Case Report

烟罩和层流柜

Not Published

摘要

实体进入这里度:微:μ符å·ï¼šå•†æ ‡ï¼šæµ‹è¯•âˆ‚ΣΩ≈γγδγδγδ测试

摘要

罗伯特 m Rioux & 威廉 a. 艾略特, 宾夕法尼亚州立大学, 大学公园, PA

通风罩和层流柜是在类似原理下运行的工程控制装置。两者都使用恒定的气流来防止实验室环境及其居民受到污染。油烟罩防止有害物质退出引擎盖工作区, 而层流柜则防止污染物进入机柜工作区.

通风系统是为了尽量减少暴露在有害的蒸气、烟雾和微粒上而设计的。空气的恒定流动被画入敞篷开头, 限制蒸气、烟雾和微粒的逃命, 然后被拉扯通过排气。层流柜被用来维持一个无菌/清洁的环境由不断流动的高效率微粒 arrestance (高效空气过滤) 的气体向外, 最大限度地减少污染空气进入内阁工作空间。经高效过滤的空气减少了有害化学物质或微粒进入实验室的机会。高效过滤器可去除99.97% 或更大的0.3 和 #181; m 粒子.

引言

通风罩和层流柜是工程控制, 旨在减少风险和污染。油烟罩减少了对用户有害气体、烟雾和微粒的接触, 而层流柜则减少了工作环境暴露于污染物。紊流遵循不规则的流动模式, 局部流动相对于散流流动。层流流动的平行流线, 不交叉。层流柜保持层流的空气, 以防止在工作空间内的交叉污染, 并防止污染空气从外部的引擎盖, 将发生湍流流回流.

研究方案

1. 油烟罩

- 使用

- 烟罩用于产生有害的蒸气、烟雾或空气颗粒, 如细二氧化硅粉或挥发性致癌物, 如苯.

- 操作

- 空气被绘制在引擎盖的开口面, 用户工作的地方, 并通过排气口。不断向内流动的空气, 以防止危险的蒸气, 烟雾, 和微粒从逃生通过引擎盖开放, 使用户和其他实验室工作人员的安全.

- 面部流速必须足够高, 以使引擎盖有效。低流速可以使有害的烟雾、蒸气或微粒通过打开引擎盖向用户逃生。一个低流速的原因是有可调整的窗口在敞篷开头, 被称为窗扇, 太高。油烟罩具有低流速报警和窗扇高度报警是常见的。典型的流速是在0.41 和0.51 米/秒之间 (ANSI/AIHA/ASSE Z9.5)。罩应有明确标明的窗扇的最大安全工作高度.

- 有几个安全使用通风罩的规则。

- 永远不要把头放在引擎盖上, 因为把头插在引擎盖里会暴露出有害的物质。引擎盖的设计是为了保护用户在使用时不受化学物质的照射。只有用户和 #39; 武器应该存在于引擎盖中。在任何时候都要穿戴适当的个人防护装备 (PPE), 而不管油烟机所提供的保护。咨询您的组织和 #39 的环境健康和 #38; 安全 (EHS) 办公室为适当的 PPE 建议, 如果他们是未知的.

- 始终在最大安全高度或下方使用窗扇.

- 不使用时, 窗扇应关闭。关闭窗扇, 确保了一个更安全的工作环境, 为所有实验室住户。此外, 与不适当的油烟罩操作相关的能源成本是巨大的。保持窗扇高度最低, 非工作日的水平是更节能.

- 不要使用引擎盖进行化学存储。在适当的地点储存化学品, 如易燃的柜子, 并在需要时将其带入油烟罩.

- 将所有材料放在油烟罩中至少6英寸处, 远离油烟罩面的边缘。当工作是在6英寸的边缘进行, 蒸气, 烟雾, 和颗粒更有可能逃脱.

- 正如良好的内务管理原则适用于工作实验室工作台, 同样的原则应在油烟罩内实行.

- 对通风罩进行定期维护, 以确保其安全运行。维修应包括测试报警和测试流速在设计操作窗扇位置。许多因素会影响水流速度, 包括引擎盖所在房间内的水流模式和排气口的障碍物。如果在设计操作窗扇位置的流速较低, 请将窗扇向下, 直到流速达到所需速度。许多现代油烟罩都有空气流速监测器, 实时监测流速。如果窗扇变得太低, 在油烟罩上进行有效的工作, 停止操作, 直到问题的根源解决.

- 油烟罩变化

- 有可能遇到的更专业的通风罩类型的数量。这些包括高氯酸罩, 放射性同位素罩, 无罩, 和其他。更多可以阅读关于这些在 ANSI/AIHA/ASSE Z9.5 的要求.

2。层流柜

- 使用

- 层流柜使用时, 清洁环境, 无颗粒或生物污染物, 是必需的。常见的例子包括使用组织培养或半导体晶片。层流柜防止空气污染进入机柜工作空间。空气的层流 (与湍流相反) 最大限度地减少了箱体内样品的交叉污染.

- 空气由高效过滤器筛选并在工作区中被吹出, 向用户。不断向外流动的清洁空气保持一个未污染的工作空间。一些层流柜装有 UV C 灯, 以便在使用前对工作区进行消毒.

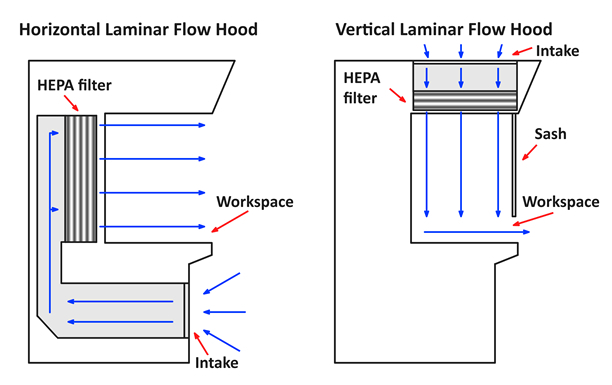

- 有两种类型的层流机柜: 水平流和垂直流 ( 图 1 )。水平流柜从机柜的背面向用户水平吹净空气, 而垂直流罩将清洁空气从机柜的天花板吹向工作区的地板, 然后将其击中底座并在水平方向上流动。向用户的方向。垂直的流动橱柜使用与窗扇拉下来。水平流柜没有窗扇。两种类型的层流柜都有其优缺点.

图 1 。水平和垂直层流罩图.

| 水平层流流罩 | |

| 优势 | 缺点 |

| 手/手套的污染较少, 因为它们通常是在机柜中的项目的顺风, 用户和 #8217; s 的脸 | |

| worksp 上的大对象ace 可以阻止空气流动, 降低效率 | |

| 垂直层流罩 | |

| 优点 | 的缺点 |

| 流不吹在用户和 #8217; s 的脸 | 无法将手和手臂放在对象上方 |

| 工作区中的项目交叉污染 | 增加气流湍流 |

表1。水平和垂直层流罩的优缺点.

- 提示, 确保有效使用层流柜。

- 始终注意不要将项目置于可能导致交叉污染的项目下游。这在使用生物样品时尤其重要.

- 最小化杂波。柜中的物料越多, 可能发生的污染就越大。大项目可能会打乱流程.

- 确保在进入机柜前, 手/手套和任何带进机柜的物品都不受污染.

- 所有项目必须放在6英寸或更远的距离, 从内阁开幕的边缘。在6英寸的边缘的空气更可能与外部空气混合, 这意味着6英寸内的物体更容易受到污染.

- 应在层流机柜上进行定期维护, 以确保其安全运行。维护应包括检查和更换高效空气过滤器, 检查机柜是否有泄漏, 以及测试气流速度。通过测试通过过滤器的微粒的数量, 可以检查空气过滤器的完整性。过滤器应删除99.97% 或更大的0.3 和 #181; m 粒子。如果流速太低, 橱柜将无法有效地保持污染物。如果流速太大, 流动将是湍流, 污染变得更有可能.

油烟罩和层流柜是实验室设备的必备部件, 可防止危险情况和污染.

在通风罩和层流柜中, 使用气流减少危险或污染物。油烟罩通过工作空间吸引空气, 去除有害气体和微粒, 而层流机柜通过过滤器吹气, 防止灰尘或生物物质污染样品.

此视频将说明通风罩和层流柜如何操作、如何使用以及如何进行维护.

通风罩和层流柜使用层流气流进行操作, 这是一种平行流线的流动, 不交叉。层流, 而不是湍流流动, 防止交叉污染的样品之间流动的对象清除危险粒子.

油烟罩有三大部分: 带窗扇的开口面、工作区和排气口。排气扇通过开面, 穿过工作区, 穿过排气口吸引空气。这一流动反过来引出尾气中的烟雾和微粒, 远离实验室.

在适当的高度, 窗扇限制了开口的大小, 这反过来又维持了高气流。这种高流量是防止烟雾逸出所必需的.

同时, 有两种类型的层流柜, 水平和垂直。在这两种情况下, 空气是通过吸收和净化过滤器, 它是清除的小颗粒, 如灰尘和细菌.

水平机柜通过工作区水平方向的空气。这种类型的橱柜减少了手和手套的污染, 因为它们是样品的下游。然而, 气流确实直接吹向用户, 大的物体会阻碍流动.

在垂直的机柜中, 将空气从上方定向到工作区, 然后通过窗扇。由于这种类型的流直接接触到工作区材料的表面, 它有助于防止交叉污染。然而, 窗扇可以限制手的移动和气流比在一个水平的内阁更动荡.

现在, 我们将向您展示如何在实验室设置中使用这些工作区以及如何执行基本维护.

要安全地使用通风罩, 请始终佩戴适当的个人防护设备。提高窗扇只到指示的最大安全工作高度确保足够的气流通过引擎盖.

防止接触有害的烟雾或微粒, 只用你的手臂在引擎盖内, 不要让你的头进入工作空间。此外, 为了确保速度是足够的整个引擎盖, 保持工作区整洁, 并移动所有项目至少六英寸的敞篷脸.

当您完成在引擎盖上工作时, 取出所有材料。不要在引擎盖上存放化学品, 而是在一个专门的存储位置, 如易燃柜。最后, 关闭窗扇, 以确保一个更安全的实验室环境和减少能源使用.

通过测试警报和最大窗扇高度的流速来执行常规维护.

如果速度较低, 则将窗扇降低到所需的速度。如果窗扇太低, 无法在引擎盖上完成工作, 则停止操作直到解决问题的根源.

层流柜通常用于污染问题的地方, 如生物实验室, 因此您需要小心自己和实验室空气的污染。为了防止污染, 使用乙醇消毒手套和任何设备, 然后再使用橱柜或打开窗扇.

确保窗扇不超过最大允许高度, 以确保足够的空气流通。保持柜子不受杂波的干扰, 并确保物体被放置在离边缘至少6英寸的地方, 因为这是最有可能被实验室空气污染的区域。另外, 不要将项目置于彼此交叉污染的危险中.

完成后, 从工作区中删除所有项目以防止杂乱并关闭窗扇以防止污染。然后, 如果机柜装有 UV C 光, 请将其打开以对工作区进行消毒.

对层流柜进行定期维护。通过涂布边缘的敏感区域 (如带肥皂液的窗框) 来检查是否有泄漏, 这将在逃逸空气的地方起泡.

您刚刚看了朱庇特介绍的油烟罩和层流柜。现在, 您应该了解它们的工作方式、如何使用它们以及如何执行维护。谢谢收看!

结果

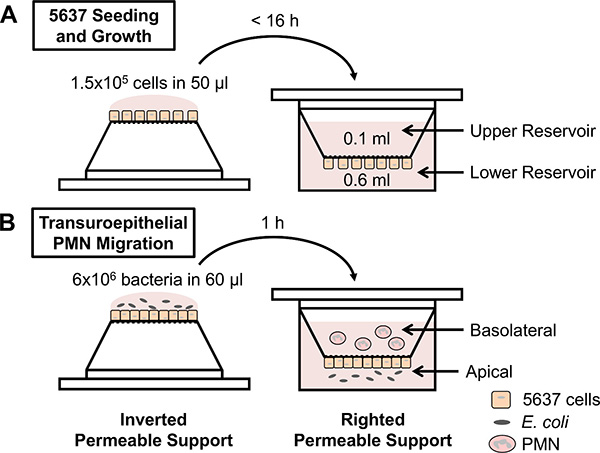

ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞è¿ç§»å®žéªŒtransuroepithelial使人体ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞培养的膀胱上皮细胞层之间è¿ç§»çš„定é‡è¯„估,对å„ç§åˆºæ¿€çš„å应(图1B)。虽然该å议是简å•çš„,有一些å˜é‡ï¼Œå¯ä»¥å½±å“ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞的è¿ç§»ï¼Œä»Žè€Œå½±å“该测定的å¯å†çŽ°æ€§ã€‚应采å–措施,åŒæ—¶å‡†å¤‡æ¸—é€æ€§æ”¯æŒå’Œä¸æ€§ç²’细胞å‡å°‘技术和生物之间的å¤åˆ¶å˜å¼‚。例如,åªæœ‰å¯æ¸—é€çš„支æŒåŒ…å«åœ¨ä¸€ä¸ªå®žéªŒä¸ï¼Œåº”使用足够汇åˆ5637细胞层。 5637细胞的åˆæµæ˜¯ä½¿ç”¨åŠŸèƒ½æµ‹å®šï¼Œæµ‹é‡æ¶²ä½“的抗渗评估的。如果介质ä¸ï¼Œç„¶åŽæ·»åŠ 到å¯æ¸—é€çš„支æŒä¸Šæ°´åº“达到平衡跨越5637细胞ä¸èƒ½å……分地汇åˆæ¥è¿›è¡Œå®žéªŒã€‚如果音é‡ç»´æŒåœ¨ä¸Šæ°´åº“,然åŽå¯ç”¨äºŽå¯æ¸—é€çš„支æŒï¼Œä»¥è¯„ä¼°ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞的è¿ç§»ã€‚在这个系统ä¸ï¼Œæ±‡åˆçš„细胞åŽï¼Œæ¸©å’Œä¸Šå‡ï¼Œæˆ‘们测é‡è·¨ä¸Šçš®ç”µé˜»ï¼Œå¦‚果选择æ¤æ–¹æ³•ï¼Œåº”å°å¿ƒï¼Œä¸è¦æ±¡æŸ“å…¶ä»–æ— èŒçš„设置。åˆæµçš„5637细胞æ’ç§åŽ7天å¯ä»¥å—到多ç§å› ç´ çš„å½±å“ï¼ŒåŒ…æ‹¬ç»†èƒžçš„ä¼ ä»£æ¬¡æ•°å’Œæ•°é‡çš„细胞接ç§åœ¨é€æ°”性支承。æ¤å¤–,5637细胞培养在倒置的ä½ç½®ä¸Šçš„é€æ°”性支承在æ’ç§è¿‡ç¨‹ä¸çš„时间é‡åº”ä¸è¶…过16å°æ—¶ï¼ˆå›¾1A)。为了获得最佳的é‡çŽ°æ€§ï¼Œè¯¥å议应éµå¾ªç²¾ç¡®ã€‚最åŽï¼Œå¯æ¸—é€çš„支æŒåº”在1-2天内使用å«æœ‰æ±‡åˆçš„5637细胞层,支撑膜5637细胞的生长或在transuroepithelialä¸æ€§ç²’细胞è¿ç§»å®žéªŒè¿‡ç¨‹ä¸ï¼Œæ— 论是永远ä¸ä¼šè¢«è§¦åŠã€‚

在除了5637细胞ä¸ï¼Œå˜å¼‚性也å¯ä»¥è¢«ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞制备过程ä¸å¼•å…¥ã€‚使用上文详述的å议隔离PMN,1毫å‡äººä½“血液ä¸é€šå¸¸äº§ç”Ÿçº¦10 6 PMN,尽管这一数é‡ä»Žä¸ªäººåˆ°ä¸ªäººã€‚一旦个别æèµ è€…çš„è¡€æ¶²ä¸çš„典型的产率是已知的,å¯ä»¥æŒ‰æ¯”例放大的隔离å议或å‘下。ä¸å¥åº·æˆ–è™å¾…个人应é¿å…ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞,生物å¤åˆ¶ä»¥ç¡®ä¿è§‚察的结果是å¯é‡å¤çš„,应该使用ä¸åŒçš„ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞æ献者。ä¸æ€§ç²’ç»†èƒžï¼Œåº”è½»æ‹¿è½»æ”¾ï¼Œæ— èŒéš”离期间,以é¿å…激活。最åŽçš„实验程åºï¼Œå®šæ—¶æ˜¯è‡³å…³é‡è¦çš„,如ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞ä¸å˜æ´»ä¸€æ—¦ä»Žäººä½“å–出的长时间。我们利用ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞在1å°æ—¶å†…完æˆåˆ†ç¦»è¿‡ç¨‹ã€‚鉴于这些考虑,至少3个技术é‡å¤åº”包括在æ¯ä¸ªç”Ÿç‰©å¤åˆ¶ã€‚

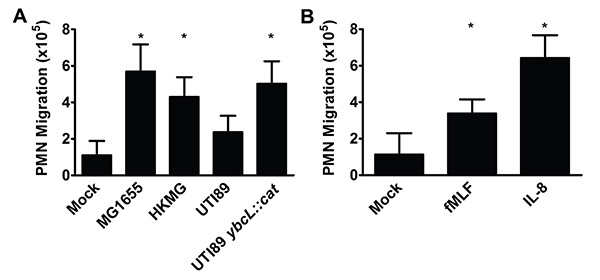

1å°æ—¶åŽï¼Œåœ¨è¾ƒä½Žçš„储层PMN的数目是图2所示的归一化至10 6个输入的PMN。å¦å¤–,ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞数å¯ä»¥ç›¸æ¯”内部控制æ£å¸¸åŒ–åŽè¾“å…¥ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞,这å¯èƒ½ä¼šé™ä½Žç”Ÿç‰©å¤åˆ¶ä¹‹é—´çš„差异。å“应刺激,包括细èŒï¼ˆå›¾2A)和趋化物质(图2B)åšæŒçš„å议上文所述,注é‡ç»†èŠ‚,使ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞è¿ç§»çš„枚举。

图1。实验设计的原ç†å›¾ï¼Œï¼ˆA)5637膀胱上皮细胞接ç§äºŽå€’å¯æ¸—é€æ”¯æ’‘ï¼Œæ”¯æ’‘è¢«çº æ£åˆ°ä¸€ä¸ª24å”培养æ¿ä¸ï¼Œå¹¶å°†ç»†èƒžç”Ÿé•¿è‡³æ±‡åˆã€‚ (B)é€æ°´æ”¯æŒå«åˆæµ5637细胞的端å£åè½¬ï¼Œå¹¶ä¸Žå¤§è‚ æ†èŒæ„ŸæŸ“å¤§è‚ æ†èŒä¸Šçš„æ ¹å°–ä¾§çš„ä¸Šçš®ç»†èƒžå±‚ã€‚æ¤å¤–ï¼Œè¶‹åŒ–å› å,å¯ä»¥è¢«æ”¾ç½®åœ¨è¾ƒä½Žçš„储层。到一个低安装æ¿æ‰¶æ£çš„å¯æ¸—é€æ”¯æ’‘ï¼Œæ–½åŠ åˆ°ä¸Šæ°´åº“ï¼ˆå³ä¸Šçš®ç»†èƒžå±‚的基底侧)新鲜分离的人ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞。ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞之间è¿ç§»çš„上皮细胞和从下水库利用血çƒåˆ—举。

图2。ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞è¿ç§»æ•´ä¸ªè†€èƒ±ä¸Šçš®ç»†èƒžåœ¨å„ç§åˆºæ¿€çš„å应(A)与éžè‡´ç—…æ€§å¤§è‚ æ†èŒæ„ŸæŸ“å¤§è‚ æ†èŒ MG1655æ ªï¼Œçƒæ€MG1655的(HKMG)或连è¥çªå˜UTI89 ybcLçš„::猫引起显ç€æ›´å¤šçš„ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞的è¿ç§»æ¯”莫UPECèŒæ ªä¸Žé‡Žç”Ÿåž‹UTI89 CK感染或感染,分离膀胱炎(*,P <0.001)。 (B)本fMLF(100纳米)或IL-8(100毫微克/毫å‡ï¼‰åŠ 入到下水库(*,P <0.001)比模拟处ç†ç»“果显ç€æ›´å¤šçš„ä¸æ€§ç²’细胞的è¿ç§»ã€‚æ•°æ®ä»£è¡¨çš„至少有3个生物å¦é‡å¤çš„å¹³å‡å€¼å’Œæ ‡å‡†å差。统计å¦æ˜¾ç€æ€§å·®å¼‚的确定,采用éžé…对t检验。

讨论

油烟罩和层流柜是实验室中有用的工具, 可以防止有害物质的危害, 并在使用敏感材料时保持清洁的工作空间。然而, 烟罩和层流柜只有在正确使用时才有效。按照简单的操作准则和定期维护, 油烟机和层流柜可以成为实验室的有效工具.

披露声明

泄露

致谢

材料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| (3-Glycidyloxypropyl)trimethoxysilane | Sigma | 440167 | GOPS |

| 0.25% Trypsin-EDTA (1X) | Gibco | 25200-056 | |

| 4-Dodecylbenzenesulfonic acid | Sigma | 44198 | DBSA |

| 96-well plate | Falcon | 353075 | |

| Acetone | Technic | 530 | |

| Acrylic resin | Fischer scientific | NC1455685 | |

| agarose | Sigma | A9539 | |

| autoclave | Tuttnauer | 3150 EL | |

| AZ 10XT | Microchemicals | Positive photoresist | |

| AZ 826 MIF Developer | Merck | 10056124960 | Metal-ion-free developer for the negative photoresist |

| AZ Developer | Merck | 10054224960 | Metal-ion-free developer for the positive photoresist |

| AZ nLof 2070 | Microchemicals | Negative photoresist | |

| Buprenorphine | Axience | ||

| Carprofen | Rimadyl | ||

| Centrifuge Sorvall Legend X1R | Thermo Scientific | 75004260 | |

| CMOS camera Prime 95B | Photometrics | ||

| CO2 incubator HERAcell 150i | Thermo scientific | ||

| DAC board | National Instruments | USB 6259 | |

| Déco spray Pébéo | Cultura | 3167860937307 | Black acrylic paint |

| Dextran Texas Red 70.000 | Thermofisher | D1830 | |

| Die bonding paste "Epinal" | Hitachi | EN-4900GC | Silver paste |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide | Sigma | D2438 | |

| Dispensing machine | Tianhao | TH-2004C | |

| Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium + GlutaMAX™-I | Gibco | 10567-014 | |

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium | Sigma | D6429 | |

| Egg incubator COUVAD'OR 160 | lafermedemanon.com | ||

| Ethylene glycol | Carl Roth | 6881.1 | |

| Fertilized eggs of Japanese quail | Japocaille | ||

| Fetal Bovine Serum | VWR | S181BH | |

| Flask | Greiner | 658170 | |

| Fluorescence macroscope | Leica MZFLIII | ||

| Gl261 | DSMZ | ACC 802 | |

| Gold pellets - Dia 3 mm x 6 mm th | Neyco | ||

| Handheld automated cell counter | Millipore | PHCC00000 | |

| Heating and drying oven | Memmert | UF110 | |

| Hexadimethrine Bromide Sequa-brene | Sigma | S2667 | |

| hot plate Delta 6 HP 350 | Süss Microtec | ||

| Illumination system pE-4000 | CoolLed | ||

| Infrared tunable femtosecond laser (Maï-Taï) | Spectra Physics (USA) | ||

| Ionomycin calcium salt | Sigma | I3909 | |

| Kapton tape SCOTCH 92 33x19 | 3M | Polyimide protection tape | |

| Lab made pulse generator | |||

| Labcoter 2 Parylene Deposition system PDS 2010 | SCS | ||

| Lenti-X 293 T cell line | Takara Bio | 63218 | HEK 293T-derived cell line optimized for lentivirus production |

| Lenti-X GoStix Plus | Takara Bio | 631280 | Quantitative lentiviral titer test |

| Mask aligner MJB4 | Süss Microtec | ||

| Micro-90 Concentrated cleaning solution | International Products | M9050-12 | |

| Microscope slides 76 x 52 x 1 mm | Marienfeld | 1100420 | |

| Needles 30G | BD Microlance 3 | 304000 | |

| PalmSens4 potentiostat | PalmSens | ||

| parylene-c : dichloro-p-cyclophane | SCS | 300073 | |

| PCB Processing Tanks | Mega Electronics | PA104 | |

| PEDOT:PSS Clevios PH 1000 | Heraeus | ||

| penicillin / streptomycin | Gibco | 15140-122 | |

| Petri dish | Falcon | 351029 | |

| pGP-CMV-GCaMP6f | Addgene | 40755 | plasmid |

| Phosphate Buffer Saline solution | Thermofisher | D8537 | |

| Plasma treatment system PE-100 | Plasma Etch | ||

| PlasmaLab 80 Reactive Ion Etcher | Oxford Instruments | ||

| Plastic mask | Selba | ||

| Plastic weigh boat 64 x 51 x 19 mm | VWR | 10770-454 | |

| Poly-dimethylsiloxane: SYLGARD 184 Silicone Elastomer Kit | Dow chemicals | 1673921 | |

| Polyimide copper film 60 µm (Kapton) | Goodfellow | IM301522 | |

| Propan-2-ol | Technic | 574 | |

| Protolaser S | LPKF | ||

| puromycin | Gibco | A11103 | |

| Round cover glass 5 mm diameter | Fischer scientific | 50-949-439 | |

| Scepter Sensors - 60 µm | Millipore | PHCC60050 | |

| Silicone adhesive Kwik-Sil | World Precision Instruments | ||

| spin coater | Süss Microtec | ||

| Spin Coater | Laurell | WS-650 | |

| Super glue | Office depot | ||

| tetracycline-free fœtal bovine Serum | Takara Bio | 631105 | |

| Thermal evaporator Auto 500 | Boc Edwards | ||

| Two-photon microscope | Zeiss LSM 7MP | ||

| U87-MG | ATCC | HTB-14 | Human glioblastoma cells |

| Ultrasonic cleaner | VWR | ||

| Vortex VTX-3000L | LMS | VTX100323410 | |

| Xfect single shots reagent | Takara Bio | 631447 | Transfection reagent |

参考文献

- Mukund, K., Subramaniam, S. Skeletal muscle: A review of molecular structure and function. in health and disease. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Syst Biol Med. 12 (1), 1462 (2020).

- Feige, P., Brun, C. E., Ritso, M., Rudnicki, M. A. Orienting muscle stem cells for regeneration in homeostasis, aging, and disease. Cell Stem Cell. 23 (5), 653-664 (2018).

- Mauro, A. Satellite cell of skeletal muscle fibers. J Biophys Biochem Cytol. 9 (2), 493-495 (1961).

- Seale, P., et al. Pax7 is required for the specification of myogenic satellite cells. Cell. 102 (6), 777-786 (2000).

- Fuchs, E., Blau, H. M. Tissue stem cells: Architects of their niches. Cell Stem Cell. 27 (4), 532-556 (2020).

- Hernández-hernández, J. M., et al. The myogenic regulatory factors, determinants of muscle development, cell identity and regeneration. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 72, 10-18 (2017).

- Zammit, P. S. Function of the myogenic regulatory factors Myf5, MyoD, Myogenin and MRF4 in skeletal muscle, satellite cells and regenerative myogenesis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 72. , 19-32 (2017).

- Sabourin, L. A. The molecular regulation of myogenesis. Clin Genet. 1 (1), 16-25 (2000).

- Cooper, R. N., et al. In vivo satellite cell activation via Myf5 and MyoD in regenerating mouse skeletal muscle. J Cell Sci. 112 (17), 2895-2901 (1999).

- Rudnicki, M. A., Jaenisch, R. The MyoD family of transcription factors and skeletal myogenesis. Bioessays. 17 (3), 203-209 (1995).

- Braun, T., Arnold, H. H. Inactivation of Myf-6 and Myf-5 genes in mice leads to alterations in skeletal muscle development. EMBO J. 14 (6), 1176-1186 (1995).

- Yablonka-Reuveni, Z. Development and postnatal regulation of adult myoblasts. Microsc Res Tech. 30 (5), 366-380 (1995).

- Braun, T., et al. MyoD expression marks the onset of skeletal myogenesis in Myf-5 mutant mice. Development. 120 (11), 3083-3092 (1994).

- Rudnicki, M. A., et al. MyoD or Myf-5 is required for the formation of skeletal muscle. Cell. 75 (7), 1351-1359 (1993).

- Montarras, D., et al. Developmental biology: Direct isolation of satellite cells for skeletal muscle regeneration. Science. 309 (5743), 2064-2067 (2005).

- Sacco, A., Doyonnas, R., Kraft, P., Vitorovic, S., Blau, H. M. Self-renewal and expansion of single transplanted muscle stem cells. Nature. 456 (7221), 502-506 (2008).

- Cerletti, M., et al. Highly efficient, functional engraftment of skeletal muscle stem cells in dystrophic muscles. Cell. 134 (1), 37-47 (2008).

- Liu, L., Cheung, T. H., Charville, G. W., Rando, T. A. Isolation of skeletal muscle stem cells by fluorescence-activated cell sorting. Nat Protoc. 10 (10), 1612-1624 (2015).

- Porpiglia, E., et al. High-resolution myogenic lineage mapping by single-cell mass cytometry. Nat Cell Biol. 19 (5), 558-567 (2017).

- Behbehani, G. K., Bendall, S. C., Clutter, M. R., Fantl, W. J., Nolan, G. P. Single-cell mass cytometry adapted to measurements of the cell cycle. Cytometry Part A. 81 (7), 552-566 (2012).

- Hartmann, F. J., et al. . Mass Cytometry: Methods and Protocols. , (2019).

- Devine, R. D., Behbehani, G. K. Use of the pyrimidine analog, 5-iodo-2'-deoxyuridine (IdU) with cell cycle markers to establish cell cycle phases in a mass cytometry platform. J Vis Exp. 176, 60556 (2021).

- Bendall, S. C., et al. Single-cell mass cytometry of differential immune and drug responses across a human hematopoietic continuum. Science. 332 (6030), 687-696 (2011).

- Nag, A. C., Foster, J. D. Myogenesis in adult mammalian skeletal muscle in vitro. J Anat. 132 (Pt. 1, 1-18 (1981).

- Le Moigne, A., et al. Characterization of myogenesis from adult satellite cells cultured in vitro). Int J Dev Biol. 34, 171-180 (1990).

- Yablonka-Reuveni, Z. Development and postnatal regulation of adult myoblasts. Microsc Res Tech. 30 (5), 366-380 (1995).

- Chu, C., Cogswell, J., Kohtz, D. S. MyoD functions as a transcriptional repressor in proliferating myoblasts. J Biol Chem. 272 (6), 3145-3148 (1997).

- Shah, B., Hyde-Dunn, J., Jones, G. E. Proliferation of murine myoblasts as measured by bromodeoxyuridine incorporation. Methods in Mol Biol. 75, 349-355 (1997).

- Springer, M. L., Blau, H. M. High-efficiency retroviral infection of primary myoblasts. Somat Cell Mol Genet. 23 (3), 203-209 (1997).

- Rando, T. A., Blau, H. M. Primary mouse myoblast purification, characterization, and transplantation for cell-mediated gene therapy. J Cell Biol. 125 (6), 1275-1287 (1994).

- Springer, M. L., Rando, T. A., Blau, H. M. Gene delivery to muscle. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. Chapter 13, Unit13.4. , (2002).

- Cull-Candy, S. G., Fohlman, J., Gustavsson, D., Lullmann-Rauch, R., Thesleff, S. The effects of taipoxin and notexin on the function and fine structure of the murine neuromuscular junction. Neuroscience. 1 (3), 175-180 (1976).

- Francis, B., John, T. R., Seebart, C., Kaiser, New toxins from the venom of the common tiger snake (Notechis scutatus scutatus). Toxicon. 29 (1), 85-96 (1991).

- Navarro, K. a. e. l. a. L., Monika Huss, ., Smith, J. e. n. n. i. f. e. r. C., Patrick Sharp, . . James O Marx, Cholawat Pacharinsak, Mouse Anesthesia: The Art and Science, ILAR Journal. 62, 1-2 (2021).

- Langford, D., Bailey, A., Chanda, M., et al. Coding of facial expressions of pain in the laboratory mouse. Nat Methods. 7, 447 (2010).

- Matsumiya LC, ., Sorge RE, . Sotocinal SG, Tabaka JM, Wieskopf JS, Zaloum A, King OD, Mogil JS. Using the Mouse Grimace Scale to reevaluate the efficacy of postoperative analgesics in laboratory mice. J Am Assoc Lab Anim Sci. 2012 (1), 42-49 (2012).

- Gonzalez, V. D., et al. High-grade serous ovarian tumor cells modulate NK cell function to create an immune-tolerant microenvironment. Cell Rep. 36 (9), 109632 (2021).

- Delgado-Gonzalez, A., et al. Measuring trogocytosis between ovarian tumor and natural killer cells. STAR Protoc. 3 (2), 101425 (2022).

- Finck, R., et al. Normalization of mass cytometry data with bead standards. Cytometry Part A. 83 (5), 483-494 (2013).

- Leipold, M. D., Maecker, H. T. Mass cytometry: protocol for daily tuning and running cell samples on a CyTOF mass cytometer. J Vis Exp. 69, (2012).

- McCarthy, R. L., Duncan, A. D., Barton, M. C. Sample preparation for mass cytometry analysis. J Vis Exp. 122, 54394 (2017).

- Kotecha, N., Krutzik, P. O., Irish, J. M. Web-based analysis and publication of flow cytometry experiments. Curr Protoc Cytom. Chapter 10., Uni10.17. , (2010).

- Fienberg, H. G., Simonds, E. F., Fantl, W. J., Nolan, G. P., Bodenmiller, B. A platinum-based covalent viability reagent for single-cell mass cytometry. Cytometry Part A. 81 (6), 467-475 (2012).

- Kimball, A. K., et al. A beginner's guide to analyzing and visualizing mass cytometry data. J Immunol. 200 (1), 3-22 (2018).

- Weber, L. M., Robinson, M. D. Comparison of clustering methods for high-dimensional single-cell flow and mass cytometry data. Cytometry Part A. 89 (12), 1084-1096 (2016).

- Samusik, N., Good, Z., Spitzer, M. H., Davis, K. L., Nolan, G. P. Automated mapping of phenotype space with single-cell data. Nat Methods. 13 (6), 493-496 (2016).

- Ornatsky, O. I., et al. Study of cell antigens and intracellular DNA by identification of element-containing labels and metallointercalators using inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 80 (7), 2539-2547 (2008).

- Relaix, F., et al. Perspectives on skeletal muscle stem cells. Nat Commun. 12 (1), 692 (2021).

- de Morree, A., et al. Staufen1 inhibits MyoD translation to actively maintain muscle stem cell quiescence. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 114 (43), E8996-E9005 (2017).

- Luo, D., et al. Deltex2 represses MyoD expression and inhibits myogenic differentiation by acting as a negative regulator of Jmjd1c. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 114 (15), E3071-E3080 (2017).

- Wersto, R. P., et al. Doublet discrimination in DNA cell-cycle analysis. Cytometry. 46 (5), 296-306 (2001).

- Porpiglia, E., Blau, H. M. Plasticity of muscle stem cells in homeostasis and aging. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 77, 101999 (2022).

- Porpiglia, E., et al. Elevated CD47 is a hallmark of dysfunctional aged muscle stem cells that can be targeted to augment regeneration. Cell Stem Cell. 29 (12), 1653-1668 (2022).

- Brunet, A., Goodell, M. A., Rando, T. A. Ageing and rejuvenation of tissue stem cells and their niches. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 24 (1), 45-62 (2022).

- Danielli, S. G., et al. Single-cell profiling of alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma reveals RAS pathway inhibitors as cell-fate hijackers with therapeutic relevance. Sci Adv. 9 (6), (2023).

- de Morree, A., Rando, T. A. Regulation of adult stem cell quiescence and its functions in the maintenance of tissue integrity. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 24 (5), 334-354 (2023).

- Yucel, N., et al. Glucose metabolism drives histone acetylation landscape transitions that dictate muscle stem cell glucose metabolism drives histone acetylation landscape transitions that dictate muscle stem cell function. Cell Rep. 27 (13), 3939-3955 (2019).

- Tierney, M. T., Sacco, A. Inducing and evaluating skeletal muscle injury by notexin and barium chloride. Methods Mol Biol. 1460, 53-60 (2016).

- Hardy, D., et al. Comparative study of injury models for studying muscle regeneration in mice. PLoS One. 11 (1), (2016).

- Call, J. A., Lowe, D. A. Eccentric contraction-induced muscle injury: Reproducible, quantitative, physiological models to impair skeletal muscle's capacity to generate force. Methods Mol Biol. 1460, 3-18 (2016).

- Garry, G. A., Antony, M. L., Garry, D. J. Cardiotoxin Induced Injury and Skeletal Muscle Regeneration. Methods Mol Biol. 1460, 61-71 (2016).

- Le, G., Kyba Lowe, D. A., M, Freeze injury of the tibialis anterior muscle. Methods Mol Biol. 1460, 33-41 (2016).

- Borok, M., et al. Progressive and coordinated mobilization of the skeletal muscle niche throughout tissue repair revealed by single-cell proteomic analysis. Cells. 10 (4), (2021).

- Petrilli, L. L., et al. High-dimensional single-cell quantitative profiling of skeletal muscle cell population dynamics during regeneration. Cells. 9 (7), 1723 (2020).

- Giordani, L., et al. High-dimensional single-cell cartography reveals novel skeletal muscle-resident cell populations. Mol Cell. 74 (3), 609-621 (2019).

- Hartmann, F. J., et al. Scalable conjugation and characterization of immunoglobulins with stable mass isotope reporters for single-cell mass cytometry analysis. Methods Mol Biol. , 55-81 (1989).

- Frimand, Z., Das Barman, ., Kjær, S., R, T., Porpiglia, E., de Morrée, A. Isolation of quiescent stem cell populations from individual skeletal muscles. J Vis Exp. 190, 64557 (2022).

- Krutzik, P. O., Nolan, G. P. Intracellular phospho-protein staining techniques for flow cytometry: monitoring single cell signaling events. Cytometry A. 55 (2), 61-70 (2003).

- Bodenmiller, B., et al. Multiplexed mass cytometry profiling of cellular states perturbed by small-molecule regulators. Nat Biotechnol. 30 (9), 858-867 (2012).

- Schulz, K. R., Danna, E. A., Krutzik, P. O., Nolan, G. P. Single-cell phospho-protein analysis by flow cytometry. Curr Protoc Immunol. Chapter. 8, 11-18 (2012).

- Krutzik, P. O., Clutter, M. R., Nolan, G. P. Coordinate analysis of murine immune cell surface markers and intracellular phosphoproteins by flow cytometry. J Immunol. 175 (4), 2357-2365 (2005).

- Krutzik, P. O., Irish, J. M., Nolan, G. P., Perez, O. D. Analysis of protein phosphorylation and cellular signaling events by flow cytometry: techniques and clinical applications. Clin Immunol. 110 (3), 206-221 (2004).

- Han, G., Spitzer, M. H., Bendall, S. C., Fantl, W. J., Nolan, G. P. Metal-isotope-tagged monoclonal antibodies for high-dimensional mass cytometry. Nat Protoc. 13 (10), 2121-2148 (2018).

- Chevrier, S., et al. Compensation of signal spillover in suspension and imaging mass cytometry. Cell Syst. 6 (5), 612-620 (2018).

- Bjornson, Z. B., Nolan, G. P., Fantl, W. J. Single-cell mass cytometry for analysis of immune system functional states. Curr Opin Immunol. 25 (4), 484-494 (2013).

- Kalina, T., Lundsten, K., Engel, P. Relevance of antibody validation for flow cytometry. Cytometry A. 97 (2), 126-136 (2020).

- Baumgarth, N., Roederer, M. A practical approach to multicolor flow cytometry for immunophenotyping. J Immunol Methods. 243 (1-2), 77-97 (2000).

- Roederer, M. Spectral compensation for flow cytometry: visualization artifacts, limitations, and caveats. Cytometry. 45 (3), 194-205 (2001).

- Tung, J. W., Parks, D. R., Moore, W. A., Herzenberg, L. A., Herzenberg, L. A. New approaches to fluorescence compensation and visualization of FACS data. Clin Immunol. 110 (3), 277-283 (2004).

- Cossarizza, A., et al. Guidelines for the use of flow cytometry and cell sorting in immunological studies (third edition). Eur J Immunol. 51 (12), 2708-3145 (2021).

转载和许可

请求许可使用此 JoVE 文章的文本或图形

请求许可探索更多文章

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

版权所属 © 2025 MyJoVE 公司版权所有,本公司不涉及任何医疗业务和医疗服务。