需要订阅 JoVE 才能查看此. 登录或开始免费试用。

Method Article

从脑边缘和Mesocortical多巴胺奖赏网站继朴素的糖和脂肪摄入大鼠c-fos激活的同时检测

* 这些作者具有相同的贡献

摘要

这项研究的目的是通过使用蜂窝的c-fos的激活来测量大鼠的脂肪和糖新颖摄入后多巴胺途径和终端站点同步变化划定一个可靠免疫组织学技术,以确定奖励相关的分布式脑网络。

摘要

本研究采用细胞的c-fos的激活来评估脂肪和糖对大鼠脑内多巴胺(DA)的新途径摄入的影响。糖和脂肪摄入量是由他们天生的景点,以及了解到的喜好调节。脑多巴胺,特别是内消旋 - 边缘和从腹侧被盖区(VTA)内消旋 - 皮质突起,已经牵涉在这两个未学习并了解到响应。分布式脑网络,其中的几个位点和发射机/肽系统交互的概念,已提出调解适口食物摄入量,但有证据有限经验证明这种行动。因此,糖的摄入引起从个体VTA多巴胺投影区,包括伏隔核(NAC),杏仁核(AMY)DA释放和增加的c-fos的样免疫反应(FLI)和内侧前额叶皮质(mPFC的)以及背侧纹状体。此外,选择性多巴胺受体拮抗剂的集中管理到这些网站Ş差异减少糖类和脂肪引起的空调味的喜好采集和表达。一种方法,借以确定这些网站是否响应糖或脂肪摄入互动作为分布式脑网络将同时评估是否对VTA及其主要mesotelencephalic DA投影区域(前度和伏隔核的infralimbic内侧前额叶皮质,核和壳,基底外侧和中央皮质,内侧AMY)以及背侧纹状体会显示协调,口服后,无条件的摄入玉米油(3.5%),葡萄糖(8%),果糖(8%)和糖精的同时FLI激活(0.2 %)的解决方案。这种方法在鉴别同时使用到相关的大脑部位细胞的c-fos的激活,研究中啮齿类动物的可口食物摄取奖励有关学习的可行性了成功的第一步。

引言

脑内多巴胺(DA)已通过牵连到可口的糖的摄入量响应中央提出的享乐1,2,努力有关的3和习惯为基础的行动4,5机制。在这些效应牵连主DA通路起源于腹侧被盖区(VTA),和项目到伏隔核(NAC)芯和壳,基底外侧和中央皮质内侧杏仁核(AMY),以及前度和infralimbic内侧前额叶皮层(内侧前额叶皮质)(查看评论6,7)。该VTA有牵连的蔗糖摄入量8,9,和DA释放后观察糖的摄入量在10-15 NAC,AMY 16,17和内侧前额叶皮质18-20。脂肪的摄入量也刺激多巴胺释放的NAC 21,另有丰富DA投影带的背侧纹状体(尾状核)已与DA介导的喂养22,23也被相关。凯利24-27提出,这些多项目该DA介导系统的离子区形成通过广泛而亲密互连28-34集成和交互的分布式网络的大脑。

除了DA D1和D2受体拮抗剂来减少糖35-37和脂肪38-40的摄取的能力,DA信令也已牵涉于介导糖和脂肪以产生调节味道偏好(CFP)的能力41- 46。一个DA D1受体拮抗剂进入NAC,AMY或内侧前额叶皮质47-49显微注射消除CFP的收购胃内引起的葡萄糖。而无论是DA D1或D2受体拮抗剂显微注射到内侧前额叶皮质消除收购果糖CFP 50,收购和果糖CFP表达的差异由NAC和AMY 51,52 DA受体拮抗剂阻断。

在c-fos技术53,54已被用来研究神经活化法制由可口的摄入和神经激活ñ诱导。术语"C-fos的激活",将整个手稿中使用,并且通过增加的c-Fos蛋白的转录神经元去极化期间可操作限定。蔗糖摄取在中央AMY核增加fos的样免疫反应(FLI),所述VTA以及外壳,但不是核心,在NAC 55-57的。而糖水摄取量假喂养大鼠的AMY和NAC显著上升FLI,但不是VTA 58,胃内蔗糖或葡萄糖输注显著的NAC和AMY 59,60中央和基底外侧核增加FLI。重复加入蔗糖至预定食物访问在mPFC的增加FLI以及在NAC壳和芯61。蔗糖浓度降档模式显示,最大的FLI增加发生在基底AMY和NAC,但不是VTA 62。继空调,糖有关的自然雷瓦灭绝RD行为的基底AMY和NAC 63增加FLI。此外,配对糖可用性达到了口气导致口气随后在基底64 AMY增加FLI水平。高脂肪的摄入量也NAC和内侧前额叶皮质部位增加65-67 FLI。

大多数先前引用的研究中单个位点,不提供关于奖赏相关分布式大脑网络24-27的识别信息检测上的c-fos的激活糖和脂肪的效果。此外,许多研究也没有描绘在NAC(核和壳),AMY(基底和中央皮质内侧)和内侧前额叶皮质的子区域的相对贡献(前度和infralimbic)可能潜在的被检查优势出色的空间,在C-FOS映射68个单细胞的决议。我们的实验室69最近使用的c-fos的激活和同时测量改建的VTA DA通路及其亲jection区(NAC,AMY和内侧前额叶皮质)大鼠脂肪和糖的摄入小说之后。本研究描述的程序和方法步骤,同时分析是否急性暴露六个不同的解决方案(玉米油,葡萄糖,果糖,糖精,水和脂肪乳剂控制)在NAC,AMY的子区域将差异激活FLI,内侧前额叶皮质以及背侧纹状体。这种差异同时检测系统允许的每个站点和决心FLI显著效果的确认,是否与相关网站的变化密切相关,从而为分布式网络的脑支持24-27日在一个特定的站点变化。这些经过测试的程序是否VTA中,前度和infralimbic内侧前额叶皮质的NAC的核心和壳,以及基底和中央皮质,内侧AMY)以及背侧纹状体会显示协调,口服后,无条件的摄入同时FLI激活葡萄糖(8%),果糖(8%),玉米油(3.5%)和糖精(0.2%)的解决方案。

研究方案

这些实验方案已获得批准的机构动物护理和使用委员会证明所有的主体和程序均符合健康指南护理全国学院和实验动物使用。

1.主题

- 购买和/或品种雄性SD大鼠(260 - 300克)。

- 房子只单独在铁丝网笼子里。保持他们与大鼠饲料和水可随意 12:12小时的光/暗周期。

- 分配适当的样本大小(例如 ,N≈6 - 8)随机分组。

2.测试仪器和收容程序

- 使用校准的离心管用橡胶塞和一个45°角金属吸管,以提供精确的测量(±0.1毫升)所提出的解决方案。通过拉紧金属弹簧它们固定到饲养笼,以允许校准的能见度。

- 限制粮食配给(〜大鼠的15 /克/天),以减轻重量,以它们的原始体重的85%,以增加动力消耗的解决方案。注:减重应该采取3之间 - 天5。

- 在1小时的会话四天提供0.2%的糖精的训练前溶液(10毫升)以最大化大鼠将与短(少于1分钟)延迟采样随后的测试解决方案的可能性。

- 由溢出几滴确认通过离心管流动。

- 在每次会议结束后称取管获得的摄入量的测量。

- 执行在接收六溶液1子组在第五天的进气试验(10毫升,1小时):a)水,二)新颖味(0.05%樱桃香料)0.2%糖精,C)8%果糖,D)8 %葡萄糖,E)为3.5%的玉米油悬浮于0.3%黄原胶,和f)0.3%的黄原胶。

- 确保营养解决方案等热量;因此,3.5%的玉米油浓度等热量至8%的糖溶液。

- 确保日在短的等待时间(小于1分钟)的大鼠的样品溶液。如果这个要求不能满足,则丢弃从研究的课题。

3.组织准备

- 由最初暴露于每个测试溶液后的戊巴比妥90分钟腹膜内注射麻醉各动物。确认动物被适当地证明该动物不再响应这样的反射,撤退到脚捏,闪烁下的角膜直接压力或摇头来深耳廓刺激麻醉。

- 如前面所述69灌注transcardially每个动物。

- 麻醉大鼠的戊巴比妥钠(65毫克/千克)的过量,取出肋骨和揭露胸部免费进入心脏69。

- 放置针在左心脏瓣膜的先端,并切断腔静脉。施用接着是磷酸盐缓冲的固定剂共磷酸盐缓冲液(PBS,〜180ml)中ntaining 4%多聚甲醛(〜180毫升)中。

- 确保动物实际被正确地通过检查液体是否正在离开其他腔,如鼻,口,和生殖器区域灌注。注:多聚甲醛适当固定将大肌肉运动陪同。如果这种情况不会发生,直到发生这种反应重新调整针。

- 快速通过削减皮毛和皮肤从头骨上卸下从头骨的大脑。用咬骨钳破解,并动起了脑筋,从后到前去除骨头。最初的工作在下面和小脑后面的区域,确保咬骨钳是骨和脑膜软脑膜之间。一旦头骨的顶部和侧面被去除,用小刮刀从底座提起大脑,并剪断颅神经的小剪刀。小心不要损伤大脑在试图消除骨。

- 固定在4%多聚甲醛溶液的大脑在4℃下过夜。放置的大脑中有30%的蔗糖/ 70%PBS中在室温下溶液中,直至它们沉降在容器的底部。

- 阻止脑

- 取出大脑切割横向尾椎嗅球的延髓一部分。

- 取出大脑在小脑和脑桥水平横向切割的尾的部分。

- 冠装入大脑与固定在滑动切片机的阶段尾椎部位,切冠状切片(40微米)通过内侧前额叶皮质(2.86 - 2.20毫米喙前囟门),南汽芯和外壳和背侧纹状体(+ 1.76 - 1.60毫米喙前囟门),艾米(-2.12 - -2.92毫米尾鳍前囟)和VTA(-5.20 - -5.60毫米尾鳍前囟)。使用大鼠脑图谱70指导。

- 收集自由浮动切片到充满PBS中,以便最终免疫组织化学分析71 24孔板的各个孔中。用封口膜密封24,我们LL板以确保PBS不会在容器蒸发和干涸大脑。储存在4℃的脑组织。

4,c-fos程序(从71改编)

- 对待每个部分用5毫升5%正常山羊血清和0.2%的Triton X-100的PBS中1小时。

- 孵育初级抗体处理过的部分(兔抗c-fos和1:5000)4℃36小时在含有1毫升的PBS的孔中。

- 冲洗切片3倍,用PBS(5毫升),每次10分钟。

- 在RT 2小时在含有1毫升的PBS的孔中:;具有第二抗体孵育(200 1生物素化的山羊抗兔)。

- 漂洗,每次10分钟的PBS每个部分3×(5毫升)中。

- 孵育在附带在一个5毫升的PBS Avadin DH(100微升)和生物素化辣根过氧化物酶的H(100微升)构成试剂盒的市售抗生物素蛋白 - 辣根过氧化物酶混合物2小时的漂洗部分。

- 再冲洗部3X的PBS(5ml)中,每次10分钟。

- 反应在0.0015%H 2 O 2的存在下进行5用0.05%二氨基联苯胺(DAB)的章节- 10分钟,这取决于组织在含有5毫升DAB溶液的孔中的反应性。

- 双击标签VTA部分。在PBS(5毫升)在4℃过夜:用酪氨酸羟化酶(TH)抗体(2,000兔抗大鼠TH,1)孵育它们。

- 冲洗切片3倍于PBS(5ml)中,每次10分钟。

- 在室温下在PBS中(5毫升)处理2小时:;具有第二抗体孵育(200 1生物素化的山羊抗兔)。

- 冲洗切片3倍于PBS(5ml)中,每次10分钟。

- 通过使用二次抗体 - 过氧化物酶复合物可视化的抗体。用0.05%DAB的组合,0.3%的硫酸镍溶液进行反应,5 - 10分钟,这取决于组织在含有5毫升的DAB /的NiCl溶液的孔中的反应。

- 确保DAB溶液的颜色是乳白色浅绿色从中用0.3%的硫酸镍的反应。如果溶液是太绿,然后将反应将太暗。

- 安装所有章节到明胶涂层的幻灯片。让他们干通宵,然后盖玻片用甲苯基础的解决方案(TBS)几滴。

- 代码幻灯片,使实验条件是未知的观察员。

5.测定c-fos的免疫反应计数

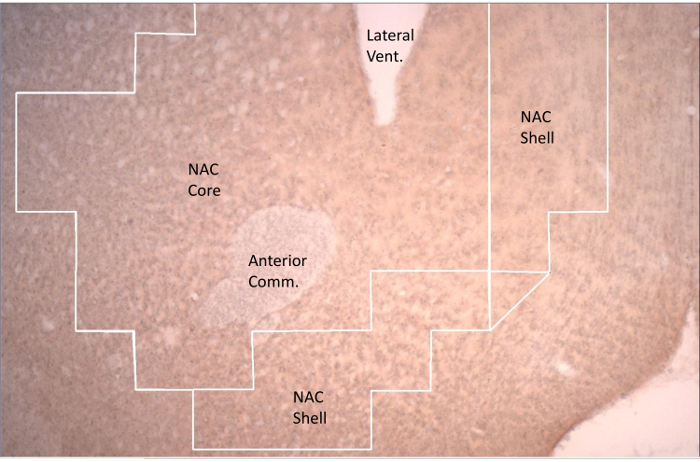

- 对分配公正的观察员来算感兴趣这些区域(ROI)的Fos阳性神经元:前度内侧前额叶皮质,infralimbic内侧前额叶皮质,NAC核心,NAC壳,基底核AMY,中央皮质内侧AMY,背侧纹状体和VTA。划定的c-Fos的免疫反应是否存在于TH +和TH-细胞中的VTA。 图1提供了从显微镜NAC的屏幕捕获的图像。

按网格由c-fos计数制成轮廓利益图1伏隔核的代表科(NAC)显示区域。NAC的外壳内侧和腹部发现了NAC的核心。在NAC核心环绕前连合(前通信)。侧脑室(横向通风)的腹侧程度是可见的。 请点击此处查看该图的放大版本。

- 在所有的测试条件分析每个通用于所有动物的网站至少有三个有代表性的切片。

- 使用软件并在光学显微镜通过跟踪轮廓( 图1)以分析每个ROI的整个区域。

- 对于给定的网站,打开应用程序,并单击收购下拉菜单中,点击"实时图像"。带来的投资回报率成为关注的焦点,并点击屏幕来建立一个参考点。然后TR王牌使用网格作为指导所选择的脑区域。一旦跟踪完成后,细胞计数(步骤5.3.1.1 - 5.3.1.3)。

- 双击软件图标。转到菜单栏,点击"获取",然后选择"实时图像"。带来的投资回报率成为关注的焦点,并点击屏幕来建立一个参考点。

- 转到网格工具栏,然后单击"显示网格"和"使用网格标签"。外形与预定的一丝投资回报率。

- 计算所有细胞的每个ROI区域中,在左侧栏选择一个"+",以保持c-fos的细胞计数。点击每个单元单独注册计数。当一个定义暗红色圆圈观察( 图1)考虑为阳性的c-fos基因的细胞。

- 重复此过程为每个站点。

- 记录在实验室笔记本和电脑供日后分析的计算。转到菜单栏中,单击"文件","保存数据文件"保存跟踪和计数。

- 对于给定的网站,打开应用程序,并单击收购下拉菜单中,点击"实时图像"。带来的投资回报率成为关注的焦点,并点击屏幕来建立一个参考点。然后TR王牌使用网格作为指导所选择的脑区域。一旦跟踪完成后,细胞计数(步骤5.3.1.1 - 5.3.1.3)。

- 保证两个不知情的评估者的评判间的可靠性(使用计数的相关性),使各ROI每一节总是超过0.8。

6.统计

- 使用重复测量方差分析的1路分析比较,3天1 2和4 69的糖精摄入量在评估前四天基线糖精摄入量。

- 比较糖精摄入量(第4天),使用一个随机块双因子ANOVA 69的六组试验摄入量(第5天)。

- 使用杜克比较(P <0.05),以确定个人显著影响69。

- 确定评判间的可靠性,然后用普通观察者的计数。

- 平均C-FOS计数为每个站点69的三个有代表性的切片。

- 执行由六种溶液(3.5%的玉米油,8%的葡萄糖,8%果糖,0.2%调味糖精,XA摄入诱导的c-fos的激活的单因素方差分析对于perilimbic内侧前额叶皮质69 nthan胶控制和水)。

- 六组的infralimbic内侧前额叶皮质,NAC核心,NAC外壳,基底AMY,中央皮质内侧AMY,VTA和背侧纹状体的重复平行分析。使用杜克比较(P <0.05),以显示个别显著影响69。

- 比较玉米油的摄入量与饮水量都和进它的悬挂剂,黄原胶。比较取水和非营养性甜味剂,糖精的摄取都果糖和葡萄糖摄入。

- 建立使用邦费罗尼ř相关(P <0.05)是否观察每个站点的溶液摄入和c-fos激活之间显著关系。

- 比较系统地在perilimbic和infralimbic前额叶皮层的3.5%,玉米油组中的每个动物的c-fos的计数。

- 重复每对六个站点的系统并行分析(VTA,背侧纹状体,infralimBIC内侧前额叶皮质,perilimbic内侧前额叶皮质,NAC核心,NAC外壳,基底AMY,中央皮质内侧AMY)为3.5%,玉米油。

- 重复上述六个站点的系统并行分析其他五个实验条件的摄入量(8%葡萄糖,8%的果糖,0.2%调味糖精,黄原胶控制和水)。

- 取的一个事实,即一个溶液条件中的相同动物通过跨解决方案,并使用邦费罗尼每种溶液中确定的c-fos的激活之间显著关系在所有站点评价优点ř相关(P <0.05)。

结果

下面描述的所有代表性结果先前已发表69,并在此处重新提出支持"概念验证"中指示的技术的有效性。

解决方案摄入量

在基线糖精摄入显著差异观察到在第一四天所有动物(F(3108)= 57.27,P <0.001)与摄入量(第1天:1.3(±0.2)毫升;第2天:3.9(±0.4)毫升;第3天:5.9(±0.6)毫升;第4天:7.1(±0.6)毫?...

讨论

这项研究的目的是利用细胞的c-fos的技术来确定源(VTA)和前脑投射目标DA奖励相关的神经元(NAC,AMY,内侧前额叶皮质)的脂肪和糖的新型摄入后同时激活大鼠。本研究是此前69发表的一项研究协议的详细描述。据推测,在VTA,其主要投影区域的前度和infralimbic mPFC的,在NAC的核和壳和基底外侧和中央皮质内侧AMY,以及背侧纹状体将充当分布式脑网络24 -27,并显示协调下同时FLI小?...

披露声明

作者有没有竞争经济利益。

致谢

由于戴安娜卡萨-Culaki,克里斯塔尔桑普森和神学Karagiorgis为他们在这个项目上努力工作。

材料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Equipment | |||

| Sprague-Dawley rats | Charles River Laboratories | CD-1 | |

| Wire Mesh Cages | Lab Products, Seaford, DE | 30-Cage rack | |

| Rat Chow | PMI Nutrition International | 5001 | |

| Taut Metal Spring | Lab Products, Seaford, DE | n/a | |

| Rat Weighing Scale | Fisher Scientific Company | n/a | |

| Nalgene Centrifuge Tubes | Lab Products, Seaford, DE | 10-0501 | |

| Rubber Stopper | Lab Products, Seaford, DE | n/a | |

| Metal Sippers | Lab Products, Seaford, DE | n/a | |

| Saccharin | Sigma Chemical Co | 82385-42-0 | |

| Kool-Aid, Cherry | Kool-Aid | Commerical | |

| Kool-Aid, Grape | Kool-Aid | Commercial | |

| Fructose | Sigma Chemical Co | F0127 | |

| Glucose | Sigma Chemical Co | G8270 | |

| Corn Oil | Mazzola | Commerical | |

| Xanthan Gum | Sigma Chemical Co | 11138-66-2 | |

| Sliding Microtome | Microm International | n/a | |

| Neurolucida Camera | MBF Bioscience | Software application | |

| Gelatin-coated Slides | Fisher Scientific Company | 12-550-343 | |

| Cover glass | Fisher Scientific Company | 12-545-M | |

| Golden Nylon Brushes | Loew-Cornell | 2037 | |

| Natural Hair Sable | Loew-Cornell | 2022 | |

| 24 Well Plates | Fisher Scientific | 3527 | |

| 6 Well Plates | Fisher Scientific | 3506 | |

| 1 L Pyrex bottles | Fisher Scientific | 1395-1L | |

| Tissue insert (tissue strainer) | Fisher Scientific | 7200214 | |

| Eagle pipettes | World Precision Instruments | E10 for 1-10μl | |

| Eagle pipettes | World Precision Instruments | E100 for 20-100μl | |

| Eagle pipettes | World Precision Instruments | E200 for 50-200μl | |

| Eagle pipettes | World Precision Instruments | E1000 for 100-1000μl | |

| Eagle pipettes | World Precision Instruments | E5000 for 1000-5000μl | |

| Universal Tips .1-10 μl | World Precision Instruments | 500192 | |

| Universal Tips 5-200 μl | World Precision Instruments | 500194 | |

| Universal Tips 500-5,000 μl | World Precision Instruments | 500198 | |

| Blade Vibroslice 100 | World Precision Instruments | BLADE | |

| DPX Mounting Medium | Electron Microscopy | 13510 | |

| 15 ml centrifuge tubes | Biologix Research Co. | 10-0501 | |

| Slide Boxes | Biologix Research Co. | 41-6100 | |

| Orbital Shaker | Madell Corporation | ZD-9556 | |

| weigh boats | Fisher Scientific | 02-202-100 | |

| 5 ml disposable pipettes | Fisher Scientific | 13-711-5AM | |

| Stereo Investigator Software | Micro Bright Field | Software application | |

| Name | Company | Catalog number | Comments |

| Reagents | |||

| Paraformaldehyde Granular | Fisher Scientific | 19210 | |

| NaCl | Fisher Scientific | S271-1 | |

| Sodium Phophate Monobasic | Fisher Scientific | S468-500 | |

| Sodium Phosphate Diphasic | Fisher Scientific | BP332-500 | |

| Hydrogen Peroxide | Fisher Scientific | H324-500 | |

| SafeClear II | Fisher Scientific | 23-044-192 | |

| Methanol | Fisher Scientific | A412-1 | |

| Normal Goat Serum | Vector | S-1000 | |

| Biotinylated Anti-Rabbit IgG (H+L) | Vector | BA-1000 | |

| ABC Kit Peroxidase Standard | Vector | PK-4000 | |

| Anti-cFos (Ab-5) Rabbit | EMD chem/Cal Biochem | PC38 | |

| Triton X 100 | SigmaAldrich | X-100 | |

| 3,3' diaminobenzidine tetra hydrochloride | SigmaAldrich | D5905 | |

| Sodium Hydroxide | SigmaAldrich | 5881 | |

| Primary TH anti body | EMD Millipore | AB152 | |

| Euthosol | Virbac AH |

参考文献

- Koob, G. F. Neural mechanisms of drug reinforcement. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 654, 171-191 (1992).

- Wise, R. A. Role of brain dopamine in food reward. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 361, 1149-1158 (2006).

- Salamone, J. D., Correa, M. The mysterious motivational functions of mesolimbic dopamine. Neuron. 76, 470-485 (2012).

- Horvitz, J. C., Choi, W. Y., Morvan, C., Eyny, Y., Balsam, P. D. A "good parent" function of dopamine: transient modulation of learning and performance during early stages of training. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1104, 270-288 (2007).

- Wickens, J. R., Horvitz, J. C., Costa, R. M., Killcross, S. Dopaminergic mechanisms in actions and habits. J. Neurosci. 27, 8181-8183 (2007).

- Bjorklund, A., Dunnett, S. B. Dopamine neuron systems in the brain: an update. Trends Neurosci. 30, 194-202 (2007).

- Swanson, L. W. The projections of the ventral tegmental area and adjacent regions: a combined fluorescent retrograde tracer and immunofluorescence study in the rat. Brain Res. Bull. 9, 321-353 (1982).

- Cacciapaglia, F., Wrightman, R. M., Careli, R. M. Rapid dopamine signaling differentially modulates distinct microcircuits within the nucleus accumbens during sucrose-directed behavior. J. Neurosci. 31, 13860-13869 (2011).

- Martinez-Hernandez, J., Lanuza, E., Martinez-Garcia, F. Selective dopaminergic lesions of the ventral tegmental area impair preference for sucrose but not for male sex pheromones in female mice. Eur. J. Neurosci. 24, 885-893 (2006).

- Bassareo, V., Di Chiara, G. Differential influence of associative and nonassociative learning mechanisms on the responsiveness of prefrontal and accumbal dopamine transmission to food stimuli in rats fed ad libitum. J. Neurosci. 17, 851-861 (1997).

- Bassareo, V., Di Chiara, G. Differential responsiveness of dopamine transmission to food-stimuli in nucleus accumbens shell/core compartments. Neurosci. 89, 637-641 (1999).

- Cheng, J., Feenstra, M. G. Individual differences in dopamine efflux in nucleus accumbens shell and core during instrumental conditioning. Learn. Mem. 13, 168-177 (2006).

- Genn, R. F., Ahn, S., Phillips, A. G. Attenuated dopamine efflux in the rat nucleus accumbens during successive negative contrast. Behav. Neurosci. 118, 869-873 (2004).

- Hajnal, A., Norgren, R. Accumbens dopamine mechanisms in sucrose intake. Brain Res. 904, 76-84 (2001).

- Hajnal, A., Smith, G. P., Norgren, R. Oral sucrose stimulation increases accumbens dopamine in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. 286, R31-R37 (2003).

- Bassareo, V., Di Chiara, G. Modulation of feeding-induced activation of mesolimbic dopamine transmission by appetitive stimuli and its relation to motivational state. Eur. J. Neurosci. 11, 4389-4397 (1999).

- Hajnal, A., Lenard, L. Feeding-related dopamine in the amygdala of freely moving rats. Neuroreport. 8, 2817-2820 (1997).

- Bassareo, V., De Luca, M. A., Di Chiara, G. Differential expression of motivational stimulus properties by dopamine in nucleus accumbens shell versus core and prefrontal cortex. J. Neurosci. 22, 4709-4719 (2002).

- Feenstra, M., Botterblom, M. Rapid sampling of extracellular dopamine in the rat prefrontal cortex during food consumption, handling, and exposure to novelty. Brain Res. 742, 17-24 (1996).

- Hernandez, L., Hoebel, B. G. Feeding can enhance dopamine turnover in the prefrontal cortex. Brain Res. Bull. 25, 975-979 (1990).

- Liang, N. C., Hajnal, A., Norgren, R. Sham feeding corn oil increases accumbens dopamine in the rat. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 291, R1236-R1239 (2006).

- Dunnett, S. B., Iversen, S. D. Regulatory impairments following selective kainic acid lesions of the neostriatum. Behav. Brain Res. 1, 497-506 (1980).

- Salamone, J. D., Zigmond, M. J., Stricker, E. M. Characterization of the impaired feeding behavior in rats given haloperidol or dopamine-depleting brain lesions. Neurosci. 39, 17-24 (1990).

- Kelley, A. E. Ventral striatal control of appetitive motivation: role in ingestive behavior and reward-related learning. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 27, 765-776 (2004).

- Kelley, A. E. Memory and addiction: shared neural circuitry and molecular mechanisms. Neuron. 44, 161-179 (2004).

- Kelley, A. E., Baldo, B. A., Pratt, W. E. A proposed hypothalamic-thalamic-striatal axis for the integration of energy balance, arousal and food reward. J. Comp. Neurol. 493, 72-85 (2005).

- Kelley, A. E., Baldo, B. A., Pratt, W. E., Will, M. J. Corticostriatal-hypothalamic circuitry and food motivation: integration of energy, action and reward. Physiol. Behav. 86, 773-795 (2005).

- Berendse, H. W., Galis-de-Graaf, Y., Groenewegen, H. J. Topographical organization and relationship with ventral striatal compartments of prefrontal corticostriatal projections in the rat. J. Comp. Neurol. 316, 314-347 (1992).

- Brog, J. S., Salyapongse, A., Deutch, A. Y., Zahm, D. S. The patterns of afferent innervation of the core and shell in the "accumbens" part of rat ventral striatum: immunohistochemical detection of retrogradely transported fluoro-gold. J. Comp. Neurol. 338, 255-278 (1993).

- McDonald, A. J. Organization of amygdaloid projections to the prefrontal cortex and associated stritum in the rat. Neurosci. 44, 1-14 (1991).

- McGeorge, A. J., Faull, R. L. The organization of the projection from the cerebral cortex to the striatum in the rat. Neurosci. 29, 503-537 (1989).

- Sesack, S. R., Deutch, A. Y., Roth, R. H., Bunney, B. S. Topographical organization of the efferent projections of the medial prefrontal cortex in the rat: an anterograde tract-tracing study with Phaseolus vulgaris leucoagglutinin. J. Comp. Neurol. 290, 213-242 (1989).

- Wright, C. I., Beijer, A. V., Groenewegen, H. J. Basal amygdaloid complex afferents to the rat nucleus accumbens are compartmentally organized. J. Neurosci. 16, 1877-1893 (1996).

- Wright, C. I., Groenewegen, H. J. Patterns of convergence and segregation in the medial nucleus accumbens of the rat: relationships of prefrontal cortical, midline thalamic and basal amygdaloid afferents. J. Comp. Neurol. 361, 383-403 (1995).

- Geary, N., Smith, G. P. Pimozide decreases the positive reinforcing effect of sham fed sucrose in the rat. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 22, 787-790 (1985).

- Muscat, R., Willner, P. Effects of selective dopamine receptor antagonists on sucrose consumption and preference. Psychopharmacol. 99, 98-102 (1989).

- Schneider, L. H., Gibbs, J., Smith, G. P. D-2 selective receptor antagonists suppress sucrose sham feeding in the rat. Brain Res. Bull. 17, 605-611 (1986).

- Baker, R. W., Osman, J., Bodnar, R. J. Differential actions of dopamine receptor antagonism in rats upon food intake elicited by mercaptoacetate or exposure to a palatable high-fat diet. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 69, 201-208 (2001).

- Rao, R. E., Wojnicki, F. H., Coupland, J., Ghosh, S., Corwin, R. L. Baclofen, raclopride and naltrexone differentially reduce solid fat emulsion intake under limited access conditions. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 89, 581-590 (2008).

- Weatherford, S. C., Smith, G. P., Melville, L. D. D-1 and D-2 receptor antagonists decrease corn oil sham feeding in rats. Physiol. Behav. 44, 569-572 (1988).

- Azzara, A. V., Bodnar, R. J., Delamater, A. R., Sclafani, A. D1 but not D2 dopamine receptor antagonism blocks the acquisition of a flavor preference conditioned by intragastric carbohydrate infusions. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 68, 709-720 (2001).

- Baker, R. M., Shah, M. J., Sclafani, A., Bodnar, R. J. Dopamine D1 and D2 antagonists reduce the acquisition and expression of flavor-preferences conditioned by fructose in rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 75, 55-65 (2003).

- Dela Cruz, J. A., Coke, T., Icaza-Cukali, D., Khalifa, N., Bodnar, R. J. Roles of NMDA and dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in the acquisition and expression of flavor preferences conditioned by oral glucose in rats. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 114, 223-230 (2014).

- Dela Cruz, J. A., et al. Roles of dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in the acquisition and expression of fat-conditioned flavor preferences in rats. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 97, 332-337 (2012).

- Yu, W. Z., Silva, R. M., Sclafani, A., Delamater, A. R., Bodnar, R. J. Pharmacology of flavor preference conditioning in sham-feeding rats: effects of dopamine receptor antagonists. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 65, 635-647 (2000).

- Yu, W. Z., Silva, R. M., Sclafani, A., Delamater, A. R., Bodnar, R. J. Role of D(1) and D(2) dopamine receptors in the acquisition and expression of flavor-preference conditioning in sham-feeding rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav. 67 (1), 537-544 (2000).

- Touzani, K., Bodnar, R. J., Sclafani, A. Activation of dopamine D1-like receptors in nucleus accumbens is critical for the acquisition, but not the expression, of nutrient-conditioned flavor preferences in rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 27, 1525-1533 (2008).

- Touzani, K., Bodnar, R. J., Sclafani, A. Dopamine D1-like receptor antagonism in amygdala impairs the acquisition of glucose-conditioned flavor preference in rats. Eur. J. Neurosci. 30, 289-298 (2009).

- Touzani, K., Bodnar, R. J., Sclafani, A. Acquisition of glucose-conditioned flavor preference requires the activation of dopamine D1-like receptors within the medial prefrontal cortex in rats. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 94, 214-219 (2010).

- Malkusz, D. C., et al. Dopamine signaling in the medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala is required for the acquisition of fructose-conditioned flavor preferences in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 233, 500-507 (2012).

- Bernal, S. Y., et al. Role of dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in the nucleus accumbens shell on the acquisition and expression of fructose-conditioned flavor-flavor preferences in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 190, 59-66 (2008).

- Bernal, S. Y., et al. Role of amygdala dopamine D1 and D2 receptors in the acquisition and expression of fructose-conditioned flavor preferences in rats. Behav. Brain Res. 205, 183-190 (2009).

- Dragunow, M., Faull, R. The use of c-fos as a metabolic marker in neuronal pathway tracing. J. Neurosci. Methods. 29, 261-265 (1989).

- VanElzakker, M., Fevurly, R. D., Breindel, T., Spencer, R. L. Environmental novelty is associated with a selective increase in Fos expression in the output elements of the hippocampal formation and the perirhinal cortex. Learn. Mem. 15, 899-908 (2008).

- Norgren, R., Hajnal, A., Mungarndee, S. S. Gustatory reward and the nucleus accumbens. Physiol. Behav. 89, 531-535 (2006).

- Park, T. H., Carr, K. D. Neuroanatomical patterns of fos-like immunoreactivity induced by a palatable meal and meal-paired environment in saline- and naltrexone-treated rats. Brain Res. 805, 169-180 (1998).

- Zhao, X. L., Yan, J. Q., Chen, K., Yang, X. J., Li, J. R., Zhang, Y. Glutaminergic neurons expressing c-Fos in the brainstem and amygdala participate in signal transmission and integration of sweet taste. Nan.Fang Yi.Ke.Da.Xue.Xue.Bao. 31, 1138-1142 (2011).

- Mungarndee, S. S., Lundy, R. F., Norgren, R. Expression of Fos during sham sucrose intake in rats with central gustatory lesions. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 295, R751-R763 (2008).

- Otsubo, H., Kondoh, T., Shibata, M., Torii, K., Ueta, Y. Induction of Fos expression in the rat forebrain after intragastric administration of monosodium L-glutamate, glucose and NaCl. Neurosci. 196, 97-103 (2011).

- Yamamoto, T., Sako, N., Sakai, N., Iwafune, A. Gustatory and visceral inputs to the amygdala of the rat: conditioned taste aversion and induction of c-fos-like immunoreactivity. Neurosci. Lett. 226, 127-130 (1997).

- Mitra, A., Lenglos, C., Martin, J., Mbende, N., Gagne, A., Timofeeva, E. Sucrose modifies c-fos mRNA expression in the brain of rats maintained on feeding schedules. Neurosci. 192, 459-474 (2011).

- Pecoraro, N., Dallman, M. F. c-Fos after incentive shifts: expectancy, incredulity, and recovery. Behav. Neurosci. 119, 366-387 (2005).

- Hamlin, A. S., Blatchford, K. E., McNally, G. P. Renewal of an extinguished instrumental response: Neural correlates and the role of D1 dopamine receptors. Neurosci. 143, 25-38 (2006).

- Kerfoot, E. C., Agarwal, I., Lee, H. J., Holland, P. C. Control of appetitive and aversive taste-reactivity responses by an auditory conditioned stimulus in a devaluation task: A FOS and behavioral analysis. Learn. Mem. 14, 581-589 (2007).

- Zhang, M., Kelley, A. E. Enhanced intake of high-fat food following striatal mu-opioid stimulation: microinjection mapping and fos expression. Neurosci. 99, 267-277 (2000).

- Teegarden, S. L., Scott, A. N., Bale, T. L. Early life exposure to a high fat diet promotes long-term changes in dietary preferences and central reward signaling. Neurosci. 162, 924-932 (2009).

- Del Rio, D., et al. Involvement of the dorsomedial prefrontal cortex in high-fat food conditioning in adolescent mice. Behav. Brain Res. 283, 227-232 (2015).

- Knapska, E., Radwanska, K., Werka, T., Kaczmarek, L. Functional internal complexity of amygdala: focus on gene activity mapping after behavioral training and drugs of abuse. Physiol. Rev. 87, 1113-1173 (2007).

- Dela Cruz, J. A. D., et al. c-Fos induction in mesotelencephalic dopamine pathway projection targets and dorsal striatum following oral intake of sugars and fats in rats. Brain Res. Bull. 111, 9-19 (2015).

- Paxinos, G., Watson, C. . The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. , (2006).

- Ranaldi, R., et al. The effects of VTA NMDA receptor antagonism on reward-related learning and associated c-fos expression in forebrain. Behav. Brain Res. 216, 424-432 (2011).

转载和许可

请求许可使用此 JoVE 文章的文本或图形

请求许可探索更多文章

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

版权所属 © 2025 MyJoVE 公司版权所有,本公司不涉及任何医疗业务和医疗服务。