Habituation: Studying Infants Before They Can Talk

Overview

Source: Laboratories of Nicholaus Noles, Judith Danovitch, and Cara Cashon—University of Louisville

Infants are one of the purest sources of information about human thinking and learning, because they’ve had very few life experiences. Thus, researchers are interested in gathering data from infants, but as participants in experimental research, they are a challenging group to study. Unlike older children and adults, young infants are unable to reliably speak, understand speech, or even move and control their own bodies. Eating, sleeping, and looking around are the only activities babies can perform reliably. Given these limitations, researchers have developed clever techniques for exploring infants’ thoughts. One of the most popular methods makes use of a characteristic of attention called habituation.

Like adults, infants prefer to pay attention to new and interesting things. If they are left in the same environment, over time they become accustomed to their surroundings and pay less attention to them. This process is called habituation. However, the moment something new happens, infants are waiting and ready to pay attention again. This reengagement of attention following habituation is referred to as dishabituation. Scientists can use these characteristic changes in attention as a tool for studying the thinking and learning of young infants. This method involves initially presenting stimuli to infants until they are habituated, and then presenting them with different kinds of stimuli to see if they dishabituate, i.e., notice a change. By carefully choosing the stimuli shown to the infants, researchers can learn a great deal about how infants think and learn.

This experiment demonstrates how habituation can be used to study infant shape discrimination.

Procedure

Recruit a number of 6-month-old infants. Participants should be healthy, have no history of developmental disorders, and have normal hearing and vision. Because infants of this age can be uncooperative or fussy (e.g., refuse to watch a demonstration or fall asleep during testing) and will need to meet the habituation criterion, extra participants need to be recruited in order to obtain sufficient data.

1. Data collection

- Habituation Phase

- Place a chair in front of a large monitor in a quiet room.

- Instruct parents to hold their babies and remain as quiet as possible while looking at a point just above the center of the screen.

- Many studies of infant cognition require parents to be blindfolded or fitted with noise-cancelling headphones in order to make certain they don’t consciously or unconsciously influence their infant’s looking behaviors. However, having a parent wear a blindfold or headphones can alone be distracting to a baby. Therefore, some researchers simply instruct parents not to influence their babies and then review the videos after the fact to ensure that there were no issues.

- Observe the infant from another room, using a camera positioned below the monitor. This camera focuses on the infant’s face, so you can see whether the baby is looking at the monitor or away from it, not the images shown to the infant. Film the infant throughout the experiment.

- Present the stimuli in the habituation trials.

- First, an attention-getting stimulus is presented on the monitor to ensure that the infant is paying attention to the monitor prior to each trial.

- When the infant is looking at the monitor, press a key to present the stimulus assigned for habituation, in this case a blue circle.

- Simultaneously record the infant's looking time for each trial by holding down a key that tracks time. If the infant looks away from the monitor, release the key. If the baby’s attention returns to the monitor, then press the key and the stimuli remains on the screen. If the baby looks away from the monitor for more than 1.0 s at any time or looks for the maximum length of the trial (20 s), the image disappears from the screen and the attention-getting stimulus returns. This procedure is repeated for every trial throughout both phases of the experiment.

- As infants generally look longest during the first few trials of habituation and considerably less in later trials, use the first three trials in this phase to set the criteria for determining if an infant's visual attention has decreased enough to be considered habituated. In this case, this is when their average looking time on on three sequential habituation trials is 50% or less than their average looking time on the first three habituation trials observed.

- Continue this phase of the study until the infant reaches criteria for habituation. The number of trials required to reach habituation varies between babies.

- Test Phase

- Once the infant has been habituated, begin the test phase. This phase only differs from the habituation phase in that different stimuli are presented.

- Show the infant either the habituation stimulus, in this case the blue circle, or a novel stimulus—a blue square. The procedure for measuring infants' looking remains the same.

- All babies will see both stimuli: counterbalance the presentation order of the test stimuli so that half see the habituation stimulus first, while the other half see the novel stimulus first.

- Following the test trials, end the session by thanking the parent and infant for participating.

2. Analysis

- Because of the placement of the video camera, experimenters are unaware of the stimuli shown to the infant. If this is not the case, have two independent raters who are blind to the stimuli shown code the video recordings. Alternatively, many modern labs also use eye-tracking equipment that allows them to identify exactly where the infants are looking at any time during the experiment.

- Omit data from those infants who do not meet habituation criteria.

- Note the dependent variable, which is how long the infant spent looking at the novel test stimuli relative to the familiar habituated test stimulus.

Results

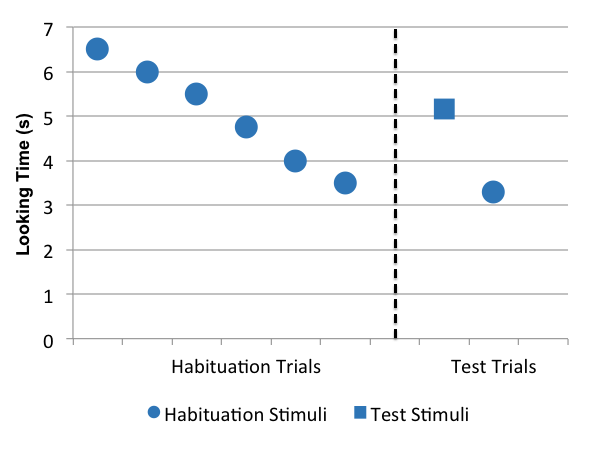

In order to have enough power to see significant results, researchers need to test at least 16 infants, not including infants dropped from the study for failing to habituate, fussiness, falling asleep, parent interference, etc.. Infants who have habituated are expected to show low levels of looking when shown the habituation stimulus during test. If infants look longer at the novel test stimulus in comparison to the habituation test stimulus after they have habituated (Figure 1), researchers would conclude that infants discriminated the stimuli. Good test stimuli are well controlled and as similar to habituation trials as possible, with the exception of the key variable being manipulated, in this case shape.

Figure 1: Average looking time across infants during habituation and test phases. The habituation stimulus is identical to the items seen during habituation, resulting in very low looking times. Infants dishabituate, or look longer, at the novel test stimulus in comparison to the habituation stimulus, if they notice the different shape.

Application and Summary

Other senses can also be tested using these same methods. For example, it is possible to measure infants’ habituation and dishabituation to auditory stimuli using pacifiers designed to measure the rate and strength of their sucking. Attentive babies suck more often and harder than babies who are habituated, so the same methods can be applied using different approaches.

Habituation methods are both powerful and limited in specific ways. When infants dishabituate, experimenters can conclude that they noticed some difference between familiar and novel test items, but it takes careful experimental design to draw conclusions from work with infants. Working with infants also creates special challenges. Most scientists do not have to worry about their participants needing a nap or diaper change during their study. However, habituation methods can be a powerful tool for studying participants unable to communicate. This approach is especially valuable to developmental scientists who are interested in studying abilities that humans are born with, as well as those that develop with very few life experiences.

Habituation methods are also used to study much more complex topics, such as the development of concepts of race, gender, and fairness. For example, by presenting infants with faces belonging to different racial groups, researchers discovered that 3-month-old babies identify new and old faces independent of race.1 However, between 6- and 9-months of age, infants undergo perceptual narrowing, after which they are more adept at recognizing individuals in their own racial group, but they find it difficult to discriminate between faces belonging to other racial groups. Thus, habituation methods represent a powerful tool for studying infant cognition and human development.

References

- Kelly, D. J., Quinn, P. C., Slater, A. M., Lee, K., Ge, L., & Pascalis, O. The other-race effect develops during infancy: Evidence of perceptual narrowing. Psychological Science. 18 (12), 1084-1089 (2007).

Skip to...

Videos from this collection:

Now Playing

Habituation: Studying Infants Before They Can Talk

Developmental Psychology

54.2K Views

Using Your Head: Measuring Infants' Rational Imitation of Actions

Developmental Psychology

10.2K Views

The Rouge Test: Searching for a Sense of Self

Developmental Psychology

54.4K Views

Numerical Cognition: More or Less

Developmental Psychology

15.1K Views

Mutual Exclusivity: How Children Learn the Meanings of Words

Developmental Psychology

33.0K Views

How Children Solve Problems Using Causal Reasoning

Developmental Psychology

13.1K Views

Metacognitive Development: How Children Estimate Their Memory

Developmental Psychology

10.5K Views

Executive Function and the Dimensional Change Card Sort Task

Developmental Psychology

15.0K Views

Categories and Inductive Inferences

Developmental Psychology

5.3K Views

The Costs and Benefits of Natural Pedagogy

Developmental Psychology

5.2K Views

Piaget's Conservation Task and the Influence of Task Demands

Developmental Psychology

61.5K Views

Children's Reliance on Artist Intentions When Identifying Pictures

Developmental Psychology

5.7K Views

Measuring Children's Trust in Testimony

Developmental Psychology

6.3K Views

Are You Smart or Hardworking? How Praise Influences Children's Motivation

Developmental Psychology

14.4K Views

Memory Development: Demonstrating How Repeated Questioning Leads to False Memories

Developmental Psychology

11.0K Views

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved