Experimentation using a Confederate

Overview

Source: Laboratories of Gary Lewandowski, Dave Strohmetz, and Natalie Ciarocco—Monmouth University

When orchestrating an experiment, it is important that the experience elicits the most natural reactions from the participants as possible. Researchers accomplish much of this through their creation of the experimental settings.

Many research projects focus on interactions between two or more people. In these situations the environment or setting must often be less natural; often only one person can be a true participant and others in the study need to be “confederates,” that is, allegedly unbiased participants whom, in actuality, act according to the researcher’s directions.

This video uses a two-group experiment to see if participants are more likely to imitate a person with more power versus similar power compared to the participant. The video also highlights the use of research confederates.

Psychological studies often use higher sample sizes than studies in other sciences. A large number of participants helps to better ensure that the population under study is better represented, i.e. the margin of error accompanied by studying human behavior is sufficiently accounted for. Further, human participants for research like this are often readily available and the experiment is quick and inexpensive to replicate so we want to use as many participants as possible. In this video we demonstrate this experiment using just one participant. However, as represented in the results, we used a total of 156 participants to reach the experiment’s conclusions.

Procedure

1. Define key variables.

- Create an operational definition (i.e., a clear description of exactly what a researcher means by a concept) of power.

- For the purposes of this experiment, power is measured by relative authority on the college campus, e.g., a residence hall assistant has more power than a student that does not hold this position.

- Create an operational definition (i.e., a clear description of exactly what a researcher means by a concept) of imitation.

- For purposes of this experiment, imitation is defined as the participant’s non-conscious mimicking of the confederate by making similar movements with their feet and hands.

2. Conduct the study.

- Meet the student/participant at the lab.

- Provide participant with informed consent, a brief description of the research, a sense of the procedure, an indication of potential risks/benefits, the right of withdrawal at any time, and a manner to get help if they experience discomfort.

- Have the participant sit at a desk on the window side of a one-way mirror.

- Tell the participant that you would like them to remember the behaviors of another participant (a confederate in actuality) who will sit on the mirror side of the one-way mirror while they work on GRE Math problems (Figure 1).1

Figure 1: An example of the GRE math problems given to the confederate. - Train the confederate.

- Confederates, also known as stooges, are part of the experiment and act exactly as the researcher instructs. Participants are led to believe that a confederate is a participant.

- Train the confederate to engage in 7 key behaviors: playing with their hair, putting a pen in their mouth, tapping their fingers, touching their face, wrinkling their nose, making whistling sounds, and leaning back in their chair.

- For consistency, the confederate should match each behavior to a specific question on the GRE math problems. For example, when the confederate works on problem 1, they should play with hair, when they work on question 2, they should put a pen in their mouth, for question 3, they should tap their fingers, etc. This will ensure that all behaviors occur at the same relative time for all participants.

- Lead the confederate to their chair in front of the mirror-side of the one-way mirror.

- Treat the confederate like a participant, giving them informed consent (as described in 2.2 above), and then explain that the participant will complete the sheet of GRE math problems.

- On the window side of the one-way mirror, the participant has clear sight and sound of this interaction between the researcher and the confederate.

- Return to the participant with a pen and a copy of the GRE problems. Instruct the participant to mark ones they think the confederate got correct with a star, and those they think the confederate got incorrect with an X.

- In one condition, tell the participant that the confederate is a head residence hall assistant on campus.

- In the other condition tell the participant that the confederate is another participant “just like you.”

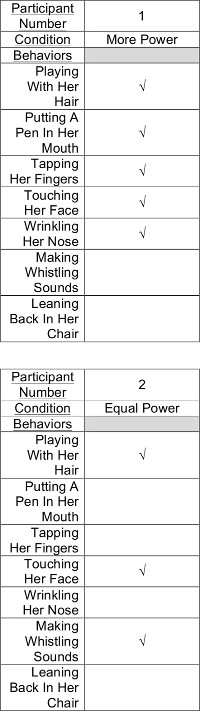

- Sit off to the side of the participant and record the participant’s behaviors on a chart (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Chart used by experimenter to record participant’s behavior.

3. Debrief the participant.

- Tell the participant the nature of the study.

- “Thank you for participating. In this study I was trying to determine if a fellow participant’s perceived power or authority would increase the chances that a participant like you would mimic their behavior. There were two groups in the study, one group was told the person they were observing is a residence hall assistant, while the other group was told they were just another participant. We hypothesized that those who observed the resident hall assistant would be more likely to mimic their behavior because they are an authority figure.”

- Explain explicitly why deception was necessary for the experiment.

- “We want to tell you about the deception we used in this study. We used deception by telling you the person you observed was another participant, but in reality they were a part of the study and served as a confederate. We did this to make the experiment feel real and to ensure that person being observed acting similarly for each participant in the study. If participants were to know the true reasoning and hypothesis behind the study, they may perform in an unnatural way by trying to live up to the experimenter’s perceived expectations. To eliminate this problem, it was necessary for us to use the confederate. Because of the nature of the deception, it is quite natural for participants to not realize that they were being deceived.”

Results

The procedure demonstrated in this research was repeated 155 times so that the results reflect data from 156 total participants. 78 of the participants were told that the confederate was a head residence hall assistant (first condition) while the other 78 participants were told that the confederate has no such position of power, i.e., was just a regular student like the participant (second condition).

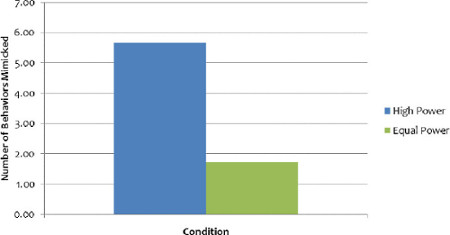

The data graphed reflect the average number of behaviors the participant mimicked while observing the confederate (Figure 3). Recall that there were 7 possible behaviors to mimic so participants’ scores could range between 0 and 7.

To determine if there were differences between the high and equal power conditions, a t-test was performed for independent means. The results indicated that participants who believed the confederate had higher power mimicked a greater number of behaviors than those who believed they had similar power.

Figure 3: Average number of behaviors mimicked by perceived power condition.

Application and Summary

Confederates are common in psychology research. For example, a confederate can give participants specific suggestions or information that can later influence memory.2 Researchers also use confederates in field studies to recreate everyday interactions. For example, when a male confederate interacted with a baby, women liked him better than when he ignored the baby.3 This study replicates and extends previous research on embodiment, which showed that those who want to feel affiliated to another person are more likely to engage in nonconscious mimicry.4 A number of factors may influence the extent to which a person non-consciously mimics another. For example, a recent experiment induced participants to feel a sense of prideful, positive, or neutral feelings.5 The results indicated that participants who felt a sense of pride were less likely to mimic a confederate’s foot shaking behavior.

References

- Seltzer, N., & The Staff of the Princeton Review. 1,014 GRE practice questions. (L. Braswell, R. Lessem, S. Coppock, & H. Brady, Eds.). New York, NY: Random House (2009).

- Davis, S. D., & Meade, M. L. Both young and older adults discount suggestions from older adults on a social memory test. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review. 20 (4), 760-765. doi:10.3758/s13423-013-0392-5 (2013).

- Guéguen, N. Cues of men's parental investment and attractiveness for women: A field experiment. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 24 (3), 296-300. doi:10.1080/10911359.2013.820160 (2014).

- Lakin, J. L., & Chartrand, T. L. Using nonconscious behavioral mimicry to create affiliation and rapport. Psychological Science. 14 (4), 334-339 doi:10.1111/1467-9280.14481 (2003).

- Dickens, L., & DeSteno, D. Pride attenuates nonconscious mimicry. Emotion. 14 (1), 7-11. doi:10.1037/a0035291 (2014).

Skip to...

Videos from this collection:

Now Playing

Experimentation using a Confederate

Experimental Psychology

17.8K Views

From Theory to Design: The Role of Creativity in Designing Experiments

Experimental Psychology

18.4K Views

Ethics in Psychology Research

Experimental Psychology

29.1K Views

Realism in Experimentation

Experimental Psychology

8.3K Views

Perspectives on Experimental Psychology

Experimental Psychology

5.6K Views

Pilot Testing

Experimental Psychology

10.3K Views

Observational Research

Experimental Psychology

13.0K Views

The Simple Experiment: Two-group Design

Experimental Psychology

74.0K Views

The Multi-group Experiment

Experimental Psychology

22.8K Views

Within-subjects Repeated-measures Design

Experimental Psychology

23.0K Views

The Factorial Experiment

Experimental Psychology

73.2K Views

Self-report vs. Behavioral Measures of Recycling

Experimental Psychology

11.8K Views

Reliability in Psychology Experiments

Experimental Psychology

8.5K Views

Placebos in Research

Experimental Psychology

11.6K Views

Manipulating an Independent Variable through Embodiment

Experimental Psychology

8.5K Views

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved