A subscription to JoVE is required to view this content. Sign in or start your free trial.

Method Article

A Standardized Method for Measuring Internal Lung Surface Area via Mouse Pneumonectomy and Prosthesis Implantation

In This Article

Summary

Internal lung surface area (ISA) is a critical criterion for assessing lung morphology and physiology in lung diseases and injury-induced alveolar regeneration. We describe here a standardized method that can minimize the measurement bias for ISA in both lung pneumonectomy and prosthesis implantation mouse models.

Abstract

Pulmonary morphology, physiology, and respiratory functions change in both physiological and pathological conditions. Internal lung surface area (ISA), representing the gas-exchange capacity of the lung, is a critical criterion to assess respiratory function. However, observer bias can significantly influence measured values for lung morphological parameters. The protocol that we describe here minimizes variations during measurements of two morphological parameters used for ISA calculation: internal lung volume (ILV) and mean linear intercept (MLI). Using ISA as a morphometric and functional parameter to determine the outcome of alveolar regeneration in both pneumonectomy (PNX) and prosthesis implantation mouse models, we found that the increased ISA following PNX treatment was significantly blocked by implantation of a prosthesis into the thoracic cavity1. The ability to accurately quantify ISA is not only expected to improve the reliability and reproducibility of lung function studies in injured-induced alveolar regeneration models, but also to promote mechanistic discoveries of multiple pulmonary diseases.

Introduction

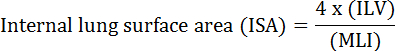

The fundamental function of the lung is the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between blood vessels and the atmosphere. Lung diseases such as bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and acute respiratory infections, result in decreased ISA2. Researchers studying lung disease have developed several quantitative methods to evaluate morphological changes in lungs, including MLI, ILV, number of gas exchange units, ISA, and lung tissue compliance2,3. Pioneering studies by Weibel et al.4 and Duguid et al.5 together established that ISA can be used as a direct measure of lung gas-exchange capacity in human lungs and can be used as a criterion to determine emphysema severity. A number of studies published in the last five years have used lung morphological parameters (e.g., ISA and MLI) to assess morphological and functional changes in the lungs of mice during development6 and during recovery from injury PNX1,7. ISA is calculated using Equation 18,9:

, where ILV is the internal lung volume and MLI is an intermediary parameter that represents the pulmonary peripheral airspace size10.

PNX, the surgical removal of one or more lung lobes, has been widely reported to induce alveolar regeneration in many species, including humans11, mice1, dogs12, rats13, and rabbits14,15. A study of mice lungs at fourteen days post-PNX showed that both the expansion of pre-existing alveoli and the de novo formation of alveoli contribute to the restoration of ISA, ILV, and the number of alveoli in the remaining lung tissues1. We and others have shown that the insertion of materials such as sponge, wax, or a custom-shaped prosthesis into the empty thoracic cavity following PNX (i.e., prosthesis implantation) impairs alveolar regeneration. It is now firmly established that mechanical force functions as one of the most important factors for initiating alveolar regeneration1,16,17. Such studies have highlighted the effectiveness of using ISA values from PNX-treated and Prosthesis-implanted lungs as a criterion to quantitatively evaluate alveolar regeneration.

Observer bias is known to significantly influence measured values for lung morphological parameters (e.g., MIL and ILV). Standardized protocols can be used to obviate this bias in determining both ILV and MLI, which are the two parameters used in the calculation of ISA. Here, we provide highly-detailed, standardized protocols for measuring these lung parameters. Importantly, the ability to accurately quantify ISA promises to improve the reliability and reproducibility of studies of lung function in injury-induced alveolar regeneration models and should facilitate mechanistic discoveries in multiple pulmonary diseases.

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Protocol

All procedures used in this protocol were carried out in accordance with the recommendations in the Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institute of Biological Sciences, Beijing. 8 week-old CD-1 male mice were housed in a specific pathogen free (SPF) facility until the experiments were conducted. Surgeries were performed using completely anesthetized mice (i.e., without any toe pinch responses). After surgery, mice were kept in a warm, humid room with sufficient food and fresh water. Mice were sacrificed using an overdose of anesthetic delivered by intraperitoneal injection.

1. Mouse PNX Surgery

- Fully anesthetize the mice with sodium phenobarbital (120 mg / kg body weight) and buprenorphine (0.1 mg / kg body weight) via intraperitoneal (I.P.) injection. Perform surgery when mice no longer react to toe pinching.

- Remove hair on the left thorax of the mice with chemical depilatory treatment (~3 x 3 cm2 area).

- Secure each mouse on an intubation platform with its ventral side facing the operator (Figure 1A).

- Pull out the mouse tongue and illuminate the vocal cords with a small animal laryngoscope containing a notch for guiding catheters18 (Figure 1A).

- Distinguish the vocal cords by observing the movements of the vocal cords during breathing. Gently insert a 20 G intravenous intubation cannula into the trachea at an anterior angle19.

- Place mice in a right lateral recumbent position and connect the cannula to a mechanical ventilator (e.g., pressure controlled; see the Table of Materials). Check the insertion of the cannula into the trachea by observing the breathing movements of the mouse chest (Figure 1B).

- Set the inspiratory pressure of the ventilator to 12 cm H2O and set the respiratory rate to 120 breaths per min (Figure 1B).

- Decontaminate the skin in the surgical area with betadine and 70% ethanol.

- Make a 2 - 3 cm posterolateral thoracotomy incision in the space at the 5th intercostal space, cut through skin and muscles with Noyes Spring Scissors (cutting edge: 14 mm; tip diameter: 0.275 mm) (Figure 2B, C). Surgical instruments used for thoracotomy procedure are sterilized prior to use.

- Make a 1.5 cm incision at the 5th intercostal space to expose the left lung (Figure 2D, E). During the operation, use a high temperature cauterizer to stop bleeding.

- Lift one-third of the left lung lobe from the chest with blunt tip forceps (Figure 2F), and then use a cotton swab to pull out the entire left lung (Figure 2G).

- Identify the pulmonary artery and bronchi of the left lung lobe (Figure 2G).

- Tightly ligate the bronchi and vessels at the hilum with a silk surgical suture and cut out the left lung lobe at 3 - 4 mm from the ligation (Figure 2H, I).

NOTE: Be careful not to cut off the suture knots on the left hilum, which can cause pneumothorax (i.e., air or gas in the cavity of the thorax). - Close the chest wall with 1 suture, and then stitch the muscle layer and the skin layer sequentially, using 5 - 6 interrupted sutures. Leave a 3 - 4 mm gap between each suture (Figure 2M, 2N).

NOTE: Keep the surgical suture needle away from the heart; inadvertent cardiac puncture will result in immediate death. - Disinfect the surgical area with povidone-iodine.

- After the surgical operation, place the mouse on a 38 °C thermal pad and connect the mouse to the ventilator until spontaneous breathing movements commence (Figure 2O).

2. Prosthesis Implantation

- Perform steps 1.1 - 1.13 of the PNX procedure (that is, up to the point when the left lung lobe of the mouse is removed).

- Clamp the center of the silicone prosthesis (customer made, 12 mm in length, 3 mm in thickness, 7 mm in width, 0.2 g, ellipsoid-shape) using blunt forceps (Figure 2J). Sterilize silicone prosthesis prior to insertion.

- Hold the rib with forceps with one hand to expose the thoracic cavity, and then insert the prosthesis into the left empty thoracic cavity with another hand.

NOTE: The insertion angle is approximately 45 degrees between the frontal plane of the prosthesis and the thoracic surface (Figure 2K, L). Be very gentle when inserting the prosthesis. Excessive force will result in pleural rupture. - Adjust the orientation of the prosthesis with blunt forceps to ensure that the prosthesis occupies the left empty thoracic cavity.

- Perform steps 1.14 - 1.16 of the mouse PNX procedure.

3. Measurement of ILV

- Prepare a custom device ("inflation tube") that consists of a plunger removed from a disposable serological pipette (10 mL), a 40 cm long flexible tube with a needle adapter, a flow rate control valve, and an 18 G needle. After assembly, secure the pipette on a board with tape (Figure 3A). The distance between the top of the pipette and the experimental bench must be at least 30 cm.

- Prepare fresh 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) fixation solution by dissolving 20 g PFA in 500 mL pre-heated 1x phosphate buffered saline (PBS) in a 55 °C water bath, shaking manually once every 10 min until the solution is clear. After cooling to room temperature, filter the solution with a 0.45 µm filter.

CAUTION: Wear appropriate personal protective equipment (PPE) when handling PFA. - Sacrifice mice with an overdose injection of anesthetic (0.8% phenobarbital sodium, 1,000 U/mL heparin).

- Secure each mouse on a polystyrene dissection plate and spray it with 70% alcohol.

- Carefully open the mouse chest and cut out the sternum using scissors to thoroughly expose the lung lobes.

- Remove excessive tissue using scissors to expose the trachea. Make sure to separate the trachea from the esophagus.

- Cut the abdominal aorta and insert a 25-gauge needle into the right ventricle of heart; connect the needle to a 20 mL syringe prior to this insertion. Slowly push 1x PBS into the heart to remove blood cells until lungs turn white. Typically, 5 - 10 mL PBS is required to clear the pulmonary blood vessels.

- Fill the custom-constructed inflation tube with 4% fresh PFA and remove all the bubbles from the inflation tube.

- Insert the 18-gauge needle of the inflation tube into the trachea and clip the trachea with vessel clips to avoid fluid leakage.

- Inflate lungs with 4% PFA at a constant transpulmonary pressure of 25 cm/H2O2,20. Incubate the lungs at room temperature for 2 h to achieve fully expanded lungs. This "pre-fix" step is critical for preserving lung morphology.

- By monitoring the inflation tube, record the value of the initial 4% PFA volume and record the final volume. The internal lung volume equals the initial 4% PFA volume minus the final 4% PFA volume.

- Ligate the trachea and using scissors, gently dissect out the lungs (keeping the lungs intact) from surrounding connective tissues. Be very gentle to avoid damaging the lungs.

- Incubate the lungs in a 50-mL conical tube filled with 4% PFA for 12 h at 4 °C with gentle shaking on an shaker (50 rpm). Proceed to tissue processing and staining (see section 4).

4. Tissue Embedding, Sectioning, and Hematoxylin & Eosin (H&E) Staining

- After fixation, use Noyes Spring Scissors to trim the heart and excessive connective tissues off the lungs. Gently separate the individual lung lobes by cutting off the bronchus that connects the lung lobes to the trachea.

- Extensively wash the lung lobes 3 - 4 times in 50 mL 1x PBS (30 min/wash) on an orbital shaker (50 rpm).

- Following the final wash, cryoprotect the lung lobes by immersing them in a 30% sucrose solution (in 1x PBS) at 4 °C until the tissue sinks to the bottom of the 50-mL conical tubes (approximately 12 h).

- Prior to embedding and cryosectioning the tissues, remove the lung lobe samples from the tubes with forceps, retain the accessory lobes for the histological analysis, dab the remaining sucrose solution from the surface of the accessory lobe samples, and then thoroughly immerse the sample into a Petri dish containing optimal cutting temperature (O.C.T) compound for approximately 30 min.

- Freeze the O.C.T-embedded accessory lobe samples in liquid nitrogen using cryomolds. Position the largest surface area of the lobe parallel to the bottom of the mold.

- Prepare a total of three 10-µm-thick sections for each sample during cryosectioning for histological analysis. Discard the first 1 mm of tissue, collect one 10-µm-thick section, discard 0.5 mm of tissue, collect another section, discard 0.5 mm of tissue, and collect the third (final) section.

- Air dry the sections for 1 h before performing H&E staining.

- Perform H&E staining

- Wash the sections in 3 - 4 changes of tap water and then stain the sections in fresh hematoxylin for 2 min; rinse the section under running tap water; immerse the section two times in a 1% HCl-70% ethanol solution to remove excess hematoxylin.

- Stain the section in fresh eosin for 3 min; dehydrate the sections with two successive 30 s washes in 95% ethanol and two 30 s washes with 100% ethanol; clear the sections in xylene for 30 s, repeat the clearing step once in fresh xylene; mount the slides with mounting medium using glass coverslips.

5. Quantification of MLI

- Acquire digital images of the H&E stained accessory lobe sections (20X magnification) using a bright-field microscope.

- To quantify the MLI, select a total of 15 non-overlapping views (1,000 µm x 1,000 µm) randomly from the suitable areas (without arteries and veins, major airways, and alveolar ducts) of 3 sections.

- Place a grid with 10 evenly-distributed vertical lines and 10 equally-distributed horizontal lines of defined length (1,000 µm) on the chosen areas of view using a ruler tool; each line is thus spaced 100 µm apart (Figure 4B).

- Define the value of one intercept as the linear length between two adjacent alveolar epithelia. Measure the values of all intercepts along each 1,000 µm length line.

- For each grid, quantify the values of all intercepts among the 10 horizontal 1,000 µm length lines and the 10 vertical 1,000 µm length lines.

NOTE: MLI is the average value of the intercept lengths from a total of 15 grids analyzed from among the 3 sections prepared for each of the accessory lobes.

6. Calculation of ISA

- Calculate the ISA using Equation 1 (see the Introduction). Refer to section 3 for the measurement of ILV and refer to section 5 for the quantification of MLI.

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Results

We performed here an experiment with a PNX-treated group and a prosthesis implantation (Prosthesis-implanted) group. These groupings are the same as the groupings used in a previously-published study from our research group14.

The mouse PNX and prosthesis implantation procedures are shown in Figure 2. 8 week-old CD-1 male mice are used for the surgeries and for the quantifica...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Discussion

In this protocol, we provide detailed descriptions about the measurement of pulmonary parameters after mouse left lung PNX and prosthesis implantation. ISA is now considered to be a key metric for the assessment of respiratory function in many pulmonary diseases and in injury-induced alveolar regeneration. However, although the pulmonary research community is in agreement about the utility of ISA as a useful metric, to date, there has been little consideration of the standardization of the measurement of ILV and MLI, the...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge the National Institute of Biological Sciences, Beijing for the assistance. This work was supported by Beijing Municipal Natural Science Foundation (No. Z17110200040000).

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Low cost cautery kit | Fine Science Tools | 18010-00 | |

| Noyes scissors | Fine Science Tools | 15012-12 | |

| Standard pattern forceps | Fine Science Tools | 11000-12 | |

| Castroviejo Micro Needle Holders | Fine Science Tools | 12060-01 | |

| Vessel clips | Fine Science Tools | 18374-44 | |

| I. V. Cannula-20 gauge | Jinhuan Medical Product Co., LTD. | 29P0601 | |

| Surgical suture | Jinhuan Medical Product Co., LTD. | F602 | |

| Mouse intubation platform | Penn-Century, Inc | Model MIP | |

| Small Animal Laryngoscope | Penn-Century, Inc | Model LS-2-M | |

| TOPO Small Animal Ventilator | Kent Scientific | RSP1006-05L | |

| Thermal pad | Stuart equipment | SBH130D | |

| Pentobarbital sodium salt | Sigma | P3761 | |

| Heparin sodium salt | Sigma | H3393 | |

| Hematoxylin Solution | Sigma | GHS132 | |

| Eosin Y solution, alcoholic | Sigma | HT110116 | |

| 10 mL Pipette | Thermo Scientific | 170356 | |

| Paraformaldehyde | Sigma | P6148 | |

| O.C.T Compound | Tissue-Tek | 4583 | |

| cryosection machine | Leica | CM1950 | |

| Disposable Base Molds | Fisher HealthCare | 22-363-553 | |

| 18 gauge needle | Becton Dickinson | 305199 | |

| Povidone iodine | Fisher Scientific | 19-027132 | |

| 70% ethanol | Fisher Scientific | BP82011 | |

| Infusion sets for single use | Weigao | SFDA 2012 3661704 | |

| Phosphate buffered saline | Gibco | 10010023 | |

| Tapes | 3M Scotch | 8915 | |

| Cotton pad | Vinda | Dr.P | |

| Silicone prosthesis | Custom made | ||

| Brightfield microscope | Olympus | VS120 | |

| Ruler tool | Adobe Photoshop |

References

- Liu, Z., et al. MAPK-Mediated YAP Activation Controls Mechanical-Tension-Induced Pulmonary Alveolar Regeneration. Cell Rep. 16 (7), 1810-1819 (2016).

- Thurlbeck, W. M. Internal surface area and other measurements in emphysema. Thorax. 22 (6), 483-496 (1967).

- Knudsen, L., Weibel, E. R., Gundersen, H. J. G., Weinstein, F. V., Ochs, M. Assessment of air space size characteristics by intercept (chord) measurement: an accurate and efficient stereological approach. J Appl Physiol. 108 (2), 412-421 (2010).

- Weibel, E. R. Morphometry of the Human Lung. , Springer-Verlag. Berlin Heidelberg. (1963).

- Duguid, J. B., Young, A., Cauna, D., Lambert, M. W. The internal surface area of the lung in emphysema. J Pathol Bacteriol. 88, 405-421 (1964).

- Branchfield, K., et al. Pulmonary neuroendocrine cells function as airway sensors to control lung immune response. Science. 351 (6274), 707-710 (2016).

- Ding, B. -S., et al. Endothelial-derived angiocrine signals induce and sustain regenerative lung alveolarization. Cell. 147 (3), 539-553 (2011).

- Dunnill, M. S. Quantitative methods in the study of pulmonary pathology. Thorax. 17 (4), 320-328 (1962).

- Weibel, E. R., Gomez, M. Architecture of the human lung. Use of quantitative methods establishes fundamental relations between size and number of lung structures. Science. 137 (3530), 577-585 (1962).

- Thurlbeck, W. M. The internal surface area of nonemphysematous lungs. Am Rev Respir Dis. 95 (5), 765-773 (1967).

- Butler, J. P., et al. Evidence for adult lung growth in humans. N Engl J Med. 367 (16), 244-247 (2012).

- Hsia, C. C. W., Herazo, L. F., Fryder-Doffey, F., Weibel, E. R. Compensatory lung growth occurs in adult dogs after right pneumonectomy. J Clin Invest. 94 (1), 405-412 (1994).

- Thurlbeck, S. W. M. Pneumonectomy in Rats at Various Ages. Am Rev Respir Dis. 120 (5), 1125-1136 (1979).

- Cagle, P. T., Langston, C., Thurlbeck, W. M. The Effect of Age on Postpneumonectomy Growth in Rabbits. Pediatr Pulmonol. 5 (2), 92-95 (1988).

- Langston, C., et al. Alveolar multiplication in the contralateral lung after unilateral pneumonectomy in the rabbit. Am Rev Respir Dis. 115 (1), 7-13 (1977).

- Cohn, R. Factors Affecting The Postnatal Growth of The Lung. Anatomical Record. 75 (2), 195-205 (1939).

- Hsia, C. C., Wu, E. Y., Wagner, E., Weibel, E. R. Preventing mediastinal shift after pneumonectomy impairs regenerative alveolar tissue growth. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 281 (5), L1279-L1287 (2001).

- Das, S., MacDonald, K., Chang, H. -Y. S., Mitzner, W. A simple method of mouse lung intubation. J Vis Exp. (73), e50318(2013).

- Liu, S., Cimprich, J., Varisco, B. M. Mouse pneumonectomy model of compensatory lung growth. J Vis Exp. (94), (2014).

- Silva, M. F. R., Zin, W. A., Saldiva, P. H. N. Airspace configuration at different transpulmonary pressures in normal and paraquat-induced lung injury in rats. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 158 (4), 1230-1234 (1998).

- Yilmaz, C., et al. Noninvasive quantification of heterogeneous lung growth following extensive lung resection by high-resolution computed tomography. J Appl Physiol. 107 (5), 1569-1578 (2009).

- Voswinckel, R., et al. Characterisation of post-pneumonectomy lung growth in adult mice. Eur Respir J. 24 (4), 524-532 (2004).

- Ravikumar, P., et al. Regional Lung Growth and Repair Regional lung growth following pneumonectomy assessed by computed tomography. J Appl Physiol. 97, 1567-1574 (2004).

- Gibney, B. C., et al. Detection of murine post-pneumonectomy lung regeneration by 18FDG PET imaging. EJNMMI Res. 2 (1), (2012).

- Muñoz-Barrutia, A., Ceresa, M., Artaechevarria, X., Montuenga, L. M., Ortiz-De-Solorzano, C. Quantification of lung damage in an elastase-induced mouse model of emphysema. Int J Biomed Imaging. 2012, (2012).

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved