Aby wyświetlić tę treść, wymagana jest subskrypcja JoVE. Zaloguj się lub rozpocznij bezpłatny okres próbny.

Method Article

Monitoring Pedogenic Inorganic Carbon Accumulation Due to Weathering of Amended Silicate Minerals in Agricultural Soils.

* Wspomniani autorzy wnieśli do projektu równy wkład.

W tym Artykule

Podsumowanie

The verification method described here is adaptable for monitoring pedogenic inorganic carbon sequestration in various agricultural soils amended with alkaline earth metal silicate-containing rocks, such as wollastonite, basalt, and olivine. This type of validation is essential for carbon credit programs, which can benefit farmers that sequester carbon in their fields.

Streszczenie

The present study aims to demonstrate a systematic procedure for monitoring inorganic carbon induced by enhanced weathering of comminuted rocks in agricultural soils. To this end, the core soil samples taken at different depth (including 0-15 cm, 15-30 cm, and 30-60 cm profiles) are collected from an agriculture field, the topsoil of which has already been enriched with an alkaline earth metal silicate containing mineral (such as wollastonite). After transporting to the laboratory, the soil samples are air-dried and sieved. Then, the inorganic carbon content of the samples is determined by a volumetric method called calcimetry. The representative results presented herein showed five folded increments of inorganic carbon content in the soils amended with the Ca-silicate compared to control soils. This compositional change was accompanied by more than 1 unit of pH increase in the amended soils, implying high dissolution of the silicate. Mineralogical and morphological analyses, as well as elemental composition, further corroborate the increase in the inorganic carbon content of silicate-amended soils. The sampling and analysis methods presented in this study can be adopted by researchers and professionals looking to trace pedogenic inorganic carbon changes in soils and subsoils, including those amended with other suitable silicate rocks such as basalt and olivine. These methods can also be exploited as tools for verifying soil inorganic carbon sequestration by private and governmental entities to certify and award carbon credits.

Wprowadzenie

CO2 is a major greenhouse gas (GHG), and its concentration in the atmosphere is increasing continuously. Preindustrial global average CO2 was about 315 parts per million (ppm), and as of April 2020, the atmospheric CO2 concentration increased to over 416 ppm, hence causing global warming1. Therefore, it is critical to reduce the concentration of this heat-trapping GHG in the atmosphere. Socolow2 has suggested that to stabilize the concentration of atmospheric CO2 to 500 ppm by 2070, nine 'stabilization wedges' will be required, where each stabilization wedge is an individual mitigation approach, sized to achieve 3.67 Gt CO2 eq per year in emissions reduction.

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) is the main technology to reduce the CO2 from the atmosphere, as recommended by the Mission Innovation initiative, launched at the United Nations Climate Change Conference 20153. To capture atmospheric CO2, the three main storage options available are ocean storage, geological storage, and mineral carbonation4. Focusing on mineral carbonation, CO2 is stored by converting alkaline earth metals, mainly calcium- and magnesium-rich silicates, into thermodynamically stable carbonates for geological timeframes (over millions of years)5. For example, olivine, pyroxene, and serpentine group minerals have the potential to undergo mineral carbonation6; however, under normal conditions, these reactions are limited by slow reaction kinetics. Therefore, to speed up the process under ambient conditions, finely comminuted (crushed/milled) forms of these silicates can be applied to agricultural soils, a process referred to as terrestrial enhanced weathering7. Soil is a natural sink to store CO2, presently being a reservoir for 2500 Gt of carbon, which is thrice the atmospheric reservoir (800 Gt carbon)8. Pedogenic processes in soils and subsoils regulate atmospheric CO2 by two major natural pathways, namely the organic matter cycle and the weathering of alkaline earth metal minerals, affecting organic and inorganic carbon pools, respectively9.

It is estimated that almost 1.1 Gt of atmospheric CO2 is mineralized through chemical rock weathering annually10. Silicate rocks rich in calcium and magnesium (e.g., basalt) are regarded as the primary feedstocks for enhanced weathering9,11,12. Once crushed silicate-containing minerals are applied to agricultural fields, they begin to react with CO2 dissolved in soil porewater, concluding with the mineral precipitation of stable carbonates11,13. Olivine14,15, wollastonite (CaSiO3)13, dolerite, and basalt16 are among minerals which have demonstrated carbon sequestration potential through enhanced weathering in previous studies. Despite the greater availability, and hence possibly greater CO2 sequestration capacity, of magnesium silicates, there are concerns about their application for enhanced weathering in croplands due to their potential environmental impact as a result of Cr and Ni leaching and the possible presence of asbestiform particulates11,15,17,18. As a calcium-bearing silicate, wollastonite is herein highlighted as a prime candidate for this process due to its high reactivity, simple chemical structure, being environmentally benign as well as facilitating the production of carbonates due to the weaker bonding of Ca ions to its silica matrix12,19,20,21. Wollastonite that is mined in Kingston, Ontario, Canada, and is presently commercialized by Canadian Wollastonite for agricultural applications, does not contain elevated levels of hazardous metals. The worldwide wollastonite reserves are estimated to be over 100 Mt, with China, India, USA, Mexico, Canada, and Finland as the top productive countries22.

Enhanced weathering of silicate mineral is reckoned to promote soil health, notably crop yield increase and plant growth improvement, leading to the potential reduction in the application of synthetic fertilizers, which can further contribute to GHG emissions reduction11,18,19. Previous studies have reported that the application of Ca-rich silicate minerals to soils supplies basicity for neutralizing acidity in the soil medium, favoring crop production23,24,25. This also impedes toxic metals mobilization, susceptible to acidic conditions, and enhanced weathering could be useful for retarding erosion through soil organic matter increment11.

Equations 1-3 show how pedogenic carbon sequestration as inorganic carbonates is possible by amending soils with wollastonite. Ambient CO2 enters the soil through rainwater or is produced in soil by microbial activity degrading organic compounds. Once in contact with soil porewater, carbonic acid is formed, which dissociates to form bicarbonate and proton (Equation 1). In the presence of plants, root exudates, such as citric acid and maleic acid, are released, which also provide protons in the system. These protons facilitate the dissolution of wollastonite in the soil through releasing Ca ions and leaving behind amorphous silica (Equation 2). The released Ca ions ultimately react with the bicarbonate to precipitate as carbonates (crystalline calcite or other varieties, depending on geochemical conditions) (Equation 3). This formed calcium carbonate becomes part of the soil inorganic carbon (SIC) fraction26.

Ambient CO2 solvation:

2CO2(g) + 2H2O(l) ↔ 2H2CO3(aq) ↔ 2HCO3- + 2H+ (1)

Wollastonite dissolution (H+ from the dissociation of carbonic acid and root exudates):

CaSiO3(s) + 2 H+ → Ca2+ + H2O(l) + SiO2(s) (2)

Pedogenic inorganic carbonate precipitation:

Ca2+ + 2 HCO3- → CaCO3(s)↓ + H2O(l) + CO2(g) (3)

In our recent work, enhanced weathering through the application of wollastonite to agricultural soils, as a limestone-alternative amendment, has been found effective for CaCO3 precipitation in topsoil, both at laboratory and field scales, and over short (few months) and long (3 years) terms. In the field studies, chemical and mineralogical assessments have revealed that the SIC content increases proportionally to wollastonite application dosage (tonne·hectare-1)13. In laboratory studies, the mineralogical analysis showed the presence of pedogenic carbonate due to carbon sequestration19. Pedogenic carbonate formation in soil depends on several factors, most notably: topography, climate, surface vegetation, soil biotic processes, and soil physicochemical properties27. Our previous study23 determined the role of plants (a leguminous plant (green bean) and a non-leguminous plant (corn)) on wollastonite weathering and inorganic carbonate formation in soil. Our ongoing research on the pedogenic carbon formation and migration in soils and subsoils includes investigating the fate of soil carbonates in agricultural soil, first formed in topsoils due to mineral weathering at various depths and over time. According to Zamanian et al.27, the naturally occurring pedogenic carbonate horizon is found farther from the surface as the rate of local precipitation increases, with the top of this horizon commonly appearing between a few centimeters to 300 cm below the surface. Other ambient and soil parameters, such as soil water balance, seasonal dynamics, the initial carbonate content in parent material, soil physical properties, also impact the depth of this occurrence27. Thus it is of significance to sample soils to a sufficient depth at all opportunities to obtain an accurate understanding of the original and the incremental levels of SIC resulting from enhanced weathering of silicates.

At the field scale, an important limitation is the use of low application rates of silicate soil amendments. As there is limited knowledge on the effect of many silicates (such as wollastonite and olivine) on soil and plant health, commercial producers avoid testing higher application rates that could result in significant carbon sequestration. As a result of such low application rates, as well as the large area of crop fields, a research challenge commonly faced is to determine changes in SIC when values are relatively low, and to recover and isolate the silicate grains and weathering products from the soil to study morphological and mineralogical changes. In our past work, we reported on how physical fractionation of the wollastonite-amended soil (using sieving) enabled a better understanding of the weathering process, especially the formation and accumulation of pedogenic carbonates28. Accordingly, the higher contents of wollastonite and weathering products were detected in the finer fraction of soil, which provided reasonably high values during analyses, ensuring more precise and reliable results. The findings highlight the importance of using physical fractionation, through sieving or other segregation means, for reliable estimation of the sequestrated carbon accumulation in silicate-amended soils. However, the degree of fractionation could vary from soil to soil and from silicate to silicate, so it should be further researched.

Accurate measurement of SIC is critical for establishing a standard and scientific procedure that can be adopted by various researchers interested in analyzing the evolution of SIC and (and organic carbon) over time and depth of the soil. Such methodology enables farmers to claim carbon credit as a result of SIC formation in their field soils. The following protocol describes, in detail: (1) a soil sampling method to be used following soil silicate amendment, which accounts for the statistical significance of the analyzed soil data; (2) a soil fractionation method that improves the accuracy of quantifying changes in pedogenic inorganic carbonate pool as a result of enhanced silicate weathering, and (3) the calculation steps used to determine the SIC sequestration rate as a result of soil silicate amendment. For the purpose of this demonstration, wollastonite, sourced from Canadian Wollastonite, is assumed to be the silicate mineral applied to agricultural soils, and the agricultural soils are considered to be similar to those found in Southern Ontario's farmlands.

The procedure involving amending agricultural soil with wollastonite (e.g., determining the amount of wollastonite to apply per hectare, and the method to spread it over the soil) was described in our previous study13. The study area in our prior and present work is rectangular plots; therefore, the direct random sampling method is appropriate for such studies. This is a commonly used method owing to its low cost, reduced time requirement, and ability to provide adequate statistical uncertainty. Similarly, depending on the various field conditions and the level of statistical significance desired, zonal or grid sampling methods can also be used. Accuracy in soil sampling is essential to reduce statistical uncertainty as a result of sampling bias. When statistics are used, achieving less than 95% confidence (i.e., p < 0.05) is not considered "statistically significant." However, for certain soil studies, the confidence level may be relaxed to 90% (i.e., p < 0.10) owing to the number of uncontrolled (i.e., naturally varying) parameters in the field conditions that affect the general precision of measurements. In this protocol, two sets of samples are collected in order to investigate SIC content and other chemical, mineral, and morphological properties of the soil throughout its vertical profile.

Protokół

1. Soil sampling method and core collection

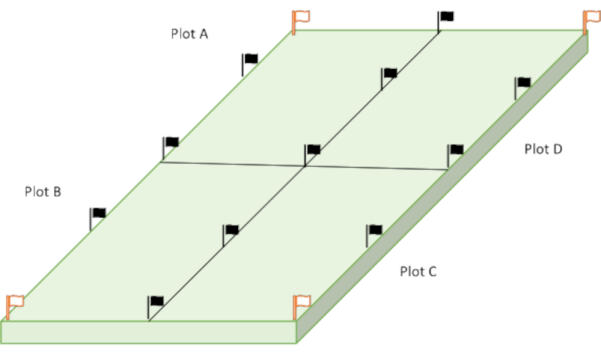

- Divide the mapped and a demarcated agricultural land area of interest into different plots based on the land elevation, historical crop yield, and/or land management strategy. Determine the leveling of each plot using a GPS receiver, classify crop yield based on historical farm records (below-average, average, above-average), and the land management strategy used for each plot (types of soil amendments used, if any). Place the flags at the boundaries of each plot to ease subsequent sampling.

NOTE: Figure 1 shows the sectioning of the rectangular area under study into four plots (A, B, C, D). Such an experimental design and information will be helpful to check the statistical significance of the analyzed data. Furthermore, it can be appropriate for irregular farmlands and be convenient for aligning sampling according to a parameter deemed necessary, from the orientation of crop rows to the direction of terrain, runoff, dominant wind, sun path, etc. These four plots were considered in order to facilitate a field filming campaign. - Use the directed random sampling method to collect cores across each plot. Subdivide each plot following a grid pattern into 25 sub-plots (Figure 2). Collecting 25 cores is above the traditionally minimum recommend number of cores (15-20).

Figure 1: Representation of the plots used for sample collection (each plot represents an area of 5 m × 10 m (totally four x 50 m2). Black flags delimit each plot boundary to ease sampling, and white flags mark locations for deep sampling. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 2: Sub-sectioning of each plot for collecting core samples (each sub-section represents an area of 1 m x 2 m), based on directed random sampling method. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

- Collect core samples from random points within each sub-plot, one per sub-plot. Use a soil probe or a soil core sampler to collect the soil core down to three depth zones of 0-15 cm, 15-30 cm, and 30-60 cm to account for the SIC variation with depth due to silicate soil amendment.

NOTE: Depending on the type of soil and the probe/sampler used, a different sampler may be required to collect the 30-60 cm sample. - Use an extendable auger (or similarly capable sampler) to collect deep soil samples from the white flag locations in Figure 1, down to additional three depth zones of 60-100 cm, 100-175 cm, and 175-250 cm. These samples account for the soil characterization variation within these depths as well as evaluate background SIC level in the investigated land area, down to the upper depth of the naturally occurring pedogenic carbonate horizon.

NOTE: Based on the local properties in site (e.g., depth of groundwater table), the deepest zone may be modified in different locations. - Transport the soil samples into buckets, one for each sampled depth at each plot. Hand-blend the soils in each bucket thoroughly. Place the portable moisture tester into the mixed soil sample. Wait until the moisture content fixes at a stable point on the gauge of the device. Press the holder button and record the value as the real-time moisture content of blended soils.

- Store the composite samples in sealed bags. Label bags properly with information about the plots (A, B, C, or D), the soil depth (0-15 cm, 15-30 cm, 30-60 cm, 60-100 cm, 100-175cm, 175-250 cm), and date of sampling.

2. Soil fractionation prior to chemical analysis

- Air-dry the soil samples as soon as possible after sampling to minimize the oxidation of soil carbon. For this, place the soil samples in cardboard boxes (2.5" x 3" x 3") and place the boxes in a drying cabinet at 50 °C for 24-48 h, until the soil is dry. Store the air-dried samples in sample bags until further analysis.

- Prior to soil fractionation, run the soil samples through a 2-mm sieve to remove large fragments of rocks and plant remains.

- Oven-dry the sieved soils by placing the samples in a muffle furnace maintained at 105 ± 2 °C for at least 15 h.

- For soil fractionation, place 1 kg of the oven-dried sample onto the top mesh of the sieve shaker consisting of different mesh sizes (710 to 50 µm). Shake the sieves at 60 rpm for 15 min. Pan fractions <50 µm are preferably used for analyses, as this is the pedogenic carbonate-enriched soil fraction.

NOTE: Other soil fractions can also be tested to yield additional data for verification of SIC accumulation due to enhanced weathering of amended silicates.

3. Pedogenic inorganic carbon sequestration determination

- To determine the inorganic carbon content of soil samples using calcimetry analysis, place 5 g of a sieved soil sample in an appropriate Erlenmeyer flask. Suspend the sample in 20 mL of ultrapure water. Add 7 mL of 4 M HCl to a small flat-bottomed glass test tube, then place this tube upright inside the flask using a pair of tweezers.

- Carefully attach the flask to the calcimeter by affixing the rubber stopper. The burette water levels on the calcimeter should have been previously adjusted as required, and blanks and CaCO3 standards should have been once run on the calcimeter as needed.

- Shake the flask, thereby knocking over the acid tube, until the water level in the burette reaches a constant value, and no bubbling is observed in the solution (this takes approximately 5 min).

- Calculate the CaCO3-equivalent (CaCO3(eqv)) content of the sample (g,CaCO3(eqv)·(kg,soil)-1) based on the volume change observed in the burette, and the blank and CaCO3 calibration values, using the appropriate calcimetry formula. SIC content is obtained by converting the g,CaCO3(eqv)·(kg,soil)-1 value into kg,CO2·(tonne,soil)-1 or kg,C·(tonne,soil)-1.

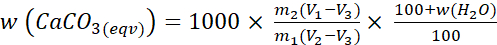

- Calculate the CaCO3(eqv) content of the sample using the below formula:

(4)

(4)

Where:

w (CaCO3(eqv)) = the carbonate content of the oven-dried soil

m1 = the mass of the test portion

m2 = the mean mass of the calcium carbonate standards

V1 = the volume of carbon dioxide produced by the reaction of the test portion

V2 = the mean volume of carbon dioxide produced by the calcium carbonate standards

V3 = the volume change in the blank determinations

w (H2O) = the water content of the dried sample

NOTE: steps 3.1 to 3.4 are conducted based on a standard protocol29.

- Calculate the CaCO3(eqv) content of the sample using the below formula:

- For measuring bulk density (BD) of soil ((tonne,soil)·m−3), place a sufficiently large aliquot of the oven-dried soil sample in a container with a known volume. Weigh the sample using a scale. The ratio of the dried weight to the volume of the sample is considered as BD.

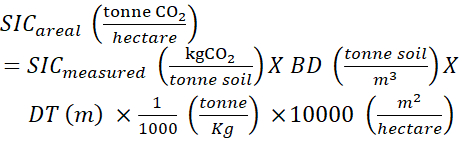

NOTE: The alternative devices for calculating "undisturbed bulk density" are introduced in the discussion. - Calculate the Areal SIC (kg,CO2·(hectare)−1) using the following formula:

(5)

(5)

Where:

A = the surface area

DT = depth thickness - Calculate the Total SIC (SIC 0-60 cm, kg,CO2·(hectare)−1) for each plot, using the areal SIC values obtained for each depth, as follows:

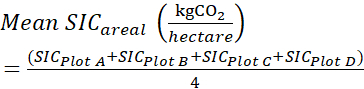

SICPlot A = SIC0-60 cm = SIC0-15 cm + SIC15-30 cm + SIC30-60 cm (6) - Add the Total areal SIC (SIC 0-60 cm, kg,CO2·(hectare)−1) content for each plot (A, B, C, D) investigated, and obtain the average mean as follows:

(7)

(7) - Divide the Mean areal SIC (kg,CO2·(hectare)−1) obtained from Eq. 7 by the application rate of silicate mineral/rock used for the soil amendment ((tonne, silicate)·(hectare)−1).

NOTE: This will provide the amount of pedogenic inorganic carbon sequestered in terms of kg of CO2 per tonne of silicate applied (kg, CO2·(tonne, silicate)−1). If a multi-year investigation is done, or a control plot without silicate amendment is present, this step needs to be modified to account for total sequestration and total amendment over a longer-term, or year-over-year values, or net pedogenic carbon sequestration.

Wyniki

The SIC content of soils can be determined using various methods, including an automated carbon analyzer or a calcimeter. The automated carbon analyzer for total soil carbon determination measures the CO2 pressure built-up in a closed vessel30. In calcimetry, the evolved volume of CO2 released after acidification, typically by the addition of concentrated HCl acid, of the carbonate-containing sample is measured. The calcimetry method is relati...

Dyskusje

Given that collecting samples from fertilized agricultural fields is usually difficult, it is suggested that samples should be collected before nutrient application. It is also advisable to avoid collecting samples from frozen fields. The sampling depth may vary in different areas depending on the ease of sampling over the vertical profile, and the depth of the water table. The selected soil sampling device is dependent on the soil structure and depth of interest33. While it is more convenient to ...

Ujawnienia

The authors have no conflict of interest.

Podziękowania

This work was supported by a Food from Thought Commercialization Grant, which is funded from the Canada First Research Excellence Fund. Canadian Wollastonite provided industrial financial support as part of this Grant.

Materiały

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Analytical scale | Sartorius | Quintix 224-S1 | Four decimals. |

| Calcimeter | Eijkelkamp | Model 08.53 | To determine the wt% CaCO3-equivalent in the sample. |

| Drying cabinet/muffle furnace | Thermo Scientific | F48055-60 | 50°C or 103 ± 2°C. |

| HCl | Fisher Scientific | A144S-500 | Reagent grade (36.5%-38.0%). |

| HNO3 | Fisher Scientific | T003090500 | Trace metal analysis grade (69.0%-70.0%) |

| Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (ICP-MS) | PerkinElmer | NexION | To determine the concentration of Ca in the microwave-digested soil. |

| Microwave digester | PerkinElmer | Titan | To digest soils in concentrated HNO3. |

| pH meter | Oakton | 700 | Calibrated with standard solutions before each set of measurements; temperature corrected to 25 °C. |

| Scanning Electron Microscope -Energy Dispersive Spectroscope (SEM-EDS) | Oxford | X-Max20 SSD | To determine the morphology of soil particulates. |

| Sieve shaker | Retsch | AS-200 | For soil fractionation. |

| Soil auger sampler | Eijkelkamp | 01-16 | Depths down to 700 cm. |

| Soil Dakota probe sampler | JMC | PN139 | Depths down to 100 cm. |

| Soil probe sampler | JMC | PN031 | Depths down to 30 cm. |

| Soil moisture meter | Extech | MO750 | Measure moisture content up to 50% |

| Wavelength Dispersive X-ray Fluorescence spectroscope (WDXRF) | Malvern Panalytical | Zetium | To characterize elemental composition of soil. |

| X-ray Diffraction analyzer (XRD) | Panalytical | Empyrean | To characterize mineralogicalbproperties of soil. |

Odniesienia

- Trends in atmospheric carbon dioxide. NOAA Available from: https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/ (2020)

- Socolow, R. Wedges reaffirmed. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists. 2011 (9), (2011).

- Mission Innovation. Joint launch statement. Mission Innovation. , (2015).

- Lackner, K. S., Brennan, S. Envisioning carbon capture and storage: Expanded possibilities due to air capture, leakage insurance, and C-14 monitoring. Climatic Change. 96 (3), 357-378 (2009).

- Lackner, K. S. A guide to CO2 sequestration. Science. 300 (5626), 1677-1678 (2003).

- Kwon, S., Fan, M., DaCosta, H. F. M., Russell, A. G. Factors affecting the direct mineralization of CO2 with olivine. Journal of Environmental Sciences. 23 (8), 1233-1239 (2011).

- Hartmann, J., et al. Enhanced chemical weathering as a geoengineering strategy to reduce atmospheric carbon dioxide, supply nutrients, and mitigate ocean acidification. Reviews of Geophysics. 51 (2), 113-149 (2013).

- Batjes, N. H. Total carbon and nitrogen in the soils of the world. European Journal of Soil Science. 47 (2), 151-163 (1996).

- Haque, F., Chiang, Y. W., Santos, R. M. Alkaline mineral soil amendment: A climate change stabilization wedge. Energies. 12 (12), 2299 (2019).

- Strefler, J., Amann, T., Bauer, N., Kriegler, E., Hartmann, J. Potential and costs of carbon dioxide removal by enhanced weathering of rocks. Environmental Research Letters. 13 (3), 34010 (2018).

- Beerling, D. J., et al. Farming with crops and rocks to address global climate, food and soil security. Nature Plants. 4 (3), 138-147 (2018).

- Lefebvre, D., et al. Assessing the potential of soil carbonation and enhanced weathering through Life Cycle Assessment: A case study for Sao Paulo State, Brazil. Journal of Cleaner Production. 233, 468-481 (2019).

- Haque, F., Santos, R. M., Chiang, Y. W. CO2 sequestration by wollastonite-amended agricultural soils-An Ontario field study. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control. 97, 103017 (2020).

- Ten Berge, H. F. M., et al. Olivine weathering in soil, and its effects on growth and nutrient uptake in ryegrass (Lolium perenne L.): a pot experiment. PloS One. 7 (8), 42098 (2012).

- Amann, T., et al. Enhanced weathering and related element fluxes-A cropland mesocosm approach. Biogeosciences. 17 (1), 103-119 (2020).

- Manning, D. A. C., Renforth, P., Lopez-Capel, E., Robertson, S., Ghazireh, N. Carbonate precipitation in artificial soils produced from basaltic quarry fines and composts: An opportunity for passive carbon sequestration. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control. 17, 309-317 (2013).

- Frazell, J., Elkins, R., O'Geen, A. T., Reynolds, R., Meyers, J. Facts about serpentine rock and soil containing asbestos in California. ANR Publication: University of California. , 8399 (2009).

- Kelland, M. E., et al. Increased yield and CO2 sequestration potential with the C4 cereal Sorghum bicolor cultivated in basaltic rock dust-amended agricultural soil. Global Change Biology. 26 (6), 3658-3676 (2020).

- Haque, F., Santos, R. M., Chiang, Y. W. Optimizing inorganic carbon sequestration and crop yield with wollastonite soil amendment in a microplot study. Frontiers in Plant Science. 11, 1012 (2020).

- Palandri, J. L., Kharaka, Y. K. A compilation of rate parameters of water-mineral interaction kinetics for application to geochemical modeling. National Energy Technology Laboratory-United States Department of Energy. , (2004).

- Schott, J., et al. Formation, growth and transformation of leached layers during silicate minerals dissolution: The example of wollastonite. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 98, 259-281 (2012).

- Brioche, A. S. Mineral commodity summaries-Wollastonite. US Geological Survey. , (2018).

- Haque, F., Santos, R. M., Dutta, A., Thimmanagari, M., Chiang, Y. W. Co-benefits of wollastonite weathering in agriculture: CO2 sequestration and promoted plant growth. ACS Omega. 4 (1), 1425-1433 (2019).

- Li, Y., Both, A. -. J., Wyenandt, C. A., Durner, E. F., Heckman, J. R. Applying Wollastonite to Soil to Adjust pH and Suppress Powdery Mildew on Pumpkin. HortTechnology. 29 (6), 811-820 (2019).

- Mao, P., et al. Phosphate addition diminishes the efficacy of wollastonite in decreasing Cd uptake by rice (Oryza sativa L.) in paddy soil. Science of the Total Environment. 687, 441-450 (2019).

- Hangx, S. J. T., Spiers, C. J. Coastal spreading of olivine to control atmospheric CO2 concentrations: A critical analysis of viability. International Journal of Greenhouse Gas Control. 3 (6), 757-767 (2009).

- Zamanian, K., Pustovoytov, K., Kuzyakov, Y. Pedogenic carbonates: Forms and formation processes. Earth-Science Reviews. 157, 1-17 (2016).

- Dudhaiya, A., Haque, F., Fantucci, H., Santos, R. M. Characterization of physically fractionated wollastonite-amended agricultural soils. Minerals. 9 (10), 635 (2019).

- Calcimeter manual. Eijlelkamp Soil & Water Available from: https://www.eijkelkamp.com/download.php?file=M0853e_Calcimeter_b21b.pdf (2020)

- ASTM. ASTM D4373 - Standard test method for rapid determination of carbonate content of soils. American Society of Testing of Materials. , (2014).

- Schönenberger, J., Momose, T., Wagner, B., Leong, W. H., Tarnawski, V. R. Canadian field soils I. Mineral composition by XRD/XRF measurements. International Journal of Thermophysics. 33 (2), 342-362 (2012).

- Versteegh, E. A. A., Black, S., Hodson, M. E. Carbon isotope fractionation between amorphous calcium carbonate and calcite in earthworm-produced calcium carbonate. Applied Geochemistry. 78, 351-356 (2017).

- Soil Sampling. LSADPROC-300-R4. EPA Available from: https://www.epa.gov/sites/production/files/2015-06/documents/Soil-Sampling.pdf (2020)

- Smith, P., et al. How to measure, report and verify soil carbon change to realize the potential of soil carbon sequestration for atmospheric greenhouse gas removal. Global Change Biology. 26 (1), 219-241 (2020).

- . Measuring soil carbon change: A flexible, practical, local method Available from: https://soilcarboncoalition.org/measuring-soil-carbon-change-flexible-practical-local-method/ (2021)

- Haque, F., Santos, R. M., Chiang, Y. W. Using nondestructive techniques in mineral carbonation for understanding reaction fundamentals. Powder Technology. 357, 134-148 (2019).

- Han, X., et al. Understanding soil carbon sequestration following the afforestation of former arable land by physical fractionation. Catena. 150, 317-327 (2017).

- Jagadamma, S., Lal, R. Distribution of organic carbon in physical fractions of soils as affected by agricultural management. Biology and Fertility of Soils. 46 (6), 543-554 (2010).

- Walter, K., Don, A., Tiemeyer, B., Freibauer, A. Determining soil bulk density for carbon stock calculations: a systematic method comparison. Soil Science Society of America Journal. 80 (3), 579-591 (2016).

- Huijgen, W. J. J., Witkamp, G. -. J., Comans, R. N. J. Mechanisms of aqueous wollastonite carbonation as a possible CO2 sequestration process. Chemical Engineering Science. 61 (13), 4242-4251 (2006).

- Bughio, M. A., et al. Neoformation of pedogenic carbonates by irrigation and fertilization and their contribution to carbon sequestration in soil. Geoderma. 262, 12-19 (2016).

- Carmi, I., Kronfeld, J., Moinester, M. Sequestration of atmospheric carbon dioxide as inorganic carbon in the unsaturated zone under semi-arid forests. Catena. 173, 93-98 (2019).

- Washbourne, C. L., Lopez-Capel, E., Renforth, P., Ascough, P. L., Manning, D. A. C. Rapid removal of atmospheric CO2 by urban soils. Environmental Science and Technology. 49 (9), 5434-5440 (2015).

Przedruki i uprawnienia

Zapytaj o uprawnienia na użycie tekstu lub obrazów z tego artykułu JoVE

Zapytaj o uprawnieniaPrzeglądaj więcej artyków

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone