需要订阅 JoVE 才能查看此. 登录或开始免费试用。

Method Article

一种用于研究番茄种子发育的有效清除方案(Solanum lycopersicum L.)

摘要

番茄种子是研究植物繁殖过程中遗传学和发育生物学的重要模型。该协议可用于清除不同发育阶段的番茄种子以观察更精细的胚胎结构。

摘要

番茄(Solanum lycopersicum L.)是全球主要的经济作物之一。番茄种子是研究植物繁殖过程中遗传学和发育生物学的重要模型。番茄种子内更精细的胚胎结构的可视化通常受到种皮粘液、多细胞分层外皮和厚壁胚乳的阻碍,这需要通过费力的包埋切片来解决。更简单的替代方案是采用组织清除技术,使用化学试剂使种子几乎透明。虽然传统的清除程序可以深入了解具有较薄种皮的较小种子,但清除番茄种子在技术上仍然具有挑战性,尤其是在发育后期阶段。

这里介绍的是一种快速且省力的清除方案,用于观察开花后 3 至 23 天胚胎形态接近完成时的番茄种子发育。该方法将广泛用于 拟南芥 的水合氯醛澄清溶液与其他修饰相结合,包括省略福尔马林 - 乙酰醇(FAA)固定,添加次氯酸钠处理种子,去除软化的种皮粘液以及洗涤和真空处理。该方法可用于不同发育阶段番茄种子的高效清除,有助于全面监测突变种子的发育过程,具有良好的空间分辨率。该清除协议也可以应用于茄科其他商业重要物种的深度成像。

引言

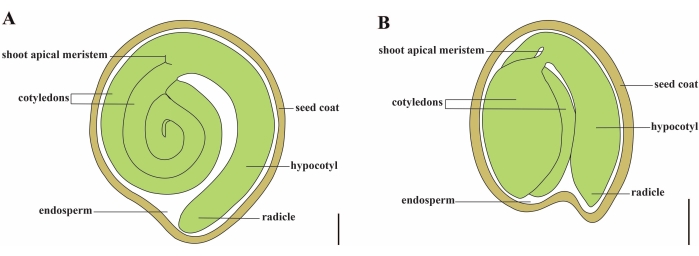

番茄(番茄 )是世界上最重要的蔬菜作物之一,2020年产量为1.868亿吨肉质水果,面积达510万公顷1。它属于大型茄科,约有2,716种2,包括许多具有重要商业意义的作物,如茄子,辣椒,马铃薯和烟草。栽培番茄是一种二倍体物种(2n = 2x = 24),基因组大小约为900 Mb3。长期以来,通过从野生茄属中选择理想的性状,在番 茄 驯化和育种方面做出了巨大努力。番茄遗传学资源中心列出了 5,000 多种番茄种质,全球储存了 80,000 多种番茄种质4.番茄植株在温室中多年生,通过种子繁殖。成熟的番茄种子由三个主要隔室组成:一个成熟的胚胎、残留的细胞型胚乳和一个坚硬的种皮5,6 (图 1A)。双重受精后,细胞型胚乳的发育先于受精卵的发育。在开花后~5-6天(DAF),当胚乳由6至8个细胞核7组成时,首先观察到双细胞前胚。在 茄子松中,胚胎在20 DAF后接近其最终大小,种子在32 DAF8后可以发芽。随着胚胎的发育,胚乳逐渐被吸收,种子中只剩下少量胚乳。残留胚乳由胚根尖端周围的小胚乳和种子其余部分的侧胚乳组成9,10。外种皮由外皮增厚木质化的外表皮发育而来,与外皮残余物的死层形成硬壳以保护胚胎和胚乳5。

图1: Solanum lycopersicum 和 拟南芥中 成熟种子的示意图。 (A)成熟番茄种子的纵向解剖结构。(B)成熟 拟南芥 种子的纵向解剖。成熟的番茄种子的大小大约是 拟南芥 种子的 70 倍。比例尺 = (A) 400 μm, (B) 100 μm。 请点击此处查看此图的大图。

高质量番茄种子的生产取决于胚胎、胚乳和母体种子成分之间的协调11.剖析种子发育中的关键基因和网络需要对突变种子进行深入和完整的表型记录。传统的包埋切片技术,如半薄切片和石蜡切片,被广泛用于番茄种子,以观察胚胎的局部和更精细的结构12,13,14,15。然而,从薄片分析种子发育通常很费力,并且缺乏z轴空间分辨率。相比之下,组织清除是一种快速有效的方法,可以查明最有可能发生的胚胎缺陷的发育阶段16。清除方法通过用一种或多种生化剂均质化折射率来降低内部组织的不透明度16。全组织清除可以在不破坏其完整性的情况下观察植物组织结构,并且清除技术和三维成像的结合已成为获取植物器官形态和发育状态信息的理想解决方案17,18。多年来,种子清除技术已用于各种植物物种,包括拟南芥、大麦和普通贝塔19、20、21、22、23。其中,全镶样胚珠清除技术因其体积小、种皮细胞4-5层、核型胚乳24、25等特点,成为研究拟南芥种子发育的有效方法。随着不同清除混合物的不断更新,例如Hoyer溶液26的出现,尽管大麦胚珠的胚乳占种子的大部分,但大麦胚珠的内部结构以高度清晰的方式成像。甜菜的胚胎发生可以通过清除结合真空处理和盐酸软化来观察19。尽管如此,与上述物种不同,尚未报道通过清除番茄种子协议进行的胚胎学观察。这阻碍了对西红柿胚胎和种子发育的详细调查。

水合氯醛通常用作澄清溶液,其允许浸没的组织和细胞在不同的光学平面上显示,并基本上保留细胞或组织成分27,28,29。基于水合氯醛的清除方案已成功用于种子的全安装清除,以观察拟南芥21,28的胚胎和胚乳。然而,这种清除溶液在清除番茄种子方面效率不高,番茄种子比拟南芥种子更不透水。物理屏障包括:(1)番茄外皮在3至15 DAF 30,31处有近20个细胞层,(2)番茄胚乳是细胞型,而不是核型32,(3)番茄种子的大小约为70倍33,34和(4)产生大量的种皮粘液,这阻止了清除试剂的渗透并影响了胚胎细胞的可视化。

因此,本报告提出了一种优化的基于水合氯醛的清除方法,用于在不同阶段对番茄种子进行整体安装清除,该方法可以对胚胎发育过程进行深度成像(图2)。

研究方案

1. 溶液的制备

- 通过在 50 mL 离心管中加入 2.5 mL 37% 甲醛、2.5 mL 冰醋酸和 45 mL 70% 乙醇来制备 FAA 固定剂。涡旋并将其储存在4°C。 使用前新鲜制备FAA固定剂。

注意:37%的甲醛具有腐蚀性,如果暴露或吸入,可能会致癌。固定剂必须在通风橱中进行,同时穿戴适当的个人防护设备。 - 通过在用锡箔包裹的 100 mL 玻璃瓶中加入 5 mL 100% 甘油、40 g 水合氯醛和 10 mL 蒸馏水来制备透明溶液。使用磁力搅拌器在室温下溶解过夜。制备的溶液可以在4°C下储存长达6个月。

注意:水合氯醛具有致癌性,有刺激性气味。在通风橱中进行实验并穿戴适当的个人防护设备。水合氯醛在空气中易潮解,不宜大量储存。清除溶液暴露在光线下会分解,应避光。 - 通过在 50 mL 离心管中加入 10 mL 6% 次氯酸钠、40 mL 蒸馏水和 50 μL 吐温-20 来制备消毒剂溶液。涡旋并在室温下储存。使用前新鲜准备消毒液。

注:放置时间较长的次氯酸钠有效氯含量可能会降低,可根据实际情况增加6%次氯酸钠的含量。

2. 种子采集

- 播种番茄种子(S. lycopersicum L. cv. Micro-Tom,见 材料表)在8厘米×8厘米×8厘米方形盆中,充满花营养土壤和基质(v / v)的1:1混合物(见 材料表),并在24±2°C(白天)和18±2°C(夜间)下生长在16/8小时光照/黑暗期的生长室中生长, 60%-70%相对湿度,光强度为4,000勒克斯。 大约6周后,植物进入开花期。

- 标记开花时独立花的开花日期(花瓣开放角度为90°),并记录开花后的第二天(DAF)。

- 从 3 到 23 株 DAF 番茄植物中收获果实,并立即将它们放在冰上。将 3 到 23 DAF 的果实(种子或胚胎)分为早期(3-10 DAF)、中期(11-16 DAF)和晚期(17-23 DAF)水果(种子或胚胎)。

注意:不要一次收集太多水果,并确保每个水果中的种子在1小时内剥离以进行进一步处理。 - 对于早期水果,将水果打碎并将其放在载玻片上,并在立体显微镜下用精密镊子(见 材料表)以1x至4x放大倍率仔细收集新鲜种子。对于中后期水果,将水果掰开,用精密镊子直接收集新鲜种子。

3. 水合氯醛基种子清除

注意:在本研究中比较了常规35 和优化方案的种子清除效率。

- 使用传统协议进行清算

- 立即将新鲜种子(在步骤2.4中获得)放入含有1.5mL FAA固定剂的2 mL离心管中,并在室温下在轨道振荡器(5 rpm,参见 材料表)上孵育4小时。

- 将这些种子在70%,95%和100%乙醇(v / v)的乙醇系列中脱水1小时,分别在轨道振荡器(5rpm)上。

- 将种子放入载玻片上的3-5滴透明溶液(~100μL)中,并用盖玻片轻轻覆盖样品。用单个凹面载玻片(见 材料表)代替载玻片,用于中后期种子。

- 将这些载玻片或单个凹面载玻片在室温下保持30分钟(3 DAF),2小时(6 DAF),1天(9 DAF),3天(12 DAF)或7天(14至22 DAF),具体取决于种子材料的发育阶段(材料越年轻,清除速度越快)。

- 用配备数码相机的微分干涉对比(DIC)显微镜(参见 材料表)以10x,20x和40x放大倍率观察样品。实时调整和优化每个样品和捕获图像的透射光亮度、DIC滑块和聚光镜孔径。

- 使用优化的协议进行清算

- 将新鲜种子(在步骤2.4中获得)直接放入含有1.5 mL消毒剂溶液的2 mL离心管中(步骤1.3)。

注意:在2 mL离心管中收集的种子数量根据种子的发育阶段而变化。 表 1 中列出了详细信息。 - 将样品在室温下在轨道振荡器(30rpm)上孵育3至50分钟,直到最里面的种皮轮廓清晰可见。丢弃消毒液。

注意:所需的孵化时间取决于种子发育阶段(种子越晚,孵育时间越长)。 表 1 中列出了详细信息。 - 对于中晚期种子,将种子转移到载玻片上,并在体视显微镜下以1x至4x放大倍率用镊子和解剖针去除种子粘液。使用镊子将种子转移回原始离心管中。

注意:对于早期种子,此步骤不是必需的。 - 用 1.5 mL 去离子水洗涤种子 5 次,每次 10 秒。丢弃去离子水。

- 加入2×种子体积的澄清溶液,然后用真空泵真空处理0至50分钟(表1)(见 材料表)。间歇真空处理,每次真空处理间隔10分钟,间隔10分钟。

- 用种子体积的2×的新鲜澄清溶液代替。将含有种子的2 mL离心管保持在室温下,避光保存30分钟至7天,以利于清除(表1)。在孵育期间,对于晚期胚胎,每天用新鲜溶液替换透明溶液,并对种子进行真空处理10分钟。

- 在载玻片或单凹载玻片上制备清除的种子,并使用配备数码相机的DIC显微镜以10x,20x和40x放大倍率进行观察。实时调整和优化每个样品和捕获图像的透射光亮度、DIC滑块和聚光镜孔径。

- 将新鲜种子(在步骤2.4中获得)直接放入含有1.5 mL消毒剂溶液的2 mL离心管中(步骤1.3)。

结果

当使用拟南芥等常规方法清除番茄种子时,致密的胚乳细胞在3 DAF和6 DAF下阻止了早期番茄胚胎的可视化(图3A,B)。随着胚胎总体积的增加,球状胚胎在9 DAF处几乎无法区分(图3C)。然而,随着种子尺寸的不断增加,其渗透性降低,导致12 DAF处的心脏胚胎模糊(图3D)。从13 DAF开始,种子粘液和种皮逐渐致密?...

讨论

与机械切片相比,清除技术对于三维成像更有利,因为它保留了植物组织或器官的完整性16。由于化学溶液更容易渗透,传统的澄清方案通常仅限于小样品。番茄种子是组织清除的一个有问题的样品,因为它的大小比拟南芥种子大约 70 倍,并且具有更多的渗透屏障。拟南芥种皮由四到五个活细胞层组成,这些活细胞层来自外皮和内皮24。然而,与

披露声明

作者没有利益冲突需要披露。

致谢

作者感谢乐杰博士和宋秀芬博士分别对微分干涉对比显微镜和常规清除方法的有益建议。这项研究由中国国家自然科学基金(31870299)和中国科学院青年创新促进会资助。图 2 是使用 BioRender.com 创建的。

材料

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 1,000 µL pipette | GILSON | FA10006M | |

| 1,000 µL pipette tips | Corning | T-1000-B | |

| 2 ml centrifuge tube | Axygen | MCT-200-C | |

| 37% formaldehyde | DAMAO | 685-2013 | |

| 5,000 µL pipette | Eppendorf | 3120000275 | |

| 5,000 µL pipette tips | biosharp | BS-5000-TL | |

| 50 ml centrifuge tube | Corning | 430829 | |

| Absolute Ethanol | BOYUAN | 678-2002 | |

| Bottle glass | Fisher | FB800-100 | |

| Chloral Hydrate | Meryer | M13315-100G | |

| Coverslip | Leica | 384200 | |

| DIC microscope | Zeiss | Axio Imager A1 | 10x, 20x and 40x magnification |

| Disinfectant | QIKELONGAN | 17-9185 | |

| Dissecting needle | Bioroyee | 17-9140 | |

| Flower nutrient soil | FANGJIE | ||

| Forceps | HAIOU | 4-94 | |

| Glacial Acetic Acid | BOYUAN | 676-2007 | |

| Glycerol | Solarbio | G8190 | |

| Magnetic stirrer | IKA | RET basic | |

| Micro-Tom | Tomato Genetics Resource Center | LA3911 | |

| Orbital shaker | QILINBEIER | QB-206 | |

| Seeding substrate | PINDSTRUP | LV713/018-LV252 | Screening:0-10 mm |

| Single concave slide | HUABODEYI | HBDY1895 | |

| Slide | Leica | 3800381 | |

| Stereomicroscope | Leica | S8 APO | 1x to 4x magnification |

| Tin foil | ZAOWUFANG | 613 | |

| Tween 20 | Sigma | P1379 | |

| Vacuum pump | SHIDING | SHB-III | |

| Vortex meter | Silogex | MX-S |

参考文献

- . FAOSTAT Available from: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (2022)

- Olmstead, R. G., Bohs, L. A summary of molecular systematic research in Solanaceae: 1982-2006. Acta Horticulturae. 745, 255-268 (2007).

- Consortium, T. G. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature. 485 (7400), 635-641 (2012).

- Ebert, A. W., Chou, Y. Y. The tomato collection maintained by AVRDC - The World Vegetable Center: composition, germplasm dissemination and use in breeding. Acta Horticulturae. 1101, 169-176 (2015).

- Hilhorst, H., Groot, S., Bino, R. J. The tomato seed as a model system to study seed development and germination. Acta Botanica Neerlandica. 47, 169-183 (1998).

- Chaban, I. A., Gulevich, A. A., Kononenko, N. V., Khaliluev, M. R., Baranova, E. N. Morphological and structural details of tomato seed coat formation: A different functional role of the inner and outer epidermises in unitegmic ovule. Plants-Basel. 11 (9), 1101 (2022).

- Iwahori, S. High temperature injuries in tomato. V. Fertilization and development of embryo with special reference to the abnormalities caused by high temperature. Journal of The Japanese Society for Horticultural Science. 35 (4), 379-386 (1966).

- Xiao, H., et al. Integration of tomato reproductive developmental landmarks and expression profiles, and the effect of SUN. on fruit shape. BMC Plant Biology. 9 (1), 49 (2009).

- Karssen, C. M., Haigh, A. M., Toorn, P., Weges, R., Taylorson, R. B. Physiological mechanisms involved in seed priming. Recent advances in the development and germination of seeds. NATO ASI Series. 187, (1989).

- Nonogaki, H. Seed dormancy and germination-emerging mechanisms and new hypotheses. Frontiers in Plant Science. 5, 233 (2014).

- Doll, N. M., Ingram, G. C. Embryo-endosperm interactions. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 73, 293-321 (2022).

- Serrani, J. C., Fos, M., Atarés, A., García-Martínez, J. L. Effect of gibberellin and auxin on parthenocarpic fruit growth induction in the cv micro-tom of tomato. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 26 (3), 211-221 (2007).

- Yang, C., et al. A regulatory gene induces trichome formation and embryo lethality in tomato. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 108 (29), 11836-11841 (2011).

- Goetz, S., et al. Role of cis-12-oxo-phytodienoic acid in tomato embryo development. Plant Physiology. 158 (4), 1715-1727 (2012).

- Ko, H. Y., Ho, L. H., Neuhaus, H. E., Guo, W. J. Transporter SlSWEET15 unloads sucrose from phloem and seed coat for fruit and seed development in tomato. Plant Physiology. 187 (4), 2230-2245 (2021).

- Richardson, D. S., Lichtman, J. W. Clarifying tissue clearing. Cell. 162 (2), 246-257 (2015).

- Kurihara, D., Mizuta, Y., Sato, Y., Higashiyama, T. ClearSee: A rapid optical clearing reagent for whole-plant fluorescence imaging. Development. 142 (23), 4168-4179 (2015).

- Vieites-Prado, A., Renier, N. Tissue clearing and 3D imaging in developmental biology. Development. 148 (18), (2021).

- Kwiatkowska, M., Kadłuczka, D., Wędzony, M., Dedicova, B., Grzebelus, E. Refinement of a clearing protocol to study crassinucellate ovules of the sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L., Amaranthaceae). Plant Methods. 15, 71 (2019).

- Ponitka, A., Ślusarkiewicz-Jarzina, A. Cleared-ovule technique used for rapid access to early embryo development in Secale cereale × Zea mays crosses. Acta Biologica Cracoviensia. Series Botanica. 46, 133-137 (2014).

- Ceccato, L., et al. Maternal control of PIN1 is required for female gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. PLoS One. 8 (6), 66148 (2013).

- Wilkinson, L. G., Tucker, M. R. An optimised clearing protocol for the quantitative assessment of sub-epidermal ovule tissues within whole cereal pistils. Plant Methods. 13, 67 (2017).

- Hedhly, A., Vogler, H., Eichenberger, C., Grossniklaus, U. Whole-mount clearing and staining of Arabidopsis flower organs and Siliques. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (134), e56441 (2018).

- Creff, A., Brocard, L., Ingram, G. A mechanically sensitive cell layer regulates the physical properties of the Arabidopsis seed coat. Nature Communications. 6, 6382 (2015).

- Yang, T., et al. The B3 domain-containing transcription factor ZmABI19 coordinates expression of key factors required for maize seed development and grain filling. Plant Cell. 33 (1), 104-128 (2021).

- Anderson, L. E. Hoyer's solution as a rapid permanent mounting medium for bryophytes. Bryologist. 57 (3), 242-244 (1954).

- Herr, J. M. A new clearing-squash technique for the study of ovule development in angiosperms. American Journal of Botany. 58 (8), 785-790 (1971).

- Yadegari, R., et al. Cell differentiation and morphogenesis are uncoupled in Arabidopsis raspberry embryos. The Plant Cell. 6 (12), 1713-1729 (1995).

- Grini, P. E., Jurgens, G., Hulskamp, M. Embryo and endosperm development is disrupted in the female gametophytic capulet mutants of Arabidopsis. Genetics. 162 (4), 1911-1925 (2002).

- Kataoka, K., Uemachi, A., Yazawa, S. Fruit growth and pseudoembryo development affected by uniconazole, an inhibitor of gibberellin biosynthesis, in pat-2 and auxin-Induced parthenocarpic tomato fruits. Scientia Horticulturae. 98 (1), 9-16 (2003).

- de Jong, M., Wolters-Arts, M., Feron, R., Mariani, C., Vriezen, W. H. The Solanum lycopersicum auxin response factor 7 (SlARF7) regulates auxin signaling during tomato fruit set and development. Plant Journal. 57 (1), 160-170 (2009).

- Roth, M., Florez-Rueda, A. M., Paris, M., Stadler, T. Wild tomato endosperm transcriptomes reveal common roles of genomic imprinting in both nuclear and cellular endosperm. Plant Journal. 95 (6), 1084-1101 (2018).

- Orsi, C. H., Tanksley, S. D. Natural variation in an ABC transporter gene associated with seed size evolution in tomato species. PLoS Genetics. 5 (1), 1000347 (2009).

- Herridge, R. P., Day, R. C., Baldwin, S., Macknight, R. C. Rapid analysis of seed size in Arabidopsis for mutant and QTL discovery. Plant Methods. 7 (1), 3 (2011).

- Xu, T. T., Ren, S. C., Song, X. F., Liu, C. M. CLE19 expressed in the embryo regulates both cotyledon establishment and endosperm development in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany. 66 (17), 5217-5227 (2015).

- Ghadiri Alamdari, N., Salmasi, S., Almasi, H. Tomato seed mucilage as a new source of biodegradable film-forming material: effect of glycerol and cellulose nanofibers on the characteristics of resultant films. Food and Bioprocess Technology. 14 (12), 2380-2400 (2021).

- Gardner, R. O. An overview of botanical clearing technique. Stain Technology. 50 (2), 99-105 (1975).

- Beresniewicz, M. M., Taylor, A. G., Goffinet, M. C., Terhune, B. T. Characterization and location of a semipermeable layer in seed coats of leek and onion (Liliaceae), tomato and pepper (Solanaceae). Seed Science and Technology. 23 (1), 123-134 (1995).

- Stebbins, G. L. A bleaching and clearing method for plant tissues. Science. 87 (2245), 21-22 (1938).

- Debenham, E. M. A modified technique for the microscopic examination of the xylem of whole plants or plant organs. Annals of Botany. 3 (2), 369-373 (1939).

- Morley, T. Accelerated clearing of plant leaves by NaOH in association with oxygen. Stain Technology. 43 (6), 315-319 (1968).

转载和许可

请求许可使用此 JoVE 文章的文本或图形

请求许可探索更多文章

This article has been published

Video Coming Soon

版权所属 © 2025 MyJoVE 公司版权所有,本公司不涉及任何医疗业务和医疗服务。