The Ames Room

Обзор

Source: Laboratory of Jonathan Flombaum—Johns Hopkins University

The most difficult challenge of visual perception is often described as one of recovering information about three-dimensional space from two-dimensional retinas. The retina is the light-sensitive tissue inside the human eye. Light is reflected from objects in the world, casting projections on the retina that stimulate these light sensitive cells. Objects that are side-by-side in the world will produce side-by-side stimulations on the retina. But objects that are more distant from the observer cannot produce more distant stimulations, compared to nearby objects that is. Distance-the third dimension-is collapsed on the retina.

So how do we see in three dimensions? The answer is that the human brain applies a variety of assumptions and heuristics in order to make inferences about distances given the inputs received on the retina. In the study of perception, there is a long tradition of using visual illusions as a way to identify some of these heuristics and assumptions. If researchers know what tricks the brain is using, they should be able to trick the brain into seeing things inaccurately. This video will show you how to build an Ames Room, a visual illusion that illustrates one of the assumptions applied by the human visual system in order to recover visual depth.

Процедура

1. Materials

- To build an Ames Room you will need four pieces of cardboard, each 1-ft high. The four pieces should vary in length, including a 2-ft piece, two 1-ft pieces, and one piece that is 1.5-ft long.

- You will also need two figurines of some kind, action figures, toy soldiers, even stuffed animals will do the the trick. The two should be roughly the same height and shorter than ¾-ft tall.

- A box cutter and glue or tape will also be necessary.

2. Assembling the Ames Room

- Start with one of the two 1-ft pieces of cardboard. Put a penny on it, right in the center, and use the box cutter to cut around the penny to produce a hole. This will be the aperture for the Ames Room.

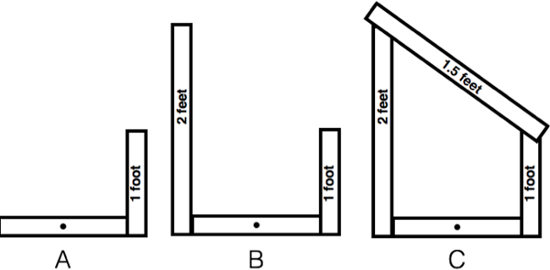

- Figure 1 schematically depicts the three initial steps of assembly, described in 2.2.-2.4. Stand up the piece with the hole, and to its right attach the other 1-ft piece of cardboard, so that the two form a right angle. You will have an object that looks like the one in Figure 1a, when looked at from above.

Figure 1: Building an Ames Room amounts to building (from cardboard) an irregular four-sided polygon. The first step is to carve a penny-sized peephole in a 1-ft piece of cardboard. Then attach an equally sized piece of cardboard to produce a standing, right-angle like the one shown in (A). Next, attach a 2-ft piece of cardboard, also at a flush right angle, on the left of the piece with the peephole. The outcome is schematized in B. Finally, attach a 1.5-ft piece of cardboard to close the polygon. The final product is shown in C.

- Now attach the two-ft piece on the other side of the piece with the aperture. You will have an object that looks like the one in Figure 1b when looked at from above.

- Finally, attach the 1.5-ft piece to close the structure. You will have a four-sided polygon like the one in Figure 1c.

- To complete the Ames Room and produce the illusion take the two figurines and place one at each of the vertices where the 1.5-ft cardboard attaches to the rest of the structure. In Figure 2, these two locations are denoted by green circles. The figurines should be facing the aperture.

Figure 2: The green dots denote the relative placement of figurines within the Ames Room. To produce the strongest illusion, it is critical that the two figurines be placed at the two non-right angle vertices of the polygon.

3. Seeing the illusion

- To see the illusion, just look into the Ames Room by looking through the aperture.

Результаты

What do you see when you look into the Ames Room? Figure 3 schematizes the effect-the figurine on the right should look much larger than the one on the left, even though you know they are the same size.

Figure 3: Schematic representation of what people see in the Ames Room, compared to the fact of the matter, i.e., what is actually there. The right side of the figure shows the true relative sizes and distances of the figurines in the room: they are equally tall, and the one on the left is farther away from the viewer. But when looking through the aperture, the illusion, depicted on the left, is that the figurine on the left looks to be standing next to the person on the right, and that figurine also look much smaller.

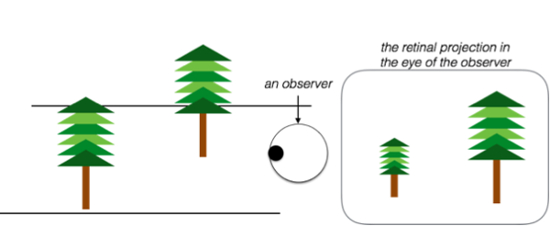

What's going on? Before explaining the Ames Room in particular, we need to consider the general problem of perceiving size and depth at the same time. The projection that an object produces on the retina will vary in size in proportion to the size of the object; but projections will also vary in size as a function of an object's distance from the surface it projects on (in this case the retina). In other words, a very large projection on the retina could mean that the relevant object is very large and reasonably far from the observer, or it could mean that the relevant object is small, but very close by. Big objects can cast small projections when they are far away, and small objects can cast large projections when they are nearby. Separating size and distance is one of the major challenges to 3D vision. Figure 4 schematizes this general problem in reference to two trees of the same size but at different relative distances from an observer.

Figure 4: A schematic diagram to illustrate the problem of simultaneously perceiving size and distance. On the left side of the figure are two trees of equal height. To their right, is an observer, denoted as an eye. Because of the relative position of the observer to the trees, and the physics of optical projection, the tree to the left of the observer will cast a much smaller reflection on the retina of the observer, in comparison to the tree on the right. This is because the tree on the right is closer to the observer. But given the projections on the two dimensional retina, what should the observer think, is the tree on the left smaller, or just farther away?

Returning to the Ames Room now, what that specific illusions demonstrates is one of the tricks the brain uses to estimate object sizes and object distances. Specifically, the brain applies an assumption: it assumes that in the absence of strong countervailing evidence, that structures connect to one another at right-angles.

Let's look back at the Ames Room configuration now to understand how the illusion exploits that assumption. The walls of the room are all the same color, and looking through a small aperture people cannot tell that the far wall is diagonal. So the brain assumes that it is straight-that the Ames Room is rectangular as opposed to irregular. The implication of that assumption is that the figurine on the left side of the room (relative to the aperture view) is much closer to the observer than it actually is. In fact, the implication is that it is at the same distance as the figurine on the right. Because it is actually farther away, the figurine on the left projects a smaller image on the observer's retina than the figurine on the right. But the brain has made an assumption that implies that they are the same distance. So what could account for the differences in the sizes of the figurine projections? The brain get's tricked: it reasons that the figurine on the left must actually be much smaller than the one the on right producing the illusion. Figure 5 walks through this reasoning in relation to the geometry of the Ames Room.

Figure 5. The Ames Room tricks the human brain, producing the size illusion, by taking advantage of an assumption that the brain makes about geometry. Specifically, the human brain assumes that walls attach to one another at right angles. Looking through the aperture of the Ames Room, the brain cannot gather countervailing evidence, and so it applies that assumption. The result is that it thinks the Ames Room is rectangular, with the far wall occupying the positions of the dotted line in the figure. The implication, then, is that the two figurines are side-by-side, and that the left figurine is much closer to the observer than is accurate. The brain then asks itself why two side-by-side objects cast so differently sized projections on the retina. The answer it gives: they must be different sizes.

Заявка и Краткое содержание

Understanding how humans perceive the visual world in 3D has been a major area of research focus and a major achievement of the modern study of perception. Some of the important applications that have arisen, as a result, are in the development of 3D and virtual reality viewing technology. The Ames Room specifically has been used for a long time in the movies, as a sort of special effect. Suppose a movie needs to depict a giant, or someone very small. Shooting interior scenes inside an Ames Room can produce the illusion for the viewer that some people are much larger (or smaller) than they actually are. The camera, is after all an aperture.

Перейти к...

Видео из этой коллекции:

Now Playing

The Ames Room

Sensation and Perception

17.4K Просмотры

Color Afterimages

Sensation and Perception

11.1K Просмотры

Finding Your Blind Spot and Perceptual Filling-in

Sensation and Perception

17.3K Просмотры

Perspectives on Sensation and Perception

Sensation and Perception

11.8K Просмотры

Motion-induced Blindness

Sensation and Perception

6.9K Просмотры

The Rubber Hand Illusion

Sensation and Perception

18.3K Просмотры

Inattentional Blindness

Sensation and Perception

13.2K Просмотры

Spatial Cueing

Sensation and Perception

14.9K Просмотры

The Attentional Blink

Sensation and Perception

15.8K Просмотры

Crowding

Sensation and Perception

5.7K Просмотры

The Inverted-face Effect

Sensation and Perception

15.5K Просмотры

The McGurk Effect

Sensation and Perception

16.0K Просмотры

Just-noticeable Differences

Sensation and Perception

15.3K Просмотры

The Staircase Procedure for Finding a Perceptual Threshold

Sensation and Perception

24.3K Просмотры

Object Substitution Masking

Sensation and Perception

6.4K Просмотры

Авторские права © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. Все права защищены