암시적 연관 검사

Overview

출처: 줄리안 윌스 & 제이 반 바벨-뉴욕 대학교

사회 심리학의 핵심 구조 중 하나는 객체 또는 사람에 대한 태도의 개념입니다. 전통적으로 심리학자들은 사람들에게 자신의 믿음, 의견 또는 감정을 스스로 보고하도록 요청함으로써 태도를 측정했습니다. 그러나 이 접근법은 인종적 편견과 같은 사회적으로 민감한 태도를 측정할 때, 사람들이 종종 편견없는 평등주의적 신념을 스스로 보고하도록 동기를 부여받기 때문에(부정적인 연관성을 품고 있음에도 불구하고) 한계가 있습니다. 이러한 사회적 바람직성 편향을 우회하기 위해 심리학자들은 의도적인 통제(및 잠재적 왜곡)에 덜 순종하는 암시적 태도를 측정하기 위한 여러 가지 작업을 개발했습니다.

암시적 협회 테스트( IAT)는 이러한 무의식적인 태도중 가장 영향력 있는 조치 중 하나입니다. IAT는 앤서니 그린발트와 동료들이 1998년 논문에 처음 도입했습니다. 1 이 비디오는 최종 실험에서 사용되는 IAT를 수행하는 방법을 보여 주며, 유럽계 미국인 참가자(명시적 평등주의적 태도를 보고함)는 자신의 인종에 대한 암시적 선호도를 나타낸다.

Procedure

1. 참가자 모집

- 전력 분석을 수행하고 관찰된 효과 크기를 감지한 다음 정보에 입각한 동의를 얻기에 충분한 통계적 힘을 얻을 수 있는 충분한 참가자를 모집합니다.

2. 데이터 수집

- 유쾌한 12 단어의 목록을 조립 - 좋은 - 협회(예 :,행복, 행운, 선물) 불쾌한 - 나쁜 - 협회(예 :증오, 재해, 독)와 12 단어.

- 12 명의 유럽계 미국인과 12 명의 아프리카 계 미국인 얼굴 (절반 남성, 절반 여성)을 턱과 이마에 자른 다.

- 5개의블록(즉,시퀀스)으로 자극 프레젠테이션 스크립트를 만듭니다.

- 스크립트는 (1) 진행 지시에 대한 'SPACEBAR', (2) 'E'가 왼쪽의 앵커를 선택하고 (3) 오른쪽에 있는 앵커를 선택하는 세 개의 키보드 응답만 허용해야 합니다.

- 참가자의 주요 누액을 기록하는 것 외에도 스크립트는 응답 대기시간(즉,제공된 각 자극 프레젠테이션 및 응답 사이의 시간)을 기록해야 합니다.

- 블록 1: 초기 대상 개념 차별. 화면 한쪽에 검은색이 표시되고 흰색이 반대쪽에 표시되도록 레이스 앵커를 설정합니다. 특정 방향은 피사체 간에 균형을 유지해야합니다(즉,피험자의 절반은 왼쪽에 검은색을, 오른쪽에 흰색을 보아야 합니다). 이 블록은 총 40개의 시험으로 구성됩니다: 처음 20개는 연습 시험인 반면, 데이터는 후자의 20번의 시험에서 분석됩니다. 무작위로 샘플링 (교체없이) 각각정확히 두 번 표시되도록 (연습 시험을 위해 한 번, 실제 시험을 위해 한 번). 100 ms, 400 ms 또는 700 ms (무작위로 각 시험 선택)의 재판 간 지연에 의해 각 재판의 표시를 분리합니다.

- 블록 2: 연관된 특성 차별. 즐거운 화면의 한쪽에 표시하고 불쾌한 반대쪽에 표시되도록 valence 앵커를 설정합니다. 이 블록은 블록 1(즉,카운터 밸런싱, 시험 횟수, 재판 간 지연)과 동일한 특성을 가지며, 발렌스 단어(예 :좋은, 나쁜)가 얼굴 대신 표시됩니다.

- 블록 3: 초기 결합 작업입니다. 앞의 블록과 동일한 방향을 사용하여 레이스 및 원자 앵커를 모두 표시합니다(예: Black이 블록 1의 오른쪽에 표시되는 경우 이 블록의 오른쪽에 표시되어야 합니다). 총 40번의 시련을 위해 12개의 얼굴과 12개의 용감한 단어를 각각 두 번 이상 제시한다. 이전 블록에서 동일한 평가판 간 지연을 사용합니다.

- 블록 4: 대상 개념 차별을 역전시켰습니다. 원자 앵커를 제거하고 레이스 앵커를 교체하여 이제 Black이 원래 표시된 화면에 표시됩니다(그리고 그 반대의 경우도 마찬가지입니다). 그렇지 않으면 이 블록은 블록 1의 모든 특성을 유지합니다.

- 블록 5: 결합된 작업을 번복합니다. 이 블록은 레이스 앵커가 블록 4에 있던 것과 동일한 위치에 있다는 점을 제외하면 블록 3과 동일합니다. 블록 3과 5는 참가자 간에 균형을 유지해야 합니다.

- 모든 블록의 경우 참가자에게 연결된 범주에 따라 얼굴/용어를 가능한 한 빨리 분류하도록 지시합니다.

- 컴퓨터 로 관리되는 IAT 작업을 완료한 후 인종 관련 태도와 신념을 측정하는 여러 설문지를 배포합니다.

- 참가자가 개인 정보 보호가 있다는 것을 알 수 있도록 개인 실험실에서 이러한 설문지를 작성하도록 하십시오. 또한 완성된 설문지를 표시되지 않은 봉투에 넣은 후 실험자에게 돌려보내겠다고 알려드립니다.

- 설문 조사에는 흑인과 백인의 인종 개념인 현대 인종차별주의 척도2를대상으로 한 느낌 온도계와 의미론적 차등 측정과 다양성과 차별 척도가 포함되어야 합니다. 3

- 앵커로 다음과 같은 극성 형용사 쌍과 다섯 의미 적 차원의 각각에 대한 7 점 척도를 사용 : 아름다운 - 못생긴, 좋은 나쁜, 즐거운 - 불쾌한, 정직 - 부정직, 좋은 - 끔찍한.

- 참가자에게 이 다섯 가지 의미 체계 치수를 사용하여 네 가지 개체 범주의 항목을 평가하도록 지시합니다.

- 참가자들에게 두 앵커링 형용사가 범주와 무관하다고 판단한 경우 축척 의 중간을 표시하도록 지시합니다.

- 브리핑: 연구를 완료하려면 참가자에게 연구의 정확한 특성에 대해 알려주십시오.

3. 데이터 분석

- 300ms에서 300ms까지 300ms 미만의 반응 횟수와 3000ms에 3000ms 이상의 반응 시간을 다시 코딩하여 이러한 극단적인 관찰이 분석에 지나치게 영향을 미치지 않도록 합니다.

- 반응 시간 데이터가 긍정적으로 왜곡되기 때문에 로그는 모든 반응 시간 데이터를 변환하여 보다 정상적으로 배포되도록 합니다.

- 그런 다음 블록 3의 평균 반응 시간을 블록 5와 비교합니다.

- 이러한 점수를 빼고 IAT 효과에 대한 인덱스를 계산합니다.

- 긍정 점수는흑백(즉,프로-블랙)에 대한 암시적 선호도를 반영하며, 음수 점수는 흰색 대 블랙(예: 프로-화이트)에 대한 암시적 선호도를 반영하는 반면, 0점수는 흑백에 대한 암묵적 선호도를 나타냅니다.

- -3(음수)에서 3(양수)까지의 척도를 사용하여 각 개념의 5차원에 대한 명시적 등급을 평균화하여 의미 체계 차등 점수를 계산합니다.

Results

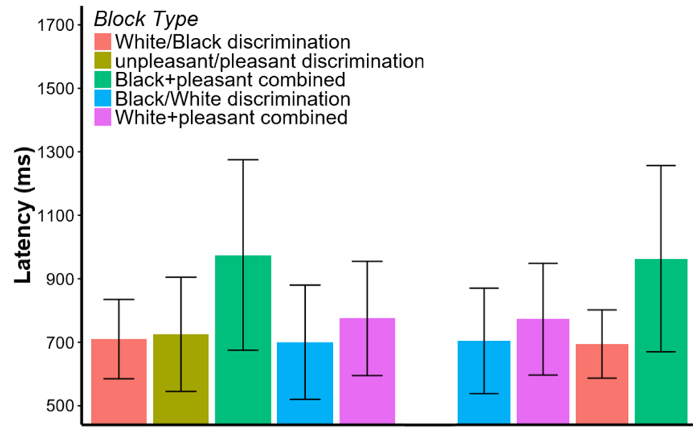

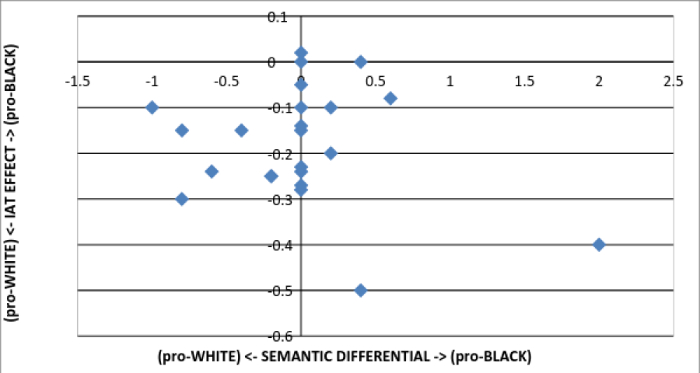

이 절차는 일반적으로 흑백/쾌적한 시험(그림 1)에비해 블랙 / 쾌적한 동안 상당히 느린 응답을 초래한다. 느린 응답은 더 어려운 연결을 반영하는 것으로 해석되기 때문에 이 긴 상대 적 대기 시간(즉,지연)은 Black 을 통해 흰색에 대한 암시적 적 선호도를 시사합니다. 즉, 피사체는 일반적으로 블랙 페이스와 쾌적한 명사를 연결하는 것이 더 어렵다는 것을 알게됩니다. 또한, 화이트 참가자의 응답을 독점적으로 분석할 때, 예를 들어, 그들은 종종 평등주의 적 선호도(즉,흰색 또는 검은색에 대한 선호 없음)를 자체보고할 때, IAT 점수는 흑백에 대한 강한 암시적 선호도를 드러내는점수(그림 2)에도불구하고 종종 자기 보고합니다.

그림 1. 암시적 연결 테스트의 일반적인 결과입니다. 먼저 검은 색 / 쾌적한 블록을 수행 흰색 과목. 평균 반응 시간 점수(변환되지 않은)는 하나의 표준 편차와 동일한 오류 막대가 있는 y축에 표시됩니다. 반응 시간은 분석을 위해 로그 변환되지만 변환되지 않은 점수는 쉽게 해석할 수 있도록 표시됩니다. x축은 이러한 피험자가 이러한 블록에 발생한 순서를 표시합니다. 이 그림은 그린발트, 맥기, 슈워츠에서 채택되었다. 1

그림 2. IAT의 관계는 화이트 참가자 간의 명시적 기본 설정에 점수가 있습니다. IAT 효과 점수는 프로 블랙 기본 설정을 나타내는 긍정 점수, 프로-화이트 기본 설정을 나타내는 음수 점수 및 차등 선호도를 나타내는 0으로 y축에 표시됩니다. 의미 적 차등 점수는 프로 블랙 기본 설정을 나타내는 긍정적 인 점수, 프로 - 화이트 기본 설정을 나타내는 음수 점수, 차등 선호도를 나타내는 0과 함께 x 축에 표시됩니다. 명시적 프로 블랙 또는평등주의(즉,0점) 의미 론치 선호도를 보고하는 거의 모든 백인 참가자도 IAT에 대한 프로 화이트 선호도를 보여줍니다. 이 그림은 그린발트, 맥기, 슈워츠에서 채택되었다. 1

Application and Summary

본 논문 이후 IAT는 성별, 종교, 성별 과 같은 다른 많은 영역에서 편견을 조사하기 위해 확장되었습니다. 4 또한, IAT는 (1) 고정관념으로부터 암묵적 태도를 해리하고, (2) 자/기타를 즐겁고 불쾌한 단어와 짝을 이어 자존감을 측정하고, (3) 아이들의 암묵적 태도를 드러낸다. 경우에 따라 IAT는 차별 및 자살 행동과 같은 자체 보고서 조치보다 더 나은 예측 타당성을 제공합니다. 5

그것이 그렇게 영향력이있는 이유 중 하나는 누구나 여러 버전에 참여할 수있는 프로젝트 암시적 (https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/)이라는 웹 사이트에서 온라인으로 사용할 수 있었기 때문에. 수백만 명의 사람들이 이제 이 법안을 완료했으며, 자체 암묵적 선호도가 테스트를 완료한 다른 사람들과 어떻게 비교되는지에 대한 즉각적인 피드백을 받았습니다. 암시적 편견에 대한 연구는 심리학 분야 밖에서 엄청난 영향을 미쳤으며, 암묵적 편견 교육은 이제 주요 조직, 정부 기관 및 경찰 부서에서 일반적입니다.

References

- Greenwald, A. G., McGhee, D. E., & Schwartz, J. L. (1998). Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the Implicit Association Test. Journal of personality and social psychology, 74, 1464.

- McConahay, J. B., Hardee, B. B., & Batts, V. (1981). Has racism declined in America? It depends on who is asking and what is asked. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 25, 563-579.

- Wittenbrink, B., Judd, C. M., & Park, B. ( 1997). Evidence for racial prejudice at the implicit level and its relationship with questionnaire measures. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72, 262-274.

- Nosek, B. A., Smyth, F. L., Hansen, J. J., Devos, T., Lindner, N. M., Ranganath, K. A., Smith, C.T., et al. (2007). Pervasiveness and correlates of implicit attitudes and stereotypes. European Review of Social Psychology, 18, 36-88.

- Nock, M. K., Park, J. M., Finn, C. T., Deliberto, T. L., Dour, H. J., & Banaji, M. R. (2010). Measuring the suicidal mind: implicit cognition predicts suicidal behavior. Psychological Science, 21, 511-517.

Tags

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. 판권 소유