Ostracism: Effects of Being Ignored Over the Internet

Overview

Source: Peter Mende-Siedlecki & Jay Van Bavel—New York University

Social ostracism is defined as being ignored and excluded in the presence of others. This experience is a pervasive and powerful social phenomenon, observed in both animals and humans, throughout all stages of human development, and across all manner of dyadic relationships, cultures, and social groups and institutions. Some have argued that ostracism serves a social regulatory function, which can enhance group cohesion and fitness by removing unwanted elements.1 As such, the feeling of ostracism can serve as a warning to alter one’s behavior, in order to rejoin with the group.2

Research in social psychology has focused extensively on the affective and behavioral consequences of social ostracism. For example, individuals who have been ostracized report feeling depressed, lonely, anxious, frustrated, and helpless,3 and while they may now evaluate the source of their ostracism more negatively, they will also often try to ingratiate themselves to them.2 Furthermore, it has been speculated that the fear of ostracism is ultimately driven by a strong need to belong and to feel included, and serves as a social pressure leading to conformity, compliance, and impression management.4

In a model developed by Williams (1997), ostracism uniquely targets four core needs— belonging, self-esteem, control, and meaningful existence—triggering negative mood, anxiety, physiological arousal, and hurt feelings.5 In return, to defend against such psychological discomfort, ostracized individuals may attempt to cope by reinforcing these core needs. For example, they may attempt to visibly conform to group norms to reestablish their place amongst the collective.

Principles

In the present study, Williams, Cheung, and Choi (2000) developed a novel technique for inducing and studying social ostracism in the laboratory setting. In previous research, participants engaged in an experience of “real-life” ostracism: while playing a five-minute ball-tossing game with confederates, some participants received the ball only a few times towards the beginning of the five-minute period, and then never again.2,6 While this manipulation evoked strong emotional responses of ostracism in participants, the authors decided that it was ultimately an inefficient design, particularly with regards to the roles of the confederates and the training they require. Building on this research, the authors devised a new, computerized version of the ball-tossing task, which became known as Cyberball,3 which is detailed below.

In the design described below, the original authors went to great lengths to characterize the effects of social ostracism on feelings of belonging and conformity, as well as to understand the potentially moderating role of group membership. For example, they included additional conditions designed to serve as experimental controls to ascertain a) participants’ baseline levels of performance, independent of conformity, as well as b) participants’ baseline susceptibility to conformity, independent of exclusion. The latter control allows the experimenter to determine the directionality of the observed effect of exclusion—i.e., does exclusion increase conformity, compared to baseline, or rather, does inclusion decrease conformity? As for the effects of group membership, while these conditions were included in the original study, this manipulation could ultimately be omitted at the experimenter’s discretion, if he or she simply wanted to focus on the impact of social ostracism, independent of group membership.

Procedure

1. Recruiting Participants

- Conduct a power analysis and recruit a sufficient number of participants (approximately 20/group) to cover six different experimental conditions, and, if desired, two additional control conditions (Table 1).

| In-Group | Out-Group | Mixed-Group | ||

| Exclusion | (1) Excluded from a group composed of two in-group members | (2) Excluded from a group composed of two out-group members | (3) Excluded from a group composed of one in-group and one out-group member | |

| Inclusion | (4) Included in a group composed of two in-group members | (5) Included in a group composed of two out-group members | (6) Included in a group composed of one in-group and one out-group member | |

| Additional Control Conditions (if desired) |

(7) Participants complete just the perception task, and perform it alone, to determine baseline performance in that task, independent of conformity (see step 11). | (8) Participants complete just the perception task with group responses, to determine baseline influence of conformity pressure, independent of exclusion or inclusion (see step 11). | ||

2. Data Collection

- Run participants individually.

- Seat the participant in front of a computer that is connected to the internet and open the Cyberball program.

- Instruct the participant that they will be taking part in computerized task, and that they should read the directions carefully.

- Describe the purpose of the experiment as comparing perceptual abilities of PC versus Mac users.

- Inform the participant that they will be interacting with other players who are simultaneously logged onto the study over the internet. Note: The original investigation was performed over the internet, with participants logging in remotely rather than performing the experiment in the laboratory.

- Have each participant sign a consent form to participate.

- Request that participants fill out a pre-experimental questionnaire, in which they are asked to specify which type of computer they typically use (i.e., Mac or PC) and to write brief descriptions of average PC users and average Mac users.

- Use these descriptions later as a manipulation check to determine whether participants make more positive comments about players who used the same type of computer as they do.

- Randomly assign participants to one of the three “strength of group-ties-manipulation” conditions prior to beginning the Cyberball game: in-group, out-group, or mixed-group.

- Specifically, tell participants that the other two players they’ll be interacting with are either a) both PC users, b) both Mac users, or c) one of each. For participants that are PC users, this creates in-group, out-group and mixed-group conditions, respectively. For Mac users, this creates out-group, in-group, and mixed-group conditions, respectively.

- Leave the room once the participant begins the Cyberball game.

- The Cyberball game should be described as a means to an end-specifically, as merely a task that should help participants exercise their mental visualization skills, which they will purportedly use in the subsequent experimental task.

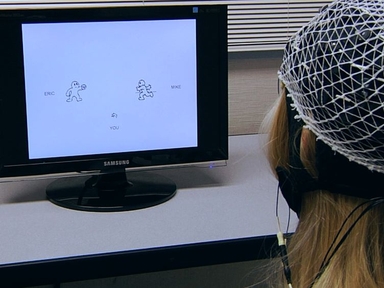

- The game depicts three ball-tossers, the middle one representing the participant. The game is animated and shows the icon throwing a ball to one of the other two. When the ball is tossed to the participant, they are instructed to click on one of the other two icons to indicate their intended recipient, and the ball then moves toward that icon.

- Make sure the Cyberball task is set to randomly assign the participant to one of two “ostracism-manipulation” conditions: inclusion or complete ostracism.

- The program will hold the first three throws of the game constant across all conditions, always starting off with the participant in possession of the ball.

- In the original experiment, the task was set to 10 throws in total. Subsequent versions of the task have increased the number of throws for additional statistical power (e.g., 40 throws).7 If the experimenter has a large enough sample size within each condition, fewer trials are acceptable; however, if not, additional trials are certainly desirable.

- Subsequently, every player is given the chance to throw and catch the ball once.

- On the fourth throw, the participant will once again be in possession of the ball and have the chance to throw it to either of the two computer players.

- From the fifth throw onwards, participants are randomly assigned by a predetermined algorithm to either be included or ostracized.

- If in the in the inclusion condition, the participant will continue to receive the ball for a third of the throws.

- If in the ostracism condition, the participant will not be thrown the ball again.

- The primary dependent variable of Cyberball is participants’ perceptions of the percentage of time they were thrown to.

- The program will hold the first three throws of the game constant across all conditions, always starting off with the participant in possession of the ball.

- To provide insight into how participants might perform on the perception task in absence of ostracism and peer influence, the original authors also ran two sets of control participants that did not perform the Cyberball task, but instead, went straight to the perception task.

- While these control conditions were included in the original research, and offer an additional degree of experimental control, they are not strictly necessary to include. However, to replicate these conditions, follow the instructions below.

- Have one set of control participants skip the Cyberball task, and proceed directly to a version of the perception task which does not include the other five respondents (e.g., so there is no pressure to conform to peer influence).

- Have a second set of control participants also skip the Cyberball task, and proceed directly to the group perception task as described. These data allow the researcher to determine the directionality of their effects (i.e., does ostracism increase conformity, or does inclusion decrease it?).

- While these control conditions were included in the original research, and offer an additional degree of experimental control, they are not strictly necessary to include. However, to replicate these conditions, follow the instructions below.

- After the Cyberball game, re-enter the testing room to launch the second part of the study, which the participant should believe to be the primary experiment-a computerized perception task.

- Instruct them to click a number on the rotating wheel to determine which respondent number they will be assigned.

- The wheel should be rigged to always stop at the No. 6 position, so that all participants are (ostensibly randomly) assigned to be the sixth person in a new, six-person group that will be asked to make judgments regarding six perceptual comparisons.

- Next, provide the participant with an overview of the perception task with a visual example.

- Explain that on each trial, a simple geometric figure (like a triangle) will appear on the screen for 5 s, after which it will disappear, followed by six complex figures that will also be displayed on the screen for 5 s. The initial, simple geometric figure will be embedded in one of the six complex figures.

- Instruct the participant that their task is to identify the correct figure (i.e., the complex figure containing the initial, simple figure) from the six by clicking on the appropriate button.

- Critically, make clear to the participant, that since they are Respondent #6, while waiting for their turn to respond, other users' responses will appear sequentially on the screen.

- When "Respondent Number 6" appears on the screen, have the participant enter their response.

- Once the participant understands the directions, begin the perception task.

- Trials 1 and 2 of the perception task should be easier than the ones that follow, in order to familiarize participants with the demands of the task.

- Trials 3, 4, and 6 are the critical trials of the task. On these trials, the other “players” should be preprogrammed to display unanimously incorrect responses.

- On the other trials (Trials 1, 2, and 5), the other members should make unanimously correct responses.

- The primary dependent variable of the perception task is conformity. Simply calculate the percentage of times that each participant conforms with the unanimous wrong answers provided by the group on Trials 3, 4, and 6.

- Afterwards, ask the participant to complete a post-experimental questionnaire on the computer.

- Make sure this questionnaire contains several manipulation checks, and measures feelings of belonging.

- As a manipulation check, ask participants to report on perceptions of the number of throws they received, as well as whether their co-partners were using a Mac, or PC, or one of each.

- To assess belonging, ask participants to rate the extent to which they felt a sense of belonging with their co-partners on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 9 (very much).

- The primary dependent variable of the questionnaire is feeling of belonging. Average the ratings given by groups.

- Make sure this questionnaire contains several manipulation checks, and measures feelings of belonging.

- Fully debrief the participant regarding the purpose and procedures of the study.

- In particular, explain the ostracism manipulations, the computer-generated partners, and the conformity ruse.

- Provide your contact information to the participant, in case they have further questions or concerns.

3. Data Analysis

- After running all participants, examine how a) participants’ perceptions of the percentage of time they were thrown to (essentially a manipulation check), b) feelings of belonging, and c) conformity vary as a function of both ostracism/inclusion and group composition.

- To do so, perform three separate via 2 (ostracism vs. inclusion) x 3 (group composition: in-group, out-group, mixed group) ANOVAs on these dependent variables.

- In addition, analyze the responses from the pre-experimental questionnaire, via a 2 (group membership: Mac or PC) x 2 (target group: Mac or PC) mixed ANOVA, to confirm that on average, participants rated in-group members more positively than out-group members.

Results

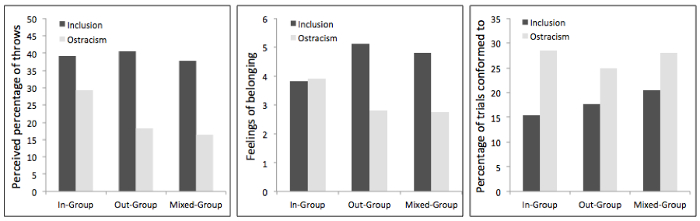

In the original Williams, Cheung, and Choi investigation in 2000, the authors observed strong main effects of ostracism across three key dependent variables. Participants who were ostracized reported receiving fewer throws, reported feeling lower feelings of belonging, and conformed on a higher percentage of trials, compared to participants who were included (Figure 1).

While the effects of group membership were somewhat more mixed, the authors reported two interactions between ostracism and group membership, one concerning the manipulation check and one concerning feelings of belonging. Specifically, individuals in the in-group condition did not show significant differences between perceived throws received between the ostracism and inclusion groups, nor they differ in terms of feelings of belonging. Nevertheless, participants who were ostracized in in-group groups still conformed significantly more than individuals who were included.

Figure 1: Means for three dependent variables (perceived percentage of throws, feelings of belonging, and percentage of trials conformed to) as a function of the type of interaction (inclusion or ostracism) and group memberships (in-group, out-group, and mixed-group). The figure on the left shows that targets of ostracism correctly perceived that they received less throws. Moreover, the figures in the middle and right show that targets of ostracism reported lower feelings of belonging and were more likely to conform to the unanimous incorrect judgments of a new group.

Application and Summary

Based on these results, Williams and colleagues concluded that they had successfully developed a tool for robustly inducing feelings of social ostracism in participants, even without direct face-to-face interaction. Indeed, in their investigation, being excluded over the internet led participants to feel less belonging, and in turn, led participants to conform to the beliefs of a new group of individuals. The authors interpreted this behavior as an attempt to reaffirm feelings of belonging. These results are striking given the relative simplicity of the context of ostracism. Players do not communicate, they cannot see each other, and they have no reason to believe that they will ever interact again. Yet momentary exclusion produces robust affective and behavioral consequences.

Ostracism is a powerful and salient social signal. When we are ostracized, we feel upset, excluded, and unsure of our place in the social hierarchy. As such, we may take steps to restore that place—either by attempting to get back into the good graces of the ostracizer, or by finding new acceptance elsewhere. The Cyberball task represents a robust and efficient means of inducing these feelings experimentally, either through a laboratory set-up, or conducted remotely over the internet.

As the task itself is relatively decontextualized, any number of modifications might be made to any aspect of it (e.g., the instructions, the players, the nature of the ball-tossing interaction) to test various hypotheses. The induction might be used to test various responses to ostracism, both anti-social (e.g., aggression) and pro-social (e.g., ingratiation). The task might be used (and indeed has by some authors) to examine the physiological components8 and neural bases supporting social ostracism.9 Finally, the original authors have suggested that while in its original inception, Cyberball is used to manipulate feelings of ostracism, it might also be used as a dependent measure (e.g., of prejudice or altruism), by focusing on participants’ choices to include or exclude the other players.

References

- Gruter, M., & Masters, R. D. (1986). Ostracism as a social and biological phenomenon: An introduction. Ethology and Sociobiology, 7, 149-158.

- Williams, K. D., & Sommer, K. L. (1997). Social ostracism by coworkers: Does rejection lead to loafing or compensation? Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 693-706.

- Williams, K. D., Cheung, C. K. T., & Choi, W. (2000). Cyberostracism: Effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 79, 748-762.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497-529.

- Williams, K. D. (1997). Social ostracism. In R. Kowalski (Ed.), Aversive interpersonal behaviors (pp. 133-170). New York: Plenum.

- Williams, K. D., & Jarvis, B. (2006). Cyberball: A program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behavior research methods, 38, 174-180.

- Zadro, L., Williams, K. D., & Richardson, R. (2004). How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer is sufficient to lower self-reported levels of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 560-567.

- Kelly, M., McDonald, S., & Rushby, J. (2012). All alone with sweaty palms—Physiological arousal and ostracism. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 83, 309-314.

- Eisenberger, N. I., Lieberman, M. D., & Williams, K. D. (2003). Does rejection hurt? An fMRI study of social exclusion. Science, 302, 290-292.

Skip to...

Videos from this collection:

Now Playing

Ostracism: Effects of Being Ignored Over the Internet

Social Psychology

10.6K Views

Analyzing Situations in Helping Behavior

Social Psychology

41.9K Views

Ostracism: Effects of Being Ignored Over the Internet

Social Psychology

10.6K Views

قياس العصبية والسلوكية آخر الجارية خلال التفاعلات الاجتماعية المحوسبة: دراسة ذات الصلة بالحدث إمكانات الدماغ

Social Psychology

13.7K Views

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved