Method Article

Reconstrucción del Paleoclima Terrestre y la Paleoecología con Hojas Fósiles Utilizando la Fisionomía Digital de las Hojas y la Masa Foliar por Área

En este artículo

Resumen

El protocolo presentado muestra la medición digital y el análisis de los rasgos fisionómicos continuos de las hojas en las hojas fósiles para reconstruir el paleoclima y la paleoecología utilizando los métodos de reconstrucción de la fisionomía digital de las hojas y de la masa foliar por área.

Resumen

El clima y el medio ambiente influyen fuertemente en el tamaño, la forma y la dentadura (fisionomía) de las hojas de las plantas. Estas relaciones, particularmente en angiospermas leñosas no monocotiledóneas, se han utilizado para desarrollar proxies basados en hojas para el paleoclima y la paleoecología que se han aplicado para reconstruir ecosistemas terrestres antiguos durante los últimos ~ 120 millones de años de la historia de la Tierra. Además, dado que estas relaciones se han documentado en plantas vivas, son importantes para comprender aspectos de la evolución de las plantas y cómo las plantas responden a los cambios climáticos y ambientales. Para llevar a cabo este tipo de análisis en plantas modernas y fósiles, la fisionomía de las hojas debe medirse con precisión utilizando una metodología reproducible. Este protocolo describe un método basado en computadora para medir y analizar una variedad de variables fisionómicas foliares en hojas modernas y fósiles. Este método permite medir los rasgos fisionómicos de las hojas, en particular las variables relacionadas con las estrías de las hojas, el área de las hojas, la disección de las hojas y la linealidad que se utilizan en el proxy digital de la fisionomía de las hojas para reconstruir el paleoclima, así como el ancho del pecíolo y el área de las hojas, que se utilizan para reconstruir la masa foliar por área, un proxy paleoecológico. Debido a que este método digital de medición de rasgos foliares se puede aplicar a plantas fósiles y vivas, no se limita a aplicaciones relacionadas con la reconstrucción del paleoclima y la paleoecología. También se puede utilizar para explorar los rasgos de las hojas que pueden ser informativos para comprender la función de la morfología de las hojas, el desarrollo de las hojas, las relaciones filogenéticas de los rasgos de las hojas y la evolución de las plantas.

Introducción

Las hojas son unidades de producción fundamentales que facilitan el intercambio de energía (por ejemplo, luz, calor) y materia (por ejemplo, dióxido de carbono, vapor de agua) entre la planta y su entorno circundante 1,2. Para realizar estas funciones, las hojas deben soportar mecánicamente su propio peso contra la gravedad en aire quieto y ventoso 3,4. Debido a estos vínculos intrínsecos, varios aspectos del tamaño, la forma y la dentadura de las hojas (fisionomía) reflejan los detalles de su función y biomecánica y proporcionan información sobre su entorno y ecología. Trabajos previos han cuantificado las relaciones entre la fisionomía de las hojas, el clima y la ecología en todo el mundo moderno para establecer indicadores que se pueden aplicar a los ensamblajes de hojas fósiles 5,6. Estos indicadores brindan importantes oportunidades para reconstruir el paleoclima y la paleoecología y contribuyen a una mayor comprensión de la compleja interacción entre los diversos sistemas del planeta a lo largo de su historia. Este artículo detalla los métodos necesarios para el uso de dos proxys: 1) el método de reconstrucción de masa foliar por área para dilucidar la paleoecología, y 2) fisionomía digital de hojas para reconstruir el paleoclima.

La masa seca de hojas por área (MA) es un rasgo de la planta que se mide con frecuencia tanto en neobotánica como en paleobotánica. El valor principal de MA, especialmente para las reconstrucciones fósiles, es que es parte del espectro de la economía de la hoja, un eje coordinado de rasgos foliares bien correlacionados que incluye la tasa fotosintética de la hoja, la longevidad de la hoja y el contenido de nutrientes de la hoja en masa7. La capacidad de reconstruir MA a partir de fósiles proporciona una ventana a estos procesos metabólicos y químicos que de otro modo serían inaccesibles y, en última instancia, puede revelar información útil sobre la estrategia ecológica de las plantas y la función del ecosistema.

Royer et al.5 desarrollaron un método para estimar la MA de hojas leñosas fósiles de angiospermas no monocotiledóneas (dicotiledóneas) a partir del área de la lámina foliar y el ancho del pecíolo. Teóricamente, el pecíolo de la hoja actúa como un voladizo, sosteniendo el peso de la hoja en la posición óptima 3,4. Por lo tanto, el área de la sección transversal del pecíolo, que constituye el componente más significativo de la resistencia del haz, debe estar fuertemente correlacionada con la masa de la hoja. Al simplificar la forma del pecíolo en un tubo cilíndrico, el área de la sección transversal del pecíolo se puede representar con el ancho del pecíolo al cuadrado, lo que permite estimar la masa de la hoja a partir de un fósil bidimensional (para más detalles, ver Royer et al.5). El área foliar se puede medir directamente. En conjunto, el ancho del pecíolo al cuadrado dividido por el área de la hoja (es decir, la métrica del pecíolo; Tabla 1) proporciona un buen indicador de los fósiles de MA y permite a los paleobotánicos adentrarse en la ecología moderna basada en rasgos. Los métodos de reconstrucción MA también se han ampliadoa las gimnospermas 5,8 de hoja ancha y peciolada, a las angiospermas herbáceas8 y a los helechos9, que produjeron relaciones que difieren de las relaciones observadas para las angiospermas dicotiledóneas leñosas y entre sí. Un conjunto de datos ampliados de dicotiledóneas leñosas y nuevas ecuaciones de regresión para reconstruir la varianza y la media de MA a nivel de sitio permiten inferir la diversidad de estrategias económicas foliares y qué estrategias son las más prevalentes entre las angiospermas dicotiledóneas leñosas en floras fósiles10.

La relación entre los rasgos fisionómicos de las hojas y su clima se ha observado desde hace más de un siglo11,12. Específicamente, la fisonomía de las hojas leñosas de angiospermas dicotiledóneas está fuertemente correlacionada con la temperatura y la humedad13. Esta relación ha formado la base para numerosos proxies fisionómicos de hojas univariados 14,15,16,17 y multivariados 6,18,19,20,21,22 para el paleoclima terrestre. Los métodos paleoclimáticos fisionómicos de hojas, tanto univariados como multivariados, se han aplicado ampliamente a las floras fósiles dominadas por angiospermas en todos los continentes, abarcando los últimos ~ 120 millones de años de la historia de la Tierra (Cretácico a moderno)23.

Dos observaciones fundamentales utilizadas en los indicadores fisionómicos del paleoclima foliar son: 1) la relación entre el tamaño de la hoja y la precipitación media anual (MAP) y 2) la relación entre los dientes de la hoja (es decir, las proyecciones hacia el exterior del margen de la hoja) y la temperatura media anual (MAT). Específicamente, el tamaño promedio de las hojas de todas las especies de angiospermas dicotiledóneas leñosas en una localidad se correlaciona positivamente con MAP, y la proporción de especies de angiospermas dicotiledóneas leñosas en una localidad con hojas dentadas, además del tamaño y número de dientes se correlaciona negativamente con MAT 6,12,13,14,15,16,24.

Un vínculo funcional entre estas relaciones entre la fisionomía de las hojas y el clima está fuertemente respaldado tanto por la teoría como por la observación 1,2,25. Por ejemplo, aunque las hojas más grandes proporcionan una mayor superficie fotosintética, requieren un mayor soporte, pierden más agua a través de la transpiración y retienen más calor sensible debido a una capa límite más gruesa 1,26,27. Por lo tanto, las hojas más grandes son más comunes en ambientes más húmedos y cálidos porque la pérdida de agua a través del aumento de la transpiración enfría efectivamente las hojas y es menos problemática. Por el contrario, las hojas más pequeñas en climas cálidos más secos reducen la pérdida de agua y evitan el sobrecalentamiento al aumentar la pérdida de calor sensible28,29. Los detalles de qué factores, o combinación de factores, contribuyen más fuertemente a explicar los vínculos funcionales siguen siendo enigmáticos para otros rasgos de las hojas. Por ejemplo, se han propuesto varias hipótesis para explicar la relación entre los dientes de la hoja y el MAT, incluyendo el enfriamiento de las hojas, el empaquetamiento eficiente de las yemas, la mejora del soporte y el suministro de hojas delgadas, la gutación a través de los hidatodos y el aumento de la productividad a principios de la temporada 30,31,32,33.

La mayoría de los indicadores fisionómicos del paleoclima foliar se basan en la división categórica de los rasgos de las hojas en lugar de en mediciones cuantitativas de variables continuas, lo que lleva a varias deficiencias potenciales. El enfoque categórico excluye la incorporación de información más detallada capturada por mediciones continuas que están fuertemente correlacionadas con el clima (por ejemplo, número de dientes, linealidad de las hojas), lo que puede reducir la precisión de las estimaciones paleoclimáticas 6,20,34. Además, en algunos de los métodos de puntuación de rasgos foliares, los rasgos que se puntúan categóricamente pueden ser ambiguos, lo que genera problemas de reproducibilidad, y algunos rasgos tienen evidencia empírica limitada para respaldar su vínculo funcional con el clima 6,15,16,35,36.

Para abordar estas deficiencias, Huff et al.20 propusieron medir digitalmente los rasgos continuos de las hojas en un método conocido como fisionomía digital de las hojas (DiLP). Una ventaja clave de DiLP sobre los métodos anteriores es su dependencia de rasgos que 1) se pueden medir de manera confiable entre los usuarios, 2) son de naturaleza continua, 3) están funcionalmente vinculados al clima y 4) muestran plasticidad fenotípica entre las estaciones de crecimiento 6,37. Esto ha llevado a estimaciones más precisas de MAT y MAP que los métodos paleoclimáticos fisionómicos foliaresanteriores 6. Además, el método se adapta a la naturaleza imperfecta del registro fósil al proporcionar pasos para dar cuenta de las hojas dañadas e incompletas. El método DiLP se ha aplicado con éxito a una variedad de floras fósiles de múltiples continentes que abarcan un amplio rango de tiempo geológico 6,38,39,40,41,42.

El siguiente protocolo es una expansión del descrito en el trabajo anterior 5,6,20,34. Se explicarán los procedimientos necesarios para reconstruir el paleoclima y la paleoecología a partir de hojas fósiles de angiospermas dicotiledóneas leñosas utilizando los métodos de reconstrucción DiLP y MA (ver Tabla 1 para una explicación de las variables medidas y calculadas mediante el uso de este protocolo). Además, este protocolo proporciona pasos para registrar y calcular los rasgos foliares no incluidos en el análisis DiLP o MA, pero que son fáciles de implementar y proporcionan caracterizaciones útiles de la fisionomía foliar (Tabla 1). El protocolo sigue el siguiente formato: 1) Obtención de imágenes de hojas fósiles; 2) preparación digital de hojas, organizada en cinco posibles escenarios de preparación; 3) medición digital de hojas, organizada en los mismos cinco escenarios de preparación posibles; y 4) análisis DiLP y MA, utilizando el paquete R dilp10.

El protocolo para las reconstrucciones de MA está integrado en el protocolo DiLP porque ambos son convenientes de preparar y medir uno al lado del otro. Si un usuario está interesado solo en los análisis de MA , debe seguir los pasos de preparación descritos en el escenario de preparación 2 de DiLP, ya sea que el margen de la hoja esté dentado o no, y los pasos de medición que describen solo el ancho del pecíolo, el área del pecíolo y las mediciones del área de la hoja. A continuación, un usuario puede ejecutar las funciones adecuadas en el paquete dilp R que realiza las reconstrucciones MA .

Protocolo

1. Imágenes de hojas fósiles

- Coloque el fósil de hoja debajo de la cámara y asegúrese de que esté lo más plano posible usando, por ejemplo, una caja de arena o masilla para colocar debajo del fósil.

NOTA: Al fotografiar varios especímenes en un solo bloque, es mejor fotografiarlos como primeros planos por separado para garantizar que los detalles del fósil sean claros y nítidos. También es útil colocar el fósil sobre un fondo mate oscuro sólido, como fieltro negro o terciopelo. - Coloca una barra de escala horizontalmente y en el mismo plano vertical que la hoja, colocándola cerca del fósil pero sin cubrir ninguna parte de él. Si hay poca o ninguna matriz alrededor del fósil, la escala debe colocarse dentro del marco de la foto y estar enfocada.

- Usando un trípode de cámara o un soporte para copias, coloque la cámara directamente sobre la hoja fósil con la lente paralela a la superficie de la roca. Para asegurarse de que los detalles de la hoja se capturen con nitidez, coloque la cámara lo más cerca posible del fósil mientras se mantiene dentro de la distancia focal de la lente/cámara y se asegura de que todo el fósil esté dentro del marco de la fotografía.

NOTA: Si es posible, es mejor utilizar una cámara digital de alta resolución y una lente macro con enfoque manual y suficiente profundidad de campo para enfocar nítidamente la hoja que se procesará. - Usando luz indirecta, ilumina el fósil según sea necesario para ver claramente todo el contorno del espécimen. A menudo es necesario reajustar la iluminación de cada fósil.

- Fotografíe la hoja fósil y etiquete el archivo de imagen de manera adecuada.

2. Preparación digital

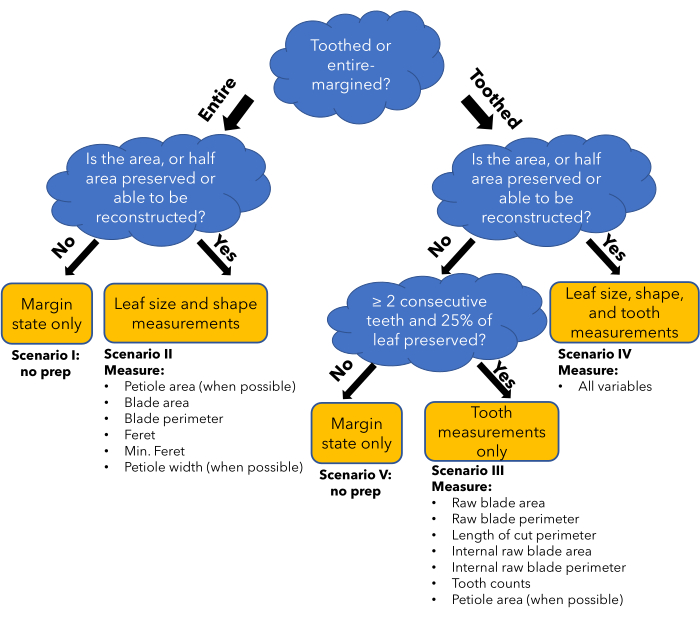

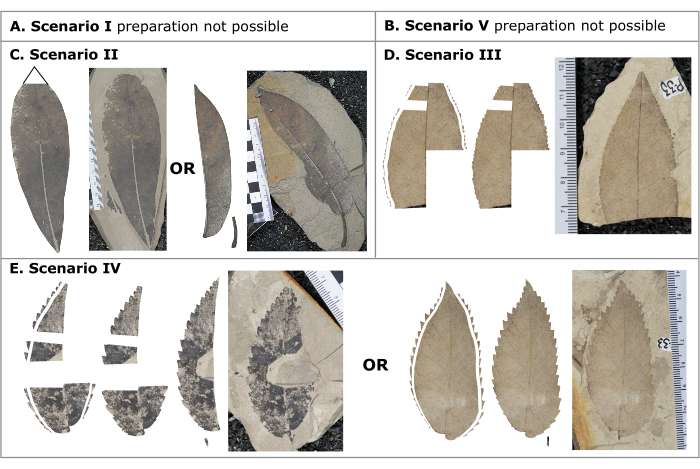

NOTA: En la Figura 1 se proporciona una ilustración de la terminología arquitectónica de la hoja utilizada en estos protocolos. Utilice el árbol de decisión (Figura 2) y los ejemplos proporcionados (Figura 3) para determinar qué escenario de preparación es aplicable a la hoja fósil que se va a medir y proceda a esa sección apropiada. Consulte la Tabla 2 para obtener consideraciones adicionales en los pasos de preparación. Si la hoja se encuentra en el escenario 1 o 5, la hoja no se puede preparar para las mediciones cuantitativas de la fisionomía foliar.

- Escenario 2: Hoja entera con márgenes cuya área, o la mitad del área, se conserva o se puede reconstruir.

- Abra el archivo en el software de procesamiento de imágenes (por ejemplo, Adobe Photoshop o GIMP). Recorte la imagen, si es necesario, lo que ayuda a reducir el tamaño final del archivo, pero garantiza que la barra de escala siga estando incluida.

- Duplique el ancho del área de trabajo haciendo clic en Imagen > lienzo (Photoshop); Tamaño de la imagen > lienzo (GIMP). Se sugiere agregar un nuevo lienzo a la derecha o a la izquierda del lienzo actual.

- Si el margen de la hoja requiere alguna reconstrucción, decida si el área y la forma de la hoja se pueden medir de manera más confiable a partir de una media hoja o de una hoja entera (Figura 3).

- Copia la hoja de la matriz de roca. Traza la hoja entera o la mitad, incluyendo el pecíolo si está presente, usando una herramienta de lazo (ver Tabla 2). Copie y pegue la selección y colóquela en un área abierta del lienzo. Considere la posibilidad de pegar dos copias de esta selección, una de las cuales es una copia sin editar para volver a ella si es necesario para reiniciar el proceso de preparación.

- Repare las partes dañadas del margen usando una línea de color apropiado (generalmente negro si está sobre un fondo blanco). Dibuje una línea que abarque el margen dañado para que el margen se reconstruya de forma fiable, utilizando, por ejemplo, la herramienta de pincel o línea. Asegúrese de que la línea sea lo suficientemente gruesa como para ser vista (~1-2 pt de peso) y que conecte el margen a través del área dañada.

- Retire el pecíolo de la hoja, si está presente, con la herramienta de lazo.

- Visualmente, siga el margen de la hoja a lo largo de la base hasta el punto en que entra en contacto con el pecíolo, que suele ser de color más oscuro y no contiene venas distintivas. Coloca un punto de lazo allí. Haz lo mismo en la otra mitad de la hoja y coloca el segundo punto allí.

NOTA: Si la base de la hoja es simétrica, la línea será ~perpendicular al pecíolo; Si es asimétrica, la línea estará en ángulo. - Rodea todo el pecíolo para terminar la selección. Corta y pega, o usa la herramienta de movimiento, para colocar el pecíolo junto a la hoja de la hoja, pero sin tocarla.

NOTA: Para una base de hoja cordada o lobulada, lo que significa que la base se extiende por debajo de donde el pecíolo se une a la lámina de la hoja, el pecíolo tiene el potencial de descansar sobre la base de la hoja por debajo de donde el pecíolo se une a la lámina de la hoja. Tenga cuidado de cortar el pecíolo donde realmente se une, trace el margen del pecíolo de cerca y repare el margen dañado resultante. Se reconoce que esto puede ser difícil de ver en la mayoría de los fósiles.

- Visualmente, siga el margen de la hoja a lo largo de la base hasta el punto en que entra en contacto con el pecíolo, que suele ser de color más oscuro y no contiene venas distintivas. Coloca un punto de lazo allí. Haz lo mismo en la otra mitad de la hoja y coloca el segundo punto allí.

- Recorte el área final de la imagen si es necesario para reducir el tamaño del archivo. Consulte la Figura 3 para ver un ejemplo de cómo debe aparecer la imagen preparada completa.

- Escenario 3: una hoja dentada cuya área, o media área, no se puede reconstruir, pero tiene ≥ dos dientes consecutivos y el ≥25% de la hoja conservada

NOTA: Las medidas de los dientes son los únicos rasgos que se pueden medir en las hojas de esta categoría, por lo que las hojas están preparadas solo para estas mediciones.- Abra el archivo en un software de procesamiento de imágenes (por ejemplo, Adobe Photoshop o GIMP). Recorte la imagen, si es necesario, lo que ayuda a reducir el tamaño final del archivo, pero asegúrese de que la barra de escala aún esté incluida.

- Tripe para cuadruplicar el ancho del área de trabajo haciendo clic en Imagen > lienzo (Photoshop); Tamaño de la imagen > lienzo (GIMP). Se sugiere agregar un nuevo lienzo a la derecha o a la izquierda del lienzo actual.

- Copia la hoja de la matriz de roca. Traza la extensión de la hoja preservada, incluido el pecíolo si está presente, con una herramienta de lazo. No se preocupe por trazar las partes dañadas del margen precisamente porque se eliminarán. Copie y pegue la selección y colóquela en un área abierta del lienzo. Considere la posibilidad de pegar dos copias de esta selección, una de las cuales es una versión sin editar para volver a ella si es necesario reiniciar el proceso de preparación.

- Si está presente, retire el pecíolo de la hoja con la herramienta de uso de lazo.

- Visualmente, siga el margen de la hoja a lo largo de la base hasta el punto en que entra en contacto con el pecíolo, que suele ser de color más oscuro y no contiene venas distintivas. Coloca un punto de lazo allí. Haz lo mismo en la otra mitad de la hoja y coloca el segundo punto allí.

NOTA: Si la base de la hoja es simétrica, la línea será ~perpendicular al pecíolo, si es asimétrica, la línea estará en ángulo. - Rodea todo el pecíolo para terminar la selección. Corta y pega, o usa la herramienta de movimiento, para colocar el pecíolo junto a la hoja de la hoja, pero sin tocarla.

NOTA: Para una base de hoja cordada o lobulada, lo que significa que la base se extiende por debajo de donde el pecíolo se une a la lámina de la hoja, el pecíolo tiene el potencial de descansar sobre la base de la hoja por debajo de donde el pecíolo se une a la lámina de la hoja. Tenga cuidado de cortar el pecíolo donde realmente se une, trace el margen del pecíolo de cerca y repare el margen dañado resultante. Esto puede ser difícil de ver en la mayoría de los fósiles.

- Visualmente, siga el margen de la hoja a lo largo de la base hasta el punto en que entra en contacto con el pecíolo, que suele ser de color más oscuro y no contiene venas distintivas. Coloca un punto de lazo allí. Haz lo mismo en la otra mitad de la hoja y coloca el segundo punto allí.

- Elimine el área adyacente a las partes dañadas del margen con una herramienta de lazo.

- Comience la selección en un punto a lo largo del margen que limite la parte dañada y trace una línea recta desde ese punto hasta la vena principal que sea perpendicular a esa vena principal (Figura 4). Comience la selección en el seno dental primario preservado más cercano al daño. Esto asegura que el flanco de un diente no se incluya como perímetro interno en las mediciones posteriores, y que los dientes subsidiarios no se midan como si fueran dientes primarios. Esto puede no ser apropiado si los dientes están espaciados a distancia, ya que se puede terminar eliminando demasiado margen conservado (Figura 4).

- Proceda a la selección a lo largo de la vena principal hasta que esté al nivel del otro límite del margen dañado y trace una línea recta perpendicular a la vena mayor al margen (Figura 4).

NOTA: Para las hojas pinnadas (Figura 1A), con y sin venas agrofáficas (ver Ellis et al.43), la vena principal es la vena primaria (es decir, la vena media). En el caso de las hojas palmeadas con nervaduras (Figura 1B, D), la vena principal es la vena primaria más cercana (p. ej., Figura 4B). En el caso de las hojas pinnadas lobuladas (Figura 1C), si el daño se localiza en un lóbulo pinnado, la vena principal es la vena (típicamente una vena secundaria) que alimenta el lóbulo. - Complete la selección y elimine esta parte de la hoja. Repita para todas las partes dañadas de la hoja.

- Copia y pega esta hoja preparada y colócala en un área abierta del lienzo.

- Retira los dientes con una herramienta de lazo.

- Comience en el ápice de la hoja, uno de los ápices del lóbulo o el diente más apical de un fragmento de hoja, y haga una selección en cada seno del diente primario a lo largo de esa hoja, lóbulo o fragmento (Figura 5; consulte la Figura complementaria 1, la Figura complementaria 2 para obtener consejos sobre cómo distinguir los dientes primarios y subsidiarios y cómo distinguir los dientes de los lóbulos). Asegúrese de seguir las reglas apropiadas al cortar los dientes (Tabla 2; Figura complementaria 3).

NOTA: Los dientes primarios a menudo se vuelven más pequeños hacia la base y el ápice. - Después de seleccionar el seno apical del diente más basal, aplicar la regla de extensión (Tabla 2; Figura complementaria 4) para cortar el último diente de la secuencia.

- Retire los dientes cortando y pegando los dientes junto a la lámina de la hoja con los dientes extraídos sin tocarla. Si la preparación tiene lóbulos o fragmentos de hojas adicionales que requieren que se extraigan los dientes, repita los pasos anteriores hasta que se extraigan todos los dientes.

- Comience en el ápice de la hoja, uno de los ápices del lóbulo o el diente más apical de un fragmento de hoja, y haga una selección en cada seno del diente primario a lo largo de esa hoja, lóbulo o fragmento (Figura 5; consulte la Figura complementaria 1, la Figura complementaria 2 para obtener consejos sobre cómo distinguir los dientes primarios y subsidiarios y cómo distinguir los dientes de los lóbulos). Asegúrese de seguir las reglas apropiadas al cortar los dientes (Tabla 2; Figura complementaria 3).

- Si se creó una versión adicional de la hoja recortada original, elimine la versión adicional. Recorte el área final de la imagen si es necesario para reducir el tamaño del archivo. Consulte la Figura 3 para ver un ejemplo de cómo debe aparecer la imagen preparada completa.

- Escenario 4: una hoja dentada cuya área, o área foliar, se conserva o se puede reconstruir

- Abra el archivo en el software de procesamiento de imágenes (por ejemplo, Adobe Photoshop o GIMP). Recorte la imagen, si es necesario, lo que ayuda a reducir el tamaño final del archivo, pero asegúrese de que la barra de escala aún esté incluida.

- Tripe para cuadruplicar el ancho del área de trabajo haciendo clic en Imagen > lienzo (Photoshop); Tamaño de la imagen > lienzo (GIMP). Se sugiere agregar un nuevo lienzo a la derecha o a la izquierda del lienzo actual.

- Decide cómo se preparará la hoja. Las mediciones del área/forma de la hoja deben realizarse en una hoja entera o en la mitad de la hoja, decida qué opción dará como resultado mediciones más precisas. Las mediciones de los dientes deben realizarse a lo largo de todas las secciones del margen conservado. En algunos casos, las mediciones del área/forma de la hoja pueden ocurrir en un subconjunto diferente de la hoja que el subconjunto donde se miden las variables de los dientes.

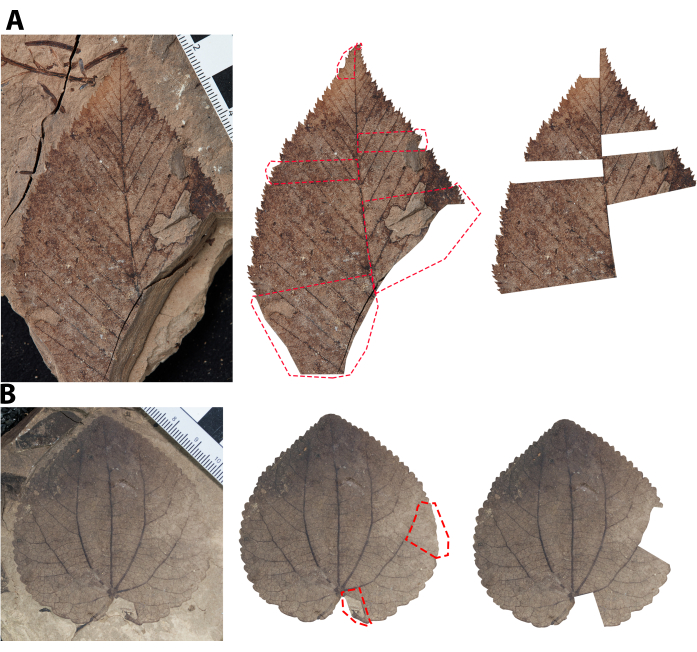

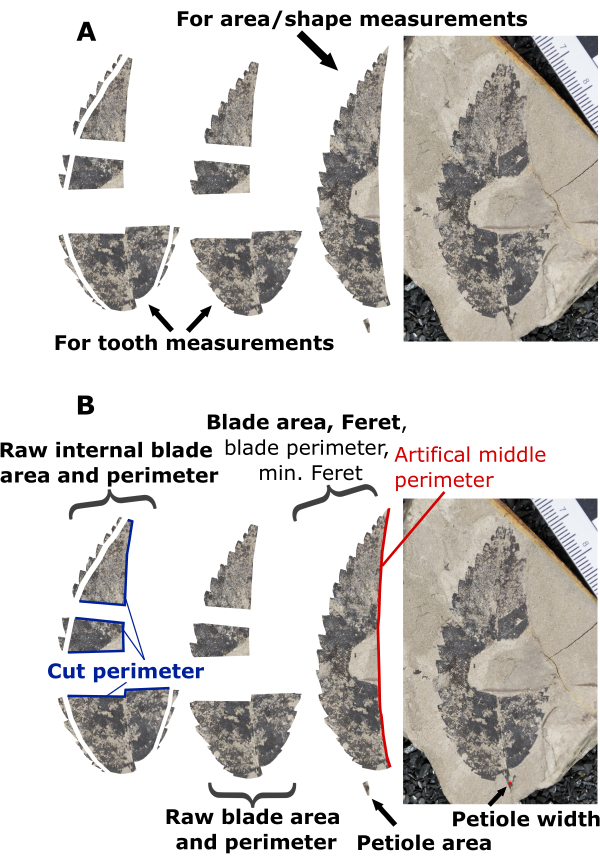

NOTA: En el ejemplo proporcionado (Figura 6), se decidió que una media hoja se reconstruiría de manera más confiable que una hoja entera. Se incluyó el margen preservado en la parte inferior derecha (>1 diente preservado) para las medidas de los dientes. El siguiente protocolo para el Escenario 4 sigue aproximadamente el ejemplo proporcionado (Figura 6), pero los detalles pueden variar ligeramente en diferentes contextos de preparación. - Copie la hoja de la matriz de roca, asegurándose de incluir todo el margen conservado.

- Traza el margen de la hoja, incluido el pecíolo si está presente, con una herramienta de lazo. No trace las partes dañadas del margen que no se incluirán en las mediciones de área/forma precisamente porque se eliminarán (por ejemplo, la mitad derecha de la hoja en la Figura 6).

- Copie y pegue la selección y colóquela en un área abierta del lienzo. Considere la posibilidad de pegar dos copias de esta selección, una de las cuales es una copia sin editar para volver a ella si es necesario para reiniciar el proceso de preparación.

- Si está presente, retire el pecíolo de la hoja con la herramienta Lazo.

- Visualmente, siga el margen de la hoja a lo largo de la base hasta el punto en que entra en contacto con el pecíolo, que suele ser de color más oscuro y no contiene venas distintivas. Coloca un punto de lazo allí. Haz lo mismo en la otra mitad de la hoja y coloca el segundo punto allí.

NOTA: Si la base de la hoja es simétrica, la línea será ~perpendicular al pecíolo; Si es asimétrica, la línea estará en ángulo. Rodea todo el pecíolo para terminar la selección. - Corta y pega, o usa la herramienta de movimiento, para colocar el pecíolo junto a la hoja, pero sin tocarla.

NOTA: Para una base de hoja cordada o lobulada, lo que significa que la base se extiende por debajo de donde el pecíolo se une a la lámina de la hoja, el pecíolo tiene el potencial de descansar sobre la base de la hoja por debajo de donde el pecíolo se une a la lámina de la hoja. Tenga cuidado de cortar el pecíolo donde se une, trace el margen del pecíolo de cerca y repare el margen dañado resultante (Figura complementaria 5). Esto puede ser difícil de ver en la mayoría de los fósiles.

- Visualmente, siga el margen de la hoja a lo largo de la base hasta el punto en que entra en contacto con el pecíolo, que suele ser de color más oscuro y no contiene venas distintivas. Coloca un punto de lazo allí. Haz lo mismo en la otra mitad de la hoja y coloca el segundo punto allí.

- Copia y pega la hoja aislada sin el pecíolo para crear una segunda copia para prepararla para las medidas de los dientes y colócala en un área abierta del lienzo.

- Prepare una versión de la hoja para las mediciones del área y la forma de la hoja.

- Si preparas una media hoja, recorta el exceso de material de la hoja con la herramienta de lazo para que solo quede una media hoja completa. Si prepara una hoja completa, no retire ningún material de hoja.

- Si es necesario, repare las áreas dañadas a lo largo del margen con una línea de color apropiado con una herramienta de línea o pincel (por lo general, una línea negra para un fondo blanco). Asegúrese de que la línea sea lo suficientemente gruesa como para ser vista (~1-2 pt de peso) y que conecte el margen a través del área dañada.

- Prepare una versión de la hoja para las medidas de los dientes.

- Elimine el área adyacente a las partes dañadas del margen con una herramienta de lazo.

- Comience la selección en un punto a lo largo del margen que limite la parte dañada y trace una línea recta desde ese punto hasta la vena principal que es perpendicular a esa vena principal (Figura 4). Comience la selección en el seno dental primario preservado más cercano al daño. Esto asegura que el flanco de un diente no se incluya como perímetro interno en las mediciones posteriores, y que los dientes subsidiarios no se midan como si fueran dientes primarios. Esto puede no ser apropiado si los dientes están espaciados a distancia, ya que se puede terminar eliminando demasiado margen conservado (Figura 4).

- Proceda a la selección a lo largo de la vena principal hasta que esté al nivel del otro límite del margen dañado y trace una línea recta perpendicular a la vena principal al margen (Figura 4).

NOTA: Para las hojas pinnadas (Figura 1A), con y sin venas agrofáficas (ver Ellis et al.43 para definición y ejemplos), la vena principal es la vena primaria (es decir, la vena media). En el caso de las hojas palmeadas con nervaduras (Figura 1B, D), la vena principal es la vena primaria más cercana (p. ej., Figura 4B). En el caso de las hojas pinnadas lobuladas (Figura 1C), si el daño se localiza en un lóbulo pinnado, la vena principal es la vena (típicamente una vena secundaria) que alimenta el lóbulo. - Elimina la parte dañada de la hoja. Haz lo mismo con todas las partes dañadas de la hoja.

- Elimine el área adyacente a las partes dañadas del margen con una herramienta de lazo.

- Copie y pegue la versión preparada para las mediciones de dientes, sin las partes dañadas, y colóquela en un área abierta del lienzo.

- Retira los dientes con una herramienta de lazo.

- Comience en el ápice de la hoja, uno de los ápices del lóbulo, o el diente más apical de un fragmento de hoja, y haga una selección en cada seno del diente primario a lo largo de la hoja, el lóbulo o el fragmento (Figura 5; consulte la Figura complementaria 2 para obtener consejos sobre cómo distinguir los dientes primarios y subsidiarios y cómo distinguir los dientes de los lóbulos). Asegúrese de seguir las reglas apropiadas al cortar los dientes (Tabla 2; Figura complementaria 2).

NOTA: Los dientes primarios a menudo se vuelven más pequeños hacia la base y el ápice. - Después de seleccionar el seno apical del diente más basal, aplicar la regla de extensión (Tabla 2; Figura complementaria 4) para cortar el último diente de la secuencia.

- Retire los dientes cortando y pegando los dientes junto a la lámina de la hoja con los dientes extraídos sin tocarla. Si la preparación tiene lóbulos o fragmentos de hojas adicionales que requieren que se extraigan los dientes, repita los pasos anteriores hasta que se extraigan todos los dientes.

- Comience en el ápice de la hoja, uno de los ápices del lóbulo, o el diente más apical de un fragmento de hoja, y haga una selección en cada seno del diente primario a lo largo de la hoja, el lóbulo o el fragmento (Figura 5; consulte la Figura complementaria 2 para obtener consejos sobre cómo distinguir los dientes primarios y subsidiarios y cómo distinguir los dientes de los lóbulos). Asegúrese de seguir las reglas apropiadas al cortar los dientes (Tabla 2; Figura complementaria 2).

- Si se creó una versión adicional de la hoja recortada original, elimine la versión adicional. Recorte el área final de la imagen si es necesario para reducir el tamaño del archivo. Consulte la Figura 3 para ver un ejemplo de cómo debe aparecer la imagen preparada completa.

3. Medición digital

NOTA: Se proporciona una hoja de cálculo de plantilla de entrada de datos como Archivo Complementario 1. Consulte la Tabla 3 para obtener consideraciones adicionales en los pasos de medición. En los escenarios 1 y 5, el único paso necesario es registrar el estado del margen de la hoja en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos (paso 3.5).

- Abra el software ImageJ44. Establezca qué mediciones se realizarán automáticamente (haga esto una vez después de instalar el programa).

- Haga clic en Analizar > Establecer medidas y seleccione solo el Área, el Perímetro y el diámetro de Feret. Asegúrese de que los decimales estén configurados en 3.

- Abra la imagen de la hoja fósil preparada haciendo clic en Archivo > Abrir o simplemente arrastrando y soltando la imagen en la barra de herramientas de ImageJ ya abierta.

- Establezca la escala para cada nueva imagen de hoja.

NOTA: Este es un paso crítico y debe realizarse para cada nueva imagen de hoja para garantizar mediciones precisas.- Haga clic en la herramienta Línea recta. Acércate a la barra de escala y dibuja la línea recta más larga posible a través de la barra de escala.

- Haga clic en Analizar > Establecer escala. En distancia conocida, introduzca la longitud medida en cm (para que coincida con la unidad utilizada en el conjunto de datos de calibración moderno). No es necesario cambiar la unidad de longitud. Haga clic en Aceptar.

- Marque la hoja como dentada (0) o entera (1) en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos.

- Mida el ancho del pecíolo si el pecíolo está presente. Las mediciones deben realizarse en la copia original de la hoja que aún se encuentra en la matriz de roca, ya que proporciona un contexto mucho mejor.

NOTA: Si el pecíolo no está presente, en algunos casos, se puede medir el ancho de la vena media en su posición basrelativa en lugar del pecíolo. Sin embargo, esto solo debe hacerse si se conserva todo el ancho de la vena media (es decir, no hay lámina comprimida sobre la vena o el fósil conserva el lado abaxial de la hoja) y otros especímenes de la misma especie o morfotipo muestran que el ancho de la vena basal es equivalente al ancho del pecíolo.- Dibuje una línea recta perpendicular al pecíolo, donde el pecíolo se encuentra con la lámina de la hoja, o si el punto de inserción es asimétrico, dibuje una línea perpendicular al pecíolo en el punto más basal de inserción. Es importante trazar esta línea con cuidado. Por lo tanto, se recomienda acercar esta área de la hoja para que sea más fácil dibujar la línea con precisión.

NOTA: Existen circunstancias especiales en las que es necesario modificar este paso, incluso si, en el punto más basal de inserción, existen daños, tricomas, nectarios, espinas u otras características que impidan mediciones precisas del ancho del pecíolo. En estos casos, mida el ancho del pecíolo en el primer punto por debajo de la característica donde se pueda realizar la medición de manera confiable. - Haga clic en Analizar > medir o utilice un método abreviado para medir la longitud de la línea dibujada. Dibuje la misma línea en la imagen para crear un registro de exactamente dónde se realizó la medición haciendo clic en Editar > Dibujar o utilizando un acceso directo. Cambie el color de la línea usando una herramienta en la barra de herramientas principal (selector de color), si es necesario.

- Una vez dibujada la línea, guarde la imagen, preferiblemente con un nombre de archivo modificado.

- Registre la longitud de esta línea bajo el ancho del pecíolo en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos.

- Dibuje una línea recta perpendicular al pecíolo, donde el pecíolo se encuentra con la lámina de la hoja, o si el punto de inserción es asimétrico, dibuje una línea perpendicular al pecíolo en el punto más basal de inserción. Es importante trazar esta línea con cuidado. Por lo tanto, se recomienda acercar esta área de la hoja para que sea más fácil dibujar la línea con precisión.

- Prepare la hoja para medidas adicionales haciendo que la imagen sea en blanco y negro. Para ello, haga clic en Imagen > Escriba > 8 bits.

- Umbral de la imagen haciendo clic en Imagen > Ajustar > Umbral o utilice el acceso directo. Se abrirá un cuadro titulado Umbral y cambiará parte de la imagen a rojo. Si la hoja es de color claro y el fondo es oscuro, haga clic en Fondo oscuro.

- Ajuste el umbral con la barra deslizante hasta que el interior de la hoja sea rojo y se distinga del fondo. Este es un paso crítico y un lugar fácil para producir datos imprecisos. Asegúrese de que el área roja corresponda exactamente a la hoja (es decir, todo el perímetro de la hoja sea rojo y no más), acercándose a algunas secciones del margen. Los espacios rojos dentro del interior de la hoja son aceptables y no afectan las mediciones.

NOTA: Si el contorno de la hoja no está bien definido, primero intente ajustar el umbral mientras se acerca para confirmar que el contorno de la hoja es rojo. Si el contraste deficiente entre el fósil y el fondo impide que se aplique un umbral confiable, use la herramienta de pincel para agregar un contorno sólido al perímetro de la hoja en áreas donde el contraste es demasiado pobre. Alternativamente, devuelva la hoja al software de procesamiento de imágenes (por ejemplo, Adobe Photoshop o GIMP) y ajuste el contraste de las capas de hojas aisladas o el color del fondo para diferenciarlas mejor. - Mida el área y la forma de las hojas preparadas en los escenarios 2 (paso 2.1) y 4 (paso 2.4).

NOTA: Utilice la Figura 2 y la Figura 6B como guía para determinar qué variables se miden en qué componentes de la imagen preparada. Si las hojas se prepararon en el escenario 3 (paso 2.2), omita este paso y continúe con el paso 3.11.- Mida la hoja preparada para las mediciones de área y forma de la hoja, a la que solo se le debe quitar el pecíolo (si había un pecíolo presente). Seleccione la herramienta Varita . Haga clic en el interior de la hoja. Toda la hoja debe estar delineada en amarillo, confirme que el contorno sea correcto.

- Realice mediciones haciendo clic en Analizar > medir o utilizando el acceso directo.

- Si el área medida se prepara como una hoja entera, registre el área, el perímetro, el Feret y el Feret mínimo en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos. Si el área medida se prepara como media hoja, solo registre Feret y continúe con el siguiente paso.

- Si el área medida es de media hoja, mida el perímetro medio artificial de la hoja, que es la longitud del perímetro artificial que resulta de cortar la hoja por la mitad (Figura 6B). Si el área medida es toda la hoja, omita este paso y el paso 3.10.5.

NOTA: La medición del perímetro medio artificial permite calcular el perímetro de la hoja a partir de medias hojas (consulte el paso 3.10.5 a continuación). El perímetro de la hoja no se utiliza en las variables incluidas en los análisis DiLP y MA , pero se utiliza para otras variables útiles para la caracterización de la fisionomía (por ejemplo, factor de forma, compacidad; Tabla 1).- Seleccione la herramienta de línea segmentada haciendo clic con el botón derecho en la herramienta Línea . Traza toda la longitud del perímetro central artificial.

- Haga clic en Analizar > medir o utilice el acceso directo para medir la longitud. Esta medida se utilizará en la fórmula para calcular el perímetro de la hoja a continuación (paso 3.10.5).

- Si el área medida es de media hoja, modifique las medidas a medida que las introduzca en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos multiplicando el área por 2, multiplicando el Feret mínimo por 2 y calculando el perímetro de la hoja restando primero el perímetro central artificial del perímetro de la mitad de la hoja y, a continuación, multiplicando por 2 mediante la siguiente fórmula:

Perímetro de la hoja = (perímetro - perímetro medio artificial) x 2 - Si hay un pecíolo recortado, mida su área. Si no está presente, la medición se completa para el escenario 2, pero continúe con el paso 3.11 para el escenario 4.

- Haga clic en el pecíolo recortado con la herramienta de varita. El pecíolo debe estar delineado en amarillo. Realice mediciones haciendo clic en Analizar > medir o utilizando el acceso directo. Registre el área debajo del área del pecíolo en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos.

- Para el escenario 2 (paso 2.1), la medición ya se ha completado; Para el escenario 4 (paso 2.3), continúe con el paso siguiente.

- Mida las variables de los dientes para las hojas preparadas en los escenarios 3 (paso 2.2) y 4 (paso 2.3).

- Mida la hoja en bruto. Con la herramienta de varita, seleccione el interior de la hoja en bruto (es decir, una hoja preparada para las medidas de los dientes que aún tiene sus dientes; Figura 6B). Debe estar delineado en amarillo. Realice mediciones haciendo clic en Analizar > medir o utilizando el acceso directo.

NOTA: Dependiendo de cómo se preparó la hoja, puede ser necesario medir varias secciones disjuntas, sumando sus áreas (por ejemplo, Figura 6B). Alternativamente, puede seleccionar varias secciones a la vez seleccionando una segunda sección con la herramienta de varita mientras mantiene presionada la tecla Mayús . - Registre el área y el perímetro en el área de la hoja sin procesar y el perímetro de la hoja sin procesar en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos.

- Mida la cuchilla interna en bruto. Seleccione el interior de la hoja interna sin tratar (es decir, una hoja preparada para las mediciones de los dientes a la que se le han extraído los dientes; Figura 6B). Debe estar delineado en amarillo. Realice mediciones haciendo clic en Analizar > medir o utilizando el acceso directo.

NOTA: Dependiendo de cómo se preparó la hoja, puede ser necesario medir varias secciones disjuntas, sumando sus áreas (por ejemplo, Figura 6B). Alternativamente, puede seleccionar varias secciones a la vez seleccionando una segunda sección con la herramienta de varita mientras mantiene presionada la tecla Mayús . - Registre el área y el perímetro debajo del área interna de la hoja sin procesar y el perímetro interno de la hoja de cálculo sin procesar en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos.

- Mida la longitud del perímetro de corte. Elimine el umbral para ver la hoja con claridad, haga clic en Restablecer en el cuadro de umbral o haga clic en Editar > Deshacer, este último generalmente también eliminará la conversión de 8 bits en blanco y negro. Seleccione la herramienta de línea segmentada y trace la longitud completa del perímetro de corte en la hoja sin rematar.

- Mida haciendo clic en Analizar > Medir o utilizando el acceso directo. Si hay varias porciones, repita los pasos anteriores para medir la longitud del perímetro de corte de cada porción. Registre la longitud, o la suma de longitudes, en la longitud del perímetro de corte en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos.

NOTA: El perímetro de corte se introduce a través de la preparación de la hoja mediante la eliminación de daños. En la mayoría de los casos, esto es diferente del perímetro medio artificial (Figura 6B). - Cuente los dientes primarios y subsidiarios, si los hay.

NOTA: Consulte la Figura complementaria 2 para obtener consejos sobre cómo distinguir entre dientes primarios y subsidiarios.- Si el umbral aún no se ha eliminado, elimínelo ahora. Para eliminar el umbral, haga clic en Restablecer en el cuadro de umbral o haga clic en Editar > Deshacer, ya que este último también eliminará la conversión de 8 bits en blanco y negro.

- Cuente el número de dientes primarios (consulte la Figura complementaria 2 para obtener consejos sobre cómo distinguir los dientes primarios de los secundarios). Seleccione la herramienta Multipunto. Puede ser necesario hacer clic con el botón derecho del ratón en la herramienta Punto primero, para seleccionar la herramienta Multipunto. Haga clic en cada diente primario para numerarlo.

- Para eliminar un punto seleccionado por error, pulse la tecla Alt (sistema operativo Windows) o Comando/cmd u opción (Mac OS) al mismo tiempo que hace clic en el punto. Registre el número final bajo # de dientes primarios en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos.

- Borre los recuentos y anotaciones de herramientas multipunto haciendo clic en Editar > selección > Seleccionar ninguno o utilice el método abreviado de teclado.

- Cuente el número total de dientes (es decir, todos los dientes primarios y subsidiarios presentes en la hoja). Seleccione la herramienta Multipunto. Puede ser necesario hacer clic con el botón derecho del ratón en la herramienta Punto primero, para seleccionar la herramienta Multipunto. Haga clic en cada diente, incluidos el primario y el subsidiario, para numerarlo.

NOTA: Contar el número total de dientes, en lugar del número de dientes subsidiarios, garantiza que no se cuente dos veces ningún diente. El número total de dientes se resta por el número de dientes primarios para determinar el número de dientes subsidiarios (ver paso 3.11.7.6). - Para eliminar un punto seleccionado por error, pulse la tecla Alt (sistema operativo Windows) o Comando/cmd u opción (Mac OS) al mismo tiempo que hace clic en el punto. Reste el número de dientes primarios del número total de dientes para determinar el número de dientes subsidiarios. Registre esto en # de dientes subsidiarios en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos.

NOTA: Algunos usuarios prefieren hacer recuentos de dientes al preparar imágenes de hojas en lugar de medir.

- Mida la hoja en bruto. Con la herramienta de varita, seleccione el interior de la hoja en bruto (es decir, una hoja preparada para las medidas de los dientes que aún tiene sus dientes; Figura 6B). Debe estar delineado en amarillo. Realice mediciones haciendo clic en Analizar > medir o utilizando el acceso directo.

4. Ejecución de análisis en el software R

NOTA: Los siguientes pasos requieren el paquete R dilp11. La hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos se lee en R y es utilizada por el paquete. Consulte la pestaña Instrucciones adicionales en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos (Archivo complementario 2). El script de R puede acomodar el análisis de varios sitios simultáneamente o de un solo sitio.

- Abra R con su entorno preferido (se recomienda R Studio). Para una introducción a R, véase, por ejemplo, https://cran.r-project.org/doc/manuals/r-release/R-intro.pdf.

- Instale el paquete dilp en la sesión de R. Consulte el siguiente sitio web para obtener más información sobre cómo instalar el paquete y ejecutar sus funciones asociadas: https://cran.r-project.org/package=dilp

- Lea en el archivo .csv que contiene los datos del rasgo de la hoja de la dicotiledónea leñosa fósil (es decir, los datos registrados en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos).

- Ejecute la función dilp() para las reconstrucciones de la temperatura media anual (MAT) y la precipitación media anual (MAP) con error asociado. Los resultados para MAT y MAP se informan a partir de un modelo de regresión lineal múltiple (MLR; es decir, DiLP) y dos modelos de regresión lineal simple (SLR; es decir, análisis de área foliar y márgenes). Ejecute la función lma() para reconstrucciones de masa foliar por área (MA) a nivel de morfotipo y sitio.

- Después de ejecutar dilp(), se recomienda verificar si hay posibles problemas de recopilación de datos y confirmar la calidad de los datos observando los valores atípicos y los objetos de error en los resultados devueltos de dilp( ). Alternativamente, use la función dilp_processing() seguida de dilp_outliers() y dilp_errors(). Resuelva cualquier problema marcado haciendo referencia a la muestra preparada y, potencialmente, volviendo a medirla. Se recomienda editar el archivo de datos original y luego volver a leerlo en R.

- Determine si el sitio fósil se encuentra dentro del espacio multivariado fisionómico de la hoja del conjunto de datos de calibración utilizando la función dilp_cca().

Resultados

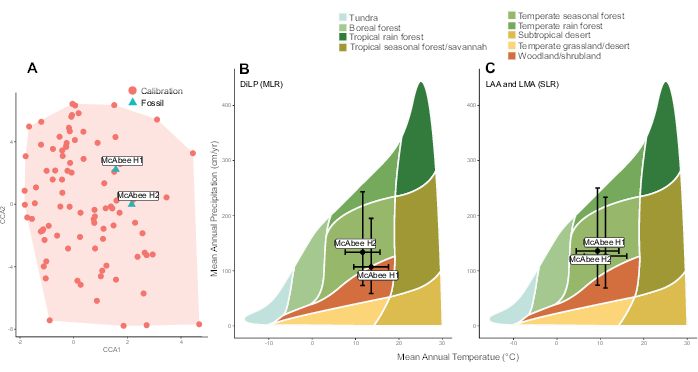

Se utilizó un conjunto de datos previamente publicado de mediciones de fisionomía foliar del yacimiento fósil de McAbee en el centro-sur de la Columbia Británica para proporcionar un ejemplo de resultados representativos utilizando los métodos de reconstrucción de la fisionomía digital de la hoja (DiLP) y de la masa foliar por área (MA) (Lowe et al.38; datos proporcionados en el Archivo Suplementario 2). El sitio ofrece una oportunidad para reconstruir el paleoclima y la paleoecología durante el intervalo más cálido del Cenozoico (el Óptimo Climático del Eoceno Temprano) en un paisaje volcánico y de tierras altas 38,45,46,47. Los ensambles fósiles se muestrearon de dos horizontes separados en una secuencia lacustre, denominados H1 (28 cm de espesor) y H2 (27 cm de espesor), agrupados en un estrecho rango de estratigrafía utilizando una técnica de censo, en la que se recolectaron o contaron todos los especímenes a los que se les podía asignar un morfotipo38,48.

Los datos fisionómicos de la hoja de McAbee pasaron las comprobaciones de errores marcados por dilp_errors(), y siete valores atípicos marcados por dilp_outliers() se verificaron dos veces para garantizar que los valores representaran una variación real en los datos y no un error metodológico. Posteriormente, los datos se ejecutaron a través de la función dilp() para producir paleoclima y la función lma() para reconstrucciones de masa foliar por área.

Las reconstrucciones de MA y los límites inferior y superior de sus intervalos de predicción del 95% se informan en la Tabla 4 tanto a nivel de especie como de sitio, utilizando las ecuaciones presentadas en Royer et al.5 y Butrim et al.10. Los valores reconstruidos están dentro del rango de MA típico de las especies terrestres modernas (30-330 g/m2)49. Usando los umbrales discutidos en Royer et al.5, la mayoría de las especies tienen un MA reconstruido que se alinea con la vida útil de las hojas de <1 año (≤87 g/m2), alrededor de ~1 año (88-128 g/m2), mientras que ninguna es típica de >1 año (≥129 g/m2). Las reconstrucciones del sitio MA la media y la varianza en McAbee reflejan la prevalencia y diversidad de estrategias económicas foliares en un sitio10,50. No hay diferencias prominentes entre la media del sitio y la varianza entre H1 y H2, y por lo tanto, no hay evidencia de que la composición y diversidad de las estrategias económicas foliares variaran entre los dos puntos en el tiempo. Además, las reconstrucciones de la media del sitio realizadas utilizando las ecuaciones de Royer et al.5 y Butrim et al.10 fueron muy similares.

En la Tabla 5 se muestran las reconstrucciones de la temperatura media anual (MAT) y la precipitación media anual (MAP) utilizando las ecuaciones de regresión lineal múltiple (DiLP) y regresión lineal simple (análisis de margen foliar y área foliar) presentadas en Peppe et al.6. Las estimaciones paleoclimáticas se infieren de manera más confiable si la fisionomía foliar de los ensamblajes de hojas fósiles ocurre dentro del espacio fisionómico del conjunto de datos de calibración. Esto se evalúa a través del paso de análisis de correspondencia canónica (CCA) llevado a cabo por la función dilp_cca(). Tanto McAbee H1 como H2 se encuentran dentro del rango de fisionomía foliar observado en el conjunto de datos de calibración (Figura 7A). Si los sitios tenían valores reconstruidos que caían fuera del espacio de calibración, las reconstrucciones paleoclimáticas deben interpretarse con cautela (por ejemplo, a través de la comparación con líneas de evidencia independientes; ver Peppe et al.6 para una discusión más detallada). El MAT y el MAP reconstruidos para H1 y H2 son consistentes con un bioma estacional templado (Figura 7B,C), lo que concuerda bien con líneas de evidencia independientes, incluidas las inferencias basadas en parientes vivos más cercanos de las comunidades fósiles de flores e insectos en McAbee45.

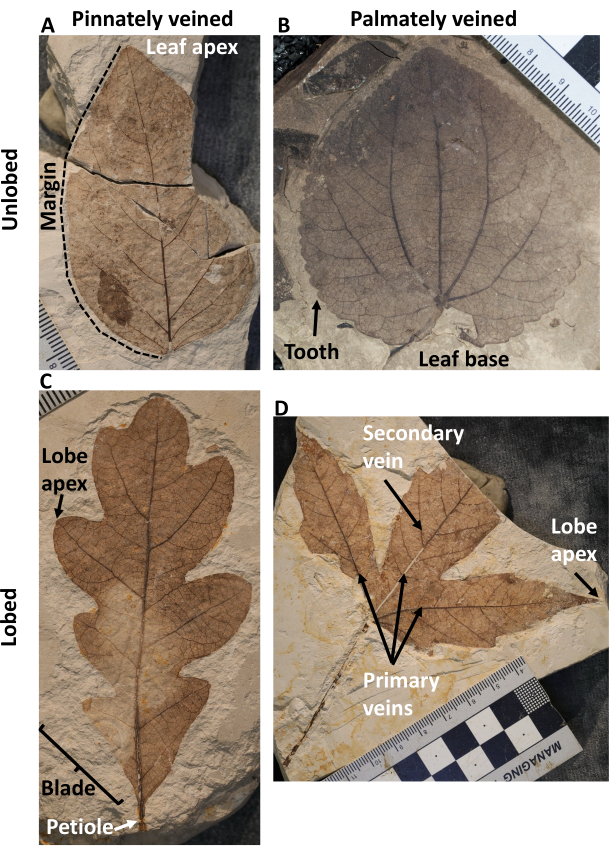

Figura 1: Fisionomía de las hojas y terminología arquitectónica a lo largo de este artículo. (A) Una hoja pinnadamente veteada, sin lóbulos y con márgenes enteros, (B) una hoja palmeadamente venada, sin lóbulos y dentada, (C) una hoja pinnadamente veteada, lobulada y con márgenes enteros, (D) una hoja palmeadamente veteada, lobulada y dentada. Haga clic aquí para ver una versión más grande de esta figura.

Figura 2: Diagrama de flujo del método. Un diagrama de flujo que demuestra cómo las diferentes condiciones de conservación de las hojas y los tipos de hojas determinan qué tipo general de rasgos de las hojas se pueden medir de manera confiable (cuadro amarillo). Esto determina qué escenario de preparación se seguirá en el protocolo y en qué columnas se ingresarán los datos en la hoja de cálculo de entrada de datos (viñetas). Haga clic aquí para ver una versión más grande de esta figura.

Figura 3: Diferentes escenarios de preparación. Diferentes escenarios de preparación que muestran ejemplos de imágenes completadas y preparadas digitalmente listas para la fase de medición. (A) Escenario 1, hoja entera con márgenes cuya área, o la mitad del área, no se puede reconstruir, (B) Escenario 5, hoja dentada cuya área, o la mitad del área, no se puede reconstruir y no tiene ≥2 dientes consecutivos y/o el ≥25% de la hoja preservada, (C) Escenario 2, hoja entera con márgenes cuya área, o la mitad del área, se conserva o puede reconstruirse, (D) Escenario 3, una hoja dentada cuya área, o la mitad del área, no se puede reconstruir pero tiene ≥2 dientes consecutivos y se conserva el ≥25% de la hoja, (E) Escenario 4, una hoja dentada cuya área, o la mitad del área, se conserva o se puede reconstruir. Haga clic aquí para ver una versión más grande de esta figura.

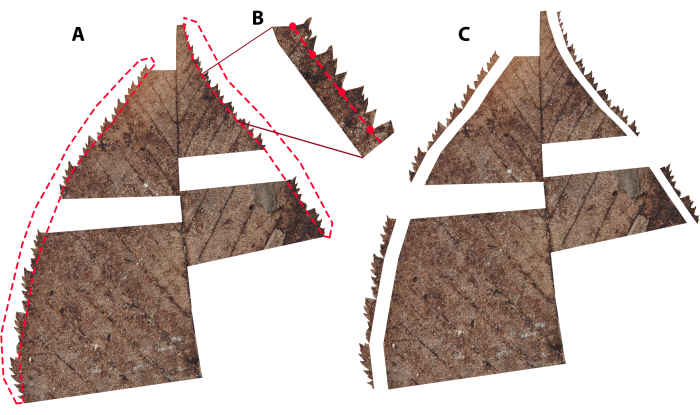

Figura 4: Ilustración de la eliminación de daños. Ilustra cómo cortar el margen dañado y el área de la hoja adyacente a ese margen dañado. Las líneas rojas discontinuas muestran cómo se realizan las selecciones con la herramienta Lazo. Tenga en cuenta que los límites del daño se iniciaron intencionalmente en los senos paranasales de los dientes primarios (consulte la Figura complementaria 2 para obtener ayuda para diferenciar los dientes primarios de los auxiliares). (A) Una hoja con nervaduras pinnadas donde la selección se extiende hasta la mitad de la nervadura. (B) Una hoja palmeada con nervaduras donde la selección se extiende hasta la vena primaria más cercana. Haga clic aquí para ver una versión más grande de esta figura.

Figura 5: Ilustrando un ejemplo de cómo cortar dientes. (A) Las líneas rojas discontinuas demuestran cómo se realizan las selecciones con la herramienta Lazo. Tenga en cuenta que en este caso, los dientes son compuestos, por lo que las selecciones se realizaron solo entre los senos primarios (consulte la Figura complementaria 2 para obtener ayuda para diferenciar los dientes primarios de los auxiliares), (B) una perspectiva ampliada de cómo se realizó la selección de los dientes, con puntos rojos que representan dónde se hizo clic con el mouse durante la selección, (C) la copia de la hoja cuando se extraen los dientes. Haga clic aquí para ver una versión más grande de esta figura.

Figura 6: Ilustración del escenario de preparación 4. Ilustración de las decisiones de preparación y los pasos de medición para una hoja de ejemplo preparada en el escenario 4. (A) Un escenario de preparación en el que se decidió que una media hoja proporcionaba las mediciones más confiables de la forma y el área de la hoja, y se incluyeron márgenes conservados en ambas mitades mediales para las mediciones de los dientes. (B) Un ejemplo que demuestre qué variables se miden en varios componentes de la hoja preparada. El texto en negrita resalta las mediciones necesarias para los análisis de DiLP y MA , mientras que el texto sin negrita (perímetro de la hoja, Feret mínimo y perímetro medio artificial) resalta las mediciones que no son necesarias pero útiles para caracterizaciones fisionómicas adicionales (p. ej., factor de forma y compacidad; Tabla 1). Haga clic aquí para ver una versión más grande de esta figura.

Figura 7: Resultados representativos. Resultados de dos horizontes fósiles (H1 y H2) muestreados en los lechos fósiles McAbee del Eoceno temprano de Lowe et al.38. (A) Análisis de correspondencias canónicas que muestra la representación de la fisionomía foliar multivariante en el conjunto de datos de calibración. Los datos de calibración son de Peppe et al.6. La fisonomía foliar de los dos horizontes de McAbee se superpone y se produce dentro del espacio de calibración. (B y C) Estimaciones de temperatura y precipitación, y su incertidumbre asociada (errores estándar de los modelos), utilizando las ecuaciones presentadas en Peppe et al.6 de los dos horizontes de McAbee superpuestos en un diagrama del bioma de Whittaker. (B) Estimaciones reconstruidas utilizando los modelos de regresión lineal múltiple (MLR) de Digital Leaf Physiognomy (DiLP), (C) Estimaciones reconstruidas utilizando las ecuaciones de regresión lineal simple (SLR) de análisis de área foliar (LAA) y análisis de margen foliar (LMA) de los dos horizontes de McAbee superpuestos en un diagrama de Whittaker Biome. Haga clic aquí para ver una versión más grande de esta figura.

Tabla 1: Variables fisionómicas de la hoja. Variables que se miden y/o calculan y aplican en modelos predictivos que utilizan este protocolo para reconstruir la masa seca foliar por área (MA), la temperatura media anual (MAT) y la precipitación media anual (MAP). El MAT y el MAP se reconstruyen con las ecuaciones presentadas en Peppe et al.6 utilizando un enfoque multivariado para la Fisionomía Digital de la Hoja (DiLP) y enfoques univariados para el análisis del margen foliar (LMA) y el análisis del área foliar (LAA). Las variables enumeradas como Otras no se utilizan en los análisis MA, DiLP, LMA y LAA, pero aún así se miden y calculan utilizando este protocolo porque son fáciles de implementar y proporcionan caracterizaciones útiles de la fisionomía de las hojas. Haga clic aquí para descargar esta tabla.

Tabla 2: Consideraciones y explicaciones adicionales para los pasos de preparación. Haga clic aquí para descargar esta tabla.

Tabla 3: Consideraciones y explicaciones adicionales para los pasos de medición. Haga clic aquí para descargar esta tabla.

Tabla 4: Reconstrucciones de la masa seca foliar por área (MA) y los límites superior e inferior asociados de los intervalos de predicción del 95% para los lechos fósiles de McAbee de Lowe et al.38. Las reconstrucciones se realizan para la media del morfotipo5, la media del sitio 5,10 y la varianza del sitio10. Haga clic aquí para descargar esta tabla.

Tabla 5: Reconstrucciones de la templada media anual (MAT) y la precipitación media anual (MAP) para el Horizonte 1 (H1) y 2 (H2) en los lechos fósiles de McAbee del Eoceno temprano utilizando las regresiones lineales múltiples (MLR) de la fisionomía digital de la hoja (DiLP) y las regresiones lineales simples (SLR) del análisis del margen foliar (LMA) y el análisis del área foliar (LAA) presentadas en Peppe et al.6. Haga clic aquí para descargar esta tabla.

Figura suplementaria 1: Hoja de Quercus rubra del bosque de Harvard que ilustra la regla del lóbulo frente al diente. Los segmentos de línea p y d se definen en el texto. Barras de escala = 1 cm. Haga clic aquí para descargar este archivo.

Figura complementaria 2: Hoja de Betula lutea del bosque de Harvard que ilustra las reglas para diferenciar los dientes subsidiarios de los dientes primarios. El segmento foliar aislado se ha magnificado 2 veces. La línea azul conecta los senos paranasales con el mayor grado de incisión (es decir, senos paranasales primarios), y los dientes asociados con estos senos paranasales se consideran primarios (flechas azules). Los puntos rojos marcan dientes que se pueden diferenciar como subsidiarios porque sus senos apicales están incisos en menor grado. Los dientes marcados por las flechas rojas tienen un grado similar de incisión en comparación con los dientes primarios, pero pueden identificarse como subsidiarios por una vena principal relativamente más delgada en comparación con los dientes primarios. Barras de escala = 1 cm. Haga clic aquí para descargar este archivo.

Figura complementaria 3: Ilustración de la selección de dientes, la regla del lóbulo pinnado y la regla de prioridad del lóbulo. (A) Selección de dientes para una hoja de Hamamelis virginiana de la Reserva de Huyck. Las áreas oscurecidas corresponden al tejido foliar que se incluye en la selección total de dientes porque los dientes subsidiarios se diferencian de los dientes primarios. (B) La hoja de Quercus alba de IES ilustra la regla de prioridad de lóbulos. Las áreas oscurecidas se miden como lóbulos y las no oscurecidas se miden como dientes, pero todas las proyecciones se consideran lóbulos a través de la regla de prioridad de lóbulos. Barras de escala = 1 cm. Haga clic aquí para descargar este archivo.

Figura suplementaria 4: Hoja de Acer saccharum del Bosque Nacional Allegheny que ilustra las reglas de extensión y diente solitario. Las líneas discontinuas representan selecciones de dientes. La línea continua representa el eje de simetría del diente asociado. El área negra es un peso que se utiliza para aplanar las hojas para la fotografía. Barras de escala = 1 cm. Haga clic aquí para descargar este archivo.

Figura complementaria 5: Ilustrando la forma ideal de cortar un pecíolo que se coloca encima de una base cordiforme. Haga clic aquí para descargar este archivo.

Fichero complementario 1: Plantilla de entrada de datos para todas las variables de fisionomía digital de hojas medidas. Este archivo no debe modificarse, ya que se utilizará como archivo de entrada para el paquete de R. Haga clic aquí para descargar este archivo.

Archivo suplementario 2: Ejemplo de datos de lechos fósiles de McAbee de Lowe et al.38. Estos datos se utilizaron para generar la Figura 7 y para la discusión de resultados representativos. Haga clic aquí para descargar este archivo.

Legajo complementario 3: Documento de normas para la fisionomía digital de hojas fósiles. Haga clic aquí para descargar este archivo.

Discusión

Este artículo presenta cómo los rasgos continuos de la fisionomía de las hojas pueden medirse en hojas fósiles de angiospermas dicotiledóneas leñosas y posteriormente aplicarse a proxies desarrollados a partir de datos de calibración modernos para reconstruir el paleoclima y la paleoecología. Esto requiere que se tenga cuidado de alinear los pasos metodológicos con los representados en los conjuntos de datos de calibración proxy 5,6,10. Esta consideración comienza antes de la aplicación de este protocolo durante la recolección de hojas fósiles, particularmente con respecto al tamaño de la muestra. Se recomienda agrupar los ensamblajes de hojas fósiles en un rango de estratigrafía lo más estrecho posible para obtener un número adecuado de especímenes y morfotipos medibles para minimizar el promedio de tiempo. También se recomienda limitar la reconstrucción paleoclimática a sitios con al menos 350 especímenes identificables y al menos 15-20 morfotipos de angiospermas dicotiledóneas leñosas 19,51,52. Además, al elegir las hojas para los análisis, se recomienda medir el mayor número posible de hojas por morfotipo y, como mínimo, elegir especímenes que representen la variabilidad de la fisionomía de las hojas dentro de un morfotipo.

Se debe tener más cuidado al implementar las secciones de preparación y medición para mantener la coherencia con el conjunto de datos de calibración. Los pasos llevados a cabo durante las etapas de preparación tienen el mayor potencial de subjetividad y resultados variados entre los usuarios. Sin embargo, si se sigue deliberadamente el protocolo y se hace referencia a menudo a las tablas de consideraciones adicionales (Tabla 2, Tabla 3) y al documento de reglas (Archivo Suplementario 3), este método da como resultado mediciones objetivas y reproducibles de la fisionomía de las hojas. Para los usuarios nuevos en el método, se sugiere confirmar que las hojas se han preparado correctamente con alguien que tenga más experiencia. Se debe tener especial cuidado al medir el ancho del pecíolo para las reconstrucciones MA . Debido a que estos valores son cuadrados, la inexactitud en las mediciones se volverá exagerada. La conservación incompleta y los daños pueden alterar las dimensiones del pecíolo y deben evitarse cuidadosamente.

Hay algunas limitaciones de estos métodos que vale la pena señalar. Lo más importante es que las reconstrucciones indirectas incluidas en el paquete dilp R son solo para angiospermas dicotiledóneas leñosas y, por lo tanto, pueden excluir otros grupos de plantas que fueron componentes prominentes de comunidades antiguas. Sin embargo, se han publicado proxies adicionales basados en pecíolos foliares para MA a nivel de especie para gimnospermas pecioladas y de hoja ancha 5,8, angiospermas herbáceas8 y helechos9, que un usuario podría incorporar por separado si lo desea. La exclusión de grupos de plantas prominentes en comunidades más allá de las angiospermas dicotiledóneas leñosas es probablemente el mayor impacto para las reconstrucciones de la media y la varianza de MA a nivel de sitio, ya que proporcionarán una perspectiva incompleta de las estrategias económicas dentro de toda la comunidad. La historia filogenética influye en la aparición de los dientes de las hojas23, introduciendo el potencial de que el análisis de comunidades fósiles con una composición taxonómica novedosa puede impartir incertidumbre en las estimaciones resultantes, aunque la realización de esta influencia potencial aún no ha sido probada y demostrada.

Las hojas fósiles también necesitan ser preservadas adecuadamente para incorporar mediciones cuantitativas de la fisionomía de las hojas más allá del estado de margen. En el caso de DiLP, esto es especialmente cierto en el caso de las hojas con márgenes completos, ya que sólo pueden aportar información más allá del estado de margen si la hoja entera, o la mitad de la hoja, se conserva o se puede reconstruir. Del mismo modo, las hojas solo pueden incorporarse a las reconstrucciones MA si (1) se conserva tanto su pecíolo en su inserción en la lámina de la hoja o, en casos específicos, si se conserva la base de la hoja como la porción más basal de la vena media (véase la nota en el paso 3.6), y (2) si se puede estimar el tamaño de la hoja, ya sea a través de la medición de hojas enteras o la reconstrucción de medias hojas. Esto significa que algunos morfotipos pueden excluirse por completo de los análisis MA nivel de sitio. Por último, el tiempo es una limitación con este protocolo, ya que las alternativas univariadas para las reconstrucciones paleoclimáticas tardan comparativamente menos tiempo en producirse.

A pesar de estas limitaciones, el uso de los métodos de reconstrucción DiLP y MA todavía tiene varias ventajas sobre otros métodos. Las reconstrucciones de MA son una de las únicas formas de reconstruir las estrategias económicas de las hojas en el registro fósil, y el uso de mediciones bidimensionales del ancho del pecíolo y el área de las hojas permite que las reconstrucciones se realicen utilizando fósiles de hojas comunes de impresión/compresión. Para DiLP, la incorporación de múltiples mediciones continuas que están funcionalmente vinculadas con el clima mejora la reproducibilidad de las mediciones y la precisión de las reconstrucciones climáticas resultantes 6,13. Este protocolo está diseñado para adaptarse a la naturaleza incompleta del registro fósil al permitir que las mediciones de la dentadura de las hojas se realicen utilizando fragmentos de hojas. Aunque las mediciones continuas del área foliar proporcionan más información sobre el tamaño de la hoja, las estimaciones de DiLP MAP pueden complementarse con aquellas que utilizan clases de tamaño de hoja en un esfuerzo por aumentar el tamaño de la muestra16,53 o mediante la incorporación de estimaciones de escala de venas del área foliar 42,54,55. Al igual que con la mayoría de los métodos involucrados, la eficiencia del tiempo de este protocolo mejorará a medida que el usuario adquiera más experiencia y confianza, particularmente en los pasos de preparación. El hecho de que las mediciones de DiLP a nivel de sitio se hayan realizado siguiendo este protocolo para >150 ensamblajes modernos 6,10,56 y al menos 22 fósiles hasta la fecha atestigua su factibilidad 6,38,39,40,41,42. Por último, las mediciones exhaustivas de la fisionomía de las hojas tienen aplicaciones más allá de las discutidas aquí y pueden ser útiles para describir otros aspectos de la ecología, la fisiología, la evolución y el desarrollo de las plantas, con aplicación tanto en los estudios modernos56 como en los paleo40.

En resumen, la implementación de los métodos detallados en este artículo permite al usuario reconstruir el paleoclima y la paleoecología utilizando métodos robustos y reproducibles. Estos métodos brindan una oportunidad importante para mostrar ejemplos pasados de respuestas climáticas y de los ecosistemas a las perturbaciones ambientales y para proporcionar más información sobre las complejas interacciones de los sistemas naturales de la Tierra.

Divulgaciones

Ninguno.

Agradecimientos

AJL agradece al Equipo Hoja de pregrado 2020-2022 de la Universidad de Washington por la motivación y las sugerencias para hacer materiales de capacitación efectivos para DiLP. AGF, AB, DJP y DLR agradecen a los muchos estudiantes de pregrado de la Universidad Wesleyan y la Universidad de Baylor que midieron hojas modernas y fósiles y cuyo aporte fue invaluable para modificar y actualizar este protocolo. Los autores agradecen al Grupo de Trabajo de Rasgos Cuantitativos de PBot y al equipo del PBOT por alentar el trabajo para formalizar este protocolo para hacerlo más accesible a comunidades más amplias. Este trabajo fue apoyado por la Fundación Nacional de Ciencias (subvención EAR-0742363 para DLR, subvención EAR-132552 para DJP) y la Universidad de Baylor (Programa de Desarrollo de Jóvenes Investigadores para DJP). Agradecemos a dos revisores anónimos y al editor de la revisión por sus comentarios que ayudaron a mejorar la claridad y la exhaustividad de este protocolo.

Materiales

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Copy stand or tripod | For fossil photography | ||

| Digital camera | For fossil photography, high resolution camera preferred | ||

| Image editing software | For digital preperation. Examples include Adobe Photoshop and GIMP, the latter of which is free (https://www.gimp.org/) | ||

| ImageJ software | IJ1.46pr | For making digital measurments, free software (https://imagej.net/ij/index.html) | |

| Microsoft Excel | Microsoft | Or similar software for data entry | |

| R software | The R foundation | For running provided R script (https://www.r-project.org/). R studio offers a user friendly R enviornment (https://posit.co/download/rstudio-desktop/). Both are free. | |

| dilp R Package | Can be installed following instructions here: https://github.com/mjbutrim/dilp |

Referencias

- Gates, D. M. Transpiration and leaf temperature. Ann Rev Plant Physiol. 19 (1), 211-238 (1968).

- Givnish, T. On the adaptive significance of leaf form. Topics Plant Pop Biol. , 375-407 (1979).

- Niklas, K. J. . Plant biomechanics: an engineering approach to plant form and function. , (1992).

- Niklas, K. J. . Plant Allometry: The Scaling of Form and Process. , (1994).

- Royer, D. L., et al. Fossil leaf economics quantified: Calibration, Eocene case study, and implications. Paleobiology. 33 (4), 574-589 (2007).

- Peppe, D. J., et al. Sensitivity of leaf size and shape to climate: global patterns and paleoclimatic applications. New Phytol. 190 (3), 724-739 (2011).

- Wright, I. J., et al. The worldwide leaf economics spectrum. Nature. 428 (6985), 821-827 (2004).

- Royer, D. L., Miller, I. M., Peppe, D. J., Hickey, L. J. Leaf economic traits from fossils support a weedy habit for early angiosperms. Am J Botany. 97 (3), 438-445 (2010).

- Peppe, D. J., et al. Biomechanical and leaf-climate relationships: a comparison of ferns and seed plants. Am J Botany. 101 (2), 338-347 (2014).

- . dilp: Reconstruct paleoclimate and paleoecology with leaf physiognomy. R package version 1.1.0 Available from: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/dilp/index.html (2024)

- Bailey, I. W., Sinnott, E. W. A botanical index of Cretaceous and Tertiary climates. Science. 41 (1066), 831-834 (1915).

- Bailey, I. W., Sinnott, E. W. The climatic distribution of certain types of angiosperm leaves. Am J Botany. 3 (1), 24-39 (1916).

- Peppe, D. J., Baumgartner, A., Flynn, A. G., Blonder, B. Reconstructing paleoclimate and paleoecology using fossil leaves. Meth Paleoecol: Reconstructing Cenozoic Terre Environ Ecol Comm. , 289-317 (2018).

- Wolfe, J. A. . Temperature parameters of humid to mesic forests of eastern Asia and relation to forests of other regions of the Northern Hemisphere and Australasia. , (1979).

- Wilf, P. When are leaves good thermometers? A new case for Leaf Margin Analysis. Paleobiology. 23 (3), 373-390 (1997).

- Wilf, P., Wing, S. L., Greenwood, D. R., Greenwood, C. L. Using fossil leaves as paleoprecipitation indicators: An Eocene example. Geology. 26 (3), 203-206 (1998).

- Miller, I. M., Brandon, M. T., Hickey, L. J. Using leaf margin analysis to estimate the mid-Cretaceous (Albian) paleolatitude of the Baja BC block. Earth Planetary Sci Lett. 245 (1), 95-114 (2006).

- Wing, S. L., Greenwood, D. R. Fossils and fossil climate: The case for equable continental interiors in the Eocene. Philosophical Transact: Biol Sci. 341 (1297), 243-252 (1993).

- Wolfe, J. A. A method of obtaining climatic parameters from leaf assemblages. U S Geol Sur. (2040), 1-71 (1993).

- Huff, P. M., Wilf, P., Azumah, E. J. Digital future for paleoclimate estimation from fossil leaves? Preliminary results. Palaios. 18 (3), 266-274 (2003).

- Spicer, R. A. Recent and future developments of CLAMP: Building on the legacy of Jack A. Wolfe. Adv Angiosperm Paleobotany Paleoclimatic Reconstruct. 258, 109-118 (2007).

- Yang, J., Spicer, R. A., Spicer, T. E. V., Li, C. S. CLAMP Online': a new web-based palaeoclimate tool and its application to the terrestrial Paleogene and Neogene of North America. Palaeobiodivers Palaeoenviron. 91 (3), 163-183 (2011).

- Little, S. A., Kembel, S. W., Wilf, P. Paleotemperature proxies from leaf fossils reinterpreted in light of evolutionary history. PLoS One. 5 (12), e15161 (2010).

- Webb, L. J. A physiognomic classification of Australian rain forests. J Ecol. 47 (3), 551-570 (1959).

- Schmerler, S. B., et al. Evolution of leaf form correlates with tropical-temperate transitions in Viburnum (Adoxaceae). Proc Royal Soci B: Biol Sci. 279 (1744), 3905-3913 (2012).

- Nicotra, A. B., et al. The evolution and functional significance of leaf shape in the angiosperms. Funct Plant Biol. 38 (7), 535-552 (2011).

- Leigh, A., Sevanto, S., Close, J. D., Nicotra, A. B. The influence of leaf size and shape on leaf thermal dynamics: does theory hold up under natural conditions. Plant Cell Environ. 40 (2), 237-248 (2017).

- Wright, I. J., et al. Global climatic drivers of leaf size. Science. 357 (6354), 917-921 (2017).

- Givnish, T. J. Leaf and canopy adaptations in tropical forests. Physiol Ecol Plants Wet Tropics. 12, 51-84 (1984).

- Feild, T. S., Sage, T. L., Czerniak, C., Iles, W. J. Hydathodal leaf teeth of Chloranthus japonicus (Chloranthaceae) prevent guttation-induced flooding of the mesophyll. Plant, Cell Environ. 28 (9), 1179-1190 (2005).

- Royer, D. L., Wilf, P. Why do toothed leaves correlate with cold climates? Gas exchange at leaf margins provides new insights into a classic paleotemperature proxy. Int J Plant Sci. 167 (1), 11-18 (2006).

- Edwards, E. J., Spriggs, E. L., Chatelet, D. S., Donoghue, M. J. Unpacking a century-old mystery: Winter buds and the latitudinal gradient in leaf form. Botanical Soc Am. 103 (6), 975-978 (2016).

- Givnish, T. J., Kriebel, R. Causes of ecological gradients in leaf margin entirety: Evaluating the roles of biomechanics, hydraulics, vein geometry, and bud packing. Am J Botany. 104 (3), 354-366 (2017).

- Royer, D. L., Wilf, P., Janesko, D. A., Kowalski, E. A., Dilcher, D. L. Correlations of climate and plant ecology to leaf size and shape: potential proxies for the fossil record. Am J Botany. 92 (7), 1141-1151 (2005).

- Green, W. A. Loosening the CLAMP: an exploratory graphical approach to the climate leaf analysis multivariate program. Palaeontol Electro. 9 (2), 19 (2006).

- Peppe, D. J., Royer, D. L., Wilf, P., Kowalski, E. A. Quantification of large uncertainties in fossil leaf paleoaltimetry. Tectonics. 29 (3), 002549 (2010).

- Royer, D. L., Meyerson, L. A., Robertson, K. M., Adams, J. M. Phenotypic plasticity of leaf shape along a temperature gradient in Acer rubrum. PLoS One. 4 (10), e7653 (2009).

- Lowe, A. J., et al. Plant community ecology and climate on an upland volcanic landscape during the early Eocene climatic optimum: McAbee fossil beds, British Columbia, Canada. Palaeogeograp, Palaeoclimatol, Palaeoecol. 511, 433-448 (2018).

- Flynn, A. G., Peppe, D. J. Early Paleocene tropical forest from the Ojo Alamo Sandstone, San Juan Basin, New Mexico, USA. Paleobiology. 45 (4), 612-635 (2019).

- Allen, S. E., Lowe, A. J., Peppe, D. J., Meyer, H. W. Paleoclimate and paleoecology of the latest Eocene Florissant flora of central Colorado, U.S.A. Palaeogeograp, Palaeoclimatol, Palaeoecol. 551, 109678 (2020).

- Baumgartner, A., Peppe, D. J. Paleoenvironmental changes in the Hiwegi Formation (lower Miocene) of Rusinga Island, Lake Victoria, Kenya. Palaeogeograp, Palaeoclimatol, Palaeoecol. 574, 110458 (2021).

- Wagner, J. D., Peppe, D. J., O'keefe, J. M., Denison, C. N. Plant community change across the Paleocene-Eocene boundary in the Gulf coastal plain, Central Texas. Palaios. 38 (10), 436-451 (2023).

- Ellis, B., et al. . Manual of leaf architecture. , (2009).

- Schneider, C. A., Rasband, W. S., Eliceiri, K. W. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Meth. 9, 671-675 (2012).

- Greenwood, D. R., Pigg, K. B., Basinger, J. F., DeVore, M. L. A review of paleobotanical studies of the Early Eocene Okanagan (Okanogan) Highlands floras of British Columbia, Canada, and Washington, USA. Canadian J Earth Sci. 53 (6), 548-564 (2016).

- Lowe, A. J., West, C. K., Greenwood, D. R. Volcaniclastic lithostratigraphy and paleoenvironment of the lower Eocene McAbee fossil beds, Kamloops Group, British Columbia, Canada. Canadian J Earth Sci. 55 (8), 923-934 (2018).

- Lowe, A. J., et al. Dynamics of deposition and fossil preservation at the early Eocene Okanagan Highlands of British Columbia, Canada: insights from organic geochemistry. Palaios. 37 (5), 185-200 (2022).

- Gushulak, C. A. C., West, C. K., Greenwood, D. R. Paleoclimate and precipitation seasonality of the Early Eocene McAbee megaflora, Kamloops Group, British Columbia. Canadian J Earth Sci. 53 (6), 591-604 (2016).