A subscription to JoVE is required to view this content. Sign in or start your free trial.

Method Article

הערכה של תפקוד העצבי באמצעות גירוי עצבי חשמלי Percutaneous

In This Article

Summary

We present a protocol to assess changes in neuromuscular function. Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation is a non-invasive method that evokes muscular responses. Electrophysiological and mechanical properties of these responses permit the evaluation of neuromuscular function from brain to muscle (supra-spinal, spinal and peripheral levels).

Abstract

Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation is a non-invasive method commonly used to evaluate neuromuscular function from brain to muscle (supra-spinal, spinal and peripheral levels). The present protocol describes how this method can be used to stimulate the posterior tibial nerve that activates plantar flexor muscles. Percutaneous electrical nerve stimulation consists of inducing an electrical stimulus to a motor nerve to evoke a muscular response. Direct (M-wave) and/or indirect (H-reflex) electrophysiological responses can be recorded at rest using surface electromyography. Mechanical (twitch torque) responses can be quantified with a force/torque ergometer. M-wave and twitch torque reflect neuromuscular transmission and excitation-contraction coupling, whereas H-reflex provides an index of spinal excitability. EMG activity and mechanical (superimposed twitch) responses can also be recorded during maximal voluntary contractions to evaluate voluntary activation level. Percutaneous nerve stimulation provides an assessment of neuromuscular function in humans, and is highly beneficial especially for studies evaluating neuromuscular plasticity following acute (fatigue) or chronic (training/detraining) exercise.

Introduction

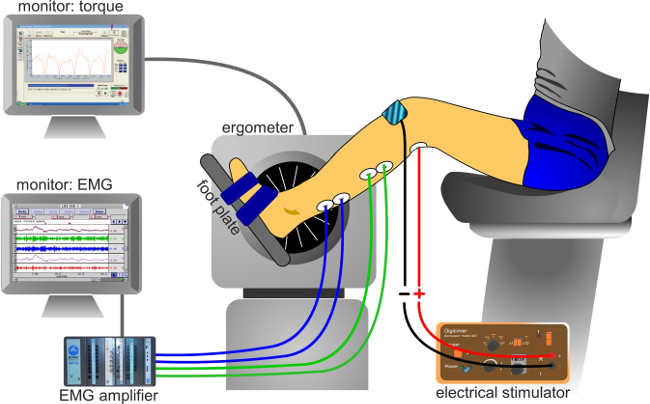

גירוי עצבי חשמלי מלעורית הוא בשימוש נרחב כדי להעריך את התפקוד עצבית-שרירית 1. העיקרון הבסיסי מורכב מגרימת גירוי חשמלי לעצב מוטורי היקפי לעורר התכווצות שרירים. (מדידת מומנט) מכאנית ואלקטרו תגובות (פעילות electromyographic) נרשמות בו זמנית. מומנט, נרשם במפרק נחשב, נבחנים באמצעות ergometer. אות electromyographic (EMG) נרשמה באמצעות אלקטרודות משטח הודגמה לייצג את הפעילות של השריר 2. שיטה לא פולשנית זה אינה כואבת ויותר בקלות ליישם מאשר הקלטות תוך שרירית. שניהם יכולים לשמש אלקטרודות monopolar ודו קוטביות. תצורת אלקטרודה monopolar הוכחה להיות רגיש יותר לשינויים בפעילות שרירים 3, אשר יכול להיות שימושי עבור שרירים קטנים. עם זאת, אלקטרודות דו קוטביות הוכחו להיות יעיל יותר בשיפור R אות לרעש4 atio והם נפוצים ביותר כשיטת הקלטה וכימות פעילות יחידת מנוע. המתודולוגיה שתוארה להלן תתמקד בהקלטות דו קוטביות. פעילות EMG היא אינדיקטור של היעילות והיושרה של המערכת העצבית-שרירית. השימוש בגירוי עצב מלעורית מציע תובנות נוספות פונקציה עצבית-שרירית, שינויים כלומר ברמת שרירים, עמוד השדרה, או על-השדרה (איור 1).

איור 1:. סקירה של המדידות העצבית-שרירית STIM: גירוי עצב. EMG: Electromyography. VAL: רמת הפעלה מרצון. RMS: שורש ממוצע כיכר. מקסימום M: משרעת M-גל מקסימאלי.

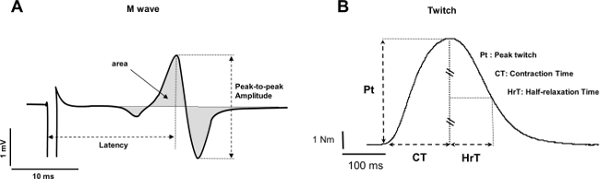

במנוחה, פוטנציאל פעולת השרירים מתחם, המכונה גם M-גל, הוא התגובה קצרת חביון נצפתה לאחר artefact הגירוי, ומייצג את מסת שריר להתרגש על ידי Activ הישיר ני של אקסונים מוטוריים המובילים לשריר (איור 2, מספר 3). משרעת M-גל מגבירה בעוצמה עד שמגיע לרמה של הערך המקסימאלי שלה. תגובה זו, המכונה M מקסימום, מייצגת את סיכום סינכרוני של כל היחידות המוטוריות ו / או פוטנציאל פעולת סיב שריר נרשמו מתחת לאלקטרודות EMG המשטח 5. האבולוציה של האזור משרעת או גל שיא-לשיא משמשת לזיהוי שינויים של העברת עצבית-שרירית 6. שינויים בתגובות מכאניות הקשורים M-הגל, כלומר מומנט / כוח עווית שיא, יכולים להיות בגלל שינויים ברגישות שרירים ו / או בסיבי השריר 7. העמותה של משרעת מקסימום M ומשרעת עווית שיא מומנט (יחס / M Pt) מספקת מדד של יעילות אלקטרו של השריר 8, כלומר תגובה מכאנית לפקודת מנוע חשמלית נתון.

52,974 / 52974fig2.jpg "/>

איור 2:. מוטורי ומסלולים רפלקסיבית מופעלים על ידי גירוי עצב גירוי חשמלי של (מוטורי / חושי) עצב מעורב (STIM) גורם שלילת קוטביות של האקסון מוטורי והן ירי מביא Ia. שלילת קוטביות של Ia afferents כיוון חוט השדרה מפעיל motoneuron אלפא, אשר בתורו מעורר תגובת H-רפלקס (מסלול 1 + 2 + 3). בהתאם לעוצמת הגירוי, שלילת קוטביות האקסון מוטורי מעוררת תגובה ישירה שרירים: M-גל (מסלול 3). בעצימות M-גל מקסימאלי, נוכחית antidromic גם נוצר (3 ') ומתנגש עם מטח רפלקס (2). התנגשות זו באופן חלקי או לחלוטין מבטלת את תגובת H-רפלקס.

H-רפלקס הוא תגובת אלקטרו שימשה להערכת שינויים בסינפסה motoneuron IA-α 9. פרמטר זה ניתן להעריך במנוחה או במהלך צירים מרצון. H-רפלקס מייצג גרסה של רפלקס המתיחה (איור 2, נוmber 1-3). H-רפלקס מפעיל יחידות מוטוריות גויסו על ידי monosynaptically מסלולים מביא Ia 10,11, ויכול להיות נתונה להשפעות היקפית ומרכזיות 12. השיטה לעורר H-רפלקס ידוע לי אמינות התוך נושא גבוהה להעריך רגישות בעמוד השדרה ב13,14 מנוחה ובהתכווצויות איזומטרי 15.

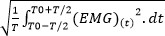

במהלך התכווצות רצון, בסדר הגודל של הכונן העצבי מרצון ניתן להעריך באמצעות המשרעת של אות EMG, בדרך כלל לכמת באמצעות כיכר Mean השורש (RMS). RMS EMG הוא נפוץ באמצעות כימות רמת העירור של המערכה התנועה במהלך התכווצות רצון (איור 1). בגלל שונות התוך והבין-נושא 16, RMS EMG יש מנורמל באמצעות EMG שנרשם במהלך התכווצות רצון מקסימלי שריר ספציפי (RMS EMGmax). בנוסף, בגלל שינויים באות EMG עשויים bדואר עקב שינויים ברמה היקפית, נורמליזציה באמצעות פרמטר היקפי כגון M-גל נדרש להעריך את המרכיב המרכזי רק של אות EMG. ניתן לעשות זאת על ידי חלוקת EMG RMS על ידי משרעת המקסימלי או Mmax RMS של M-הגל. נורמליזציה באמצעות RMS Mmax (כלומר RMS EMG / RMS Mmax) הוא השיטה המועדפת כפי שהוא לוקח בחשבון את השינוי האפשרי של משך M-גל 17.

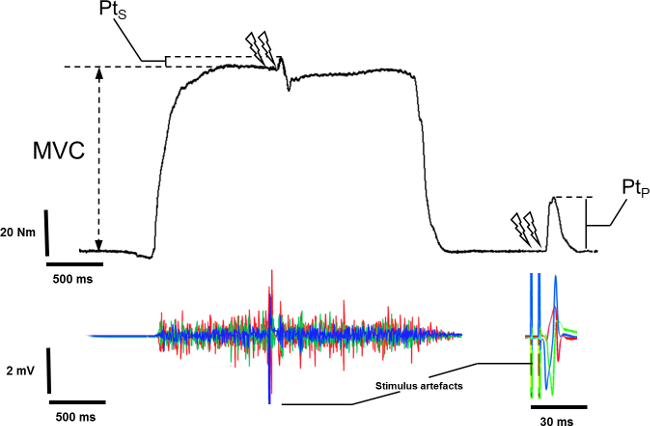

יכולות גם להיות מוערכות פקודות מוטוריות על ידי חישוב רמת התנדבות ההפעלה (VAL). שיטה זו משתמשת בטכניקת אינטרפולציה עווית 18 על ידי superimposing גירוי חשמלי בעוצמה מקסימלי M במהלך התכווצות רצון מקסימלי. במיוחד המומנט הנגרם על ידי גירוי העצב הוא בהשוואה לעווית שליטה המיוצרת על ידי גירוי עצב זהה בשריר potentiated רגוע 19. כדי להעריך VAL המקסימאלי, interpo העווית המקוריתטכניקה שתוארה על ידי ויסות ריטון 18 כרוך גירוי יחיד אינטרפולציה על התכווצות בהתנדבות. לאחרונה, השימוש בגירוי לזווג הפך פופולרי יותר, כי מרווחי המומנט עוררו גדולים יותר, זוהה בקלות רבה יותר, ופחות משתנה בהשוואה לתגובות גירוי יחידה 20. VAL מספק מדד של היכולת של מערכת העצבים המרכזית להפעיל מקסימאלי שרירים עובדים 21. נכון לעכשיו, VAL הוערך באמצעות טכניקת אינטרפולציה העווית היא השיטה יקרה ביותר של הערכת הרמה של הפעלת שרירים 22. יתר על כן, מומנט השיא הוערך באמצעות ergometer הוא פרמטר בדיקת החוזק ביותר למד כראוי ישים שימוש במחקר ובהגדרות קליניות 23.

