Thinking Too Much Impairs Decision-Making

Przegląd

Source: Peter Mende-Siedlecki & Jay Van Bavel—New York University

When we are considering a tough choice between two or more attractive options, we often end up actively weighing the pros and cons of each alternative. By reflecting on their advantages and disadvantages, we attempt to fit a complex, subjective decision into an orderly set of criteria. However, research in psychology suggests that this sort of introspective approach might not always yield the most optimal outcomes.1

In other words, sometimes thinking hard about a problem or a choice may not produce desired results. Similar results have been demonstrated in the domains of emotion (participants who ruminated about a bad mood showed less mood improvement than participants who were merely distracted from their mood;2 and memory (verbalizing the details of a criminal’s face led to poorer recognition in a photo array of possible suspects.3 Furthermore, Wilson and colleagues observed that reflecting on the reasons behind one’s attitudes (i.e., considering “why” one feels a certain way) can disrupt the consistency between attitudes and behavior, and can even change attitudes.4

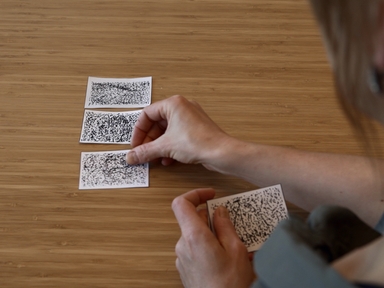

Why might this be the case? Wilson and colleagues speculate that often we don’t typically have a very good understanding of why we actually feel the way we do.5 Upon introspection of our feelings, we may hone in on irrelevant but salient details that may offer plausible explanations, but may also have little direct influence on our actual attitudes. Wilson and Schooler devised an experiment designed to test this possibility in the domain of subjective preferences. Specifically, they compared participants’ evaluations of a series of jams with experts’ evaluations, and tested whether asking participants to analyze the reasons for their choices would have a negative impact on their evaluations.

Procedura

1. Participant Recruitment

- Conduct a power analysis and recruit a sufficient number of participants and obtain informed consent from the participants.

- Gather two experimenters: One to administer the jam taste test, and another (blind to condition) to obtain participants’ ratings of each jam.

- Recruit volunteers for a study entitled "Jam Taste Test". Instruct volunteer subjects not to eat anything for 3 hrs prior to the study.

2. Data Collection

Wyniki

In the original Wilson and Schooler investigation, the authors observed that asking participants to think about their reasons for their evaluations did indeed change their ratings of the set of jams, as compared to the ratings given by control participants.

Critically, when comparing against the objective criterion (e.g., experts ratings), the average correlation between “reasons-analysis” participants’ ratings and experts’ ratings was significantly lower than

Wniosek i Podsumowanie

Based on these results, the authors concluded that while the control participants formed jam preferences that were very similar to an objective criterion of quality (e.g., experts’ ratings), participants who spent time deliberating about the reasons supporting their evaluations showed much less correspondence with this criterion. The authors suggest that these participants’ preferences were influenced by the process of introspection, which likely caused them to focus on salient, but ultimately irrele

Odniesienia

- Wilson, T. D., & Schooler, J. W. (1991). Thinking too much: introspection can reduce the quality of preferences and decisions. Journal of personality and social psychology, 60(2), 181.

- Morrow, J., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (1990). Effects of responses to depression on the remediation of depressive affect. Journal of personality and social psychology, 58(3), 519.

- Schooler, J. W., & Engstler-Schooler, T. Y. (1990). Verbal overshadowing of visual memories: Some things are better left unsaid. Cognitive psychology, 22, 36-71.

- Wilson, T. D., Dunn, D. S., Kraft, D., & Lisle, D. J. (1989). Introspection, attitude change, and attitude-behavior consistency: The disruptive effects of explaining why we feel the way we do. Advances in experimental social psychology, 22, 287-343.

- Nisbett, R. E., & Wilson, T. D. (1977). Telling more than we can know: Verbal reports on mental processes. Psychological review, 84, 231-259.

- Lisle, D., Schooler, J., Hodges, S. D., Klaaren, K. J., & LaFleur, S. J. (1993). ‘Introspecting about reasons can reduce post-choice satisfaction. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 19, 331-39.

- Wilson, T. D., & Gilbert, D. T. (2003). Affective forecasting. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 35, 345-411.

Przejdź do...

Filmy z tej kolekcji:

Now Playing

Thinking Too Much Impairs Decision-Making

Social Psychology

11.0K Wyświetleń

Thinking Too Much Impairs Decision-Making

Social Psychology

11.0K Wyświetleń

Experimental Research Examining How People Can Cope with Uncertainty Through Soft Haptic Sensations

Social Psychology

9.0K Wyświetleń

Assessment of Social Cognition in Non-human Primates Using a Network of Computerized Automated Learning Device (ALDM) Test Systems

Social Psychology

12.0K Wyświetleń

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. Wszelkie prawa zastrzeżone