Ostracism: Effects of Being Ignored Over the Internet

Przegląd

Source: Peter Mende-Siedlecki & Jay Van Bavel—New York University

Social ostracism is defined as being ignored and excluded in the presence of others. This experience is a pervasive and powerful social phenomenon, observed in both animals and humans, throughout all stages of human development, and across all manner of dyadic relationships, cultures, and social groups and institutions. Some have argued that ostracism serves a social regulatory function, which can enhance group cohesion and fitness by removing unwanted elements.1 As such, the feeling of ostracism can serve as a warning to alter one’s behavior, in order to rejoin with the group.2

Research in social psychology has focused extensively on the affective and behavioral consequences of social ostracism. For example, individuals who have been ostracized report feeling depressed, lonely, anxious, frustrated, and helpless,3 and while they may now evaluate the source of their ostracism more negatively, they will also often try to ingratiate themselves to them.2 Furthermore, it has been speculated that the fear of ostracism is ultimately driven by a strong need to belong and to feel included, and serves as a social pressure leading to conformity, compliance, and impression management.4

In a model developed by Williams (1997), ostracism uniquely targets four core needs— belonging, self-esteem, control, and meaningful existence—triggering negative mood, anxiety, physiological arousal, and hurt feelings.5 In return, to defend against such psychological discomfort, ostracized individuals may attempt to cope by reinforcing these core needs. For example, they may attempt to visibly conform to group norms to reestablish their place amongst the collective.

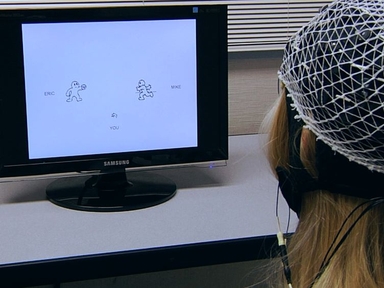

Procedura

1. Recruiting Participants

- Conduct a power analysis and recruit a sufficient number of participants (approximately 20/group) to cover six different experimental conditions, and, if desired, two additional control conditions (Table 1).

| In-Group | Out-Group | Mixed-Group | ||