גירוי עצבי חשמלי ניתן להשתמש במגוון רחב של קבוצות שרירים (מכופפי מרפק למשל, מכופפי שורש כף יד, פושטי הברך, מכופפי plantar). עם זאת, נגישות עצב גורמתטכניקה קשה בכמה קבוצות שרירים. השרירים הכופפים plantar, במיוחד היד אחורית surae (soleus וgastrocnemii) שרירים, לעתים קרובות נחקרו בספרות 24. ואכן, אלה שרירים מעורבים בתנועה, המצדיקים את העניין המיוחד שלהם. המרחק בין אתר גירוי ואלקטרודות הקלטה מאפשר זיהוי של הגלים עוררו השונים של שרירי surae היד האחורית. החלק השטחי של עצב הטיביאלי האחורי בגומץ popliteal והמספר הגדול של צירים שיהיו קל יותר לרשום תגובות רפלקס לעומת שרירים אחרים 24. מסיבות אלה, המתודולוגיה רפלקס מוצגת כיום מתמקדת בקבוצת surae היד האחורית של שרירים (soleus והגסטרוקנמיוס). המטרה של פרוטוקול זה היא אפוא לתאר טכניקת גירוי עצב מלעורית לחקור פונקציה עצבית-שרירית בsurae היד האחורית.

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Protocol

הפרוצדורות התוו קיבלו אישור אתי מוסדי והנן בהתאם להצהרת הלסינקי. הנתונים נאספו ממשתתף נציג שהיה מודע לנהלים ונתנו בכתב ההסכמה מהדעת שלו.

1. כלי הכנה

- נקה את העור במיקום האלקטרודה על ידי גילוח, ולהסיר את הלכלוך עם אלכוהול כדי להשיג עכבה נמוכה (<5 ק"ג-אוהם).

- מניחים שתי אלקטרודות AgCl פני השטח (בקוטר של 10 מ"מ הקלטה) ב2/3 מהקו בין condylis המדיאלי של עצם הירך לmalleolus המדיאלי לשריר הסוליה; על הבליטה הבולטת של השריר להגסטרוקנמיוס המדיאלי; ב1/3 מהמרחק לאורך קו בין ראש שוקית והעקב להגסטרוקנמיוס הרוחב; וב1/3 מהמרחק לאורך קו בין קצה שוקית ואת קצה המדיאלי malleolus לשריר הקדמי tibialis, עם interelectroמרחק דה (מרכז למרכז) של 2 סנטימטר, על פי המלצות SENIAM 30.

הערה: אלקטרודות שריר הסוליה צריכה להיות ממוקמות מתחת להחדרה הדיסטלי של שרירי gastrocnemii כדי להבטיח שהם לא הקלטת פעילות מראשי שרירי gastrocnemii (הצטלבות). - מניחים אלקטרודה התייחסות במיקום מרכזי באותו הרגל (בין הגירוי והקלטת אתרים).

- התאם את הגובה והעומק של הכיסא כדי להשיג זווית קרסול של 90 מעלות (0 ° = כיפוף plantar מלא), כך שsoleus והשרירים gastrocnemii לא נמתחים וH-רפלקס לא שינה 11,12.

- הגדר את זווית הברך ב 90 מעלות (0 ° = הארכת הברך מלאה) בשל אופי biarticular של שרירי gastrocnemii. עם זאת, זווית הקרסול האופטימלית לבצע מומנט מרצון מקסימאלי של מכופפי plantar היא 70-80 מעלות (0 ° = כיפוף plantar מלא) 26. לפיכך, זווית קרסול תהיה תלויה בסעיףמטר של עניין (אלקטרו לעומת הקלטות מכאניות).

הערה: לא משנה את הזווית הראשונית נבחרה, הוא חייב להישאר קבוע לאורך כל הניסוי כדי לתקן רגישות עצבית-שרירית 11,12,27,28. - שים לב במיוחד כאשר ניטור היציבה של הנבדקים במהלך הבדיקה כדי לשמור על השפעות cortico-שיווי המשקל קבועים על הרגישות של בריכת מנוע 29.

- הגדר את זווית הברך ב 90 מעלות (0 ° = הארכת הברך מלאה) בשל אופי biarticular של שרירי gastrocnemii. עם זאת, זווית הקרסול האופטימלית לבצע מומנט מרצון מקסימאלי של מכופפי plantar היא 70-80 מעלות (0 ° = כיפוף plantar מלא) 26. לפיכך, זווית קרסול תהיה תלויה בסעיףמטר של עניין (אלקטרו לעומת הקלטות מכאניות).

- בתוקף לקשור את הקרסול לergometer, עם הציר האנטומי של המפרק (malleolus החיצוני) מיושר עם ציר סיבוב של ergometer 25.

- יש להן לוחץ על הנושא אדן המצורף לergometer להקליט מומנט מכופף plantar. שמור נייח הרגל לאורך הניסוי, כך שיכולים להיות מזוהים שינויים קטנים במומנט.

- הערה: בנסיבות מסוימות, את העקב עשוי להרים מעט מצלחת הכוח אם כף הרגל והקרסול אינן מובטחות, אשר עשוי leמודעה להעברה חלקית של המומנט נגד הצלחת. איור 3 מציגה תיאור של הגדרת הניסוי.

איור 3:. התקנה ניסיונית הגדרת ניסוי קלאסית להקליט אותות (EMG) והמומנט electromyographic.

- חבר את האלקטרודות למגבר עם כבלים.

- הגדר את קצב הדגימה למדידות מומנט וEMG ל2-5 קילוהרץ. רשום את אות EMG באמצעות מערך גיור אנלוגי לדיגיטלי (AD). האות מוצגת על צג עם נתוני מערכת רכישה, אשר באופן מיידי נותנת ערכים של מספר פרמטרים (למשל מקסימאלי ערך, משרעת שיא-לשיא, משך). הספקטרום של אות EMG יכול לנוע בין 5 הרץ ו -2 תדרי kHz, אבל הוא הכיל בעיקר בין 10 הרץ וkHz 1 31. לפיכך, תדר דגימה חייב להיות גבוה מספיק כדי לשמור על צורת אות during הקלטת EMG. להגביר ולסנן אותות EMG (רווח = 500-100) באמצעות תדר רוחב פס בין 10 הרץ ו1 kHz 8,21,32.

- מניחים את האנודה לגירוי החשמלי על גיד הפיקה.

- קבע את האתר הטוב ביותר של גירוי עצב הטיביאלי האחורי כדי להשיג רפלקס H soleus אופטימלי לעצמת נתונה, באמצעות אלקטרודה קתודת כדור יד שנערכה בגומץ popliteal. בדוק כמה אתרי גירוי עם אלקטרודה קתודת הכדור עד לערך מקסימאלי של רפלקס H.

- פעילות EMG הקדמית tibialis רשומה על מנת להבטיח כי עצב peroneal המשותף אינו מופעל, כדי למנוע השפעה מהיריב Ia afferents 12. הגדר את הרוחב הדופק ב1 msec לספק הפעלה אופטימלית של סיבי עצבים, במיוחד סיבים מביא 10.

- הנח קתודת AgCl דביקה במיקומו של אתר הגירוי כדי להבטיח מצב גירוי מתמיד (למשל לחץ, אוריינטני).

הערה: כל הפרמטרים האלה (מיקום נושא, מיקום האלקטרודה ואתר גירוי) לא תשתנה להערכה של מדידות אלקטרו השונות. רק עוצמת הגירוי והמצב (שאר לעומת התכווצות) להשתנות.

2. נהלי בדיקה במנוחה

- להורות לנושא להישאר רגוע ולשמור / שריריו במנוחה.

- התאם את עוצמת הגירוי להשיג soleus המקסימאלי H-רפלקס משרעת (H מקסימום; טווח רגיל: 20-50 אמפר). M-גל של שריר הסוליה ניתן להבחין בעוצמת מקסימום H.

הערה: מדידות חוזרות (לדוגמא לפני ואחרי פרוטוקול מעייף), עוצמת האופטימלית כדי להשיג תגובת מקסימום H עשוי להשתנות במהלך הפגישה. כשמירה על עוצמת קבועה יכול להוביל להערכה נמוכה מדי של משרעת מקסימום H, מומלץ שהנסיין שב ומנתחת מקסימום H באופן קבועעוצמה 33. - להקליט מינימום של תגובות H-רפלקס 3 soleus בעוצמה זו עם מרווח מינימאלי של 3 שניות, כדי למנוע דיכאון לאחר ההפעלה 34.

הערה: למרות שההקלטה כמה תגובות מתאימה יותר בשל הרגישות המיוחדת של H-רפלקס, גירוי בודד עשוי להיות מספיק בנסיבות מסוימות, לדוגמא כאשר מנסים למנוע את ההשפעות של התאוששות מהירה (למשל בפרוטוקול מעייף). - להגביר את עוצמת הגירוי להשיג משרעת M-גל soleus המקסימאלי (M מקסימום; טווח רגיל: 40-100 אמפר). בדרך כלל, להגדיר את התוספת בעוצמת גירוי ב2-4 mA, עם מרווח של 8-10 שניות בין שני 12,35 גירויים. הוא הגיעה בעוצמה הרצויה כאשר M המקסימום מתקבל, ואין תגובת H-רפלקס ניתן לצפות.

- הגדר את עוצמת הסופית 120-150% מעוצמת גירוי מקסימלי M כדי להבטיח כי M-הגל משיג רמה של הערך המקסימאלי שלה. התעצם זהטאי נקרא עוצמת supramaximal בהוראות שלהלן.

- שמור עוצמת גירוי מתמדת להקלטות M-גל soleus לאורך כל הפגישה.

- שיא M-גלי 3 soleus ו -3 מגבילי העווית קשורים בעוצמה זו.

3. נהלי בדיקה במהלך התכווצות רצון

- כחימום, לשאול את הנושא כדי לבצע התכווצויות submaximal 10 קצרות ולא לעייף את השרירים המכופפים plantar, עם שאר כמה שניות בין כל אחד מהצירים. בסופו של החימום, לנוח 1 דקות מינימום כדי למנוע תופעות מתישות 11.

- פעילות EMG surae היד האחורית ברציפות שיא. soleus הקלטה והשרירים gastrocnemii מאפשר הניתוח של ההתנהגות של טיפולוגיות שרירים שונות לאתר גירוי יחיד 24.

- הדריכו את הנושא כדי לבצע כיווץ איזומטרי מקסימאלי מרצון (MVC) של מכופפי plantar. הנושא צריך לדחוף קשה כמו possible נגד ergometer על ידי כיווץ השרירים הכופפים plantar. לתת משוב חזותי לנושא במהלך המאמץ, ועידוד מילולי סטנדרטי 19. MVC הוא הגיע כאשר רמה שנצפתה.

- לספק גירוי לזווג (100 תדר Hz) בעוצמה supramaximal במהלך הרמה של MVC (כפיל גבי), ועוד גירוי לזווג כאשר השריר הוא רגוע לחלוטין מייד לאחר ההתכווצות (כפיל potentiated) כדי להעריך את רמת הפעלה מרצון. לספק גירוי לזווג זה דרך מכשיר ספציפי (למשל Digitimer D185 MultiPulse ממריץ) או באמצעות תכנית גירוי קשורה לממריץ דופק יחיד.

- הדריכו את הנושא כדי לבצע MVC שני של מכופף plantar עם שאר דקות לפחות 1 בין כל משפט 11. אם מומנט השיא מהמשפט השני הוא לא בתוך 5% מהראשונים, יש לבצע ניסויים נוספים 36. המומנט הגדול ביותר שהושג על ידיהנושא נלקח כמומנט MVC.

ניתוח נתונים 4.

- ניתוח נתונים במנוחה

- בחר חלון זמן הכולל את תגובת EMG הקשורים לעווית במנוחה (H-גל או M-גל).

- מדוד את המשך משרעת שיא-לשיא, שיא-לשיא, ו / או השטח של הגלים (איור 4 א). אם משרעת אינה מסופקת ישירות על ידי התוכנה, להפחית את המינימום לערכים המרביים.

- למשך, למדוד את מסגרת הזמן מתחיל מהפסגה המקסימלי וכלה לשיא המינימלי. לאזור, לחשב נפרד מאות EMG החל מתחילתו של הגל וכלה בסופו של הגל.

הערה: משרעת שיא-לשיא יכול לשקף: 1) העברת עצבית-שרירית, 2) משרעת פעולת יחידת מנוע פוטנציאלי ו / או 3) פיזור זמני של פעולת יחידת מנוע פוטנציאל 37. משך M-גל משקף התפשטות עצבית-שרירית 37.

- למשך, למדוד את מסגרת הזמן מתחיל מהפסגה המקסימלי וכלה לשיא המינימלי. לאזור, לחשב נפרד מאות EMG החל מתחילתו של הגל וכלה בסופו של הגל.

- לניסויים מרובים, לחשב את הממוצע של הגלים. אם הממוצע לא יכול להיות מסופק ישירות על ידי תוכנה, תוכנת גיליון אלקטרוני שימוש (למשל פונקצית הנוסחה בתכנית גיליון אלקטרוני) כדי לחשב ערך זה מכמה ניסויים (לפחות 3).

- בחר את עווית המנוחה.

- מדוד את מומנט השיא הקשורים לעווית המנוחה (איור 4).

- לניסויים מרובים, לחשב את מומנט השיא הממוצע של פרכוסי מנוחה. אם הממוצע לא יכול להיות מסופק ישירות על ידי תוכנה, תוכנת גיליון אלקטרוני שימוש (למשל פונקצית הנוסחה בתכנית גיליון אלקטרוני) כדי לחשב ערך זה מכמה ניסויים (לפחות 3).

- חזור על נהלים אלה שתוארו בנקודה 4.1.2 לפרמטרים האחרים הרצויים (זמן התכווצות או זמן מחצית-הרפיה). הניתוח של פרמטרים עווית מספק אינדיקציות ליעילות צימוד עירור-התכווצות 17. בפרט, חוזהזמן יון מספק מדד של קינטיקה התכווצות 8, שיכול לסמוך על קבוצת השרירים נבחר 38.

- לחשב את היחס בין מומנט השיא והסכום של M-גלים באמצעות תוכנת גיליון אלקטרוני (למשל Excel), לכמת את יעילות אלקטרו (t P / M). כתגובות מכאניות עוררו על ידי גירוי עצב הטיביאלי אחורי מתאימות להפעלה של 39 היד האחורית surae בכללותו, אמפליטודות של soleus וgastrocnemii M-גלים חייבת להיות סיכמה.

איור 4: הסבר על תגובות אלקטרו מכניות מדידה () של משרעת שיא-לשיא (mV), מיסות (MS) ואזור (mV.ms) של M-גל אופייני.. מדידה (ב ') של מומנט עווית שיא (ננומטר), זמן התכווצות (MS) וזמן מחצית-הרפיה (אלפיות שני) של עווית. לחץ כאן כדי לצפות בגרסה גדולה יותר של דמות זו.

- ניתוח נתונים בהתכווצות

- בחר חלון של פעילות EMG soleus 500 זמן msec ברמה של מומנט MVC כוללים מומנט השיא אך לא כולל את הזמן בין artefact הגירוי ותום התקופה השקטה של EMG. תקופה השקטה מתאימה לדיכוי של פעילות EMG מרצון המתמשכת בעקבות גירוי.

- אם השורש מתכוון מרובע (RMS) לא מסופק ישירות על ידי התוכנה, לחשב את RMS לכמת פעילות EMG באמצעות הנוסחא 40 הבאה: RMS EMG

- למדוד או לחשב את RMS של מקס M במנוחה על משך הגל.

- לחשב את יחס RMS EMG / RMS Mmax באמצעות תוכנת גיליון אלקטרוני.ערך EMG RMS וערך RMS Mmax צריכים להיות נבחרו מאותו השריר.

- מדוד את מומנט השיא המקסימאלי של MVC מנקודת ההתחלה של מומנט במנוחה לערך המקסימאלי של MVC לא כולל המומנט גבי נגרם על ידי גירוי כפיל (איור 5).

- מדוד את המומנט גבי נגרם על ידי גירוי כפיל בMVC, מערך המומנט מרצון בתחילת הגירוי לשיא של התגובה שמעוררת ב( איור 5).

- בחר את כפיל potentiated.

- מדוד את מומנט השיא הקשורים לכפיל potentiated.

- לחשב את רמת התנדבות ההפעלה (VAL) באמצעות הנוסחא 40 הבאה:

ומדידה של גבי: איור 5potentiated כפיל באות מכאנית. כדי להקליט המומנט גבי השיא (נק '), כפיל גירוי עורר ברמה של כיווץ איזומטרי מקסימאלי מרצון (MVC). כדי להקליט מומנט שיא potentiated (Pt P), כפיל גירוי עורר במנוחה ולאחר קיזוז MVC.

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

תוצאות

עוצמת גירוי הגדלת מובילה להתפתחות של אמפליטודות תגובה בין H- וM-גלים שונה. במנוחה, H-רפלקס מגיע לערך מרבי לפני שנעדר לחלוטין מאות EMG, ואילו גל M בהדרגה מגביר עד שמגיע לרמה בעוצמה מקסימלי (ראה תרשים 4 לתיאור גרפי של M-הגל ואיור 6 לאבולוציה של M-גלים וH-רפלקס ...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Discussion

גירוי עצב מלעורית מאפשר כימות של מספר רב של מאפיינים של המערכת העצבית-שרירית לא רק להבין את השליטה הבסיסית של תפקוד נוירו-מוטורי בבני אדם בריאים, אלא גם להיות מסוגל לנתח עיבודים אקוטיים או כרוניים באמצעות עייפות או הכשרת 17. זה מועיל מאוד במיוחד עבור פרוטוקולים ?...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgements.

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Biodex dynamometer | Biodex Medical System Inc., New York, USA | www.biodex.com | |

| MP150 Data Acquisition System | Biopac Systems Inc., Goleta, USA | ||

| Acknowledge 4.1.0 software | Biopac Systems Inc., Goleta, USA | www.biopac.com | |

| DS7A constant current high voltage stimulator | Digitimer, Hertfordshire, UK | www.digitimer.com | |

| Silver chloride surface electrodes | Control Graphique Medical, Brie-Comte-Robert, France | ||

| Computer | |||

| 1 Cable for connecting the Biodex to the MP150 | |||

| 1 Cable for connecting the Digitimer to the MP150 | |||

| 1 Cable for connecting the MP150 to the computer |

References

- Desmedt, J. E., Hainaut, K. Kinetics of myofilament activation in potentiated contraction staircase phenomenon in human skeletal muscle. Nature. 217 (5128), 529-532 (1968).

- Bouisset, S., Maton, B. Quantitative relationship between surface EMG and intramuscular electromyographic activity in voluntary movement. American Journal of Physical Medicine. 51 (6), 285-295 (1972).

- Gabriel, D. A. Effects of monopolar and bipolar electrode configurations on surface EMG spike analysis. Medical Engineering and Physics. 33 (9), 1079-1085 (2011).

- Merletti, R., Rainoldi, A., Farina, D. Surface electromyography for noninvasive characterization of muscle. Exercise and Sport Sciences Reviews. 29 (1), 20-25 (2001).

- Lepers, R. Aetiology and time course of neuromuscular fatigue during prolonged cycling exercises. Science, & Motricité. 52, 83-107 (2004).

- Baudry, S., Klass, M., Pasquet, B., Duchateau, J. Age related fatigability of the ankle dorsiflexor muscles during concentric and eccentric contractions. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 100 (5), 515-525 (2007).

- Place, N., Yamada, T., Bruton, J. D., Westerblad, H. Muscle fatigue From observations in humans to underlying mechanisms studied in intact single muscle fibres. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 110 (1), 1-15 (2010).

- Scaglioni, G., Narici, M. V., Maffiuletti, N. A., Pensini, M., Martin, A. Effect of ageing on the electrical and mechanical properties of human soleus motor units activated by the H reflex and M wave. The Journal of Physiology. 548 (Pt. 2), 649-661 (2003).

- Schieppati, M. The Hoffmann reflex a means of assessing spinal reflex excitability and its descending control in man. Progress in Neurobiology. 28 (4), 345-376 (1987).

- Pierrot Deseilligny, E., Burke, D. The circuitry of the human spinal cord: its role in motor control and movement disorders. , Cambridge University Press. (2005).

- Duclay, J., Pasquet, B., Martin, A., Duchateau, J. Specific modulation of corticospinal and spinal excitabilities during maximal voluntary isometric shortening and lengthening contractions in synergist muscles. The Journal of Physiology. 589 (Pt. 11), 2901-2916 (2011).

- Grosprêtre, S., Papaxanthis, C., Martin, A. Modulation of spinal excitability by a sub threshold stimulation of M1 area during muscle lengthening. Neuroscience. 263, 60-71 (2014).

- Mynark, R. G. Reliability of the soleus H reflex from supine to standing in young and elderly. Clinical Neurophysiology. 116 (6), 1400-1404 (2005).

- Palmieri, R. M., Hoffman, M. A., Ingersoll, C. D. Intersession reliability for H reflex measurements arising from the soleus peroneal and tibialis anterior musculature. The International Journal of Neuroscience. 112 (7), 841-850 (2002).

- Chen, Y. S., Zhou, S., Cartwright, C., Crowley, Z., Baglin, R., Wang, F. Test retest reliability of the soleus H reflex is affected by joint positions and muscle force levels. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 20 (5), 987-987 (2010).

- Lehman, G. J., McGill, S. M. The importance of normalization in the interpretation of surface electromyography A proof of principle. Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics. 22 (7), 444-446 (1999).

- Lepers, R. Interest and limits of percutaneous nerve electrical stimulation in the evaluation of muscle fatigue. Science, & Motricité. 70 (70), 31-37 (2010).

- Merton, P. A. Voluntary strength and fatigue. The Journal of Physiology. 123, 553-564 (1954).

- Gandevia, S. C. Spinal and supraspinal factors in human muscle fatigue. Physiological Reviews. 81 (4), 1725-1789 (2001).

- Shield, A., Zhou, S. Assessing voluntary muscle activation with the twitch interpolation technique. Sports Medicine. 34 (4), 253-267 (2004).

- Rozand, V., Pageaux, B., Marcora, S. M., Papaxanthis, C., Lepers, R. Does mental exertion alter maximal muscle activation. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience. 8, 755(2014).

- Place, N., Maffiuletti, N. A., Martin, A., Lepers, R. Assessment of the reliability of central and peripheral fatigue after sustained maximal voluntary contraction of the quadriceps muscle. Muscle and Nerve. 35 (4), 486-495 (2007).

- Kannus, P. Isokinetic evaluation of muscular performance: implications for muscle testing and rehabilitation. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 15, Suppl 1. S11-S18 (1994).

- Tucker, K. J., Tuncer, M., Türker, K. S. A review of the H reflex and M wave in the human triceps surae. Human Movement Science. 24 (5-6), 667-688 (2005).

- Taylor, N. A., Sanders, R. H., Howick, E. I., Stanley, S. N. Static and dynamic assessment of the Biodex dynamometer. European Journal of Applied Physiology and Occupational Physiology. 62 (3), 180-188 (1991).

- Sale, D., Quinlan, J., Marsh, E., McComas, A. J., Belanger, A. Y. Influence of joint position on ankle plantarflexion in humans. Journal of Applied Physiology. 52 (6), 1636-1642 (1982).

- Cattagni, T., Martin, A., Scaglioni, G. Is spinal excitability of the triceps surae mainly affected by muscle activity or body position. Journal of Neurophysiology. 111 (12), 2525-2532 (2014).

- Gerilovsky, L., Tsvetinov, P., Trenkova, G. Peripheral effects on the amplitude of monopolar and bipolar H-reflex potentials from the soleus muscle. Experimental Brain Research. 76 (1), 173-181 (1989).

- Schieppati, M. The Hoffmann reflex a means of assessing spinal reflex excitability and its descending control in man. Progress in Neurobiology. 28 (4), 345-376 (1987).

- Hermens, H. J., Freriks, B., Disselhorst Klug, C., Rau, G. Development of recommendations for SEMG sensors and sensor placement procedures. Journal of Electromyography and Kinesiology. 10 (5), 361-374 (2000).

- Kamen, G., Sison, S. V., Du, C. C., Patten, C. Motor unit discharge behavior in older adults during maximal effort contractions. Journal of Applied Physiology. 79 (6), 1908-1913 (1995).

- Neyroud, D., Rüttimann, J., et al. Comparison of neuromuscular adjustments associated with sustained isometric contractions of four different muscle groups. Journal of Applied Physiology. 114, 1426-1434 (2013).

- Rupp, T., Girard, O., Perrey, S. Redetermination of the optimal stimulation intensity modifies resting H-reflex recovery after a sustained moderate-intensity muscle contraction. Muscle and Nerve. 41 (May), 642-650 (2010).

- Zehr, E. P. Considerations for use of the Hoffmann reflex in exercise studies. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 86 (6), 455-468 (2002).

- Gondin, J., Duclay, J., Martin, A. Soleus and gastrocnemii evoked V wave responses increase after neuromuscular electrical stimulation training. Journal of Neurophysiology. 95 (6), 3328-3335 (2006).

- Rochette, L., Hunter, S. K., Place, N., Lepers, R. Activation varies among the knee extensor muscles during a submaximal fatiguing contraction in the seated and supine postures. Journal of Applied Physiology. 95 (4), 1515-1522 (2003).

- Fuglevand, A. J., Zackowski, K. M., Huey, K. A., Enoka, R. M. Impairment of neuromuscular propagation during human fatiguing contractions at submaximal forces. The Journal of Physiology. 460, 549-572 (1993).

- Vandervoort, A. A., McComas, A. J. Contractile changes in opposing muscles of the human ankle joint with aging. Journal of Applied Physiology. 61 (1), 361-367 (1986).

- Grosprêtre, S., Martin, A. Conditioning effect of transcranial magnetic stimulation evoking motor evoked potential on V wave response. Physiological Reports. 2 (11), e12191(2014).

- Allen, G. M., Gandevia, S. C., McKenzie, D. K. Reliability of measurements of muscle strength and voluntary activation using twitch interpolation. Muscle and Nerve. 18 (6), 593-600 (1995).

- Cooper, M. A., Herda, T. J., Walter Herda, A. A., Costa, P. B., Ryan, E. D., Cramer, J. T. The reliability of the interpolated twitch technique during submaximal and maximal isometric muscle actions. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research. 27 (10), 2909-2913 (2013).

- Froyd, C., Millet, G. Y., Noakes, T. D. The development of peripheral fatigue and short term recovery during self paced high intensity exercise. The Journal of Physiology. 591 (Pt 5), 1339-1346 (2013).

- Pierrot Deseilligny, E., Morin, C., Bergego, C., Tankov, N. Pattern of group I fibre projections from ankle flexor and extensor muscles in man. Experimental Brain Research. 42 (3-4), 337-350 (1981).

- Brooke, J. D., McIlroy, W. E., et al. Modulation of H reflexes in human tibialis anterior muscle with passive movement. Brain Research. 766 (1-2), 236-239 (1997).

- Hultborn, H., Meunier, S., Morin, C., Pierrot Deseilligny, E. Assessing changes in presynaptic inhibition of I a fibres a study in man and the cat. The Journal of Physiology. 389, 729-756 (1987).

- Meunier, S., Pierrot Deseilligny, E. Cortical control of presynaptic inhibition of Ia afferents in humans. Experimental Brain Research. 119 (4), 415-426 (1998).

- Aymard, C., Baret, M., Katz, R., Lafitte, C., Pénicaud, A., Raoul, S. Modulation of presynaptic inhibition of la afferents during voluntary wrist flexion and extension in man. Experimental Brain Research. 137 (1), 127-131 (2001).

- Abbruzzese, G., Trompetto, C., Schieppati, M. The excitability of the human motor cortex increases during execution and mental imagination of sequential but not repetitive finger movements. Experimental Brain Research. 111 (3), 465-472 (1996).

- Garland, S. J., Klass, M., Duchateau, J. Cortical and spinal modulation of antagonist coactivation during a submaximal fatiguing contraction in humans. Journal of Neurophysiology. 99, 554-563 (2008).

- Rodriguez Falces, J., Place, N. Recruitment order of quadriceps motor units Femoral nerve vs direct quadriceps stimulation. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 113, 3069-3077 (2013).

- Rodriguez Falces, J., Maffiuletti, N. A., Place, N. Spatial distribution of motor units recruited during electrical stimulation of the quadriceps muscle versus the femoral nerve. Muscle and Nerve. 48 (November), 752-761 (2013).

- Bathien, N., Morin, C. Comparing variations of spinal reflexes during intensive and selective attention (author’s transl). Physiology, & Behavior. 9 (4), 533-538 (1972).

- Earles, D. R., Koceja, D. M., Shively, C. W. Environmental changes in soleus H reflex excitability in young and elderly subjects. The International Journal of Neuroscience. 105 (1-4), 1-13 (2000).

- Paquet, N., Hui Chan, C. W. Human soleus H reflex excitability is decreased by dynamic head and body tilts. Journal of Vestibular Research Equilibrium, & Orientation. 9 (5), 379-383 (1999).

- Miyahara, T., Hagiya, N., Ohyama, T., Nakamura, Y. Modulation of human soleus H reflex in association with voluntary clenching of the teeth. Journal of Neurophysiology. 76 (3), 2033-2041 (1996).

- Pinniger, G. J., Nordlund, M. M., Steele, J. R., Cresswell, a GH reflex modulation during passive lengthening and shortening of the human triceps surae. Journal of Physiology. 534 (Pt 3), 913-923 (2001).

- Tallent, J., Goodall, S., Hortobágyi, T., St Clair Gibson, A., French, D. N., Howatson, G. Repeatability of corticospinal and spinal measures during lengthening and shortening contractions in the human tibialis anterior muscle). PLoS ONE. 7 (4), e35930(2012).

- Grospretre, S., Martin, A. H. reflex and spinal excitability methodological considerations. Journal of Neurophysiology. 107 (6), 1649-1654 (2012).

- Hugon, M. Methodology of the Hoffmann reflex in man. New Developments in Electromyography and Chemical Neurophysiology. 3m, 277-293 (1973).

- Bigland Ritchie, B., Zijdewind, I., Thomas, C. K. Muscle fatigue induced by stimulation with and without doublets. Muscle and Nerve. 23 (9), 1348-1355 (2000).

- Kent Braun, J. A., Le Blanc, R. Quantitation of central activation failure during maximal voluntary contractions in humans. Muscle and Nerve. 19 (7), 861-869 (1996).

- Herbert, R. D., Gandevia, S. C. Twitch interpolation in human muscles mechanisms and implications for measurement of voluntary activation. Journal of Neurophysiology. 82, 2271-2283 (1999).

- Miller, M., Downham, D., Lexell, J. Superimposed single impulse and pulse train electrical stimulation A quantitative assessment during submaximal isometric knee extension in young healthy men. Muscle and Nerve. 22 (8), 1038-1046 (1999).

- Button, D. C., Behm, D. G. The effect of stimulus anticipation on the interpolated twitch technique. Journal of Sports Science and Medicine. 7 (4), 520-524 (2008).

- Goss, D. a, Hoffman, R. L., Clark, B. C. Utilizing Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation to Study the Human Neuromuscular System. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (59), e3387(2012).

- Sartori, L., Betti, S., Castiello, U. Corticospinal excitability modulation during action observation. Journal Of Visualized Experiments: Jove. (82), 51001(2013).

- Rozand, V., Lebon, F., Papaxanthis, C., Lepers, R. Does a mental training session induce neuromuscular fatigue. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 46 (10), 1981-1989 (2014).

- Rozand, V., Cattagni, T., Theurel, J., Martin, A., Lepers, R. Neuromuscular fatigue following isometric contractions with similar torque time integral. International Journal of Sports Medicine. 36, 35-40 (2015).

- Belanger, A. Y., McComas, A. J. Extent of motor unit activation during effort. Journal of Applied Physiology. 51 (5), 1131-1135 (1981).

- Morse, C. I., Thom, J. M., Davis, M. G., Fox, K. R., Birch, K. M., Narici, M. V. Reduced plantarflexor specific torque in the elderly is associated with a lower activation capacity. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 92 (1-2), 219-226 (2004).

- Dalton, B. H., McNeil, C. J., Doherty, T. J., Rice, C. L. Age related reductions in the estimated numbers of motor units are minimal in the human soleus. Muscle and Nerve. 38 (3), 1108-1115 (2008).

- Hunter, S. K., Todd, G., Butler, J. E., Gandevia, S. C., Taylor, J. L. Recovery from supraspinal fatigue is slowed in old adults after fatiguing maximal isometric contractions. Journal of Applied Physiology. 105 (4), 1199-1209 (2008).

- Jakobi, J. M., Rice, C. L. Voluntary muscle activation varies with age and muscle group. Journal of Applied Physiology. 93 (2), 457-462 (2002).

- Lepers, R., Millet, G. Y., Maffiuletti, N. a Effect of cycling cadence on contractile and neural properties of knee extensors. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 33 (11), 1882-1888 (2001).

- Duchateau, J., Hainaut, K. Isometric or dynamic training differential effects on mechanical properties of a human muscle. Journal of Applied Physiology. 56 (2), 296-301 (1984).

- Millet, G. Y., Martin, V., Martin, A., Vergès, S. Electrical stimulation for testing neuromuscular function From sport to pathology. European Journal of Applied Physiology. 111, 2489-2500 (2011).

- Cattagni, T., Scaglioni, G., Laroche, D., Van Hoecke, J., Gremeaux, V., Martin, A. Ankle muscle strength discriminates fallers from non fallers. Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 6, 336(2014).

- Horstman, A. M., Beltman, M. J., et al. Intrinsic muscle strength and voluntary activation of both lower limbs and functional performance after stroke. Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging. 28 (4), 251-261 (2008).

- Sica, R. E., Herskovits, E., Aguilera, N., Poch, G. An electrophysiological investigation of skeletal muscle in Parkinson’s disease. Journal of the Neurological Sciences. 18 (4), 411-420 (1973).

- Knikou, M., Mummidisetty, C. K. Locomotor Training Improves Premotoneuronal Control after Chronic Spinal Cord Injury. Journal of Neurophysiology. 111 (11), 2264-2275 (2014).

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionExplore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved