A subscription to JoVE is required to view this content. Sign in or start your free trial.

Method Article

استئصال ساق العين لزيادة نضج المبيض في سرطان الطين

In This Article

Erratum Notice

Summary

تم إجراء بروتوكولين لاستئصال ساق العين (أي نهج الكي والجراحة) على إناث السرطانات المخدرة. أدى استئصال ساق العين لسرطان البحر الطيني إلى تسريع نضج المبايض دون تقليل معدل البقاء على قيد الحياة.

Abstract

سرطان البحر الطيني (Scylla spp.) هي أنواع قشريات مهمة تجاريا يمكن العثور عليها في جميع أنحاء منطقة المحيط الهندي وغرب المحيط الهادئ. أثناء الاستزراع ، يعد تحريض نضوج المبيض مهما لتلبية طلب المستهلكين على سرطان البحر الطيني الناضج وتسريع إنتاج البذور. الاجتثاث Eyetalk هو أداة فعالة لتعزيز نضوج المبيض في سرطان الطين. ومع ذلك ، لا يوجد بروتوكول قياسي لاستئصال ساق العين من سرطان الطين. في هذه الدراسة ، تم وصف تقنيتين لاستئصال ساق العين: الكي (استخدام المعدن الساخن لاستئصال ساق العين لسرطان البحر المخدر) والجراحة (إزالة ساق العين باستخدام مقص جراحي). قبل استئصال ساق العين ، تم تخدير الإناث الناضجة جنسيا (CW > 86 ملم) باستخدام كيس ثلج (-20 درجة مئوية) بمياه البحر. عندما وصلت درجة حرارة الماء إلى 4 درجات مئوية ، تمت إزالة كيس الثلج من الماء. تم استخدام مياه البحر المتدفقة (درجة الحرارة المحيطة: 28 درجة مئوية) للتعافي من التخدير مباشرة بعد استئصال ساق العين. لم تحدث الوفيات أثناء أو بعد عملية استئصال العين. أدى بروتوكول استئصال ساق العين المقدم هنا إلى تسريع نضوج المبيض لسرطان الطين.

Introduction

جميع أنواع سرطان الطين الأربعة التي تنتمي إلى جنس Scylla هي أنواع قشريات مهمة تجاريا في تربية الأحياء المائية1،2. يحدث نمو القشريات ، بما في ذلك سرطان البحر الطيني ، وتحولها من مرحلة ما قبل النضج (دون البالغين أو سن البلوغ) إلى مرحلة النضج الجنسي (البالغين) من خلال عملية طرح الريش التي تنطوي على التساقط الدوري للهياكل الخارجية الأكبر سنا والأصغر. يستخدم عرض الدرع (CW) ، و chelipeds ، ومورفولوجيا رفرف البطن على نطاق واسع لتحديد النضج الجنسي ل Scylla spp. 3,4,5. يتم تنظيم عملية طرح الريش من خلال عمل الهرمونات المختلفة وتتطلب كمية هائلة من الطاقة6. بالإضافة إلى عملية الريش الطبيعية ، فإن فقدان الأطراف ، إما طواعية أو بسبب عوامل خارجية ، يسرع من طرح سرطان البحر دون التأثير على معدل بقائهعلى قيد الحياة 7،8،9. لذلك ، يستخدم بضع الأطراف الذاتي بشكل شائع لتحريض الذوبان في صناعة زراعة سرطان البحر الطيني ذو القشرة الناعمة 7,9.

الاجتثاث أحادي الجانب أو ثنائي العين شائع في الغالب في جمبري المياه العذبة والجمبري البحري لنضوج الغدد التناسلية وإنتاج البذور10،11،12،13. تشمل تقنيات استئصال ساق العين الشائعة في القشريات ما يلي: (ط) الربط عند قاعدة ساق العين باستخدام سلسلة14,15 ؛ (ii) كي ساق العين باستخدام ملقط ساخن أو أجهزة الكي الكهربائي16 ؛ (iii) إزالة أو قرص مباشر من ساق العين لترك جرح مفتوح12 ؛ و (د) إزالة محتويات ساق العين من خلال شق بعد تقطيع الجزء البعيد من العين بشفرةحلاقة 17. تعد الأعضاء X ذات ساق العين من أعضاء الغدد الصماء المهمة في القشريات لأنها تنظم هرمونات ارتفاع السكر في الدم في القشريات (CHH) ، والهرمونات المثبطة للذوبان (MIH) ، والهرمونات المثبطة لتكوين الجسم (VIH) 6،18،19،20،21،22. تقوم أجهزة Eyetalk X (أو مجمع الغدة الجيبية) بتجميع وإطلاق هرمونات تثبيط الغدد التناسلية (GIH) ، والمعروفة أيضا باسم هرمونات تثبيط تكوين الجسم (VIH) ، والتي تنتمي إلى عائلة هرمون الببتيد العصبي6. يقلل الاستئصال أحادي الجانب أو الثنائي من تخليق GIH ، مما يؤدي إلى هيمنة الهرمونات المحفزة (أي هرمونات تحفيز الغدد التناسلية ، GSH) وتسريع عملية نضج المبيض في القشريات23،24،25،26. بدون تأثير GIH بعد استئصال ساق العين ، تكرس إناث القشريات طاقتها لتطوير المبيض27. وقد وجد أن استئصال ساق العين من جانب واحد يكفي لتحريض نضوج المبيض في القشريات11 وأن ساق العين المستأصل للروبيان وسرطان البحر يمكن أن يتجدد بعد عدة عمليات ذوبان28. هناك أربع مراحل تطور المبيض مسجلة في Scylla spp.: i) غير ناضجة (المرحلة 1) ، ii) النضج المبكر (المرحلة 2) ، iii) مرحلة ما قبل النضج (المرحلة 3) ، و iv) ناضجة تماما (المرحلة 4) 29،30. تم العثور على مرحلة المبيض غير الناضجة في الإناث غير الناضجة. بعد سن البلوغ والتزاوج ، يبدأ المبيض غير الناضج في التطور وينضج أخيرا (المرحلة 4) قبل التفريخ31.

يعد بروتوكول استئصال ساق العين ضروريا لتطوير أمهات سرطان البحر الطيني وإنتاج البذور. في سوق الأغذية العالمية ، يفضل المستهلكون سرطان البحر الطيني الناضج مع المبايض الناضجة تماما (المرحلة 4) بدلا من السرطانات ذات المحتوى العضلي العالي ، وبالتالي ، يكون لها قيمة تجارية أعلى ، حتى أعلى من الذكور الكبيرة. لا يوجد بروتوكول كامل لاستئصال ساق العين لسرطان الطين. يقلل بروتوكول استئصال ساق العين في هذا العمل من الإجهاد باستخدام سرطان البحر المخدر بالكامل ويقلل من الإصابة الجسدية للأفراد من لدغات السلطعون. هذا البروتوكول سهل وفعال من حيث التكلفة. هنا ، نقدم بروتوكولا لاستئصال ساق العين ل Scylla spp. التي يمكن أن تحفز نضوج الغدد التناسلية. تم اختبار تقنيتين لاستئصال ساق العين (الكي والجراحة) ومقارنة كفاءتهما بناء على معدل نمو الغدد التناسلية لسرطان البحر الطيني الإناث.

Protocol

يتبع هذا البروتوكول مدونة الممارسات الماليزية لرعاية واستخدام الحيوانات للأغراض العلمية التي حددتها جمعية علوم المختبر في ماليزيا. تم التضحية بالعينات التجريبية وفقا لدليل المعاهد الوطنية للصحة لرعاية واستخدام المختبر (منشورات المعاهد الوطنية للصحة رقم 8023 ، المنقحة عام 1978). تم جمع سرطان البحر الطيني الناضج جنسيا (سلطعون الطين البرتقالي S. olivacea) من السوق المحلية (5 ° 66′62′ شمالا ، 102 ° 72′33′ شرقا) في Setiu Wetlands في ماليزيا. تم تحديد أنواع سرطان الطين بناء على الخصائص المورفولوجية1.

1. جمع العينات وتطهيرها

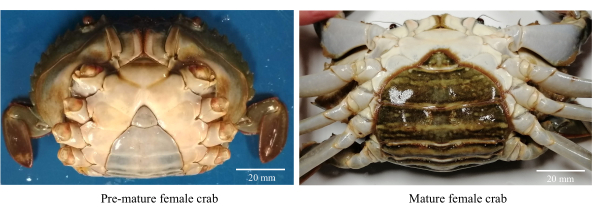

- اجمع سرطانات الطين الأنثوية الصحية والنشطة والمبكرة (الشكل 1).

ملاحظة: السرطانات الإناث قبل النضج لها سديلات بطن مثلثة وفاتحة اللون مع نطاق CW يبلغ 80-85 ملم. - اغسل السرطانات بماء الصنبور المكلور (المياه العذبة) لإزالة الحطام والطفيليات الأسموفيلية.

- نقع السرطانات في 150 جزء في المليون من الفورمالديهايد مع ملوحة 20 جزء في المليون لمدة 30 دقيقة.

- حافظ على التهوية المستمرة واللطيفة باستخدام الأحجار الهوائية أثناء معالجة الفورمالديهايد. يمكن أن يكون مصدر التهوية إما من خط تهوية مركزي أو مضخة تهوية حوض السمك.

- اغسل السرطانات بمياه البحر المتدفقة لإزالة أي بقايا من الفورمالديهايد.

الشكل 1: مورفولوجيا البطن لإناث سرطان البحر الطيني المستخدمة لتحديد مراحل النضج الجنسي. يرجى النقر هنا لعرض نسخة أكبر من هذا الرقم.

2. التأقلم

- انقل كل أنثى مطهرة إلى خزان دائري منفصل سعة 32 لترا.

- تربية الإناث لمدة 3 أيام في ملوحة 20 جزء في المليون والاستمرار في التغذية مرتين يوميا (صباحا 09:00 صباحا ومساء 20:00 مساء) مع الأسماك البحرية المفرومة بحوالي 4٪ -5٪ من وزن جسم السلطعون.

- قم بإزالة الأعلاف الزائدة وغير المأكولة عن طريق السحب قبل الرضاعة الصباحية.

- تبادل 10٪ من مياه البحر التي تربى السلطعون (20 جزء في الألف) يوميا.

3. الريش المستحث للنضج الجنسي

- قطع جميع الأرجل باستثناء أرجل السباحة باستخدام مقص معقم.

- قبض على السلطعون بشبكة مغرفة ، وأمسك السلطعون بعناية. قطع كل من chelipeds أولا ثم الساقين المشي في المفصل الثاني باستخدام مقص. سيقوم السلطعون بتقسيم الزوائد التالفة تلقائيا. التخدير غير مطلوب لبضع الجسم للأطراف.

- اغسل السلطعون في المياه العذبة مباشرة بعد بضع الأطراف الذاتي.

- انقل السرطانات ذاتية الأطراف بشكل فردي إلى سلال بلاستيكية مثقبة (28 سم طول × 22 سم عرض × 7 سم ارتفاع) ، وضعها في خزان من الألياف الزجاجية (305 سم طول × 120 سم عرض × 60 سم ارتفاع).

ملاحظة: يمكن ربط سلتين وقصهما معا. يتم استخدام السلة العلوية كغطاء حتى لا يتمكن السلطعون من الهروب من السلة. - استخدم نظام الاستزراع المائي المعاد تدويره (RAS) بملوحة 20 جزء في المليون وعمق مياه لا يقل عن 10 سم لضمان غمر السلة البلاستيكية بأكملها.

- استمر في إطعام أنثى السلطعون ذاتية الأطراف بالأسماك البحرية المفرومة مرتين يوميا بنسبة 5٪ -7٪ من وزن جسم السلطعون.

- قم بتربية السرطانات حتى تنضج جنسيا من خلال طرح الريش (35 يوما).

ملاحظة: يمكن تخطي الريش المستحث لنضوج المبيض التجاري وإنتاج البذور مع سرطان البحر الطيني البري الناضج. يجب أن تتأقلم الإناث الناضجة المحصودة من البرية وتخضع مباشرة للتخدير بالصدمة الباردة والاجتثاث اللاحق للعين.

4. التخدير

- حدد الإناث الناضجة جنسيا مع رفرف بطن بيضاوي داكن اللون مع CW >86 مم (الشكل 1).

- قبض على سرطان البحر مع شبكة مغرفة ، والاحتفاظ بها بشكل فردي في أحواض السمك الصغيرة للتخدير.

- بعد 5 دقائق من فترة التأقلم ، أضف 2-فينوكسي إيثانول (2-PE) بمعدل 2 مل / لتر في كل حوض مائي واترك 15 دقيقة من العلاج بالتخدير.

- تأكد من تخدير السرطانات بالكامل بسبب قلة الحركة التلقائية.

5. الاجتثاث العيني

- تقنية الكي

- نفذ جميع الإجراءات أعلى الطاولة وفي منطقة مفتوحة.

- خذ قضيبا معدنيا مسطحا من النيكل والصلب (على سبيل المثال ، مفك البراغي) بمقبض خشبي أو بلاستيكي ، وقم بتغطية المقبض بمنشفة قطنية مبللة.

- تعقيم اثنين من ملقط الجراحية غير القابل للصدأ في الأوتوكلاف.

- قم بإعداد 70٪ من الإيثانول في زجاجة رذاذ واحفظه بعيدا عن أي مصادر متعلقة بالحريق ، مثل شعلة النفخ ومفك البراغي الأحمر الساخن. جهز المناديل الورقية للاستخدام.

ملاحظة: الإيثانول شديد الاشتعال. الحفاظ على مسافة آمنة من مصادر الحريق. - قم بتوصيل موقد اللحام بأسطوانة غاز (البوتان) بإحكام.

تنبيه: اتبع التعليمات الموجودة على موقد اللحام وأسطوانة الغاز. تأكد من إيقاف تشغيل موقد اللحام عند التوصيل بأسطوانة الغاز. اقرأ واتبع جميع احتياطات السلامة من الحرائق المذكورة على أسطوانة الغاز. - ارتداء قفازات قطنية سميكة لتجنب الإصابة من الأجسام الساخنة.

- ضع طرف القضيب المعدني لنار موقد اللحام حتى يصبح القضيب المعدني أحمر فاتح.

- غطي السلطعون المخدر بمنشفة قطنية مبللة.

ملاحظة: قم بتغطية هوائيات السلطعون لتجنب التلف غير الضروري. - امسك عين واحدة من السلطعون بالملقط المعقم.

ملاحظة: تعقيم الملقط في الأوتوكلاف للاستخدام لأول مرة ، وتطهيره باستخدام 70٪ من الإيثانول للاستخدام اللاحق على السرطانات الأخرى. - امسك الطرف المسطح المعدني الأحمر الساخن على عين السلطعون واضغط قليلا لمدة 10-15 ثانية حتى يتحول لون ساق العين إلى اللون البرتقالي أو البرتقالي المحمر. كن حذرا عند إجراء هذه الخطوة لتجنب تلف الهياكل المجاورة.

ملاحظة: هناك حاجة إلى شخصين لتنفيذ استئصال العين باتباع طريقة الكي: أحدهما لحمل السلطعون والآخر لإجراء عملية الاستئصال. - قم بتطهير الملقط برذاذ الإيثانول بنسبة 70٪ لضمان عدم انتقال التلوث بين السرطانات.

ملاحظة: قم بهذه الخطوة فقط على الأقل انتظر لمدة 5 دقائق بعد إجراء استئصال ساق العين لضمان تبريد الملقط قبل التطهير باستخدام 70٪ من الإيثانول لمنع مخاطر الحريق المحتملة. - بعد إجراء استئصال ساق العين على جميع السرطانات ، اغمس القضيب المعدني الفولاذي الساخن من النيكل (مفك البراغي) في ماء الصنبور.

- تطهير منشفة قبل إعادة استخدامها. يمكن استخدام مناشف متعددة لتوفير الوقت.

ملاحظة: اغسل المنشفة بماء الصنبور ، واغمسها في 30 جزء في المليون من الماء المعالج بالكلور لمدة 5 دقائق. ثم اغسل المنشفة بماء الصنبور مرة أخرى ، واغمسها في محلول ثيوسلفات الصوديوم 1 جم / لتر. - احتفظ بموقد اللحام في مكان آمن بعد إيقاف تشغيله ، وانتظر حتى يعود إلى درجة الحرارة البيئية (حوالي 30 دقيقة) قبل فصله.

- تقنية الجراحة

- نفذ الإجراء في منطقة جيدة التهوية.

- تعقيم اثنين من المقصات الجراحية والملقط في الأوتوكلاف.

- صب 50 mL من الإيثانول 70٪ في كأس زجاجية سعة 100 mL.

- ارتداء قفازات قطنية سميكة.

- امسك السلطعون المخدر وقم بتغطيته بمنشفة قطنية مبللة.

- امسك عين واحدة من السلطعون بالملقط المعقم.

- قطع ساق العين بسرعة باستخدام مقص جراحي معقم.

ملاحظة: قد يتم فقدان الدملمف من الجزء المصاب من السلطعون. - اغمس المقص والملقط في 70٪ من الإيثانول بعد كل استخدام ، وجففهم باستخدام المناديل الورقية قبل إعادة الاستخدام.

6. رعاية ما بعد التخدير

- قم بإعداد 20 جزء في المليون من مياه البحر المفلترة ، واحتفظ بها في خزان علوي مع تهوية مستمرة.

- قم بتوصيل أنبوب مرن بالخزان العلوي لتدفق مياه الجاذبية.

- مباشرة بعد استئصال ساق العين ، ضع السلطعون في السلة ، وعرض السلطعون لمياه البحر المتدفقة (درجة حرارة الماء المحيط: 28 درجة مئوية) من الخزان العلوي.

- حافظ على تدفق مياه البحر ، وراقب السلطعون حتى يتمكن من التحرك تلقائيا ، مما يشير إلى الشفاء من التخدير.

ملاحظة: يمكن تحضير مياه البحر في خزان أرضي ، ويمكن استخدام مضخة مياه غاطسة لتدفق المياه. - احتفظ بالسرطانات بشكل فردي في مياه البحر 20 جزء في الألف مع التهوية في حوض السمك لمدة 30 دقيقة لمزيد من المراقبة.

ملاحظة: سيتم استزراع السرطانات المستعادة بشكل فردي في عملية استزراع التفريخ اللاحقة.

7. مراقبة نضوج المبيض

- تربية الأمهات

- نقل السرطانات الناضجة إلى خزانات دائرية فردية سعة 32 لترا.

- استمر في التغذية بالأسماك البحرية المفرومة (المجمدة عند -20 درجة مئوية) مرتين يوميا (صباحا 09:00 صباحا ومساء 20:00 مساء) ، وقم بإزالة الأعلاف غير المأكولة قبل التغذية الصباحية.

- قم بتربية قطعان التفريخ بشكل فردي لمدة 30 يوما في ملوحة 20 جزء في المليون.

- إزالة البراز ، وتبادل 10 ٪ من مياه البحر (20 جزء في الألف) يوميا.

- تشريح

- نظف صينية التشريح والمقص والملقط بنسبة 70٪ من الإيثانول.

- تخدير الإناث بشكل فردي باستخدام طريقة التخدير بالغمر 2-PE.

- اختر عشوائيا الإناث الناضجة حديثا (بعد طرح الإناث قبل الأوان) التي لم تمر باستئصال ساق العين لتأكيد مراحل الغدد التناسلية.

- التضحية بجميع الإناث التجريبية التي تم استئصال ساق العين بشكل فردي ، وتحديد مراحل نضج الغدد التناسلية. تدمير العقد الصدرية من سرطان البحر باستخدام المخرز معقم حاد. قم بإزالة الدرع العلوي أولا ثم الكبد لجعل المبيض مرئيا. مراقبة لون المبيض ، وتحديد مرحلة نضج المبيض (الشكل 2).

- تحديد مراحل نضج المبيض

- مراقبة لون المبيض بالعين المجردة أو تحت المجهر المجسم.

- تحديد مراحل نضج المبيض على أساس التلوين30: غير ناضجة (المرحلة 1) يظهر لون أبيض شفاف أو دسم. يظهر النضج المبكر (المرحلة 2) لونا شاحبا إلى أصفر فاتح ؛ (iii) يظهر النضج المسبق (المرحلة 3) لونا أصفر إلى برتقالي فاتح ؛ و (iv) النضج الكامل (المرحلة 4) يظهر اللون البرتقالي الداكن إلى المحمر.

النتائج

نضوج الغدد التناسلية

تم العثور على أنسجة المبيض البيضاء الكريمية (المبايض غير الناضجة ، المرحلة 1) في 100 ٪ من الإناث تشريح (ن = 6) قبل إجراء الاجتثاث العينية (الشكل 2). كان معدل نضج الغدد التناسلية لإناث السرطانات المستئصة من ساق العين (ن = 63 ؛ 31 أنثى بتقنية الكي و 32 أنث...

Discussion

تم تطوير هذا البروتوكول لاستئصال ساق العين لسرطان البحر الطيني ، Scylla spp. ، ويمكن تطبيقه كطريقة فعالة للحث على نضوج الغدد التناسلية. يمكن تكرار هذا البروتوكول بسهولة لنضوج المبيض التجاري لسرطان البحر الطيني ويمكن تنفيذه لتقليل الفترة الكامنة (الوقت من تفريخ إلى آخر) في إنتاج بذور سرطا?...

Disclosures

ليس لدى أي من المؤلفين أي تضارب في المصالح.

Acknowledgements

تم دعم هذه الدراسة من قبل وزارة التربية والتعليم في ماليزيا ، في إطار برنامج مركز التميز للمؤسسات العليا (HICoE) ، ماليزيا ، المعتمد لدى معهد الاستزراع المائي ومصايد الأسماك الاستوائية ، جامعة ماليزيا تيرينجانو (Vot No. 63933 و Vot No. 56048). نحن نعترف بدعم جامعة ماليزيا تيرينجانو و Sayap Jaya Sdn. Bhd. من خلال منحة أبحاث الشراكة الخاصة (رقم التصويت 55377). كما تم الاعتراف بمنصب زميل أكاديمي مساعد من جامعة سينز ماليزيا إلى خور وايهو وحنفية فزان.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Aeration tube | Ming Yu Three | N/A | aquarium and pet shop |

| Airstone | Ming Yu Three | N/A | aquarium and pet shop |

| Autoclave machine | HIRAYAMA MANUFACTURING CORPORATION | N/A | MADE IN JAPAN |

| Bleaching powder (Hi-Chlon 70%) | Nippon Soda Co.Ltd,Japan | N/A | N/A |

| Blow torch | MR D.I.Y. Group Berhad | N/A | N/A |

| Circular tank (32L) | BEST PLASTIC INDUSTRY SDN. BHD. | N/A | N/A |

| Cotton hand gloves (thick) | MR D.I.Y. Group Berhad | N/A | N/A |

| Cotton towel | MR D.I.Y. Group Berhad | N/A | N/A |

| Digital thermometer | Hanna Instrument | HI9814 | Hanna Instruments GroLine Hydroponics Waterproof pH / EC / TDS / Temp. Portable Meter HI9814 |

| Digital Vernier Caliper | INSIZE Co., Ltd. | N/A | |

| Dissecting tray | Hatcheri AKUATROP | N/A | Research Center of Universiti Malaysia Terengganu |

| Dropper bottle/Plastic Pipettes Dropper | Shopee Malaysia | N/A | N/A |

| Ethanol 70% | Thermo Scientific Chemicals | 033361.M1 | Diluted to 70% using double distilled water |

| Fiberglass tank (1 ton) | Hatcheri AKUATROP | N/A | Research Center of Universiti Malaysia Terengganu |

| Fine sand | N/A | N/A | collected from Sea beach of Universiti Malaysia Terengganu |

| First Aid Kits | Watsons Malaysia | N/A | N/A |

| Flat head nickel steel metal rod (Screw driver) | MR D.I.Y. Group Berhad | N/A | N/A |

| Formaldehyde | Thermo Scientific Chemicals | 119690010 | |

| Gas cylinder (butane gas) for blow torch | MR D.I.Y. Group Berhad | N/A | N/A |

| Gas lighter gun (long head) | MR D.I.Y. Group Berhad | N/A | N/A |

| Glass beaker (100 mL)) | Corning Life Sciences | 1000-100 | |

| Ice bag | Watsons Malaysia | N/A | N/A |

| Perforated plastic baskets | Eco-Shop Marketing Sdn. Bhd. | N/A | N/A |

| PVC pipe 15mm | Bina Plastic Industries Sdn Bhd (HQ) | N/A | N/A |

| Refractometer | ATAGO CO.,LTD. | ||

| Refrigerator | Sharp Corporation Japan | N/A | Chest Freezer SHARP 110L - SJC 118 |

| Scoop net | MR D.I.Y. Group Berhad | N/A | |

| Seawater | Hatcheri AKUATROP | N/A | Research Center of Universiti Malaysia Terengganu |

| Siphoning pipe | MR D.I.Y. Group Berhad | N/A | N/A |

| Spray bottle | Mr. DIY Sdn Bhd | N/A | N/A |

| Stainless surgical forceps | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Stainless surgical scissors | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Submersible water pump | AS | N/A | model: Astro 4000 |

| Tincture of iodine solution (Povidone Iodine) | Farmasi Fajr Sdn Bhd | N/A | N/A |

| Tissue paper | N/A | N/A | |

| Transparent plastic aquarium | Ming Yu Three | N/A | aquarium and pet shop |

| Waterproof table | Hatcheri AKUATROP | N/A | Research Center of Universiti Malaysia Terengganu |

References

- Keenan, C. P., Davie, P. J. F., Mann, D. L. A revision of the genus Scylla de Haan, 1833 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Portunidae). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 46 (1), 217-245 (1998).

- Fazhan, H., et al. Morphological descriptions and morphometric discriminant function analysis reveal an additional four groups of Scylla spp. PeerJ. 8, e8066 (2020).

- Ikhwanuddin, M., Bachok, Z., Hilmi, M. G., Azmie, G., Zakaria, M. Z. Species diversity, carapace width-body weight relationship, size distribution and sex ratio of mud crab, genus Scylla from Setiu Wetlands of Terengganu coastal waters Malaysia. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management. 5 (2), 97-109 (2010).

- Ikhwanuddin, M., Bachok, Z., Mohd Faizal, W. W. Y., Azmie, G., Abol-Munafi, A. B. Size of maturity of mud crab Scylla olivacea (Herbst, 1796) from mangrove areas of Terengganu coastal waters. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management. 5 (2), 134-147 (2010).

- Waiho, K., et al. On types of sexual maturity in brachyurans, with special reference to size at the onset of sexual maturity. Journal of Shellfish Research. 36 (3), 807-839 (2017).

- Mykles, D. L., Chang, E. S. Hormonal control of the crustacean molting gland: Insights from transcriptomics and proteomics. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 294, 113493 (2020).

- Fujaya, Y., et al. Is limb autotomy really efficient compared to traditional rearing in soft-shell crab (Scylla olivacea) production. Aquaculture Reports. 18, 100432 (2020).

- Waiho, K., et al. Moult induction methods in soft-shell crab production. Aquaculture Research. 52 (9), 4026-4042 (2021).

- Rahman, M. R., et al. Evaluation of limb autotomy as a promising strategy to improve production performances of mud crab (Scylla olivacea) in the soft-shell farming system. Aquaculture Research. 51 (6), 2555-2572 (2020).

- Okumura, T., et al. Expression of vitellogenin and cortical rod proteins during induced ovarian development by eyestalk ablation in the kuruma prawn, Marsupenaeus japonicus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 143 (2), 246-253 (2006).

- Pervaiz, P. A., Jhon, S. M., Sikdar-bar, M. Studies on the effect of unilateral eyestalk ablation in maturation of gonads of a freshwater prawn Macrobrachium dayanum. World Journal of Zoology. 6 (2), 159-163 (2011).

- Primavera, J. H. Induced maturation and spawning in five-month-old Penaeus monodon Fabricius by eyestalk ablation. Aquaculture. 13 (4), 355-359 (1978).

- Shyne Anand, P. S., et al. Reproductive performance of wild brooders of Indian white shrimp, Penaeus indicus: Potential and challenges for selective breeding program. Journal of Coastal Research. 86 (sp1), 65 (2019).

- Diarte-Plata, G., et al. Eyestalk ablation procedures to minimize pain in the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium americanum. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 140 (3-4), 172-178 (2012).

- Vargas-Téllez, I., et al. Impact of unilateral eyestalk ablation on Callinectes arcuatus (Ordway, 1863) under laboratory conditions: Behavioral evaluation. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research. 49 (4), 576-594 (2021).

- Chu, K. H., Chow, W. K. Effects of unilateral versus bilateral eyestalk ablation on molting and growth of the shrimp, Penaeus chinensis Osbeck, 1765) (Decapoda, Penaeidea). Crustaceana. 62 (3), 225-233 (1992).

- Taylor, J. Minimizing the effects of stress during eyestalk ablation of Litopenaeus vannamei females with topical anesthetic and a coagulating agent. Aquaculture. 233 (1-4), 173-179 (2004).

- Wang, M., Ye, H., Miao, L., Li, X. Role of short neuropeptide F in regulating eyestalk neuroendocrine systems in the mud crab Scylla paramamosain. Aquaculture. 560, 738493 (2022).

- Nagaraju, G. P. C. Reproductive regulators in decapod crustaceans: an overview. Journal of Experimental Biology. 214 (1), 3-16 (2011).

- Kornthong, N., et al. Characterization of red pigment concentrating hormone (RPCH) in the female mud crab (Scylla olivacea) and the effect of 5-HT on its expression. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 185, 28-36 (2013).

- Kornthong, N., et al. Molecular characterization of a vitellogenesis-inhibiting hormone (VIH) in the mud crab (Scylla olivacea) and temporal changes in abundances of VIH mRNA transcripts during ovarian maturation and following neurotransmitter administration. Animal Reproduction Science. 208, 106122 (2019).

- Liu, C., et al. VIH from the mud crab is specifically expressed in the eyestalk and potentially regulated by transactivator of Sox9/Oct4/Oct1. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 255, 1-11 (2018).

- Chen, H. -. Y., Kang, B. J., Sultana, Z., Wilder, M. N. Variation of protein kinase C-α expression in eyestalk removal-activated ovaries in whiteleg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 237 (300), 110552 (2019).

- Rotllant, G., Nguyen, T. V., Aizen, J., Suwansa-ard, S., Ventura, T. Toward the identification of female gonad-stimulating factors in crustaceans. Hydrobiologia. 825 (1), 91-119 (2018).

- Supriya, N. T., Sudha, K., Krishnakumar, V., Anilkumar, G. Molt and reproduction enhancement together with hemolymph ecdysteroid elevation under eyestalk ablation in the female fiddler crab, Uca triangularis (Brachyura: Decapoda). Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology. 35 (3), 645-657 (2017).

- Wilder, M. N. Advances in the science of crustacean reproductive physiology and potential applications to new seed production technology. Journal of Coastal Research. 86 (sp1), 6-10 (2019).

- Arcos, G. F., Ibarra, A. M., Vazquez-Boucard, C., Palacios, E., Racotta, I. S. Haemolymph metabolic variables in relation to eyestalk ablation and gonad development of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei Boone. Aquaculture Research. 34 (9), 749-755 (2003).

- Desai, U. M., Achuthankutty, C. T. Complete regeneration of ablated eyestalk in penaeid prawn, Penaeus monodon. Current Science. 79 (11), 1602-1603 (2000).

- Wu, Q., et al. Growth performance and biochemical composition dynamics of ovary, hepatopancreas and muscle tissues at different ovarian maturation stages of female mud crab, Scylla paramamosain. Aquaculture. 515, 734560 (2020).

- Ghazali, A., Azra, M. N., Noordin, N. M., Abol-Munafi, A. B., Ikhwanuddin, M. Ovarian morphological development and fatty acids profile of mud crab (Scylla olivacea) fed with various diets. Aquaculture. 468 (Part 1), 45-52 (2017).

- Farhadi, A., et al. The regulatory mechanism of sexual development in decapod crustaceans. Frontiers in Marine Science. 8, (2021).

- Sukardi, P., Prayogo, N. A., Harisam, T., Sudaryono, A. Effect of eyestalk-ablation and differences salinity in rearing pond on molting speed of Scylla serrata. AIP Conference Proceedings. 2094, 020029 (2019).

- Stella, V. S., López Greco, L. S., Rodríguez, E. M. Effects of eyestalk ablation at different times of the year on molting and reproduction of the estuarine grapsid crab Chasmagnathus granulata (Decapoda, Brachyura). Journal of Crustacean Biology. 20 (2), 239-244 (2000).

- Jang, I. K., et al. The effects of manipulating water temperature, photoperiod, and eyestalk ablation on gonad maturation of the swimming crab, Portunus trituberculatus. Crustaceana. 83 (2), 129-141 (2010).

- Millamena, O. M., Quinitio, E. The effects of diets on reproductive performance of eyestalk ablated and intact mud crab Scylla serrata. Aquaculture. 181 (1-2), 81-90 (2000).

- Zeng, C. Induced out-of-season spawning of the mud crab, Scylla paramamosain (Estampador) and effects of temperature on embryo development. Aquaculture Research. 38 (14), 1478-1485 (2007).

- Rana, S. Eye stalk ablation of freshwater crab, Barytelphusa lugubris: An alternative approach of hormonal induced breeding. International Journal of Pure and Applied Zoology. 6 (3), 30-34 (2018).

- Yi, S. -. K., Lee, S. -. G., Lee, J. -. M. Preliminary study of seed production of the Micronesian mud crab Scylla serrata (Crustacea: Portunidae) in Korea. Ocean and Polar Research. 31 (3), 257-264 (2009).

- Azra, M. N., Abol-Munafi, A. B., Ikhwanuddin, M. A review of broodstock improvement to brachyuran crab: Reproductive performance. International Journal of Aquaculture. 5 (38), 1-10 (2016).

- Archibald, K. E., Scott, G. N., Bailey, K. M., Harms, C. A. 2-phenoxyethanol (2-PE) and tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222) immersion anesthesia of American horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 50 (1), 96-106 (2019).

- Muhd-Farouk, H., Abol-Munafi, A. B., Jasmani, S., Ikhwanuddin, M. Effect of steroid hormones 17α-hydroxyprogesterone and 17α-hydroxypregnenolone on ovary external morphology of orange mud crab, Scylla olivacea. Asian Journal of Cell Biology. 9 (1), 23-28 (2013).

- Muhd-Farouk, H., Jasmani, S., Ikhwanuddin, M. Effect of vertebrate steroid hormones on the ovarian maturation stages of orange mud crab, Scylla olivacea (Herbst, 1796). Aquaculture. 451, 78-86 (2016).

- Ghazali, A., Mat Noordin, N., Abol-Munafi, A. B., Azra, M. N., Ikhwanuddin, M. Ovarian maturation stages of wild and captive mud crab, Scylla olivacea fed with two diets. Sains Malaysiana. 46 (12), 2273-2280 (2017).

- Aaqillah-Amr, M. A., Hidir, A., Noordiyana, M. N., Ikhwanuddin, M. Morphological, biochemical and histological analysis of mud crab ovary and hepatopancreas at different stages of development. Animal Reproduction Science. 195, 274-283 (2018).

- Amin-Safwan, A., Muhd-Farouk, H., Mardhiyyah, M. P., Nadirah, M., Ikhwanuddin, M. Does water salinity affect the level of 17β-estradiol and ovarian physiology of orange mud crab, Scylla olivacea (Herbst, 1796) in captivity. Journal of King Saud University - Science. 31 (4), 827-835 (2019).

- Wu, X., et al. Effect of dietary supplementation of phospholipids and highly unsaturated fatty acids on reproductive performance and offspring quality of Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis (H. Milne-Edwards), female broodstock. Aquaculture. 273 (4), 602-613 (2007).

- Azra, M. N., Ikhwanuddin, M. A review of maturation diets for mud crab genus Scylla broodstock: Present research, problems and future perspective. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 23 (2), 257-267 (2016).

- Maschio Rodrigues, M., López Greco, L. S., de Almeida, L. C. F., Bertini, G. Reproductive performance of Macrobrachium acanthurus (Crustacea, Palaemonidae) females subjected to unilateral eyestalk ablation. Acta Zoologica. 103 (3), 326-334 (2022).

- Zhang, C., et al. Changes in bud morphology, growth-related genes and nutritional status during cheliped regeneration in the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. PLoS One. 13 (12), e0209617 (2018).

- Zhang, C., et al. Hemolymph transcriptome analysis of Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) with intact, left cheliped autotomy and bilateral eyestalk ablation. Fish & Shellfish Immunology. 81, 266-275 (2018).

- Diarte-Plata, G., Sainz-Hernandez, J. C., Aguiñaga-Cruz, J. A., Fierro-Coronado, J. A., Polanco-Torres, A., Puente-Palazuelos, C. Eyestalk ablation procedures to minimize pain in the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium americanum. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 130 (3-4), 172-178 (2012).

- Mirera, D. O., Moksnes, P. O. Comparative performance of wild juvenile mud crab (Scylla serrata) in different culture systems in East Africa: Effect of shelter, crab size and stocking density. Aquaculture International. 23 (1), 155-173 (2015).

- Ut, V. N., Le Vay, L., Nghia, T. T., Hong Hanh, T. T. Development of nursery cultures for the mud crab Scylla paramamosain (Estampador). Aquaculture Research. 38 (14), 1563-1568 (2007).

- Fazhan, H., et al. Limb loss and feeding ability in the juvenile mud crab Scylla olivacea: Implications of limb autotomy for aquaculture practice. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 247, 105553 (2022).

Erratum

Formal Correction: Erratum: Eyestalk Ablation to Increase Ovarian Maturation in Mud Crabs

Posted by JoVE Editors on 5/26/2023. Citeable Link.

An erratum was issued for: Eyestalk Ablation to Increase Ovarian Maturation in Mud Crabs. The Introduction, Protocol, Discussion and References were updated.

The forth sentence in the third paragraph of the Introduction has been updated from:

The eyestalk ablation protocol in this work minimizes stress by using fully sedated crabs and minimizes physical injury to personnel from crab bites.

to:

The eyestalk ablation protocol in this work minimizes stress by using fully anesthetized crabs and minimizes physical injury to personnel from crab bites.

The start of the Protocol has been updated from:

This protocol follows the Malaysian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes outlined by the Laboratory Animal Science Association of Malaysia. The sacrifice of the experimental samples was done according to the National Institutes of Health Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NIH Publications No. 8023, revised 1978). Sexually pre-mature female mud crabs (orange mud crab S. olivacea) were collected from the local market (5°66′62′′N, 102°72′33′′E) at the Setiu Wetlands in Malaysia. The mud crab species was identified based on morphological characteristics1.

to:

This protocol follows the Malaysian Code of Practice for the Care and Use of Animals for Scientific Purposes outlined by the Laboratory Animal Science Association of Malaysia and was approved by the Universiti Malaysia Terengganu's Research Ethics Committee (Animal ethics approval number: UMT/JKEPHMK/2023/96). The sacrifice of the experimental samples was done according to the AVMA Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals: 2020 Edition. Sexually pre-mature female mud crabs (orange mud crab Scylla olivacea) were collected from the local market (5°66′62′′N, 102°72′33′′E) at the Setiu Wetlands in Malaysia. The mud crab species was identified based on morphological characteristics1.

Section 4 of the Protocol has been updated from:

4. Cold-shock anesthesia

- Select sexually mature females with a dark-colored oval-shaped abdominal flap with a CW >86 mm (Figure 1).

- Catch the crabs with a scoop net, and keep them individually in small aquariums for cold shock anesthesia.

- Prepare 2 L of 4 °C to 1 °C seawater (20 ppt) in a transparent plastic aquarium. Maintain the temperature using (−20 °C) ice bags for cold shock anesthesia.

NOTE: Check the temperature with a digital thermometer. - Immerse the crab in the 4 °C seawater until sedated (about 3−5 min).

- Ensure the crabs are fully anesthetized by the lack of spontaneous movement. The legs and chelipeds joints will still show minor movements when touched with forceps.

to:

4. Anesthesia

- Select sexually mature females with a dark-colored oval-shaped abdominal flap with a CW >86 mm (Figure 1).

- Catch the crabs with a scoop net, and keep them individually in small aquariums for anesthesia.

- After 5 min of acclimatization period, add 2-phenoxyethanol (2-PE) at 2 mL/L into each aquarium and allow 15 min of anesthesia treatment.

- Ensure the crabs are fully anesthetized by the lack of spontaneous movement.

Section 5 of the Protocol has been updated from:

5. Eyestalk ablation

- Cauterization technique

- Perform all procedures on top of a table and in an open area.

- Take a flat head nickel-steel metal rod (e.g., a screwdriver) with a wooden or plastic handle, and cover the handle with a wet cotton towel.

- Sterilize two stainless surgical forceps in an autoclave.

- Prepare 70% ethanol in a spray bottle. Have tissue paper ready for use.

NOTE: Ethanol is highly flammable. Maintain a safe distance from fire sources. - Connect a blowtorch to a gas cylinder (butane) securely.

CAUTION: Follow the instructions on the blowtorch and gas cylinder. Make sure that the blowtorch is switched off when connecting with the gas cylinder. Read and follow all the fire safety precautions mentioned on the gas cylinder. - Wear thick cotton gloves to avoid injury from hot objects.

- Subject the tip of the metal rod to the fire of the blowtorch until the metal rod is bright red.

- Cover the anesthetized (sedated) crab with a wet cotton towel.

NOTE: Cover all the tentacles of the crab to avoid unnecessary damage. - Hold one eye of the crab with sterilized forceps.

NOTE: Sterilize the forceps in an autoclave for first-time use, and disinfect using 70% ethanol for subsequent use on other crabs. - Hold the red-hot metal flat tip onto the eye of the crab and press slightly for about 10−15 s until the eyestalk turns an orange or reddish-orange color.

NOTE: Two people are needed to execute eyestalk ablation following the cauterization method: one to hold the crab and another to perform the ablation procedure. - Disinfect the forceps with 70% ethanol spray to ensure no cross-contamination between crabs.

- After performing the eyestalk ablation on all crabs, dip the hot nickel steel metal rod (screwdriver) into tap water.

- Disinfect the towel before reuse. Multiple towels can be used to save time.

NOTE: Wash the towel with tap water, and dip it into 30 ppm chlorinated water for 5 min. Then, wash the towel with tap water again, and dip it in a 1 g/L sodium thiosulphate solution. - Keep the blowtorch in a safe place after turning it off, and wait until it returns to environmental temperature (about 30 min) before disconnecting.

- Surgery technique

- Perform the procedure in a well-ventilated area.

- Sterilize two surgical scissors and forceps in an autoclave.

- Pour 50 mL of 70% ethanol into a 100 mL glass beaker.

- Prepare the tincture of iodine solution in a dropper bottle.

NOTE: Tincture of iodine (iodine tincture or weak iodine solution) is made up of 2%-7% elemental iodine and potassium iodide, or sodium iodide, dissolved in ethanol and water. - Wear thick cotton gloves.

- Hold the sedated crab, and cover it with a wet cotton towel.

- Hold one eye of the crab with sterilized forceps.

- Swiftly cut off the eyestalk using sterilized surgical scissors.

NOTE: Hemolymph may be lost from the wounded part of the crab. - Dip the scissors and forceps in 70% ethanol after every use, and dry them using tissue paper before reuse.

- Apply two to three drops of iodine tincture to the wounded part of the eyestalk immediately after cutting it off.

NOTE: Tincture of iodine is used for healing and to prevent infection.

to:

5. Eyestalk ablation

- Cauterization technique

- Perform all procedures on top of a table and in an open area.

- Take a flat head nickel-steel metal rod (e.g., a screwdriver) with a wooden or plastic handle, and cover the handle with a wet cotton towel.

- Sterilize two stainless surgical forceps in an autoclave.

- Prepare 70% ethanol in a spray bottle and keep it away from any fire-related sources, such as blow torch and red hot screwdriver. Have tissue paper ready for use.

NOTE: Ethanol is highly flammable. Maintain a safe distance from fire sources. - Connect a blowtorch to a gas cylinder (butane) securely.

CAUTION: Follow the instructions on the blowtorch and gas cylinder. Make sure that the blowtorch is switched off when connecting with the gas cylinder. Read and follow all the fire safety precautions mentioned on the gas cylinder. - Wear thick cotton gloves to avoid injury from hot objects.

- Subject the tip of the metal rod to the fire of the blowtorch until the metal rod is bright red.

- Cover the anesthetized crab with a wet cotton towel.

NOTE: Cover the antennae of the crab to avoid unnecessary damage. - Hold one eye of the crab with sterilized forceps.

NOTE: Sterilize the forceps in an autoclave for first-time use, and disinfect using 70% ethanol for subsequent use on other crabs. - Hold the red-hot metal flat tip onto the eye of the crab and press slightly for about 10−15 s until the eyestalk turns an orange or reddish-orange color. Be careful when conducting this step to avoid damage to adjacent structures.

NOTE: Two people are needed to execute eyestalk ablation following the cauterization method: one to hold the crab and another to perform the ablation procedure. - Disinfect the forceps with 70% ethanol spray to ensure no cross-contamination between crabs.

NOTE: Only perform this step at least waiting for 5 min after the eyestalk ablation procedure to ensure the forceps are cooled down before disinfection using 70% ethanol to prevent potential fire hazards. - After performing the eyestalk ablation on all crabs, dip the hot nickel steel metal rod (screwdriver) into tap water.

- Disinfect the towel before reuse. Multiple towels can be used to save time.

NOTE: Wash the towel with tap water, and dip it into 30 ppm chlorinated water for 5 min. Then, wash the towel with tap water again, and dip it in a 1 g/L sodium thiosulphate solution. - Keep the blowtorch in a safe place after turning it off, and wait until it returns to environmental temperature (about 30 min) before disconnecting.

- Surgery technique

- Perform the procedure in a well-ventilated area.

- Sterilize two surgical scissors and forceps in an autoclave.

- Pour 50 mL of 70% ethanol into a 100 mL glass beaker.

- Wear thick cotton gloves.

- Hold the anesthetized crab, and cover it with a wet cotton towel.

- Hold one eye of the crab with sterilized forceps.

- Swiftly cut off the eyestalk using sterilized surgical scissors.

NOTE: Hemolymph may be lost from the wounded part of the crab. - Dip the scissors and forceps in 70% ethanol after every use, and dry them using tissue paper before reuse.

Step 7.2.2 of the Protocol has been updated from:

Sedate the females individually with the cold shock anesthesia method.

to:

Anesthetize the females individually with the 2-PE immersion anesthesia method.

The Discussion has been updated from:

This protocol was developed for the eyestalk ablation of the mud crab, Scylla spp., and can be applied as an efficient method to induce gonad maturation. This protocol can be easily replicated for the commercial ovary maturation of mud crabs and can be implemented to reduce the latent period (time from one spawning to another) in mud crab seed production.

The eyestalk ablation of crustaceans (i.e., freshwater prawn, marine shrimp) is typically done to induce gonad maturation and out-of-season spawning11,12,13. Eyestalk ablation in brachyuran crabs has also been done to study molting25,32,33, hormonal regulation18, gonad maturation34, and induced breeding and reproductive performance35,36,37,38,39. Unilateral or bilateral eyestalk ablation influences the physiology of the crustacean. Eyestalk ablation following the protocol stated in this study also influences the ovarian maturation rate of mud crabs. In the control treatment (without eyestalk ablation), 43.33% ± 5.77% of female crabs had an immature ovary (stage-1). However, in the same rearing period (30 days), eyestalk-ablated female crabs had pre-maturing ovaries (stage-3; 56.67% ± 11.55% and 53.33% ± 15.28% with the cauterization and surgery techniques, respectively), which shows that eyestalk ablation can increase the gonad maturation of mud crabs. Previous studies have also reported that the ovarian development of intact crabs (without eyestalk ablation) is slower than that of eyestalk-ablated crabs25,31. Due to the slower gonadal development in intact crustaceans, eyestalk ablation is widely done in commercial prawn and shrimp hatcheries. In this protocol, the eyestalk-ablated female crabs achieved higher percentages of ovarian maturation compared to the female crabs without the eyestalk ablation treatment (Figure 3).

The gonad maturation of the mud crab is regulated by hormones21,40,41. The eyestalk contains important endocrine glands (i.e., the X-organ-sinus gland complex) that play vital roles in the gonadal maturation process of mud crabs18,21. Unilateral eyestalk ablation, either by cauterization or surgery, damages one of the major endocrine glands that is involved in the synthesis and release of inhibiting hormones (e.g., VIH), thereby resulting in a higher level of gonad-stimulating hormones (i.e., VSH).

The ovarian maturation stages of Scylla spp. can be differentiated by observing the ovarian tissue coloration with the naked eye29,30,42. Translucent or creamy white ovarian tissues are indications of immature ovaries29,30,42,43. In this study, immature ovaries (stage-1) were still found in the group of female crabs without eyestalk ablation due to the slower ovarian maturation process. However, the crabs in the eyestalk-ablated groups (both by the cauterization and surgery techniques) mostly showed pre-maturing ovaries (stage-3), with some individuals exhibiting fully matured ovaries (stage-4). Therefore, the protocol of eyestalk ablation described here can be used to increase ovarian maturation in female mud crabs. This protocol can also be applied directly to wild-collected mature female mud crabs to hasten their seed production. To evaluate the effectiveness of cauterization and surgery methods on mud crab gonad maturation and to ensure the accurate estimation of molting duration, sexually pre-mature crabs were used. After the (induced) molting of sexually pre-mature female crabs, we noticed that their ovaries were still in the immature or early developing stages29,44. After 30 days of rearing the newly mature female crabs (either eyestalk-ablated or without eyestalk ablation), the ovarian development stages (stage-1 to stage-4) were determined by the color of the ovarian tissues. This protocol encourages the use of the cauterization technique to perform eyestalk ablation in mud crabs to avoid any hemolymph loss and prevent infection at the ablated sites. Cauterization immediately seals the wound, whereas the surgery technique requires an additional step of disinfection using iodine. For commercial purposes, larger mature crabs, preferably at a later stage of ovarian maturation, should be selected for eyestalk ablation to shorten the time to reach the fully matured ovary stage for subsequent commerce or brood stock culture. In addition to eyestalk ablation, individual rearing with sand substrate and sufficient feeding, preferably with live feed, can increase the gonad maturation rate of mud crabs in captivity30,35,45,46.

Crustacean blood is called hemolymph and can be lost during eyestalk ablation. An excessive loss of hemolymph may lead to the death of eyestalk-ablated crabs, especially when performing surgery to remove the eyestalk. The hemolymph can coagulate in the wounded part to prevent loss. The application of a tincture of iodine can prevent infection of the wounded part. However, in comparison to the surgery technique, the cauterization technique seals the wounded part immediately, thereby preventing the loss of hemolymph and possible infection.

Mud crab mortality after unilateral eyestalk ablation with either cauterization or surgery was not found within the first 7 days. Thus, eyestalk ablation can be done with a higher survival rate. Unilateral eyestalk ablation does not hamper the survival rate of the crab33.

Stress during crab handling and eyestalk ablation may contribute to crab mortality. Proper anesthesia is needed to minimize handling stress during eyestalk ablation. In crustacean eyestalk ablation, chemical anesthetics (i.e., xylocaine, lidocaine) are used at the base of the eyestalk before eyestalk ablation14,15,17,47. However, due to the aggressive nature and large size of mud crabs, the use of anesthesia only at the base of the eyestalk is not sufficient and might result in additional stress to the animals during the injection. On the other hand, anesthesia by subjecting them to a lower water temperature is more economical and safer. The use of cold water for anesthesia in mud crabs is common and has been used in other studies due to its efficiency, simplicity, and minimal impact on recovery and survival37,48,49.

Although eyestalk ablation using both cauterization and surgery methods has a minimal effect on crab survival and enhances ovarian maturation, performing eyestalk ablation requires professional mastery of the techniques. The timing between the steps is critical as any delay between protocols adds additional stress for the crabs. Unlike the surgery technique, the cauterization technique is dangerous because it involves the use of flammable equipment (i.e., a blow torch and butane gas). Thus, extra caution is needed when performing the cauterization technique.

Crabs are cannibalistic in nature, and they are known to prey on others that have just completed their molt and are still in their soft-shell conditions7,50,51. Thus, rearing the crabs individually can avoid unnecessary mortality due to cannibalism. The use of individual rearing in mud crab culture is commonly practiced, both in high-density culture and pond culture, for fattening and soft-shell crab farming purposes8,52. This protocol also utilized individual rearing and maintenance. During the transportation of the crabs for rearing or commerce, the crab chelipeds are tied up securely (or even autotomized) to prevent fighting, unnecessary injury, and limb loss34.

The described protocol for eyestalk ablation should be performed with multiple persons. After completing the eyestalk ablation, non-disposable equipment (e.g., the aquarium, tray, towel, etc.) should be disinfected with 30 ppm chlorine. The crabs must be monitored at least twice per day. Any dead crabs, uneaten feed, ablated limbs, or molted crab shells should be swiftly disposed of (i.e., buried in soil with bleaching powder) to prevent any potential for disease spread.

to:

This protocol was developed for the eyestalk ablation of the mud crab, Scylla spp., and can be applied as an efficient method to induce gonad maturation. This protocol can be easily replicated for the commercial ovary maturation of mud crabs and can be implemented to reduce the latent period (time from one spawning to another) in mud crab seed production.

The eyestalk ablation of crustaceans (i.e., freshwater prawn, marine shrimp) is typically done to induce gonad maturation and out-of-season spawning11,12,13. Eyestalk ablation in brachyuran crabs has also been done to study molting25,32,33, hormonal regulation18, gonad maturation34, and induced breeding and reproductive performance35,36,37,38,39. Anesthesia via immersion in 2-phenoxyethanol was used as it is comparable to the use of tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222) in arthopods but cheaper and does not require the use of additional buffer40. Unilateral or bilateral eyestalk ablation influences the physiology of the crustacean. Eyestalk ablation following the protocol stated in this study also influences the ovarian maturation rate of mud crabs. In the control treatment (without eyestalk ablation), 43.33% ± 5.77% of female crabs had an immature ovary (stage-1). However, in the same rearing period (30 days), eyestalk-ablated female crabs had pre-maturing ovaries (stage-3; 56.67% ± 11.55% and 53.33% ± 15.28% with the cauterization and surgery techniques, respectively), which shows that eyestalk ablation can increase the gonad maturation of mud crabs. Previous studies have also reported that the ovarian development of intact crabs (without eyestalk ablation) is slower than that of eyestalk-ablated crabs25,31. Due to the slower gonadal development in intact crustaceans, eyestalk ablation is widely done in commercial prawn and shrimp hatcheries. In this protocol, the eyestalk-ablated female crabs achieved higher percentages of ovarian maturation compared to the female crabs without the eyestalk ablation treatment (Figure 3).

The gonad maturation of the mud crab is regulated by hormones21,41,42. The eyestalk contains important endocrine glands (i.e., the X-organ-sinus gland complex) that play vital roles in the gonadal maturation process of mud crabs18,21. Unilateral eyestalk ablation, either by cauterization or surgery, damages one of the major endocrine glands that is involved in the synthesis and release of inhibiting hormones (e.g., VIH), thereby resulting in a higher level of gonad-stimulating hormones (i.e., VSH).

The ovarian maturation stages of Scylla spp. can be differentiated by observing the ovarian tissue coloration with the naked eye29,30,43. Translucent or creamy white ovarian tissues are indications of immature ovaries29,30,43,44. In this study, immature ovaries (stage-1) were still found in the group of female crabs without eyestalk ablation due to the slower ovarian maturation process. However, the crabs in the eyestalk-ablated groups (both by the cauterization and surgery techniques) mostly showed pre-maturing ovaries (stage-3), with some individuals exhibiting fully matured ovaries (stage-4). Therefore, the protocol of eyestalk ablation described here can be used to increase ovarian maturation in female mud crabs. This protocol can also be applied directly to wild-collected mature female mud crabs to hasten their seed production. To evaluate the effectiveness of cauterization and surgery methods on mud crab gonad maturation and to ensure the accurate estimation of molting duration, sexually pre-mature crabs were used. After the (induced) molting of sexually pre-mature female crabs, we noticed that their ovaries were still in the immature or early developing stages29,45. After 30 days of rearing the newly mature female crabs (either eyestalk-ablated or without eyestalk ablation), the ovarian development stages (stage-1 to stage-4) were determined by the color of the ovarian tissues. This protocol encourages the use of the cauterization technique to perform eyestalk ablation in mud crabs to avoid any hemolymph loss and prevent infection at the ablated sites. Cauterization immediately seals the wound, whereas the surgery technique takes time for the wound to heal and this would allow for chance of infection. For commercial purposes, larger mature crabs, preferably at a later stage of ovarian maturation, should be selected for eyestalk ablation to shorten the time to reach the fully matured ovary stage for subsequent commerce or brood stock culture. In addition to eyestalk ablation, individual rearing with sand substrate and sufficient feeding, preferably with live feed, can increase the gonad maturation rate of mud crabs in captivity30,35,46,47.

Crustacean blood is called hemolymph and can be lost during eyestalk ablation. An excessive loss of hemolymph may lead to the death of eyestalk-ablated crabs, especially when performing surgery to remove the eyestalk. The hemolymph can coagulate in the wounded part to prevent loss. However, in comparison to the surgery technique, the cauterization technique seals the wounded part immediately, thereby preventing the loss of hemolymph and possible infection.

Mud crab mortality after unilateral eyestalk ablation with either cauterization or surgery was not found within the first 7 days. Thus, eyestalk ablation can be done with a higher survival rate. Unilateral eyestalk ablation does not hamper the survival rate of the crab33.

Stress during crab handling and eyestalk ablation may contribute to crab mortality. Proper anesthesia is needed to minimize handling stress during eyestalk ablation. In crustacean eyestalk ablation, chemical anesthetics (i.e., xylocaine, lidocaine) are used at the base of the eyestalk before eyestalk ablation14,15,17,48. However, due to the aggressive nature and large size of mud crabs, the use of anesthesia only at the base of the eyestalk is not sufficient and might result in additional stress to the animals during the injection. On the other hand, anesthesia by subjecting them to a lower water temperature is more economical and safer. The use of cold water for anesthesia in mud crabs is common and has been used in other studies due to its efficiency, simplicity, and minimal impact on recovery and survival37,49,50. In addition, future research on pain assessment following eyestalk ablation on mud crabs is recommended to highlight the change in behaviours associated with pain and stress, as evident in freshwater prawn Macrobrachium americanum51.

Although eyestalk ablation using both cauterization and surgery methods has a minimal effect on crab survival and enhances ovarian maturation, performing eyestalk ablation requires professional mastery of the techniques. The timing between the steps is critical as any delay between protocols adds additional stress for the crabs. Unlike the surgery technique, the cauterization technique is dangerous because it involves the use of flammable equipment (i.e., a blow torch and butane gas). Thus, extra caution is needed when performing the cauterization technique.

Crabs are cannibalistic in nature, and they are known to prey on others that have just completed their molt and are still in their soft-shell conditions7,52,53. Thus, rearing the crabs individually can avoid unnecessary mortality due to cannibalism. The use of individual rearing in mud crab culture is commonly practiced, both in high-density culture and pond culture, for fattening and soft-shell crab farming purposes8,53. This protocol also utilized individual rearing and maintenance. During the transportation of the crabs for rearing or commerce, the crab chelipeds are tied up securely (or even autotomized) to prevent fighting, unnecessary injury, and limb loss34.

The described protocol for eyestalk ablation should be performed with multiple persons. After completing the eyestalk ablation, non-disposable equipment (e.g., the aquarium, tray, towel, etc.) should be disinfected with 30 ppm chlorine. The crabs must be monitored at least twice per day. Any dead crabs, uneaten feed, ablated limbs, or molted crab shells should be swiftly disposed of (i.e., buried in soil with bleaching powder) to prevent any potential for disease spread.

The References have been updated from:

- Keenan, C. P., Davie, P. J. F., Mann, D. L. A revision of the genus Scylla de Haan, 1833 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Portunidae). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 46 (1), 217-245 (1998).

- Fazhan, H. et al. Morphological descriptions and morphometric discriminant function analysis reveal an additional four groups of Scylla spp. PeerJ. 8, e8066 (2020).

- Ikhwanuddin, M., Bachok, Z., Hilmi, M. G., Azmie, G., Zakaria, M. Z. Species diversity, carapace width-body weight relationship, size distribution and sex ratio of mud crab, genus Scylla from Setiu Wetlands of Terengganu coastal waters, Malaysia. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management. 5 (2), 97-109 (2010).

- Ikhwanuddin, M., Bachok, Z., Mohd Faizal, W. W. Y., Azmie, G., Abol-Munafi, A. B. Size of maturity of mud crab Scylla olivacea (Herbst, 1796) from mangrove areas of Terengganu coastal waters. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management. 5 (2), 134-147 (2010).

- Waiho, K. et al. On types of sexual maturity in brachyurans, with special reference to size at the onset of sexual maturity. Journal of Shellfish Research. 36 (3), 807-839 (2017).

- Mykles, D. L., Chang, E. S. Hormonal control of the crustacean molting gland: Insights from transcriptomics and proteomics. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 294, 113493 (2020).

- Fujaya, Y. et al. Is limb autotomy really efficient compared to traditional rearing in soft-shell crab (Scylla olivacea) production? Aquaculture Reports. 18, 100432 (2020).

- Waiho, K. et al. Moult induction methods in soft-shell crab production. Aquaculture Research. 52 (9), 4026-4042 (2021).

- Rahman, M. R. et al. Evaluation of limb autotomy as a promising strategy to improve production performances of mud crab (Scylla olivacea) in the soft-shell farming system. Aquaculture Research. 51 (6), 2555-2572 (2020).

- Okumura, T. et al. Expression of vitellogenin and cortical rod proteins during induced ovarian development by eyestalk ablation in the kuruma prawn, Marsupenaeus japonicus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 143 (2), 246-253 (2006).

- Pervaiz, P. A., Jhon, S. M., Sikdar-bar, M. Studies on the effect of unilateral eyestalk ablation in maturation of gonads of a freshwater prawn Macrobrachium dayanum. World Journal of Zoology. 6 (2), 159-163 (2011).

- Primavera, J. H. Induced maturation and spawning in five-month-old Penaeus monodon Fabricius by eyestalk ablation. Aquaculture. 13 (4), 355-359 (1978).

- Shyne Anand, P. S. et al. Reproductive performance of wild brooders of Indian white shrimp, Penaeus indicus: Potential and challenges for selective breeding program. Journal of Coastal Research. 86 (sp1), 65 (2019).

- Diarte-Plata, G. et al. Eyestalk ablation procedures to minimize pain in the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium americanum. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 140 (3-4), 172-178 (2012).

- Vargas-Téllez, I. et al. Impact of unilateral eyestalk ablation on Callinectes arcuatus (Ordway, 1863) under laboratory conditions: Behavioral evaluation. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research. 49 (4), 576-594 (2021).

- Chu, K. H., Chow, W. K. Effects of unilateral versus bilateral eyestalk ablation on molting and growth of the shrimp, Penaeus chinensis (Osbeck, 1765) (Decapoda, Penaeidea). Crustaceana. 62 (3), 225-233 (1992).

- Taylor, J. Minimizing the effects of stress during eyestalk ablation of Litopenaeus vannamei females with topical anesthetic and a coagulating agent. Aquaculture. 233 (1-4), 173-179 (2004).

- Wang, M., Ye, H., Miao, L., Li, X. Role of short neuropeptide F in regulating eyestalk neuroendocrine systems in the mud crab Scylla paramamosain. Aquaculture. 560, 738493 (2022).

- Nagaraju, G. P. C. Reproductive regulators in decapod crustaceans: an overview. Journal of Experimental Biology. 214 (1), 3-16 (2011).

- Kornthong, N. et al. Characterization of red pigment concentrating hormone (RPCH) in the female mud crab (Scylla olivacea) and the effect of 5-HT on its expression. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 185, 28-36 (2013).

- Kornthong, N. et al. Molecular characterization of a vitellogenesis-inhibiting hormone (VIH) in the mud crab (Scylla olivacea) and temporal changes in abundances of VIH mRNA transcripts during ovarian maturation and following neurotransmitter administration. Animal Reproduction Science. 208, 106122 (2019).

- Liu, C. et al. VIH from the mud crab is specifically expressed in the eyestalk and potentially regulated by transactivator of Sox9/Oct4/Oct1. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 255, 1-11 (2018).

- Chen, H.-Y., Kang, B. J., Sultana, Z., Wilder, M. N. Variation of protein kinase C-α expression in eyestalk removal-activated ovaries in whiteleg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 237 (300), 110552 (2019).

- Rotllant, G., Nguyen, T. V., Aizen, J., Suwansa-ard, S., Ventura, T. Toward the identification of female gonad-stimulating factors in crustaceans. Hydrobiologia. 825 (1), 91-119 (2018).

- Supriya, N. T., Sudha, K., Krishnakumar, V., Anilkumar, G. Molt and reproduction enhancement together with hemolymph ecdysteroid elevation under eyestalk ablation in the female fiddler crab, Uca triangularis (Brachyura: Decapoda). Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology. 35 (3), 645-657 (2017).

- Wilder, M. N. Advances in the science of crustacean reproductive physiology and potential applications to new seed production technology. Journal of Coastal Research. 86 (sp1), 6-10 (2019).

- Arcos, G. F., Ibarra, A. M., Vazquez-Boucard, C., Palacios, E., Racotta, I. S. Haemolymph metabolic variables in relation to eyestalk ablation and gonad development of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei Boone. Aquaculture Research. 34 (9), 749-755 (2003).

- Desai, U. M., Achuthankutty, C. T. Complete regeneration of ablated eyestalk in penaeid prawn, Penaeus monodon. Current Science. 79 (11), 1602-1603 (2000).

- Wu, Q. et al. Growth performance and biochemical composition dynamics of ovary, hepatopancreas and muscle tissues at different ovarian maturation stages of female mud crab, Scylla paramamosain. Aquaculture. 515, 734560 (2020).

- Ghazali, A., Azra, M. N., Noordin, N. M., Abol-Munafi, A. B., Ikhwanuddin, M. Ovarian morphological development and fatty acids profile of mud crab (Scylla olivacea) fed with various diets. Aquaculture. 468 (Part 1), 45-52 (2017).

- Farhadi, A. et al. The regulatory mechanism of sexual development in decapod crustaceans. Frontiers in Marine Science. 8 (2021).

- Sukardi, P., Prayogo, N. A., Harisam, T., Sudaryono, A. Effect of eyestalk-ablation and differences salinity in rearing pond on molting speed of Scylla serrata. AIP Conference Proceedings. 2094, 020029 (2019).

- Stella, V. S., López Greco, L. S., Rodríguez, E. M. Effects of eyestalk ablation at different times of the year on molting and reproduction of the estuarine grapsid crab Chasmagnathus granulata (Decapoda, Brachyura). Journal of Crustacean Biology. 20 (2), 239-244 (2000).

- Jang, I. K. et al. The effects of manipulating water temperature, photoperiod, and eyestalk ablation on gonad maturation of the swimming crab, Portunus trituberculatus.Crustaceana. 83 (2), 129-141 (2010).

- Millamena, O. M., Quinitio, E. The effects of diets on reproductive performance of eyestalk ablated and intact mud crab Scylla serrata. Aquaculture. 181 (1-2), 81-90 (2000).

- Zeng, C. Induced out-of-season spawning of the mud crab, Scylla paramamosain (Estampador) and effects of temperature on embryo development. Aquaculture Research. 38 (14), 1478-1485 (2007).

- Rana, S. Eye stalk ablation of freshwater crab, Barytelphusa lugubris: An alternative approach of hormonal induced breeding. International Journal of Pure and Applied Zoology. 6 (3), 30-34 (2018).

- Yi, S.-K., Lee, S.-G., Lee, J.-M. Preliminary study of seed production of the Micronesian mud crab Scylla serrata (Crustacea: Portunidae) in Korea. Ocean and Polar Research. 31 (3), 257-264 (2009).

- Azra, M. N., Abol-Munafi, A. B., Ikhwanuddin, M. A review of broodstock improvement to brachyuran crab: Reproductive performance. International Journal of Aquaculture. 5 (38), 1-10 (2016).

- Muhd-Farouk, H., Abol-Munafi, A. B., Jasmani, S., Ikhwanuddin, M. Effect of steroid hormones 17α-hydroxyprogesterone and 17α-hydroxypregnenolone on ovary external morphology of orange mud crab, Scylla olivacea. Asian Journal of Cell Biology. 9 (1), 23-28 (2013).

- Muhd-Farouk, H., Jasmani, S., Ikhwanuddin, M. Effect of vertebrate steroid hormones on the ovarian maturation stages of orange mud crab, Scylla olivacea (Herbst, 1796). Aquaculture. 451, 78-86 (2016).

- Ghazali, A., Mat Noordin, N., Abol-Munafi, A. B., Azra, M. N., Ikhwanuddin, M. Ovarian maturation stages of wild and captive mud crab, Scylla olivacea fed with two diets. Sains Malaysiana. 46 (12), 2273-2280 (2017).

- Aaqillah-Amr, M. A., Hidir, A., Noordiyana, M. N., Ikhwanuddin, M. Morphological, biochemical and histological analysis of mud crab ovary and hepatopancreas at different stages of development. Animal Reproduction Science. 195, 274-283 (2018).

- Amin-Safwan, A., Muhd-Farouk, H., Mardhiyyah, M. P., Nadirah, M., Ikhwanuddin, M. Does water salinity affect the level of 17β-estradiol and ovarian physiology of orange mud crab, Scylla olivacea (Herbst, 1796) in captivity? Journal of King Saud University - Science. 31 (4), 827-835 (2019).

- Wu, X. et al. Effect of dietary supplementation of phospholipids and highly unsaturated fatty acids on reproductive performance and offspring quality of Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis (H. Milne-Edwards), female broodstock. Aquaculture. 273 (4), 602-613 (2007).

- Azra, M. N., Ikhwanuddin, M. A review of maturation diets for mud crab genus Scylla broodstock: Present research, problems and future perspective. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 23 (2), 257-267 (2016).

- Maschio Rodrigues, M., López Greco, L. S., de Almeida, L. C. F., Bertini, G. Reproductive performance of Macrobrachium acanthurus (Crustacea, Palaemonidae) females subjected to unilateral eyestalk ablation. Acta Zoologica. 103 (3), 326-334 (2022).

- Zhang, C. et al. Changes in bud morphology, growth-related genes and nutritional status during cheliped regeneration in the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. PLoS One. 13 (12), e0209617 (2018).

- Zhang, C. et al. Hemolymph transcriptome analysis of Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) with intact, left cheliped autotomy and bilateral eyestalk ablation. Fish & Shellfish Immunology. 81, 266-275 (2018).

- Mirera, D. O., Moksnes, P. O. Comparative performance of wild juvenile mud crab (Scylla serrata) in different culture systems in East Africa: Effect of shelter, crab size and stocking density. Aquaculture International. 23 (1), 155-173 (2015).

- Ut, V. N., Le Vay, L., Nghia, T. T., Hong Hanh, T. T. Development of nursery cultures for the mud crab Scylla paramamosain (Estampador). Aquaculture Research. 38 (14), 1563-1568 (2007).

- Fazhan, H. et al. Limb loss and feeding ability in the juvenile mud crab Scylla olivacea: Implications of limb autotomy for aquaculture practice. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 247, 105553 (2022).

to:

- Keenan, C. P., Davie, P. J. F., Mann, D. L. A revision of the genus Scylla de Haan, 1833 (Crustacea: Decapoda: Brachyura: Portunidae). Raffles Bulletin of Zoology. 46 (1), 217-245 (1998).

- Fazhan, H. et al. Morphological descriptions and morphometric discriminant function analysis reveal an additional four groups of Scylla spp. PeerJ. 8, e8066 (2020).

- Ikhwanuddin, M., Bachok, Z., Hilmi, M. G., Azmie, G., Zakaria, M. Z. Species diversity, carapace width-body weight relationship, size distribution and sex ratio of mud crab, genus Scylla from Setiu Wetlands of Terengganu coastal waters, Malaysia. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management. 5 (2), 97-109 (2010).

- Ikhwanuddin, M., Bachok, Z., Mohd Faizal, W. W. Y., Azmie, G., Abol-Munafi, A. B. Size of maturity of mud crab Scylla olivacea (Herbst, 1796) from mangrove areas of Terengganu coastal waters. Journal of Sustainability Science and Management. 5 (2), 134-147 (2010).

- Waiho, K. et al. On types of sexual maturity in brachyurans, with special reference to size at the onset of sexual maturity. Journal of Shellfish Research. 36 (3), 807-839 (2017).

- Mykles, D. L., Chang, E. S. Hormonal control of the crustacean molting gland: Insights from transcriptomics and proteomics. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 294, 113493 (2020).

- Fujaya, Y. et al. Is limb autotomy really efficient compared to traditional rearing in soft-shell crab (Scylla olivacea) production? Aquaculture Reports. 18, 100432 (2020).

- Waiho, K. et al. Moult induction methods in soft-shell crab production. Aquaculture Research. 52 (9), 4026-4042 (2021).

- Rahman, M. R. et al. Evaluation of limb autotomy as a promising strategy to improve production performances of mud crab (Scylla olivacea) in the soft-shell farming system. Aquaculture Research. 51 (6), 2555-2572 (2020).

- Okumura, T. et al. Expression of vitellogenin and cortical rod proteins during induced ovarian development by eyestalk ablation in the kuruma prawn, Marsupenaeus japonicus. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 143 (2), 246-253 (2006).

- Pervaiz, P. A., Jhon, S. M., Sikdar-bar, M. Studies on the effect of unilateral eyestalk ablation in maturation of gonads of a freshwater prawn Macrobrachium dayanum. World Journal of Zoology. 6 (2), 159-163 (2011).

- Primavera, J. H. Induced maturation and spawning in five-month-old Penaeus monodon Fabricius by eyestalk ablation. Aquaculture. 13 (4), 355-359 (1978).

- Shyne Anand, P. S. et al. Reproductive performance of wild brooders of Indian white shrimp, Penaeus indicus: Potential and challenges for selective breeding program. Journal of Coastal Research. 86 (sp1), 65 (2019).

- Diarte-Plata, G. et al. Eyestalk ablation procedures to minimize pain in the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium americanum. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 140 (3-4), 172-178 (2012).

- Vargas-Téllez, I. et al. Impact of unilateral eyestalk ablation on Callinectes arcuatus (Ordway, 1863) under laboratory conditions: Behavioral evaluation. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research. 49 (4), 576-594 (2021).

- Chu, K. H., Chow, W. K. Effects of unilateral versus bilateral eyestalk ablation on molting and growth of the shrimp, Penaeus chinensis (Osbeck, 1765) (Decapoda, Penaeidea). Crustaceana. 62 (3), 225-233 (1992).

- Taylor, J. Minimizing the effects of stress during eyestalk ablation of Litopenaeus vannamei females with topical anesthetic and a coagulating agent. Aquaculture. 233 (1-4), 173-179 (2004).

- Wang, M., Ye, H., Miao, L., Li, X. Role of short neuropeptide F in regulating eyestalk neuroendocrine systems in the mud crab Scylla paramamosain. Aquaculture. 560, 738493 (2022).

- Nagaraju, G. P. C. Reproductive regulators in decapod crustaceans: an overview. Journal of Experimental Biology. 214 (1), 3-16 (2011).

- Kornthong, N. et al. Characterization of red pigment concentrating hormone (RPCH) in the female mud crab (Scylla olivacea) and the effect of 5-HT on its expression. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 185, 28-36 (2013).

- Kornthong, N. et al. Molecular characterization of a vitellogenesis-inhibiting hormone (VIH) in the mud crab (Scylla olivacea) and temporal changes in abundances of VIH mRNA transcripts during ovarian maturation and following neurotransmitter administration. Animal Reproduction Science. 208, 106122 (2019).

- Liu, C. et al. VIH from the mud crab is specifically expressed in the eyestalk and potentially regulated by transactivator of Sox9/Oct4/Oct1. General and Comparative Endocrinology. 255, 1-11 (2018).

- Chen, H.-Y., Kang, B. J., Sultana, Z., Wilder, M. N. Variation of protein kinase C-α expression in eyestalk removal-activated ovaries in whiteleg shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei. Comparative Biochemistry and Physiology Part A: Molecular & Integrative Physiology. 237 (300), 110552 (2019).

- Rotllant, G., Nguyen, T. V., Aizen, J., Suwansa-ard, S., Ventura, T. Toward the identification of female gonad-stimulating factors in crustaceans. Hydrobiologia. 825 (1), 91-119 (2018).

- Supriya, N. T., Sudha, K., Krishnakumar, V., Anilkumar, G. Molt and reproduction enhancement together with hemolymph ecdysteroid elevation under eyestalk ablation in the female fiddler crab, Uca triangularis (Brachyura: Decapoda). Chinese Journal of Oceanology and Limnology. 35 (3), 645-657 (2017).

- Wilder, M. N. Advances in the science of crustacean reproductive physiology and potential applications to new seed production technology. Journal of Coastal Research. 86 (sp1), 6-10 (2019).

- Arcos, G. F., Ibarra, A. M., Vazquez-Boucard, C., Palacios, E., Racotta, I. S. Haemolymph metabolic variables in relation to eyestalk ablation and gonad development of Pacific white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei Boone. Aquaculture Research. 34 (9), 749-755 (2003).

- Desai, U. M., Achuthankutty, C. T. Complete regeneration of ablated eyestalk in penaeid prawn, Penaeus monodon. Current Science. 79 (11), 1602-1603 (2000).

- Wu, Q. et al. Growth performance and biochemical composition dynamics of ovary, hepatopancreas and muscle tissues at different ovarian maturation stages of female mud crab, Scylla paramamosain. Aquaculture. 515, 734560 (2020).

- Ghazali, A., Azra, M. N., Noordin, N. M., Abol-Munafi, A. B., Ikhwanuddin, M. Ovarian morphological development and fatty acids profile of mud crab (Scylla olivacea) fed with various diets. Aquaculture. 468 (Part 1), 45-52 (2017).

- Farhadi, A. et al. The regulatory mechanism of sexual development in decapod crustaceans. Frontiers in Marine Science. 8 (2021).

- Sukardi, P., Prayogo, N. A., Harisam, T., Sudaryono, A. Effect of eyestalk-ablation and differences salinity in rearing pond on molting speed of Scylla serrata. AIP Conference Proceedings. 2094, 020029 (2019).

- Stella, V. S., López Greco, L. S., Rodríguez, E. M. Effects of eyestalk ablation at different times of the year on molting and reproduction of the estuarine grapsid crab Chasmagnathus granulata (Decapoda, Brachyura). Journal of Crustacean Biology. 20 (2), 239-244 (2000).

- Jang, I. K. et al. The effects of manipulating water temperature, photoperiod, and eyestalk ablation on gonad maturation of the swimming crab, Portunus trituberculatus.Crustaceana. 83 (2), 129-141 (2010).

- Millamena, O. M., Quinitio, E. The effects of diets on reproductive performance of eyestalk ablated and intact mud crab Scylla serrata. Aquaculture. 181 (1-2), 81-90 (2000).

- Zeng, C. Induced out-of-season spawning of the mud crab, Scylla paramamosain (Estampador) and effects of temperature on embryo development. Aquaculture Research. 38 (14), 1478-1485 (2007).

- Rana, S. Eye stalk ablation of freshwater crab, Barytelphusa lugubris: An alternative approach of hormonal induced breeding. International Journal of Pure and Applied Zoology. 6 (3), 30-34 (2018).

- Yi, S.-K., Lee, S.-G., Lee, J.-M. Preliminary study of seed production of the Micronesian mud crab Scylla serrata (Crustacea: Portunidae) in Korea. Ocean and Polar Research. 31 (3), 257-264 (2009).

- Azra, M. N., Abol-Munafi, A. B., Ikhwanuddin, M. A review of broodstock improvement to brachyuran crab: Reproductive performance. International Journal of Aquaculture. 5 (38), 1-10 (2016).

- Archibald, K. E., Scott, G. N., Bailey, K. M., Harms, C. A. 2-phenoxyethanol (2-PE) and tricaine methanesulfonate (MS-222) immersion anesthesia of American horseshoe crabs (Limulus polyphemus). Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 50 (1), 96-106 (2019).

- Muhd-Farouk, H., Abol-Munafi, A. B., Jasmani, S., Ikhwanuddin, M. Effect of steroid hormones 17α-hydroxyprogesterone and 17α-hydroxypregnenolone on ovary external morphology of orange mud crab, Scylla olivacea. Asian Journal of Cell Biology. 9 (1), 23-28 (2013).

- Muhd-Farouk, H., Jasmani, S., Ikhwanuddin, M. Effect of vertebrate steroid hormones on the ovarian maturation stages of orange mud crab, Scylla olivacea (Herbst, 1796). Aquaculture. 451, 78-86 (2016).

- Ghazali, A., Mat Noordin, N., Abol-Munafi, A. B., Azra, M. N., Ikhwanuddin, M. Ovarian maturation stages of wild and captive mud crab, Scylla olivacea fed with two diets. Sains Malaysiana. 46 (12), 2273-2280 (2017).

- Aaqillah-Amr, M. A., Hidir, A., Noordiyana, M. N., Ikhwanuddin, M. Morphological, biochemical and histological analysis of mud crab ovary and hepatopancreas at different stages of development. Animal Reproduction Science. 195, 274-283 (2018).

- Amin-Safwan, A., Muhd-Farouk, H., Mardhiyyah, M. P., Nadirah, M., Ikhwanuddin, M. Does water salinity affect the level of 17β-estradiol and ovarian physiology of orange mud crab, Scylla olivacea (Herbst, 1796) in captivity? Journal of King Saud University - Science. 31 (4), 827-835 (2019).

- Wu, X. et al. Effect of dietary supplementation of phospholipids and highly unsaturated fatty acids on reproductive performance and offspring quality of Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis (H. Milne-Edwards), female broodstock. Aquaculture. 273 (4), 602-613 (2007).

- Azra, M. N., Ikhwanuddin, M. A review of maturation diets for mud crab genus Scylla broodstock: Present research, problems and future perspective. Saudi Journal of Biological Sciences. 23 (2), 257-267 (2016).

- Maschio Rodrigues, M., López Greco, L. S., de Almeida, L. C. F., Bertini, G. Reproductive performance of Macrobrachium acanthurus (Crustacea, Palaemonidae) females subjected to unilateral eyestalk ablation. Acta Zoologica. 103 (3), 326-334 (2022).

- Zhang, C. et al. Changes in bud morphology, growth-related genes and nutritional status during cheliped regeneration in the Chinese mitten crab, Eriocheir sinensis. PLoS One. 13 (12), e0209617 (2018).

- Zhang, C. et al. Hemolymph transcriptome analysis of Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis) with intact, left cheliped autotomy and bilateral eyestalk ablation. Fish & Shellfish Immunology. 81, 266-275 (2018).

- Diarte-Plata, G., Sainz-Hernandez, J. C., Aguiñaga-Cruz, J. A., Fierro-Coronado, J. A., Polanco-Torres, A., Puente-Palazuelos, C. Eyestalk ablation procedures to minimize pain in the freshwater prawn Macrobrachium americanum. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 140 (3-4), 172-178 (2012).

- Mirera, D. O., Moksnes, P. O. Comparative performance of wild juvenile mud crab (Scylla serrata) in different culture systems in East Africa: Effect of shelter, crab size and stocking density. Aquaculture International. 23 (1), 155-173 (2015).

- Ut, V. N., Le Vay, L., Nghia, T. T., Hong Hanh, T. T. Development of nursery cultures for the mud crab Scylla paramamosain (Estampador). Aquaculture Research. 38 (14), 1563-1568 (2007).

- Fazhan, H. et al. Limb loss and feeding ability in the juvenile mud crab Scylla olivacea: Implications of limb autotomy for aquaculture practice. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 247, 105553 (2022).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionExplore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved