需要订阅 JoVE 才能查看此. 登录或开始免费试用。

Method Article

用于检测按蚊媒介中恶性疟原虫感染的标准膜喂养测定

摘要

标准膜喂养测定(SMFA)被视为评估和鉴定潜在抗疟化合物的金标准。这种人工喂养系统用于感染蚊子,以进一步评估这些化合物对 恶性疟原 虫寄生虫强度和患病率的影响。

摘要

疟疾仍然是全世界最具破坏性的疾病之一,迄今为止,非洲区域仍占全世界所有病例的94%。这种寄生虫病需要原生动物寄生虫、 按蚊 媒介和脊椎动物宿主。 按蚊 属包括500多种,其中60种被称为寄生虫的载体。 疟原虫 属由250种组成,其中48种参与疾病传播。此外, 近年来,恶性疟原 虫已导致撒哈拉以南非洲约99.7%的疟疾病例。

配子细胞是寄生虫性阶段的一部分,在以受感染的人类宿主为食时被雌性蚊子摄入。蚊子中肠的有利环境条件促进了蚊子体内寄生虫的进一步发展。在这里,雌性和雄性配子发生融合,并且运动卵动子起源。卵动体进入蚊子的中肠上皮,成熟的卵泡形成卵囊,卵囊又产生活动孢子体。这些孢子体迁移到蚊子的唾液腺,并在蚊子取血时注射。

出于药物发现目的,在标准膜喂养测定(SMFA)中,蚊子被配子细胞感染的血液人工感染。为了检测蚊子内的感染和/或评估抗疟化合物的功效,雌性蚊子的中肠在感染后被移除并用汞铬染色。该方法用于增强显微镜下卵囊的视觉检测,以准确测定卵囊患病率和强度。

引言

疟疾被称为全球最具破坏性的疾病之一,它仍然对一些国家,特别是非洲地区的国家构成巨大威胁,并占全球约95%的病例1。这种疾病是由原生动物寄生虫引起的,连同其按蚊媒介,这些罪魁祸首会对人类宿主造成巨大伤害2。更具体地说,疟原虫属的恶性疟原虫物种估计占撒哈拉以南非洲疟疾病例的99%1。除此之外,几种主要的按蚊媒介(包括An. gambiae Giles,An. arabiensis Patton,An. coluzzii Coetzee & Wilkerson sp.n.和An. funestus Giles)可能被归咎于全球95%以上的寄生虫传播3,4,5,6,7,8.为了建立理想的寄生虫-媒介陪伴,蚊媒应该对寄生虫敏感并能够传播它9.此外,媒介和寄生虫都应该克服物理障碍,形成完美的感染组合——蚊媒应该能够维持寄生虫的发育,寄生虫应该有能力克服宿主的防御机制10,11。

配子细胞是 恶性疟 原虫的性阶段,在连接载体和寄生虫伙伴方面起着至关重要的作用12。性发育发生在 体内,配子细胞发生描述了成熟配子细胞分化为活动雄性微配子和雌性大配子的过程13。蚊子体内发生的另一个过程是鞭打 - 雄性配子细胞转化为配子并从血餐中摄取的红细胞中出来的过程11。进一步建议通过蚊子中肠环境的有利变化来增强释放过程14。驭毛后,由雄配子和雌配子融合形成受精卵13。从受精卵中,产生一个运动的卵动体,并从血粉移动到蚊子中肠的上皮13。在这里,卵泡成熟,形成卵囊,进而产生运动孢子体13,15。然后,孢子体迁移到蚊子唾液腺,当蚊子从宿主那里获取血粉时,这些孢子体被注射到宿主的血液中15。

疟疾控制干预措施,将病媒控制战略与使用有效的抗疟药物相结合,已成为防治这一疾病的关键15。随着寄生虫和蚊子耐药性的增加,鉴定新型抗疟化合物的紧迫性正在增加16。因此,传递阻断化合物的体内评价很重要16。在开发出这种有效的传播阻断药物后,SMFA已被用于评估这些化合物是否抑制恶性疟原虫在按蚊中的性发育17,18,19。自 1970-1980 年代以来,该测定已获得认可,成为评估传播阻断20,21 的金标准。该检测方法比其他检测方法(如需要专用设备的RT-qPCR)提供了更便宜的替代方案。此外,不需要患者来执行实验。该测定还涉及向雌性蚊子提供配子细胞诱导的血液,然后解剖这些血液以评估是否存在卵囊发育21。这允许配子细胞定量和检测由于化合物22而变形的卵囊。对于被归类为有效的化合物,必须评估患病率(在中肠中至少包含一个卵囊的蚊子比例)和蚊子中肠中的卵囊数量(强度)以评估感染抑制17,21,22。

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

研究方案

有关协议的图示,请参阅 图 1 。比勒陀利亚大学健康科学伦理委员会(506/2018)获得了提取和使用人类血液的伦理许可。

1. 配子细胞培养

注意:在建立SMFA之前,比勒陀利亚大学准备了配子细胞培养物(有关完整方案,请参阅Reader et al.22 )。

- 制备由来自 NF54 寄生虫菌株的 V 期配子细胞组成的配子细胞培养物。

- 确保培养物的配子细胞血症在 1.5% 至 2.5% 之间,在 A+ 男性血清中具有 50% 的血细胞比容,并向其添加新鲜红细胞。

- 将培养物分离到不同的烧瓶中,并在进行SMFA之前48小时为每种处理添加2μM每种化合物。让对照组不治疗。

- 在进行 SMFA 之前不久评估配子细胞培养,以确保雄性配子的脱落,存在 3:1 的雌雄比例。

2. 通过SMFA人工感染蚊子

注意:生物安全:受感染的蚊子应安置在生物安全2级(BSL2)设施中,限制进入。

- 使用口腔吸引器,将 25 只未喂食的雌性 冈比亚蚊 放入 350 mL 喂食杯中。对每个治疗杯做同样的事情,并根据它们是用作对照组还是治疗组清楚地标记杯子。根据所包含的技术重复次数选择每次处理的杯数。

注意:5至7天大的群落蚊子用于典型的传播阻断化合物评估。在喂血前饿死蚊子3-4小时或更长时间将有助于SMFA期间的血液吸收。 - 将玻璃进料器系统连接到水浴,并将温度保持在37°C。

注:玻璃进料器由两个臂组成,它们连接到连接水浴的硅胶管(图2)。喂料器的中空结构允许水通过血液循环并保持血液温度。 - 用自来水冲洗牛肠(或合成膜),然后将其切成适合每个喂食器的碎片。盖住每个喂料器并用松紧带固定膜。

注意:肠道不需要道德许可,因为它是从当地的屠宰场购买的,在那里出售给公众用于食物准备。 - 将感染杯放在喂食器下方,膜铺在杯子网的顶部。

- 向对照杯的喂食器中加入 1 mL 配子细胞感染的血液,向每个相应的复合喂食器和杯中加入化合物,并添加化合物。

- 让蚊子喂食约 40 分钟,喂食器不盖盖子。

注意:喂食在黑暗中的昆虫条件(25°C,80%相对湿度)中进行。喂料器的直径约为 13 毫米。 - 喂食后,从杯子中取出喂食器,冲洗喂食器,并用次氯酸盐处理多余的血液。

- 将所有蚊子放在冰上(1-2分钟)并将未喂食的蚊子与服用血粉的蚊子分开,从而从杯子中取出未喂食的蚊子。寻找肿胀和红色的腹部(指示血液),以区分喂食的、完全充血的蚊子和未喂食的蚊子(图3)。

- 将感染杯放入生物安全室(补充图S1),并为每个杯子提供10%的糖水垫,隔天更换糖水8-10天。

3. 受感染蚊子的制备

注意:协议的这一部分发生在BSL2感染室内。只有经过授权、经过培训的工作人员才能进入饲养受感染蚊子的感染室。蚊子被保存在只包含一个入口点的改良杯子中,当嘴吸气器被移除时,它会自动密封。这些杯子放置在透明的热塑性容器内,以防止逃逸。容器位于双门系统后面的感染室中。必须制定所有必要的协议,以防意外接触受感染的蚊子(补充文件S1)。这些协议因国家而异,取决于机构的要求。

- 在感染喂养后第8-10天,将受感染的蚊子放在冰上并将它们转移到带有70%乙醇的标记管中(保持每个对照组和治疗组的蚊子分开)。

- 确保所有蚊子在离开感染室之前都已死亡。

4. 解剖受感染的蚊子

注意:协议的这一部分在实验室进行。

- 将蚊子转移到衬有滤纸的带标签的培养皿中,将对照组和测试组分开。

- 将一滴磷酸盐缓冲盐水(PBS)放在显微镜载玻片上(根据对照/测试组标记),并将单个蚊子从滤纸转移到PBS。

- 用解剖针固定蚊子的胸部,同时用镊子拉动第 7 个 腹段,从固定的感染标本中取出中肠。

- 随着肠道暴露和可见,寻找Malpighian小管(图4A,B)以区分肠道和卵巢。将其从PBS中取出,将其转移到新的显微镜载玻片上的0.1%汞铬液滴中,并让肠道染色8-10分钟。

- 染色后,将盖玻片放在染色的肠道上,并在明场照明下以20x-40x放大倍率观察肠道(图4C,D)。

- 记录每个对照和治疗组每个中肠卵囊的存在和数量(补充文件S2)。

- 使用公式(1)计算传输阻塞活动:

%待定 (1)

(1)

其中TBA =传播阻断活性(卵囊患病率降低);p = 卵囊患病率;C = 控制;和 T = 治疗。 - 使用公式(2)计算传输减少活动:

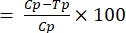

%TRA = (2)

(2)

其中TRA =减少传播活性(卵囊强度降低);I = 卵囊强度;C = 控制;和 T = 治疗。

注意:TBA可能不会显着降低,但在TRA中可能会观察到显着差异,反之亦然。这取决于被评估的化学物质。 - 使用非参数 t 检验(曼-惠特尼)执行统计分析。

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

结果

解剖的对照标本总数为47个,平均患病率为89%,强度为每中肠9.5个卵囊(表1,如之前发表的22)。对于化合物MMV1581558,样本量共达到42个标本,卵囊患病率为36%,平均强度为1.5个卵囊。这表明在所有三个生物学重复中,卵囊患病率降低了58%,TRA降低了82%(表1)。

MMV1581558的%TRA和%TBA均高于50%;因此,这种化合物可被视为阻断和减少传播...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

讨论

为了成功执行此协议,应注意每个步骤,即使它可能是一个乏味而费力的过程。最重要的步骤之一是在开始 SMFA23,24 之前,确保配子细胞培养物质量良好,并且由成熟的配子细胞组成,具有正确的男女比例。在SMFA期间,将配子细胞培养物保持在正确的温度以防止雄配子在进入蚊子之前鞭打也很重要。在建立成功的人工感染中起关键作用的另一个因素是...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

披露声明

作者没有利益冲突需要披露。

致谢

作者要感谢教授。Lyn-Mari Birkholtz和比勒陀利亚大学可持续疟疾控制研究所生物化学,遗传学和微生物学系的Janette Reader博士培养和供应配子细胞培养物。寄生虫菌株是从后一个部门获得的(不是本出版物的一部分)。科学与创新部(DSI)和国家研究基金会(NRF);南非研究教席倡议(UID 64763 至 LK 和 UID 84627 至 LMB);NRF 实践社区(LMB 和 LK 的 UID 110666);南非医学研究理事会战略健康创新伙伴关系(SHIP)也获得了DSI的资金认可。

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

材料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Bovine intestine/ | Butchery | ||

| Compound MMV1581558 | MMV | Pandemic response box | |

| Dissecting needles | WRIM | Custom made | |

| falcon tube | Lasec | ||

| Glass feeders | Glastechniek Peter Coelen B.V. | ||

| Graphpad Prism (8.3.0) | Graphpad | ||

| Mercurochrome | Merck (Sigma-Aldrich) | 129-16-8 | |

| Microscope slides | Merch (Sigma-Aldrich) | S8902 | |

| Parafilm | Cleansafe | ||

| PBS tablets | ThermoFisher Scientific | BP2944 | |

| Perspex biosafety cabinet | Wits University | Made by the contractors at Wits | |

| Plastic cups (350 mL) | Plastic Land |

参考文献

- World Malaria Report. World Health Organization. , Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240040496 (2021).

- Takken, W., Verhulst, N. O. Host preferences of blood feeding mosquitoes. Annual Review of Entomology. 58, 433-453 (2013).

- Gillies, M. T., Coetzee, M. Supplement to the Anophelinae of Africa south of the Sahara Afrotropical region. Publications of the South African Institute for Medical Research. 55, 1(1987).

- Gillies, M. T., De Meillon, B. The Anophelinae of Africa south of the Sahara. Publications of the South African Institute for Medical Research. 54, (1968).

- Antonio-Nkondjio, C., et al. Complexity of the malaria vectorial system in Cameroon: contribution of secondary vectors to malaria transmission. Journal of Medical Entomology. 43, 1215-1221 (2006).

- Sinka, M. E., et al. The dominant Anopheles vectors of human malaria in Africa, Europe and the Middle East: occurrence data, distribution maps and bionomic précis. Parasites and Vectors. 3, 117(2010).

- Coetzee, M., Hunt, R. H., Wilkerson, R., Della Torre, A., Coulibaly, M. B., Besansky, N. J. Anopheles coluzzii and Anopheles amharicus, new members of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Zootaxa. 3619, 246-274 (2013).

- Kyalo, D., Amratia, P., Mundia, C. W., Mbogo, C. M., Coetzee, M., Snow, R. W. A geo-coded inventory of anophelines in the Afrotropical Region south of the Sahara: 1898-2016. Wellcome Open Research. 2, 57(2017).

- Cohuet, A., Harris, C., Robert, V., Fontenille, D. Evolutionary forces on Anopheles: What makes a malaria vector. Trends in Parasitology. 309, (2009).

- Weathersby, A. B. The role of the stomach wall in the exogenous development of Plasmodium gallinaceum as studies by means of haemocoel injections of susceptible and refractory mosquitoes. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 91, 198-205 (1952).

- Ally, A. S. I., Vaughan, A. M., Kappe, S. H. I. Malaria parasite development in the mosquito and infection of the mammalian host. The Annual Review of Microbiology. 63, 195-221 (2009).

- Delves, M. J., et al. Male and female Plasmodium falciparum mature gametocytes show different responses to antimalarial drugs. American Society for Microbiology Journal. , (2013).

- Sinden, R. E. Sexual development of malarial parasites in their mosquito vector. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 75, (1981).

- Garcia, G. E., Wirtz, R. A., Barr, J. R., Woolfitt, A. Xanthurenic acid induces gametogenesis in Plasmodium, the malaria parasite. Journal of Biological Chemistry. 15, 12003-12005 (1998).

- Oaks, S. C. Jr, Mitchell, V. S., Pearson, G. W., et al. Malaria: Obstacles and Opportunities. , National Academic Press. ISBN 0-309-54389-4 (1991).

- Le Manach, C., et al. Identification and profiling of a novel Diazaspirol[3.4]octane chemical series active against multiple stages of the human malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum and optimization efforts. Journal of Medicinal Chemistry. 64, 2291-2309 (2021).

- Cibulskis, R. E., et al. Malaria: global progress 2000-2015 and future challenges. Infect Diseases of Poverty. 5, 61(2016).

- Smith, T. A., Chitnis, N., Briet, O. J., Tanner, M. Uses of mosquito-stage transmission-blocking vaccines against Plasmodium falciparum. Trends in Parasitology. 27, 190-196 (2011).

- Boyd, M. F. Epidemiology: factors related to the definitive host. Malariology. Boyd, M. F. , W.B. Saunders. Philadelphia. 608-697 (1949).

- Ponnudurai, T., van Gemert, G. J., Bensink, T., Lensen, A. H., Meuwissen, J. H. Transmission blockade of Plasmodium falciparum: its variability with gametocyte numbers and concentration of antibody. Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine. 81, 491-493 (1987).

- Rutledge, L. C., Ward, R. A., Gould, D. J. Studies on the feeding response of mosquitoes to nutritive solutions in a new membrane feeder. Mosquito News. 24 (4), (1964).

- Reader, J., et al. Multistage and transmission-blocking targeted antimalarials discovered from the open-source MMV Pandemic Response Box. Nature Communications. 12, 269(2021).

- Bousema, T., et al. Mosquito feeding assays for natural infections. PLoS One. 7 (8), (2012).

- Churcher, T., et al. Measuring the blockade of malaria transmission - An analysis of the standard membrane feeding assay. International Journal for Parasitology. 42, 1037-1044 (2012).

- Medley, G. F., et al. Heterogeneity in patterns of malarial oocyst infections in the mosquito vector. Parasitology. 106, 441-449 (1993).

- Miura, K., et al. Transmission-blocking activity is determined by transmission reducing activity and number of control oocysts in Plasmodium falciparum standard membrane-feeding assay. Vaccine. 34, 4145-4151 (2016).

- Sattabongkot, J., Maneechai, N., Rosenberg, R. Plasmodium vivax: gametocyte infectivity of naturally infected Thai adults. Parasitology. 102 (01), 27-31 (1991).

- Vallejo, A. F., Garcia, J., Amado-Garavito, A. B., Arevalo-Herrera, M., Herrera, S. Plasmodium vivax gametocyte infectivity in sub-microscopic infections. Malaria Journal. 15 (1), 48(2016).

- Ponnudurai, T., Lensen, A. H. W., van Gemert, G. J. A., Bolmer, M. G., Meuwissen, J. H. E. Feeding behavior and sporozoite ejection by infected Anopheles stephensi. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 85, 175-180 (1991).

- Miura, K., et al. Qualification of standard membrane-feeding assay with Plasmodium falciparum malaria and potential improvements for future assays. PLoS One. 8, 57909(2013).

- Griffin, P., et al. Safety and reproducibility of a clinical trial system using induced blood stage Plasmodium vivax infection and its potential as a model to evaluate malaria transmission. PLoS Neglected Tropical Diseases. 10, 0005139(2016).

- Delves, M. J., Sinden, R. E. A semi-automated method for counting fluorescent malaria oocysts increases the throughput of transmission blocking studies. Malaria Journal. 9, 35(2010).

- vander Kolk, M., et al. Evaluation of the standard membrane feeding assay (SMFA) for the determination of malaria transmission-reducing activity using empirical data. Parasitology. 130, 13-22 (2005).

- van der Kolk, M., de Vlas, S. J., Sauerwein, R. W. Reduction and enhancement of Plasmodium falciparum transmission by endemic human sera. International Journal for Parasitology. 36, 1091-1095 (2006).

- Singh, M., et al. Plasmodium's journey through the Anopheles mosquito: A comprehensive review. Biochimie. 181, 176-190 (2021).

- Vos, M. W., et al. A semi-automated luminescence based standard membrane feeding assay identifies novel small molecules that inhibit transmission of malaria parasites by mosquitoes. Scientific Reports. 5, 18704(2015).

- Azevedo, R., et al. Bioluminescence method for in vitro screening of Plasmodium transmission-blocking compounds. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 61, (2017).

- Okell, L. C., Bousema, T., Griffin, J. T., Ouedraogo, A. L., Ghani, A. C., Drakeley, C. J. Factors determining the occurrence of submicroscopic malaria infections and their relevance for control. Nature Communications. 3, 1237(2012).

- Pasay, C. J., et al. Piperaquine monotherapy of drug-susceptible Plasmodium falciparum infection results in rapid clearance of parasitemia but is followed by the appearance of gametocytemia. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 214, 105-113 (2016).

- Stone, W. J., et al. A scalable assessment of Plasmodium falciparum transmission in the standard membrane-feeding assay, using transgenic parasites expressing green fluorescent protein-luciferase. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 210, 1456-1463 (2014).

- Hasan, A. U., et al. Implementation of a novel PCR based method for detecting malaria parasites from naturally infected mosquitoes in Papua New Guinea. Malaria Journal. 8, 182(2009).

- Stone, W. J., et al. The relevance and applicability of oocyst prevalence as a read-out for mosquito feeding assays. Scientific Reports. 3, 3418(2013).

- Marquart, L., Baker, M., O'Rourke, P., McCarthy, J. S. Evaluating the pharmacodynamic effect of antimalarial drugs in clinical trials by quantitative PCR. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 59, 4249-4259 (2015).

- McCarthy, J. S., et al. tolerability, pharmacokinetics, and activity of the novel long-acting antimalarial DSM265: a two-part first-in-human phase 1a/1b randomised study. TheLancet Infectious Diseases. 17, 626-635 (2017).

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

转载和许可

请求许可使用此 JoVE 文章的文本或图形

请求许可探索更多文章

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

版权所属 © 2025 MyJoVE 公司版权所有,本公司不涉及任何医疗业务和医疗服务。