Method Article

Transposon-insertion Sequencing as a Tool to Elucidate Bacterial Colonization Factors in a Burkholderia gladioli Symbiont of Lagria villosa Beetles

In This Article

Summary

This is an adapted method for identifying candidate insect colonization factors in a Burkholderia beneficial symbiont. The beetle host is infected with a random mutant library generated via transposon mutagenesis, and library complexity after colonization is compared to a control grown in vitro.

Abstract

Inferring the function of genes by manipulating their activity is an essential tool for understanding the genetic underpinnings of most biological processes. Advances in molecular microbiology have seen the emergence of diverse mutagenesis techniques for the manipulation of genes. Among them, transposon-insertion sequencing (Tn-seq) is a valuable tool to simultaneously assess the functionality of many candidate genes in an untargeted way. The technique has been key to identify molecular mechanisms for the colonization of eukaryotic hosts in several pathogenic microbes and a few beneficial symbionts.

Here, Tn-seq is established as a method to identify colonization factors in a mutualistic Burkholderia gladioli symbiont of the beetle Lagria villosa. By conjugation, Tn5 transposon-mediated insertion of an antibiotic-resistance cassette is carried out at random genomic locations in B. gladioli. To identify the effect of gene disruptions on the ability of the bacteria to colonize the beetle host, the generated B. gladioli transposon-mutant library is inoculated on the beetle eggs, while a control is grown in vitro in a liquid culture medium. After allowing sufficient time for colonization, DNA is extracted from the in vivo and in vitro grown libraries. Following a DNA library preparation protocol, the DNA samples are prepared for transposon-insertion sequencing. DNA fragments that contain the transposon-insert edge and flanking bacterial DNA are selected, and the mutation sites are determined by sequencing away from the transposon-insert edge. Finally, by analyzing and comparing the frequencies of each mutant between the in vivo and in vitro libraries, the importance of specific symbiont genes during beetle colonization can be predicted.

Introduction

Burkholderia gladioli can engage in a symbiotic association with Lagria villosa beetles, playing an important role in defense against microbial antagonists of the insect host4,5,6. Female beetles house several strains of B. gladioli in specialized glands accessory to the reproductive system. Upon egg-laying, females smear B. gladioli cells on the egg surface where antimicrobial compounds produced by B. gladioli inhibit infections by entomopathogenic fungi4,6. During late embryonic development or early after the larvae hatch, the bacteria colonize cuticular invaginations on the dorsal surface of the larvae. Despite this specialized localization and vertical transmission route of the symbionts, L. villosa can presumably also acquire B. gladioli horizontally from the environment4. Furthermore, at least three strains of B. gladioli have been found in association with L. villosa4,6. Among these, B. gladioli Lv-StA is the only one that is amenable to cultivation in vitro.

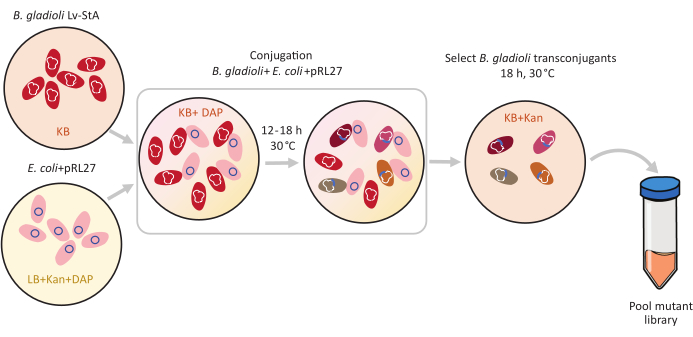

B. gladioli Lv-StA has a genome size of 8.56 Mb6 and contains 7,468 genes. Which of these genes are important for B. gladioli bacteria to colonize the beetle host? To answer this question, we used transposon-insertion sequencing (Tn-seq), an explorative method to identify conditionally essential microbial genes1,2,3. A mutant library of B. gladioli Lv-StA was created using a Tn5 transposon. Through conjugation from Escherichia coli donor cells to B. gladioli Lv-StA, a pRL27 plasmid carrying the Tn5 transposon and an antibiotic resistance cassette flanked by inverted repeats was transferred (Figure 1). Thereby, a set of mutants that individually carry disruptions of 3,736 symbiont genes was generated (Figure 2).

The mutant pool was infected onto beetle eggs to identify the colonization factors and, as a control, was also grown in vitro in King's B (KB) medium. After allowing sufficient time for colonization, hatched larvae were collected and pooled for DNA extraction. Fragments of DNA containing the transposon insert and the flanking genomic region of B. gladioli Lv-StA were selected using a modified DNA library preparation protocol for sequencing. Read quality processing followed by analysis with DESeq2 was carried out to identify specific genes crucial for B. gladioli Lv-StA to colonize L. villosa larvae when transmitted via the egg surface.

Protocol

1. Media and buffer preparation

- Prepare KB and LB media and agar plates as given in Table 1, and autoclave at 121 °C, 15 psi, 20 min.

- Add 50 µg/mL filter-sterilized kanamycin and 300 µM filter-sterilized 2,6-diaminopimelic acid (DAP) to the autoclaved LB medium before culturing E.coli WM3064 + pRL27.

- Add 50 µg/mL filter-sterilized kanamycin to the autoclaved KB agar to pour plates needed for selecting successful B. gladioli Lv-StA transconjugants.

- Prepare 1x phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) by mixing the following components: NaCl 8 g/L, KCl 0.201 g/L, Na2HPO4 1.42 g/L, and KH2PO4 0.272 g/L. Dissolve the salts in distilled water and autoclave the mixture at 121 °C, 15 psi, 20 min before use. Store at room temperature.

- Prepare a 2x Bind-and-wash buffer by dissolving the following components: 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 1 mM ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA), and 2 M NaCl in distilled water. Filter-sterilize the mixture before use. Store at room temperature.

- Prepare 1x Low-TE by dissolving 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) and 0.1 mM EDTA in double-distilled water. Sterilize by autoclaving at 121 °C, 15 psi, 20 min. Store at room temperature.

2. Conjugation to generate the transposon mutant library

Figure 1: Conjugation protocol steps. The conjugation recipient Burkholderia gladioli Lv-StA (red) and donor Escherichia coli containing the pRL27 plasmid (pink) are grown in KB agar and LB, respectively, supplemented with kanamycin and DAP. After conjugative transfer of the plasmid for 12-18 h at 30 °C, the transconjugant B. gladioli cells are selected on KB containing kanamycin and pooled together. Abbreviations: DAP = 2,6-diaminopimelic acid; Kan = kanamycin. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

- Under a sterile hood, inoculate a fresh donor culture of Escherichia coli WM3064 + pRL27 in 10 mL of LB medium supplemented with kanamycin and DAP. Inoculate Burkholderia gladioli Lv-StA recipient cells in 5 mL of KB medium. Incubate the cultures at 30 °C overnight on a shaker at 250 rpm.

- After overnight growth, centrifuge 4 mL of each of the cultures at 9,600 × g for 6 min to pellet the cells. Discard the supernatant.

- Under a sterile hood, wash the pelleted cell cultures in KB medium containing DAP and finally resuspend the cultures separately in 4 mL of KB + DAP medium.

- In a fresh 15 mL tube, mix 250 µL of the washed E. coli donor cells with 1 mL of the washed B. gladioli Lv-StA recipient cells.

- Spot 10 µL of this conjugation cell mixture on KB agar plates containing DAP. Allow the plate to rest undisturbed in the sterile hood at room temperature for 1 h. Then, incubate the plates with the conjugation spots at 30 °C for 12-18 h.

NOTE: The conjugation period can be adjusted according to the target species. However, a long conjugation period increases the risk for double insertions or plasmid integration into the genome. For slow-growing bacteria, allow for longer conjugation periods. - After incubation, add 2-4 mL of 1x PBS into the plates under a sterile hood and use a cell scraper to release the grown bacterial conjugation spots from the agar. Pipette the conjugated-cell-mix into 2 mL microfuge tubes.

- Pellet the cells by centrifuging at 9,600 × g for 2 min. Discard the supernatant and wash the pellet twice in 1 mL of 1x PBS by pipetting up and down. Resuspend the final pellet in 1200 µL of 1x PBS. Make dilutions before plating if the number of cells in the mixture is above 1 × 104.

- Mix well and spread 200 µL of the cell mixture on large KB agar plates (6 or more, if required) supplemented with kanamycin and incubate at 30 °C overnight.

NOTE: Target mutant colonies appear within 30 h on the selective agar plates. Due to the antibiotic resistance marker, only mutated colonies appear on the selective agar plate. Therefore, all colonies are expected to be successful transconjugants. - Count the total number of transconjugant colonies on three plates and extrapolate to calculate the approximate number of mutants obtained in all the plates. To increase the chances of obtaining a representative library, ensure that the total number of colonies is several fold higher than the total number of genes in the genome. To confirm the success of conjugation, perform a PCR targeting the insertion cassette using 10-20 sample colonies, as described in section 3.

NOTE: The aim is to ensure that the number of colonies is at least 10-fold the number of genes in the whole genome, in this case, >75,000 mutants. However, it is generally challenging to accurately estimate the number of colonies that would correspond to a fully representative library. The number of unique genes mutated is not evident at this point, given that disruptions in essential genes are not captured, there are often multiple different mutation sites for the same gene, and mutations generated with Tn5 transposons are not entirely random. - Under a sterile hood, scrape colonies from the plates by adding 1-2 mL of 1x PBS on the agar. Pool the cell mixture scraped off from the plates into 50 mL tubes. Vortex the library to mix thoroughly and then split 4 mL of the pooled mutant library into several cryotubes. Add 1 mL of 70% glycerol to the tubes and store at -80 °C.

3. PCR and gel electrophoresis to confirm successful insertions in B. gladioli Lv-StA

- To confirm the presence of the insertion, pick individual mutant colonies from the selection plates in step 2.9 and perform a PCR targeting the insertion cassette using the primers listed in Table 2. Prepare the PCR master mix according to Table 3 and set conditions in the thermal cycler as described in Table 4.

- Run the PCR products on a 1.6% agarose gel by electrophoresis (250 V, 40 min) to check if the amplified DNA fragments are of the expected length of 1580 bp.

4. Mutant pool infection on beetle eggs

- Library washing steps

- Thaw an aliquot of the prepared mutant library on ice. Centrifuge at 2,683 × g for 10 min and remove the supernatant. Under a sterile hood, wash the cells with 4 mL of 1x PBS to remove any remaining medium from the cells. Resuspend the cells in 4 mL of 1x PBS.

- Count the number of cells in an aliquot of the library using a cell counting chamber. Dilute a part of the library to 2 × 106 cells/µL in 1x PBS.

- Vortex the library aliquot thoroughly to mix the whole library homogenously before taking the required volume.

- Egg clutch sterilization and in vivo infection

- Select an L. villosa egg clutch. Count the number of eggs and continue if the clutch contains more than 100 eggs.

- Sterilize the entire egg clutch.

- Add 200 µL of 70% ethanol and gently wash the eggs for 5 min. Remove the ethanol and wash the eggs twice with autoclaved water.

- Add 200 µL of 12% bleach (NaOCl) and gently wash the eggs for 30 s. Remove the bleach immediately and wash the eggs again three times with 200 µL of autoclaved water.

- Infect 2 × 106 cells/µL of the washed mutant library on the sterilized egg clutch (2.5 µL per egg).

- Two days after the infected beetle larvae hatch, collect 100 2nd instar larvae per 1.5 mL microfuge tube and store at -80 °C.

- In vitro mutant library control

- Under a sterile hood, inoculate 250 µL of 2 × 106 cells/µL of the washed mutant library in 10 mL of KB medium containing kanamycin.

- Incubate the in vitro mutant culture at 30 °C for 20 h.

NOTE: Calculate the duration of incubation to match the approximate number of generations of WT B. gladioli Lv-StA in vivo during colonization. - After the 20 h incubation, add an equal volume of 70% glycerol to the in vitro mutant culture and store it at -80 °C.

5. Infected beetles and in vitro mutant library DNA extraction

NOTE: DNA extractions were performed using a DNA and RNA purification kit according to the manufacturer's protocol briefly outlined below.

- Homogenize pooled larvae (maximum of 4 mg per microfuge tube) by adding 1-2 mL of liquid nitrogen and crushing with a pestle.

- Thaw the in vitro grown mutant cultures from glycerol stocks on ice. Pellet the cells by centrifuging at 9,600 × g for 10 min before cell lysis.

- Add 300 µL of Tissue and Cell lysis solution to the in vitro and in vivo samples. Add 5 µL of 10 mg/mL Proteinase K, incubate the mix at 60 °C for 15 min, and then place on ice for 3-5 min.

- Add 150 µL of protein precipitation reagent to the lysates and vortex thoroughly. Pellet the protein debris by centrifuging at 9,600 × g for 10 min.

- Transfer the supernatant to a 1.5 mL microfuge tube. Add 500 µL of isopropanol to the supernatant and gently invert the tubes at least 40 times before incubating at -20 °C for 1 h or overnight.

- Pellet the precipitated DNA by centrifuging at 9,600 × g for 10 min. Discard the supernatant and add ice-cold 70% ethanol to the DNA pellet.

- Centrifuge at ≥10,000 × g for 5 min. Discard the supernatant and leave the samples to air-dry for at least 1 h.

- Resuspend the DNA from the in vitro and in vivo samples in 100 µL of Low-TE buffer.

- Store the samples at -20 °C.

6. Sequencing library preparation

NOTE: The protocol and reagents for DNA library preparation are adapted and modified from the instructions provided by the manufacturer of the DNA library preparation kit.

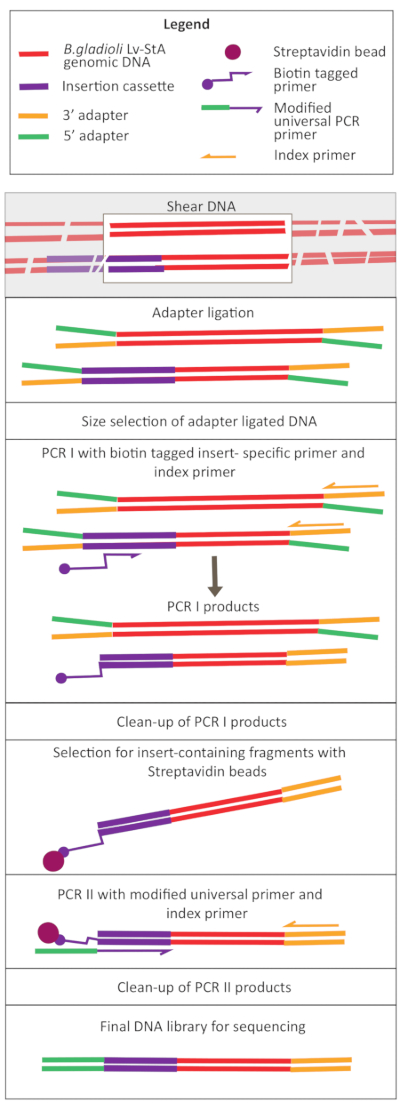

Figure 2: Schematic of the DNA library preparation steps. After shearing and adapter ligation, the modified protocol includes a streptavidin bead-selection step to enrich DNA fragments containing the insertion cassette. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

- Dilute the samples to 20 ng/µL concentration and volume of 100 µL and keep them on ice.

- Shear in vivo and in vitro sample DNA using an ultrasonicator. Set the ultrasonicator at 70% power. Vortex the samples briefly and shear for 1 min 30 s.

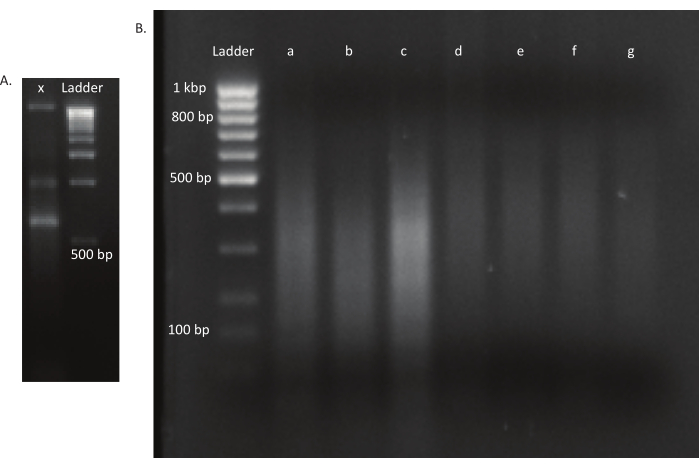

NOTE: The settings for the ultrasonicator will differ among instruments. In this case, the fragment size was 200-400 bp, which is appropriate for this sequencing approach of 150 bp, paired-end (see step. 9.1). The shearing parameters can be adjusted according to the experimenter's requirements. - Check if the DNA was sheared to the desired size range (in this case, 200-400 bp). Load 5 µL of the unsheared and sheared DNA after mixing with gel loading dye in a 1:1 ratio on a 1.6% agarose gel run at 250 V for 40 min (Figure 3A,B).

- Preparation of fragment ends required for adapter ligation

- To 50 µL of the sheared DNA, add the end preparation reagents given in the library preparation kit: 3 µL of the enzyme mix and 7 µL of reaction buffer and mix well by pipetting. Set a thermal cycler with a heated lid at ≥ 75 °C and incubate the samples for 30 min at 20 °C and 30 min at 65 °C. Hold at 4 °C.

- Adapter ligation

- For adapter ligation, add the following reagents to the products of the end preparation step: 30 µL Ligation Master Mix, 1 µL Ligation Enhancer, and 2.5 µL diluted Adapter. Mix thoroughly by pipetting and incubate the sample for 15 min at 20 °C in the thermal cycler with the heated lid off.

- After 15 min, add 3 µL of the enzyme (uracil DNA glycosylase + DNA glycosylase-lyase Endonuclease VIII) (see the Table of Materials). Mix well by pipetting and incubate the sample for 15 min at 37 °C in a thermal cycler with the lid heated at ≥47 °C.

NOTE: The protocol can be paused at this step, and the samples can be stored at -20 °C.

- Size selection of adapter-ligated DNA targeting fragments of 250 bp

- Vortex the magnetic bead solution (see the Table of Materials) and place it at room temperature for 30 min before use.

- Add 0.3x of beads to 96.5 µL of the ligated DNA mixture and mix by pipetting thoroughly. Incubate the bead mixture for 5 min.

NOTE: The presence of salts and polyethylene glycol in the bead mixture facilitates the precipitation of DNA fragments on the beads. A low ratio of beads to DNA molecules leads to the binding of only larger DNA fragments to the beads. In this case, DNA fragments above 250 bp in length are bound to the beads. - Place the tubes on a magnetic stand to pull down the beads and remove DNA fragments of unwanted size. Let the beads settle for 5 min and then transfer the clear supernatant to a new microfuge tube (keep the supernatant).

- Add 0.15x of fresh beads to the supernatant and mix by pipetting well. Incubate the bead mixture for 5 min and then place the tubes on a magnetic stand to pull down the beads bound to the target DNA. Wait for 5 min and then discard the supernatant (keep the beads).

NOTE: This ratio of beads to DNA leads to the binding of fragments of the desired 250 bp size. - With the beads on the magnetic stand, add 200 µL of 80% ethanol (freshly prepared) and wait for 30 s. Pipette out and discard the ethanol wash carefully without disturbing the beads on the magnetic stand. Repeat this step.

- After the last wash, remove traces of ethanol from the beads and then air-dry the beads for 2 min until they appear glossy but not completely dried out. Do not over-dry the beads.

- Remove the tubes from the magnetic stand and add 17 µL of 10 mM Tris-HCl or 0.1x TE (Low-TE). Mix by pipetting ~10 times and incubate the mixture at room temperature for 2 min.

- Place the tubes back on the magnetic stand and wait for 5 min. Once the beads have settled down, transfer the DNA supernatant to a new tube.

- PCR I to add biotin tag to DNA fragments containing the insertion cassette

- Add a biotinylated primer tag to the DNA fragments containing the Tn5-insertion cassette by using the transposon-specific biotinylated primer (Table 5) and an index primer. Prepare the PCR master mix according to Table 6 and follow the PCR conditions for the thermal cycler listed in Table 7.

- Clean-up of PCR I without size selection

- Vortex 0.9x beads and place them at room temperature for at least 30 min before clean-up.

- Add 0.9x beads to the PCR products and mix thoroughly.

- Place the beads on a magnetic stand to pull down the beads.

- Remove the clear supernatant and wash the bead-bound-DNA with 200 µL of freshly prepared 80% ethanol twice.

- Remove the ethanol after the wash steps and air dry the beads until they look glossy but not too dry.

- Add 32 µL of 10 mM Tris-HCl or 0.1X TE (Low-TE) and incubate the beads for 5 min. Place the mixture back on the magnetic stand and transfer the supernatant to a fresh microfuge tube.

- Binding biotinylated DNA fragments to streptavidin beads

- Resuspend 32 µL of streptavidin beads in 1x Bind-and-wash buffer. Wash the beads with the buffer three times while placed on a magnetic stand.

- Add 32 µL of 2x Bind-and-wash buffer and resuspend the beads. To this, add 32 µL of the cleaned-up PCR 1 products. Mix thoroughly and incubate at room temperature for 30 min.

- Place the bead-DNA mixture on a magnetic stand for 2 min. Pipette out the supernatant as biotin-tagged DNA containing the insertion edge binds to streptavidin on the beads.

- Wash the beads with 500 µL of 1x Bind-and-wash buffer and then wash the beads with 200 µL of Low-TE. Resuspend the DNA-bound beads in 17 µL of Low-TE.

- PCR II to add adapters to the fragments containing the insertion cassette edge

- Prepare a master mix, as shown in Table 8, using the index primers and modified universal PCR primers listed in Table 5. Add 15 µL of the DNA-bound streptavidin beads from the previous step to the PCR mix. See Table 7 for the thermal cycler conditions.

- Clean up the PCR products without size selection as given in step 6.8 of this protocol. Elute the final DNA products in 30 µL of molecular-grade water.

- Store the samples at -20 °C and use them for sequencing.

7. Sequencing and analysis

- Sequence the library using high-throughput sequencing technology. Adjust the sequencing depth depending on the transposon library size, as noted below. Assess the read quality with FastQC7. Select reads containing the Tn5-insertion edge on the 5' end of the read and remove the insertion edge sequence using Cutadapt8 and/or Trimmomatic9.

NOTE: Here, a paired-end sequencing approach was used to target 150 bp per read and a total of 8 Mio reads. To obtain a representative dataset, ensure that the total number of sequenced reads exceeds the maximum possible number of mutants in the library, i.e., the total estimated number of colonies from step 2.9. As a reference, this protocol aimed for 40-fold of the maximum possible library size. Other successful studies using Tn-seq for a similar purpose sequenced a total number of reads close to 25-fold of the actual number of unique insertions in the corresponding mutant library22,23. - Considering that mutations at the ends of genes are not functionally disruptive, trim 5% off both ends of gene annotations of the reference genome GFF file. Map the trimmed reads to the reference genome using Bowtie210.

- Calculate the number of insertions from the number of unique 5' positions in the alignment BAM file.

- Using FeatureCounts11, obtain the number of hit genes for each replicate sample.

- Using the DESeq212 package in RStudio, calculate the difference in mutant abundances between different conditions.

Results

Host-associated bacteria can employ several factors to establish an association, including those mediating adhesion, motility, chemotaxis, stress responses, or specific transporters. While factors important for pathogen-host interactions have been reported for several bacteria13,14,15,16,17,18, including members of the genus Burkholderia19,20, fewer studies have explored the molecular mechanisms used by beneficial symbionts for colonization21,22,23. Using transposon insertion sequencing, the aim was to identify molecular factors that enable B. gladioli to colonize L. villosa beetles.

Transposon-mediated mutagenesis was performed using the pRL27 plasmid, which carries a Tn5 transposon and a kanamycin resistance cassette flanked by invert repeat sites. The plasmid was introduced into the target B. gladioli Lv-StA cells by conjugation with the plasmid donor E. coli WM3064 strain (as shown in Figure 1). After conjugation, the conjugation mix containing B. gladioli recipient and E. coli donor cells were plated on selective agar plates containing kanamycin. The absence of DAP on the plates eliminated the donor E. coli cells, and the presence of kanamycin selected for successful B. gladioli Lv-StA transconjugants. The pooled B. gladioli Lv-StA mutant library obtained from harvesting the 100,000 transconjugant colonies was prepared for sequencing using a modified DNA library preparation kit and custom primers. Figure 2 highlights the DNA library preparation steps. Sequencing yielded 4 Mio paired reads; 3,736 genes out of 7,468 genes in B. gladioli Lv-StA were disrupted.

To identify mutants that were colonization-defective in the host, the B. gladioli Lv-StA mutant library was infected on the beetle eggs and grown in vitro in KB medium as a control. The in vivo colonization bottleneck size was calculated before the experiment. A known number of B. gladioli Lv-StA cells was infected on beetle eggs, and the number of colonizing cells in freshly hatched first instar larvae was obtained by plating a suspension from each larva and counting colony-forming units per individual. These calculations were done to ensure that the number of colonizing cells is enough to assess all or a high percentage of the mutants in the library for their ability to colonize the host. Additionally, the growth time between in vitro and in vivo conditions was normalized based on the number of bacterial generations to make these samples comparable.

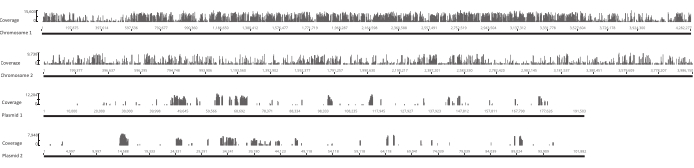

After the eggs hatched, 1,296 larvae were collected in 13 pools. The corresponding in vitro mutant cultures were grown and stored as glycerol stocks. DNA of the in vivo and in vitro grown mutant libraries was extracted and fragmented in an ultrasonicator. Figure 3 shows the size distribution of the sheared DNA, where the majority of the fragments span between 100 and 400 bp, as expected. This step was followed by the modified DNA library preparation protocol for sequencing. At each step of the protocol, the concentration of remaining DNA was checked to ensure that the steps were performed correctly and to track losses of DNA. A quality check (see the Table of Materials) before sequencing revealed that the DNA libraries contained unexpectedly large (>800 bp) DNA fragments, and this was more pronounced in the in vivo libraries. Given the difficulty in optimizing the clustering of fragments in the sequencing lanes, it was necessary to increase the sequencing depth to 10 Mio paired reads in the in vivo libraries to attain the desired number of reads. The analysis of the sequencing results revealed that an average of 4 Mio reads in the in vivo libraries and 3.1 Mio reads in the in vitro libraries contained the Transposon edge in the 5' end of Read-1 (Table 9), which was satisfactory for this experiment. The distribution of the 24,224 unique insertions across the B. gladioli genome in the original library is shown in Figure 4. An analysis carried out using DESeq2 revealed that the abundances of 271 mutants were significantly different between the in vivo and in vitro conditions.

Figure 3: Agarose gels of a mutant and DNA libraries. (A) Agarose gel with unsheared DNA of a mutant in lane x and a 1 kbp ladder for scale. (B) Gel with sheared DNA library. The band sizes of the ladder in the first lane are indicated on the left side. The first three lanes a, b, and c contain sheared DNA fragments of the in vivo libraries. Lanes d, e, f, and g contain sheared DNA fragments of the in vitro libraries. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 4: Location of unique insertion sites in the original library across the four replicons in the Burkholderia gladioli Lv-StA genome. Each bar along the x-axis is located at a site of insertion. The height of a bar along the y-axis corresponds to the number of reads associated with that site. Note that the two chromosomes and two plasmids are shown in full length and thus have different scales on the x-axis. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

| King’s B medium/ agar | |

| Peptone (soybean) | 20 g/L |

| K2HPO4 | 1.5 g/L |

| MgSO4.7H2O | 1.5 g/L |

| Agar | 15 g/L |

| Dissolved in distilled water | |

| LB medium/agar | |

| Tryptone | 10 g/L |

| Yeast extract | 5 g/L |

| NaCl | 10 g/L |

| Dissolved in distilled water | |

Table 1: Media components.

| No. | Primers | Sequence | PCR annealing temp. (°C) | |

| 1 | tpnRL17–1RC | 5’-CGTTACATCCCTGGCTTGTT-3’ | 58.2 | |

| 2 | tpnRL13–2RC | 5’-TCGTGAAGAAGGTGTTGCTG-3’ | ||

Table 2: Primers to confirm the success of conjugation.

| Component | Volume (μL) |

| HPLC-purified water | 4.92 |

| 10x Buffer S (high specificity) | 1 |

| MgCl2 (25 mM) | 0.2 |

| dNTPs (2 mM) | 1.2 |

| Primer 1 (10 pmol/µL) | 0.8 |

| Primer 2 (10 pmol/µL) | 0.8 |

| Taq (5 U/µL) | 0.08 |

| Mastermix total | 9 |

| Template | 1 |

Table 3: PCR master mix to confirm the success of conjugation. Abbreviations: HPLC = high-performance liquid chromatography; dNTPs = deoxynucleoside triphosphate.

| Steps | Temperature °C | Time | Cycles |

| Initial Denaturation | 95 | 3 min | 1 |

| Denaturation | 95 | 40 s | |

| Annealing | 58.2 | 40 s | 30 to 35 |

| Extension | 72 | 1-2 min | |

| Final Extension | 72 | 4 min | 1 |

| Hold | 4 | ∞ | |

Table 4: PCR conditions to confirm the success of conjugation.

| Primers | Sequence | Tm °C | Use | Source | |

| Transposon-specific biotinylated primer | 5’-Biotin-ACAGGAACACTTAACGGCTGACATG -3’ | 63.5 | 6.7.1. PCR I | Custom | |

| Modified Universal PCR primer | 5’- AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATC TACACTCTTTCCCTACACGACGCTC TTCCGATCTGAATTCATCGATGAT GGTTGAGATGTGT – 3’ | 62 | 6.10.1. PCR II | Custom | |

| Index primer | Refer to the manufacturer’s manual | 6.7.1. PCR I & 6.10.1. PCR II | NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (Index primers set 1) | ||

| Adapter | Refer to the manufacturer’s manual | 6.5. Adapter ligation | NEBNext Ultra II DNA library prep kit for Illumina | ||

Table 5: Primers and adapter for PCR I and II during DNA library preparation.

| PCR mix | (µL) |

| Adapter-ligated DNA fragments | 15 |

| NEBNext Ultra II Q5 master mix | 25 |

| Index primer (10 pmol/ µL) | 5 |

| Transposon specific biotinylated primer (10 pmol/ µL) | 5 |

| Total volume | 50 |

Table 6: DNA library preparation-PCR I master mix.

| Steps | Temperature | Time | Cycles |

| Initial Denaturation | 98 °C | 30 s | 1 |

| Denaturation | 98 °C | 10 s | 6 to 12 |

| Annealing | 65 °C | 30 s | |

| Extension | 72 °C | 30 s | |

| Final Extension | 72 °C | 2 min | 1 |

| Hold | 16 °C | ∞ | |

Table 7: DNA library preparation-PCR I and II conditions.

| PCR mix | (µL) |

| Bead-selected DNA | 15 |

| NEBNext Ultra II Q5 master mix | 25 |

| Index primer | 5 |

| Modified universal PCR primer | 5 |

| Total volume | 50 |

Table 8: DNA library preparation-PCR II master mix.

| Libraries | Invivo-1 | Invivo-2 | Invivo-3 | Invitro-1 | Invitro-2 | Invitro-3 | Original library | |

| No. of reads (PE) | 56,57,710 | 39,19,051 | 30,65,849 | 35,73,494 | 28,83,440 | 36,61,956 | 46,09,410 | |

| No. of reads containing Tn – edge on 5’ end of Read-1 | 54,15,880 | 37,31,169 | 29,36,247 | 33,00,499 | 27,35,705 | 33,50,402 | 41,53,270 | |

| Bowtie2 overall alignment rate (%) (Read-1 only) | 95.53% | 83.71% | 89.87% | 80.79% | 78.00% | 73.06% | 74.92% | |

| Number of unique insertions | 8,539 | 4,134 | 7,183 | 18,930 | 18,421 | 20,438 | 24,224 | |

| Number of genes hit | 1575 | 993 | 1450 | 2793 | 2597 | 3037 | 3736 | |

Table 9: Summary of sequencing output and transposon insertion frequency per library. Abbreviation: PE = paired-end.

Discussion

A B. gladioli transposon mutant library was generated to identify important host colonization factors in the symbiotic interaction between L. villosa beetles and B. gladioli bacteria. The major steps in the protocol were conjugation, host-infection, DNA library preparation, and sequencing.

As many strains of Burkholderia are amenable to genetic modification by conjugation24,25, the plasmid carrying the transposon and antibiotic insertion cassette was conjugated successfully into the target B. gladioli Lv-StA strain from E. coli. Previous attempts of transformation by electroporation yielded very low to almost no B. gladioli transformants. It is advisable to optimize the transformation technique for the target organism to efficiently yield a large number of transformants.

One round of conjugation and 40 conjugation spots disrupted 3,736 genes in B. gladioli Lv-StA. In hindsight, multiple rounds of conjugation would be necessary to disrupt most of the 7,468 genes and obtain a saturated library. Notably, the incubation time during conjugation was not allowed to exceed 12-18 h, which is the end of the exponential growth phase of B. gladioli. Allowing conjugation beyond the exponential growth phase of bacterial cells reduces the chances of success of obtaining transconjugants26. Therefore, the conjugation period should be adjusted according to the growth of the bacterial species.

To successfully carry out an experiment involving the infection of mutant libraries in a host, it is important to assess the bacterial population bottleneck size during colonization and the diversity of mutants in the library before infection1,2,27. In preparation for the experiment, we estimated the minimum number of beetles that must be infected to have a high chance that each mutant in the library is sampled and allowed to colonize. The approximate in vivo bacterial generation time and the number of generations for the duration of the experiment were also calculated. The in vitro culture was then grown up to a comparable number of generations by adjusting the incubation time. For a similar infection experiment in other non-model hosts, the ability to maintain a laboratory culture and a constant source of the host organisms is desirable.

Following the growth of the mutant library in vivo and in vitro and sample collection, a modified DNA library preparation protocol for transposon insertion sequencing was carried out. The modification in the protocol involved designing custom PCR primers and adding PCR steps to select for DNA fragments containing the insertion cassette. Because the protocol was customized, additional PCR cycles in the protocol increased the risk of overamplification and obtaining hybridized adapter-adapter fragments in the end libraries. Hence, a final cleanup step (without size selection) after the two PCRs is recommended, as it helps in removing these fragments. The size distribution of the DNA libraries was still broader than expected. However, increasing the sequencing depth provided sufficient data that were filtered during bioinformatics analysis, obtaining satisfactory results.

As transposon-mediated mutagenesis generates thousands of random insertions in a single experiment, it is possible to generate a saturated library of mutants that contains all except those mutants where genes essential for bacterial growth have been disrupted. We most likely did not work with a saturated mutant library, given the estimations of essential genes in other studies on Burkholderia sp.28,29. A non-saturated library nevertheless helps in exploring various candidate genes for further studies using targeted mutagenesis. Before the experiments, it is also important to remember that some transposons have specific insertion target sites that increase the abundance of mutants at certain loci in the genome30. Mariner transposons are known to target AT sites for insertion31, and Tn5 transposons have a GC bias32,33. Including steps during bioinformatics analysis to recognize hotspots for transposon insertions will help in assessing any distribution bias.

Although prone to setbacks, a well-designed transposon insertion sequencing experiment can be a powerful tool to identify many conditionally important genes in bacteria within a single experiment. For example, a dozen genes in Burkholderia seminalis important for the suppression of orchid leaf necrosis were identified by combining transposon mutagenesis and genomics34. Beyond Burkholderia, several adhesion and motility genes and transporters have been identified as important colonization factors in Snodgrassella alvi symbionts of Apis mellifera (Honeybee)22, and in the Vibrio fischerii symbionts of Euprymna scolopes (Hawaiian bobtail squid)23 using the transposon-insertion mutagenesis approach.

As an alternative approach, transposon mutagenesis may be followed by screening for individual mutants using selective media instead of sequencing. Phenotypic screening or bioassays to identify deficiencies, such as motility, production of bioactive secondary metabolites, or specific auxotrophies, are feasible. For example, screening of a Burkholderia insecticola (reassigned to genus Caballeronia35) transposon mutant library has been key in identifying that the symbionts employ motility genes for colonizing Riptortus pedestris, their insect host36. Furthermore, using transposon mutagenesis and phenotypic screening, the biosynthetic gene cluster for the bioactive secondary metabolite caryoynencin was identified in Burkholderia caryophylli37. An auxotrophic mutant of Burkholderia pseudomallei was identified following transposon mutagenesis and screening and is a possible attenuated vaccine candidate against melioidosis, a dangerous disease in humans and animals38. Thus, transposon mutagenesis and sequencing is a valuable approach in studying the molecular traits of bacteria that are important for the interactions with their respective hosts in pathogenic or mutualistic associations.

Disclosures

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest pertaining to the study.

Acknowledgements

We are thankful to Junbeom Lee for providing the E. coli WM3064+pRL27 strain for conjugation and guidance in the procedure, Kathrin Hüffmeier for helping with troubleshooting during mutant library generation, and Prof. André Rodrigues for supporting insect collection and permit acquisition. We also thank Rebekka Janke and Dagmar Klebsch for support in the collection and rearing of the insects. We acknowledge the Brazilian authorities for granting the following permits for access, collection, and export of insect specimens: SISBIO authorization Nr. 45742-1, 45742-7 and 45742-10, CNPq process nº 01300.004320/2014-21 and 01300.0013848/2017-33, IBAMA Nr. 14BR016151DF and 20BR035212/DF). This research was supported by funding from the German Science Foundation (DFG) Research Grants FL1051/1-1 and KA2846/6-1.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 2,6- Diaminopimelic Acid | Alfa Aesar | B22391 | For E.coli WM3064+ pRL27 |

| Agar - Agar | Roth | 5210 | |

| Agarose | Biozym | 840004 | |

| AMPure beads XP (magentic beads + polyethylene glycol + salts) | Beckman Coulter | A63880 | Size selection in step 6.6 |

| Bleach (NaOCl) 12% | Roth | 9062 | |

| Bowtie2 v.2.4.2 | Bioinfromatic tool for read mapping. Reference 10 in main manuscript. | ||

| Buffer-S | Peqlab | PEQL01-1020 | For PCRs |

| Cell scraper | Sarstedt | 83.1830 | |

| Cutadapt v.2.10 | Bioinformatic tool for removing specific adapter sequences from the reads. Reference 8 in main manuscript. | ||

| DESeq2 | RStudio package for assessing differential mutant abundance. Usually used for RNAseq analysis. Reference 12 in main manuscript. | ||

| DNA ladder 100 bp | Roth | T834.1 | |

| dNTPs | Life Technology | R0182 | PCR for confirming success of conjugation |

| EDTA, Di-Sodium salt | Roth | 8043 | |

| Epicentre MasterPure Complete DNA and RNA Purification Kit | Lucigen | MC85200 | |

| Ethidium bromide | Roth | 2218.1 | |

| FastQC v.0.11.8 | Bioinformatic tool for assessing the quality of sequencing data. Reference 7 in main manuscript. | ||

| FeatureCounts v.2.0.1 | Bioinformatic tool to obtain read counts per genomic feature. Reference 11 in main manuscript. | ||

| Glycerol | Roth | 7530 | |

| K2HPO4 | Roth | P749 | |

| Kanamycin sulfate | Serva | 26899 | |

| KCl | Merck | 4936 | |

| KH2PO4 | Roth | 3904 | |

| MgSO4.7H2O | Roth | PO27 | |

| Na2HPO4 | Roth | P030 | |

| NaCl | Merck | 6404 | |

| NEBNext Multiplex Oligos for Illumina (Index primers set 1) | New England Biolabs | E7335S | |

| NEBNext Ultra II DNA library prep kit for Illumina | New England Biolabs | E7645S | |

| Peptone (soybean) | Roth | 2365 | For Burkholderia gladioli Lv-StA KB-medium |

| peqGOLD 'Hot' Taq- DNA Polymerase | VWR | PEQL01-1020 | PCR for confirming success of conjugation |

| Petri plates - 145 x 20 mm | Roth | XH90.1 | For selecting transconjugants |

| Petri plates - 90 x 16 mm | Roth | N221.2 | |

| Qiaxcel (StarSEQ GmbH, Germany) | Quality check after DNA library preparation | ||

| Streptavidin beads | Roth | HP57.1 | |

| Taq DNA polymerase | VWR | 01-1020 | |

| Trimmomatic v.0.36 | Bioinformatic tool for trimming low quality reads and also adapter sequences. Reference 9 in main manuscript. | ||

| Tris -HCl | Roth | 9090.1 | |

| Tryptone | Roth | 2366 | For Escherichia coli WM3064+pRL27 LB medium |

| Ultrasonicator | Bandelin | GM 70 HD | For shearing |

| USER enzyme (uracil DNA glycosylase + DNA glycosylase- lyase Endonuclease VIII) | New England Biolabs | E7645S | Ligation step 6.5.2 |

| Yeast extract | Roth | 2363 |

References

- Cain, A. K., et al. A decade of advances in transposon-insertion sequencing. Nature Reviews Genetics. 21 (9), 526-540 (2020).

- Chao, M. C., Abel, S., Davis, B. M., Waldor, M. K. The design and analysis of transposon insertion sequencing experiments. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 14 (2), 119-128 (2016).

- Barquist, L., Boinett, C. J., Cain, A. K. Approaches to querying bacterial genomes with transposon-insertion sequencing. RNA Biology. 10 (7), 1161-1169 (2013).

- Flórez, L. V., et al. Antibiotic-producing symbionts dynamically transition between plant pathogenicity and insect-defensive mutualism. Nature Communications. 8 (1), 15172 (2017).

- Flórez, L. V., Kaltenpoth, M. Symbiont dynamics and strain diversity in the defensive mutualism between Lagria beetles and Burkholderia. Environmental Microbiology. 19 (9), 3674-3688 (2017).

- Flórez, L. V., et al. An antifungal polyketide associated with horizontally acquired genes supports symbiont-mediated defense in Lagria villosa beetles. Nature Communications. 9 (1), 2478 (2018).

- . FastQC A quality control tool for high throughput sequence data Available from: https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/ (2012)

- Martin, M. Cutadapt removes adapter sequences from high-throughput sequencing reads. EMBnet.journal. 17 (1), 10-12 (2011).

- Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M., Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 30 (15), 2114-2120 (2014).

- Langmead, B., Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nature Methods. 9 (4), 357-359 (2012).

- Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K., Shi, W. FeatureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics. 30 (7), 923-930 (2014).

- Love, M. I., Huber, W., Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biology. 15 (12), 550 (2014).

- Gaytán, M. O., Martínez-Santos, V. I., Soto, E., González-Pedrajo, B. Type three secretion system in attaching and effacing pathogens. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 6, 129 (2016).

- Hachani, A., Wood, T. E., Filloux, A. Type VI secretion and anti-host effectors. Current Opinion in Microbiology. 29, 81-93 (2016).

- Deep, A., Chaudhary, U., Gupta, V. Quorum sensing and bacterial pathogenicity: From molecules to disease. Journal of Laboratory Physicians. 3 (1), 4-11 (2011).

- Silva, A. J., Benitez, J. A. Vibrio cholerae biofilms and cholera pathogenesis. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 10 (2), 0004330 (2016).

- Navarro-Garcia, F., Ruiz-Perez, F., Cataldi, &. #. 1. 9. 3. ;., Larzábal, M. Type VI secretion system in pathogenic Escherichia coli: structure, role in virulence, and acquisition. Frontiers in Microbiology. 10, 1965 (2019).

- Ribet, D., Cossart, P. How bacterial pathogens colonize their hosts and invade deeper tissues. Microbes and Infection. 17 (3), 173-183 (2015).

- Schwarz, S., et al. Burkholderia Type VI secretion systems have distinct roles in eukaryotic and bacterial cell interactions. PLoS Pathogens. 6 (8), 1001068 (2010).

- Jones, C., et al. Kill and cure: genomic phylogeny and bioactivity of Burkholderia gladioli bacteria capable of pathogenic and beneficial lifestyles. Microbial Genomics. 7 (1), 000515 (2021).

- Takeshita, K., Kikuchi, Y. Riptortuspedestris and Burkholderia symbiont: an ideal model system for insect-microbe symbiotic associations. Research in Microbiology. 168 (3), 175-187 (2017).

- Powell, J. E., et al. Genome-wide screen identifies host colonization determinants in a bacterial gut symbiont. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (48), 13887-13892 (2016).

- Brooks, J. F., et al. Global discovery of colonization determinants in the squid symbiont Vibrio fischeri. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 111 (48), 17284-17289 (2014).

- Somprasong, N., McMillan, I., Karkhoff-Schweizer, R. R., Mongkolsuk, S., Schweizer, H. P. Methods for genetic manipulation of Burkholderia gladioli pathovar cocovenenans. BMC Research Notes. 3 (308), (2010).

- Garcia, E. C. Burkholderia thailandensis: Genetic manipulation. Current Protocols in Microbiology. 45, 1-15 (2017).

- Headd, B., Bradford, S. A. The conjugation window in an Escherichia coli K-12 strain with an IncFII plasmid. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 86 (17), 00948 (2020).

- Van Opijnen, T., Camilli, A. Transposon insertion sequencing: A new tool for systems-level analysis of microorganisms. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 11 (7), 435-442 (2013).

- Gallagher, L. A., Ramage, E., Patrapuvich, R., Weiss, E., Brittnacher, M., Manoil, C. Sequence-defined transposon mutant library of Burkholderia thailandensis. mBio. 4 (6), 00604-00613 (2013).

- Wong, Y. -. C., et al. Candidate essential genes in Burkholderia cenocepacia J2315 identified by genome-wide TraDIS. Frontiers in Microbiology. 7, 1288 (2016).

- Moule, M. G., et al. Genome-wide saturation mutagenesis of Burkholderia pseudomallei K96243 predicts essential genes and novel targets for antimicrobial development. mBio. 5 (1), 00926 (2014).

- Ding, Q., Tan, K. S. Himar1 transposon for efficient random mutagenesis in Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. Frontiers in Microbiology. 8, 1842 (2017).

- Green, B., Bouchier, C., Fairhead, C., Craig, N. L., Cormack, B. P. Insertion site preference of Mu, Tn5, and Tn7 transposons. Mobile DNA. 3, 3 (2012).

- Lodge, J. K., Weston-Hafer, K., Berg, D. E. Transposon Tn5 target specificity: Preference for insertion at G/C pairs. Genetics. 120 (3), 645-650 (1988).

- Ará Ujo, W. L., et al. Genome sequencing and transposon mutagenesis of Burkholderia seminalis TC3.4.2R3 identify genes contributing to suppression of orchid necrosis caused by B. gladioli. Molecular Plant-microbe Interactions: MPMI. 29 (6), 435-446 (2016).

- Dobritsa, A. P., Samadpour, M. Reclassification of Burkholderiainsecticola as Caballeroniainsecticola comb. nov. and reliability of conserved signature indels as molecular synapomorphies. International Journal of Systematic and Evolutionary Microbiology. 69 (7), 2057-2063 (2019).

- Ohbayashi, T., et al. Insect's intestinal organ for symbiont sorting. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 112 (37), 5179-5188 (2015).

- Ross, C., Scherlach, K., Kloss, F., Hertweck, C. The molecular basis of conjugated polyyne biosynthesis in phytopathogenic bacteria. Angewandte Chemie International Edition. 53 (30), 7794-7798 (2014).

- Atkins, T., et al. A mutant of Burkholderia pseudomallei, auxotrophic in the branched chain amino acid biosynthetic pathway, is attenuated and protective in a murine model of melioidosis. Infection and Immunity. 70 (9), 5290-5294 (2002).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved