JoVE 비디오를 활용하시려면 도서관을 통한 기관 구독이 필요합니다. 전체 비디오를 보시려면 로그인하거나 무료 트라이얼을 시작하세요.

Method Article

생체 재료에 대한 세포 독성 및 세포 반응에 접근

* 이 저자들은 동등하게 기여했습니다

요약

이 방법론은 유세포 분석, RT-PCR, 면역세포화학, 기타 세포 및 분자 생물학 기술을 포함한 생존력 분석 및 표현형 분석을 사용하여 가용성 추출물의 제조를 통해 생체 재료 세포 독성을 평가하는 것을 목표로 합니다.

초록

생체 재료는 인체 조직과 직간접적으로 접촉하므로 세포 독성을 평가하는 것이 중요합니다. 이 평가는 여러 가지 방법으로 수행 할 수 있지만 사용 된 접근법간에 높은 불일치가 존재하여 재현성과 얻은 결과 간의 비교가 손상됩니다. 본 논문에서는 치과용 생체재료에 사용하는 수용성 추출물을 이용하여 생체재료 세포독성을 평가하는 프로토콜을 제안한다. 추출물 준비는 펠렛 생산에서 배양 배지에서의 추출에 이르기까지 자세히 설명되어 있습니다. 생체 재료 세포 독성 평가는 MTT 분석을 사용한 대사 활성, Sulphorhodamine B(SBR) 분석을 사용한 세포 생존율, 유세포 분석에 의한 세포 사멸 프로파일, May-Grünwald Giemsa를 사용한 세포 형태를 기반으로 합니다. 세포독성 평가에 추가하여, 세포 기능을 평가하기 위한 프로토콜은 면역세포화학 및 PCR에 의해 평가된 특정 마커의 발현을 기반으로 설명된다. 이 프로토콜은 추출물 방법론을 사용하여 재현 가능하고 강력한 방식으로 생체 재료 세포 독성 및 세포 효과 평가를 위한 포괄적인 가이드를 제공합니다.

서문

생체적합성은 조직을 통합하고 국소 및 전신 손상이 없는 유리한 치료 반응을 유도하는 물질의 능력으로 정의할 수 있다 1,2,3. 생체 적합성 평가는 의료용 재료의 개발에 매우 중요합니다. 따라서 이 프로토콜은 새로운 생체 재료 개발을 목표로 하거나 기존 생체 재료에 대한 새로운 응용 프로그램을 연구하는 모든 연구자에게 체계적이고 포괄적인 접근 방식을 제공합니다.

시험관 내 세포 독성 시험은 일차 세포 배양 또는 세포주를 사용하여 생체 적합성 평가의 첫 번째 단계로 널리 사용됩니다. 결과는 잠재적인 임상 적용의 첫 번째 지표를 구성합니다. 이 테스트는 생체 재료 개발에 필수적일 뿐만 아니라 EUA 및 EU 규제 기관(FDA 및 CE 인증)4,5,6,7,8의 시장 도입에 대한 현재 규정을 준수해야 합니다. 또한, 생물의학 연구의 표준화된 시험은 유사한 생체 재료 또는 장치에 대한 다양한 연구 결과의 재현성 및 비교 측면에서 상당한 이점을 제공한다9.

ISO(International Organization for Standardization) 지침은 정확하고 재현 가능한 방식으로 재료를 테스트하기 위해 여러 독립적인 상업, 규제 및 학술 실험실에서 널리 사용됩니다. ISO 10993-5는 시험관 내 세포 독성 평가를 의미하며 ISO 10993-12는 샘플링 제제10,11에 보고합니다. 생체 재료 테스트를 위해 재료 유형, 접촉 조직 및 치료 목표에 따라 선택되는 세 가지 범주가 제공됩니다 : 추출물, 직접 접촉 및 간접 접촉 8,11,12,13. 추출물은 세포 배양 배지를 생체 재료로 풍부하게 하여 얻는다. 직접 접촉 시험을 위해, 생체 재료를 세포 배양물 상에 직접 위치시키고, 간접 접촉에서, 세포와의 인큐베이션은 아가로스 겔(11)과 같은 장벽에 의해 분리되어 수행된다. 적절한 통제가 필수적이며 최소 3 개의 독립적 인 실험이 수행되어야합니다 5,8,10,11,14.

세포 독성 가능성을 결정하기 위해 임상 조건을 시뮬레이션하거나 과장하는 것이 중요합니다. 추출물 테스트의 경우 재료의 표면적; 중간 볼륨; 배지 및 물질 pH; 물질 용해도, 삼투압 및 확산 비율; 교반, 온도 및 시간과 같은 추출 조건은 배지 농축제에 영향을 미칩니다5.

이 방법론은 고체 및 액체의 여러 제약 제형의 세포 독성에 대한 정량적 및 정성적 평가를 허용합니다. 중성 적색 흡수 시험, 집락 형성 시험, MTT 검정 및 XTT 검정 5,10,14와 같은 여러 검정을 수행할 수 있습니다.

발표된 대부분의 세포독성 평가 연구는 제한된 정보를 제공하는 MTT 및 XTT와 같은 더 간단한 분석을 사용합니다. 생체적합성 평가는 세포독성의 평가뿐만 아니라 주어진 시험 물질2의 생체활성의 평가를 포함해야 한다. 정당화되고 문서화된 경우 추가 평가 기준을 사용해야 합니다. 따라서 이 프로토콜은 생체 재료 세포 독성 평가를 위한 일련의 방법을 자세히 설명하는 포괄적인 가이드를 제공하는 것을 목표로 합니다. 게다가, 다양한 세포 과정, 즉 세포 사멸의 유형, 세포 형태, 특정 단백질 합성에서의 세포 기능 및 특정 조직 생산에 대한 평가가 설명됩니다.

프로토콜

1. 펠렛 준비

- PVC 플레이트에 알려진 치수의 원형 구멍을 수행하여 폴리염화비닐(PVC) 몰드를 준비합니다.

알림: PVC 몰딩은 다양한 크기로 만들 수 있습니다. 공식 A= h(2πr)+2πr2 (r: 원통의 반지름, h: 원통의 높이)를 사용하여 PVC 몰드의 접촉면을 계산합니다. - 제조업체의 지침에 따라 테스트 할 생체 재료를 준비하십시오.

참고: 페이스트/페이스트 제형 바이오 재료의 준비를 위해 적절한 양의 베이스 페이스트와 촉매를 혼합 주걱으로 수동으로 혼합합니다. 액체 및 분말 제형을 기반으로 하는 다른 재료의 경우 제조업체의 지침에 따라 또는 적절한 새 재료에 따라 수동 스패테이션 또는 진동과 기계적 혼합을 수행해야 합니다. 액체 재료의 경우 이 단계가 필요하지 않습니다. 2단계에서 프로토콜을 시작합니다. - 주걱으로 생체 재료를 금형에 놓고 적절한 시간 동안 고정시킵니다.

알림: 생체 재료의 경화 시간 및 경화 조건은 제조업체의 지침을 따르거나 새로운 재료에 적합해야 합니다. - 설정 후, PVC 몰드에서 생체 재료의 펠릿을 제거하고 용기에 넣습니다(6웰 플레이트 또는 페트리 접시 사용 가능).

- 펠릿을 자외선 (UV) 램프 아래에 두어 각 면에 대해 20분 동안 소독합니다.

2. 생체 재료의 추출물 얻기

알림: 모든 절차는 엄격한 멸균 조건에서 수행해야 합니다.

- 1.1에 설명된 공식에 따라 펠릿 표면적을 계산하여 필요한 펠릿 수를 결정합니다.

참고: 기준 값으로, 250 mm2/mL11,15의 접촉 표면적은 배지 mL당 9개의 펠릿(r 3 mm x h 1.5 mm)을 추가하여 달성됩니다. - 가용성 추출물(생체 재료가 풍부한 추출물)을 준비합니다.

- 펠릿을 50mL 튜브에 넣고 해당 세포 배양 배지를 추가합니다. 튜브를 37°의 인큐베이터에 24시간 동안 일정한 회전으로 놓습니다.

참고: 세포 배양에 적합한 세포 배양 배지를 사용하십시오. - 24 시간 후 인큐베이터에서 튜브를 꺼냅니다. 이 시점에서, 추출물은 1/1 또는 100%의 농도에 상응한다.

- 동일한 부피의 컨디셔닝 배지를 세포 배양 배지에 순차적으로 첨가하여 추출물을 희석합니다.

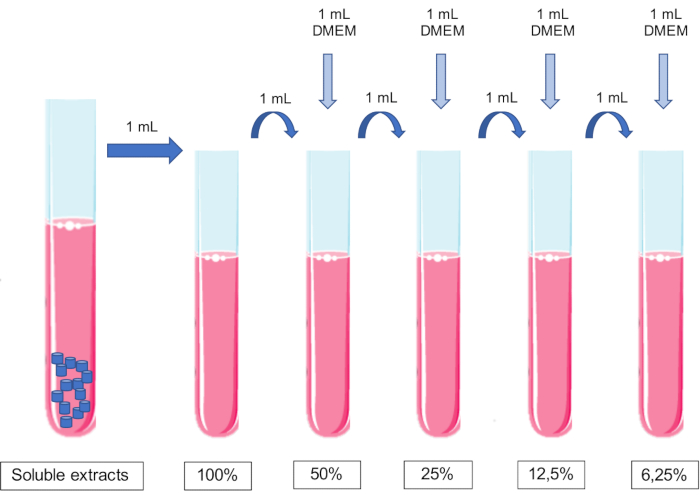

알림: 매체에 pH를 조정해서는 안 됩니다.- 100% 추출물 1mL에 배양액 1mL를 가하여 50% 추출물을 얻었다. 50% 추출물 1mL에 배양액 1mL를 추가하여 25% 추출물을 얻는 식입니다(그림 1).

참고: 각 화합물과 관련된 농도를 사용하십시오.

- 100% 추출물 1mL에 배양액 1mL를 가하여 50% 추출물을 얻었다. 50% 추출물 1mL에 배양액 1mL를 추가하여 25% 추출물을 얻는 식입니다(그림 1).

- 펠릿을 50mL 튜브에 넣고 해당 세포 배양 배지를 추가합니다. 튜브를 37°의 인큐베이터에 24시간 동안 일정한 회전으로 놓습니다.

그림 1: 가용성 추출물의 준비 및 희석 계획. 이 그림의 더 큰 버전을 보려면 여기를 클릭하십시오.

3. 생체 재료 추출물을 사용한 세포 배양

- 세포 현탁액을 준비하고, 실험에 필요한 세포의 수에 따라 멀티웰 플레이트와 같은 적절한 세포 용기에 플레이트한다.

- 80%에서 90%의 합류점으로 원하는 세포의 플라스크로 시작합니다.

- 세포 배양 배지를 버리고, 인산염 완충 식염수 (PBS)로 세척하고, 트립신 EDTA (75cm2 세포 배양 플라스크에 대해 1 내지 2 mL)로 세포를 분리한다.

- 세포 배양 배지 (75cm2 세포 배양 플라스크에 대해 2 내지 4 mL)를 첨가하고, 세포 현탁액을 튜브로 옮기고, 200 x g 에서 5 분 동안 원심분리한다.

- 펠렛을 알려진 부피의 세포 배양 배지에 현탁시킵니다.

참고: 이 프로토콜은 부착 세포 배양의 사용을 위해 설계되었습니다. 그러나 현탁 세포 배양과 함께 작동하도록 간단한 적응을 할 수 있습니다. - 혈구계에서 세포를 세고 세포 현탁액의 세포 농도를 계산합니다.

- 결정된 양의 세포 현탁액을 배양액에 현탁하고 멀티웰 디쉬로 옮깁니다. 파종 밀도의 기준 값으로 5 – 20 x 105 cells/cm2를 고려하십시오.

알림: 적절한 셀 수는 셀 유형 및 셀 특성, 즉 셀 배가 시간에 따라 계산해야 합니다.

- 세포가 부착될 수 있도록 세포를 24시간 동안 인큐베이션한다.

- 이 기간이 지나면 가용성 추출물을 배양 플레이트에 투여합니다.

- 세포 배양 배지를 흡인합니다.

- 앞에서 설명한 대로 농도 순서에 따라 각 웰에 생체 재료의 추출물을 추가합니다. 새로운 세포 배양 배지를 대조군 웰에 추가합니다.

- 플레이트를 24시간 이상 배양합니다.

참고: 음성 대조군은 배양 배지에서 유지되는 처리되지 않은 세포에 해당하는 각 분석에서 수행해야 합니다. 배양 시간은 연구 목표에 따라 선택할 수 있습니다.

4. 대사 활성의 평가

- 생체 재료 추출물과 함께 세포를 배양한 후 플레이트에서 배지를 흡인하고 각 웰 PBS를 세척합니다.

- 각 웰에 PBS, pH 7.4에서 준비한 0.5mg/mL 3-(4,5-디메틸티아졸-2-일)-2,5-디페닐테트라졸 브로마이드(MTT)의 적절한 부피를 넣습니다.

- 플레이트를 37°C의 어둠 속에서 4시간 또는 하룻밤 동안 배양한다.

- 얻어진 포르마잔 결정을 가용화하기 위해, 이소프로판올 중의 0.04 M 염산 용액의 적절한 부피를 각 웰에 첨가하고, 플레이트를 30분 동안 교반한다.

알림: 우물의 크기에 따라 MTT와 이소프로판올의 양을 조정하십시오. - 필요한 경우 결정이 보이지 않을 때까지 위아래로 피펫팅하여 각 웰의 내용물을 저어주고 균질화합니다.

- 분광광도계에서 620nm 기준 필터를 사용하여 570nm 파장의 흡광도를 정량화합니다.

- 대사 활성을 계산하기 위해, 처리된 세포의 흡광도를 대조 배양물의 흡광도로 나눕니다. 백분율 값을 얻으려면 100을 곱하십시오.

5. 세포사멸 평가

알림: 이 평가를 수행하려면 조건당 최소 10개의6 개 셀을 사용해야 합니다.

- 평가 중인 조건에 따라 적절하게 식별된 원심분리기 튜브를 사용하십시오.

- 생체 재료 추출물과 함께 세포 배양 후 배양 배지를 각 튜브에 수집합니다.

- 세포를 분리하고 세포 현탁액을 각 튜브에 추가합니다.

- 세포 현탁액을 120 x g 에서 5분 동안 원심분리하여 농축한다.

- 펠릿을 PBS로 세척하십시오. PBS를 1,000 x g 에서 5분 동안 원심분리하여 제거하였다.

- PBS 1mL를 넣고 세포 펠릿을 확인된 세포분석 튜브에 옮깁니다.

- PBS를 1,000 x g 에서 5분 동안 원심분리하여 제거하였다.

- 100 μL의 결합 완충액(0.01 M HEPES, 0.14 mM NaCl 및 0.25 mM CaCl2)16과 함께 배양하고 세포막 회복을 위해 세포를 약 15분 동안 휴지시킵니다.

- 형광 표지 Annexin-V 2.5μL와 요오드화 프로피듐 1μL를 실온에서 어두운 곳에서 15분 동안 추가합니다.

- 배양 후 400μL의 PBS를 추가하고 세포분석기에서 분석합니다. 정보의 분석 및 정량화를 위해서는 적절한 소프트웨어를 사용하십시오.

- 살아있는 세포, 세포 사멸, 후기 세포 사멸 / 괴사 및 괴사의 백분율로 결과를 제시합니다.

6. 형태 평가

- 멀티웰 플레이트 내부에 맞는 적절한 크기의 멸균 유리 커버슬립을 선택하십시오.

- 멸균 핀셋을 사용하여 각 슬라이드를 우물에 넣습니다.

- 적절한 농도의 세포 현탁액을 웰 내로 분배하고, 95% 공기 및 5%CO2를 갖는 가습된 분위기 하에 37°C의 인큐베이터에서 밤새 방치한다.

- 앞서 설명한 대로 세포 배양물을 추출물에 노출시킵니다.

- 배지를 흡인하고 PBS로 세척하십시오.

- 커버슬립을 실온에서 건조시킨 다음 커버슬립을 덮을 수 있는 충분한 양의 May-Grünwald 용액을 추가합니다. 3 분 동안 배양하십시오.

- 염료를 제거하고 증류수로 1분간 세척한다.

- 물을 제거하고 커버슬립을 덮을 수 있도록 충분한 양의 Giemsa 용액을 추가합니다. 15 분 동안 배양하십시오.

- 흐르는 물에 커버슬립을 씻으십시오.

- 커버슬립을 슬라이드로 옮깁니다.

- 현미경으로 보십시오. 선택한 배율로 사진을 촬영합니다.

7. 역전사중합효소연쇄반응(RT-PCR)을 통한 세포기능 평가

알림: 이 평가를 수행하려면 조건당 최소 2x106 개의 셀을 사용해야 합니다. 예를 들어, 알칼리성 포스파타제는 치아세포 활성 평가를 위한 관심 유전자로 제시됩니다. 관심있는 다른 유전자는 표 1에서 볼 수 있습니다.

- 위에서 설명한 대로 세포를 플레이트합니다.

참고: 도금된 세포의 농도는 연구 중인 생체 재료의 세포 유형 및 세포 독성에 따라 조정해야 할 수도 있습니다. - 위에서 설명한 대로 가용성 추출물과 함께 배양합니다.

- 세포를 분리하여 앞에서 설명한 바와 같이 현탁액을 얻습니다.

- 세포를 PBS로 2회 세척하고; 이 원심분리기를 200 x g에서 실온에서 5분 동안 처리한다.

- 펠릿을 1 mL의 RNA 정제 용액 (예를 들어, NZYol)에 현탁시키고, 강렬하게 교반하고, 연속적인 피펫팅하여 세포를 용해시킨다.

- 샘플을 실온에서 5분 동안 배양합니다.

- 클로로포름 200 μL를 넣고 튜브를 손으로 15 초 동안 흔든다.

- 실온에서 3 분 동안 배양하십시오.

- 원심분리기는 12,000 x g에서 15분 동안 4°C에서 용해됩니다. 이 원심분리 동안 샘플에서 두 단계가 발생하여 RNA가 수성(상부) 상에 남게 됩니다.

- 수성상을 새 튜브로 제거하고 500μL의 차가운 이소프로판올을 첨가하여 RNA를 침전시킵니다.

- 시료를 실온에서 10분 동안 배양하고, 4°C에서 10분 동안 12,000 x g 에서 원심분리한다.

- 상층액을 제거하고, 펠렛을 7,500 x g 에서 4°C에서 5분 동안 원심분리하여 75% 에탄올 1 mL로 세척한다.

- 에탄올이 증발 할 때까지 펠렛을 실온에서 건조시킨다.

- RNase가 없는 물에 현탁합니다.

- 흡수 분광 광도계를 사용하여 시료의 순도를 정량화하고 측정하며, 파장 260 nm 및 280 nm에서 측정합니다. RNA 순도를 측정하고 순도 비율(A260/280)이 약 2.0인 샘플을 사용합니다.

- 샘플을 -80 ° C에서 보관하십시오.

- 제조업체의 프로토콜17에 따라 RT-PCR을 수행합니다.

참고: 연구 목표에 따라 평가할 특정 마커를 선택합니다.

8. 단백질 동정을 통한 세포 기능 평가

참고: 연구 목표에 따라 평가할 특정 단백질을 선택합니다. 예를 들어, 상아질 시알로프로테인(DSP)은 치아세포 활성 평가를 위한 관심 단백질로 제시됩니다. 관심있는 다른 단백질은 표 1에서 볼 수 있습니다.

- 커버슬립에서 세포를 배양하고 앞에서 설명한 대로 추출물에 노출시킵니다.

- 배양된 세포를 PBS로 세척한다.

- 실온에서 3.7 분 동안 30 % 파라 포름 알데히드로 고정하십시오.

- PBS로 두 번 씻으십시오.

- PBS에서 0.5% 트리톤으로 15분 동안 투과합니다.

- PBS 중의 0.3% 과산화수소로 퍼옥시다아제를 5분 동안 차단한다.

- PBS로 두 번 씻으십시오.

- 0.5% 소혈청알부민(BSA)으로 두 번 씻습니다.

- 45분 동안 2% BSA로 세포 배양을 차단합니다.

- PBS에서 0.5% BSA로 세척하십시오.

- 선별된 단백질에 따른 1차 항체와 함께 실온에서 60분 동안 배양한다.

참고: 이 프로토콜은 1차 항체 DSP(M20) 항체(1:100)와 2차 항체 다클론 토끼 항염소 면역글로불린/HRP(1:100)를 사용합니다. - PBS에서 0.5% BSA로 5회 세척합니다.

- 실온에서 90분 동안 2차 항체와 함께 배양합니다.

참고: PBS에서 0.5% BSA를 사용하여 항체 희석액을 만드십시오. - 각 세척에서 1분 동안 PBS에서 0.5% BSA로 5회 세척합니다.

- 25분 동안 20μL chromogen/mL 기질 농도의 기질 및 발색원 혼합물과 함께 배양합니다.

- PBS에서 0.5% BSA로 두 번 세척합니다.

- 헤마톡실린으로 15분 동안 카운터스테인을 사용합니다.

- 0.037 mol/L 암모니아와 증류수로 5분 동안 세척하여 과잉 염료를 제거합니다.

- 슬라이드에 커버슬립을 장착합니다. 글리세롤을 장착 매체로 사용하십시오.

- 밤새 말리십시오.

- 현미경으로 보십시오. 선택한 배율로 사진을 촬영합니다.

9. Alizarin Red S assay를 통한 광물화 평가

- Alizarin Red S 용액을 40 mM 농도로 준비한다18. 어둠 속에서 12 시간 동안 균질화를 위해 용액을 저어줍니다.

알림: Alizarin Red S 용액 100mL를 준비하려면 빛으로부터 보호되는 초순수에 알리자린 분말 1.44g(분자량: 360g/mol)을 가용화합니다. 이 용액의 경우 pH 값은 매우 중요하며 4.1에서 4.3 사이여야 합니다. - 위에서 설명한 대로 가용성 추출물로 세포 배양을 배양합니다.

- 세포 배양물을 PBS로 세 번 세척합니다.

- 실온에서 15 분 동안 4 % 파라 포름 알데히드로 고정하십시오.

- PBS로 세 번 씻으십시오.

- Alizarin Red Staining 용액으로 염색하여 37°C에서 20분간 암실에 두었다.

- 염색 후, 플레이트를 PBS로 세척하여 과량의 염료를 제거한다.

- 현미경으로 보십시오. 선택한 배율로 사진을 촬영합니다.

- 10%(w/v) 아세트산과 20%(w/v) 메탄올로 구성된 추출 용액을 각 웰에 넣고 실온에서 40분 동안 교반합니다.

- 분광광도계(19)로 490 nm 파장에서의 흡광도를 측정한다.

결과

여기서 대표적인 결과는 치과 용 생체 재료 연구를 나타냅니다. 추출물 방법론을 통해 대사 활성(그림 2), 세포 생존율, 세포 사멸 프로필 및 세포 형태(그림 3), 특정 단백질 발현(그림 4)에 대한 영향과 관련하여 치과 재료에 노출한 후 세포 독성 프로필 및 세포 기능을 얻을 수 있습니다.

MTT 분석은 간단한 방?...

토론

이 프로토콜은 조직과 접촉하는 생체 재료의 시험관 내 세포 독성 평가를 지칭하는 ISO 10993-5를 고려하여 설계되었으며, 생체 적합성을 평가하고 연구 재현성에 기여합니다21. 이것은 과학에서 점점 더 많은 관심사이며, 많은 저자들은 이미 시험관 내 연구 15,22,23,24,25,26,27,28의 실험 설계에서 이러한 권장 사항을 따르고 있습니다....

공개

저자는 경쟁적인 재정적 이해 관계나 기타 이해 상충이 없습니다.

감사의 말

We thank the following for support: GAI 2013 (Faculdade de Medicina da Universidade de Coimbra); CIBB는 전략 프로젝트 UIDB/04539/2020 및 UIDP/04539/2020(CIBB)을 통해 FCT(Foundation for Science and Technology)를 통해 국가 기금으로 자금을 지원받습니다. MDPC-23 세포주를 제공한 University of Michigan Dental School의 Jacques Nör에게 감사드립니다.

자료

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Absolute ethanol | Merck Millipore | 100983 | |

| Accutase | Gibco | A1110501 | StemPro Accutas Cell Dissociation Reagent |

| ALDH antibody | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | SC166362 | |

| Annexin V FITC | BD Biosciences | 556547 | |

| Antibiotic antimycotic solution | Sigma | A5955 | |

| BCA assay | Thermo Scientific | 23225 | Pierce BCA Protein Assay Kit |

| Bovine serum albumin | Sigma | A9418 | |

| CaCl2 | Sigma | 10035-04-8 | |

| CD133 antibody | Miteny Biotec | 293C3-APC | Allophycocyanin (APC) |

| CD24 antibody | BD Biosciences | 658331 | Allophycocyanin-H7 (APC-H7) |

| CD44 antibody | Biolegend | 103020 | Pacific Blue (PB) |

| Cell strainer | BD Falcon | 352340 | 40 µM |

| Collagenase, type IV | Gibco | 17104-019 | |

| cOmplete Mini | Roche | 118 361 700 0 | |

| DAB + Chromogen | Dako | K3468 | |

| Dithiothreitol | Sigma | 43815 | |

| DMEM-F12 | Sigma | D8900 | |

| DNAse I | Roche | 11284932001 | |

| DSP (M-20) Antibody, 1: 100 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | LS-C20939 | |

| ECC-1 | ATCC | CRL-2923 | Human endometrium adenocarcinoma cell line |

| Epidermal growth factor | Sigma | E9644 | |

| Hepes 0.01 M | Sigma | MFCD00006158 | |

| Fibroblast growth factor basic | Sigma | F0291 | |

| Giemsa Stain, modified GS-500 | Sigma | MFCD00081642 | |

| Glycerol | Dako | C0563 | |

| Haemocytometer | VWR | HERE1080339 | |

| HCC1806 | ATCC | CRL-2335 | Human mammary squamous cell carcinoma cell line |

| Insulin, transferrin, selenium Solution | Gibco | 41400045 | |

| May-Grünwald Stain MG500 | Sigma | MFCD00131580 | |

| MCF7 | ATCC | HTB-22 | Human mammary adenocarcinoma cell line |

| Methylcellulose | AlfaAesar | 45490 | |

| NaCl | JMGS | 37040005002212 | |

| Polyclonal Rabbit Anti-goat immunoglobulins / HRP, 1: 100 | Dako | G-21234 | |

| Poly(2-hydroxyethyl-methacrylate | Sigma | P3932 | |

| Putrescine | Sigma | P7505 | |

| RL95-2 | ATCC | CRL-1671 | Human endometrium carcinoma cell line |

| Sodium deoxycholic acid | JMS | EINECS 206-132-7 | |

| Sodium dodecyl sulfate | Sigma | 436143 | |

| Substrate Buffer | Dako | 926605 | |

| Tris | JMGS | 20360000BP152112 | |

| Triton-X 100 | Merck | 108603 | |

| Trypan blue | Sigma | T8154 | |

| Trypsin-EDTA | Sigma | T4049 | |

| β-actin antibody | Sigma | A5316 |

참고문헌

- Williams, D. F. On the mechanisms of biocompatibility. Biomaterials. 29 (20), 2941-2953 (2008).

- Bruinink, A., Luginbuehl, R. Evaluation of biocompatibility using in vitro methods: interpretation and limitations. Advances in Biochemical Engineering/Biotechnology. 126, 117-152 (2012).

- Wataha, J. C. Principles of biocompatibility for dental practitioners. The Journal of Prosthetic Dentistry. 86 (2), 203-209 (2001).

- Mishra, S. F. D. A. CE mark or something else?-Thinking fast and slow. Indian Heart Journal. 69 (1), 1-5 (2016).

- Barbeck, M., et al. Balancing Purification and Ultrastructure of Naturally Derived Bone Blocks for Bone Regeneration: Report of the Purification Effort of Two Bone Blocks. Materials. 12 (19), 3234 (2019).

- Ruzza, P., et al. H-Content Is Not Predictive of Perfluorocarbon Ocular Endotamponade Cytotoxicity in Vitro. ACS Omega. 4 (8), 13481-13487 (2019).

- Coelho, C. C., Araújo, R., Quadros, P. A., Sousa, S. R., Monteiro, F. J. Antibacterial bone substitute of hydroxyapatite and magnesium oxide to prevent dental and orthopaedic infections. Materials Science and Engineering: C. 97, 529-538 (2019).

- Jung, O., et al. Improved In Vitro Test Procedure for Full Assessment of the Cytocompatibility of Degradable Magnesium Based on ISO 10993-5/-12. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 20 (2), 255 (2019).

- Ruzza, P., et al. H-Content Is Not Predictive of Perfluorocarbon Ocular Endotamponade Cytotoxicity in Vitro. ACS Omega. 4 (8), 13481-13487 (2019).

- ISO. I.O. for S. ISO 10993-12:2012 - part 12: Sample preparation and reference materials. ISO. , (2012).

- ISO. I.O. for S. ISO 10993-5:2009 Biological evaluation of medical devices - part 5: Tests for in vitro cytotoxicity. ISO. , (2009).

- Srivastava, G. K., et al. Comparison between direct contact and extract exposure methods for PFO cytotoxicity evaluation. Scientific Reports. 8 (1), 1425 (2018).

- Pusnik, M., Imeri, M., Deppierraz, G., Bruinink, A., Zinn, M. The agar diffusion scratch assay--A novel method to assess the bioactive and cytotoxic potential of new materials and compounds. Scientific Reports. 6, 20854 (2016).

- Spiller, K. L., et al. The role of macrophage phenotype in vascularization of tissue engineering scaffolds. Biomaterials. 35 (15), 4477-4488 (2014).

- Zhou, H., et al. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Evaluation of a Novel Root Repair Material. Journal of Endodontics. 39 (4), 478-483 (2013).

- Bordron, A., et al. The binding of some human antiendothelial cell antibodies induces endothelial cell apoptosis. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 101 (10), 2029-2035 (1998).

- Palmini, G., et al. Establishment of Cancer Stem Cell Cultures from Human Conventional Osteosarcoma. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (116), e53884 (2016).

- Gregory, C. A., Grady Gunn, W., Peister, A., Prockop, D. J. An Alizarin red-based assay of mineralization by adherent cells in culture: comparison with cetylpyridinium chloride extraction. Analytical Biochemistry. 329 (1), 77-84 (2004).

- Cai, S., Zhang, W., Chen, W. PDGFRβ+/c-kit+ pulp cells are odontoblastic progenitors capable of producing dentin-like structure in vitro and in vivo. BMC Oral Health. 16 (1), 113 (2016).

- Paula, A., et al. Biodentine Boosts, WhiteProRoot MTA Increases and Life Suppresses Odontoblast Activity. Materials. 12 (7), 1184 (2019).

- Chander, N. G. Standardization of in vitro studies. Journal of Indian Prosthodontic Society. 16 (3), 227-228 (2016).

- Cavalcanti, B. N., Rode de M, S., França, C. M., Marques, M. M. Pulp capping materials exert an effect on the secretion of IL-1β and IL-8 by migrating human neutrophils. Brazilian Oral Research. 25 (1), 13-18 (2011).

- Chang, S., Lee, S. Y., Ann, H. J., Kum, K. Y., Kim, E. C. Effects of calcium silicate endodontic cements on biocompatibility and mineralization-inducing potentials in human dental pulp cells. Journal of Endodontics. 40 (8), 1194-1200 (2014).

- Daltoé, M. O., Paula-Silva, F. W. G., Faccioli, L. H., Gatón-Hernández, P. M., De Rossi, A., Bezerra Silva, L. A. Expression of Mineralization Markers during Pulp Response to Biodentine and Mineral Trioxide Aggregate. Journal of Endodontics. 42 (4), 596-603 (2016).

- Elias, R. V., Demarco, F. F., Tarquinio, S. B. C., Piva, E. Pulp responses to the application of a self-etching adhesive in human pulps after controlling bleeding with sodium hypochlorite. Quintessence International. 38 (2), 67-77 (2007).

- Huang, G. T. J., Shagramanova, K., Chan, S. W. Formation of odontoblast-like cells from cultured human dental pulp cells on dentin in vitro. Journal of endodontics. 32 (11), 1066-1073 (2006).

- Jafarnia, B., et al. Evaluation of cytotoxicity of MTA employing various additives. Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 107 (5), 739-744 (2009).

- Paranjpe, A., Smoot, T., Zhang, H., Johnson, J. D. Direct contact with mineral trioxide aggregate activates and differentiates human dental pulp cells. Journal of Endodontics. 37 (12), 1691-1695 (2011).

- Spagnuolo, G., et al. In vitro cellular detoxification of triethylene glycol dimethacrylate by adduct formation with N-acetylcysteine. Dental Materials. 29 (8), 153-160 (2013).

- Murray, P. E., García Godoy, C., García Godoy C, F. How is the biocompatibilty of dental biomaterials evaluated. Medicina Oral, Patologia Oral y Cirugia Bucal. 12 (3), 258-266 (2007).

- Hanks, C. T., Wataha, J. C., Sun, Z. In vitro models of biocompatibility: a review. Dental Materials. 12 (3), 186-193 (1996).

- Eid, A. A., et al. In Vitro Biocompatibility and Oxidative Stress Profiles of Different Hydraulic Calcium Silicate Cements. Journal of Endodontics. 40 (2), 255-260 (2014).

- Nocca, G., et al. Effects of ethanol and dimethyl sulfoxide on solubility and cytotoxicity of the resin monomer triethylene glycol dimethacrylate. Journal of Biomedical Materials Research Part B: Applied Biomaterials. 100 (6), 1500-1506 (2012).

- Abuarqoub, D., Aslam, N., Jafar, H., Abu Harfil, Z., Awidi, A. Biocompatibility of Biodentine with Periodontal Ligament Stem Cells: In Vitro Study. Dentistry Journal. 8 (1), 17 (2020).

- Coelho, A. S., et al. Cytotoxic effects of a chlorhexidine mouthwash and of an enzymatic mouthwash on human gingival fibroblasts. Odontology. 108 (2), 260-270 (2020).

- Wang, M. O., et al. Evaluation of the In Vitro Cytotoxicity of Cross-Linked Biomaterials. Biomacromolecules. 14 (5), 1321-1329 (2013).

- Tyliszczak, B., Drabczyk, A., Kudłacik-Kramarczyk, S., Bialik-Wąs, K., Sobczak-Kupiec, A. In vitro cytotoxicity of hydrogels based on chitosan and modified with gold nanoparticles. Journal of Polymer Research. 24 (10), 153 (2017).

- Widbiller, M., et al. Three-dimensional culture of dental pulp stem cells in direct contact to tricalcium silicate cements. Clinical Oral Investigations. 20 (2), 237-246 (2016).

- Pintor, A. V. B., et al. In Vitro and In Vivo Biocompatibility of ReOss in Powder and Putty Configurations. Brazilian Dental Journal. 29 (2), 117-127 (2018).

- Pellissari, C. V. G., et al. In Vitro Toxic Effect of Biomaterials Coated with Silver Tungstate or Silver Molybdate Microcrystals. Journal of Nanomaterials. 2020, 1-9 (2020).

- Collado-González, M., et al. Cytotoxicity and bioactivity of various pulpotomy materials on stem cells from human exfoliated primary teeth. International Endodontic Journal. 50, 19-30 (2017).

- Paula, A., et al. Direct Pulp Capping: Which is the Most Effective Biomaterial? A Retrospective Clinical Study. Materials. 12 (20), 3382 (2019).

- Williams, D. F. There is no such thing as a biocompatible material. Biomaterials. 35 (38), 10009-10014 (2014).

- Schuh, J. C. L. Medical device regulations and testing for toxicologic pathologists. Toxicologic Pathology. 36 (1), 63-69 (2008).

- Pizzoferrato, A., et al. Cell culture methods for testing Biocompatibility. Clinical Materials. 15 (3), (1994).

- Pereira Paula, A. B., et al. Direct pulp capping: what is the most effective therapy? - review and meta-analysis. Journal of Evidence Based Dental Practice. , (2018).

- Caiaffa, K. S., et al. Effect of analogues of cationic peptides on dentin mineralization markers in odontoblast-like cells. Archives of Oral Biology. 103, 19-25 (2019).

- Fujiwara, S., Kumabe, S., Iwai, Y. Isolated rat dental pulp cell culture and transplantation with an alginate scaffold. Okajimas Folia Anatomica Japonica. 83 (1), 15-24 (2006).

- Nakashima, M., et al. Stimulation of Reparative Dentin Formation by Ex Vivo Gene Therapy Using Dental Pulp Stem Cells Electrotransfected with Growth/differentiation factor 11 (Gdf11). Human Gene Therapy. 15 (11), 1045-1053 (2004).

- Narayanan, K., et al. Differentiation of embryonic mesenchymal cells to odontoblast-like cells by overexpression of dentin matrix protein 1. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 98 (8), 4516-4521 (2001).

- Kim, H. J., Yoo, J. H., Choi, Y., Joo, J. Y., Lee, J. Y., Kim, H. J. Assessing the effects of cyclosporine A on the osteoblastogenesis, osteoclastogenesis, and angiogenesis mediated by the human periodontal ligament stem cells. Journal of Periodontology. , (2019).

- Bou Assaf, R., et al. Healing of Bone Defects in Pig's Femur Using Mesenchymal Cells Originated from the Sinus Membrane with Different Scaffolds. Stem Cells International. , (2019).

- He, W., et al. Lipopolysaccharide enhances decorin expression through the toll-like receptor 4, myeloid differentiating factor 88, nuclear factor-kappa B, and mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways in odontoblast cells. Journal of Endodontics. 38 (4), 464-469 (2012).

- Xiong, Y., et al. Wnt Production in Dental Epithelium Is Crucial for Tooth Differentiation. Journal of Dental Research. 98 (5), 580-588 (2019).

- Haruyama, N., et al. Genetic evidence for key roles of decorin and biglycan in dentin mineralization. Matrix Biology. 28 (3), 129-136 (2009).

- Sreenath, T., et al. Dentin Sialophosphoprotein Knockout Mouse Teeth Display Widened Predentin Zone and Develop Defective Dentin Mineralization Similar to Human Dentinogenesis Imperfecta Type III. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 278 (27), 24874-24880 (2003).

- Yang, Y., Zhao, Y., Liu, X., Chen, Y., Liu, P., Zhao, L. Effect of SOX2 on odontoblast differentiation of dental pulp stem cells. Molecular Medicine Reports. 16 (6), 9659-9663 (2017).

- Tao, H., et al. Klf4 Promotes Dentinogenesis and Odontoblastic Differentiation via Modulation of TGF-β Signaling Pathway and Interaction With Histone Acetylation. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 34 (8), 1502-1516 (2019).

- Massa, L. F., Ramachandran, A., George, A., Arana-Chavez, V. E. Developmental appearance of dentin matrix protein 1 during the early dentinogenesis in rat molars as identified by high-resolution immunocytochemistry. Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 124 (3-4), 197-205 (2005).

- Hao, J., Zou, B., Narayanan, K., George, A. Differential expression patterns of the dentin matrix proteins during mineralized tissue formation. Bone. 34 (6), 921-932 (2004).

- Tompkins, K., Alvares, K., George, A., Veis, A. Two related low molecular mass polypeptide isoforms of amelogenin have distinct activities in mouse tooth germ differentiation in vitro. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 20 (2), 341-349 (2005).

- Zhai, Y., et al. Activation and Biological Properties of Human β Defensin 4 in Stem Cells Derived From Human Exfoliated Deciduous Teeth. Frontiers in Physiology. 10, (2019).

- Bègue-Kirn, C., Ruch, J. V., Ridall, A. L., Butler, W. T. Comparative analysis of mouse DSP and DPP expression in odontoblasts, preameloblasts, and experimentally induced odontoblast-like cells. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 106, 254-259 (1998).

- Kikuchi, H., Suzuki, K., Sakai, N., Yamada, S. Odontoblasts induced from mesenchymal cells of murine dental papillae in three-dimensional cell culture. Cell and Tissue Research. 317 (2), 173-185 (2004).

- Li, X., Yang, G., Fan, M. Effects of homeobox gene distal-less 3 on proliferation and odontoblastic differentiation of human dental pulp cells. Journal of Endodontics. 38 (11), 1504-1510 (2012).

- Chen, S., et al. Differential regulation of dentin sialophosphoprotein expression by Runx2 during odontoblast cytodifferentiation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 280 (33), 29717-29727 (2005).

- Narayanan, K., Gajjeraman, S., Ramachandran, A., Hao, J., George, A. Dentin matrix protein 1 regulates dentin sialophosphoprotein gene transcription during early odontoblast differentiation. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 281 (28), 19064-19071 (2006).

- Buchaille, R., Couble, M. L., Magloire, H., Bleicher, F. A substractive PCR-based cDNA library from human odontoblast cells: identification of novel genes expressed in tooth forming cells. Matrix Biology. 19 (5), 421-430 (2000).

- Miyazaki, T., Baba, T., Mori, T., Komori, T. Collapsin Response Mediator Protein 1, a Novel Marker Protein for Differentiated Odontoblasts. Acta Histochemica et Cytochemica. 51 (6), 185-190 (2018).

- Yokoi, M., Kuremoto, K., Okada, S., Sasaki, M., Tsuga, K. Effect of attenuation of fibroblast growth factor receptor 2b signaling on odontoblast differentiation and dentin formation. In Vitro Cellular and Developmental Biology - Animal. 55 (3), 211-219 (2019).

- Tohma, A., et al. Glucose Transporter 2 and 4 Are Involved in Glucose Supply during Pulpal Wound Healing after Pulpotomy with Mineral Trioxide Aggregate in Rat Molars. Journal of Endodontics. , (2019).

- Sueyama, Y., Kaneko, T., Ito, T., Kaneko, R., Okiji, T. Implantation of Endothelial Cells with Mesenchymal Stem Cells Accelerates Dental Pulp Tissue Regeneration/Healing in Pulpotomized Rat Molars. Journal of Endodontics. 43 (6), 943-948 (2017).

- Petersson, U., Hultenby, K., Wendel, M. Identification, distribution and expression of osteoadherin during tooth formation. European Journal of Oral Sciences. 111 (2), 128-136 (2003).

- Couble, M. L., et al. Immunodetection of osteoadherin in murine tooth extracellular matrices. Histochemistry and Cell Biology. 121 (1), 47-53 (2004).

- Buchaille, R., Couble, M. L., Magloire, H., Bleicher, F. Expression of the small leucine-rich proteoglycan osteoadherin/osteomodulin in human dental pulp and developing rat teeth. Bone. 27 (2), 265-270 (2000).

- Salmon, B., et al. Abnormal osteopontin and matrix extracellular phosphoglycoprotein localization, and odontoblast differentiation, in X-linked hypophosphatemic teeth. Connective Tissue Research. 55, 79-82 (2014).

- Liao, C., Ou, Y., Wu, Y., Zhou, Y., Liang, S., Wang, Y. Sclerostin inhibits odontogenic differentiation of human pulp-derived odontoblast-like cells under mechanical stress. Journal of Cellular Physiology. 234 (11), 20779-20789 (2019).

- Deng, X., et al. The combined effect of oleonuezhenide and wedelolactone on proliferation and osteoblastogenesis of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells. Phytomedicine. 153103, (2019).

- Choi, H., Kim, T. H., Yun, C. Y., Kim, J. W., Cho, E. S. Testicular acid phosphatase induces odontoblast differentiation and mineralization. Cell and Tissue Research. 364 (1), 95-103 (2016).

재인쇄 및 허가

JoVE'article의 텍스트 или 그림을 다시 사용하시려면 허가 살펴보기

허가 살펴보기더 많은 기사 탐색

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. 판권 소유