A subscription to JoVE is required to view this content. Sign in or start your free trial.

Method Article

Validation of a Psychosocial Intervention on Body Image in Older People: An Experimental Design

In This Article

Summary

This experimental intervention examines the body satisfaction of older people. The aim is to compare a specific intervention with another general program and determine which is more effective for improving body satisfaction in people over fifty years old.

Abstract

For most people, body satisfaction is crucial to develop both a positive self-concept and self-esteem, and therefore, it can influence mental health and well-being. This idea has been tested with younger people, but no studies explore whether body image interventions are useful when people age. This research validates a specific program designed for older people (IMAGINA Specific Body Image Program). This is done by employing a mixed experimental design, with between-subject and within-subject comparisons that focus on body satisfaction before and after experimental treatment, comparing two groups. Using this experimental methodology makes it possible to identify the effect of the intervention in a group of 176 people. The score obtained with the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) was the dependent variable, and the IMAGINA program was the independent one. As for age, gender, relationship status, season, and residence environment, these were controlled variables. There were significant differences in body satisfaction between the two programs, obtaining better results with IMAGINA. The controlled variables had a much less significant effect than the treatment. Therefore, it is possible to improve body satisfaction in older adults through interventions similar to the one presented here.

Introduction

In Western societies, looking good, healthy, and young is very important to feel right, fit in, interact with others, and be successful, becoming a core element of the self-concept and self-esteem. How satisfied one person is with her/his body depends on personal perception, specifically, with how s/he feels, perceives, imagines, and reacts to physical appearance and body functioning1,2. Following this definition, it is possible to identify two qualitatively different dimensions within this construct. On the one hand, there is the perceptive dimension, which depends on evaluating the size, shape, and proportions of the body itself; on the other hand, there is the cognitive-emotional domain (i.e., 'body satisfaction'3), which is the subject of this research.

Essentially, body satisfaction is a person's degree of acceptance of his or her physical appearance4, which is bad if this assessment affects self-confidence negatively and positive when it increases personal confidence in interacting with others5,6. Traditionally, it has been considered that when a person ages and enters the last stage of life (taking age 50 as the cut-off point for middle age), body image concerns decrease substantially. In other words, it is believed that perceptual distortions about body image typical in adolescence and youth6,7,8 are rare in older people9,10. The reason is that the focus of concern shifts from weight and fitness to other significant physical defects more associated with lack of health and physical decline.

In this line, the scientific literature has shown that the main concerns about the physical appearance of older people focus on the signs of aging, such as loss of fitness, wrinkling and aging skin, hair loss and grey hair, body odor, among others11,12. It has also been argued that the perception of these aging signs plays an evolutionary and adaptive role, since it allows people to become progressively aware of aging, thus helping to accept the transformation and deterioration of physical appearance. Although this may be right, it is no less true that aging awareness negatively influences body satisfaction. Not in vain, the widespread phenomenon of 'midlife crisis' refers to a tipping point in which the person starts to realize that s/he is aging and, in some cases, this comes along with experiencing depressive symptoms which, if not properly addressed, can interfere with personal wellbeing and mental health11,13.

The psychological and emotional implications derived from the senescence awareness have been studied14. In that sense, the deterioration of the physical appearance has been considered the most unmistakable sign that someone can experience regarding the arrival of senescence15. This is coupled with the feeling of playing an irrelevant and undervalued social role 16. Therefore, self-identification as an 'older person' is irremediably linked to a gradual acceptance of new limitations and unfavorable circumstances. Thus, the older person begins to experience difficulties and emotional problems, such as anxiety, stress, or depression. Shortly, the person may self-identify with negative social roles while poorly accepting the physical limitations associated with aging17,18.

In different age groups, such as adolescents and youth, it is known that satisfaction and body image can improve with intervention programs1,19. Examples of this are the well-known interventions of Cash (1997)20 and PICTA (Preventive program on body image and eating disorders in Spanish) by Maganto, del Río and Roiz (2002)21, as well as some more recent programs (Kilpela et al., 2016)22, Halliwell et al. (2016)23, McCabe et al. (2017)24 or Bailey, Gammage and Van Ingen (2019)25. However, none of them target mature people and focus mainly on females, except for the intervention developed by Sánchez-Cabrero (2012)26 called 'IMAGINA' that this study aims to validate. Let us suppose that a therapeutic intervention on body image can contribute to self-acceptance and develop a positive self in young people. There is no reason for not applying it and intervening in older people who face radical changes in their bodies27,28,29.

The experimental design is the most effective methodology for determining causal relationships and evaluating whether a therapeutic intervention produces improvements. First, it is necessary to isolate the intervention effect from the rest of the intervening variables, something that in the social sciences is very costly and complex since the factors that can influence are almost innumerable. Second, it also requires a pre-post treatment comparison, comparisons between control and experimental groups, the randomization of the participants in the conditions of control and treatment, as well as the study of the most relevant intervening variables. Thus, this experiment follows two main objectives: (1) to analyze the improvement in body image satisfaction of persons over 50 years of age enrolling in a specific program of body satisfaction compared with the progress gained in a general program (non-specific); (2) to examine the relationship between body satisfaction and intervening variables such as age, gender, relationship status, time of year of participation, and living either in a metropolitan or countryside residence.

Protocol

The Committee reviewed the Protocol on Scientific Conduct and Ethics of the Alfonso X el Sabio University. Also, a group of scientists external to the research team checked and approved the complete experimental process. To allowing participation in the study, it was necessary to sign an informed consent accepting to enroll in the program, as recommended by the Declaration of Helsinki30. Before enrollment, it was ensured that none of the participants would suffer any psychological stress or harm resulting from the intervention.

1. Carry out the field study

NOTE: The experimental design follows a mixed design, with between-subject measurements (experimental and control groups) and repeated measurements before and after treatment. This experimental design makes it possible to isolate the effect of treatment (the results obtained in a specific body satisfaction program) from other variables related to the individual differences since body satisfaction was measured before and after treatment. The study also compares the treatment with what happened when participating in a non-specific intervention program (control group) isolating the manipulation effect during the intervention. Participants were randomly allocated in the experimental and control conditions, guarantying the optimal conditions for the experiment to be conducted.

- Selection of research tools

- Choose a psychosocial program aimed at improving body image in older people adequate to the goal of the study. In this case, the option chosen was IMAGINA program by Sánchez-Cabrero (2012)26 as it meets all the requirements.

NOTE: The criterion to select the experimental instrument were the following: (1) it had to be a program specifically for body satisfaction; (2) it must be perfectly adapted to older people; (3) it must be a group-program emphasizing social interaction between participants; (4) it has to last 6 to 10 session of 60-120 minutes each, so attitudinal and behavioral changes could be achieved consistently. - Choose a general psychosocial program for older people to work in groups that meet all the required conditions and serve as a control comparison. In this experiment, the program is 'Promoting Healthy Aging: Consistent Health', run by the Spanish Red Cross31 since it was the best option available.

NOTE: The criterion to select the control program are that (1) it must build upon positive social interaction without focusing on body image; (2) it must be designed for working in groups; (3) it must be appropriate for older people; (4) it must have a schedule similar to the experimental intervention program. - Choose a scientific instrument to evaluate body image satisfaction in older people. The Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) by Cooper, Taylor, Cooper, and Fairburn (1987)33 was regarded as the most suitable instrument for the research goals.

NOTE: The criterion to select the scientific instrument to evaluate body satisfaction in old age were that (1) it must be a peer-reviewed and published instrument; (2) it measures body satisfaction and has convergent validity with other scientific instruments; (3) it must be short and simple to adapt to the older population (3) it must be translated to Spanish and scaled for the Spanish population. - Design a questionnaire (Supplementary File 1) to gather all demographic data and intervening variables to control in this study.

NOTE: The sociodemographic data regarding age, gender, and relationship status was gathered with an ad hoc specific questionnaire. Age was treated as a quantitative and discrete variable and the rest as dichotomous categorical variables. As for 'season of the year' and 'residence environment', this information was registered by the researcher in charge of the experiment.

- Choose a psychosocial program aimed at improving body image in older people adequate to the goal of the study. In this case, the option chosen was IMAGINA program by Sánchez-Cabrero (2012)26 as it meets all the requirements.

- Sampling method

- Request the collaboration of a non-profit organization (NGO) that carries out psychosocial programs of group-application for older people in different locations.

- Select ten different locations to apply the experimental and control psychosocial programs. Half of them lived in the countryside (places with less than 1000 residents), and the other half lived in metropolitan towns and cities.

- Application of experimental and control interventions

- Perform the pre-treatment measurement of BSQ. Individual measures were gathered with paper and pen, but the participants were in the same space as their cluster group.

- Do over eight sessions of both psychosocial programs (control and experimental) in ten locations.

NOTE: The programs were under the same person's supervision at two different seasons of the year: summer and winter. In both cases, the activities were done in the evening, for 4 weeks, and twice a week. In both programs, participants worked in groups, having playful activities and social gatherings, which drastically reduced participants' withdrawal. - Gather the post-treatment measurement of the BSQ.

NOTE: Individual applications were gathered with paper and pen, but the participants were in the same room with their cluster group. This was made right after finishing the sessions. The BSQ was not applied to those individuals who did not come to all sessions. Consequently, results from 10% of the sample were omitted in the final analyses.

2. Digitize the data obtained in the field study

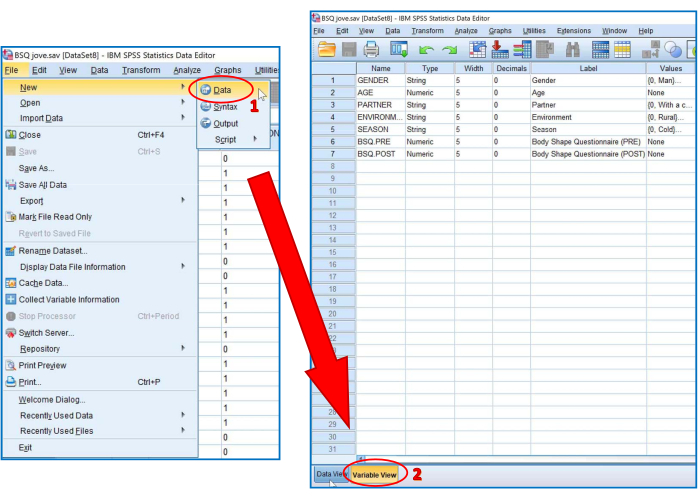

- Open the statistical software and go to File Menu | New | Data, click on the Data icon and then go to Variable View (Figure 1) and create a statistical variable for each one of the following variables shown in Table 1.

| Variable Name | Type | Values | Measure | Description |

| BSQ Pre-treatment measurement | Numerical | 34-204 | Scale | Numerical result obtained in the pre-treatment |

| BSQ Post-treatment | Numerical | 34-204 | Scale | Numerical result obtained in the measurement post-treatment |

| Experimental Condition | Dichotomous variable | {0, CONTROL} / {1, EXPERIMENTAL} | Nominal | Whether or not the participant has been in the experimental or control condition |

| Gender | Dichotomous variable | {0, Man} / {1, Woman} | Nominal | The biological gender of the participant |

| Age | Numerical | 50-85 | Scale | The age of the participants measured in years |

| Stable Relationship Status | Dichotomous variable | {0, With a current partner} / {1, Without a current partner} | Nominal | Whether or not the participant is in a formal relationship |

| Environment of Residence | Dichotomous variable | {0, Rural} / {1, Urban} | Nominal | Whether or not the participant lives in countryside (locality of fewer than 1000 inhabitants) or metropolitan (locality of more than 1000 inhabitants) |

| Season of intervention | Dichotomous variable | {0, Cold} / {1, Warm} | Nominal | Whether or not the treatment took place in winter or summer |

Table 1: Main characteristics of the research statistical variables. Detailed description of the main characteristics of the research variables in their digitization process.

Figure 1: How to import variables data to the statistical software package. (1) Click on the Data icon; (2) Click on Variable View icon. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

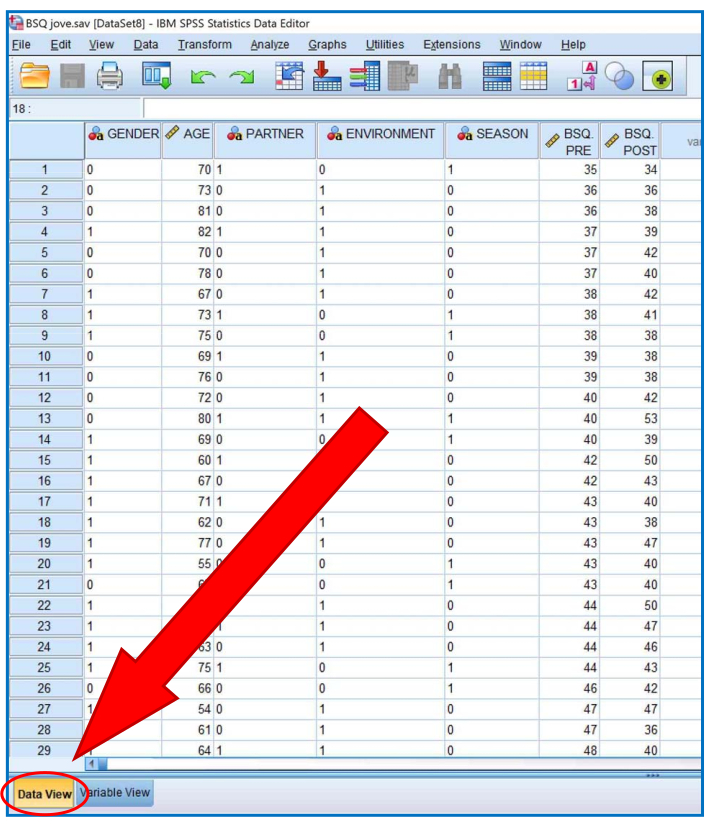

- Go to Data View in the statistical software (Figure 2), and, for each participant, fill in the data of the pre- and post-measures of the BSQ test. Do the same with the demographic and attributive data of the questionnaire.

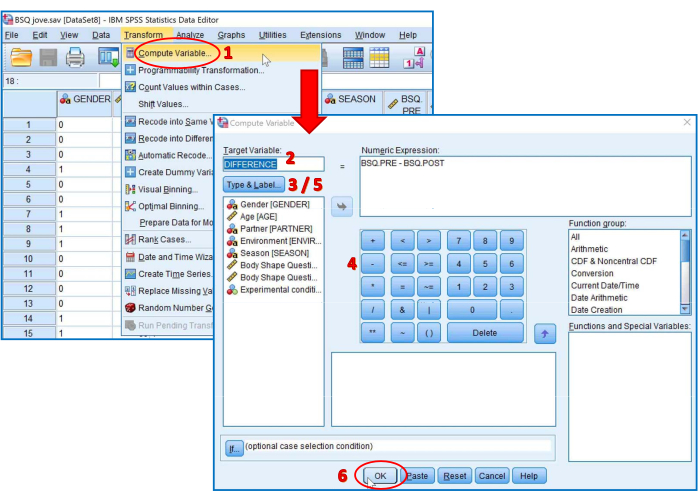

NOTE: The results obtained with the BSQ and the information regarding the study's socio-demographic data were collected in paper and pen, so it was necessary to digitalize it one by one.- Create a new variable with the difference between the pre- and post- BSQ measurement in the statistical software (data obtained with the test). To do so, go to Transform | Compute Variable, and in the pop-up menu assign a name in Target Variable gap, then select the pre-treatment variable from the menu Type & Label… and move it to Numeric Expression gap, then click on the subtraction icon (-) on the calculator.

- After, select the post-treatment variable from the Type & Label menu and move it again to Numeric Expression gap. Finally, click on the OK, and then the variable that accounts for the difference between pre- and post-measurement is created (Figure 3).

Figure 2: How to import research data to the statistical software package. Select Data View icon. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 3: How to create a new variable with the difference between the pre- and post-measurement of the BSQ test in the statistical software. (1) Click on Transform | Compute Variable; (2) Assign a number in Target Variable gap; (3) Select the pre-treatment variable from the menu Type & Label… and move it to Numeric Expression gap; (4) Click on the Subtraction icon (-) on the calculator; (5) Select the post-treatment variable from the Type & Label menu and move it to Numeric Expression gap; (6) click on the OK icon. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

3. Statistical analyses

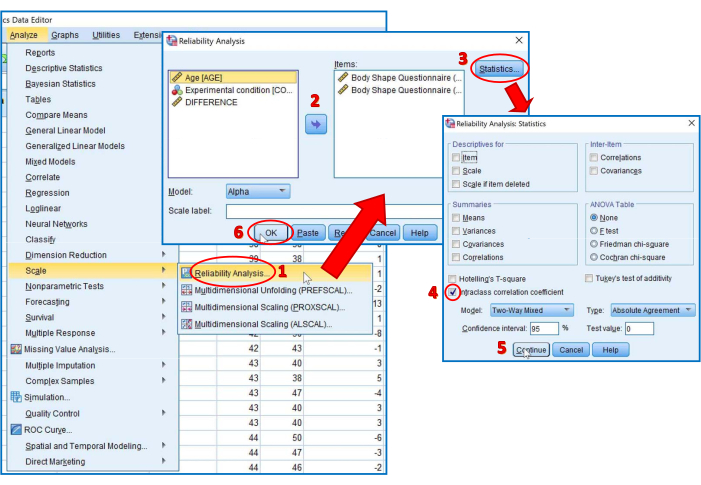

- Look at the reliability and consistency of BSQ measurement and retest with the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC) with the statistical software package.

- To this end, select the Analyze Menu | Scale | Reliability Analysis, move the pre and post-treatment BSQ measurements used in the experiment to the Reliability Analysis dialogue box.

- Click on Statistics… and choose Intraclass Correlation Coefficient and the options Two-Way Mixed and Consistency. Finally, click on the OK icon to generate the desired output (Figure 4).

Figure 4: How to assess the internal consistency of the questionnaire. Select Analyze Menu | Scale | Reliability Analysis. (1) Move the variables used in the experiment to the Reliability Analysis dialogue box; (2) Click on the OK icon. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

NOTE: The pre and post-treatment BSQ measurements had excellent reliability and consistency values (ICC=0.916).

- Run the descriptive analysis with the statistical software package. Start with descriptive statistics such as the arithmetic mean and the standard deviation (SD) for the quantitative variables 'BSQ pre-treatment', 'BSQ post-treatment', and 'Pre-post difference'. First globally, then taking into account each category of the other variables included in the study. Finally, study the frequency distribution in the categorical intervening and controlled variables.

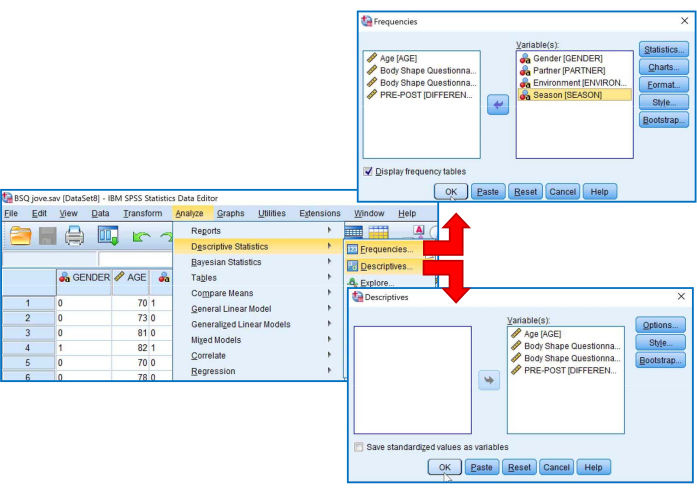

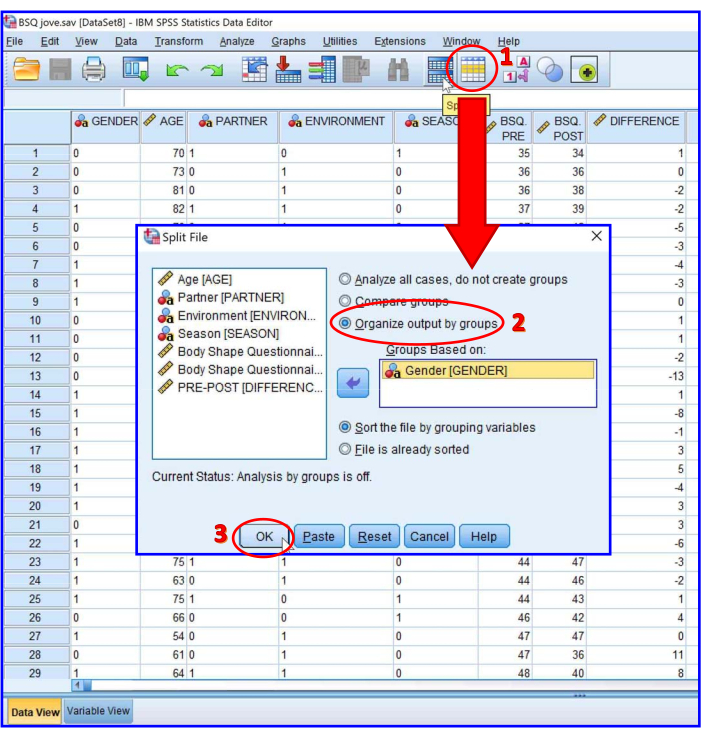

- To do this analysis, select Analyze Menu | Descriptive Statistics | Frequencies and, after the output, analyze | Descriptive Statistics | Descriptive (Figure 5). To specify the descriptive statistics of the quantitative variables for each condition of the categorical variables, select the option Split File in the main menu, and in the pop-up menu choose the categorical variable to be analyzed and select the option 'Organize output by groups'; then click on OK (Figure 6).

- Repeat this process for each categorical variable considered in the study (experimental condition, time of year, gender, marital status and residence).

Figure 5: How to carry out the descriptive analysis of the data. Select Analyze Menu | Descriptive Statistics | Frequencies and, after the output, Analyze | Descriptive Statistics | Descriptive. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 6: How to specify the descriptive statistics of the quantitative variables for each condition of the controlled nominal intervening variables. (1) Click on Split File icon; (2) Choose the categorical variable to be analyzed and select the option Organize output by groups; (3) Click on the OK icon. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

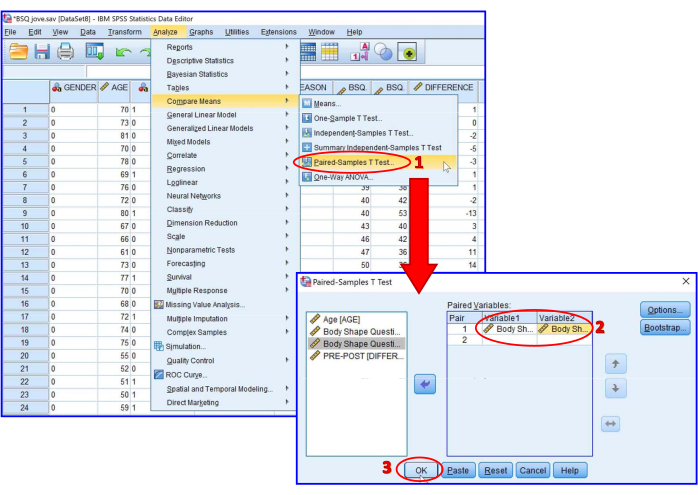

- Conduct a paired samples Student's t-test with the statistical software package to examine body image before and after participating in the two conditions (between-subject IV effect).

- To this end, select Analyze Menu | Compare Means | Paired samples t-Test, and in the Paired samples t-test dialogue box, put BSQ pre-treatment and BSQ post-treatment as Variable 1 and 2 (Figure 7).

- To specify the paired samples Student's t-test according to each categorical variable (experimental condition, gender, marital status, time of year and place of residence) select Split File option in the main menu, and in the pop-up menu choose the categorical variable to be analyzed and select the option 'Organize output by groups' and click on OK (Figure 6).

- Repeat this process before each analysis for each nominal variable (time of year, gender, marital status and residence).

Figure 7: How to conduct Paired samples Student t-Test analysis. (1) Select Analyze Menu | Compare Means | Paired samples t-Test; (2) put BSQ pre-treatment and BSQ post-treatment as Variable 1 and 2; (3) Click on the OK icon. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

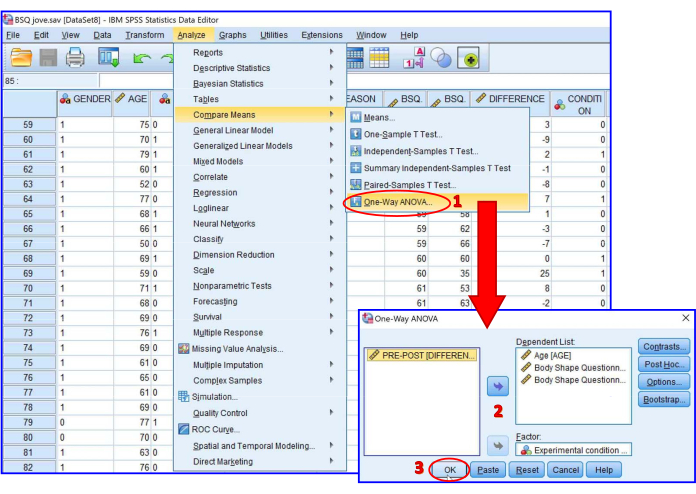

- Conduct One-Way ANOVA analysis with the statistical software package to see the effect of each program (intergroup IV effect), gender, relationship status, time of year, and place of residence.

- To this end, select Analyze Menu | Compare Means | One-Way ANOVA (Figure 8), and in the One-Way ANOVA dialogue box, put the variables BSQ pre-treatment, BSQ post-treatment and the pre-post difference in the Dependent List and the experimental condition variable as the Factor.

- Repeat this process for each of the nominal variables (experimental condition, gender, relationship status, time of year and place of residence). The output shows the statistical significance of the BSQ pre-treatment, BSQ post-treatment and the pre-post difference as a discrete quantitative variable by comparing means with the Snedecor's F distribution (non-considering equality of variances).

Figure 8: How to conduct One-Way ANOVA analysis. (1) Select Analyze Menu | Compare Means | One-Way ANOVA; (2) put the variables BSQ pre-treatment, BSQ post-treatment and the pre-post difference in the Dependent List, and the experimental condition variable as the Factor; (3) Click on the OK icon. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

- Conduct Repeated Measures ANOVA analysis with the statistical software package using the Pillai's Trace and Wilks' Lambda statistics, as they offer opposite and complementary results of the inter-intragroup effect of independent variables.

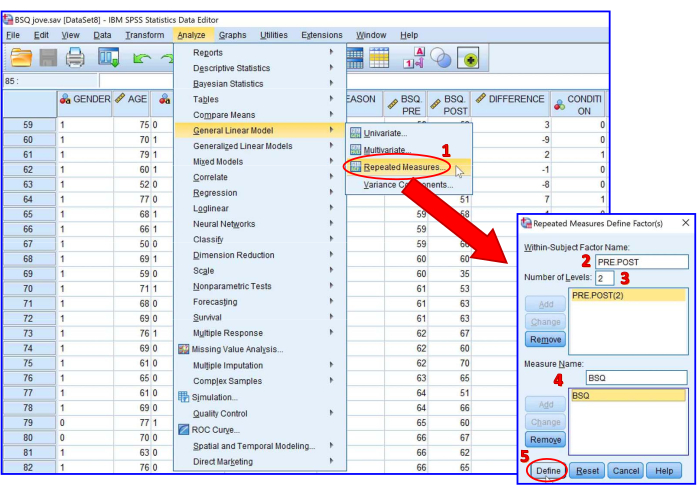

- To this end, select Analyze Menu | General Linear Model | Repeated Measures, and in the Repeated Measures dialogue box, assign a name in the Within-Subject Factor Name box (e.g., PRE-POST), put '2' in the Number of Levels box and in the Measure Name box put BSQ. Finally, click on 'Define' icon to switch to the variable selection box (Figure 9).

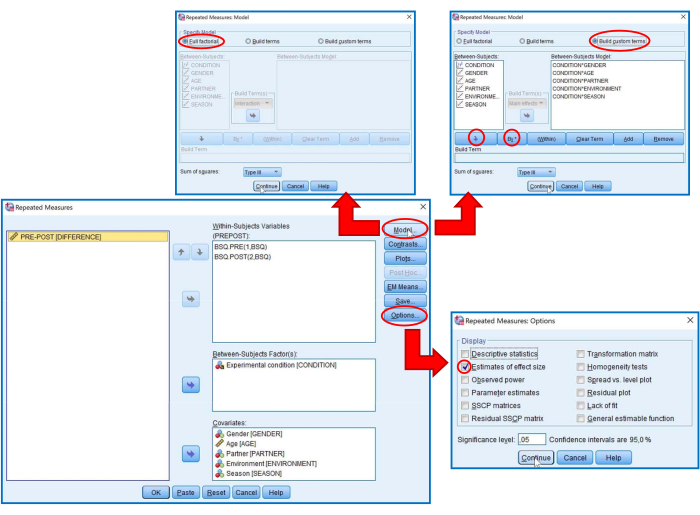

- Within that pop-up menu, select the pre- and post-measures of the test BSQ as Within-Subjects Variables, the experimental condition as Between-Subjects Factor (s), and all the sociodemographic variables (time of year, gender, age, marital status and residence environment) as Covariates.

- Before obtaining the analysis result, click on Model and select 'Full factorial'; then go to 'Options' and choose 'Estimates of effect size' (see Figure 10). Finally, repeat the whole process but instead of choosing 'Full factorial' in Model choose the option 'Build custom terms', combining the variable 'Condition' with all the sociodemographic variables (time of year, gender, age, marital status and residence environment) using for this purpose the icon 'By *'.

Figure 9: How to configure Repeated Measures ANOVA analysis. (1) Select Analyze Menu | General Linear Model | Repeated Measures; (2) Assign a name in the Within-Subject Factor Name box; (3) Put '2' in the Number of Levels box and click on Add icon; (4) Put BSQ in the Measure Name box and click on Add icon; (5) Click on the Define icon. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Figure 10: How to select variables to conduct Repeated Measures ANOVA analysis. Select the pre- and post-measures of the test BSQ as Within-Subjects Variables and the experimental condition as Between-Subjects Factor (s). Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Results

The experimental research followed a mixed design, with between-subject measurements (experimental and control groups) and repeated measurements before and after treatment.

IMAGINA program by Sánchez-Cabrero (2012)26 was selected as the experimental therapeutical program to increase body image satisfaction of older adults in Spain. It has eight group-sessions of 90-120 minutes duration each, aiming at entertaining and engaging participants, using activities pr...

Discussion

This experimental work supports the positive consequences of participating in a body satisfaction program in older people by examining satisfaction values before and after the intervention and comparing experimental and non-experimental groups. Also, the control of other intervening variables improves the reliability and validity of the results obtained.

The most critical step of the protocol was the selection of the program applied in the control group. It was necessary to replicate the same ...

Disclosures

The authors have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgements

All contributing authors wish to express their gratitude to the Spanish Red Cross, because without its support we could not have done this research. Also, we appreciate a lot of the feedback and help from the Committee on Scientific Conduct and Ethics of the Alfonso X el Sabio University.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) | International Journal of Eating Disorders | 1987 | Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) developed by Cooper, Taylor, Cooper, and Fairburn (1987), which was adapted and scaled to Spanish participants by Raich et al. (1996). This is a self-report of 34 items following a Likert scale that goes from 1 (never) to 6 (always). The final score ranges from 34 to 204 and scoring above 110 indicates dissatisfaction and discomfort with physical appearance (Cooper et al., 1987). It is a reliable instrument since several studies have reported Cronbach’s α between 0.95 and 0.97. Also, the BSQ has good external validity, i.e., it is convergent with other similar tools, such as the Multidimensional Body Self-Relations Questionnaire, MBSRQ (Cash, 2015) and the body dissatisfaction subscale of the Eating Disorders Inventory, EDI (Garner, Olmstead, and Polivy, 1983). |

| IMAGINA: programa de mejora de la autoestima y la imagen corporal para adultos | Sinindice | 2012 | IMAGINA Program was meant to be a therapeutical tool to increase a body image satisfaction of older adults in Spain. It has eight group-sessions of 90-120 minutes duration each, aiming at entertaining and engaging participants. Body image and self-esteem are expected to improve through social participation, communication, body image workshops, and healthy nutrition information. |

| Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) | IBM | 24 | Software package used in statistical analysis of data |

References

- Cash, T. F. Body Image: A joyous journey. Body Image. 23, 1-2 (2017).

- Sánchez-Cabrero, R., León-Mejía, A. C., Arigita-García, A., Maganto-Mateo, C. Improvement of Body Satisfaction in Older People: An Experimental Study. Frontiers inPsychology. 10 (2823), (2019).

- Maganto, C., Garaigordobil, M., Kortabarria, L. Eating Problems in Adolescents and Youths: Explanatory Variables. The Spanish Journal of Psychology. 19, 81 (2016).

- McGuire, J. K., Doty, J. L., Catalpa, J. M., Ola, C. Body image in transgender young people: Findings from a qualitative, community based study. Body Image. 18, 96-107 (2016).

- Tylka, T. L., Wood-Barcalow, N. L. What is and what is not positive body image? Conceptual foundations and construct definition. Body Image. 14, 118-129 (2015).

- Fernández-Bustos, J. -. G., González-Martí, I., Contreras, O., Cuevas, R. Relación entre imagen corporal y autoconcepto físico en mujeres adolescentes. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología. 47 (1), 25-33 (2015).

- Grogan, S. . Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women and children. , (2016).

- Kvalem, I. L., Træen, B., Markovic, A., von Soest, T. Body image development and sexual satisfaction: A prospective study from adolescence to adulthood. The Journal of Sex Research. 56 (6), 791-801 (2019).

- Jankowski, G. S., Diedrichs, P. C., Williamson, H., Christopher, G., Harcourt, D. Looking age-appropriate while growing old gracefully: A qualitative study of ageing and body image among older adults. Journal of Health Psychology. 21 (4), 550-561 (2016).

- Sabik, N., Versey, H. S. Functional limitations, body perceptions, and health outcomes among older African American women. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 22 (4), 94 (2016).

- Gubrium, J. F., Holstein, J. A. The Life Course. Handbook of symbolic interactionism. , 835-855 (2006).

- Longo, M. R. Implicit and explicit body representations. European Psychologist. 10 (1), 6-15 (2015).

- Chang, H. K. Influencing factors on mid-life crisis. Korean Journal of Adult Nursing. 30 (1), 98-105 (2018).

- Sánchez-Cabrero, R., Carranza-Herrezuelo, N., Novillo-López, M. A., Pericacho-Gómez, F. J. The Importance of Physical Appearance during the Ageing Process in Spain. Interrelation between Body and Life Satisfaction during Maturity and the Old Age. Activities, Adaptation & Aging. 44 (3), 210-224 (2020).

- Schoufour, J. D., et al. Socio-economic indicators and diet quality in an older population. Maturitas. 107, 71-77 (2018).

- Kihlstrom, J. F., Srull, T. K., Wyer, R. S. . What does the self-look like? The mental representation of trait and autobiographical knowledge about the self. , 87-98 (2015).

- Bratt, C., Abrams, D., Swift, H. J., Vauclair, C. M., Marques, S. Perceived age discrimination across age in Europe: From an ageing society to a society for all ages. Developmental Psychology. 54 (1), 167-180 (2018).

- Sanchez-Cabrero, R. Mejora de la satisfacción corporal en la madurez a través de un programa específico de imagen corporal. Universitas Psychologica. 19 (1), 1-15 (2020).

- Voelker, D. K., Reel, J. J., Greenleaf, C. Weight status and body image perceptions in adolescents: Current perspectives. Adolescent Health, Medicine and Therapeutics. 6, 149-158 (2015).

- Cash, T. F. . The body image workbook: An 8-step program for learning to like your looks. , (1997).

- Maganto, C., Del Río, A., Roiz, O. . Programa preventivo sobre Imagen corporal y Trastornos de la Alimentación (PICTA). , (2002).

- Kilpela, L. S., Blomquist, K., Verzijl, C., Wilfred, S., Beyl, R., Becker, C. B. The body project 4 all: A pilot randomized controlled trial of a mixed-gender dissonance-based body image program. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 49 (6), 591-602 (2016).

- Halliwell, E., et al. Body image in primary schools: A pilot evaluation of a primary school intervention program designed by teachers to improve children's body satisfaction. Body Image. 19, 133-141 (2016).

- McCabe, M. P., Connaughton, C., Tatangelo, G., Mellor, D., Busija, L. Healthy me: A gender-specific program to address body image concerns and risk factors among preadolescents. Body Image. 20, 20-30 (2017).

- Bailey, K. A., Gammage, K. L., van Ingen, C. Designing and implementing a positive body image program: Unchartered territory with a diverse team of participants. Action Research. 17 (2), 146-161 (2019).

- Sánchez-Cabrero, R. . IMAGINA: programa de mejora de la autoestima y la imagen corporal para adultos. , (2012).

- Kozar, J. M. Relationship of attitudes toward advertising images and self-perceptions of older women. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. 65 (8), 3116 (2005).

- Hudson, N. W., Lucas, R. E., Donnellan, M. B. Getting older, feeling less? A cross-sectional and longitudinal investigation of developmental patterns in experiential well-being. Psychology and Aging. 31 (8), 847-861 (2016).

- Mangweth-Matzek, B., et al. Never too old for eating disorders or body dissatisfaction: A community study of elderly women. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 39 (7), 583-586 (2006).

- World Medical Association. WMA declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. World Medical Association. , (2013).

- Spanish Red Cross. . Promoting Healthy Aging: Consistent Health. , (2017).

- Spanish Red Cross. . Exercise book and mental agility activities for the elderly. , (2013).

- Cooper, P. J., Taylor, M. J., Cooper, Z., Fairburn, C. G. The development and validation of the Body Shape Questionnaire. International Journal of Eating Disorders. , (1987).

- Raich, R. M., et al. Adaptación de un instrumento de evaluación de la insatisfacción corporal (BSQ). Clínica y Salud. 8, 51-66 (1996).

- Garner, D. M., Olmstead, M. P., Polivy, J. Development and validation of a multidimensional eating disorder inventory for anorexia nervosa and bulimia. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2 (2), 15-34 (1983).

- Cash, T. F. Multidimensional Body-Self Relations Questionnaire (MBSRQ). Encyclopedia of Feeding and Eating Disorders. , 1-4 (2015).

- Baile, J. I., Guillén, F., Garrido, E. Insatisfacción corporal en adolescentes medida con el Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ): Efecto del anonimato, el sexo y la edad. Revista Internacional de Psicología Clínica y de La Salud. 2 (3), 439-450 (2002).

- Conti, M. A., Cordás, T. A., Latorre, M. R. D. O. A study of the validity and reliability of the Brazilian version of the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ) among adolescents. Revista Brasileira de Saúde Materno Infantil. 9 (3), 331-338 (2009).

- Moreno, D. C., Montaño, I. L., Prieto, G. A., Pérez-Acosta, A. M. Validación del Body Shape Questionnaire (Cuestionario de la Figura Corporal) BSQ para la población colombiana. Acta Colombiana de Psicología. 10 (1), 15-23 (2015).

- Kapstad, H., Nelson, M., Øverås, M., Rø, &. #. 2. 1. 6. ;. Validation of the Norwegian short version of the Body Shape Questionnaire (BSQ-14). Nordic Journal of Psychiatry. 69 (7), 509-514 (2015).

- Kim, T. S., Chee, I. S. The reliability and validity of the Korean version of the Body Shape Questionnaire. Anxiety Mood. 14 (1), 36 (2018).

- Homan, K. J., Tylka, T. L. Development and exploration of the gratitude model of body appreciation in women. Body Image. 25, 14-22 (2018).

- Tylka, T. L., Homan, K. J. Exercise motives and positive body image in physically active college women and men: Exploring an expanded acceptance model of intuitive eating. BodyImage. 15, 90-97 (2015).

- Mellor, D., Connaughton, C., McCabe, M. P., Tatangelo, G. Better with age: A health promotion program for men at midlife. Psychology of Men and Masculinity. 18 (1), 40-49 (2017).

- Roses-Gómez, M. R. Desarrollo y evaluación de la eficacia de dos programas preventivos en comportamientos no saludables respecto al peso y la alimentación: Estudio piloto. Universidad Autónoma de Barcelona. , (2014).

- Fardouly, J., Diedrichs, P. C., Vartanian, L. R., Halliwell, E. The Mediating Role of Appearance Comparisons in the Relationship Between Media Usage and Self-Objectification in Young Women. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 39 (4), 447-457 (2015).

- Ridgway, J. L., Clayton, R. B. Instagram unfiltered: Exploring associations of body image satisfaction, Instagram# selfie posting, and negative romantic relationship outcomes. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking. 19 (1), 2-7 (2016).

- Raich, R. M. Una perspectiva desde la psicología de la salud de la imagen corporal. Avances En Psicología Latinoamericana. 22 (1), 15-27 (2004).

- Thompson, J. K. . Handbook of eating disorders and obesity. , (2004).

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionExplore More Articles

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved