A subscription to JoVE is required to view this content. Sign in or start your free trial.

Method Article

Preparation, Purification, and Characterization of Lanthanide Complexes for Use as Contrast Agents for Magnetic Resonance Imaging

In This Article

Summary

We demonstrate the metalation, purification, and characterization of lanthanide complexes. The complexes described here can be conjugated to macromolecules to enable tracking of these molecules using magnetic resonance imaging.

Abstract

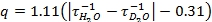

Polyaminopolycarboxylate-based ligands are commonly used to chelate lanthanide ions, and the resulting complexes are useful as contrast agents for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Many commercially available ligands are especially useful because they contain functional groups that allow for fast, high-purity, and high-yielding conjugation to macromolecules and biomolecules via amine-reactive activated esters and isothiocyanate groups or thiol-reactive maleimides. While metalation of these ligands is considered common knowledge in the field of bioconjugation chemistry, subtle differences in metalation procedures must be taken into account when selecting metal starting materials. Furthermore, multiple options for purification and characterization exist, and selection of the most effective procedure partially depends on the selection of starting materials. These subtle differences are often neglected in published protocols. Here, our goal is to demonstrate common methods for metalation, purification, and characterization of lanthanide complexes that can be used as contrast agents for MRI (Figure 1). We expect that this publication will enable biomedical scientists to incorporate lanthanide complexation reactions into their repertoire of commonly used reactions by easing the selection of starting materials and purification methods.

Protocol

1. Metalation using LnCl3 salts

- Dissolve the ligand in water to produce a solution of 30-265 mM. The ligand 2-(4-isothiocyanatobenzyl)-diethylenetriamine pentaacetic acid (p-SCN-Bn-DTPA) was used in this video at a concentration of 73 mM.

- Adjust the pH of the solution of ligand to between 5.5 and 7.0 by adding 1 M NH4OH. In this video, 0.2 mL of the 1 M NH4OH solution was used.

- Dissolve 1-2 equivalents of LnCl3 in water to produce a solution with a concentration of 5-1000 mM. In this video, EuCl3 and GdCl3 were used in concentrations of 111 mM. An excess of metal is often used to drive the metalation to completion and consequently simplify purification.

- Add the solution of LnCl3 to the solution of ligand while stirring.

- After the addition of LnCl3, adjust the pH of the resulting reaction mixture to between 5.5 and 7.0 by adding 0.2 M NH4OH. A total of 0.5 mL of the 0.2 M NH4OH solution was used in this video. If your ligand contains acid-sensitive functional groups, adjust the pH multiple times during this step. CAUTION - If the solution becomes too basic, any base sensitive functional groups, like isothiocyanate, will be rendered unusable for conjugation.

- Monitor the reaction via pH measurements. The reaction is complete when the pH remains constant.

2. Raising pH workup (not included in this video, but good for ligands without base-sensitive functional groups)

- Add concentrated NH4OH to the reaction mixture to adjust the pH to ≥11. This step will precipitate any uncomplexed metal as the insoluble hydroxide.

- Filter the supernatant through a 0.2 μm filter. If the reaction mixture clogs the filter, centrifuging and decanting prior to filtering is recommended.

- If dialysis will not be performed, remove solvent under reduced pressure (rotary evaporation or freeze drying is recommended).

- Steps 2.1-2.3 can be repeated if free lanthanide remains.

3. Dialysis workup

- Cut the dialysis tubing to an appropriate length (follow the manufacturer’s guidelines) to hold the sample volume while leaving extra length (approximately 10% of the sample volume). In this video, a 100-500 dalton molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) membrane was used, but larger MWCO tubing can be used as appropriate if conjugation is performed prior to metalation. Also, dialysis cassettes can be used as an alternative to dialysis tubing if desired.

- If appropriate based on the manufacturer’s guidelines, soak the cut dialysis tubing in water for 15 min at ambient temperature.

- Fill a dialysis reservoir (a 1 L beaker was used in this video) with water (dialysate). The dialysate volume should be approximately 100x that of the sample.

- Fold one end of the tubing twice and secure the folded portion of the tubing with a dialysis closure clamp. Wrap the end of the closure with a rubber band to ensure that it remains closed during dialysis.

- Filter the reaction mixture through a 0.2 μm filter, and load the filtrate into the open end of the tubing being careful not to tear the tubing. Be sure to leave enough head space to close the tubing.

- Fold the remaining open end of the tubing twice, secure with a closure, and wrap the closure with a rubber band as in step 3.4.

- Attach a glass vial containing air to the clamp on one end of the dialysis tubing using a rubber band. Attach a vial containing sand to the other clamp. These vials ensure that the tubing stays immersed in the dialysate.

- Place the full tubing in the dialysis reservoir that contains dialysate.

- Stir the dialysate using a magnetic stir plate at a slow speed (no vortexing) at ambient temperature.

- Change the dialysate 3x over the course of a day (in this video, the dialysate was changed at 2.5, 6.5, and 11.5 h), and then allow dialysis to continue overnight (for a total of 20-28 h of dialysis).

- Remove the dialysis tubing from the dialysate and carefully open one closure to remove the sample. Wash the dialysis tubing 3x with water and combine the washings with the sample.

- Remove the water under reduced pressure. Freeze drying is used in this video.

4. Assessment of the presence of free metal

- Dissolve the metal complex in acetate buffer (buffer preparation: Dissolve 1.4 mL of acetic acid in 400 mL water, adjust the pH to 5.8 with 1 M NH4OH, and add water to produce a total volume of 500 mL) and add the xylenol orange indicator (16 μM in pH 5.8 buffer). In this video, 0.3 mg of complex was dissolved in 0.3 mL of buffer and 3 mL of indicator solution was added.

- Detect the presence of free metal via observation of a color change of the indicator from yellow to violet.

- If desired, the amount of free metal can be quantified by creating a calibration curve1. Alternatively, the dye arsenazo III can be used instead of xylenol orange2. If free metal remains, the sample should be further purified using dialysis, a desalting column, or high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) prior to characterization.

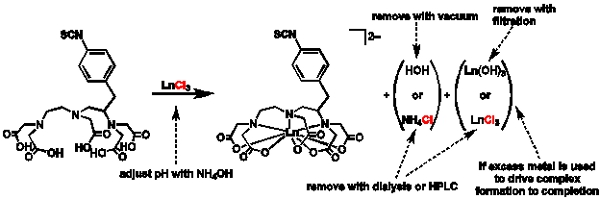

5. Determination of water-coordination number (q)

- Prepare a solution of the EuIII-containing complex (~1 mM) in H2O and another solution of the same concentration in D2O. Prior to analysis, the D2O solution must be evaporated and dissolved in D2O three times to remove residual H2O.

- Add the water solution to a clean cuvette, and place the cuvette into a spectrofluorometer.

- Perform excitation and emission scans to determine the maxima for each (~395 nm and ~595 nm, respectively).

- Perform a phosphorescence time-decay experiment using the following parameters: excitation and emission wavelengths determined from step 5.3, excitation and emission slit widths (5 nm), flash count (100), initial delay (0.01 ms), maximum delay (13 ms), and delay increment (0.1 ms). These conditions are appropriate for most complexes, but the maximum delay and increment values can be increased or decreased for species with extremely long or extremely short decay times.

- Repeat step 5.4 with the D2O solution prepared in step 5.1.

- From the luminescence-decay data obtained in 5.4 and 5.5, plot the natural log of intensity versus time. The slope of these lines are the decay rates (τ-1) (Figure 2). In this video, Microsoft Excel 2007 was used to generate the natural log plots from the raw data. Use the decay rates in the equation developed by Horrocks and coworkers (eq 1)3. If your ligand contains OH or NH groups coordinated to the metal, then the equation must be modified before use3.

eq 1:

6. Relaxivity measurements

- Select the desired application mode on the relaxation time analyzer: T1 (longitudinal relaxation time) or T2 (transverse relaxation time).

- Prepare a series of samples that contain different concentrations of GdIII-containing complex in an aqueous solvent. In this video, water was used as the solvent and solutions of 10.0, 5.00, 2.50, 1.25, 0.625, and 0 mM were prepared. Other aqueous solvents or buffers could be used, but it is important to use the solvent as the blank. The final volume of the sample is specific to the instrument that is being used.

- Place a sample in the instrument and let it sit for 5 min to equilibrate to the temperature of the instrument (37 °C in this video).

- Determine the relaxation time (in units of s) by adjusting the parameters of the software to obtain a smooth exponential curve for T1 or T2 (representative curves for T1 and T2 are shown in Figure 3).

- Repeat steps 6.3 and 6.4 for all samples including the blank.

- Calculate the inverse of the measured T1 or T2 values in units of s-1.

- Plot the T1-1 or T2-1 values versus GdIII concentration (in units of mM). Because of the hygroscopic nature of GdIII-containing complexes, confirm the concentration of GdIII using atomic absorption spectrophotometry or inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry. Fit the plot with a straight line. A representative plot is shown in Figure 4.

- The slope of the fitted line is the relaxivity (r1 or r2 for T1 and T2, respectively) and has units of mM-1s-1.

7. Representative Results

Representative data for the steps in this protocol have been included in the Tables and Figures section. In addition to the water-coordination number and relaxivity characterization described in the protocol, it is important to characterize final products using standard chemical techniques. The identity of the compound can be obtained using mass spectrometry, and representative mass spectra showing the diagnostic isotope patterns for GdIII- and EuIII-containing complexes are shown in Figure 5. Furthermore, for non-GdIIIlanthanide-containing complexes, NMR spectroscopy can be used for identification of the product. To characterize the purity of the complex, HPLC or elemental analysis or both can be used.

Figure 1. General scheme for metalation and purification: Scheme depicting the general procedure for metalation and reasons for choosing different purification routes.

Figure 2. Luminescence-intensity plot: Representative plot of the natural log of intensity versus time from section 5. The slopes of the lines generated from similar curves acquired for water and D2O solutions are used with eq 1 to characterize the water-coordination number of EuIII-containing complexes.

Figure 3. Relaxation decay time curves: Representative data for (left) T1 and (right) T2 acquisition. Deviations from these curve shapes would produce unreliable data.

Figure 4. Relaxivity determination: A representative plot of 1/T1 versus the concentration of GdIII. The slope of the fitted line is relaxivity and has units of mM-1s-1.

Figure 5. Mass spectra: Representative mass spectra showing the diagnostic isotope patterns for (left) GdIII-containing complexes and (right) EuIII-containing complexes. The black Gaussian peaks represent the theoretical isotope distribution and the red lines are the actual data.

Discussion

Given the increasing number of publications that include lanthanide-based contrast agents4-14, it is important that care is taken in preparing, purifying, and characterizing products to ensure reproducible and comparable results. These complexes are often considered challenging to purify and characterize relative to organic molecules due to their paramagnetic nature and the sensitivity of any functional groups that could be used for bioconjugation. We have described common methods for the synthesis, purificat...

Disclosures

No conflicts of interest declared.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge startup funds from Wayne State University (MJA), a grant from the American Foundation for Aging Research (SMV), and a Pathway to Independence Career Transition Award (R00EB007129) from the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health (MJA).

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Reagents and Equipment | Company | Catalogue number | |

|---|---|---|---|

| EuCl3•6H2O | Sigma-Aldrich | 203254-5G | |

| p-SCN-Bn-DTPA | Macrocyclics | B-305 | |

| ammonium hydroxide | EMD | AX1303-3 | |

| Spectra/Por Biotech Cellulose Ester (CE) Dialysis Membrane - 500 D MWCO | Fisher Scientific | 68-671-24 | |

| Millipore IC Millex-LG Filter Units | Fisher Scientific | SLLG C13 NL | |

| xylenol orange tetrasodium salt | Alfa Aesar | 41379 | |

| acetic acid | Fluka | 49199 | |

| D2O | Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. | DLM-4-25 | |

| water purifier | ELGA | Purelab Ultra | |

| high performance liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry | Shimadzu | LCMS-2010EV | |

| relaxation time analyzer | Bruker | mq60 minispec | |

| UV-vis spectrophotometer | Fisher Scientific | 20-624-00092 | |

| freeze dryer | Fisher Scientific | 10-030-133 | |

| pH meter | Hanna Instruments | HI 221 | |

| spectrofluorometer | HORIBA Jobin Yvon | Fluoromax-4 | |

| Molecular Weight Calculator version 6.46 by Matthew Monroe, downloaded October 17, 2009 | http://ncrr.pnl.gov/software/ | Molecular Weight Calculator |

References

- Barge, A., Cravotto, G., Gianolio, E., Fedeli, F. How to determine free Gd and free ligand in solution of Gd chelates. A technical note. Contrast Med. Mol. Imaging. 1, 184-188 (2006).

- Nagaraja, T. N., Croxen, R. L., Panda, S., Knight, R. A., Keenan, K. A., Brown, S. L., Fenstermacher, J. D., Ewing, J. R. Application of arsenazo III in the preparation and characterization of an albumin-linked, gadolinium-based macromolecular magnetic resonance contrast agent. J. Neurosci. Methods. 157, 238-245 (2006).

- Supkowski, R. M., Horrocks, W. D. On the determination of the number of water molecules, q, coordinated to europium(III) ions in solution from luminescence decay lifetimes. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 340, 44-48 (2002).

- Menjoge, A. R., Kannan, R. M., Tomalia, D. A. Dendrimer-based drug and imaging conjugates: design considerations for nanomedical applications. Drug Discovery Today. 15, 171-185 (2010).

- Que, E. L., Chang, C. J. Responsive magnetic resonance imaging contrast agents as chemical sensors for metals in biology and medicine. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 51-60 (2010).

- Uppal, R., Caravan, P. Targeted probes for cardiovascular MR imaging. Future Med. Chem. 2, 451-470 (2010).

- Major, J. L., Meade, T. J. Bioresponsive, cell-penetrating, and multimeric MR contrast agents. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 893-903 (2009).

- Datta, A., Raymond, K. N. Gd-hydroxypyridinone (HOPO)-based high-relaxivity magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) contrast agents. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 938-947 (2009).

- León-Rodríguez, L. M. D., Lubag, A. J. M., Malloy, C. R., Martinez, G. V., Gillies, R. J., Sherry, A. D. Responsive MRI agents for sensing metabolism in vivo. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 948-957 (2009).

- Castelli, D. D., Gianolio, E., Crich, S. G., Terreno, E., Aime, S. Metal containing nanosized systems for MR-molecular imaging applications. Coord. Chem. Rev. 252, 2424-2443 (2008).

- Caravan, P., Ellison, J. J., McMurry, T. J., Lauffer, R. B. Gadolinium(III) chelates as MRI contrast agents: structure, dynamics, and applications. Chem. Rev. 99, 2293-2352 (1999).

- Lauffer, R. B. Paramagnetic metal complexes as water proton relaxation agents for NMR imaging: theory and design. Chem. Rev. 87, 901-927 (1987).

- Yoo, B., Pagel, An overview of responsive MRI contrast agents for molecular imaging. Front. Biosci. 13, 1733-1752 (2008).

- Pandya, S., Yu, J., Parker, D. Engineering emissive europium and terbium complexes for molecular imaging and sensing. Dalton Trans. 23, 2757-2766 (2006).

- Nwe, K., Xu, H., Regino, C. A. S., Bernardo, M., Ileva, L., Riffle, L., Wong, K. J., Brechbiel, M. W. A new approach in the preparation of dendrimer-based bifunctional diethylenetriaminepentaacetic acid MR contrast agent derivatives. Bioconjugate Chem. 20, 1412-1418 (2009).

- Nwe, K., Bernardo, M., Regino, C. A. S., Williams, M., Brechbiel, M. W. Comparison of MRI properties between derivatized DTPA and DOTA gadolinium-dendrimer conjugates. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 18, 5925-5931 (2010).

- Caravan, P., Das, B., Deng, Q., Dumas, S., Jacques, V., Koerner, S. K., Kolodziej, A., Looby, R. J., Sun, W. -. C., Zhang, Z. A lysine walk to high relaxivity collagen-targeted MRI contrast agents. Chem. Commun. , 430-432 (2009).

- León-Rodríguez, L. M. D., Kovacs, Z. The synthesis and chelation chemistry of DOTA-peptide conjugates. Bioconjugate Chem. 19, 391-402 (2008).

- Boswell, C. A., Eck, P. K., Regino, C. A. S., Bernardo, M., Wong, K. J., Milenic, D. E., Choyke, P. L., Brechbiel, M. W. Synthesis, characterization, and biological evaluation of integrin αVβ3-targeted PAMAM dendrimers. Mol. Pharm. 5, 527-539 (2008).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionExplore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved