Se requiere una suscripción a JoVE para ver este contenido. Inicie sesión o comience su prueba gratuita.

Method Article

Protocolo para la evaluación de los efectos relativos de medio ambiente y la genética en el asta y el crecimiento del cuerpo para una larga vida cérvidos

En este artículo

Resumen

Diferencias fenotípicas entre las poblaciones de cérvidos pueden estar relacionados con genética de la población o nutrición; discerniendo que es difícil en la naturaleza. Este protocolo describe cómo se diseñó un estudio controlado donde se eliminó la variación nutricional. Encontramos que variación fenotípica de venado de cola blanca del hombre más fue limitado por la nutrición que genética.

Resumen

Fenotipo de cérvidos puede colocarse en una de dos categorías: eficacia, que promueve la supervivencia crecimiento morfométrico extravagantes y lujo, que promueve el crecimiento del cuerpo y armas de gran tamaño. Las poblaciones de una misma especie muestran cada fenotipo dependiendo de las condiciones ambientales. Aunque tamaño cuerno y cuerpo de hombre venado cola blanca (Odocoileus virginianus) varía según la región fisiográfica en Mississippi, Estados Unidos y esta fuertemente correlacionado con la variación regional en calidad nutricional, los efectos de la genética de población de las poblaciones nativas y los esfuerzos de re-stocking anteriores no pueden tenerse en cuenta. Este protocolo describe cómo se diseñó un estudio controlado, donde se controlan otros factores que influyen en el fenotipo, como la edad y la nutrición. Llevamos capturados hembras y cervatillos de seis meses de tres regiones fisiográficas distintas en Mississippi, Estados Unidos a la Mississippi estado oxidado Dawkins Memorial ciervos unidad de la Universidad. Ciervos de la misma región fueron criados para producir una segunda generación de crías, lo que nos permite evaluar las respuestas generacionales y efectos maternos. Ciervos de todos comieron la misma calidad (20% de proteína cruda ciervos de la pelotilla) dieta ad libitum. Únicamente había marcado a cada recién nacido y registrado pie de masa, traseras de cuerpo y longitud de cuerpo total. Cada caída posterior, sedado personas mediante inyección remota y muestra el mismo morfometría plus las cornamentas de los adultos. Se encontró que todos morfometría aumentó en tamaño de primera a segunda generación, con compensación total de tamaño de la cornamenta (variación regional no presente) y una compensación parcial de la masa del cuerpo (algunas pruebas de variación regional) evidente en la segunda generación. Segunda generación de machos que originaron de la peor calidad suelo región muestra un aumento de 40% en el tamaño de la cornamenta y un aumento de 25% en la masa corporal en comparación con sus contrapartes silvestres cosechadas. Nuestros resultados sugieren que la variación fenotípica de salvaje macho venado cola blanca en Mississippi están más relacionados con las diferencias en calidad nutricional que la genética de la población.

Introducción

Factores ambientales, que experiencias de una madre durante la gestación y la lactancia pueden influir en fenotipo de su descendencia, independiente del genotipo1,2,3. Las madres que habitan en ambientes de alta calidad probablemente producirá crías que presentan un fenotipo de lujo (gran cornamenta y cuerpo tamaño4), mientras que las madres que habitan en un entorno de baja calidad pueden producir crías que presentan un fenotipo de eficiencia (pequeños cuernos y cuerpo tamaño4). Por lo tanto, persistir en un entorno de alta calidad puede permitir que una madre producir descendencia masculina con grandes características fenotípicas, que pueden influir directamente en oportunidades reproductivas5,6,7,8 de la descendencia e indirectamente influir en la aptitud inclusiva de la madre.

Aunque la nutrición influye directamente en las características fenotípicas a través de taxa (americanus de Ursus, arctos de Ursus9; FuscusI Mackloti 10; Larus michahellis 11), varios factores pueden afectar fenotipos de venado cola blanca en Mississippi, Estados Unidos. Tamaño de la cornamenta y el cuerpo son un tercio más grande para algunas poblaciones en comparación con otros12. Esta variación se correlaciona fuertemente con forraje calidad13,14; los machos más grandes se encuentran en áreas con la mayor calidad de forraje. Sin embargo, los esfuerzos de restauración histórica de venado cola blanca en Mississippi puedan haber llevado a los cuellos de botella genéticos o fundador efectos15,16, que puede explicar también parte de la variación regional observada en fenotipo de venado cola blanca.

Proporcionamos el protocolo que utilizamos para el control de calidad nutricional de los capturados venado cola blanca, que nos permitió evaluar si fenotipo masculino está limitada por la genética de la población. Este protocolo también nos permitió evaluar si quedando efectos maternos estaban presentes en nuestras poblaciones. Nuestro diseño controlado es preferente a los estudios realizados en poblaciones que van gratis, que se limitan a usar las variables ambientales como un proxy para restricción nutricional3,17. Nuestro diseño controlado permite también otras variables como potencial crónico estrés social relacionados con interacciones a mantenerse constante todos los individuos son sometidos a viviendas similares y las prácticas de cría. Además, porque la nutrición influye directamente en otros aspectos de la historia de la vida desde reproducción hasta supervivencia18,19, control de la nutrición permite investigadores evaluar otras variables que afectan aspectos de la historia de la vida mamífera. Protocolos similares se han descrito para evaluar cuestiones relacionadas con aspectos de la historia de la vida de otros ungulados en América del norte (e.g., 20,21).

Protocolo

Ethics Statement: The Mississippi State University Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee approved all capture, handling, and marking techniques under protocols 04-068, 07-036, 10-033 and 13-034.

1. Establish Capture Sites, Immobilize and Transport wild White-tailed Deer

- Identify public and private properties that are enrolled in the Deer Management Assistance Program22 and establish ≥29 capture sites throughout three source regions in Mississippi, USA.

- Identify several capture locations within each source region to ensure that the range of genetic variation present in the regional population is captured.

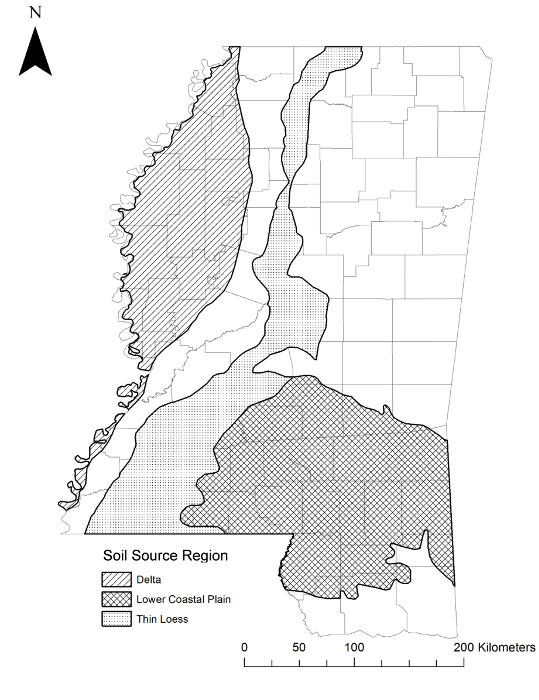

- Note: Here, source regions included the Delta, which comprises almost 17% of total land area in Mississippi, USA, and is considered a high-quality soil region with agriculture as the primary land use23,24. All study animals were captured from this region within the distribution of O. v. virginianus25. Other regions included the Thin Loess region (upper and lower Thin Loess combined), which comprises almost 14% of total land area in Mississippi, USA and is considered a medium quality soil region. Agriculture is also a primary land use in the Thin Loess region, though not as prevalent as in the Delta23,24. All study animals were captured from this region within the distribution of O. v. virginianus21. Lastly, the Lower Coastal Plain (LCP) soil region comprises nearly 22% of Mississippi and is classified as a low quality soil region. Primary land uses in the LCP are pine timber production and livestock grazing23,24. The LCP also overlaps the geographical distribution of O. v. osceola; four of the six source populations were within 21 km of this distribution25. This subspecies was described as smaller than O. v. virginianus26.

Figure 1: Source Populations. Physiographic regions where pregnant dams and fawns were caught in Mississippi, USA. This figure has been modified from reference31. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

- Select potential capture sites that meet the following criteria; habitat characteristics conducive to deer movement, proximity to roads for access, and distribution across the study area.

NOTE: Capture sites must allow for concealment of the capture technician.- Bait sites with about 10 kg of shelled corn to entice deer to visit and evaluate use based on bait consumption and deer photographed by motion-sensitive cameras. Relocate to alternate sites if deer do not attend baited sites within 5-7 days.

- During capture events, sit in a concealed "stand."

- Place stand about 20 m downwind from the bait pile, taking the prevailing wind direction into consideration so that deer approaching the bait are less able to smell the capture technician.

NOTE: Elevated stands are strongly preferred, and safety harnesses are required. There are several variations of stands with a variety of commercial sources and use varies by personal preference. For example, a lock-on stand would include seating with a ladder for access attached to a tree with straps. Portable climbing stands can be carried in by the capture technician and allow for increased mobility as the technician can choose a specific tree once they arrive at the capture site. Portable climbing stands are limited to use in straight trees without branches up the chosen height.

- Place stand about 20 m downwind from the bait pile, taking the prevailing wind direction into consideration so that deer approaching the bait are less able to smell the capture technician.

- Use a dart gun coupled with a 3 cc radio-telemetry dart to deliver a mixture of teletamine HCl (4.4 mg/kg) and xylazine HCl (2.2 mg/kg).

- Schedule capture efforts to coincide with the typical crepuscular activity cycle of deer27. Begin each capture attempt 2-3 h prior to sunset.

- Continue capture events for 2-3 h after sunset using night-vision goggles and a red dot laser for shot placement if deer are not captured during daylight hours.

- Take shots at deer when they are broadside and stationary.

NOTE: The hind quarter of the deer is the target because it has significant muscle tissue and is located away from the heart and lungs. - Wait about 15 min for darted target animals (six-month-old fawns of either sex or pregnant adult females) to become fully immobilized before locating it with directional radio-telemetry equipment.

- Confirm individuals are sedated by checking for eye reflexes (blinking). Then apply ophthalmic ointment to the eyes and blindfold deer to reduce stress.

NOTE: Loss of thermoregulation is a consequence of immobilization. - Use a rectal thermometer to assess body temperature after recovery. Warm deer with heated blankets if the animal's temperature is below 37.7 °C. Cool deer with ice packs if the animal's temperature is above 40.0 °C.

- Place deer in a sternal position on a military style gurney and transport deer from the capture location to an enclosed trailer.

- After placing the deer into the trailer, reverse the effects of xylazine HCl with 0.125 mg/kg yohimbine HCl28.

- Transport all captured deer to the desired captive facility (e.g., Mississippi State University Rusty Dawkins Memorial Deer Unit; MSU Deer Unit) and keep them separated by source region.

2. Captive Facilities and General Husbandry Practices of Research Animals

NOTE: The MSU Deer Unit is subdivided into five 0.4 to 0.8 ha pens.

- Cover every side of each pen with shade cloth to act as a visual and physical barrier between pens. Shade cloth helps reduce injuries and provides shade during summer months.

- Place 1-2 elevated box blinds at one end of each pen to facilitate darting events during data collection.

- Place two trough style feeders at separate ends of each pen to reduce competition for food among deer. Also provide a water trough in each pen.

- Provide deer with a high-quality diet (20% crude protein deer pellets) ad libitum.

NOTE: Here, additional available forages within pens included (Trifolium spp) and fescue (Festuca spp) along with volunteer grasses and forbs. - If present, maintain available forages within pens using a mixture of herbicides to control broadleaf weeds and grasses using mixture rates found on respective labels.

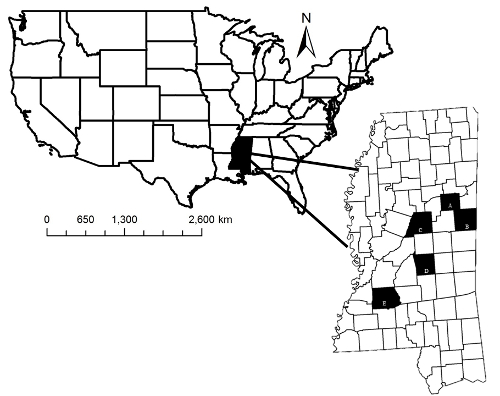

NOTE: Using off-campus facilities to house ≥5.5 month old males will likely be needed. These facilities consisted of two 0.7 ha pens on each of three properties with husbandry practices similar to the MSU Deer Unit.

Figure 2: Captive Facility Locations. Study area where satellite facilities and the Mississippi State University (MSU) Deer Unit were located. Shaded areas indicate Oktibbeha (A), Noxubee (B), Attala (C), Scott (D), and Copiah (E), counties, Mississippi, USA.This figure has been modified from reference34. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

3. Parasite and Disease Control

- Monitor research animals for roundworm parasites (Strongyloides spp) using fecal floatation with parasites measured as eggs per gram (EPG).

- If present at high levels, provide parasite control by administering a pelleted wormer (active ingredient fenbendazole) at a rate of about 0.77 kg of pelleted wormer per 22.7 kg of feed during the month of May.

- If parasite levels remain high after initial treatment, use an ivermectin pour-on treatment (5 mg/mL)29, mixed at a rate of 2 mL/0.45 kg and administer to animals at a rate of 0.45 kg of treated feed per 45.4 kg of animal mass.

NOTE: Epizootic hemorrhagic disease is sometimes lethal viral disease spread by a biting midge (Culicoides spp) during summer and fall months. If present, treat the research facility with insecticide (5% ultra-low volume insecticide) 2-3 times per week from July 1 to October 1 to decrease prevalence of the vectors among research animals. Spray this insecticide within each pen and around the perimeter of the facility about 90 min before official sunset via fogger. Preferred methods to control for parasites and diseases are unique to each captive facility. Veterinarians must be consulted during any captive wildlife research to ensure animal health and safety.

4. Data Collection

Figure 3: Data Collection of Newborn Fawns. Measuring hind foot length from a new born fawn at the Mississippi State University Rusty Dawkins Memorial Deer Unit in Oktibbeha County, Mississippi, USA. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

- Search the captive facility daily for fawns during the parturition season.

- Uniquely mark newborn fawns with medium plastic ear tags using an ear tagger with antibiotic applied to the male end of the tag to prevent potential infection. Place ear tag about the center of the fawn's ear.

- Measure body mass (nearest 0.01 kg) with a digital hanging scale and measure hind foot length and total body length (nearest mm).

- Collect hair samples and send them to a remote site for parentage assignment (see the Table of Materials).

NOTE: Parentage assignment was made using DNA based on a proprietary, non-statistical custom structured query language database. In the pairwise allele comparison, the remote parentage assignment site assigned parentage when they excluded all but one sire and one dam based upon a shared allele from each parent at all loci tested (B. G. Cassidy, personal communication). This method of parentage assignment was also used in previous research conducted on captive white-tailed deer30,31. - Administer 2 cc of Clostridium perfringens types C and D toxoid and Clostridium perfringens types C and D antitoxin subcutaneously and administer 0.3 cc/kg of ivermectin in propylene glycol (Mississippi State University Veterinarian School, Mississippi, USA) orally to each fawn.

- Chemically immobilize adult males (≥1.5 years-old) during October and November for data collection.

- Immobilize penned adults using the same combination of teletamine HCl and xylazine HCl used for capture of wild animals (step 1.4).

- During sedation events, walk the technician who will be darting to the end of the pen where the elevated blinds are located. Have a single technician in each of two blinds.

- Have the individual who walked the technician to the blind walk back to the opposite end of the pen.

NOTE: Deer move away from these technicians and locate themselves in front of the blinds where technicians are in position to take ethical shots on each deer. - Take shots at deer when they are broadside and stationary (section 1.4).

- Wait about 15 min for darted animals to become fully immobilized before approaching it.

- Confirm individuals are sedated by checking for eye reflexes (blinking). Apply ophthalmic ointment to the eyes and blindfold deer to reduce stress.

- After the darters successfully sedate an individual deer, monitor the deer's vital rates.

- Use a rectal thermometer to assess body temperature after recovery. Warm deer with heated blankets if the animal's temperature is below 37.7 °C. Cool deer with ice packs if the animal's temperature is above 40.0 °C.

- Load the deer on a military-style gurney, and transport it via utility task vehicle to a predetermined data collection area.

- Once transported, record the same morphometric measurements recorded at birth (step 4.1).

- Measure body mass (nearest 0.01 kg) with a digital hanging scale and measure hind foot length and total body length (nearest mm).

NOTE: Individual deer react differently to the combination of drugs used during sedation events so administer about 0.1-0.3 cc of the teletamine HCl and xylazine HCl mixture (depending on body mass of an individual deer) if an individual comes out of sedation before data collection is completed.

- Measure body mass (nearest 0.01 kg) with a digital hanging scale and measure hind foot length and total body length (nearest mm).

- Administer size-appropriate amounts of antibiotic, ivermectin, a clostidrial vaccine, and a leptospirosis vaccine to all deer after they are transported to the data collection area (see sections 1 and 3).

- Take three antler measurements from adult males using an antler measuring tape while the animal is sedated.

- Measure the inside spread (widest distance between main beams), basal circumference (smallest diameter located between the burr and G1 tine), and main beam length (distance from antler base to the tip of the main beam) of antlers prior to antler removal.

- Remove antlers about 3 cm above the burr using a reciprocating saw. Do not remove antlers less than 3 cm.

Figure 4: Data Collection of Adult Males. Antler removal via reciprocating saw from a captive adult male white-tailed deer. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

- After all data is collected from the sedated individual, place the deer into the appropriate pen and administer either 0.125 mg/kg yohimbine HCl28 or 4.0 mg/kg tolazoline HCl32 to reverse the effects of xylazine HCl. Monitor individuals to ensure they remain in a sternal position until they come out of sedation and are fully alert.

NOTE: If complications occur and animals must be euthanized, then euthanasia by cerebral dislocation via bolt stunner and severing of the jugular vein are ethical means to dispatch the animal. - Bring the antlers to a designated area to finish measuring antler size.

- Measure each individual tine protruding from the main beam (G1, G2, G3, etc.) and additional abnormal points by aid of wire.

NOTE: Points that do not have a matching counterpart on the opposite main beam or are not consistent with the definition of a typical antler set are defined by the Boone and Crockett Club33. - Wrap the wire around where the tine intersects the main beam and mark that point for reference.

- Measure from this reference point to the tip of the tine and repeat for each tine.

- Collect remaining circumference measurements by identifying the smallest point between the G1 and G2 tines (H2 circumference), the G2 and G3 tines (H3 circumference), and the G3 and G4 tine if present (H4 circumference).

- If the G4 tine is not present, measure the distance between the midpoint of the G3 tine and the end of the main beam and measure the H4 circumference at the midway point.

- Measure less than four circumferences when antlers contain less than three tines.

NOTE: For example, a main beam with two typical points include only three circumference measurements. Individuals may use other guidelines (Safari Club International) for calculating antler size; however, consistent methods must be used for each animal for valid comparison. - After making all measurements, calculate an antler score similar to the gross nontypical Boone and Crockett score33.

- Weigh antlers to the nearest 0.1 g using a scientific digital scale and assign a minimal critical antler mass of 1 g for first-year animals with antlers shorter than 3 cm.

- Measure each individual tine protruding from the main beam (G1, G2, G3, etc.) and additional abnormal points by aid of wire.

- Chemically immobilize penned juveniles at approximately 5.5 months of age using the same methods for adults (section 4.2) and mark juveniles with a large plastic ear tag (step 4.1.1).

- Use the same drug mixture rates to immobilize captive adults as used for immobilizing wild deer (section 1).

- Collect the same measurements collected at birth (step 4.1.2) and administer the same prophylactics as adults (section 4.2).

NOTE: After all data is collected, transport each juvenile male to its randomly assigned satellite facility via trailer.

5. Producing First- and Second-generation Offspring

- Classify six-month-old wild-caught fawns and offspring born at the captive facility from wild-caught mothers as first-generation individuals.

- During the breeding season, place two males with 7-16 females for an average breeding sex ratio of one male to eight females.

NOTE: Select breeding males from satellite facilities based on physical appearance, because the healthiest males (largest antlers and body size) are most likely to service females for the entirety of the breeding season without suffering from injury due to the aggressive nature of males during the breeding season.- Only allow deer to breed with other individuals from the same source region (e.g., Delta males breed Delta females, Thin Loess males breed Thin Loess females, and LCP males breed LCP males).

- Classify deer conceived by first-generation parents as second-generation offspring. Raise these individuals in captivity from birth and feed the same high-quality diet as their parents.

NOTE: Females may produce offspring multiple years but typically with different sires each year. Collect the same data on second-generation offspring as collected on first-generation and wild-caught individuals.

Resultados

Individual edad, calidad nutricional y genética influyen en fenotipo macho venado de cola blanca. Nuestro diseño del estudio permitió controlar la calidad de los ciervos de nutrición estaban consumiendo y nos permitió identificar la edad de cada ciervo para comparaciones válidas dentro de clases del año. Controlando la nutrición y la edad con nuestro estudio de diseño, mejor pudimos entender si población genética fueron restringiendo el fenotipo de los machos de las poblaciones...

Discusión

Hay varios pasos asociados con nuestro protocolo; sin embargo, hay cuatro pasos críticos que deben tomarse para asegurar el éxito con este protocolo. En primer lugar, durante la captura de ciervos salvajes, debe haber varios lugares de captura a lo largo de una región de la fuente (paso 1.1.1). Tener varias ubicaciones captura asegura que cualquier variabilidad genética asociada a la región de la fuente se representará entre ciervos. En segundo lugar, los ciervos deben mantenerse separados por región de origen dur...

Divulgaciones

Los autores no tienen nada que revelar.

Agradecimientos

Agradecemos al Departamento de Mississippi de la vida silvestre, pesca y parques (MDWFP) apoyo financiero con recursos de la ayuda Federal en la ley de restauración de vida silvestre (W-48-61). Agradecemos a biólogos MDWFP W. McKinley, A. Blaylock, Gary A. y L. Wilf por su amplia participación en la recolección de datos. También agradecemos a S. Tucker como Coordinador de instalaciones y varios estudiantes graduados y técnicos por su ayuda para recogida de datos. Este manuscrito es contribución WFA427 del bosque de la Universidad Estatal de Mississippi y centro de investigación de vida silvestre.

Materiales

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Shelled Corn | |||

| Elevated Stand | |||

| Safety Harness | |||

| Ground Blind | |||

| Model 196 Projector | Pneu-Dart, Pennsylvania, USA | ||

| 3cc Radio-Telemetry Darts | (Pneu-Dart, Pennsylvania, USA) | ||

| Various Sized Darts | (Pneu-Dart, Pennsylvania, USA) | ||

| Teletamine HCl | (Telazol, Fort Dodge Animal Health, Iowa, USA) | ||

| Xylazine HCl | (West Texas Rx Pharmacy, Amarillo, Texas, USA) | ||

| Yhoimbine HCl | |||

| Tolazoline HCl | |||

| Military Style Gurney | |||

| Rectal Thermometer | |||

| Shade Cloth | |||

| 20% Crude Protein Deer Pellets | (Purina AntlerMax Professional High Energy Breeder 59UB, Purina, Missouri, USA) | ||

| Trough Style Feeders | |||

| Commercial Clover | (Durana Clover, Pennington Seed Co., Georgia, USA) | ||

| Commercial Fescue | (Max-Q Fescue, Pennington Seed Co., Georgia, USA) | ||

| Blankets | |||

| Ice Packs | |||

| Broadleaf Weed Control (2, 4-DB Herbacide, Butyrac 200) | |||

| Grass Control | (Poast Herbacide, BASF Co.) | ||

| Pelleted Wormer | Safeguard Co., | active ingredient fenbendazole | |

| Parasite Pour-on Treatment | (Ivomec, Merial Co.) | ||

| Insecticide | Riptide, McLaughlin Gormley King Co.) | ||

| Medium and Large Plastic Ear Tags | (Allflex, Texas, USA) | ||

| Remote site that assigned parentage | DNA Solutions Animal Solutions Manager (DNA Solutions, Oklahoma, USA) | ||

| Digital Hanging Scale | (Moultrie, EBSCO Industries, Inc.) | ||

| Tape Measure | |||

| Clostridium Perfringens Types C and D Toxoid Essential 3 | (Colorado Serum Co.) | ||

| Clostridium Perfringens Types C and D Antitoxin Equine Origin | (Colorado Serum Co.) | ||

| Ivermectin in propylene glycol | |||

| Antibiotic | (Nuflor, Schuering-Plough Animal Health Corp., New Jersey, USA) | ||

| Ivermectin | (Norbrook Labratories, LTD., Down, Northern Ireland, UK) | ||

| Clostidrial vaccine | (Vision 7 with SPUR, Ivesco LLC, Iowa, USA) | ||

| Leptospirosis vaccine | (Leptoferm-5, Pfizer, Inc., New York, USA) | ||

| Trailer for transport | |||

| Reciprocating saw | (DEWALT, Maryland, USA) | ||

| Scientific Digital Scale | (Global Industrail, Global Equipment Company Inc) | ||

| Antler Measuring Tape | |||

| Fogger | |||

| Plastic Ear Tags | (Allflex, Texas, USA) | ||

| Plastic Ear Tagger | (Allflex, Texas, USA) |

Referencias

- Bernardo, J. Maternal effects in animal ecology. Amer Zool. 36 (2), 83-105 (1996).

- Forchhammer, M. C., Clutton-Brock, T. H., Lindstrom, J., Albon, S. D. Climate andpopulation density induce long-term cohort variation in a northern ungulate. J Anim Ecol. 70 (5), 721-729 (2001).

- Freeman, E. D., Larsen, R. T., Clegg, K., McMillan, B. R. Long-lasting effects of maternal condition in free-ranging cervids. PLoS ONE. 8 (3), 5873 (2013).

- Geist, V., Burton, M. N. Environmentally guided phenotype plasticity in mammals and some of its consequences to theoretical and applied biology. Alternative life-history styles of animals. , 153-176 (1989).

- Clutton-Brock, T. H., Guinness, F. E., Albon, S. D. Reproductive success in stags. Red Deer: Behavior and ecology of two sexes. , 151-152 (1982).

- Coltman, D. W., Festa-Bianchet, M., Jorgenson, J. T., Strobeck, C. Age-dependent sexual selection in bighorn rams. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 269 (1487), 165-172 (2002).

- Festa-Bianchet, M. The cost of trying: Weak interspecific correlations among life-history components in male ungulates. Can J Zool. 90 (9), 1072-1085 (2012).

- Kie, J. G., et al. Reproduction in North American elk Cervus elaphus.: Paternity of calves sired by males of mixed age classes. Wildlife Biol. 19 (3), 302-310 (2013).

- Welch, C. A., Keay, J., Kendall, K. C., Robbins, C. T. Constraints on frugivory by bears. Ecology. 78 (4), 1105-1119 (1997).

- Madsen, T., Shine, R. Silver spoons and snake body sizes: Prey availability early in life influences long-term growth rates of free-ranging pythons. J Anim Ecol. 69 (6), 952-958 (2000).

- Saino, N., Romano, M., Rubolini, D., Caprioli, M., Ambrosini, R., Fasola, M. Food supplementation affects egg albumen content and body size asymmetry among yellow-legged gull siblings. Behav Ecol Sociobiol. 64 (11), 1813-1821 (2010).

- Strickland, B. K., Demarais, S. Age and regional differences in antlers and mass of white-tailed deer. J Wildl Manage. 64 (4), 903-911 (2000).

- Jones, P. D., Demarais, S., Strickland, B. K., Edwards, S. L. Soil region effects on white-tailed deer forage protein content. Southeast Nat. 7 (4), 595-606 (2008).

- Strickland, B. K., Demarais, S. Influence of landscape composition and structure on antler size of white-tailed deer. J Wildl Manage. 72 (5), 1101-1108 (2008).

- DeYoung, R. W., Demarais, S., Honeycutt, R. L., Rooney, A. P., Gonzales, R. A., Gee, K. L. Genetic consequences of white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) restoration in Mississippi. Mol Ecol. 12 (12), 3237-3252 (2003).

- Sumners, J. A., et al. Variable breeding dates among populations of white-tailed deer in the southern United States: The legacy of restocking. J Wildl Manage. 79 (8), 1213-1225 (2015).

- Mech, D. L., Nelson, M. E., McRoberts, R. E. Effects of maternal and grandmaternal nutrition on deer mass and vulnerability to wolf predation. J Mammal. 72 (1), 146-151 (1991).

- Therrien, J. F., Còtê, S., Festa-Bianchet, D. M., Ouellet, J. P. Maternal care in white-tailed deer: trade-off between maintenance and reproduction under food restriction. Anim Behav. 75 (1), 235-243 (2008).

- Parker, K. L., Barboza, P. S., Gillingham, M. P. Nutrition integrates environmental responses of ungulates. Funct Ecol. 23 (1), 57-69 (2009).

- Monteith, K. L., Schmitz, L. E., Jenks, J. A., Delger, J. A., Bowyer, R. T. Growth of male white-tailed deer: consequences of maternal effects. J Mammal. 90 (3), 651-660 (2009).

- Tollefson, T. N., Shipley, L. A., Myers, W. L., Keisler, D. H., Nairanjana, D. Influence of summer and autumn nutrition on body condition and reproduction in lactating mule deer. J Wildl Manage. 74 (5), 974-986 (2010).

- Guynn, D. C., Mott, S. P., Cotton, W. D., Jacobson, H. A. Cooperative management of white-tailed deer on private lands in Mississippi. Wildl Soc Bull. 11 (3), 211-214 (1983).

- Pettry, D. E. Soil resource areas of Mississippi. Mississippi Agricultural and Forestry Experiment Station. , (1977).

- Snipes, C. E., Nichols, S. P., Poston, D. H., Walker, T. W., Evans, L. P., Robinson, H. R. Current agricultural practices of the Mississippi Delta. Office of Agricultural Communications. , (2005).

- Baker, R. H., Halls, L. K. Origin, classification, and distribution of the white-tailed deer. White-tailed deer: ecology and management. , 1-18 (1984).

- Barbour, T., Allen, G. M. The white-tailed deer of eastern United States). J Mammal. 3 (2), 65-80 (1922).

- Rouleau, I., Crête, M., Ouellet, J. P. Contrasting the summer ecology of white-taileddeer inhabiting a forested and an agricultural landscape. Ecoscience. 9 (4), 459-469 (2002).

- Kreeger, T. J. . Handbook of wildlife chemical immobilization. , (1996).

- Pound, J. M., Miller, J. A., Oethler, D. D. Depletion rates of injected and ingested Ivermectin from blood serum of penned white-tailed deer, Odocoileus virginianus (Zimmermann) (Artiodactyla: Cervidae). J Medl Entomol. 41 (1), 65-68 (2004).

- Jones, P. D., Demarais, S., Strickland, B. K., DeYoung, R. W. Inconsistent relation of male body mass with breeding success in captive white-tailed deer. J Mammal. 92 (3), 527-533 (2011).

- Michel, E. S., Flinn, E. B., Demarais, S., Strickland, B. K., Wang, G., Dacus, C. M. Improved nutrition cues switch from efficiency to luxury phenotypes for a long-lived ungulate. Ecol Evol. 6 (20), 7276-7285 (2016).

- Miller, B. F., Muller, L. I., Doherty, T., Osborn, D. A., Miller, K. V., Warren, R. J. Effectiveness of antagonists for tiletamine-zolazepam/xylazine immobilization in female white-tailed deer. J Wildl Dis. 40 (3), 533-537 (2004).

- Nesbitt, W. H., Wright, P. L., Buckner, E. L., Byers, C. R., Reneau, J. . Measuring and scoring North American big game trophies. 3rd edn. , (2009).

- Michel, E. S., Demarais, S., Strickland, B. K., Smith, T., Dacus, C. M. Antler characteristics are highly heritable but influenced by maternal factors. J Wildl Manage. 80 (8), 1420-1426 (2016).

- Severinghaus, C. W. Tooth development and wear as criteria of age in white-tailed deer. J Wildl Manage. 13 (2), 195-216 (1949).

- Gee, K. L., Webb, S. L., Holman, J. H. Accuracy and implications of visually estimating age of male white-tailed deer using physical characteristics from photographs. Wild Soc Bull. 38, 96-102 (2014).

- Storm, D. J., Samuel, M. D., Rolley, R. E., Beissel, T., Richards, B. J., Van Deelen, T. R. Estimating ages of white-tailed deer: Age and sex patterns of error using tooth wear-and-replacement and consistency of cementum annuli. Wild Soc Bull. 38 (1), 849-865 (2014).

- Montero, D., Izquierdo, M. S., Tort, L., Robaina, L., Vergara, J. M. High stocking density produces crowding stress altering some physiological and biochemical parameters in gilthead seabream, Sparus aurata., juveniles. Fish Physiol Biochem. 20 (1), 53-60 (1999).

- Charbonnel, N., et al. Stress demographic decline: a potential effect mediated by impairment of reproduction and immune function in cyclic vole populations. Physiol Biochem Zool. 81 (1), 63-73 (2008).

- Crews, D., Gillette, R., Scarpino, S. V., Manikkam, M., Savenkova, M. I., Skinner, M. K. Epigenetic transgenerational inheritance of altered stress responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 109 (23), 9143-9148 (2012).

- Maher, J. M., Werner, E. E., Denver, R. J. Stress hormones mediate predator-induced phenotypic plasticity in amphibian tadpoles. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 280 (1758), 20123075 (2013).

Reimpresiones y Permisos

Solicitar permiso para reutilizar el texto o las figuras de este JoVE artículos

Solicitar permisoThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

ACERCA DE JoVE

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. Todos los derechos reservados