需要订阅 JoVE 才能查看此. 登录或开始免费试用。

Method Article

磷脂介质诱导的三维培养物转化

摘要

本协议描述了未转化的乳腺上皮细胞系MCF10A的3D “顶部”培养物的建立,该培养物已被修改以研究血小板活化因子(PAF)诱导的转化。免疫荧光已被用于评估转化,并详细讨论。

摘要

已经开发了几种模型来研究癌症,例如啮齿动物模型和已建立的细胞系。使用这些模型的研究提供了对致癌作用的宝贵见解。细胞系提供了与乳腺肿瘤发生相关的分子信号传导失调的理解,而啮齿动物模型广泛用于研究体内乳腺癌的细胞和分子特征。 乳腺上皮细胞和癌细胞的3D培养物的建立有助于通过模拟体内体外条件来弥合体内和体外模型之间的差距。该模型可用于了解复杂分子信号传导事件的失调和乳腺癌变过程中的细胞特征。在这里,修改了3D培养系统以研究磷脂介质诱导的(血小板活化因子,PAF)转化。免疫调节剂和其他分泌分子在乳房肿瘤的发生和进展中起主要作用。在本研究中,暴露于乳腺上皮细胞的3D腺泡培养物暴露于PAF表现出转化特征,例如极性丧失和细胞特征改变。该3D培养系统将有助于揭示由肿瘤微环境中各种小分子实体诱导的遗传和/或表观遗传扰动。此外,该系统还将为鉴定可能参与转化过程的新型和已知基因提供一个平台。

引言

有无数的模型可用于研究癌症的进展,每个模型都是独一无二的,代表了这种复杂疾病的一种亚型。每个模型都为癌症生物学提供了独特而有价值的见解,并改进了模拟实际疾病状况的方法。作为单层生长的已建立细胞系为体外重要过程提供了宝贵的见解,例如增殖,侵袭性,迁移和凋亡1。尽管二维(2D)细胞培养一直是研究哺乳动物细胞对几种环境扰动的反应的传统工具,但推断这些发现以预测组织水平的反应似乎不够令人信服。2D培养的主要局限性在于产生的微环境与乳腺组织本身的微环境有很大不同2。2D培养缺乏细胞与细胞外基质的相互作用,这对于任何组织的生长都至关重要。此外,细胞在单层培养物中经历的拉力会阻碍这些细胞的极性,从而改变细胞信号传导和行为3,4,5。三维(3D)培养系统具有模拟体外体内条件的能力,为癌症研究领域开辟了一条新途径。 在2D细胞培养中丢失的许多关键微环境线索可以使用富含层粘连蛋白的细胞外基质(lrECM)的3D培养物重新建立6。

各种研究已经确定了肿瘤微环境在致癌中的重要性7,8。炎症相关因素是微环境的主要部分。血小板活化因子(PAF)是由各种免疫细胞分泌的磷脂介质,介导多种免疫反应9,10。高水平的PAF由不同的乳腺癌细胞系分泌,并与增殖增强有关11。我们实验室的研究表明,腺泡培养物中PAF的长期存在导致乳腺上皮细胞的转化12。PAF激活PAF受体(PAFR),激活PI3K/Akt信号轴13。据报道,PAFR 也与 EMT、侵袭和转移有关14。

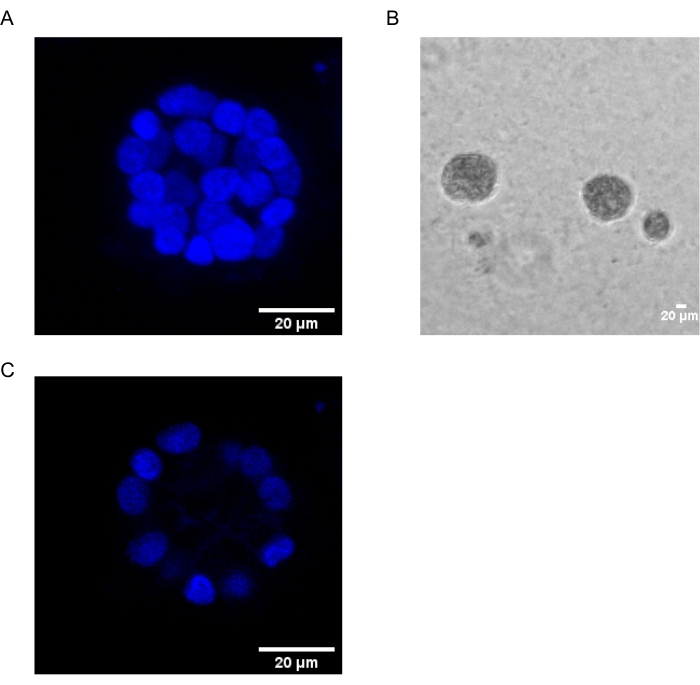

本协议展示了一个模型系统来研究PAF诱导的转化,使用乳腺上皮细胞的3D培养物,如Chakravarty等人之前所描述的那样12。在细胞外基质(3D培养物)上生长的乳腺上皮细胞倾向于形成极化生长停滞球状体。这些被称为腺泡,与乳腺组织的腺泡非常相似,乳腺是乳腺最小的功能单位,在 体内15。 这些球体(图1A,B)由单层紧密堆积的极化上皮细胞组成,围绕空心腔并附着在基底膜上(图1C)。这种形态发生过程已在文献16中得到了很好的描述。当接种在lrECM上时,细胞经历分裂和分化以形成细胞簇,然后从第4天开始极化。到第8天,腺泡由一组与细胞外基质直接接触的极化细胞和封闭在外极化细胞内的一簇非极化细胞组成,与基质没有接触。已知这些未极化的细胞在培养的第12天发生凋亡,形成空心腔。到第16天,形成生长停滞的结构16。

图1:用核染色的腺泡中的细胞核 。 (A)腺泡的3D构造。(B)在基质胶上生长20天的MCF10A腺泡的相衬图像。(C)最中间的部分显示了空心腔的存在。比例尺 = 20 μm。 请点击此处查看此图的大图。

与2D培养不同,腺泡培养有助于通过明显的形态变化区分正常细胞和转化细胞。未转化的乳腺上皮细胞形成具有空腔的腺泡,模仿正常人乳腺腺泡。这些球体在转化时显示出破坏的形态,其特征是极性严重丧失(癌症的标志之一),没有管腔或空腔的破坏(由于细胞凋亡的逃避),这可能是由于各种基因的失调引起的17,18,19,20.这些转化可以使用常用的技术(如免疫荧光)进行研究。因此,3D细胞培养模型可以作为研究乳腺腺泡形态发生和乳腺癌发生的过程的简单方法。建立3D培养系统以了解磷脂介质PAF的作用将有助于高通量临床前药物筛选。

这项工作采用了3D“顶部”培养协议16,21,以研究PAF22诱导的转化。使用免疫荧光研究了腺泡暴露于磷脂介质引起的表型变化。研究中使用了各种极性和上皮到间充质转化(EMT)标记12,16。表1提到了它们的正常定位和转化时的预期表型。

| 抗体 | 标志着 | 正常本地化 | 转化表型 |

| α6-整合素 | 基底外侧 | 基底侧染色较弱 | 强烈的横向/顶端染色 |

| β-连环蛋白 | 细胞-细胞连接 | 基底外侧 | 异常/核或细胞质定位 |

| 维门汀 | EMT | 不存在/弱存在 | 上调 |

表1:研究中使用的标记物。 在存在和不存在PAF治疗的情况下,使用不同的标记物进行定位。

该方法可以最好地用于研究/筛选各种乳腺癌亚型的合理药物和靶基因。这可以提供更接近 体内 情景的药物反应数据,有助于更快、更可靠的药物开发。此外,该系统可用于研究与药物反应和耐药性相关的分子信号传导。

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

研究方案

1. 在 lrECM 中接种 MCF10A 细胞

- 将MCF10A细胞(贴壁性乳腺上皮细胞)维持在生长培养基中。每4天传代一次细胞。

注意:生长培养基的组成:不含丙酮酸钠的高葡萄糖DMEM含马血清(5%),胰岛素(10μg/ mL),氢化可的松(0.5μg/ mL),表皮生长因子EGF(20ng / mL),霍乱毒素(100ng / mL)和青霉素 - 链霉素(100单位/ mL)(见 材料表)。 - 在实验开始前20分钟在冰上解冻lrECM(见 材料表)。接种细胞的那一天通常被认为是第0天。

- 为了胰蛋白酶消化细胞,吸出培养基,并用2mL PBS洗涤。加入 900 μL 0.05% 胰蛋白酶-EDTA,并在 37 °C 下孵育 ~15 分钟或直到细胞完全胰蛋白酶消化。

- 在腔盖玻片的八个孔中准备lrECM床(见 材料表)。

- 当细胞胰蛋白酶消化时,用60μLllrECM包被每个孔,并将其置于37°C CO2 培养箱中最多15分钟。

- 按照以下步骤准备细胞悬液。

- 细胞完全移位后,加入5mL重悬培养基以淬灭胰蛋白酶活性,并在25°C下以112× g 旋转细胞10分钟。

注意:重悬培养基的组成:不含丙酮酸钠的高葡萄糖DMEM,补充马血清(20%)和青霉素 - 链霉素(100单位/ mL)。 - 吸出用过的培养基并将细胞重新悬浮在 2 mL 测定培养基中。充分混合悬浮液以确保形成单细胞悬液。

注意:测定培养基的组成:不含丙酮酸钠的高葡萄糖DMEM,补充马血清(2%),氢化可的松(0.5μg/ mL),霍乱毒素(100ng / mL),胰岛素(10μg/ mL)和青霉素 - 链霉素(100单位/ mL)。 - 使用血细胞计数器计数细胞,并计算在每个孔中接种6 x 103 个细胞所需的细胞悬液体积。

注意:通常最好在计算中包括一个额外的孔,以解决任何移液错误。 - 根据所需的孔数,在覆盖培养基中稀释细胞悬液。

注意:单个孔的覆盖培养基组成如下:400 μL 测定培养基、8 μL lrECM(2% 最终)和 0.02 μL 100 μg/mL EGF(5 ng/mL 最终)。

- 细胞完全移位后,加入5mL重悬培养基以淬灭胰蛋白酶活性,并在25°C下以112× g 旋转细胞10分钟。

- 进行细胞接种。

- 将 400 μL 稀释的细胞悬液加入制备的 lrECM 床(步骤 1.4),小心确保不会干扰 lrECM 床。在37°C下在加湿的5%CO2 培养箱中孵育。

2. PAF处理

- 在细胞接种后3小时加入PAF。在PBS中制备100μM的PAF储备液,并在每个孔中加入所需的0.2μL体积(相当于200nM)。

- 在每次更换培养基期间添加相同浓度的PAF。

3. 用新鲜培养基重新喂食

- 每4天(即第4天,第8天,第12天和第16天)用新鲜培养基补充细胞。

4. 免疫荧光研究以检测长时间暴露于PAF引起的表型变化

- 培养 20 天后,小心地从每个孔中移出培养基,并用 400 μL 预热的 PBS 洗涤孔。

- 通过加入 400 μL 4% 多聚甲醛(通过在 1x PBS 中稀释 16% 多聚甲醛新鲜制备)并在室温下孵育 20 分钟来固定腺泡结构。

- 用冰冷的PBS冲洗孔一次,并在4°C下用含有0.5%Triton X-100的PBS透化10分钟。

- 10分钟后,立即但小心地移出Triton-X 100溶液,并用400μLPBS-甘氨酸冲洗(通过在1x PBS中加入一小撮甘氨酸新鲜制备)。重复三次,每次15分钟。

- 在免疫荧光(IF)缓冲液中加入400μL含有10%山羊血清(参见 材料表)的初级封闭溶液,并在室温下孵育60分钟。

注意:IF缓冲液的组成:0.05%叠氮化钠,0.1%BSA,0.2%Triton-X 100和0.05%吐温(20合1 PBS)。 - 除去一级封闭溶液,加入在一级封闭溶液中制备的200μL2%二级封闭抗体(山羊中培养的抗小鼠抗原的抗体的F(ab')2片段,参见 材料表),并在室温下放置45-60分钟。

- 在2%二级封闭抗体溶液中以1:100稀释度制备一抗(参见 材料表)。除去二级封闭溶液后,加入新鲜制备的抗体并在4°C下孵育过夜。

- 上一步可能引起基底膜液化。在继续实验之前,请等到载玻片达到室温。小心移液一抗溶液,并用 400 μL IF 缓冲液洗涤三次。

- 在最后一次用IF缓冲液洗涤期间,在一级封闭溶液中制备1:200稀释的荧光团偶联二抗(参见 材料表)。将载玻片在二抗溶液中在室温下孵育40-60分钟。

- 用 400 μL IF 缓冲液冲洗载玻片 20 分钟,然后用 PBS 洗涤两次,每次 10 分钟。

- 在室温下用含有0.5ng / mL核染色剂(参见 材料表)的PBS对细胞核进行复染5-6分钟。用 400 μL PBS 清洗载玻片三次,以去除多余的污渍。

- 小心地移出整个PBS,并确保去除残留的溶液。向每个孔中加入一滴封片剂(参见 材料表),使其在室温下静置过夜。

- 将载玻片存放在室温下,并尽快对载玻片进行成像。

- 在共聚焦显微镜上以40倍或63倍放大倍率拍摄图像(参见 材料表),取0.6毫米步长(NA = 1.4)的光学Z切片。

- 使用图像处理软件打开采集的图像(参见 材料表)。使用 3D 投影展示形态差异。

注意:最中间的光学Z截面最适合用于显示极性标记定位的差异。这些可以手动量化,以表示显示特定染色模式的微球的百分比。 - 为了说明蛋白质表达的差异,请进行半定量分析,测量平均灰度值或计算校正后的总细胞荧光(CTCF)23。将数据表示为小提琴图或点图。

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

结果

MCF10A细胞在暴露于PAF处理后,形成具有非常明显表型的腺泡结构。发现α6-整合素定位错误,根尖染色较多。一些腺泡也显示出不连续的染色(图2A)。这两种表型都表明基底极性的丧失,如文献24,25所示。早期的报告表明α6-整合素在癌症转移中的作用存在争议。α6-整合素与β1-或β4-整合素以二聚体形式存在。已发现α6β4亚基在上...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

讨论

已建立的基于细胞系的模型被广泛用于研究致癌过程。细胞的单层培养继续提供对介导癌细胞特征变化的各种分子信号通路的见解32。关于众所周知的癌基因(如Ras,Myc和突变p53)的作用的研究首先使用单层培养物作为模型系统33,34,35,36。然而,2D培养模型缺乏体内存在的?...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

披露声明

作者声明没有潜在的利益冲突。

致谢

我们感谢IISER浦那显微镜设施提供设备和基础设施以及实验支持。这项研究得到了印度政府生物技术部(DBT)(BT / PR8699 / MED/30 / 1018 / 2013),印度政府科学与工程研究委员会(SERB)(EMR / 2016 / 001974)的资助,部分资金来自IISER,浦那核心资金。A.K.由CSIR-SRF奖学金资助,洛杉矶由DST-INSPIRE奖学金资助,V.C由DBT资助(BT / PR8699 / MED/30 / 1018 / 2013)。

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

材料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 0.05% Trypsin EDTA | Invitrogen | 25300062 | |

| 16% paraformaldehyde | Alfa Aesar | AA433689M | |

| Anti Mouse Alexa Flour 488 | Invitrogen | A11029 | |

| Anti Rabbit Alexa Flour 488 | Invitrogen | A-11008 | |

| BSA | Sigma | A7030 | |

| Chamber Coverglass | Nunc | 155409 | |

| Cholera Toxin | Sigma | C8052-1MG | 1 mg/mL in dH2O |

| Confocal Microscope | Leica | Leica SP8 | |

| DMEM | Gibco | 11965126 | |

| EDTA | Sigma | E6758 | |

| EGF | Sigma | E9644-0.2MG | 100 mg/mL in dH2O |

| F(ab’)2 fragment of antibody raised in goat against mouse antigen | Jackson Immunoresearch | 115-006-006 | |

| GM130 antibody | Abcam | ab52649 | |

| Goat Serum | Abcam | ab7481 | |

| Hoechst | Invitrogen | 33258 | |

| Horse Serum | Gibco | 16050122 | |

| Hydrocortisone | Sigma | H0888 | 1 mg/mL in ethanol |

| Image Processing Software | ImageJ | ||

| Insulin | Sigma | I1882 | 10 mg/mL stock dH2O |

| lrECM (Matrigel) | Corning | 356231 | |

| Mounting reagent (Slow fade Gold Anti-fade) | Invitrogen | S36937 | |

| Nuclear Stain (Hoechst) | Invitrogen | 33258 | |

| PAF | Cayman Chemicals | 91575-58-5 | Methylcarbamyl PAF C-16, procured as a 10 mg/mL in ethanol |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | Lonza | 17-602E | |

| Sodium Azide | Sigma | S2002 | |

| Tris Base | Sigma | B9754 | |

| Triton X-100 | Sigma | T8787 | |

| Tween 20 | Sigma | P9416 | |

| Vimentin antibody | Abcam | ab92547 | |

| α6-integrin antibody | Millipore | MAB1378 |

参考文献

- Lacroix, M., Leclercq, G. Relevance of breast cancer cell lines as models for breast tumours: an update. Breast Cancer Research and Treatment. 83 (3), 249-289 (2004).

- Vargo-Gogola, T., Rosen, J. M. Modelling breast cancer: one size does not fit all. Nature Reviews Cancer. 7 (9), 659-672 (2007).

- Runswick, S. K., O'Hare, M. J., Jones, L., Streuli, C. H., Garrod, D. R. Desmosomal adhesion regulates epithelial morphogenesis and cell positioning. Nature Cell Biology. 3 (9), 823-830 (2001).

- Streuli, C. H., Bailey, N., Bissell, M. J. Control of mammary epithelial differentiation: basement membrane induces tissue-specific gene expression in the absence of cell-cell interaction and morphological polarity. Journal of Cell Biology. 115 (5), 1383-1395 (1991).

- Streuli, C. H., et al. Laminin mediates tissue-specific gene expression in mammary epithelia. Journal of Cell Biology. 129 (3), 591-603 (1995).

- Bissell, M. J., Kenny, P. A., Radisky, D. C. Microenvironmental regulators of tissue structure and function also regulate tumor induction and progression: the role of extracellular matrix and its degrading enzymes. Cold Spring Harbor Symposia on Quantitative Biology. 70, 343-356 (2005).

- Heinrich, E. L., et al. The inflammatory tumor microenvironment, epithelial mesenchymal transition and lung carcinogenesis. Cancer Microenvironment. 5 (1), 5-18 (2012).

- Gonda, T. A., Tu, S., Wang, T. C. Chronic inflammation, the tumor microenvironment and carcinogenesis. Cell Cycle. 8 (13), 2005-2013 (2009).

- Berdyshev, E. V., Schmid, P. C., Krebsbach, R. J., Schmid, H. H. Activation of PAF receptors results in enhanced synthesis of 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG) in immune cells. The FASEB Journal. 15 (12), 2171-2178 (2001).

- Rola-Pleszczynski, M., Stankova, J. Cytokine gene regulation by PGE(2), LTB(4) and PAF. Mediators of Inflammation. 1 (2), 5-8 (1992).

- Bussolati, B., et al. PAF produced by human breast cancer cells promotes migration and proliferation of tumor cells and neo-angiogenesis. The American Journal of Pathology. 157 (5), 1713-1725 (2000).

- Chakravarty, V., et al. Prolonged exposure to platelet activating factor transforms breast epithelial cells. Frontiers in Genetics. 12, 634938(2021).

- Chen, J., et al. Platelet-activating factor receptor-mediated PI3K/AKT activation contributes to the malignant development of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Oncogene. 34 (40), 5114-5127 (2015).

- Chen, J., et al. Feed-forward reciprocal activation of PAFR and STAT3 regulates epithelial-mesenchymal transition in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Research. 75 (19), 4198-4210 (2015).

- Vidi, P. A., Bissell, M. J., Lelievre, S. A. Three-dimensional culture of human breast epithelial cells: the how and the why. Methods in Molecular Biology. 945, 193-219 (2013).

- Debnath, J., Muthuswamy, S. K., Brugge, J. S. Morphogenesis and oncogenesis of MCF-10A mammary epithelial acini grown in three-dimensional basement membrane cultures. Methods. 30 (3), 256-268 (2003).

- Barcellos-Hoff, M. H., Aggeler, J., Ram, T. G., Bissell, M. J. Functional differentiation and alveolar morphogenesis of primary mammary cultures on reconstituted basement membrane. Development. 105 (2), 223-235 (1989).

- Petersen, O. W., Ronnov-Jessen, L., Howlett, A. R., Bissell, M. J. Interaction with basement membrane serves to rapidly distinguish growth and differentiation pattern of normal and malignant human breast epithelial cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 89 (19), 9064-9068 (1992).

- Shaw, K. R., Wrobel, C. N., Brugge, J. S. Use of three-dimensional basement membrane cultures to model oncogene-induced changes in mammary epithelial morphogenesis. Journal of Mammary Gland Biology and Neoplasia. 9 (4), 297-310 (2004).

- Weaver, V. M., Fischer, A. H., Peterson, O. W., Bissell, M. J. The importance of the microenvironment in breast cancer progression: recapitulation of mammary tumorigenesis using a unique human mammary epithelial cell model and a three-dimensional culture assay. Biochemistry and Cell Biology. 74 (6), 833-851 (1996).

- Lee, G. Y., Kenny, P. A., Lee, E. H., Bissell, M. J. Three-dimensional culture models of normal and malignant breast epithelial cells. Nature Methods. 4 (4), 359-365 (2007).

- Bodakuntla, S., Libi, A. V., Sural, S., Trivedi, P., Lahiri, M. N-nitroso-N-ethylurea activates DNA damage surveillance pathways and induces transformation in mammalian cells. BMC Cancer. 14, 287(2014).

- Banerjee, A., et al. A rhodamine derivative as a "lock" and SCN− as a "key": visible light excitable SCN− sensing in living cells. Chemical Communications. 49 (25), 2527-2529 (2013).

- Ren, G., et al. Reduced basal nitric oxide production induces precancerous mammary lesions via ERBB2 and TGFbeta. Scientific Reports. 9 (1), 6688(2019).

- Anandi, L., Chakravarty, V., Ashiq, K. A., Bodakuntla, S., Lahiri, M. DNA-dependent protein kinase plays a central role in transformation of breast epithelial cells following alkylation damage. Journal of Cell Science. 130 (21), 3749-3763 (2017).

- Sonnenberg, A., et al. Integrin alpha 6/beta 4 complex is located in hemidesmosomes, suggesting a major role in epidermal cell-basement membrane adhesion. Journal of Cell Biology. 113 (4), 907-917 (1991).

- Pignatelli, M., Cardillo, M. R., Hanby, A., Stamp, G. W. Integrins and their accessory adhesion molecules in mammary carcinomas: loss of polarization in poorly differentiated tumors. Human Pathology. 23 (10), 1159-1166 (1992).

- Natali, P. G., et al. Changes in expression of alpha 6/beta 4 integrin heterodimer in primary and metastatic breast cancer. British Journal of Cancer. 66 (2), 318-322 (1992).

- Davis, T. L., Cress, A. E., Dalkin, B. L., Nagle, R. B. Unique expression pattern of the alpha6beta4 integrin and laminin-5 in human prostate carcinoma. Prostate. 46 (3), 240-248 (2001).

- Liu, J. S., Farlow, J. T., Paulson, A. K., Labarge, M. A., Gartner, Z. J. Programmed cell-to-cell variability in Ras activity triggers emergent behaviors during mammary epithelial morphogenesis. Cell Reports. 2 (5), 1461-1470 (2012).

- Liu, C. Y., Lin, H. H., Tang, M. J., Wang, Y. K. Vimentin contributes to epithelial-mesenchymal transition cancer cell mechanics by mediating cytoskeletal organization and focal adhesion maturation. Oncotarget. 6 (18), 15966-15983 (2015).

- Kapalczynska, M., et al. 2D and 3D cell cultures-a comparison of different types of cancer cell cultures. Archives of Medical Science. 14 (4), 910-919 (2018).

- Schulze, A., Lehmann, K., Jefferies, H. B., McMahon, M., Downward, J. Analysis of the transcriptional program induced by Raf in epithelial cells. Genes & Development. 15 (8), 981-994 (2001).

- McCarthy, S. A., Samuels, M. L., Pritchard, C. A., Abraham, J. A., McMahon, M. Rapid induction of heparin-binding epidermal growth factor/diphtheria toxin receptor expression by Raf and Ras oncogenes. Genes & Development. 9 (16), 1953-1964 (1995).

- Willis, A., Jung, E. J., Wakefield, T., Chen, X. Mutant p53 exerts a dominant negative effect by preventing wild-type p53 from binding to the promoter of its target genes. Oncogene. 23 (13), 2330-2338 (2004).

- Haupt, S., Raghu, D., Haupt, Y. Mutant p53 drives cancer by subverting multiple tumor suppression pathways. Frontiers in Oncology. 6, 12(2016).

- Langhans, S. A. Three-dimensional in vitro cell culture models in drug discovery and drug repositioning. Frontiers in Pharmacology. 9, 6(2018).

- Edmondson, R., Broglie, J. J., Adcock, A. F., Yang, L. Three-dimensional cell culture systems and their applications in drug discovery and cell-based biosensors. ASSAY and Drug Development Technologies. 12 (4), 207-218 (2014).

- Lv, D., Hu, Z., Lu, L., Lu, H., Xu, X. Three-dimensional cell culture: A powerful tool in tumor research and drug discovery. Oncology Letters. 14 (6), 6999-7010 (2017).

- Jensen, C., Teng, Y. Is it time to start transitioning from 2D to 3D cell culture. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 7, 33(2020).

- Saraiva, D. P., Matias, A. T., Braga, S., Jacinto, A., Cabral, M. G. Establishment of a 3D co-culture with MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell line and patient-derived immune cells for application in the development of immunotherapies. Frontiers in Oncology. 10, 1543(2020).

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

转载和许可

请求许可使用此 JoVE 文章的文本或图形

请求许可探索更多文章

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

版权所属 © 2025 MyJoVE 公司版权所有,本公司不涉及任何医疗业务和医疗服务。