Aby wyświetlić tę treść, wymagana jest subskrypcja JoVE. Zaloguj się lub rozpocznij bezpłatny okres próbny.

Method Article

A New Application of the Electrical Penetration Graph (EPG) for Acquiring and Measuring Electrical Signals in Phloem Sieve Elements

W tym Artykule

Podsumowanie

Electrical Penetration Graph (EPG) is a well-established technique for studying the feeding behavior of stylet-bearing insects. Here we show a new application of EPG as a non-invasive tool for the acquisition of intracellular electrophysiology recordings of sieve elements (SEs), the cells that form the phloem vasculature in plants.

Streszczenie

Electrophysiological properties of cells are often studied in vitro, after dissociating them from their native environments. However, the study of electrical transmission between distant cells in an organism requires in vivo, artifact-free recordings of cells embedded within their native environment. The transmission of electrical signals from wounded to unwounded areas in a plant has since long piqued the interest of botanists. The phloem, the living part of the plant vasculature that is spread throughout the plant, has been postulated as a major tissue in electrical transmission in plants. The lack of suitable electrophysiological methods poses many challenges for the study of the electrical properties of the phloem cells in vivo. Here we present a novel approach for intracellular electrophysiology of sieve elements (SEs) that uses living aphids, or other phloem-feeding hemipteran insects, integrated in the electrical penetration graph (EPG) circuit. The versatility, robustness, and accuracy of this method made it possible to record and study in detail the wound-induced electrical signals in SEs of central veins of the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana1. Here we show that EPG-electrodes can be easily implemented for intracellular electrophysiological recordings of SEs in marginal veins, as well as to study the capacity of SEs to respond with electrical signals to several external stimuli. The EPG approach applied to intracellular electrophysiology of SEs can be implemented to a wide variety of plant species, in a large number of plant/insect combinations, and for many research aims.

Wprowadzenie

The ability to produce long-distance electrical signals is an advantageous trait of multi-cellular organisms that allows for efficient responses to external stimuli. This trait has evolved independently in plants and animals, and thus represents a case of convergent evolution. Given that electrical signals are coupled with important functions in animals such as neural transmission and muscle contraction, the molecular basis, mechanism of transmission, and function of stimulus-induced electrical signals in animals are subjects of intensive research. In contrast, stimulus-induced electrical signaling in plants has received little research attention. Although plants have no nerves or muscles, there seems to be enough evidence to assume that stimulus-induced electrical signals in plants play a key role in their responses to environmental factors.

The phloem, the living component of the plant vasculature, has been postulated as a major substrate for the transmission of stimulus-induced electrical signals, from stimulated/damaged to non-stimulated/undamaged areas2. The main cells in the phloem are the sieve elements (SEs), relatively simple, elongated cells. The ends of SEs are connected to other SEs, forming a continuous, low-resistance, sieve tube system that is spread throughout the plant. There are, however, very few studies on the electrical properties of these highly specialized cells. In these previous studies, researchers accessed SEs with either glass micro-electrodes3 or with glass electrodes that were coupled to plant-inserted stylets of aphids, after stylectomy (cutting)4. Glass microelectrodes are made from glass capillaries that are pulled at one end with heat into a fine tip of less than 1 µm in diameter, and then filled with a KCl solution. A Ag/AgCl or platinum wire, inserted into the KCl-filled glass electrode is then connected to the amplifier input, and a referent electrode is inserted into the bath surrounding the cell of interest, completing the circuit. This setup records the difference in potential between the extracellular referent electrode and the intracellular measuring electrode, i.e., the membrane potential of the cell5. With this method, Umrath made the first intracellular recording from a plant cell, using the algae Nitella6,7. Nitella is a relatively simple organism with large cells, and therefore amenable to intracellular electrophysiology experiments. In contrast, the insertion of intracellular glass electrodes into the small cells of multi-cellular, three-dimensional terrestrial plants is technically demanding, requires a highly skilled researcher, as well as sophisticated visualization, micromanipulation, and anti-vibration equipment. Although glass electrodes are suitable to record from superficial cells in plants, such as root epidermal cells8, intracellular recordings from cells deeply embedded in the plant's tissue, such as SEs, very likely cause damage-induced responses, confusing the results. In 1989, Fromm and Eschrich reported the use of an alternative method, called the 'aphid method', in which glass electrodes are coupled to aphid stylets after stylectomy4. The aphid method is minimally invasive, because flexible stylets do not cause tissue or cell damage as glass electrodes do. Aphid stylets are nature's great invention for plant penetration, and aphids are considerably more skilled than humans in finding SEs. Unfortunately, this aphid method is also highly demanding in terms of technical expertise and equipment. In addition, the success of each experiment that implements this technique depends entirely on the aphid being in feeding mode — with the stylet stably inserted into a SE, at the time of stylectomy. Thinking in retrospective, one can see that the odds of success of this technique could have been improved by adding to the experimental setup an instrument that allows identifying whether or not the aphid stylet is in the SE when applying stylectomy.

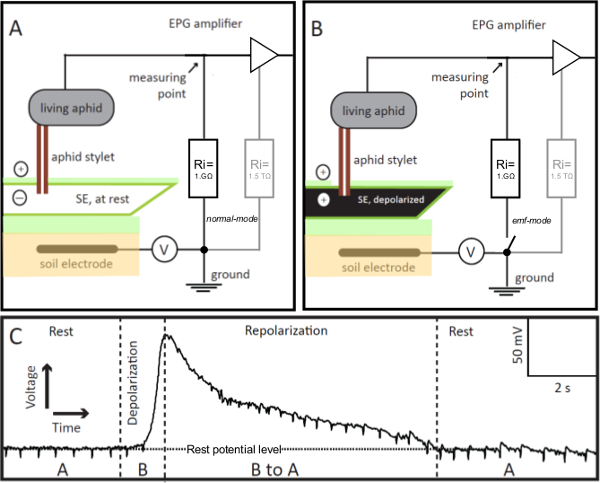

In 1964, McLean and Kinsey described an 'electronic monitoring system' for the study of the feeding behavior of aphids in real time9,10. In this system, the aphid and the stylet-penetrated plant were integrated into an electrical circuit. Later, in 1978, Tjallingii devised a modified version of the system, called the 'Electrical Penetration Graph' (EPG) system11,12. Whereas the original electronic monitoring system was sensitive to the resistance-originated potentials only, with the EPG system, the electromotive force (emf) originated potentials, i.e., generated in the plant or in the insect, could be recorded in addition to potentials arising from resistance (R) in the insect. This represents an important improvement, because both signal components, emf and R, provide biological relevant information on events during plant penetration by aphids. What makes the EPG pre-amplifier sensitive to the R-components is its relatively low input resistance of 1 GΩ, which is close to the average of the plant/aphid resistance. A small offset voltage (Figure 1, V) of approximately +100 mV is applied to the plant, which then is divided across plant and insect on one side, and the input resistance on the other. The voltages and their changes are measured at a point (Figure 1A,B) between the insect and the input resistor. Therefore, the R-components represent plant-aphid resistance modulations of the offset voltage, whereas the emf-components are a certain fraction of plant potentials at the stylet tip and potentials caused in the insect. The plant potentials — most relevant here — are mainly membrane potentials of the plant cells punctured by the aphid stylets. The insect potentials appear to be mainly streaming potentials caused by fluid movements within the two stylet canals, i.e., the food and the salivary canals; no internal nerve or muscle potentials are recorded in the EPG. In practice, the stylet tip functions as an electrode tip. All plant cells are negatively charged inside relative to the positive outside of the cell. The electrical current (i.e., the movement of charged ions in watery solution) flowing from the inside to the outside and vice versa is very limited due to the high resistance of the cell membrane. Normally the resting potential is kept constant. However, when negative ions move out or positive ions move in through the cell membrane, the membrane potential is reduced, i.e., it 'depolarizes'. Depolarization occurs in case of cell excitation. Ions then move in or out when specific ion channels in the membrane are opened or when the membrane is damaged and ions leak in and out. All cells have ion channels and pumps in the plasma membrane that bring the membrane potential to its resting level by restoring the original concentration of various ions inside the cell. The resting potential and its changes are emf components, and therefore, the EPG technique is suitable to measure them.

Figure 1. EPG-electrodes. The EPG-electrode is a living aphid integrated into the Electrical Penetration Graph (EPG) circuit, whose stylet is inserted into a sieve element (SE) in stable feeding mode. If the stylet-impaled SE is at rest (panel A), the voltage in the circuit, recorded by EPG, is stable and at the resting potential level (Panel C, Rest). If the SE is excited, its membrane depolarizes (panel B), which is visualized in the EPG as a gradual increase in voltage (panel C, Depolarization). As the ionic balance in the SE returns to rest, i.e., it repolarizes, the voltage recorded by EPG gradually decreases to the rest potential level (Panel C, Repolarization). In panel C, “A” and “B” refer to the scenarios shown in panels A and B, respectively. V = Adjustable offset voltage source. Ri = Input resistor. In parallel to the 1 GΩ external resistor, the amplifier has an internal (in the OpAmp) high 1.5 TΩ resistor (panels A and B, in gray). By remote control of the switch the EPG pre-amp can be changed from normal to emf-mode, which allows obtaining highly accurate voltage values. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

In the next section, we provide the reader with a basic protocol for performing EPG experiments that is valid for both insect-focused and plant-focused studies.

Protokół

1. Aphid Rearing

Note: The choice of plant and aphid species for EPG recordings depends on the research aim. For studies on Arabidopsis thaliana, the aphid Brevicoryne brassicae is appropriate.

- Rear B. brassicae aphids in a greenhouse on Brassica oleracea. Keep the plants used for aphid rearing in cages, in order to avoid contaminating other plants. Keep aphid-rearing plants and experimental plants (in our case B. oleracea and A. thaliana) in separate rooms, in order to avoid contamination of experimental plants with aphids.

- Transfer aphids to fresh plants about every 2 weeks, before causing significant plant damage, or reaching overpopulation. Transfer 10-20 adult aphids to a fresh rearing plant to initiate a new colony.

- Monitor rearing plants regularly for contamination by unwanted aphid species, other insect herbivores, aphid parasitoids, and fungi that may affect the health of the aphid colony.

- Collect adult, wingless aphids up to one week after their final molt for EPG recording.

- After the experiments, return the experimental plants that were not used to the growth chamber, as they often have some offspring that has been produced during the recording, which could inadvertently contaminate other plants.

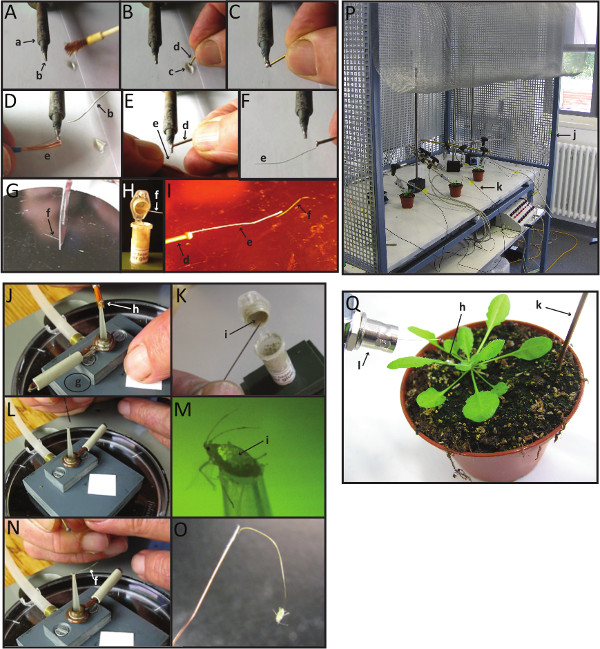

2. Insect Wiring for EPG Recording

- To make insect electrodes, obtain brass connector pins (nails, Ø 1.2 mm), thin copper wire (Ø 0.2 mm), very thin gold wire (Ø ca. 20 µm), water-based silver glue, a simple small soldering bolt with soldering fluid and resin-cored soldering wire, stereomicroscope with 10X magnification, small scissors or scalpel, two fine forceps, and a Styrofoam sheet or box. Note: A vortex mixer might be useful. Note: The step-by-step protocol to make electrodes is indicated in Figure 2.

- For aphid handling and glue application, obtain: a small and soft watercolor camelhair brush (size 2 or smaller) and insect pins such as those used for insect collections, although a fine sewing needle or toothpick may work as well. Step 4 shows how to start EPG recording.

- Step 1.

Note: Steps 1 and 2 below show how to prepare insect electrodes minus the aphid. Step 3 shows how to connect an aphid to the electrode. Vacuum fixation of the aphid is recommended during wiring, but not always required for slow moving species (e.g., B. brassicae).- Switch on the soldering bolt and melt some soldering wire at its tip (Figure 2A). Moisten the head of the brass connector pin with some soldering fluid (Figure 2B) and dip it into the melted soldering metal (Figure 2C).

- Apply a sheath of melted solder metal on one end of a 1-2 cm long piece of the thin copper wire (Figure 2D). Then bring the pin and copper wire together against the hot bolt (Figure 2E) and move them together away to cool and solidify (Figure 2F).

- Step 2.

- Thoroughly shake (or vortex) the vial with silver glue for several minutes until a smooth emulsion is shown. Cut (scissors or scalpel) a few pieces of the gold wire (of approximately 1.5 cm in length) on the object plate of the stereomicroscope (Figure 2G).

- Take a brass pin with soldered copper wire (made in section 2.3) and dip the free end of the copper wire into the small silver glue reservoir that will have gathered at inside the lid of the vial after opening it (Figure 2H). Note: Only a small droplet is needed.

- Move the glue-dipped end of the copper wire to the piece of gold wire, while lifting one end to avoid smearing the glue onto the stereomicroscope object plate. Try to overlap copper and gold wire for a few mm (Figure 2I), distributing the glue along the overlap of the two wires.

- Wait until the glue has been dried enough to keep the wires united. Check the glue contact after drying and add some fresh glue with a small pin or other piece of copper wire if some parts of the joined wires show glue-free parts.

- After the insect electrode is ready, store it, for example inserted into a piece of Styrofoam.

Note: The length of the gold wire will determine the freedom of movement of the aphid: if it is too short (less than 5 mm), the aphid may feel constrained and will not behave normally; if it is too long (>2 cm), the aphid will move freely. Aphids tend to move to the adaxial side of leaves, if allowed to. If the gold wire touches the leaf, the signal will be short-circuited.

- Step 3.

- The aphid may be kept in place by means of light suction, using a vacuum; in this case, install the suction device under the stereomicroscope. Place the suction opening in the center of the field.

- Thoroughly shake the vial with silver glue for several minutes (or vortex) until a smooth emulsion is formed. Collect an aphid with the small brush.

- Switch on the suction device and mount the aphid on the suction opening (Figure 2J), with the back of the abdomen turned to the experimenter. With the fine brush, remove any surface wax from the abdomen (abundant in cabbage aphids).

- Open the glue vial and wet a pin with a very small droplet of silver glue (Figure 2K). Apply the droplet of the silver glue onto the back of the aphid's abdomen (Figure 2L-M). Let this droplet completely dry during several minutes, vigorously shake the glue vial again and add a second droplet of silver glue on top of the first. Note: While the silver glue is an electrical conductor, it does not cause significant damage to the insect’s cuticle.

- After closing the glue vial, insert the free end of the gold wire into the wet droplet and keep the wire still while allowing the glue to dry completely (Figure 2N). Avoid smearing glue onto legs or antennae and discard an aphid if this has happened.

- Switch off the suction fixation device and carefully lift the insect (Figure 2O). If needed, use a fine brush to assist in the lifting of the aphid from the suction device.

Note: Wiring B. brassicae does not require a vacuum, as they can be wired on a piece of a precision laboratory tissue, the rough surface of which provides the aphid with enough grip so that it will not be lifted after applying a drop of wet glue to its abdomen. After glue drying one can lift the aphid from the tissue with the help of a fine brush. - Insert the brass pin with the wired insect into the Styrofoam and if needed, continue wiring all other insects to be used for the EPG recording session.

Note: These protocols for wiring aphids work well for us. The user may find his/her own method for wiring aphids.

- Step 4.

- Put plants in the Faraday cage (Figure 2P) on a non-conductive support: use Petri dishes or a plate of glass or plastic.

- Insert a plant electrode into the soil of each pot. Insert the brass pin of the wired insect into the input connector of the EPG pre-amplifier (Figure 2Q). Note: the soil electrode does not correspond to the ground electrode used in other electrophysiological techniques. It has the offset voltage needed to adjust and compensate for electrode polarization voltages.

- On the interface of the acquisition software Stylet+, with fixed sample frequency of 100 Hz, enter a filename, specify the recording time, and write text to specify details of the experiment (treatment, plant/insect species, etc.) in Comment lines 2 and 3.

- Lower the insects onto a suitable landing area of the plant and start the recording session by clicking on the Start button of the acquisition software (Stylet+) interface.

Note 1: a maximum of 8 channels can be used simultaneously in an EPG set up. One EPG-electrode or several EPG-electrodes per plant can be used.

Note 2: when the focus of the study is the aphid behavior, start the recording before plant access of the aphids to avoid missing the first plant penetration activities. - For studying the electrophysiological responses of SEs to stimuli, wait at least 10 min after the aphid has entered into phloem phase, in order to ensure that the aphid is in a sustained phloem ingestion phase, and that the signal baseline is stable. Only then, start any plant stimulation experiment.

Figure 2. Making EPG-electrodes with aphids or other hemipteran insects forelectrical penetration graph (EPG) recordings. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Panels A-I, steps required to prepare EPG-electrodes minus the aphid. First, melt a piece of soldering metal on the tip of a soldering bolt (A). Then, dip the head of the brass pin into a drop of soldering fluid (B), and contact it with the melted metal at the soldering bolt tip (C). Immediately after this step, contact the end of a copper wire to the tip of the soldering bolt, in order to glue it to the head of the brass pin (E-F). With a scalpel or a blade, cut a piece of the gold wire (G). Dip the free end of the copper wire (joined at the other end to the brass pin) on the silver glue (H), and quickly join the gold wire to it (I) before the silver dries up. The gold wire is an excellent conductor, and can be polarized. In reality, in the majority of the cases the polarization is too small to be detected, and if so, it can be compensated for with the offset voltage (V).

Panels J-O, steps needed to connect an aphid (or other hemipteran insect) to the electrode. First, carefully lift an aphid with a fine watercolor brush and place it on the opening of the vacuum suction device (J). Turn on the vacuum pump and cover the air valve hole with a piece of paper to apply suction. Dip the tip of the insect pin into the silver glue (K), and put a small glue droplet on top of the aphid's abdomen, under a stereomicroscope (L-M). Within the next ~20 sec, before the silver glue droplet on the aphid dries, insert the end of the gold wire of the insect electrode into the wet droplet of silver glue, and keep it in place for 1-3 min, until the silver glue has completely air-dried (N). At this point, disable suction by removing the piece of paper that covers the air valve hole of the suction device and carefully remove the aphid, from the suction device: lifting the aphid after wiring often requires some help by a fine brush (O).

Panel P shows an overview of the entire EPG set up inside the Faraday cage, and Panel Q shows an overview of the plant-aphid combination for EPG. See section 2 above for a more detailed explanation of this process.

Small letters are labels referring to the items that one needs to make EPG-electrodes: a: soldering bolt; b: melted soldering metal; c: soldering fluid; d: brass connector pin (nail); e: copper wire; f: Ø 18µm gold wire; g: suction device; h: aphid; i: water-based silver glue; j: Faraday cage; k: plant electrode; l: input connector (BNC) of the EPG pre-amplifier.

Wyniki

In a previous study, we implemented the EPG-electrode technique with the purpose of characterizing the electrical signals produced in SEs of the midvein during caterpillar attack1. The midvein is a preferred insertion site for conventional glass electrodes, as well as for glass-stylet electrodes, because it is SE-dense, and relatively robust, hence amenable to the fixation needed for implementing these techniques. Here, we took advantage of the versatility of the EPG electrode with the purpose of gathering ele...

Dyskusje

This article provides a detailed protocol for making Electrical Penetration Graph (EPG) recordings. The EPG technique is well established, with 100-200 active users worldwide, and it has been implemented for many studies on different topics, for example: a) host plant resistance to aphids and other stylet-bearing insects13; b) plant virus and pathogen transmission mechanisms14; c) insecticide mode of action, (toxicity and behavior changes)15; d) EPGs have even been useful to demonstrate t...

Ujawnienia

WFT launched EPG Systems as a retirement activity, and is affiliated with it financially.

Podziękowania

VSR was supported by an IIF Marie Curie Grant (WOUND IN EARTH, acronym for: Wound induced electrical signals in Arabidopsis thaliana).

Materiały

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Brass connector pins | EPG Systems/hardw.shop | Φ 1.2 mm | |

| Thin copper wire | EPG Systems/hardw.shop | approx. Φ 0.2 mm | |

| Thin gold wire | EPG Systems | Φ 18 µm | |

| Soldering fluid | hardware shop | matching the soldering wire | |

| Resin-cored soldering wire | hardware shop | ||

| Styrofoam | any | ||

| Water-based silver glue | EPG Systems | recipe in: www.epgsystems.eu | |

| Paper wipes | Kimberly-Clark | 5511 | |

| Soldering bolt | any | ||

| Stereomicroscope | Hund Wetzlar | minimum magnification is 10X | |

| Small scissors | Fine Science Tools | 14088-10 | |

| Scalpel | Fine Science Tools | 10050-00 | |

| Fine forceps | Fine Science Tools | 11231-20 | |

| Vortex | A. Hartenstein | L46 | |

| Watercolor brushes | any | Number 1 or 2 | |

| Air suction device | see description in: www.epgsystems.eu | ||

| Insect pins | any | No. 1 or 2 | |

| Solid table | |||

| Faraday cage | Hand made | ||

| Computer | Fujitsu Siemens | ||

| Data acquisition software | EPG Systems | Stylet+d | |

| Giga-4 (-8) Complete System | EPG Systems | ||

| includes the following: | |||

| Main control box with USB output | Di155/Di710 | 12/14 bit, rate 100 Hz (softw. fixed) | |

| EPG probes 4 (8) | 50x DC pre-amplifier | ||

| Swivel clamps on rod | |||

| DC power adaptor | bipolar, 230/115 VAC to -/+8 VDC | ||

| Plant electrodes and cables | |||

| Additional test and ground cables |

Odniesienia

- Salvador-Recatalà, V., Tjallingii, W. F., Farmer, E. E. Real-time, in vivo. intracellular recordings of caterpillar-induced depolarization waves in sieve elements using aphid electrodes. New Phytologist. 203 (2), 674-684 (2014).

- Van Bel, A. J., Knoblauch, M., Furch, A. C., Hafke, J. B. (Questions)n on phloem biology. 1. Electropotential waves, Ca2+ fluxes and cellular cascades along the propagation pathway. Plant Science. 181 (3), 210-218 (2011).

- Rhodes, J. D., Thain, J. F., Wildon, D. C. The pathway for electrical signal conduction in the wounded tomato plant. Planta. 200, 50-57 (1996).

- Fromm, J., Eschrich, W. Correlation of ionic movements with phloem unloading and loading in barley leaves. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 27, 577-585 (1989).

- Brette, R., Destexhe, A., Brette, R., Destexhe, A. Intracellular Recordings. Handbook of Neural Activity Measurement. , 44-91 (2012).

- Umrath, K. Untersuchungen über Plasma und Plasamstromung an Characeen. IV. Potentialmessungen an Nitella mucronata. mit besonderer Berücksichtingung der Erregungserscheinungen. Protoplasma. 9, 576-597 (1930).

- Umrath, K. Der Erregungsvorgang bei Nitella mucronata. Protoplasma. 17, 258-300 (1932).

- Carden, D. E., Walker, D. J., Flowers, T. J., Miller, A. J. Single-cell measurements of the contribution of cytosolic Na+ and K+ to salt tolerance. Plant Physiology. 131 (2), 676-683 (2003).

- Miles, P. W., McLean, D. L., Kinsey, M. G. Evidence that two species of aphid ingest food through an open stylet sheath. Experientia. 20 (10), 582 (1964).

- McLean, D. L., Kinsey, M. G. A technique for electronically recording aphid feeding and salivation. Nature. 202, 1358-1359 (1965).

- Tjallingii, W. F. Electronic recording of penetration behaviour by aphids. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. 24, 721-730 (1978).

- Tjallingii, W. F. Membrane potentials as an indication for plant cell penetration by aphid stylets. Entomologia Experimentalis et Applicata. 38, 187-193 (1985).

- Alvarez, E. E., et al. Comparative analysis of Solanum stoloniferum. responses to probing by the green peach aphid Myzus persicae. and the potato aphid Macrosiphum euphorbiae. Insect Science. 20 (2), 207-227 (2013).

- Carmo-Sousa, M., Moreno, A., Garzo, E., Fereres, A. A non-persistently transmitted virus induces a pull-push strategy in its aphid vector to optimize transmission and spread. Virus Research. 186, 38-46 (2014).

- Jacobson, A. L., Kennedy, G. G. Electrical Penetration Graph studies to investigate the effects of cyantraniliprole on feeding behavior of Myzus persicae. (Hemiptera: Aphididae) on Capsicum annuum. Pest Management Science. 70 (5), 836-840 (2014).

- Morris, G., Foster, W. A. Duelling aphids: electrical penetration graphs reveal the value of fighting for a feeding site. Journal of Experimental Biology. 211 (9), 1490-1494 (2008).

Przedruki i uprawnienia

Zapytaj o uprawnienia na użycie tekstu lub obrazów z tego artykułu JoVE

Zapytaj o uprawnieniaThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone