このコンテンツを視聴するには、JoVE 購読が必要です。 サインイン又は無料トライアルを申し込む。

Method Article

ネッタイシマカ蚊ボルバキアに感染維持

要約

ボルバキアに感染しているネッタイシマカ蚊はアルボ ウイルスの伝達を抑制する自然集団にリリースされています。我々 は研究所適応と選択範囲を最小限に抑えるための対策を講じて実験およびフィールド ・ リリース、ボルバキア感染症研究室と後部Ae。 ネッタイシマカに方法を説明します。

要約

ボルバキア感染ネッタイシマカ蚊はデング熱、チクングニア、ジカなどアルボ ウイルスの広がりを制御するためのプログラムで利用されています。ボルバキア-互換性のない交配による人口サイズを減らすか、またはウイルスの伝播に難治性蚊個体群に変換するフィールドに感染した蚊を解放ことができます。成功するためにこれらの戦略は、実験室からフィールドに蚊がネイティブ蚊と競争力のある必要があります。ただし、実験室で蚊を維持、近親交配や遺伝的浮動フィールドに自分の体力を減らすことができるし、実験の結果を混同するかもしれない研究所適応誤る。フィールドの配置のための別のボルバキア感染症の適合性をテストするため複数世代にわたって管理されたラボ環境で蚊を維持するために必要です。我々 は両方のボルバキアに適している所にAe。 ネッタイシマカ蚊を維持するための単純なプロトコルを記述する-感染し、野生型の蚊。メソッド研究所適応を最小限にし、実験フィールド蚊との関連性を高めるためアウトブ リードを実装します。さらに、植民地は、オープン フィールドのリリースのための自分の体力を最大化する最適な条件の下で維持されます。

概要

ネッタイシマカ蚊はデング熱、ジカ、チクングニア1を含む世界で最も重要なアルボ ウイルスの一部を送信するために責任があります。これらのウイルスは、熱帯地方でAe。 ネッタイシマカの広範な分布は2,3、4を展開し続けている地球規模の健康にさらなる脅威になっています。女性Ae。 ネッタイシマカ優先的に人間の血液5フィードし、従って人間、特に人口が最も密な都会の近くに住んでいる傾向にあります。この人間と密接な関係を彼らはまたタイヤやポット、溝、水タンク6,7を含む人工生息地で繁殖を適応しています。ネッタイシマカ Ae。は、どこ彼らはヤブカ属8、いくつかの他の種とは異なり、フィールドから直接収集される後要件を特別なことがなく維持することができます研究室環境にも容易に適応します。 9,10。メンテナンスの容易さは幅広い分野の研究所で広く研究それらを見ている、送信可能性があります最終的に病気蚊を制御することを目指しています。

伝統的に、arboviral コントロールは、蚊の個体数を減らすために殺虫剤の使用に大きく依存しています。ただし、組み換え蚊の飼育し、自然集団にそれから解放されるどこのアプローチに関心が高まっています。遺伝子11,12,13, 生物学的14,15、照射まで16、化学治療17,18, リリースされた蚊を変更することがあります。または結合テクニック19蚊の個体数を抑制または arboviral 伝送20に難治性蚊でそれらを置換します。

ボルバキアは現在.アルボ ウイルスの生物防除剤として使用されている細菌です。いくつかの系統のボルバキア最近Ae。 ネッタイシマカ胚マイクロインジェクション21,22,23,24を用いて実験導入されました。これらの系統はアルボ ウイルスを発信し、その伝送潜在的な23,25,26,27,28 を減少、蚊で複製の容量を減らす.しかし、感染した男性は、感染していない女性22と交尾するとき特定の菌株が不妊を誘発するボルバキア感染症は母からの子孫に送信されます。ボルバキア-自然な蚊の個体数、最近他ヤブカ属種15,29で実証を抑える大量に感染した男性を解放できます。ただし、ボルバキアはまたAe。 ネッタイシマカにおける arboviral 伝送を阻害する、ので、蚊は貧しいベクトル ネイティブ集団に置き換えるにも解放します。Ae。 ネッタイシマカボルバキアに感染は、この後者のアプローチ14,30,31を使用していくつかの国のフィールドに今リリースされています。

ボルバキア-arboviral コントロール ベースのアプローチがボルバキア蚊と環境間の相互作用の正しい理解に依存します。ボルバキアは昆虫の広い範囲で自然発生して蚊に導入された系統の効果32に多様であります。新しいボルバキア感染型がAe。 ネッタイシマカ24に導入し、各蚊フィットネス、複製および条件の範囲の下で arboviral の干渉に及ぼすひずみの特性評価に必要です。実験室での厳密な実験は、ボルバキア系統分野で成功するための潜在性を評価するため必要です。

オープン フィールド リリースAe。 ネッタイシマカのボルバキア感染症はしばしば数千から数万するリリース ゾーンごとの蚊の飼育各週14,30,31を要求できます。初期リリースの成功は、多産33と交尾成功34,35最大限に大型の蚊を解放することによって改善できます。蚊は、動作とフィールド性能36,37に影響を与えることができる生理学の変更を引き起こす可能性があります。 ただし長期研究所子育てにおいて必要となる条件に合わせる必要があります。 38。

基本的な機器を使用して実験室でAe。 ネッタイシマカを飼育用簡易プロトコルについて述べる。このプロトコルに適して両方の野生型とボルバキアの後者では、いくつかの系統のボルバキア蚊生活史形質39,に対する相当な効果を持っていると、特に注意が必要ことができます蚊を感染40飼育状況を過密とベクトル能力およびフィットネス実験に不可欠です、蚊がフィールド リリース41 健康確保されます一貫性のあるサイズの蚊を生成する食糧のための競争を避ける。.また選択的な圧力を減らすことによって研究所適応と近親交配を最小限に抑えるための予防策をとるし、大きなランダム プールからサンプリングは次の世代を確保すること。ただし、研究室環境は明らかに異なる圃場条件、リラックスした条件の下での長期的な保守は、フィールド37,42,43 にリリース時に蚊のフィットネスを減らすことができます。.我々 はこのため、フィールド収集の男性で、定期的に検査ラインから実験的比較のため遺伝的に類似しているし、ターゲット フィールド人口39に適応しており、植民地の女性を越えます。メソッドは、特別な機器を必要としないし、フィールド リリース週個人の何千もの数十奥にスケール アップすることができます。プロトコルはまた蚊内および世代間のフィットネス、自然集団の設立宛ての昆虫のための重要な考慮事項を優先します。プロトコルは、特に蚊やフィールドに relatability の一貫した品質が重要な実験的比較のためのAe。 ネッタイシマカメンテナンスが必要なほとんどの所に適しています。

プロトコル

メルボルン人間倫理委員会の大学によって承認されたヒトに蚊の吸血 (承認 #: 0723847)。提供すべてのボランティアは、書面による同意を通知しました。

1. 仔魚飼育

注: 蚊は、26 ± 0.5 ° C、50-70% 相対湿度、このコロニーの管理用プロトコルの 12:12 h (明暗): 日長で開催されます。これらの条件は、 Ae。 ネッタイシマカ生存の開発44,45,46平均気候条件でケアンズ、オーストラリアと最適な熱設計レンジ内に似ています。高温ボルバキア感染蚊の植民地の損失につながるし、回避47をする必要があります。近親交配; を最小限に抑えるため人口あたりの少なくとも 500 の個人を維持します。小さいサイズの植民地を維持するフィットネス結果 [ロスら未発表] を持つことができます。[これらの条件と仮定して十分な栄養、平均世代時間は 28 日 (表 1参照) です。

- 魚料理の ~ 300 mg 基板上 3 L の水 (逆浸透膜水または高齢者の水道水、24 h 使用前のトレイで水道水を残すことによって生成された) を含んでいる (図 1 a) 皿に卵が水没 (押しつぶさ 1 タブレット、材料表を参照してください)、孵化48を誘導するためにアクティブな乾燥酵母のいくつかの穀物。

- 孵化後 1 日約 500 幼虫を 4 リットルの水 (図 1 b) を含んでいる皿に転送、クリッカーのカウンターを使用してカウントするガラス ピペットを使用します。各トレイに 2 つの砕いた魚食品錠剤を追加します。必要な場合、飼育幼虫 (図 1 a)、異なるサイズのコンテナーを使用してが、混雑を避けるため 0.5 幼虫/mL 以下の幼虫の密度を保ちます。

- 十分な食べ物がある幼虫を毎日トレイを確認します。約 2 つの食品の錠剤カセット 2 日毎に追加します。食品広告の自由を提供するが、0.5 mg/幼虫/日は開発は同期し、本体サイズを確保するためこの期間中に利用可能な一貫性のあるは、実験の結果が混同されることがありますそれ以外の場合 (代表の結果を参照してください)。

- 幼虫の過食を避けるために世話をする、特に小型飼育容器少ない表面積および体積の水します。水に見える曇りまたは有意な幼虫の死亡率がある場合は、新鮮な水と交換します。死亡率は幼虫が最適に供給される場合は無視する必要があります。

2. 羽化

注: は、よく供給される場合、孵化後 5 日目から蛹になる幼虫が開始され、大半が孵化後 7 日で蛹。大人は 26 ° C に最適維持した場合蛹化後約 2 日を新たな開始されます (代表の結果を参照してください)。十分な食べ物が23,,3949を提供されるとき、幼虫の発育は通常ボルバキア感染によって影響を受ける。

- 孵化後 7 日間は細かいメッシュを通してトレイの内容全体を注ぐ (細孔サイズ 0.4 mm)。Ovicups で後で使用できるフィルター処理された幼虫水を保つ (「血の摂食と産卵」セクションを参照).メッシュを反転し、蛹を転送するための水の 200 mL のプラスチック製の容器にそれをつけます。任意の幼虫が残っている場合は、追加の食糧を提供します。

- 10% ショ糖液 (図 1 階) の 2 つのカップと乾燥 (図 1E) を防ぐために湿ったコットン ウールの 2 つのカップを提供することで羽化ケージ (図 1) を準備します。

- 蛹は、セックスでソートする必要はありません、ケージに蛹の蓋付きの容器を配置し、蓋を少しケージに出現する大人を許可するように半開き。また、逆漏斗を溺死を最小限に抑えるためコンテナーにかぶせます。すべての大人が遅い開発者に対して選択を防ぐためにケージからコンテナーを削除する前に浮上しているを確認します。

3. 蛹アウトブ リードを雌雄鑑別

- 蛹はセックス (例えば、アウトブ リードの) でソートする場合、トレイの幼虫から蛹のピペット、男女 (図 2) に分割プラスチック容器 (図 1 a) 200 mL の水ですべての 24 h 各性の必要な数まで達しています。容器に蓋を配置して閉じておきます。

- 大人は、容器に出てくるケージ (図 2) に解放する前に性別を確認します。性欲を刺激しない正しく出現の 24 h 内吸引で性的に成熟に達する前に大人を削除します。男女が確認した後は、すべての 24 h の檻に大人をリリースします。

-

ボルバキアを取得する-自然な人口に類似した遺伝的背景の感染したコロニー outcrossボルバキアを追加することによって-の人件によって収集された卵から感染していない男性のケージに植民地研究室から女性を感染フィールド39、人口あたりの 500 の個人の所定の密度を維持します。

- 少なくとも 87.5% フィールド人口39遺伝的に類似のコロニーを生成する少なくとも 3 つの連続した世代の交雑を繰り返します。重要: この段階では、男女が正しいことことを確認 (手順 3.1 参照)。

- 女性Ae。 ネッタイシマカは、さらに受精交尾50時間以内に通常耐火物。コロニーをアウトブ リードとは、すべての男性に、平等な機会を提供する 2 日間別のケージの中で成熟し、オスのケージにメスを吸引の女性と男性を許可します。

4. 吸血と産卵

-

最後の女性は成熟する十分な時間を許可するように吸血の前に出現した後少なくとも 3 日間待ちます。血液は、過剰死亡率、特に悪影響を及ぼす長寿22,24,49ボルバキア感染症と蚊を防ぐために出現の 2 週間以内、女性をフィードしました。砂糖カップ供給率を改善するために供給する前に日を削除します。

- フィードにメスの蚊を許可するようにケージに前腕を挿入するボランティアを頼みなさい。ほとんどの女性が 5 分以内で腹いっぱいフィードしますが、遅いフィーダーに対して選択範囲を減らすために、15 分間またはすべての女性は充血目に見えて; までケージで前腕を残す刺されてから手を保護するためにラテックス手袋はオプションですが推奨されます。

- 吸血後、2 日間は、卵を産むための女性のためケージに幼虫飼育水を含むとサンドペーパー (図 1) (またはろ紙 (図 1 H)) のストリップと並ぶ 2 つのプラスチック カップを配置します。部分的にそれを湿った保つ水サンドペーパー ストリップが水没します。その他女性が産卵カップ外卵を産むを防ぐために水の源を削除します。

注: は、カップで水道水を使用することがありますが、仔魚飼育水が産卵51,52を奨励し、女性はより同期的に彼らの卵を産みます。

5. 卵のコレクションとコンディショニング

- 女性はサンドペーパー、水行のすぐ上に卵を産む収集し、ないより多くの卵を置いたまで紙やすりのストリップを毎日交換します。産卵したが 1 週間続けることがありますに注意してください。

- 軽く 30 のペーパー タオルの上それらをしみが付くことによって部分的に乾燥サンドペーパー ストリップ s、卵が外れないように世話します。乾燥したペーパー タオルのシートでストリップをラップし、密閉式のビニール袋 (図 1I) に配置します。

- 解剖顕微鏡 (図 3) の下で卵の状態を確認します。場合はサンドペーパーのストリップが余りにぬれて、水 (図 3 b)、水没する前に卵がありますが、卵も厳しく、乾燥した場合 (図 3) 崩壊するかもしれない。

- 卵は 3 日後コレクションを超えていつでも孵化することができます。個人の大きなランダム プールから次世代をサンプリングするように水の同じコンテナーにすべての日にわたって収集、各コロニーからのすべての卵を孵化します。

- 長期保存用は、20 ° c. のまわりで、(> 80%) 高湿度で密封された容器で卵をしてください。これらの条件の下で高いハッチ率53,54を維持しながら数ヶ月間卵ボルバキアなくを格納できます。

- いくつかのボルバキア感染年齢49,55卵の生存率を大幅に削減とボルバキアから卵を孵化-線関連の余分な死亡率を防ぐためにコレクションの 1 週間以内に感染しています。系統。血は 1 週間後に再度女性をフィード以上の卵が必要な場合。

| 日 | ステップ | ||

| 0 | ハッチ卵 | ||

| 1 | トレイに数幼虫 | ||

| 7 | コロニーのケージに幼虫や蛹を転送します。 | ||

| 17 | 血を養う雌成虫 | ||

| 21 | 卵の収集を開始します。 | ||

| 25 | 卵を収集完了します。 | ||

| 28 | ハッチ卵 | ||

表 1:26 でAe ネッタイシマカコロニー メンテナンス スケジュールの概要 ° c 。女性吸血、卵の孵化のタイミングは柔軟性が高く、しかし、ボルバキア、死亡率を最小限に抑えるため感染蚊のために特に、これらの段階での長い期間を避ける必要があります。このスケジュールは以下の幼虫が最適に供給されることは、高速または開発またはすべてのライフ ステージで成熟するが遅い蚊に対する選択を最小限にします。

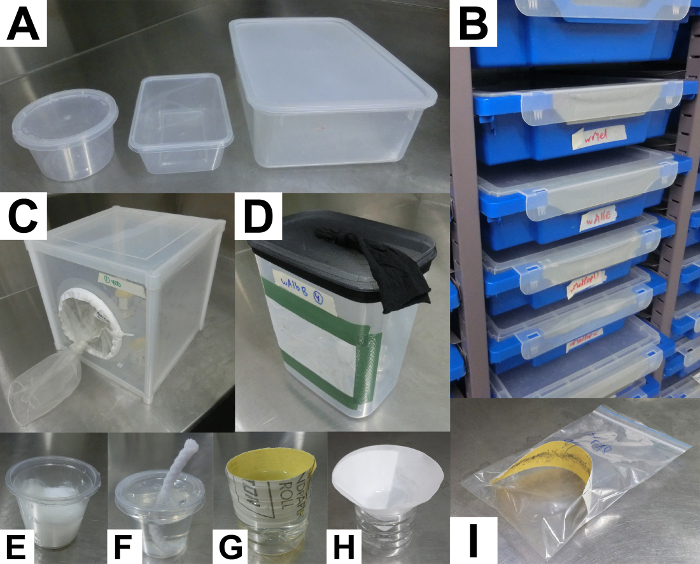

図 1: 機器Ae ネッタイシマカ研究室での飼育に使用します。 。(A) プラスチック容器、卵を孵化または 500 のボリュームで幼虫を飼育 (左から右へ) 750 と 5,000 mL。(B) トレイ 4 L の水に通常 500 幼虫管理密度で幼虫の飼育に使用します。(C) 19.7 L や 3 L (D) ケージ住宅大人に使われます。25 大人の密度またはリットル以下は十分なスペースを提供するために維持されるべき。(E) 35 mL カップに湿った脱脂綿大人への水の源として提供します。砂糖の原料としてコードまたは歯科芯を通じて提供されるショ糖 (F) 35 mL カップ。(G-H)カップ幼虫飼育水で満たされた、サンドペーパーまたはフィルター ペーパーの産卵基質が並ぶ (G H、それぞれ)。(私) Zip ロック袋サンドペーパー ストリップまたはろ紙のストレージに使用されます。サンドペーパーに黒い斑点が、蚊の卵です。この図の拡大版を表示するのにはここをクリックしてください。

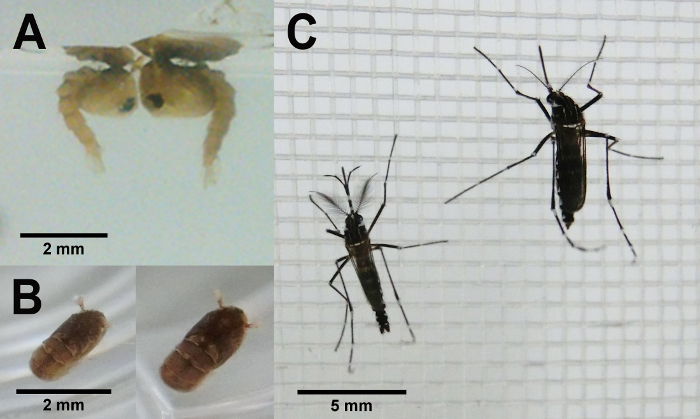

図 2: 横 (A) と背 (B) ビューの蛹と (C) の性の二形性を示す大人ネッタイシマカ Ae 。 。男性は、左右の各パネルの右上の女性に配置されます。オスとメスの蛹がサイズによって区別される最適供給されるとき女性男性 (A) よりも大きく、比較的球根の頭胸部平坦な側面 (B) のある男性と比較しています。成人男性は、環状アンテナと長い palps によって主にすべての飼育条件下での女性と簡単に区別されます。この図の拡大版を表示するのにはここをクリックしてください。

図 3。異なる条件下で 4 日間の古いAe。 ネッタイシマカの卵。(A) そのまま卵サンドペーパー ストリップ、可視可能な湿気ではなく (> 80%) 高湿度を維持します。正しく維持される場合ハッチ率は野生型Ae。 ネッタイシマカの 90% を超えるはずです。(早熟な孵化) 水に浸漬されている前にハッチ (B) 卵は、戸建の卵の帽子と目に見える幼虫によって区別されます。これはサンドペーパー ストリップだったあまりにも湿った保たれることを示します。厳しく乾燥 (C) 卵に崩壊するかもしれないと凹面外見で明確に表示されます。サンドペーパーは堅くなる場合は、卵が乾燥しすぎてかもしれないことをこれを示します。この図の拡大版を表示するのにはここをクリックしてください。

結果

図 4は、 Ae。 ネッタイシマカ幼虫の発育に最適な栄養の影響を示しています。ときコンテナー幼虫 1 日あたりの食品の 0.25 mg または以下の両方の男性と女性、開発時間が増加は容器のより少ない同期提供 0.5 mg 食品の。幼虫の発育期間を通して十分な食糧を指定しない場合このメンテナンス スケジュールに悪影響があります。遅い開発個?...

ディスカッション

ボルバキアのメンテナンスはここで説明したプロトコルに従う-感染したAe。 ネッタイシマカするように一貫した品質の健康的な蚊実験に対して生成されますフィールド リリースを開きます。(参照57を参照) 蚊の大量の生産を優先する他のプロトコルとは対照的メソッド、フィットネス、リラックスの飼育条件を実装することによって、全体の世代の両方を最大...

開示事項

著者は、彼らは競合する金銭的な利益があることを宣言します。

謝辞

我々 は、恒林 Yeap、クリス ペイトン、Petrina ジョンソンと我々 の植民地のメンテナンス方法の開発への貢献のクレア ・ ドイグ、原稿を改善するを助けた彼らの提案の 3 つの匿名レビューを認めます。私たちの研究は国民の健康からアーッにプログラム助成と交わりによってサポートされ、Wellcome の信頼からの医学研究評議会と翻訳を与えます。PAR は、オーストラリア政府研究研修プログラム奨学の受信者です。

資料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Wild type Aedes aegypti | Collected from field locations in Queensland, Australia, see Yeap and others39 for details | ||

| w Mel-infected Aedes aegypti | Provided by Monash University. Refer to Walker and others23 for information on the strain | ||

| w AlbB-infected Aedes aegypti | Provided by Monash University. Refer to Xi and others21 for information on the strain | ||

| w MelPop-infected Aedes aegypti | Provided by Monash University. Refer to McMeniman and others22 for information on the strain | ||

| Instant dried yeast | Lowan | Stimulates egg hatching. Found in general grocery stores. Other brands may be used | |

| 5 L plastic tub | Quadrant | Q110950 | Used for hatching and rearing larvae. Other products may be used |

| Fish Food (Tetramin Tropical Tablets) | Tetra | 16152 | Provided to larvae as a source of food. Web address: https://www.amazon.com/Tetra-16152-TetraMin-Tropical-10-93-Ounce/dp/B00025Z6SE |

| Plastic containers | Used for rearing larvae. Any plastic container above 500 mL should be suitable | ||

| Glass pipette | Used for transferring larvae and pupae between containers. Web address: https://www.aliexpress.com/item/10Pcs-Durable-Long-Glass-Experiment-Medical-Pipette-Dropper-Transfer-Pipette-Lab-Supplies-With-Red-Rubber-Cap/32704471109.html?spm=2114.40010308.4.2.py4Kez | ||

| Clicker counter | RS Pro | 710-5212 | Used to assist in the counting of larvae, pupae and eggs. Web address: http://au.rs-online.com/web/p/products/7105212/?grossPrice=Y |

| Rearing trays | Gratnells | Used for rearing larvae. Web address: http://www.gratnells.com | |

| Nylon mesh | Used to transfer larvae and pupae to containers of fresh water. Other brands may be used. Web address: https://www.spotlightstores.com/fabrics-yarn/specialty-apparel-fabrics/nettings-tulles/nylon-netting/p/BP80046941001-white | ||

| Cages | BugDorm | DP1000 | Houses adult mosquitoes. Alternative products may be used. Web address: http://bugdorm.megaview.com.tw/bugdorm-1-insect-rearing-cage-30x30x30-cm-pack-of-one-p-29.html |

| 35 mL plastic cup | Huhtamaki | AA272225 | Used to provide water or sucrose to adult mosquitoes. Other brands may be used |

| 35 mL plastic cup lid | Huhtamaki | GB030005 | Used to provide sucrose to adult mosquitoes. Other brands may be used |

| Cotton wool | Cutisoft | 71841-13 | Moist cotton wool is provided as a source of water to adults. Other brands may be used |

| White Sugar | Provided as a source of sugar to adult mosquitoes. Found in general grocery stores | ||

| Rope | M Recht Accessories | C323C/W | Used to provide sucrose solution to adults. Other brands may be used. Web address: https://mrecht.com.au/haberdashery/braids-cords-and-tapes/cords/plaited-cord/cotton/ |

| Plastic cup (large) | Used as an oviposition container. Any plastic cup that holds 100 mL of water should be suitable | ||

| Sandpaper | Norton Master Painters | CE015962 | Provided as an oviposition substrate. Alternative products may be used, but we use this brand because it is relatively odorless. Lighter colors are used for contrast with eggs. Web address: https://www.bolt.com.au/115mm-36m-master-painters-bulk-roll-p80-medium-p-9396.html |

| Filter paper | Whatman | 1001-150 | Used as an alternative oviposition substrate. Other brands may be used |

| Latex gloves | SemperGuard | Z560979 | Prevents mosquito bites on hands when blood feeding. Other brands may be used. Web address: http://www.sempermed.com/en/products/detail/semperguardR_latex_puderfrei_innercoated/ |

参考文献

- Mayer, S. V., Tesh, R. B., Vasilakis, N. The emergence of arthropod-borne viral diseases: A global prospective on dengue, chikungunya and zika fevers. Acta Trop. 166, 155-163 (2017).

- Campbell, L. P., et al. Climate change influences on global distributions of dengue and chikungunya virus vectors. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 370 (1665), (2015).

- Kraemer, M. U., et al. The global distribution of the arbovirus vectors Aedes aegypti and Ae. albopictus. eLife. 4, (2015).

- Carvalho, B. M., Rangel, E. F., Vale, M. M. Evaluation of the impacts of climate change on disease vectors through ecological niche modelling. Bull Entomol Res. , 1-12 (2016).

- Scott, T. W., et al. Longitudinal studies of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in Thailand and Puerto Rico: population dynamics. J Med Ent. 37 (1), 77-88 (2000).

- Cheong, W. Preferred Aedes aegypti larval habitats in urban areas. Bull World Health Organ. 36 (4), 586-589 (1967).

- Barker-Hudson, P., Jones, R., Kay, B. H. Categorization of domestic breeding habitats of Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) in Northern Queensland, Australia. J Med Ent. 25 (3), 178-182 (1988).

- Watson, T. M., Marshall, K., Kay, B. H. Colonization and laboratory biology of Aedes notoscriptus from Brisbane, Australia. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 16 (2), 138-142 (2000).

- Williges, E., et al. Laboratory colonization of Aedes japonicus japonicus. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 24 (4), 591-593 (2008).

- Munstermann, L. E. . The Molecular Biology of Insect Disease Vectors. , 13-20 (1997).

- McDonald, P., Hausermann, W., Lorimer, N. Sterility introduced by release of genetically altered males to a domestic population of Aedes aegypti at the Kenya coast. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 26 (3), 553-561 (1977).

- Rai, K., Grover, K., Suguna, S. Genetic manipulation of Aedes aegypti: incorporation and maintenance of a genetic marker and a chromosomal translocation in natural populations. Bull World Health Organ. 48 (1), 49-56 (1973).

- Harris, A. F., et al. Field performance of engineered male mosquitoes. Nature Biotechnol. 29 (11), 1034-1037 (2011).

- Hoffmann, A. A., et al. Successful establishment of Wolbachia in Aedes populations to suppress dengue transmission. Nature. 476 (7361), 454-457 (2011).

- O'Connor, L., et al. Open release of male mosquitoes infected with a Wolbachia biopesticide: field performance and infection containment. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 6 (11), e1797 (2012).

- Morlan, H. B. Field tests with sexually sterile males for control of Aedes aegypti. Mosquito news. 22 (3), 295-300 (1962).

- Grover, K. K., et al. Field experiments on the competitiveness of males carrying genetic control systems for Aedes aegypti. Entomol Exp Appl. 20 (1), 8-18 (1976).

- Seawright, J., Kaiser, P., Dame, D. Mating competitiveness of chemosterilized hybrid males of Aedes aegypti (L.) in field tests. Mosq News. 37 (4), 615-619 (1977).

- Zhang, D., Lees, R. S., Xi, Z., Gilles, J. R., Bourtzis, K. Combining the sterile insect technique with Wolbachia-based approaches: II- a safer approach to Aedes albopictus population suppression programmes, designed to minimize the consequences of inadvertent female release. PloS One. 10 (8), e0135194 (2015).

- McGraw, E. A., O'Neill, S. L. Beyond insecticides: new thinking on an ancient problem. Nature Rev Microbiol. 11 (3), 181-193 (2013).

- Xi, Z., Khoo, C. C., Dobson, S. L. Wolbachia establishment and invasion in an Aedes aegypti laboratory population. Science. 310 (5746), 326-328 (2005).

- McMeniman, C. J., et al. Stable introduction of a life-shortening Wolbachia infection into the mosquito Aedes aegypti. Science. 323 (5910), 141-144 (2009).

- Walker, T., et al. The wMel Wolbachia strain blocks dengue and invades caged Aedes aegypti populations. Nature. 476 (7361), 450-453 (2011).

- Joubert, D. A., et al. Establishment of a Wolbachia superinfection in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes as a ppotential approach for future resistance management. PLoS Pathog. 12 (2), e1005434 (2016).

- Ferguson, N. M., et al. Modeling the impact on virus transmission of Wolbachia-mediated blocking of dengue virus infection of Aedes aegypti. Sci Transl Med. 7 (279), 279ra237 (2015).

- Aliota, M. T., Peinado, S. A., Velez, I. D., Osorio, J. E. The wMel strain of Wolbachia Reduces Transmission of Zika virus by Aedes aegypti. Sci Rep. 6, 28792 (2016).

- van den Hurk, A. F., et al. Impact of Wolbachia on infection with chikungunya and yellow fever viruses in the mosquito vector Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 6 (11), e1892 (2012).

- Moreira, L. A., et al. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell. 139 (7), 1268-1278 (2009).

- Mains, J. W., Brelsfoard, C. L., Rose, R. I., Dobson, S. L. Female Adult Aedes albopictus Suppression by Wolbachia-Infected Male Mosquitoes. Sci Rep. 6, 33846 (2016).

- Nguyen, T. H., et al. Field evaluation of the establishment potential of wmelpop Wolbachia in Australia and Vietnam for dengue control. Parasit Vectors. 8, 563 (2015).

- Garcia Gde, A., Dos Santos, L. M., Villela, D. A., Maciel-de-Freitas, R. Using Wolbachia releases to estimate Aedes aegypti (Diptera: Culicidae) population size and survival. PloS One. 11 (8), e0160196 (2016).

- Hoffmann, A. A., Ross, P. A., Rašić, G. Wolbachia strains for disease control: ecological and evolutionary considerations. Evol Appl. 8 (8), 751-768 (2015).

- Briegel, H. Metabolic relationship between female body size, reserves, and fecundity of Aedes aegypti. J Insect Physiol. 36 (3), 165-172 (1990).

- Ponlawat, A., Harrington, L. C. Factors associated with male mating success of the dengue vector mosquito, Aedes aegypti. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 80 (3), 395-400 (2009).

- Segoli, M., Hoffmann, A. A., Lloyd, J., Omodei, G. J., Ritchie, S. A. The effect of virus-blocking Wolbachia on male competitiveness of the dengue vector mosquito, Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 8 (12), e3294 (2014).

- Imam, H., Zarnigar, G., Sofi, A., Seikh, The basic rules and methods of mosquito rearing (Aedes aegypti). Trop Parasitol. 4 (1), 53-55 (2014).

- Spitzen, J., Takken, W. Malaria mosquito rearing-maintaining quality and quantity of laboratory-reared insects. Proc Neth Entomol Soc Meet. 16, 95-100 (2005).

- Lorenz, L., Beaty, B. J., Aitken, T. H. G., Wallis, G. P., Tabachnick, W. J. The effect of colonization upon Aedes aegypti susceptibility to oral infection with Yellow Fever virus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 33 (4), 690-694 (1984).

- Yeap, H. L., et al. Dynamics of the "popcorn" Wolbachia infection in outbred Aedes aegypti informs prospects for mosquito vector control. Genetics. 187 (2), 583-595 (2011).

- Turley, A. P., Moreira, L. A., O'Neill, S. L., McGraw, E. A. Wolbachia infection reduces blood-feeding success in the dengue fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 3 (9), e516 (2009).

- Yeap, H. L., Endersby, N. M., Johnson, P. H., Ritchie, S. A., Hoffmann, A. A. Body size and wing shape measurements as quality indicators of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes destined for field release. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 89 (1), 78-92 (2013).

- Leftwich, P. T., Bolton, M., Chapman, T. Evolutionary biology and genetic techniques for insect control. Evol Appl. 9 (16), 212-230 (2016).

- Calkins, C., Parker, A. . Sterile Insect Technique. , 269-296 (2005).

- Tun-Lin, W., Burkot, T., Kay, B. Effects of temperature and larval diet on development rates and survival of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti in north Queensland, Australia. Med Vet Entomol. 14 (1), 31-37 (2000).

- Richardson, K., Hoffmann, A. A., Johnson, P., Ritchie, S., Kearney, M. R. Thermal sensitivity of Aedes aegypti from Australia: empirical data and prediction of effects on distribution. J Med Ent. 48 (4), 914-923 (2011).

- Richardson, K. M., Hoffmann, A. A., Johnson, P., Ritchie, S. R., Kearney, M. R. A replicated comparison of breeding-container suitability for the dengue vector Aedes aegypti in tropical and temperate Australia. Austral Ecol. 38 (2), 219-229 (2013).

- Ross, P. A., et al. Wolbachia infections in Aedes aegypti differ markedly in their response to cyclical heat stress. PLoS Pathog. 13 (1), e1006006 (2017).

- Gjullin, C., Hegarty, C., Bollen, W. The necessity of a low oxygen concentration for the hatching of Aedes mosquito eggs. J Cell Physiol. 17 (2), 193-202 (1941).

- Axford, J. K., Ross, P. A., Yeap, H. L., Callahan, A. G., Hoffmann, A. A. Fitness of wAlbB Wolbachia infection in Aedes aegypti: parameter estimates in an outcrossed background and potential for population invasion. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 94 (3), 507-516 (2016).

- Degner, E. C., Harrington, L. C. Polyandry depends on postmating time interval in the dengue vector Aedes aegypti. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 94 (4), 780-785 (2016).

- Bentley, M. D., Day, J. F. Chemical ecology and behavioral aspects of mosquito oviposition. Ann Rev Entomol. 34 (1), 401-421 (1989).

- Wong, J., Stoddard, S. T., Astete, H., Morrison, A. C., Scott, T. W. Oviposition site selection by the dengue vector Aedes aegypti and its implications for dengue control. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 5 (4), e1015 (2011).

- Meola, R. The influence of temperature and humidity on embryonic longevity in Aedes aegypti. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 57 (4), 468-472 (1964).

- Faull, K. J., Williams, C. R. Intraspecific variation in desiccation survival time of Aedes aegypti (L.) mosquito eggs of Australian origin. J Vector Ecol. 40 (2), 292-300 (2015).

- McMeniman, C. J., O'Neill, S. L. A virulent Wolbachia infection decreases the viability of the dengue vector Aedes aegypti during periods of embryonic quiescence. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 4 (7), e748 (2010).

- Ross, P. A., Endersby, N. M., Hoffmann, A. A. Costs of three Wolbachia infections on the survival of Aedes aegypti larvae under starvation conditions. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 10 (1), e0004320 (2016).

- Carvalho, D. O., et al. Mass production of genetically modified Aedes aegypti for field releases in Brazil. J Vis Exp. (83), e3579 (2014).

- Benedict, M. The first releases of transgenic mosquitoes: an argument for the sterile insect technique. Trends Parasitol. 19 (8), 349-355 (2003).

- Lee, S. F., White, V. L., Weeks, A. R., Hoffmann, A. A., Endersby, N. M. High-throughput PCR assays to monitor Wolbachia infection in the dengue mosquito (Aedes aegypti) and Drosophila simulans. Appl Environ Microbiol. 78 (13), 4740-4743 (2012).

- Corbin, C., Heyworth, E. R., Ferrari, J., Hurst, G. D. Heritable symbionts in a world of varying temperature. Heredity. 118 (1), 10-20 (2017).

- Day, J. F., Edman, J. D. Mosquito engorgement on normally defensive hosts depends on host activity patterns. J Med Ent. 21 (6), 732-740 (1984).

- Gonzales, K. K., Hansen, I. A. Artificial diets for mosquitoes. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 13 (12), (2016).

- McMeniman, C. J., Hughes, G. L., O'Neill, S. L. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti disrupts mosquito egg development to a greater extent when mosquitoes feed on nonhuman versus human blood. J Med Ent. 48 (1), 76-84 (2011).

- Caragata, E. P., Rances, E., O'Neill, S. L., McGraw, E. A. Competition for amino acids between Wolbachia and the mosquito host, Aedes aegypti. Microb Ecol. 67 (1), 205-218 (2014).

- Suh, E., Fu, Y., Mercer, D. R., Dobson, S. L. Interaction of Wolbachia and bloodmeal type in artificially infected Aedes albopictus (Diptera: Culicidae). J Med Entomol. , (2016).

- Thangamani, S., Huang, J., Hart, C. E., Guzman, H., Tesh, R. B. Vertical transmission of Zika virus in Aedes aegypti mosquitoes. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 95 (5), 1169-1173 (2016).

転載および許可

このJoVE論文のテキスト又は図を再利用するための許可を申請します

許可を申請さらに記事を探す

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2023 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved