需要订阅 JoVE 才能查看此. 登录或开始免费试用。

Method Article

海马神经元中突触囊泡吞的测量

摘要

突触囊泡吞是通过光学显微镜检测 pHluorin 融合与突触泡蛋白和电子显微镜的囊泡摄取。

摘要

在吞, 融合突触泡在神经末端被检索, 允许囊泡再循环和因而维持突触传输在重复的神经生火期间。损伤的吞在病理条件下导致突触强度和脑功能下降。在这里, 我们描述的方法用于测量突触囊泡吞在哺乳动物海马突触在神经元培养。我们监测突触囊泡蛋白吞融合的突触囊膜蛋白, 包括突和 VAMP2/synaptobrevin, 在水泡腔侧, 与 pHluorin, pH 敏感的绿色荧光蛋白, 增加其荧光强度随着 pH 值的增加而增大。在胞, 水泡流明 ph 增加, 而在吞水泡流明 ph 值是 re-acidified。因此, pHluorin 荧光强度的增加表明融合, 而减少表明吞的标签突触泡蛋白。除了使用 pHluorin 成像方法记录吞, 我们还通过电子显微镜 (EM) 测量了辣根过氧化物酶 (HRP) 对囊泡的摄取量来监测水泡膜的吞。最后, 在高钾诱导去极化后的不同时间, 我们监测了神经末端膜凹坑的形成。HRP 吸收和膜坑形成的时间过程表明吞的时间过程。

引言

神经递质储存在突触泡中, 由胞释放。突触囊泡膜和蛋白质被吞化, 并在下一轮胞中重复使用。突触囊泡的吞对维持突触囊泡池和从细胞膜上去除突起的泡囊很重要。ph 敏感的绿色荧光蛋白 pHluorin, 这是在酸性情况下淬火和 dequenched 在中性 ph 值, 已被用来测量吞时间课程在活细胞1,2,3。pHluorin 蛋白通常附着在突触囊泡蛋白的腔侧, 如突或 VAMP2/synaptobrevin。在休息, pHluorin 是淬火在 5.5 pH 流明的突触泡。囊泡融合到等离子体膜暴露水泡腔的胞外溶液的 pH 值是〜 7.3, 导致增加 pHluorin 荧光。胞后, 增加的荧光衰变, 由于吞的突触囊泡蛋白, 其次是囊泡 re-acidification 在这些回收泡。虽然衰变反映了吞和水泡 re-acidification, 它主要反映吞, 因为 re-acidification 在大多数情况下比吞快1,4。re-acidification 的时间常数为 3-4 s 或更少的5,6, 它通常比十年代或更多的泡吞4,5所需的速度快。如果需要进行实验来区分吞和 re-acidification, 使用 4-Morpholineethanesulfonic 酸 (MES) 溶液 (25 mM) 和 pH 值为5.5 的酸性淬火实验可以用来确定是否检索突触囊泡蛋白从等离子膜通过吞1,3,4。因此, pHluorin 荧光强度的增加反映了外、吞的平衡, 神经刺激后的减少具体反映了吞。

pHluorin 成像不仅可以用来测量吞的时间过程, 也可用于突触囊泡池的大小7,8, 以及诱发释放和自发释放9的概率。许多因素和蛋白质参与调节吞, 如钙, 可溶性 NSF-附着蛋白受体 (诱捕) 蛋白, 脑源性神经营养因子 (BDNF) 和磷酸已被确定使用 pHluorin 成像1,2,10,11,12,13,14,15,16. 此外, 神经递质的释放不仅可在原发神经元中检测, 而且可以在显微镜17的神经母细胞瘤中发现。最近, pHluorin 变体、dsRed、mOrange 和 pHTomato 被开发用于在单个突触1819中监视多个因素的同时录制。例如, pHTomato 已与突融合, 并与基因编码的钙指示剂 (GCaMP5K) 一起使用, 以监测前囊泡融合, 并在突触后室20中的 Ca2 +流入。因此, pHluorin 附在突触蛋白提供了一个有用的方法来分析吞和胞的关系。

EM 是另一种方法, 通常用于研究吞, 由于高空间分辨率, 显示超微结构的变化, 在吞。两个一般的领域是能够可视化的病理改变神经元细胞21和跟踪囊泡蛋白22。特别是, 观察突触囊泡摄取, 膜曲率涂覆格在 periactive 区, 和内涵结构是可能的 EM3,23,24,25 ,26,27,28。虽然 EM 涉及潜在的文物, 如固定诱发的畸形, 可能会影响吞, 和数据分析是劳动密集型, 该决议提供了一个诱人的机会, 可视化细胞结构。在吞27期间, 可能存在的定影问题和 EM 时间分辨率的限制可以通过高压冻结来克服, 提供一种快速和非化学的方法来稳定当前的微妙结构。

研究方案

注意: 下面的协议描述了在培养海马神经元中使用的 pHluorin 成像方法和 em 方法. pHluorin 监测活细胞中突触囊泡蛋白的摄取和 em 检测突触泡的摄取和超微结构的变化.

动物护理和程序遵循 nih 的指导方针, 并得到了 nih 动物保育和使用委员会的批准.

1. pHluorin 成像

- 海马神经元培养

- 通过组合 4 mm NaHCO 3 和 5 mm HEPES, 并调整到 pH 7.3 与 5 M 氢氧化钠。通过混合 neurobasal 培养基、2% B27、0.5 毫米-l-谷氨酰胺和1% 青霉素-链霉素进行培养基的培养。另外, 准备一个血红蛋白缓冲液与20% 胎牛血清 (HB/20%fbs) 的混合物.

注意: 此培养协议基于 Sankaranarayanan, et al. 29 和 Wu , et al. 24 - 斩首在产后0天到2天之间的小鼠幼崽变成培养基, 并将大脑提取到4和 #176; HB/20%fbs。切除脑干和丘脑以暴露海马。解剖的海马, 后, 揭露它的脑干和丘脑切除, 并转移到新鲜的4和 #176; HB/20%fbs.

注意: 通常, 一个 pup (两个海马) 的收益率大约为 4 x 10 5 单元/mL。用镊子或剪刀清洗附着的膜, 然后转到新鲜的4和 #176; HB/20%fbs。用剪刀切开齿状回, 分离 subiculum, 然后转移到新鲜的4和 #176; C HB/20%fbs. - 将每个海马体从端部切割到10片, 并将其转移到15毫升的聚丙烯锥形管中.

- 在允许组织沉淀后, 用10毫升的 HB/20%fbs 冲洗, 然后用10毫升的 HB 洗涤三次.

- 准备137毫米氯化钠, 5 毫米氯化钾, 7 毫米 Na2HPO 4 和25毫米 HEPES 的消解溶液, 并调整到 pH 7.2 与5米氢氧化钠。从海马中除去清液。添加10毫克的胰蛋白酶和1毫克的 dnasei 到2毫升的消化液, 并通过无菌0.22 和 #181; m 膜直接在样品颗粒上过滤.

- 在37和 #176 孵育海马5分钟, 然后用10毫升的 HB/20%fbs 冲洗两次, 然后用10毫升的 HB 冲洗一次.

- 将单元格与6毫克的 MgSO 4 & #8729; 7H 2 O 和1毫克的 dnasei 到2毫升 HB 和无菌过滤器通过无菌0.22 和 #181; m 过滤器海马颗粒。小心地研制细胞, 同时注意避免引入气泡。让组织微粒沉淀2分钟, 然后慢慢地将上清液转移到另一根管子上.

- 添加3毫升 HB/20%fbs 到细胞悬浮, 离心机或10分钟在4和 #176; C 和 1000 rpm。在培养基中丢弃上清和重.

- 板6万细胞悬浮在150和 #181; L 培养基上的聚 d-赖氨酸涂层25毫米直径片, 没有溢出的片。在电镀后加入2毫升的5ml 培养基2小时。片是保持在6良好的培养皿或无菌的 Petri 盘.

- 在37和 #176 中维护单元格; C 在 5% CO 2 录制前14-21 天在培养基中加湿培养培养基。在文化成长过程中, 每周更换培养基的上半部两次.

- 通过组合 4 mm NaHCO 3 和 5 mm HEPES, 并调整到 pH 7.3 与 5 M 氢氧化钠。通过混合 neurobasal 培养基、2% B27、0.5 毫米-l-谷氨酰胺和1% 青霉素-链霉素进行培养基的培养。另外, 准备一个血红蛋白缓冲液与20% 胎牛血清 (HB/20%fbs) 的混合物.

- 转染

- 电镀后6-7 天, 染突 pHluorin 2X (SpH) 或 VAMP2-pHluorin 进入海马神经元。对于 SpH, 使用巨细胞病毒 (CMV) 启动子, 插入到一个 pcDNA3 矢量 30 。对于 VAMP2-pHluorin, 使用插入到 pCI 向量 31 中的 CMV 启动子. 使用1和 #181; 质粒的 g, 通过脂质载体将载体染到靶细胞中。使用培养基从协议步骤 1.1.1, 缺乏血清, 为转染。在转染后改变培养基2小时以降低毒性.

注: 在 boutons SpH 低表达时, 将 DNA 浓度提高到2和 #181; g 或与脂质载体的潜伏期, 除非细胞不健康。通常, 4-10 细胞 (0.006-0. 008%) 的神经元转染. - 光显微镜

- 配制由119毫米氯化钠组成的生理盐水溶液, 2 毫米 CaCl 2 , 2.5 毫米氯化钾, 25 毫米 HEPES (pH 7.4), 30 毫米葡萄糖, 2 毫米氯化镁 2 , 0.01 毫米 6-氰基-7-nitroquinoxaline-23-酮 (CNQX) 和0.05 毫米 DL-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric 酸 (AP5)。采取片从培养基板和地方在一个成像室, 允许现场刺激, 使用润滑剂和密封剂, 以避免泄漏。避免让玻璃在片从盘子转移到腔室时, 立即加入750和 #181; 生理盐水溶液.

注: CNQX 和 AP5 被用来阻断突触后的活动, 有可能复发的活动。在倒置荧光显微镜上放置一个腔室之前, 使用清洁组织来确认腔室不泄漏。在记录过程中, 由于生理盐水和浸泡油的混合而导致焦点变化, 导致折射率的变化. - 刺激和记录

- 在倒置的 widefield 显微镜上的

- 图像, 带有金属卤化物灯的 60X (1.4 数字孔径) 油浸透镜。可视化 pHluorin 与过滤器集为 480 nm 的励磁峰值, 一个 490 nm 长的通行证镜子, 一个 500-550 nm 发射过滤器, 和一个手动翻转快门。捕获图像每 100 ms, 与 2 x 2 分, 使用电子倍增电荷耦合设备 (EMCCD) 相机.

注意: 应考虑几个特性, 以达到适当的条件, 以避免漂白, 包括图像捕获间隔, 和过滤器和分, 这是依赖于设备。在共焦成像的情况下, 应考虑激光功率和曝光时间, 以避免漂白。该设置是在记录至少3分钟没有刺激和记录进行了至少十年代没有刺激检查漂白. - 选择具有高密度 boutons 的区域, 以便于在每个实验中进行分析。通过其绿色荧光信号来识别转染细胞, 强调溥和 boutons 之间连续表达的圆形或椭圆形的表达模式.

- 利用1毫秒脉冲激发吞, 20 mA 动作电位 (AP) 由脉冲刺激器提供, 并通过刺激隔离单元中的铂电极传递。在刺激过程中和细胞恢复过程中的图像荧光活动.

注意: 在死细胞的情况下, 表达比活 boutons 强, 并且显示了一个参差不齐的样式在 boutons 之间.

- 图像, 带有金属卤化物灯的 60X (1.4 数字孔径) 油浸透镜。可视化 pHluorin 与过滤器集为 480 nm 的励磁峰值, 一个 490 nm 长的通行证镜子, 一个 500-550 nm 发射过滤器, 和一个手动翻转快门。捕获图像每 100 ms, 与 2 x 2 分, 使用电子倍增电荷耦合设备 (EMCCD) 相机.

- 配制由119毫米氯化钠组成的生理盐水溶液, 2 毫米 CaCl 2 , 2.5 毫米氯化钾, 25 毫米 HEPES (pH 7.4), 30 毫米葡萄糖, 2 毫米氯化镁 2 , 0.01 毫米 6-氰基-7-nitroquinoxaline-23-酮 (CNQX) 和0.05 毫米 DL-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric 酸 (AP5)。采取片从培养基板和地方在一个成像室, 允许现场刺激, 使用润滑剂和密封剂, 以避免泄漏。避免让玻璃在片从盘子转移到腔室时, 立即加入750和 #181; 生理盐水溶液.

- 图像分析

- 为了分析单个溥的荧光强度, 建立了一个 1.5 x 1.5 和 #181 的感兴趣区域; m 平方;溥的大小在大约1.5 和 #181; m. 在刺激之前使用痕迹检查漂白和减去作为背景.

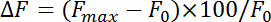

- 规范化荧光变化 (和 #916; f) 与等式:

其中 f 最大 和 f 0 是指刺激后的最大增加和基线荧光, 分别。测量吞率的衰变率在前4-10 秒后的最大点 pHluorin 荧光。获得时间常数 (和 #964;) 吞通过拟合 pHluorin 荧光衰变从峰值增加到基线的单指数函数.

2。电子显微镜

- 在室温下, 用1.5 毫升0.01% 无菌过滤的聚-d-赖氨酸溶液在每个井中为1小时, 然后用灭菌的水冲洗三次, 以制备多聚-d-赖氨酸涂层 6-好的板材。解剖, 培养和维持海马神经元的步骤 1.1.1, 1.1.2, 和1.1.3 分别.

- 准备一个高 K + 的刺激方案, 用 HRP 作为31.5 毫米氯化钠, 2 毫米 CaCl 2 , 90 毫米氯化钾, 25 毫米 HEPES (pH 7.4), 30 毫米葡萄糖, 2 毫米氯化镁 2 , 0.01 毫米 CNQX, 0.05 毫米 AP5, 5 毫克/毫升 HRP, 然后调整到 pH 7.4 与5米氢氧化钠.

- 在室温下使用 1.5 ml 高 K + 刺激方案刺激海马神经元培养 (称为 K + ), 并在九十年代对每个井加1.5 毫升。在休息条件 (简称 R), 适用于九十年代相同浓度的5毫克/毫升 HRP, 但与生理盐水溶液。对于恢复样本, 应用高 k + 刺激解决方案与 k + 样本, 然后快速清洗和替换生理盐水和孵化为10分钟

- 固定和着色

- 使用21.4 克/L na 甲在 pH 值7.4 处准备 0.1 M na 甲缓冲区。在室温下, 用4% 戊二醛在0.1 米甲缓冲中固定细胞, 至少1小时。洗涤三次与 0.1 M Na 甲缓冲为7分钟每个.

- 准备 Diaminobenzidine (民建联) 解决方案, 由0.5 毫克/毫升的民建联与 0.3% H 2 O 2 在 ddH 2 O, 和过滤器与0.22 和 #181; m 过滤器。应用1.5 毫升民建联解决方案为30分钟, 在37和 #176; c. 洗涤三次以 0.1 M Na 甲缓冲为 7 min 每个.

警告: 民建联是一种有毒和可疑的致癌物。请使用手套和实验室大衣.

注: 与民建联的标签, 是由于其氧化的 H 2 O 2 , 由 HRP 催化。小的增加在组分导致一个增加的信号在样品。增加 HRP 的浓度会加速催化剂的作用。足够大的浓度的 H 2 O 2 允许与 HRP 削弱的副作用, 抑制标记 32 的效果。在这项工作中, 这个标签系统的浓度是根据目前可用的研究选择 33 , 34 。 - 孵育1.5 毫升 1% OsO 4 在 0.1 M Na 甲缓冲区为1和 #176; C 作为后固定。洗涤三次与1.5 毫升 0.1 M Na 甲缓冲区为7分钟每.

注意: 由于 OsO 4 的毒性和反应性, 在许多情况下, 将样品放在化学罩的冰上比使用冰箱进行孵化更可取. - 制备0.1 米醋酸钠缓冲液, 13.61 克/升醋酸钠和11.43 毫升/升冰醋酸在 pH 值5.0。洗涤三次以1.5 毫升 0.1 M 乙酸酯缓冲在 ph 5.0 为7分钟每和孵育与1.5 毫升1% 铀乙酸酯在 0.1 m 醋酸盐缓冲在 ph 5.0 为 1 h 在4和 #176; c. 洗涤三次与1.5 毫升 0.1 m 醋酸盐缓冲7分钟每.

- 环氧嵌入

- 将神经元培养脱水为50%、70% 和90% 乙醇的单1.5 毫升洗涤, 在每一个7分钟, 然后3毫升1.5 的洗涤在油烟罩中每100% 分钟.

- 混合485毫升/升双酚 A-(epichlorhydrin) 环氧树脂, 160 毫升/升烯丁二酸酐 (DDSA), 340 毫升/升 Methyl-5-Norbornene-2,3-Dicarboxylic 酸酐 (NMA), 和15毫升/升 24, 6-三 (甲基) 苯酚 (DMP-30) 创建环氧树脂树脂.混合彻底, 然后储存在真空中, 以消除气泡.

注意: 这是至关重要的, 以消除气泡的树脂, 特别是那些小于肉眼可见, 因为它们可以导致在树脂切片期间的蛀牙. - 通过将乙醇中的50% 环氧树脂替换为乙醇中的30分钟, 然后在振动筛的室温下将70% 的环氧树脂用于乙醇中, 从而将其渗透到样品中.

- 用100% 环氧树脂开关环氧树脂溶液, 孵育10分钟, 在50和 #176; c. 在50和 #176 进行1小时孵化的两次新的100% 环氧树脂的交换; c. 加入新鲜的100% 环氧树脂, 并允许在50和 #176 硬化; c 过夜, 然后在60和 #176;C 超过36小时硬化.

- 从具有珠宝商和 #39 的多井板中卸下每个样品; 手锯。选择感兴趣的区域, 密集的细胞浓度, 使用倒置的光显微镜, 然后削减70至 80 nm 块的切片由切片。在切片卡盘中安装剪切区域并加载切片。将卡盘放置在切片中, 然后装上一把与该块表面平行的边缘的金刚石刀。将70至 80 nm 厚度的剖面直接收集到单个网格上.

- 通过重量将醋酸铀溶入水中1% 溶液, 并将柠檬酸铅分解为3% 溶液。Counterstain 1% 水铀醋酸盐浸泡15分钟, 然后3% 水柠檬酸铅5分钟, 以改善样品的对比度.

- EM 成像

- 使用透射电子显微镜检查剖面, 并在 10,000-20,000X 3 的主要放大倍数下记录 CCD 数字照相机的图像.

- 统计

- 执行 t 测试, 通过比较控制和实验样本之间的测量 (s.e.m.) 的平均值和标准误差来识别显著的差异.

结果

使用脂质载体法, SpH 表达了海马神经元, 允许识别 boutons (图 1a)。电刺激细胞诱导胞, 并相应增加荧光强度。荧光 (δ) 的增加是通过终止刺激 (图 1b) 停止的。随着吞的增加, 荧光量也随之缓慢下降。在 VAMP2-pHluorin 的情况下, VAMP2 扩散沿轴突从一个溥后刺激4。原始数据使用任意单位, 并被规范化到基线以获得衰变?...

讨论

这里我们展示了两种监测突触囊泡吞的方法。在第一种方法中, 我们监测 pHluorin 融合的突触泡蛋白在转染神经元和随后电刺激。其次, 我们使用的 EM 成像的 HRP 吸收诱导氯化钾。我们使用不同的刺激有两个原因。首先, 高钾的应用诱导了培养中所有神经元的去极化。这有助于 em 检查, 因为我们的 em 方法不能区分陶土和受激神经元。其次, 微的形态学变化更可靠地观察后, 强烈的刺激, 如高钾刺激, 而...

披露声明

作者没有什么可透露的。

致谢

我们感谢 Dr. 的 synaptophysin-pHluorin2x 建造, Dr. 提供 VAMP2-phluorin。我们感谢 Dr. 苏珊和弗吉尼亚克罗克的一电子显微镜设施的技术支持和帮助。这项工作得到了美国国家神经疾病研究所和脑卒中内部研究计划的支持, 并得到了 KRIBB 研究计划 (韩国生物医学科学家研究项目) 的资助, 韩国研究所大韩民国生物科学和生物工程。

材料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Lipofectamine LTX with Plus | Thermo Fisher | 15338-100 | Transfection of plasmid DNA including synaptophysin or VAMP2-pHluorin |

| neurobasal medium | Thermo Fisher | 21103-049 | Growth medium for neuron, Warm up to 37°C before use |

| B27 | Thermo Fisher | 17504-044 | Gradient for neuronal differentiation |

| Glutamax | Thermo Fisher | 35050-061 | Gradient for neuronal culture |

| Poly-D-Lysine coated coverslip | Neuvitro | GG-25-pdl | Substrate for neuronal growth and imaging of pHluorin |

| Trypsin XI from bovine pancrease | Sigma | T1005 | Neuronal culture-digest hippocampal tissues |

| Deoxyribonuclease I from bovine pancreas | Sigma | D5025 | Neuronal culture-inhibits viscous cell suspension |

| pulse stimulator | A-M systems | model 2100 | Apply electrical stimulation |

| Slotted bath with field stimulation | Warner Instruments | RC-21BRFS | Apply electrical stimulation |

| stimulus isolation unit | Warner Instruments | SIU102 | Apply electrical stimulation |

| lubricant | Dow corning | 111 | pHluorin imaging-seal with coverslip and imaging chamber, avoid leak from chamber |

| AP5 | Tocris | 3693 | Gradient for normal saline, selective NMDA receptor antagonist, inhibit postsynaptic activity which have potential for recurrent activity |

| CNQX | Tocris | 190 | Gradient for normal saline, competitive AMPA/kainate receptor antagonist, inhibit postsynaptic activity which have potential for recurrent activity |

| Illuminator | Nikon | C-HGFI | Metal halide light source for pHluorin |

| EMCCD camera | Andor | iXon3 | pHluorin imaging, detect pHluorin fluorescence intensity |

| Inverted microscopy | Nikon | Ti-E | Imaging for synaptophysin or VAMP2 pHluorin transfected cells |

| NIS-Elements AR | Nikon | NIS-Elements Advanced Research | Software for imaging acquisition and analysis |

| Igor Pro | WaveMetrics | Igor pro | Software for imaging analysis and data presentation |

| imaging chamber | Warner Instruments | RC21B | pHluorin imaging, apply field stimulation on living cells |

| poly-l-lysine | Sigma | P4832 | Electron microscopy, substrate for neuronal growth, apply on multiwell plate for 1 h at room temperature then wash with sterilized water 3 times |

| Horseradish peroxidase(HRP) | Sigma | P6782 | Electron microscopy, labeling of endocytosed synaptic vesicles by catalyzing DAB in presence hydrogen peroxide, final concentration is 5 mg/mL in normal saline, make fresh before use |

| Na cacodylate | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 12300 | Electron microscopy, buffer for fixatives and washing, final concentration is 0.1 N |

| 3,3′-Diaminobenzidine(DAB) | Sigma | D8001 | Electron microscopy, labeling of endocytosed synaptic vesicles, substrate for HRP, final concentration is 0.5 mg/mL in DDW and filtered, make fresh before use |

| Hydrogen peroxide solution | Sigma | H1009 | Electron microscopy, labeling of endocytosed synaptic vesicles by inducing HRP-DAB reaction, final concentration is 0.3% in DDW, make fresh before use |

| glutaraldehyde | Electron Microscopy Sciences | 16365 | Electron microscopy, fixatives, final concentration is 4% in Na-cacodylate buffer, make fresh before use, shake well before to use |

| TEM | JEOL | 200CX | Electron microscopy, imaging of endocytosed vesicles and ultrastructural changes |

| CCD digital camera | AMT | XR-100 | Electron microscopy, capturing images |

| Lead citrate | Leica microsystems | 16707235 | Electron microscopy, grid staining |

参考文献

- Sankaranarayanan, S., Ryan, T. A. Real-time measurements of vesicle-SNARE recycling in synapses of the central nervous system. Nature cell biol. 2 (4), 197-204 (2000).

- Sun, T., Wu, X. S., et al. The role of calcium/calmodulin-activated calcineurin in rapid and slow endocytosis at central synapses. J Neurosci. 30 (35), 11838-11847 (2010).

- Wu, X. -. S. S., Lee, S. H., et al. Actin Is Crucial for All Kinetically Distinguishable Forms of Endocytosis at Synapses. Neuron. 92 (5), 1020-1035 (2016).

- Granseth, B., Odermatt, B., Royle, S. J., Lagnado, L. Clathrin-mediated endocytosis is the dominant mechanism of vesicle retrieval at hippocampal synapses. Neuron. 51 (6), 773-786 (2006).

- Atluri, P. P., Ryan, T. A. The kinetics of synaptic vesicle reacidification at hippocampal nerve terminals. J Neurosci. 26 (8), 2313-2320 (2006).

- Royle, S. J., Granseth, B., Odermatt, B., Derevier, A., Lagnado, L. Imaging phluorin-based probes at hippocampal synapses. Methods Mol Biol. 457, 293-303 (2008).

- Moulder, K. L., Mennerick, S. Reluctant vesicles contribute to the total readily releasable pool in glutamatergic hippocampal neurons. J Neurosci. 25 (15), 3842-3850 (2005).

- Li, Z., Burrone, J., Tyler, W. J., Hartman, K. N., Albeanu, D. F., Murthy, V. N. Synaptic vesicle recycling studied in transgenic mice expressing synaptopHluorin. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 102 (17), 6131-6136 (2005).

- Morris, R. G. Elements of a neurobiological theory of hippocampal function: the role of synaptic plasticity, synaptic tagging and schemas. Eur J Neurosci. 23 (11), 2829-2846 (2006).

- Sankaranarayanan, S., Ryan, T. A. Calcium accelerates endocytosis of vSNAREs at hippocampal synapses. Nat Neurosci. 4 (2), 129-136 (2001).

- Balaji, J., Armbruster, M., Ryan, T. A. Calcium control of endocytic capacity at a CNS synapse. J Neurosci. 28 (26), 6742-6749 (2008).

- Ferguson, S. M., Brasnjo, G., et al. A selective activity-dependent requirement for dynamin 1 in synaptic vesicle endocytosis. Science. 316 (5824), 570-574 (2007).

- Baydyuk, M., Wu, X. S., He, L., Wu, L. G. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor inhibits calcium channel activation, exocytosis, and endocytosis at a central nerve terminal. J Neurosci. 35 (11), 4676-4682 (2015).

- Wu, X. S., Zhang, Z., Zhao, W. D., Wang, D., Luo, F., Wu, L. G. Calcineurin is universally involved in vesicle endocytosis at neuronal and nonneuronal secretory cells. Cell Rep. 7 (4), 982-988 (2014).

- Zhang, Z., Wang, D., et al. The SNARE proteins SNAP25 and synaptobrevin are involved in endocytosis at hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci. 33 (21), 9169-9175 (2013).

- Wu, L. -. G. G., Hamid, E., Shin, W., Chiang, H. -. C. C. Exocytosis and endocytosis: modes, functions, and coupling mechanisms. Annu Rev Physiol. 76 (1), 301-331 (2014).

- Daniele, F., Di Cairano, E. S., Moretti, S., Piccoli, G., Perego, C. TIRFM and pH-sensitive GFP-probes to evaluate neurotransmitter vesicle dynamics in SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells: cell imaging and data analysis. J Vis Exp. (95), e52267 (2015).

- Shaner, N. C., Lin, M. Z., et al. Improving the photostability of bright monomeric orange and red fluorescent proteins. Nat Methods. 5 (6), 545-551 (2008).

- Li, Y., Tsien, R. W. pHTomato, a red, genetically encoded indicator that enables multiplex interrogation of synaptic activity. Nat Neurosci. 15 (7), 1047-1053 (2012).

- Leitz, J., Kavalali, E. T. Fast retrieval and autonomous regulation of single spontaneously recycling synaptic vesicles. Elife. 3, e03658 (2014).

- Bisht, K., El Hajj, H., Savage, J. C., Sánchez, M. G., Tremblay, M. -. &. #. 2. 0. 0. ;. Correlative Light and Electron Microscopy to Study Microglial Interactions with β-Amyloid Plaques. J Vis Exp. (112), e54060 (2016).

- Schikorski, T. Monitoring Synaptic Vesicle Protein Sorting with Enhanced Horseradish Peroxidase in the Electron Microscope. High-Resolution Imaging of Cellular Proteins: Methods and Protocols. , 327-341 (2016).

- Kononenko, N. L., Puchkov, D., et al. Clathrin/AP-2 mediate synaptic vesicle reformation from endosome-like vacuoles but are not essential for membrane retrieval at central synapses. Neuron. 82 (5), 981-988 (2014).

- Wu, Y., O'Toole, E. T., et al. A dynamin 1-, dynamin 3- and clathrin-independent pathway of synaptic vesicle recycling mediated by bulk endocytosis. eLife. 2014 (3), e01621 (2014).

- Heuser, J. E., Reese, T. S. Evidence for recycling of synaptic vesicle membrane during transmitter release at the frog neuromuscular junction. J Cell Biol. 57 (2), 315-344 (1973).

- Ceccarelli, B., Hurlbut, W. P., Mauro, A. Turnover of transmitter and synaptic vesicles at the frog neuromuscular junction. J Cell Biol. 57 (2), 499-524 (1973).

- Watanabe, S., Rost, B. R., et al. Ultrafast endocytosis at mouse hippocampal synapses. Nature. 504 (7479), 242-247 (2013).

- Watanabe, S., Trimbuch, T., et al. Clathrin regenerates synaptic vesicles from endosomes. Nature. 515 (7526), 228-233 (2014).

- Sankaranarayanan, S., Atluri, P. P., Ryan, T. A. Actin has a molecular scaffolding, not propulsive, role in presynaptic function. Nat Neurosci. 6 (2), 127-135 (2003).

- Zhu, Y., Xu, J., Heinemann, S. F. Two pathways of synaptic vesicle retrieval revealed by single-vesicle imaging. Neuron. 61 (3), 397-411 (2009).

- Miesenbock, G., De Angelis, D. A., Rothman, J. E. Visualizing secretion and synaptic transmission with pH-sensitive green fluorescent proteins. Nature. 394 (6689), 192-195 (1998).

- Arnao, M. B. B., Acosta, M., del Rio, J. A. A., García-Cánovas, F. Inactivation of peroxidase by hydrogen peroxide and its protection by a reductant agent. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1038 (1), 85-89 (1990).

- Deák, F., Schoch, S., et al. Synaptobrevin is essential for fast synaptic-vesicle endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 6 (11), 1102-1108 (2004).

- Clayton, E. L., Evans, G. J. O., Cousin, M. A. Bulk synaptic vesicle endocytosis is rapidly triggered during strong stimulation. J Neurosci. 28 (26), 6627-6632 (2008).

- Kavalali, E. T., Jorgensen, E. M. Visualizing presynaptic function. Nat Neurosci. 17 (1), 10-16 (2014).

- Wienisch, M., Klingauf, J. Vesicular proteins exocytosed and subsequently retrieved by compensatory endocytosis are nonidentical. Nat Neurosci. 9 (8), 1019-1027 (2006).

- Fernández-Alfonso, T., Kwan, R., Ryan, T. A. Synaptic vesicles interchange their membrane proteins with a large surface reservoir during recycling. Neuron. 51 (2), 179-186 (2006).

- Gimber, N., Tadeus, G., Maritzen, T., Schmoranzer, J., Haucke, V. Diffusional spread and confinement of newly exocytosed synaptic vesicle proteins. Nat Commun. 6, 8392 (2015).

- Nicholson-Fish, J. C., Smillie, K. J., Cousin, M. A. Monitoring activity-dependent bulk endocytosis with the genetically-encoded reporter VAMP4-pHluorin. J Neurosci Methods. 266, 1-10 (2016).

- Burrone, J., Li, Z., Murthy, V. N. Studying vesicle cycling in presynaptic terminals using the genetically encoded probe synaptopHluorin. Nat Protoc. 1 (6), 2970-2978 (2006).

- Wisse, E., Braet, F., et al. Fixation methods for electron microscopy of human and other liver. World journal of gastroenterology. 16 (23), 2851-2866 (2010).

- Magidson, V., Khodjakov, A. Circumventing Photodamage in Live-Cell Microscopy. Methods in Cell Biology. 114, 545-560 (2013).

- Søndergaard, C. R., Garrett, A. E., et al. Structural artifacts in protein-ligand X-ray structures: implications for the development of docking scoring functions. J Med Chem. 52 (18), 5673-5684 (2009).

转载和许可

请求许可使用此 JoVE 文章的文本或图形

请求许可This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

版权所属 © 2025 MyJoVE 公司版权所有,本公司不涉及任何医疗业务和医疗服务。