A subscription to JoVE is required to view this content. Sign in or start your free trial.

Method Article

An Efficient Clearing Protocol for the Study of Seed Development in Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.)

In This Article

Summary

The tomato seed is an important model for studying genetics and developmental biology during plant reproduction. This protocol is useful for clearing tomato seeds at different developmental stages to observe the finer embryonic structure.

Abstract

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L.) is one of the major cash crops worldwide. The tomato seed is an important model for studying genetics and developmental biology during plant reproduction. Visualization of finer embryonic structure within a tomato seed is often hampered by seed coat mucilage, multi-cell-layered integument, and a thick-walled endosperm, which needs to be resolved by laborious embedding-sectioning. A simpler alternative is to employ tissue clearing techniques that turn the seed almost transparent using chemical agents. Although conventional clearing procedures allow deep insight into smaller seeds with a thinner seed coat, clearing tomato seeds continues to be technically challenging, especially in the late developmental stages.

Presented here is a rapid and labor-saving clearing protocol to observe tomato seed development from 3 to 23 days after flowering when embryonic morphology is nearly complete. This method combines chloral hydrate-based clearing solution widely used in Arabidopsis with other modifications, including the omission of Formalin-Aceto-Alcohol (FAA) fixation, the addition of sodium hypochlorite treatment of seeds, removal of the softened seed coat mucilage, and washing and vacuum treatment. This method can be applied for efficient clearing of tomato seeds at different developmental stages and is useful in full monitoring of the developmental process of mutant seeds with good spatial resolution. This clearing protocol may also be applied to deep imaging of other commercially important species in the Solanaceae.

Introduction

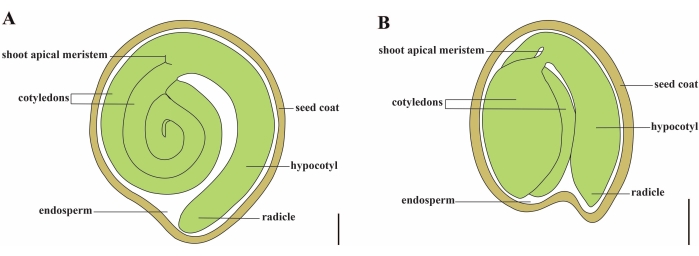

Tomato (S. lycopersicum L.) is one of the most important vegetable crops around the world, with an output of 186.8 million tons of fleshy fruits from 5.1 million hectares in 20201. It belongs to the large Solanaceae family with about 2,716 species2, including many commercially important crops such as eggplant, peppers, potato, and tobacco. The cultivated tomato is a diploid species (2n = 2x = 24) with a genome size of approximately 900 Mb3. For a long time, great effort has been made toward tomato domestication and breeding by selecting desirable traits from wild Solanum spp. There are over 5,000 tomato accessions listed in the Tomato Genetics Resource Center and more than 80,000 germplasm of tomatoes are stored worldwide4. The tomato plant is perennial in the greenhouse and propagates by seeds. A mature tomato seed consists of three major compartments: a full-grown embryo, residual cellular-type endosperm, and a hard seed coat5,6 (Figure 1A). After double fertilization, the development of cellular-type endosperm precedes the development of zygotes. At ~5-6 days after flowering (DAF), two-celled proembryo is first observed when the endosperm consists of six to eight nuclei7. In Solanum pimpinellifolium, the embryo approaches its final size after 20 DAF, and seeds are viable for germination after 32 DAF8. As the embryo develops, the endosperm is gradually absorbed and only a small amount of endosperm remains in the seed. The residual endosperm consists of micropylar endosperm surrounding the radicle tip, and lateral endosperm in the rest of the seed9,10. The outer seed coat is developed from thickened and lignified outer epidermis of the integument, and with the dead layers of integument remnants, they form a hard shell to protect the embryo and endosperm5.

Figure 1: Schematic representation of a mature seed in Solanum lycopersicum and Arabidopsis thaliana. (A) Longitudinal anatomy of a mature tomato seed. (B) Longitudinal anatomy of a mature Arabidopsis seed. A mature tomato seed is approximately 70 times larger in size than an Arabidopsis seed. Scale bars = (A) 400 µm, (B) 100 µm. Please click here to view a larger version of this figure.

Production of high-quality tomato seeds depends on the coordination between the embryo, the endosperm, and the maternal seed components11. Dissecting key genes and networks in seed development requires a deep and full-track phenotypic recording of mutant seeds. Conventional embedding-sectioning techniques, such as the semi-thin section and paraffin section, are widely applied to tomato seeds to observe the local and finer structures of the embryo12,13,14,15. However, analyzing the seed development from thin sections is usually laborious and lacks z-axis spatial resolution. In comparison, tissue clearing is a fast and efficient method to pinpoint the developmental stage of embryo defects that are most likely to occur16. The clearing method reduces the opaqueness of internal tissue by homogenizing the refractive index with one or more biochemical agents16. Whole tissue clearing allows observation of a plant tissue structure without destroying its integrity, and the combination of clearing technology and three-dimensional imaging has become an ideal solution to obtain information on the morphology and developmental state of a plant organ17,18. Over the years, seed clearing techniques have been used in various plant species, including Arabidopsis thaliana, Hordeum vulgare, and Beta vulgaris19,20,21,22,23. Among these, the whole-mount ovule clearing technology has been an efficient approach to studying seed development of Arabidopsis, due to its small size, 4-5 layers of the seed coat cell, and the nuclear-type endosperm24,25. With the continuous updating of different clearing mixtures, such as the emergence of Hoyer's solution26, internal structures of the barley ovule were imaged with a high degree of clarity although its endosperm makes up the bulk of the seeds. Embryogenesis of sugar beet can be observed by clearing combined with vacuum treatment and softening with hydrochloric acid19. Nonetheless, unlike the species mentioned above, embryological observations by clearing protocols in tomato seeds have not been reported. This prevents detailed investigation into the embryonic and seed development of tomatoes.

Chloral hydrate is commonly used as a clearing solution that allows the immersed tissues and cells to be displayed on different optical planes, and substantially preserves the cells or tissue components27,28,29. Chloral hydrate-based clearing protocol has been successfully used for the whole-mount clearing of seeds to observe the embryo and endosperm of Arabidopsis21,28. However, this clearing solution is not efficient in clearing tomato seeds, which are more impermeable than Arabidopsis seeds. The physical barriers include: (1) the tomato integument has nearly 20 cell layers at 3 to 15 DAF30,31, (2) the tomato endosperm is cellular-type, not nuclear-type32, and (3) tomato seeds are about 70 times larger in size33,34 and (4) produce large amounts of seed coat mucilage, which blocks the penetration of clearing reagents and affects the visualization of embryo cells.

Therefore, this report presents an optimized chloral hydrate-based clearing method for whole-mount clearing of tomato seeds at different stages, which allows deep imaging of the embryo development process (Figure 2).

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Protocol

1. Preparation of solutions

- Prepare FAA fixative by adding 2.5 mL of 37% formaldehyde, 2.5 mL of glacial acetic acid, and 45 mL of 70% ethanol in a 50 mL centrifuge tube. Vortex and store it at 4 °C. Freshly prepare FAA fixative just before use.

CAUTION: 37% formaldehyde is corrosive and potentially carcinogenic if exposed or inhaled. The fixative must be performed in a fume hood while wearing appropriate personal protective equipment. - Prepare clearing solution by adding 5 mL of 100% glycerol, 40 g chloral hydrate, and 10 mL of distilled water in a 100 mL glass bottle wrapped with tin foil. Dissolve using a magnetic stirrer overnight at room temperature. The prepared solution can be stored at 4 °C for up to 6 months.

CAUTION: Chloral hydrate is carcinogenic and has a pungent smell. Perform the experiment in a fume hood and wear appropriate personal protective equipment. Chloral hydrate is easy to deliquesce in the air and should not be stored in large quantities. The clearing solution can decompose when exposed to light and should be kept away from light. - Prepare the disinfectant solution by adding 10 mL of 6% sodium hypochlorite, 40 mL distilled water, and 50 µL Tween-20 in a 50 mL centrifuge tube. Vortex and store it at room temperature. Freshly prepare the disinfectant solution just before use.

NOTE: The effective chlorine content of sodium hypochlorite that has been placed for a long time may decrease, and the content of 6% sodium hypochlorite can be increased according to the actual situation.

2. Seed collection

- Sow tomato seeds (S. lycopersicum L. cv. Micro-Tom, see Table of Materials) in 8 cm × 8 cm × 8 cm square basins full with a 1:1 mixture of flower nutrient soil and substrate (v/v) (see Table of Materials), and grow in a growth room with 16/8 h light/dark periods at 24 ± 2 °C (day) and 18 ± 2 °C (night), 60%-70% relative humidity, and a light intensity of 4,000 Lux. Approximately 6 weeks later, plants entered the flowering stage.

- Tag the flowering date of independent flowers at anthesis (opening angle of the petals is 90°), and record the day after flowering (DAF).

- Harvest the fruits from 3 to 23 DAF tomato plants and immediately put them on ice. Divide fruits (seeds or embryos) from 3 to 23 DAF into early (3-10 DAF), middle (11-16 DAF), and late (17-23 DAF) fruits (seeds or embryos).

NOTE: Do not collect too many fruits at a time and ensure that the seeds in each fruit are stripped within 1 h for further treatment. - For early fruits, break the fruit and put it on a slide, and collect fresh seeds carefully with precision forceps under the stereomicroscope (see Table of Materials) at 1x to 4x magnification. For middle and late fruits, break the fruit and directly collect fresh seeds using precision forceps.

3. Chloral hydrate-based clearing of seeds

NOTE: Conventional35 and optimized protocols were compared in this study for their seed clearing efficiency.

- Clearing using a conventional protocol

- Place fresh seeds (obtained in step 2.4) immediately in a 2 mL centrifuge tube containing 1.5 mL FAA fixative and incubate on an orbital shaker (5 rpm, see Table of Materials) for 4 h at room temperature.

- Dehydrate these seeds in an ethanol series of 70%, 95%, and 100% ethanol (v/v) for 1 h each on an orbital shaker (5 rpm).

- Place the seeds in 3-5 drops of clearing solution (~100 µL) on the slide and gently cover the sample with a coverslip. Replace the slide with a single concave slide (see Table of Materials) for middle and late seeds.

- Keep these slides or single concave slides at room temperature for 30 min (3 DAF), 2 h (6 DAF), 1 day (9 DAF), 3 days (12 DAF), or 7 days (14 to 22 DAF) depending on the developmental stages of the seed material (the younger the materials, the faster the clearing speed).

- Observe the samples with a differential interference contrast (DIC) microscope equipped with a digital camera (see Table of Materials) at 10x, 20x, and 40x magnification. Adjust and optimize the transmitted light brightness, DIC slider, and condenser aperture in real time for each sample and capture images.

- Clearing using the optimized protocol

- Place fresh seeds (obtained in step 2.4) directly into a 2 mL centrifuge tube containing 1.5 mL disinfectant solution (step 1.3).

NOTE: The number of seeds collected in the 2 mL centrifuge tube varies according to the developmental stage of the seeds. Details are listed in Table 1. - Incubate the samples on an orbital shaker (30 rpm) at room temperature for 3 to 50 min until the innermost seed coat outline is clearly visible. Discard the disinfectant solution.

NOTE: The incubation time required depends on the seed developmental stage (the later the seeds, the longer will be the incubation time). Details are listed in Table 1. - For middle and late seeds, transfer the seeds onto a slide and remove the seed mucilage with forceps and a dissecting needle under a stereomicroscope at 1x to 4x magnification. Transfer the seeds back into the original centrifuge tube using forceps.

NOTE: This step is not necessary for early seeds. - Wash the seeds 5x with 1.5 mL deionized water, 10 s each time. Discard the deionized water.

- Add a clearing solution of 2 × the volume of the seeds, followed by vacuum treatment for 0 to 50 min (Table 1) with a vacuum pump (see Table of Materials). Intermittent vacuum treatment is performed with each vacuum treatment for 10 min spaced at 10 min intervals.

- Replace with a fresh clearing solution of 2 × the volume of the seeds. Keep the 2 mL centrifuge tube containing the seeds at room temperature and protected from light for 30 min to 7 days to facilitate clearing (Table 1). During the incubation, for late embryos, replace the clearing solution daily with fresh solution and subject the seeds to vacuum treatment for 10 min.

- Prepare the cleared seeds on slides or single-concave slides and observe with the DIC microscope equipped with a digital camera at 10x, 20x, and 40x magnification. Adjust and optimize the transmitted light brightness, DIC slider, and condenser aperture in real time for each sample and capture images.

- Place fresh seeds (obtained in step 2.4) directly into a 2 mL centrifuge tube containing 1.5 mL disinfectant solution (step 1.3).

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Results

When tomato seeds were cleared using a conventional method as in Arabidopsis, dense endosperm cells blocked the visualization of early tomato embryos at 3 DAF and 6 DAF (Figure 3A,B). As the total volume of the embryo increased, a globular embryo was barely distinguishable at 9 DAF (Figure 3C). However, as the seed size continued to increase, its permeability decreased, resulting in a fuzzy heart embryo at 12 DAF (F...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Discussion

Compared to mechanical sectioning, the clearing technology is more advantageous for three-dimensional imaging as it retains the integrity of plant tissues or organs16. Conventional clearing protocols are often limited to small samples due to easier penetration of chemical solutions. Tomato seed is a problematic sample for tissue clearing because it is about 70 times larger than an Arabidopsis seed in size and has more permeability barriers. The Arabidopsis seed coat is composed o...

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Disclosures

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Jie Le and Dr. Xiufen Song for their helpful suggestions on differential interference contrast microscopy and conventional clearing method, respectively. This research was financed by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31870299) and the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences. Figure 2 was created with BioRender.com.

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Materials

| Name | Company | Catalog Number | Comments |

| 1,000 µL pipette | GILSON | FA10006M | |

| 1,000 µL pipette tips | Corning | T-1000-B | |

| 2 ml centrifuge tube | Axygen | MCT-200-C | |

| 37% formaldehyde | DAMAO | 685-2013 | |

| 5,000 µL pipette | Eppendorf | 3120000275 | |

| 5,000 µL pipette tips | biosharp | BS-5000-TL | |

| 50 ml centrifuge tube | Corning | 430829 | |

| Absolute Ethanol | BOYUAN | 678-2002 | |

| Bottle glass | Fisher | FB800-100 | |

| Chloral Hydrate | Meryer | M13315-100G | |

| Coverslip | Leica | 384200 | |

| DIC microscope | Zeiss | Axio Imager A1 | 10x, 20x and 40x magnification |

| Disinfectant | QIKELONGAN | 17-9185 | |

| Dissecting needle | Bioroyee | 17-9140 | |

| Flower nutrient soil | FANGJIE | ||

| Forceps | HAIOU | 4-94 | |

| Glacial Acetic Acid | BOYUAN | 676-2007 | |

| Glycerol | Solarbio | G8190 | |

| Magnetic stirrer | IKA | RET basic | |

| Micro-Tom | Tomato Genetics Resource Center | LA3911 | |

| Orbital shaker | QILINBEIER | QB-206 | |

| Seeding substrate | PINDSTRUP | LV713/018-LV252 | Screening:0-10 mm |

| Single concave slide | HUABODEYI | HBDY1895 | |

| Slide | Leica | 3800381 | |

| Stereomicroscope | Leica | S8 APO | 1x to 4x magnification |

| Tin foil | ZAOWUFANG | 613 | |

| Tween 20 | Sigma | P1379 | |

| Vacuum pump | SHIDING | SHB-III | |

| Vortex meter | Silogex | MX-S |

References

- FAOSTAT. , Available from: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (2022).

- Olmstead, R. G., Bohs, L. A summary of molecular systematic research in Solanaceae: 1982-2006. Acta Horticulturae. 745, 255-268 (2007).

- Consortium, T. G. The tomato genome sequence provides insights into fleshy fruit evolution. Nature. 485 (7400), 635-641 (2012).

- Ebert, A. W., Chou, Y. Y. The tomato collection maintained by AVRDC - The World Vegetable Center: composition, germplasm dissemination and use in breeding. Acta Horticulturae. 1101, 169-176 (2015).

- Hilhorst, H., Groot, S., Bino, R. J. The tomato seed as a model system to study seed development and germination. Acta Botanica Neerlandica. 47, 169-183 (1998).

- Chaban, I. A., Gulevich, A. A., Kononenko, N. V., Khaliluev, M. R., Baranova, E. N. Morphological and structural details of tomato seed coat formation: A different functional role of the inner and outer epidermises in unitegmic ovule. Plants-Basel. 11 (9), 1101(2022).

- Iwahori, S. High temperature injuries in tomato. V. Fertilization and development of embryo with special reference to the abnormalities caused by high temperature. Journal of The Japanese Society for Horticultural Science. 35 (4), 379-386 (1966).

- Xiao, H., et al. Integration of tomato reproductive developmental landmarks and expression profiles, and the effect of SUN. on fruit shape. BMC Plant Biology. 9 (1), 49(2009).

- Karssen, C. M., Haigh, A. M., Toorn, P., Weges, R. Physiological mechanisms involved in seed priming. Recent advances in the development and germination of seeds. NATO ASI Series. Taylorson, R. B. 187, Springer. Boston, MA. (1989).

- Nonogaki, H. Seed dormancy and germination-emerging mechanisms and new hypotheses. Frontiers in Plant Science. 5, 233(2014).

- Doll, N. M., Ingram, G. C. Embryo-endosperm interactions. Annual Review of Plant Biology. 73, 293-321 (2022).

- Serrani, J. C., Fos, M., Atarés, A., García-Martínez, J. L. Effect of gibberellin and auxin on parthenocarpic fruit growth induction in the cv micro-tom of tomato. Journal of Plant Growth Regulation. 26 (3), 211-221 (2007).

- Yang, C., et al. A regulatory gene induces trichome formation and embryo lethality in tomato. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences USA. 108 (29), 11836-11841 (2011).

- Goetz, S., et al. Role of cis-12-oxo-phytodienoic acid in tomato embryo development. Plant Physiology. 158 (4), 1715-1727 (2012).

- Ko, H. Y., Ho, L. H., Neuhaus, H. E., Guo, W. J. Transporter SlSWEET15 unloads sucrose from phloem and seed coat for fruit and seed development in tomato. Plant Physiology. 187 (4), 2230-2245 (2021).

- Richardson, D. S., Lichtman, J. W. Clarifying tissue clearing. Cell. 162 (2), 246-257 (2015).

- Kurihara, D., Mizuta, Y., Sato, Y., Higashiyama, T. ClearSee: A rapid optical clearing reagent for whole-plant fluorescence imaging. Development. 142 (23), 4168-4179 (2015).

- Vieites-Prado, A., Renier, N. Tissue clearing and 3D imaging in developmental biology. Development. 148 (18), (2021).

- Kwiatkowska, M., Kadłuczka, D., Wędzony, M., Dedicova, B., Grzebelus, E. Refinement of a clearing protocol to study crassinucellate ovules of the sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L., Amaranthaceae). Plant Methods. 15, 71(2019).

- Ponitka, A., Ślusarkiewicz-Jarzina, A. Cleared-ovule technique used for rapid access to early embryo development in Secale cereale × Zea mays crosses. Acta Biologica Cracoviensia. Series Botanica. 46, 133-137 (2014).

- Ceccato, L., et al. Maternal control of PIN1 is required for female gametophyte development in Arabidopsis. PLoS One. 8 (6), 66148(2013).

- Wilkinson, L. G., Tucker, M. R. An optimised clearing protocol for the quantitative assessment of sub-epidermal ovule tissues within whole cereal pistils. Plant Methods. 13, 67(2017).

- Hedhly, A., Vogler, H., Eichenberger, C., Grossniklaus, U. Whole-mount clearing and staining of Arabidopsis flower organs and Siliques. Journal of Visualized Experiments. (134), e56441(2018).

- Creff, A., Brocard, L., Ingram, G. A mechanically sensitive cell layer regulates the physical properties of the Arabidopsis seed coat. Nature Communications. 6, 6382(2015).

- Yang, T., et al. The B3 domain-containing transcription factor ZmABI19 coordinates expression of key factors required for maize seed development and grain filling. Plant Cell. 33 (1), 104-128 (2021).

- Anderson, L. E. Hoyer's solution as a rapid permanent mounting medium for bryophytes. Bryologist. 57 (3), 242-244 (1954).

- Herr, J. M. A new clearing-squash technique for the study of ovule development in angiosperms. American Journal of Botany. 58 (8), 785-790 (1971).

- Yadegari, R., et al. Cell differentiation and morphogenesis are uncoupled in Arabidopsis raspberry embryos. The Plant Cell. 6 (12), 1713-1729 (1995).

- Grini, P. E., Jurgens, G., Hulskamp, M. Embryo and endosperm development is disrupted in the female gametophytic capulet mutants of Arabidopsis. Genetics. 162 (4), 1911-1925 (2002).

- Kataoka, K., Uemachi, A., Yazawa, S. Fruit growth and pseudoembryo development affected by uniconazole, an inhibitor of gibberellin biosynthesis, in pat-2 and auxin-Induced parthenocarpic tomato fruits. Scientia Horticulturae. 98 (1), 9-16 (2003).

- de Jong, M., Wolters-Arts, M., Feron, R., Mariani, C., Vriezen, W. H. The Solanum lycopersicum auxin response factor 7 (SlARF7) regulates auxin signaling during tomato fruit set and development. Plant Journal. 57 (1), 160-170 (2009).

- Roth, M., Florez-Rueda, A. M., Paris, M., Stadler, T. Wild tomato endosperm transcriptomes reveal common roles of genomic imprinting in both nuclear and cellular endosperm. Plant Journal. 95 (6), 1084-1101 (2018).

- Orsi, C. H., Tanksley, S. D. Natural variation in an ABC transporter gene associated with seed size evolution in tomato species. PLoS Genetics. 5 (1), 1000347(2009).

- Herridge, R. P., Day, R. C., Baldwin, S., Macknight, R. C. Rapid analysis of seed size in Arabidopsis for mutant and QTL discovery. Plant Methods. 7 (1), 3(2011).

- Xu, T. T., Ren, S. C., Song, X. F., Liu, C. M. CLE19 expressed in the embryo regulates both cotyledon establishment and endosperm development in Arabidopsis. Journal of Experimental Botany. 66 (17), 5217-5227 (2015).

- Ghadiri Alamdari, N., Salmasi, S., Almasi, H. Tomato seed mucilage as a new source of biodegradable film-forming material: effect of glycerol and cellulose nanofibers on the characteristics of resultant films. Food and Bioprocess Technology. 14 (12), 2380-2400 (2021).

- Gardner, R. O. An overview of botanical clearing technique. Stain Technology. 50 (2), 99-105 (1975).

- Beresniewicz, M. M., Taylor, A. G., Goffinet, M. C., Terhune, B. T. Characterization and location of a semipermeable layer in seed coats of leek and onion (Liliaceae), tomato and pepper (Solanaceae). Seed Science and Technology. 23 (1), 123-134 (1995).

- Stebbins, G. L. A bleaching and clearing method for plant tissues. Science. 87 (2245), 21-22 (1938).

- Debenham, E. M. A modified technique for the microscopic examination of the xylem of whole plants or plant organs. Annals of Botany. 3 (2), 369-373 (1939).

- Morley, T. Accelerated clearing of plant leaves by NaOH in association with oxygen. Stain Technology. 43 (6), 315-319 (1968).

Access restricted. Please log in or start a trial to view this content.

Reprints and Permissions

Request permission to reuse the text or figures of this JoVE article

Request PermissionThis article has been published

Video Coming Soon

Copyright © 2025 MyJoVE Corporation. All rights reserved