Motor Learning in Mirror Drawing

Overview

Source: Laboratory of Jonathan Flombaum—Johns Hopkins University

Colloquially, the terms learning and memory encompass a broad range of behaviors and mental systems, everything from learning to tie a shoe to mastering calculus (and a lot in between). Experimental psychologists have divided up learning mechanisms into groups that seem to have different properties, and that seem to rely on different brain systems. A major division is between declarative and non-declarative memory, roughly, the sorts of things a person can express verbally—explicitly, like a birthdate, or what one ate for lunch—and things they cannot quite put into words—things they know implicitly, like how to get home despite not knowing the street names, or how to flip an omelet.

In the domain of non-declarative memory, a crucial kind of learning involves motor learning, sometimes also called procedural memory. Learning to drive a car is a good example. At first it is usually arduous and seems to involve explicit attempts to remember what to do next. Eventually it becomes second nature, though, something that a person just kind of knows how to do—and does better and better with time—but that can be hard to explain to someone else.

Mirror drawing is a common laboratory paradigm for investigating the acquisition of learned motor skills, the kind involved in driving, for example. This video demonstrates standard procedures for mirror drawing.

Procedure

1. Stimuli design

- This experiment requires a mirror that can stand on a table on its own, 2 ft by 2 ft (though larger is fine), as well as a flat rigid surface at least as big as an 8.5 x 11 in piece of paper, that can stand on its own while slightly tilted. A piece of wood with a stand or a piece of foam core is good. We will call this the occluder. The experiment also requires a pencil.

- Place the mirror about 12 in from the edge of a table, standing upright. Place the occluder so that it is about 6 in from the edge of the table, occluding the view of the space between the table and the screen.

- Print out several pieces of white paper with a large star on it and a slightly smaller star within the bigger one (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Star stimulus for use in mirror drawing. The participant’s task will be to trace the star, trying to stay within the boundary of the two outlines. - Place the paper with the star on it between the occluder and the mirror.

2. Running the experiment

- Instruct the participants to place the pencil tip down at any point on the star, between the two borderlines. Without lifting the pencil up, they should trace around the star, coming fully back around while trying to stay within the borders. Count the number of times they cross a border as errors.

- After each session, give the participant a break for at least 10 min.

- Label each piece of paper with the session number (e.g., Day 1, Session 1).

3. Analysis

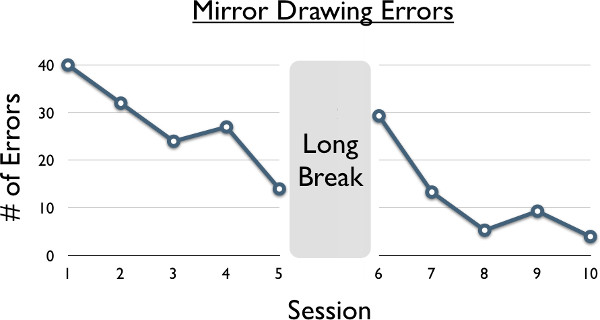

- Record the number of times the participant crossed the borderlines in each experimental session. Generally, the number of errors will decline over time, reflecting motor learning.

Studying motor learning allows for the investigation of, and better understanding into, distinct cognitive mechanisms. For instance, the process of acquiring a new motor skill, such as driving, at first seems arduous but eventually transitions to become second nature.

Experimental psychologists divide up learning and memory processes into subtypes that are associated with different brain systems.

These subtypes distinguish between the knowledge for facts and knowing how to do something. Explicit or declarative memory encompasses factual information, like a birthdate, or what one ate for lunch. Implicit or procedural memory includes things a person cannot quite put into words, like how to get home despite not knowing the street names, or how to skate.

Within the domain of implicit memory lays motor memories. Such memories require motor learning to occur.Learning to walk on a balance beam is a good example.

Using the commonly employed mirror drawing paradigm, this video demonstrates how to setup and perform a study to investigate the acquisition of motor skills, as well as how to analyze and interpret the data.

A mirror drawing experiment requires a pencil, a mirror with dimensions of about 12 inches by 8 inches and that can stand on its own, and an occlude made of wood, foam, or cardboard that can also stand independently. The occluder blocks the direct viewing of the table, requiring the participant to use the mirror to see.

Position the mirror about 12 inches from the edge of a table, standing upright. Next, place the occluder about 6 inches from the edge of the table, making sure that the view of the space in front of the mirror is blocked.

A key component of this experiment is the stimulus, which is a large star shape with a smaller one within it. No matter what the shape is, the stimulus will always consist of a path for the participant to trace.

As the last step before the participant arrives, label the paper with the session number, and place it in the space on the table between the occluder and the mirror.

During each testing session, sit the participant at the table in front of the occluder. Inform him or her that he or she will be tested in multiple sessions with rest breaks in between.

Now instruct the participant to place the pencil tip down at any point on the star, between the two borderlines. Without lifting the pencil up, have him or her trace around the star, coming fully back around, and trying to stay within the borders.

After each session, give the participant a break for at least 10 min.

The analysis for mirror drawing involves counting the number of times the participant crossed the borderlines in each experimental session.

The counted errors are then graphed by plotting the number of errors in a session as a function of session number.

For this participant, overall performance or accuracy in tracing improved over time. Two lines of evidence suggest motor learning occurred.

First, in the session following the long 2-hour break, the participant made fewer errors than in the first session of the day. This savings effect suggests retention of what was learned before the break.

Second, the rate of improvement-the slope of the curve-was steeper after the 2-hour break. Such slopes suggest that the participant learned more quickly, given that learning had previously taken place.

Now that you are familiar with setting up a mirror drawing experiment, let's look at how experimental psychologists use the technique to investigate mechanisms that involve motor learning.

For example, researchers use mirror drawing to investigate the impact of sleep on motor learning. One experiment compared a group of participants that took a nap between sessions against another group that did not sleep during the breaks between sessions.

A decrease in the number of errors for the napping group indicated that sleep promotes retention of recently learned motor skills, as well as a greater rate of improvement.

Perhaps the most famous application of mirror drawing involves the case of patient Henry Gustav Molaison (H.M.) who had most of his hippocampus, a brain region important for the formation of new memories, removed in order to prevent life-threatening seizures.

Fortunately, the surgery worked and his seizure's subsided. Unfortunately, H.M. suffered severe anterograde amnesia making him unable to form new explicit memories.

Amazingly, when it came to mirror drawing, H.M. performed just like everyone else-he showed retained improvements and more rapid improvements on subsequent testing days. This famous study led to the recognition of a distinction between explicit and implicit memory and the brain systems supporting them.

You've just watched JoVE's introduction to mirror drawing. Now you should have a good understanding of how to setup and perform an experiment, as well as analyze and assess the results.

Thanks for watching!

Results

The results are graphed by plotting the number of errors in a session as a function of sequence (Figure 2). Note that performance improved over time. This is evidence of motor learning taking place. The strongest evidence is in the sessions following the long break. Here, the participant’s starting point is better than their starting point before the break. In other words, they retained what they learned, rather than forgetting it. Second, the rate of improvement—the slope of the curve—is steeper after the break. The participant learns more quickly, owing to the learning that has already taken place.

Figure 2: Mirror drawing errors as a function of session number. In this version of the experiment, the participant received a long break of 2 hrs between sessions 5 and 6, instead of the usual 10-min break between the other sessions.

Application and Summary

Mirror drawing has many applications for investigating the mechanisms of motor learning. For example, if a researcher wanted to investigate whether sleep supports motor learning, they might compare a group of participants who complete blocks of mirror drawing sessions, separated by a nap, with another group for whom the sessions are separated by a break without sleep. If the nap group showed fewer errors in the first session after the break than the no-nap group, it would suggest that napping promotes retention of recently learned motor skills. A similar conclusion could be reached if the nap group showed a greater rate of improvement after the nap than the group without the nap.

Perhaps the most famous application of mirror drawing is in the case of patient Henry Gustav Molaison (H.M.). Surgeons removed most of H.M.’s hippocampus in order to prevent life-threatening seizures. Fortunately, the surgery worked, and his seizure’s subsided.

The hippocampus is now known to play a crucial role in the formation of new memories, and H.M. suffered severe anterograde amnesia. He was unable to form new explicit memories. He could not remember events that took place just moments ago, such as a doctor having just visited his hospital room. Amazingly, when it came to mirror drawing, H.M. performed just like everyone else—he improved, and he showed retained improvements and more rapid improvements on subsequent testing days. This famous study, done by psychologist Brenda Milner, in many ways led to the recognition of a distinction between explicit and implicit memory and the brain mechanisms supporting them. For example, follow-up experiments with patients suffering from Alzheimer’s disease—which tends to have its earliest and most severe effects in the hippocampus—have suggested that they, like H.M., often possess a preserved ability for motor learning, despite rampant memory impairment in general.

Skip to...

Videos from this collection:

Now Playing

Motor Learning in Mirror Drawing

Cognitive Psychology

55.4K Views

Dichotic Listening

Cognitive Psychology

26.4K Views

Measuring Reaction Time and Donders' Method of Subtraction

Cognitive Psychology

44.2K Views

Visual Search for Features and Conjunctions

Cognitive Psychology

26.8K Views

Perspectives on Cognitive Psychology

Cognitive Psychology

6.9K Views

Binocular Rivalry

Cognitive Psychology

7.8K Views

Multiple Object Tracking

Cognitive Psychology

7.6K Views

Approximate Number Sense Test

Cognitive Psychology

7.5K Views

Mental Rotation

Cognitive Psychology

13.1K Views

Prospect Theory

Cognitive Psychology

11.2K Views

Measuring Verbal Working Memory Span

Cognitive Psychology

12.4K Views

The Precision of Visual Working Memory with Delayed Estimation

Cognitive Psychology

5.2K Views

Verbal Priming

Cognitive Psychology

14.9K Views

Incidental Encoding

Cognitive Psychology

8.4K Views

Visual Statistical Learning

Cognitive Psychology

7.0K Views

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved