition temperature. The design of elastin-like polypeptides at the genetic level permits precise control of their sequence and length, which dictates their thermal properties. Elastin-like polypeptides are used in a variety of applications including biosensing, tissue engineering, and drug delivery, where the transition temperature and biopolymer architecture of the ELP can be tuned for the specific application of interest. Furthermore, the lower critical solution temperature phase transition behavior of elastin-like polypeptides allows their purification by their thermal response, such that their selective coacervation and resolubilization allows the removal of both soluble and insoluble contaminants following expression in Escherichia coli. This approach can be used for the purification of elastin-like polypeptides alone or as a purification tool for peptide or protein fusions where recombinant peptides or proteins genetically appended to elastin-like polypeptide tags can be purified without chromatography. This protocol describes the purification of elastin-like polypeptides and their peptide or protein fusions and discusses basic characterization techniques to assess the thermal behavior of pure elastin-like polypeptide products.

Wprowadzenie

Elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) are biopolymers composed of the repeating pentapeptide VPGXG where X, the guest residue, is any amino acid except proline. ELPs exhibit lower critical solution temperature (LCST) phase transition behavior, such that a homogeneous ELP solution will separate into two phases upon heating to its LCST, which is commonly called the inverse transition temperature (Tt) in the ELP literature1. The two phases are composed of a very dilute ELP globule phase and an ELP rich sediment phase. The ELP rich sediment is formed on a short timescale upon aggregation of the ELP chains into micron-sized particles that subsequently coalesce. This behavior occurs over a range of a few degrees Celsius and is typically reversible, as a homogeneous solution is recovered upon returning to a temperature below the Tt.

ELPs are typically synthesized in Escherichia coli (E. coli) from an artificial gene that is ligated into an expression plasmid. This plasmid is then transformed into an E. coli cell line that is optimal for protein expression. We have exclusively used the T7-lac pET vector system for expression of a large variety of ELPs in E. coli, although other expression systems in yeast2-4, fungi5, and plants6-8 have also been utilized by other investigators. A number of approaches exist to genetically construct repetitive ELP genes, including recursive directional ligation (RDL)9, recursive directional ligation by plasmid reconstruction (PRe-RDL)10, and overlap extension rolling circle amplification (OERCA)11. The ability to engineer ELPs at the genetic level affords the opportunity to use recombinant DNA techniques to create ELPs with a variety of architectures (e.g., monoblocks, diblocks, triblocks, etc.), which can be further appended with functional peptides and proteins. Control at the genetic level also ensures that each ELP is expressed with the exact length and composition dictated by its genetic plasmid template, providing perfectly monodisperse biopolymer products.

The thermal properties of each ELP depend on parameters intrinsic to the biopolymer such as its molecular weight (MW) and sequence, as well as extrinsic factors including its concentration in solution and the presence of other cosolutes, such as salts. The length of the ELP12 and its guest residue composition1,13,14 are two orthogonal parameters in ELP design that can be used to control the Tt, where hydrophobic guest residues and longer chain lengths result in lower Tts, while hydrophilic guest residues and shorter chain lengths result in higher Tts. ELP concentration is inversely related to the Tt, where solutions of greater ELP concentration have lower Tts12. The type and concentration of salts also influence the ELP Tt, where the effect of salts follows the Hofmeister series15. Kosmotropic anions (Cl- and higher on the Hofmeister series) lower the ELP Tt and increasing salt concentration enhances this effect. These intrinsic and extrinsic parameters can be tuned to obtain thermal behavior within a target temperature range that is required for a specific application of an ELP.

The stimulus-responsive behavior of ELPs is useful for a diverse range of applications including biosensing16,17, tissue engineering18, and drug delivery19,20. Additionally, when ELPs are fused to peptides or proteins at the genetic level, the ELP can serve as a simple purification tag to provide an inexpensive batch method for purification of recombinant peptides or proteins that requires no chromatography21. Modification of the purification process ensures that the activity of the peptide or protein fused to the ELP is maintained. Peptide or protein ELP fusions can be purified for applications in which the ELP tag is useful22,23 or alternatively, when the free peptide or protein is required, a protease recognition site can be inserted between the peptide or protein and ELP. Removal of the ELP tag can then be achieved by digestion with free protease or a protease ELP fusion, where the latter provides the additional ease of processing as a final round of ELP purification can separate the ELP tag and protease ELP fusion from the target peptide or protein in a single step24,25. The following protocol describes the purification procedure for ELPs and peptide or protein ELP fusions by means of their thermal properties and discusses basic techniques for characterizing the thermal response of ELP products.

Protokół

1. ELP Expression

- Inoculate 3 ml of sterile Terrific Broth media with a DMSO stock or agar plate colony of E. coli suitable for protein expression that contains the desired ELP-encoding plasmid under control of the T7-lac promoter. Add the appropriate antibiotic and incubate at 37 °C overnight (O/N) with continuous shaking at 200 rpm.

- Add 1 ml of the O/N culture to 1 L of Terrific Broth sterile media in a 4-L flask. Add the appropriate antibiotic and incubate at 37 °C for 24 hr with continuous shaking at 200 rpm. NOTE: The “leaky” baseline expression seen with the T7-lac promoter is sufficient for high level expression of many ELPs if the culture is incubated for 24 hr. However, a more conventional approach can be used, wherein protein expression is further induced by the addition of 0.2-1 mM isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) when the optical density of the culture reaches 0.6.

- Transfer the culture from the 4-L flask to a 1-L centrifuge bottle and centrifuge at 4 °C for 15 min at 2,000 x g.

- Discard the supernatant. NOTE: If more than 1 L of culture is grown they can be condensed by adding another liter of culture to the pellet and repeating step 1.3. Up to 2 L of culture can be condensed into a single cell pellet.

- Resuspend the pellet in phosphate buffered saline (PBS), water, or other desired buffer to reach 45 ml of cell suspension and transfer to a 50 ml conical tube.

2. ELP Purification: Preliminary Steps and First Round of Inverse Transition Cycling

- Sonicate the resuspended cell pellet for a total of 9 min in cycles of 10 sec ‘on’ and 20 sec ‘off’ at an output power of 85 W, while keeping the sample on ice. Briefly allow the sample to cool on ice and then repeat the 9 min cycle once more. NOTE: If the ELP is anticipated to have a very low Tt the ‘off’ interval can be increased up to 40 sec to avoid heating of the solution above the Tt.

- Transfer the lysate to a 50 ml round bottom centrifuge tube.

- Add 2 ml of 10% (w/v) polyethyleneimine (PEI) for each liter of culture and shake to mix. NOTE: PEI is a positively charged polymer that aids in the condensation of negatively charged genetic contaminants. Do not perform this step if the ELP is negatively charged, as the PEI may also condense and remove the ELP product.

- Centrifuge at 4 °C for 10 min at 16,000 x g.

- Transfer the supernatant to a clean 50 ml round bottom centrifuge tube and discard the pellet.

- Optional “bake out” step: Incubate the sample at 60 °C for 10 min to denature protein contaminants and then transfer to 4 °C or to ice until the ELP is completely resolubilized. Centrifuge the sample at 4 °C for 10 min at 16,000 x g. Transfer the supernatant to a clean 50 ml round bottom centrifuge tube and discard the pellet. NOTE: Do not perform this step if a peptide or protein is fused to the ELP and is expected to denature in the condition of elevated heat. This may cause the ELP transition to become heat-irreversible or may destroy the activity of the fused moiety.

- Induce the ELP transition with the addition of crystalline NaCl (not exceeding 3 M). Alternatively, sodium citrate (not exceeding 0.3 M) can be used for ELPs that have higher Tts or low yields. NOTE: The solution should turn cloudy once the salt has dissolved, indicating the phase separation of ELP from solution. Very hydrophilic ELPs with high Tts may require some degree of heating, in combination with the addition of salt, to induce the phase separation of the ELP in this preliminary induction of the ELP transition.

- Centrifuge at room temperatue (RT) for 10 min at 16,000 x g (hot spin). NOTE: An ELP pellet should be observed, whose size depends on the expression yield of the ELP. This ELP pellet may at first appear opaque, but after cooling it will appear translucent and may be brown in color. The ELP pellet will become more colorless as purification proceeds and contaminants are removed.

- Discard the supernatant and add 1-5 ml of desired buffer to the pellet. Resuspend the pellet by pipetting or setting the tube to rotate at 4 °C. NOTE: The required volume of buffer will depend on the size of the ELP pellet, and thus the yield of ELP expression, where a sufficient amount of buffer should be added to allow for resolubilization of the ELP pellet. ELPs with high cysteine content benefit from purification in water with 10 mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP-HCl) at pH 7 to eliminate disulfide interactions with contaminating proteins. ELPs with high charge content benefit from purification at a pH adjusted to neutralize their charge and reduce electrostatic interactions with contaminating proteins.

- Transfer the resuspended ELP solution in 1 ml aliquots into clean 1.5-ml microcentrifuge tubes.

- Centrifuge at 4 °C for 10 min at 16,000 x g (cold spin). A small pellet of insoluble contaminants should be observed.

- Transfer the supernatant to a clean tube and discard the pellet.

3. ELP Purification: Subsequent Rounds of Inverse Transition Cycling

- Induce the ELP transition with heat and/or the addition of NaCl. Samples can be incubated on a heat block or in a water bath for 15 min at a temperature above the Tt. If, however, the ELP is fused to a protein (precluding the use of heat) or if the ELP has a high Tt that cannot be reached with heat alone, a 5 M solution of NaCl can be added drop-wise to induce the ELP transition. NOTE: The solution should turn cloudy, indicating the phase separation of ELP from solution.

- Centrifuge for 10 min at 16,000 x g (hot spin). If heat was used in step 3.1, perform this centrifugation step at a temperature above that which was required to induce the ELP transition. If NaCl alone was used in step 3.1, perform this centrifugation step at RT. NOTE: An ELP pellet should be observed.

- Discard the supernatant, add 500-750 μl of desired buffer, and resuspend the pellet by pipetting or setting the tube to rotate at 4 °C.

- Centrifuge at 4 °C for 10 min at 16,000 x g (cold spin). A small pellet of insoluble contaminants should be observed.

- Transfer the supernatant to a clean tube and discard the pellet.

- Repeat steps 3.1 to 3.5 until no contaminant pellet is observed during step 3.4.

4. Post-purification Processing (optional)

- If desired, dialyze the sample against a suitable buffer to remove excess salt from the purified ELP solution. NOTE: ELPs to be lyophilized should be dialyzed against ddH2O O/N at 4 °C.

- If desired, lyophilize the ELP for long-term storage by freezing the solution at -80 °C for 30 min prior to lyophilizing O/N. NOTE: Lyophilization should not be used for ELPs with appended proteins.

- If desired, recover free peptide or protein from a peptide or protein ELP fusion by removing the ELP tag:

- Digest the peptide or protein ELP fusion with biotinylated protease (as recommended by the protease supplier) or with a protease ELP fusion corresponding to the protease site genetically designed between the peptide or protein and ELP.

- If applicable, remove the biotinylated protease using streptavidin-modified beads (as recommended by the protease supplier).

- Induce the transition of the cleaved ELP and/or protease ELP fusion by the drop-wise addition of a 5 M NaCl solution.

- Centrifuge at RT for 10 min at 16,000 x g. NOTE: An ELP pellet should be observed.

- Collect the supernatant and discard the ELP pellet. Dialyze the supernatant against a desired buffer or use a centrifugal filter to perform a buffer exchange in order to remove the high salt concentration from the pure peptide or protein solution.

- Confirm the complete cleavage of free peptide or protein from the ELP tag by sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE).

5. Characterization: SDS-PAGE

- Prepare ELP samples for SDS-PAGE by mixing 10 μl of ELP diluted in water with 10 μl of sample buffer containing 2-mercaptoethanol. NOTE: 40 μg of ELP is often sufficient to evaluate the size and purity of the ELP product.

- Incubate the sample at 100 °C for 2 min and then load onto a polyacrylamide gel along with an appropriately sized protein ladder.

- Run the gel at 180 V until the dye approaches the bottom of the gel (approximately 45 min).

- Stain the gel with a 0.5 M CuCl2 solution for 5 min, while rocking. NOTE: ELPs are typically not visualized by Coomassie Brilliant Blue stain, as some ELP sequences do not interact with this dye. Coomassie Brilliant Blue interacts primarily with arginine residues and interacts weakly with other basic residues–histidine and lysine–and aromatic residues–tryptophan, tyrosine, and phenylalanine26. Thus ELPs and peptide or protein ELP fusions can be stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue only if their primary sequence includes a sufficient number of these specific residues.

- Verify that the MW of the ELP band corresponds to that of the theoretical MW expected from the ELP gene and that no extraneous contaminant bands are present. NOTE: Some ELPs migrate with an apparent MW up to 20% higher than their expected MW9,27.

6. Characterization: Matrix-assisted Laser Desorption/ionization Time-of-Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS)

- Prepare an ELP solution in 50% aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid to achieve an ELP concentration of approximately 25 μM. NOTE: This solution should be free of salt, so ELP must be dialyzed against H2O following purification.

- Prepare a matrix solution of saturated sinapinic acid in 50% aqueous acetonitrile containing 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid.

- Add 1 μl of the ELP solution to 9 μl of the matrix solution to achieve an ELP concentration of approximately 2.5 pmol/μl. NOTE: This mixture can be further diluted with matrix solution to optimize the MALDI-TOF signal.

- Deposit 1-2 μl of ELP-matrix mixture onto a metal MALDI plate and let the spot dry completely.

- Obtain 5-10 spectra with MALDI-TOF to determine the mass to charge ratio (m/z) of the ELP and infer its measured MW.

7. Characterization: Temperature-programmed Turbidimetry and Dynamic Light Scattering

- Determine the Tt of the ELP by temperature-programmed turbidimetry:

- Prepare a dilution series (e.g., from 5-100 μM) of ELP solutions in the desired buffer.

- Using a temperature-controlled UV-Vis spectrophotometer, measure the optical density (O.D.) at 350 nm over a range of temperatures (e.g., 20-80 °C) at a heating rate of 1 °C/min. NOTE: If no increase in O.D. is seen the Tt may exceed the upper temperature limit of the instrument. The apparent Tt can be decreased by the addition of NaCl. Start at 1 M NaCl and increase in steps of 0.5 M until the ELP transition is detected within a measurable temperature range.

- Verify reversibility of the ELP transition by measuring the decrease in O.D. over the same range of temperature at a cooling rate of 1 °C/min.

- Determine the Tt of the homopolymer ELP by identifying the inflection point of the turbidity profile (O.D. plotted versus temperature). NOTE: This temperature can be easily defined from the derivative of the O.D. curve, where the temperature corresponding to the maximum of the derivative is defined as the Tt. More complex ELP architectures will display more complicated turbidity profiles and should be further analyzed as described in section 7.2.

- Additional characterization of ELPs that display more complex thermal properties (e.g., ELP diblock copolymers that self-assemble into spherical micelles) is achieved by dynamic light scattering (DLS):

- Prepare an ELP solution in the desired buffer and pass the sample through a filter with a 20-450 nm pore size. NOTE: The choice of filter pore size will depend on the presence, size, and stability of any ELP assemblies in solution. The smallest feasible filter pore size is preferred to eliminate contaminants, such as dust, that diminish the quality of DLS measurements. A larger filter pore size should be used when significant resistance is experienced when passing an ELP solution through smaller filter pore sizes.

- Measure the hydrodynamic radius (RH) over a range of temperatures that corresponds to a region of interest identified in the turbidity profile. NOTE: ELP unimers typically have a RH<10 nm, nanoparticle assemblies have a RH~20-100 nm, and aggregates have a RH>500 nm. Each increase in RH should correspond to an increase in O.D. at 350 nm measured by UV-Vis spectrophotometry as a function of temperature, which is proportional to the size of the particle.

Wyniki

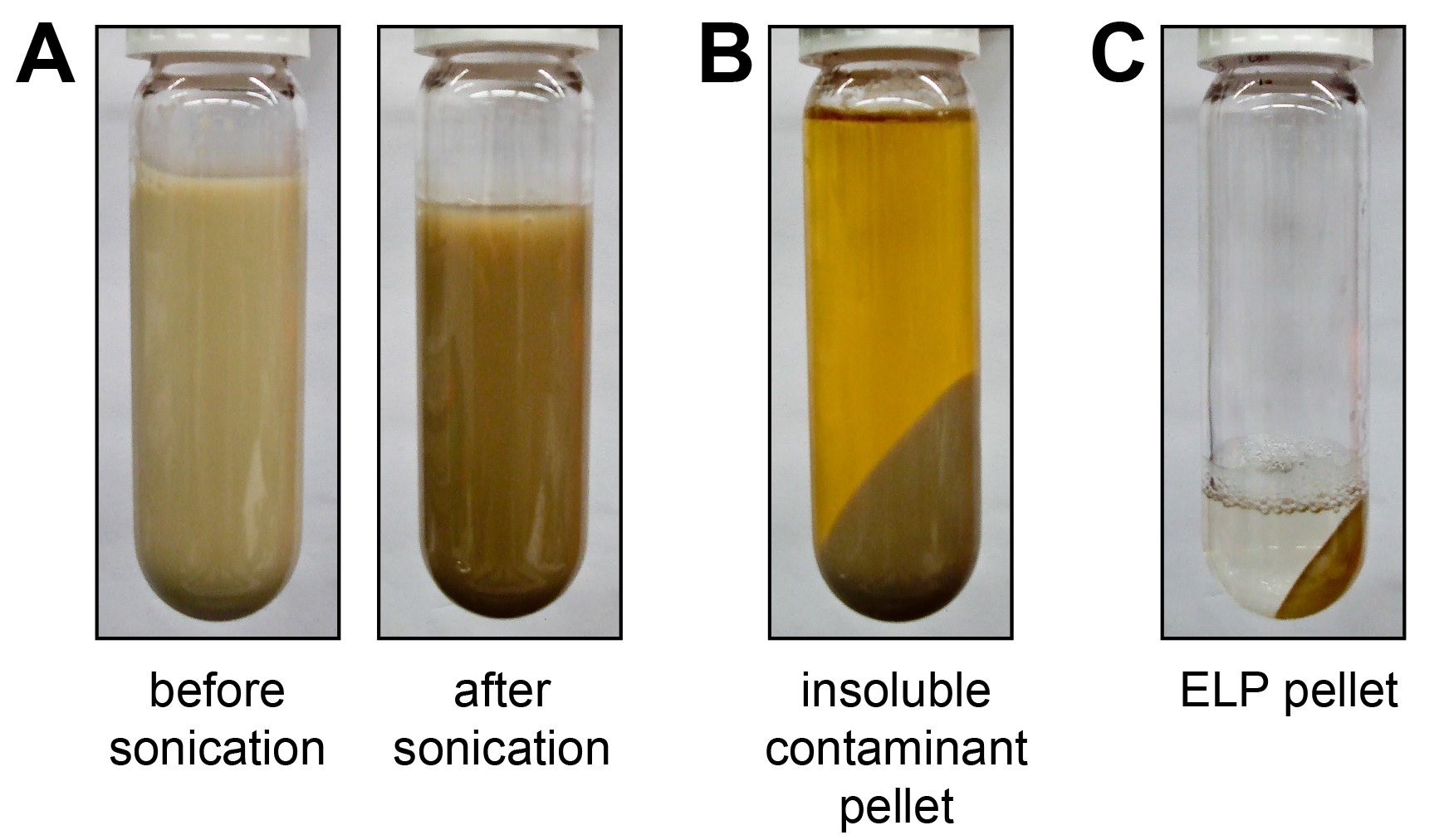

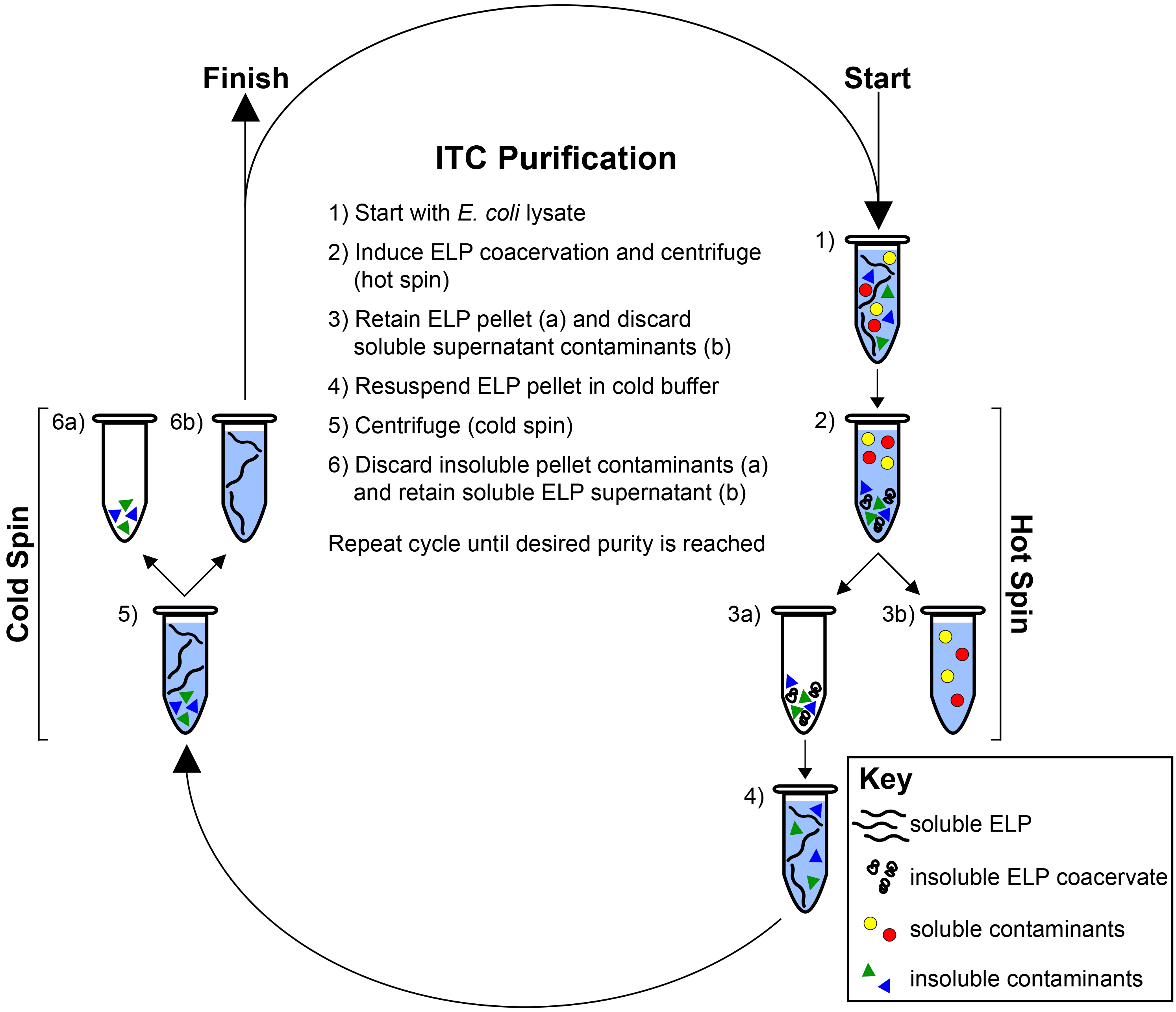

Here we describe representative results for the purification and characterization of an ELP homopolymer and an ELP diblock copolymer. Following 24 hr of expression in E. coli, cells are collected by centrifugation and lysed by sonication. Typically, a subtle change in color occurs after sonication, confirming sufficient cell lysis (Figure 1A). After the addition of PEI, genomic components and cellular debris are collected by centrifugation, separating a large pellet of insoluble contaminants from the soluble ELP in the supernatant (Figure 1B). ELP is further purified by inverse transition cycling (ITC), which exploits the LCST behavior to separate the ELP from both soluble and insoluble contaminants (Figure 2)28. The phase transition of the ELP is triggered by the addition of heat and/or salt. Centrifugation results in the formation of a pellet at the bottom of the tube that consists of ELP and some insoluble contaminants (Figure 1C). This step –termed a hot spin– discards soluble contaminants in the supernatant while the ELP pellet is retained and resuspended in cold buffer. The resolubilized ELP is centrifuged again at 4 °C. This step –termed a cold spin– discards the pellet of insoluble contaminants while the supernatant containing soluble ELP is retained. Repeating the cycle of alternating hot and cold spins increases the purity of the ELP, but at the cost of slightly decreasing yield, as residual ELP is lost during each ITC round in centrifuge tubes and on pipette tips.

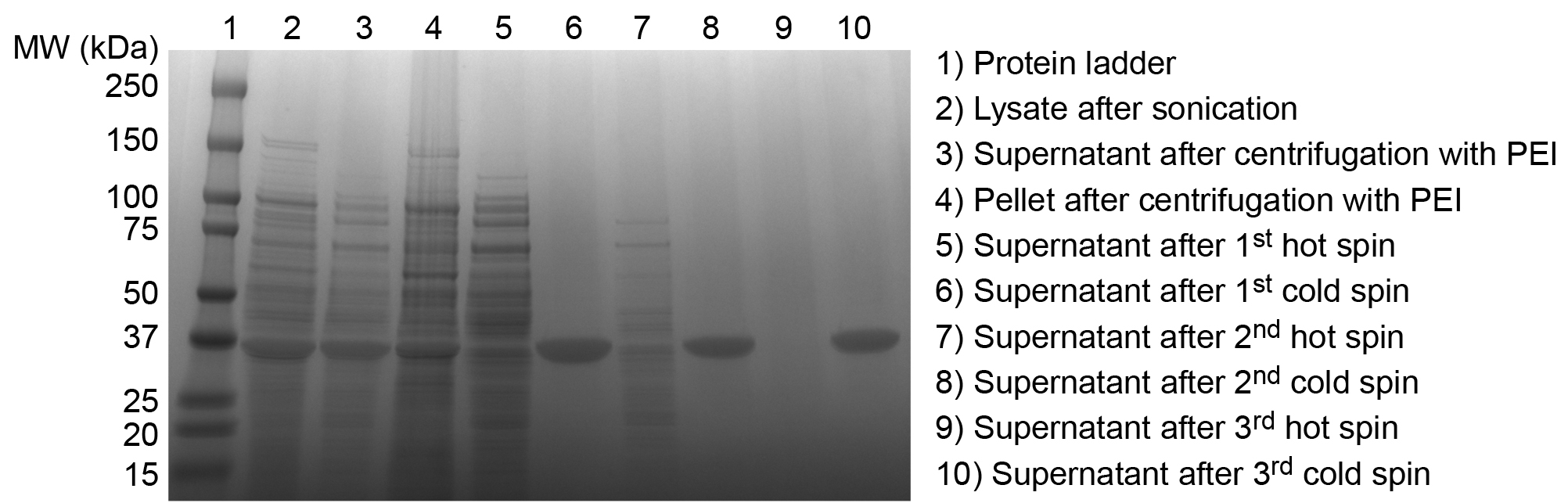

Successful purification of ELPs and peptide or protein ELP fusions is confirmed by SDS-PAGE. Small aliquots taken throughout the purification process demonstrate the progressive purification of ELP from the E. coli lysate. ELP is overexpressed in the crude E. coli lysate and contaminants decrease with successive rounds of ITC (Figure 3). Purified ELP appears as a single band near the predicted theoretical MW.

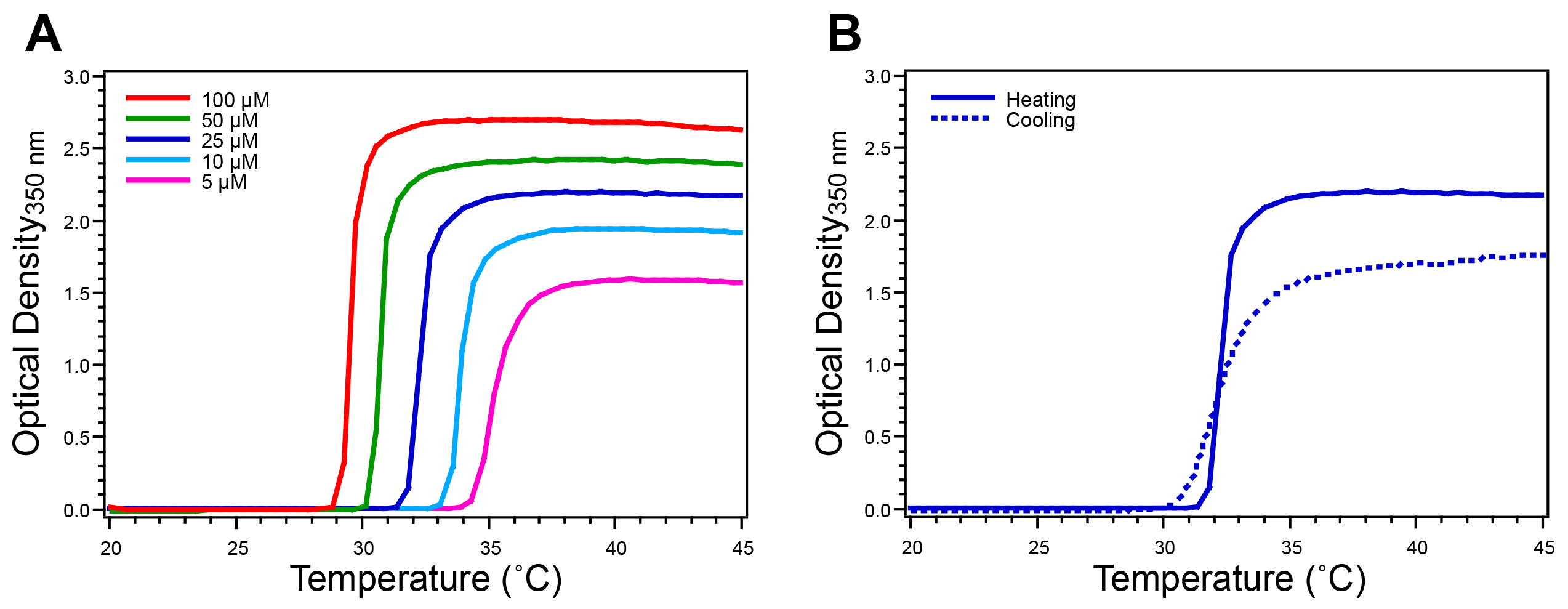

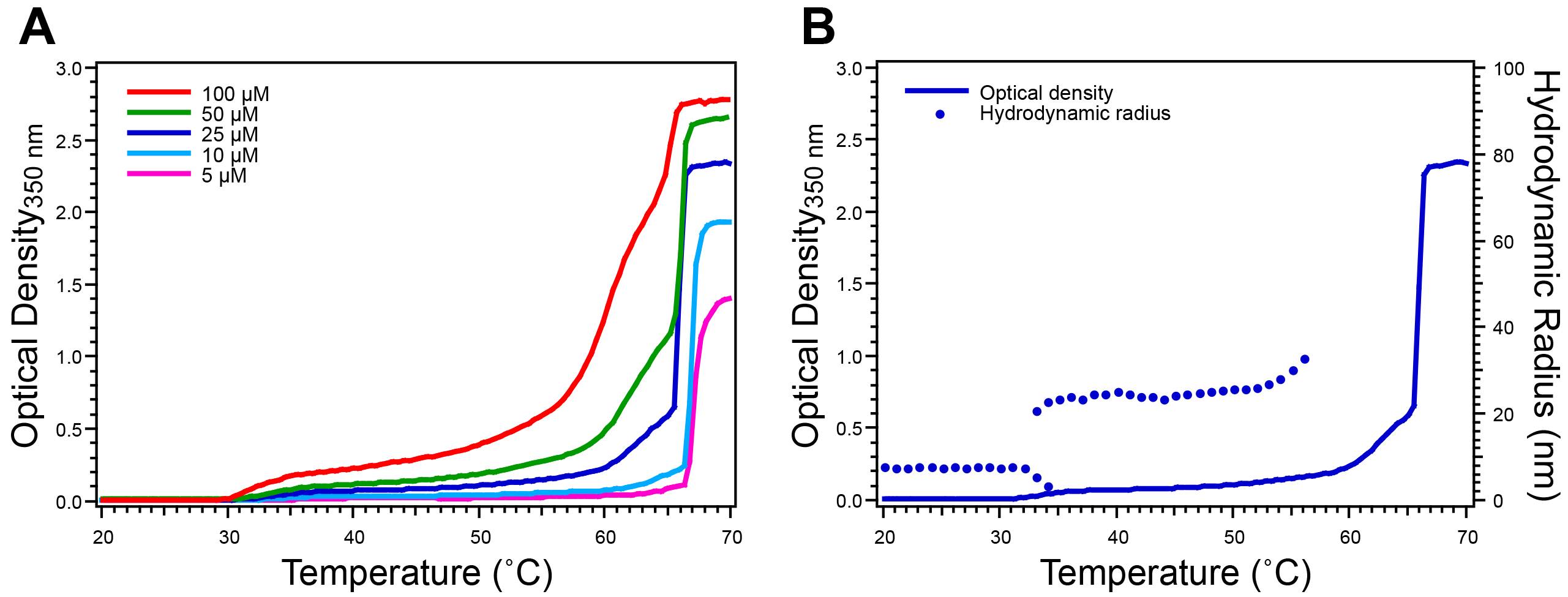

The ELP Tt is characterized by temperature-programmed turbidimetry. The turbidity profile of an ELP homopolymer exhibits a single sharp increase in O.D. at 350 nm (approximately 2.0 units above baseline for an ELP concentration of 25 μM) (Figure 4A). Cooling turbidity scans confirm the reversible nature of the ELP transition as the O.D. returns to baseline when the temperature is lowered below the Tt (Figure 4B). ELP diblock copolymers exhibit a more complex turbidity profile, as compared to homopolymer ELPs. The O.D. typically first increases to 0.1-0.5 units above baseline, after which the O.D. increases sharply to 2.0 units above baseline (Figure 5A). DLS measurements provide information about the change in RH with respect to temperature, corroborating the information gained from the turbidity profile (Figure 5B).

Figure 1. Preliminary ELP purification. After 24 hr of expression, E. coli cells are collected by centrifugation and resuspended in PBS. A) Cells are lysed by sonication, which is accompanied by a subtle change in color such that the lysate darkens after sonication. B) After addition of PEI to condense DNA contaminants, the lysate is centrifuged and a large pellet of insoluble debris is separated from soluble ELP in the supernatant. C) The ELP transition is induced with the addition of heat and/or salt and centrifugation forms a translucent ELP pellet. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2. Inverse transition cycling. ELP is purified by means of its LCST behavior from both soluble and insoluble contaminants. Starting with the ELP-rich lysate (1) the ELP transition is induced with the addition of heat and/or salt and the ELP is separated by centrifugation (hot spin) (2). The ELP pellet is retained (3a) while the supernatant containing soluble contaminants is discarded (3b). The ELP is resuspended in cold buffer (4) and centrifuged again at 4 °C (cold spin) (5). The pellet containing insoluble contaminants is discarded (6a) while the supernatant containing soluble ELP is retained (6b). Cycles of alternating hot and cold spins are repeated until the desired purity is reached, as determined with SDS-PAGE. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3. SDS-PAGE analysis of ELP purification products. Successful purification of an ELP is confirmed by SDS-PAGE. Overexpressed ELP is evident in the crude E. coli lysate after sonication (2). After the addition of PEI and centrifugation the soluble ELP is largely retained in the supernatant (3), although some ELP is lost in the discarded pellet of insoluble contaminants (4). Supernatant following the first hot spin contains significant levels of soluble contaminants (5). Supernatant following the first cold spin indicates good separation of ELP from insoluble contaminants (6). Additional cycles of hot (7) and cold spins (8) remove residual soluble and insoluble contaminants, respectively, until final hot (9) and cold spin (10) supernatants exhibit no extraneous contaminant bands, confirming satisfactory purity of the ELP product. This ELP homopolymer, with a sequence of SKGPG-(VGVPG)80-Y, has an expected molecular weight of 33.37 kDa. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4. Characterization of ELP homopolymer by temperature-programmed turbidimetry. The ELP Tt is determined by monitoring the O.D. at 350 nm while increasing the temperature at a rate of 1 °C/min. A) ELP homopolymers exhibit a single sharp increase in O.D. that defines their Tt at a given concentration. B) The reversibility of the ELP transition is verified by monitoring the O.D. at 350 nm of a 25 μ M solution while decreasing the temperature, where reversibility is confirmed by the return of the O.D. to baseline. This ELP homopolymer has the sequence SKGPG-(VGVPG)80-Y. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 5. Characterization of ELP diblock copolymer by temperature-programmed turbidimetry and dynamic light scattering. ELPs that undergo nano-scale self-assembly, such as ELP diblock copolymers that self-assemble into spherical micelles, exhibit more complex turbidity profiles. A) Moderate increase in O.D. indicates the transition from unimers to micelles, prior to a rapid increase in O.D. that indicates complete aggregation of the ELP into micron-scale aggregates. B) DLS measurements confirm the behavior inferred from the turbidity profile for a solution at 25 μM by providing information about the change in RH with respect to temperature. Here the ELP unimer has a RH ~8 nm and the micelle has a RH ~25 nm. This ELP diblock copolymer has the sequence GCGWPG-(VGVPG)60-(AGVPGGGVPG)30-PGGS. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Dyskusje

ELPs offer an inexpensive and chromatography-free means of purification by exploitation of their stimulus-responsive phase behavior. This approach takes advantage of the LCST behavior of ELPs and peptide or protein ELP fusions to eliminate both soluble and insoluble contaminants after expression of genetically encoded ELPs in E. coli. This ease of purification can be used to produce ELPs for a variety of applications, or can be exploited for purification of recombinant peptides or proteins in which the ELP can act as a purification tag that may be removed with post-purification processing.

ELP purification involves preliminary steps to lyse the E. coli and remove genomic and insoluble cell debris from the crude culture lysate (Figure 1), followed by removal of residual soluble and insoluble contaminants by ITC (Figure 2). Centrifugation after triggering the ELP transition by the addition of heat or salt separates the ELP from soluble contaminants in the supernatant, in a step termed a hot spin. After resolubilizing the ELP, the solution is centrifuged again at a temperature below the Tt to remove the insoluble contaminant pellet, in a step termed a cold spin. Alternating hot and cold spins improves the purity of the ELP solution with each cycle, at a small cost to yield. Purification yields vary depending on the ELP Tt, length, and fused peptides or proteins. Typically, this protocol yields 100 mg of purified ELP per liter of E. coli culture, however yields can reach up to 500 mg/L. The final purity of the ELP product is confirmed by SDS-PAGE (Figure 3). The MW of the purified ELP should match closely with the theoretical MW encoded by the ELP gene. However, some ELPs migrate in SDS-PAGE with an apparent MW up to 20% higher than their expected MW9,27. More precise analysis of the ELP MW can be achieved by MALDI-TOF-MS, which can also provide additional information on the purity of the ELP product along with orthogonal analytic techniques such as high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Following purification, the ELP Tt is measured by temperature-programmed turbidimetry. This technique monitors the O.D. of an ELP solution while the temperature is increased. The Tt is concentration dependent so it is advisable to characterize a concentration series relevant to the intended application of the ELP. For ELP homopolymers the turbidity profile exhibits a single sharp increase that corresponds to the ELP transition from unimer to micron-scale aggregates (Figure 4A). The Tt is defined as the temperature corresponding to the inflection point in the turbidity profile, precisely determined as the maximum of the first derivative of the O.D. with respect to temperature. The reversibility of the ELP phase transition is confirmed by a decrease in O.D. to baseline as the temperature is lowered below the Tt (Figure 4B). The turbidity profile with increasing and decreasing temperature ramps will differ in magnitude and kinetics due to settling of ELP coacervates and variable hysteresis of ELP resolubilization. Peptide or protein ELP fusions similarly exhibit LCST behavior in this way, where the peptide or protein fused to the ELP affects the Tt. For protein ELP fusions the transition is reversible below the melting temperature of the protein. While temperature-programmed turbidimetry is an excellent method for the initial thermal characterization of ELP products, alternative techniques, such as differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), can also be used to measure the ELP Tt.

ELPs with more complex architectures exhibit more complicated thermal behaviors that can also be characterized by temperature-programmed turbidimetry. ELP diblock copolymers, for example, exhibit a characteristic turbidity profile corresponding to their temperature-triggered self-assembly into spherical micelles at their critical micellization temperature. For such ELP diblock copolymers the O.D. typically first increases 0.1-0.5 units above baseline indicating the transition from unimers to micelles, after which a sharp increase in O.D (up to 2.0 units above baseline) at a higher temperature indicates the formation of micron-scale aggregates (Figure 5A). Additional information about temperature-triggered self-assembled ELP structures is obtained with DLS, a technique that measures the RH of ELP assemblies in solution. Changes in RH agree closely with changes in O.D. measured with turbidimetry (Figure 5B). ELP unimers typically exhibit a RH<10 nm while nanoparticle assemblies exhibit a RH~20-100 nm and aggregates exhibit a RH>500 nm. Additional information about self-assembled ELP nanoparticles, such as aggregation number and morphology, can be obtained by static light scattering or cryogenic transmission electron microscopy17,23,29.

Due to the tunability of ELP thermal properties, a range of Tts is obtained by various ELP designs. It is important to keep in mind that the inherent Tt will influence the optimization of the purification protocol for each ELP, where extremely low or high Tts will require the most modification to this standard protocol. ELPs with extremely high transition temperatures may be unsuitable for purification with this approach. If the design of novel ELPs and peptide or protein ELP fusions may compromise the thermal response of the ELP, a simple histidine tag can be included for alternative purification by immobilized metal affinity chromatography. Additionally, characteristics of the ELP sequence may require modification of this protocol if the guest residue is charged. Manipulation of the buffer pH can be used as a method to change the overall charge of the ELP in an effort to eliminate electrostatic interactions with contaminants17. Furthermore, this protocol is appropriate for the special circumstance of ELP fusions with peptides and proteins when appropriate measures are taken to ensure the purification process does not perturb the activity of the fused moiety. Notes throughout the protocol on such modifications serve to direct the purification of ELPs that may present these challenges with respect to Tt, charge, or fusion concerns.

The purification of ELPs by means of their LCST behavior presents a simple and chromatography-free approach to purify the majority of ELPs and peptide or protein ELP fusions expressed in E. coli. The protocol summarized here permits purification of ELPs in a single day using equipment that is common to most biology laboratories. The ease of purification of ELPs and their fusions will, we hope, encourage an ever-growing diversity of ELP designs for new applications in materials science, biotechnology, and medicine.

Ujawnienia

The authors have no competing financial interests to disclose.

Podziękowania

This work was supported by the NSF’s Research Triangle MRSEC (DMR-1121107).

Materiały

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| pET-24a(+) pET-25b(+) | Novagen | 69749-3 69753-3 | T7-lac expression vectors with resistance to kanamycin (pET-24) or ampicillin (pET-25). |

| Ultra BL21 (DE3) competent cells | Edge BioSystems | 45363 | Competent E. coli for recombinant protein expression. |

| Terrific Broth (TB) Dry Powder Growth Media | MO BIO Laboratories | 12105 | Media is reconstituted in DI H2O and autoclaved before use. |

| Isopropyl-beta-D-thiogalactoside (IPTG) | Gold Biotechnology | I2481C | IPTG is reconstituted in DI H2O, sterile filtered, and added to cultures to induce enhanced expression. |

| Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) tablet | Calbiochem | 524650 | These PBS tablets, when dissolved in 1 L of DI H2O, yield a 10 mM phosphate buffer with 140 mM NaCl, and 3 mM KCl with a pH of 7.4 at 25 °C. |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) Solution (~50% w/v) | MP Biomedicals | 195444 | PEI is prepared as a 10% (w/v) solution in deionized H2O. |

| Nalgene Oak Ridge high-speed centrifuge tubes, 50 ml | Thermo Scientific | 3138-0050 | These round-bottom tubes withstand high-speed centrifugation of 30-50 ml. |

| Tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine hydrochloride (TCEP-HCl) | Thermo Scientific | 20491 | A stock solution of TCEP-HCl is prepared at 100 mM in DI H2O and adjusted to pH 7.0. For ELPs with a high cysteine content the stock solution of this reducing agent is added to the ELP pellet to reach 10 mM in H2O. |

| Ready Gel Tris-HCl gel, 4-20% linear gradient polyacrylamide gel, 10 well, 30 μl | Bio-Rad Laboratories | 161-1105 | These linear gradient gels offer good visualization of ELPs with a range of MWs. |

| Cupric chloride dihydrate (CuCl2·2H2O) | Fisher Scientific | C454-500 | A filtered 0.5 M solution is prepared for negative staining of Tris-HCl polyacrylamide gels. |

| Anotop 10 syringe filter: 0.02 μm 0.1 μm 0.2 μm | Whatman | 6809-1002 6809-1012 6809-1022 | These 10-mm diameter syringe filters allow preparation of small volumes for DLS measurements. |

| Millex-HV filter: 0.45 μm | EMD Millipore | SLHVX13NK | These 13-mm diameter syringe filters allow preparation of small volumes of solutions with large nanoparticle assemblies for DLS measurements. |

Odniesienia

- Urry, D. W. Physical Chemistry of Biological Free Energy Transduction As Demonstrated by Elastic Protein-Based Polymers. J. Phys. Chem. B. 101, 11007-11028 (1997).

- Sallach, R. E., Conticello, V. P., Chaikof, E. L. Expression of a recombinant elastin-like protein in pichia pastoris. Biotechnology progress. 25, 1810-1818 (2009).

- Schipperus, R., Teeuwen, R. L., Werten, M. W., Eggink, G., de Wolf, F. A. Secreted production of an elastin-like polypeptide by Pichia pastoris. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 85, 293-301 (2009).

- Schipperus, R., Eggink, G., de Wolf, F. A. Secretion of elastin-like polypeptides with different transition temperatures by Pichia pastoris. Biotechnology progress. 28, 242-247 (2012).

- Herzog, R. W., Singh, N. K., Urry, D. W., Daniell, H. Expression of a synthetic protein-based polymer (elastomer) gene in Aspergillus nidulans. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 47, 368-372 (1997).

- Conley, A. J., Joensuu, J. J., Jevnikar, A. M., Menassa, R., Brandle, J. E. Optimization of elastin-like polypeptide fusions for expression and purification of recombinant proteins in plants. Biotechnology and bioengineering. 103, 562-573 (2009).

- Conrad, U., et al. ELPylated anti-human TNF therapeutic single-domain antibodies for prevention of lethal septic shock. Plant biotechnology journal. 9, 22-31 (2011).

- Kaldis, A., et al. High-level production of human interleukin-10 fusions in tobacco cell suspension cultures. Plant biotechnology journal. 11, 535-545 (2013).

- Meyer, D. E., Chilkoti, A. Genetically encoded synthesis of protein-based polymers with precisely specified molecular weight and sequence by recursive directional ligation: examples from the elastin-like polypeptide system. Biomacromolecules. 3, 357-367 (2002).

- McDaniel, J. R., Mackay, J. A., Quiroz, F. G., Chilkoti, A. Recursive directional ligation by plasmid reconstruction allows rapid and seamless cloning of oligomeric genes. Biomacromolecules. 11, 944-952 (2010).

- Amiram, M., Quiroz, F. G., Callahan, D. J., Chilkoti, A. A highly parallel method for synthesizing DNA repeats enables the discovery of 'smart' protein polymers. Nat Mater. 10, 141-148 (2011).

- Meyer, D. E., Chilkoti, A. Quantification of the effects of chain length and concentration on the thermal behavior of elastin-like polypeptides. Biomacromolecules. 5, 846-851 (2004).

- Urry, D. W., et al. Temperature of Polypeptide Inverse Temperature Transition Depends on Mean Residue Hydrophobicity. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 113, 4346-4348 (1991).

- Urry, D. W. The change in Gibbs free energy for hydrophobic association - Derivation and evaluation by means of inverse temperature transitions. Chem Phys Lett. 399, 177-183 (2004).

- Cho, Y., et al. Effects of Hofmeister anions on the phase transition temperature of elastin-like polypeptides. The journal of physical chemistry. B. 112, 13765-13771 (2008).

- Kim, B., Chilkoti, A. Allosteric actuation of inverse phase transition of a stimulus-responsive fusion polypeptide by ligand binding. J Am Chem Soc. 130, 17867-17873 (2008).

- Hassouneh, W., Nunalee, M. L., Shelton, M. C., Chilkoti, A. Calcium binding peptide motifs from calmodulin confer divalent ion selectivity to elastin-like polypeptides. Biomacromolecules. 14, 2347-2353 (2013).

- Nettles, D. L., Chilkoti, A., Setton, L. A. Applications of elastin-like polypeptides in tissue engineering. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 62, 1479-1485 (2010).

- MacEwan, S. R., Chilkoti, A. Elastin-like polypeptides: biomedical applications of tunable biopolymers. Biopolymers. 94, 60-77 (2010).

- McDaniel, J. R., Callahan, D. J., Chilkoti, A. Drug delivery to solid tumors by elastin-like polypeptides. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 62, 1456-1467 (2010).

- Hassouneh, W., Christensen, T., Chilkoti, A. Elastin-like polypeptides as a purification tag for recombinant proteins. Curr Protoc Protein Sci. , (2010).

- Shamji, M. F., et al. Development and characterization of a fusion protein between thermally responsive elastin-like polypeptide and interleukin-1 receptor antagonist: sustained release of a local antiinflammatory therapeutic. Arthritis Rheum. 56, 3650-3661 (2007).

- Hassouneh, W., et al. Unexpected multivalent display of proteins by temperature triggered self-assembly of elastin-like polypeptide block copolymers. Biomacromolecules. 13, 1598-1605 (2012).

- Lan, D. M., et al. An improved nonchromatographic method for the purification of recombinant proteins using elastin-like polypeptide-tagged proteases. Analytical Biochemistry. 415, 200-202 (2011).

- Bellucci, J. J., Amiram, M., Bhattacharyya, J., McCafferty, D., Chilkoti, A. Three-in-one chromatography-free purification, tag removal, and site-specific modification of recombinant fusion proteins using sortase A and elastin-like polypeptides. Angewandte Chemie. 52, 3703-3708 (2013).

- Compton, S. J., Jones, C. G. Mechanism of dye response and interference in the Bradford protein assay. Anal Biochem. 151, 369-374 (1985).

- McPherson, D. T., Xu, J., Urry, D. W. Product purification by reversible phase transition following Escherichia coli expression of genes encoding up to 251 repeats of the elastomeric pentapeptide GVGVP. Protein expression and purification. 7, 51-57 (1996).

- Meyer, D. E., Chilkoti, A. Purification of recombinant proteins by fusion with thermally-responsive polypeptides. Nat Biotechnol. 17, 1112-1115 (1999).

- McDaniel, J. R., et al. Self-assembly of thermally responsive nanoparticles of a genetically encoded peptide polymer by drug conjugation. Angewandte Chemie. 52, 1683-1687 (2013).

Przedruki i uprawnienia

Zapytaj o uprawnienia na użycie tekstu lub obrazów z tego artykułu JoVE

Zapytaj o uprawnieniaThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone